Abstract

Living in an enriched environment (EE) decreases adiposity, increases energy expenditure, causes resistance to diet induced obesity, and induces brown-like (beige) cells in white fat via activating a hypothalamic-adipocyte axis. Here we report that EE stimulated vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression in a fat depot-specific manner prior to the emergence of beige cells. The VEGF up-regulation was independent of hypoxia but required intact sympathetic tone to the adipose tissue. Targeted adipose overexpression of VEGF reproduced the browning effect of EE. Adipose-specific VEGF knockout or pharmacological VEGF blockade with antibodies abolished the induction of beige cell by EE. Hypothalamic brain-derived neurotrophic factor stimulated by EE regulated the adipose VEGF expression, and VEGF signaling was essential to the hypothalamic brain-derived neurotrophic factor-induced white adipose tissue browning. Furthermore, VEGF signaling was essential to the beige cells induction by exercise, a β3-adrenergic agonist, and a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ ligand, suggesting a common downstream pathway integrating diverse upstream mechanisms. Exploiting this pathway may offer potential therapeutic interventions to obesity and metabolic diseases.

Obesity is controlled by interactions between genetic background, environmental factors, endocrine factors, behavioral factors, and socioeconomic status. The development of obesity is influenced by the balance between two kinds of fat tissues, brown adipose tissue (BAT) dissipating chemical energy as heat on the one hand, with white adipose tissue (WAT) storing excess energy on the other hand. Propensity to obesity in some rodent models correlates with decreased BAT activity, whereas resistance to obesity correlates with increased BAT function or the emergence of brown adipocyte-like cells (beige or brite cells) in WAT (1, 2). Recent research demonstrates that adult humans have metabolically active BAT that can be activated in response to cold temperature, and the presence of BAT correlates inversely with body fat (3–7). This raises the possibility of manipulating BAT to prevent or treat obesity. The induction of beige cells has been observed in a number of gene knockdown or knock-in models (2, 8–10). However, the approaches to induce browning in physiological conditions are limited to chronic cold exposure (11, 12) and more recently voluntary running (13). We have recently published that environmental enrichment (EE), a more complex housing condition that has been shown to influence brain structure and function, leads to antiobesity and anticancer phenotype (14, 15). EE, although a paradigm that provides free access to food, decreases adiposity, increases energy expenditure, causes resistance to diet-induced obesity (DIO), and induces beige cells (16).

EE represents a novel and unique model to study the WAT browning with the following characteristics: 1) intraabdominal WAT is most responsive (16), whereas running induces browning mostly in the sc depot (13); 2) physical activity alone does not account for the EE effects on fat (16); 3) a new brain-fat pathway has been revealed with brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) as a key mediator in the hypothalamus (16); 4) EE provides a model to study social factors in metabolism. There is strong evidence that social and environmental factors can have profound effects on weight and the development of obesity and associated metabolic syndromes (17, 18). However, many studies of the etiology of obesity and metabolic syndromes use genetically modified rodents in laboratory conditions without adequate social interactions. EE can serve as a valuable model to study how the physical and social environments may influence perception, emotion, and other brain circuits and subsequently regulate the whole body physiology (19) and identify potential molecular therapeutic candidates and regulation pathways that might one day be harnessed for the treatment of obesity.

We have teased out one key mechanism by which the social, physical, and cognitive stimuli provided in EE induce BDNF expression in the hypothalamus and thereby activating the hypothalamic-sympathoneural-adipocyte (HSA) axis (14, 16). The preferential sympathoneural activation of WAT leads to the browning of WAT and subsequent energy dissipation. Here we sought to further elucidate the mechanism and identify key mediators in WAT.

Materials and Methods

EE protocol with normal chow diet

We housed male 3-week-old C57BL/6 mice (from Charles River) in large cages (63 cm × 49 cm × 44 cm, five mice per cage) supplemented with running wheels, tunnels, igloos, huts, retreats, wood toys, a maze, and nesting material in addition to standard lab chow and water. We housed control mice under standard laboratory conditions (five mice per cage). All use of animals was approved by, and in accordance with, the Ohio State University Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were housed in temperature- (22°C–23°C) and humidity-controlled rooms with food and water ad libitum. We fed the mice with normal chow diet (11% fat, caloric density 3.4 kcal/g).

rAAV vector construction and packaging

The rAAV plasmid contains a vector expression cassette consisting of the cytomegalovirus enhancer and chicken β-actin promoter, woodchuck posttranscriptional regulatory element, and bovine GH poly-A flanked by AAV inverted terminal repeats. Transgenes [human TrkB isoform 1 (TrkB.T1) cDNA, human BDNF, destabilized yellow fluorescent protein (YFP), human vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-164] were inserted into the multiple cloning sites between the chicken β-actin promoter and woodchuck posttranscriptional regulatory element sequence. rAAV serotype 1 vectors for TrkB.T1, YFP, or BDNF were packaged and purified as described elsewhere (20). Rec2 vectors for VEGF and green fluorescent protein were packaged and purified as described (21).

Sympathetic denervation

We performed unilateral denervation of retroperitoneal fat pad following the reported procedure (22). Forty male C57BL/6 mice, 3 weeks of age, were randomly assigned to receive injection of 6-hydroxydopamine (6OHDA) to one retroperitoneal fat pad, injection five times with 2 μL of 8 mg/mL 6OHDA in 0.01 M PBS plus 1% ascorbic acid (n = 20). Control mice received PBS plus 1% ascorbic acid (n = 20). Four days after the injection, 10 mice receiving the 6OHDA injection and 10 mice receiving the PBS injection were housed in enriched housing (large cage, 1.5 m × 1.5 m × 1.0 m), whereas the rest of mice remained in controlled housing. The experiment was terminated 4 weeks after enrichment housing. We used the norepinephrine ELISA kit (Labor Diagnostika Nord GmbH) to measure norepinephrine in fat lysates. We sonicated the tissues in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-Cl, 1 mM EDTA) for the assay and calibrated to the tissue weight.

Adipose VEGF knockout mice

Dr Andras Nagy (Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Canada) provided mice bearing a Cre recombinase-conditional VEGF allele (VEGFloxP) (23) and mice harboring an adipocyte P2 (aP2)-Cre recombinase transgene (24). We crossed the VEGFloxP with aP2-Cre mice to generate adipose VEGF knockout mice. Genotyping and characterization of the adipose VEGF knockout mice followed Dr. Nagy's protocol (25). Male adipose VEGF knockout mice, 3 weeks of age, were randomly assigned to live in enriched (63 cm × 49 cm × 44 cm, five mice per cage) or control housing for 4 weeks.

AAV serotype 1 (AAV1)-mediated BDNF overexpression in DIO mice

We generated DIO mice by feeding mice with a high-fat diet (HFD) for 10 weeks until the average of body weight reached 40 g. The obese mice were then randomly assigned to receive AAV1-BDNF or AAV1-YFP. Mice were anesthetized with a single dose of ketamine/xylazine (100 mg/kg and 20 mg/kg, ip) and secured via ear bars and incisor bar on a Kopf stereotaxic frame. A midline incision was made through the scalp to reveal the skull and two small holes were drilled into the skull with a dental drill above the injection sites (0.8 mm posterior to the bregma, 0.3 mm lateral to the midline, 5.0 mm dorsal to the bregma). rAAV vectors (1 × 109 genomic particles per site) were injected bilaterally into the hypothalamus the at a rate of 0.1 μL/min using a 10 μL Hamilton syringe attached to Micro4 microsyringe pump controller (World Precision Instruments Inc). At the end of the infusion, the syringe was slowly removed from the brain and the scalp was sutured. Animals were placed back into a clean cage and carefully monitored after surgery until fully recovered from anesthesia. We monitored body weight every 5–7 days and recorded the food intake. Mice were maintained on a HFD until the end of the study (7 wk after surgery).

AAV-mediated overexpression of dominant negative TrkB.T1

We randomly assigned 8-week-old male C57BL/6 mice to receive AAV-TrkB.T1 or AAV-YFP. We injected AAV vectors bilaterally to the hypothalamus (−1.2 AP, ±0.5 ML, −6.2 DV; millimeters from bregma, 5.0 × 109 genomic particles per site). We monitored body weight every 5–7 days and recorded the food intake. We kept the mice on normal chow diet until the end of the study 4 weeks after surgery.

AAV-microRNA experiment

We randomly assigned 7-week-old C57/BL6 mice to receive AAV-microRNA targeting (miR) BDNF (n = 12) or AAV-miR-scrambled (n = 12). We injected AAV vectors (1.4 × 1010 particles per site) bilaterally into the hypothalamus at the stereotaxic coordinates described above. Ten days after surgery, half of the miR-Bdnf mice and miR-scr. mice were housed in EE (large cage, 1.5 m × 1.5 m × 1.0 m), whereas the other half of the groups were maintained in standard housing. After 4 weeks of enriched housing, we dissected fat pads and analyzed the gene expression using quantitative RT-PCR.

Quantitative RT-PCR

We dissected brown and white adipose tissues and hypothalamus and isolated total RNA using an RNeasy lipid kit plus ribonuclease-free deoxyribonuclease treatment (QIAGEN). We generated first-strand cDNA using TaqMan reverse transcription reagent (Applied Biosystems) and carried out quantitative PCR using Light Cycler (Roche) with the Power SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems). Primer sequences are available on request. We calibrated data to endogenous control Actb or Hprt1 and quantified the relative gene expression using the 2-δδCT method (26).

VEGF blockade in EE

We randomly assigned 40 C57BL/6 mice, 3 weeks of age, to live in enriched (20 mice in large cage, 1.5 m × 1.5 m × 1.0 m) or control cages. Half of each housing group was injected with a monoclonal antibody B20–4.1 that blocks VEGF interaction with both VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 (kindly provided by Genentech). The other half of each housing group was injected with isotype control IgG (Sigma). The antibody injection began just before the initiation of EE and continued for 4 weeks (0.1 mg/mouse, ip once per week). Fat pads were dissected and analyzed after 4 weeks of EE. Similar experiment was performed using a monoclonal antibody r84 that selectively blocks VEGF from interacting with VEGFR2 (gift from Dr Rolf Brekken, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas; 0.1 mg per mouse, twice per week).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. We used JMP software (SAS) to analyze the following: Student's t test for comparison between two groups; one-way ANOVA with a post hoc test for comparisons between multiple groups; regression for adipose tissue weight-gene expression correlation.

Extended methods can be found in the Supplemental Information online.

Results

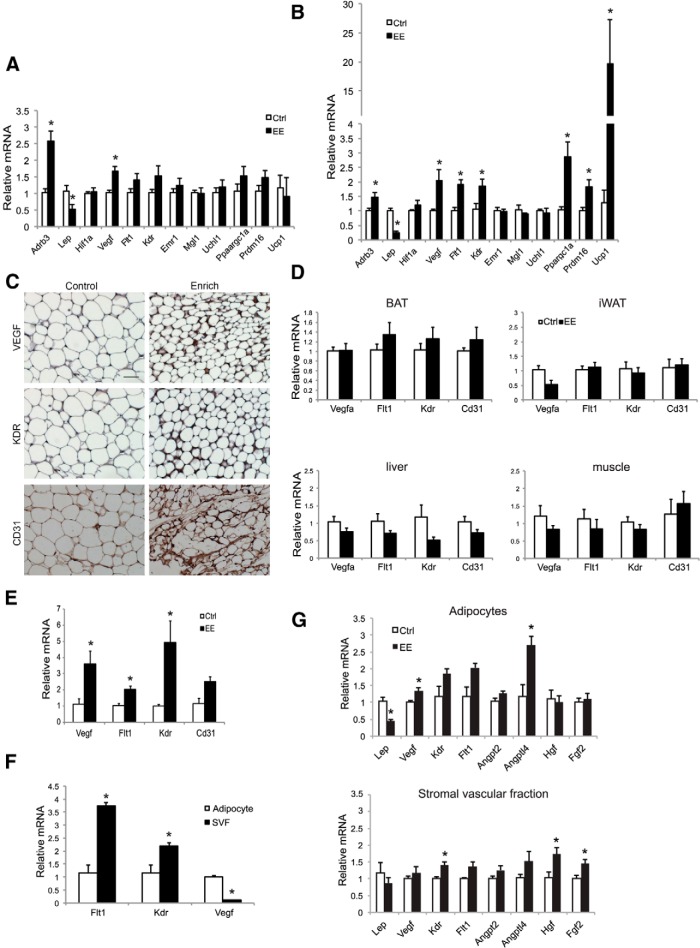

EE induces VEGF expression and angiogenesis

To examine additional consequences of HSA axis activation, we examined changes in the retroperitoneal WAT (rWAT) (27) brought by short-term EE of 6 days. Quantitative RT-PCR was used to measure markers of angiogenesis (Vegf, Hif1a), macrophages (Emr1 encoding F4/80, MglI), peripheral nerve (Uchl1 encoding PGP95) (28), all previously implicated in adipose remodeling (29), brown adipocyte markers (Prdm16, Ucp1, Ppargc1a), β3-adrenergic receptor (β3-AR), and leptin (Figure 1A). Short-term EE increased β3-AR expression and decreased leptin expression. Interestingly, Vegf expression was up-regulated significantly, whereas no changes in macrophage markers or peripheral nerve markers were observed (Figure 1A). No induction of the brown gene program was observed at the 6-day time point (Figure 1A). With progression of EE by the 4-week time point, Vegf up-regulation was sustained, whereas both VEGF receptors (Flt1 encoding VEGF receptor 1 and Kdr encoding VEGF receptor 2) showed increased gene expression (Figure 1B). Immunohistochemistry showed increased VEGF and its receptor kinase insert domain receptor (KDR) as well as the vascular marker CD31 in rWAT of EE mice (Figure 1C). Consistent with published data (16), 4 weeks of EE led to the strong induction of the brown gene program in rWAT (Figure 1B). Macrophage and peripheral nerve markers remained unchanged (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

EE up-regulates VEGF expression and enhances angiogenesis in rWAT. A, rWAT gene expression profile after 6 days of EE (n = 5 per group). *, P < .05. B, rWAT gene expression profile after 4 weeks of EE (n = 5 per group). *, P < .05. C, Immunohistochemistry of rWAT after 4 weeks of EE. Scale bar, 50 μm. D, VEGF and vascular markers expression in BAT, iWAT, liver, and muscle after 4 weeks of EE (n = 5 per group). E, rWAT gene expression profile after 3 months of EE (n = 4 per group). *, P < .05. F, Relative mRNA levels of Vegf and its receptors in rWAT of control mice. G, Gene expression changes in rWAT adipocyte and SVF after 6 days of EE (n = 5 per group). *, P < .05. Ctrl, control housing.

These data suggest that VEGF up-regulation is among the earliest molecular events triggered in rWAT by EE. Other members of the VEGF family, specifically VEGF-B and placental growth factor, showed no change. We then measured VEGF expression in inguinal WAT (iWAT) after 4 weeks of EE. As reported previously, iWAT was less responsive to EE with no changes of peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1 (PGC-1)-α, Prdm16, or uncoupling protein-1 (UCP1) in iWAT (16). Interestingly, no Vegf or Cd31 up-regulation was observed in iWAT by 4 weeks of EE (Figure 1D), coincident with the lack of brown gene program induction in iWAT (16). However, leptin expression was decreased by approximately 77%, suggesting the dissociation of leptin suppression from the browning effect of EE. VEGF plays a direct role in the maintenance, activation, and expansion of BAT (30, 31). However, the expression of Vegf and its receptors were not changed in BAT, liver, or skeletal muscle with 4 weeks of EE (Figure 1D). These data suggest an organ-specific, and even an adipose depot-specific, regulation of VEGF and angiogenesis by EE. However, the EE-induced depot-preferential browning was not associated with the norepinephrine (NE) level in different fat depots. EE increased the NE level by 35.6% ± 15.9% in iWAT, 99.5% ± 24.8% in epididymal WAT, and 76.3% ± 12.3% in rWAT. Contrary to the transient up-regulation of VEGF by cold exposure (32), EE led to the sustained up-regulation of VEGF and its receptors for at least 3 months (Figure 1E).

To investigate the source of the VEGF up-regulation in adipose tissue, we isolated adipocytes and stromal vascular fractions (SVF) of the rWAT after 6 days of EE. Vegf was mainly expressed in the adipocyte, whereas its receptors were expressed at a higher level in the SVF in control mice (Figure 1F). Vegf up-regulation was observed in the adipocytes but not in the SVFs (Figure 1G). In contrast, Kdr was up-regulated only in the SVFs (Figure 1G). We screened additional proangiogenic factors. Hgf (encoding hepatocyte growth factor) and Fgf2 (encoding fibroblast growth factor 2) were up-regulated only in the SVFs. No change in Angpt2 (encoding angiopoietin 2) was found (Figure 1G).

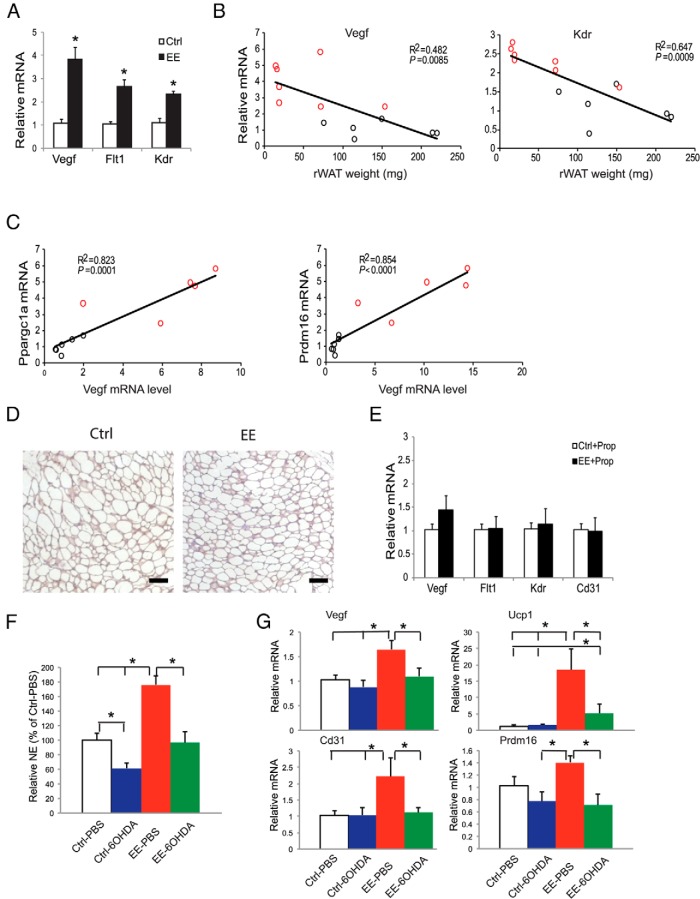

Our previous experiments showed that EE inhibited DIO. Four weeks of EE significantly decreased adiposity, improved the metabolic profile, and induced a robust brown gene program in rWAT (16). We measured Vegf expression in DIO mice and found that EE increased the expression of Vegf and its receptors to a greater extent than that observed in mice fed a normal diet (Figures 1B and 2A). Furthermore, mRNA levels of Vegf and Kdr were inversely correlated with the rWAT mass (Figure 2B), consistent with a robust functional effect of these molecular changes. Notably, brown adipocyte markers Ppargc1a and Prdm16 were also inversely correlated with rWAT mass (16). Moreover, both Ppargc1a and Prdm16 were positively correlated with Vegf (Figure 2C) and Kdr (Ppargc1a-Kdr: R2 = 0.621, P = .004; Prdm16-Kdr: R2 = 0.637, P = .003).

Figure 2.

EE induces VEGF expression in DIO mice (A–C). A, rWAT gene expression after 4 weeks of EE and HFD feeding (n = 5 per group). *, P < .05. B, Correlation of Vegf and Kdr mRNA levels to rWAT weight after 4 weeks of EE and HFD feeding. C, Correlation of Ppargc1a and Prdm16 mRNA level to Vegf level. Red circles, individual EE mouse; black circles, individual control mouse. D, Representative hypoxyprobe staining in rWAT after 6 days of EE. Scale bar, 50 μm. E, rWAT gene expression profile after 4 weeks of EE and oral propranolol treatment (n = 5 per group). F, rWAT NE level in 6OHDA denervation mice after 4 weeks of EE (n = 5 per group). *, P < .05 between groups as indicated. G, rWAT gene expression profile in 6OHDA denervation mice after 4 weeks of EE (n = 5 per group). *, P < .05 between groups as indicated. Ctrl, control housing.

Angiogenesis is commonly initiated by tissue hypoxia. To determine whether WAT hypoxia was involved in the EE-induced VEGF up-regulation, mice were housed in control or EE housing for 6 days. The presence of adipose tissue hypoxia was examined by hypoxyprobe staining (33). rWATs of the EE mice showed less hypoxic areas compared with the control mice (Figure 2D), suggesting the EE-induced VEGF up-regulation was hypoxia independent.

The EE-induced WAT browning requires an intact sympathetic nervous system (SNS), and the brown gene program could be blocked by oral administration of β-blocker propranolol (16). To determine the role of SNS in EE-induced angiogenesis, mice were housed in control and EE housing with propranolol supplied in the drinking water (0.5 g/L) immediately when EE was initiated. Propranolol completely blocked the induction of Vegf and vascular markers by EE (Figure 2E), suggesting the modulation of angiogenesis was downstream of SNS tone to rWAT in EE. Moreover, we performed unilateral sympathetic denervation of the rWAT by local injection of 6OHDA (22). The mice receiving 6OHDA or vehicle were then split to live in EE or control housing for 4 weeks. 6OHDA denervation led to approximately 40% decrease of NE in rWAT and prevented the increase of NE associated with EE (Figure 2F). Partial sympathetic denervation blocked the up-regulation of Vegf, increased angiogenesis, and induced the brown gene program induced by EE in the 6OHDA-injected rWAT (Figure 2G). Unilateral denervation of rWAT did not block the up-regulation of hypothalamic Bdnf expression or the decrease of adiposity induced by EE (Supplemental Figure 1).

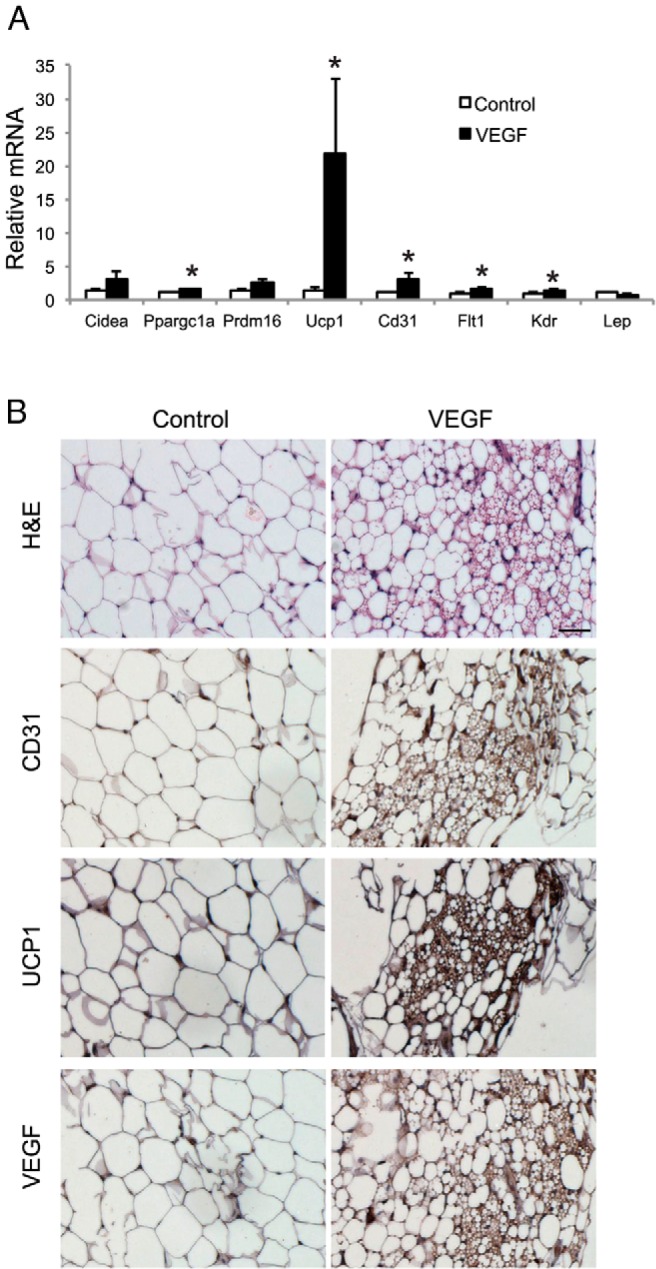

Overexpression of VEGF in rWAT reproduces the browning effect of EE

To perform a gain-of-function study of the role of VEGF in browning of WAT, we generated a recently engineered serotype of AAV vector, Rec2, that could sufficiently deliver transgene to adipose tissues (21). We injected Rec2 vector harboring human VEGF directly to the rWAT. AAV-mediated VEGF overexpression led to 4.53- ± 0.98-fold increase of VEGF level in rWAT. Four weeks after AAV injection, brown markers Ucp1 and Ppargc1a were significantly induced in rWAT receiving VEGF vector compared with rWAT receiving an empty viral vector as control (Figure 3, A and B). Beige cells were observed in rWAT receiving VEGF vector adjacent to the areas of increased vasculature (Figure 3B), indicating that overexpressing VEGF in rWAT could reproduce the browning effect of EE. However, VEGF overexpression did not significantly suppress leptin expression (Figure 3A), a molecular feature induced by EE, suggesting VEGF signaling was specifically involved in the browning effect of EE but may not be involved in the regulation of leptin expression.

Figure 3.

rAAV-mediated overexpression of VEGF in rWAT. A, rWAT gene expression profile 4 weeks after Rec2-VEGF injection (n = 8 per group). *, P < .05. B, Immunohistochemistry of rWAT. Scale bar, 50 μm.

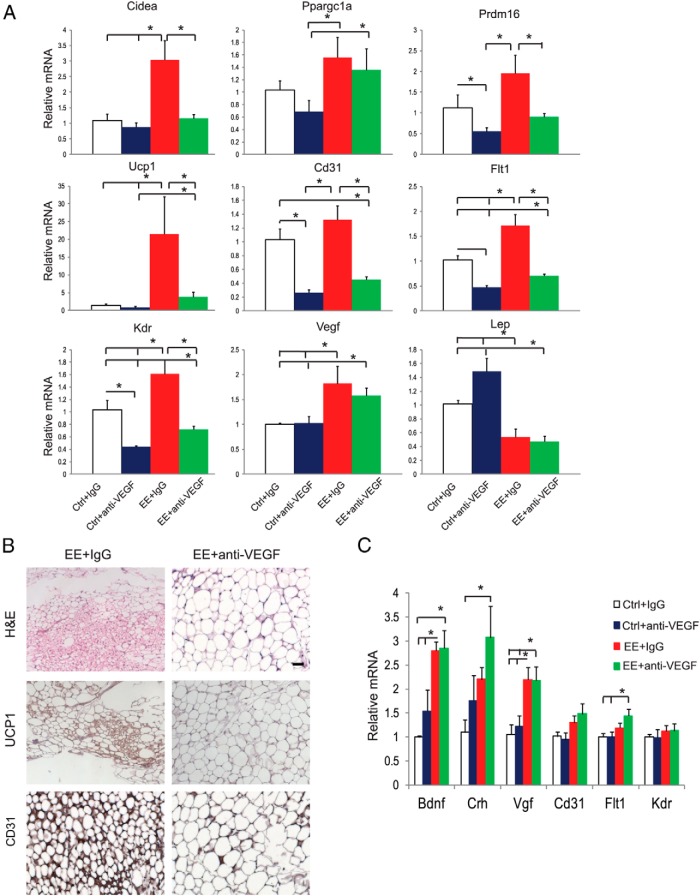

VEGF blockade blocks EE-induced WAT browning

To investigate whether VEGF signaling was essential for EE-induced browning, the anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody B20–4.1 was used to antagonize VEGF interaction with VEGF receptor 1 and receptor 2 (34, 35). Mice were randomized to live in control and EE housing. Half of each housing group was injected with B20–4.1 (0.1 mg per mouse, ip), and the other half of each housing group was injected with isotype control IgGs (0.1 mg per mouse) once per week. The antibody injection began just before the initiation of EE and continued for 4 weeks. In control housing, anti-VEGF antibody resulted in slight change in adiposity (Supplemental Figure 2A). In EE housing, robust reduction of adiposity was observed in control IgG-treated mice. Anti-VEGF antibody did not attenuate the decrease of rWAT mass associated with EE (Supplemental Figure 2A). At the molecular level, anti-VEGF antibody markedly decreased the expression of vascular markers Cd31, Flt1, and Kdr in both control and EE housing, confirming the robust antiangiogenic effect of the antibody (Figure 4A, B). The anti-VEGF antibody blocked most brown gene program induced by EE including Ucp1 (Figure 4A, B). Immunohistochemistry confirmed the blockade of EE-induced browning (Figure 4B). Anti-VEGF antibody showed no effects on the expression of VEGF or leptin (Figure 4A). However, the EE-induced increase of adiponectin and decrease of resistin expression were blocked by anti-VEGF antibody (Supplemental Figure 2B).

Figure 4.

Anti-VEGF antibody blocks rWAT browning induced by EE. A, Gene expression profile of rWAT after 4 weeks of EE and anti-VEGF antibody treatment (n = 5 per group). *, P < .05 between groups as indicated. B, Immunohistochemistry of rWAT. Scale bar, 50 μm. C, Gene expression profile of hypothalamus (n = 5 per group). *, P < .05 between groups as indicated. Ctrl, control housing.

To investigate whether the anti-VEGF antibody interfered with the signature gene expression profile in response to EE, we examined the hypothalamic expression of several genes associated with EE. Bdnf, Crh (encoding corticotrophin-releasing hormone), and Vgf (encoding nerve growth factor inducible) were all up-regulated by EE in control IgG-treated mice (Figure 4C), consistent with our published data (16). The anti-VEGF antibody did not block these changes in the hypothalamus (Figure 4C). In addition, anti-VEGF antibody showed no antiangiogenic effect in the hypothalamus (Figure 4C). The effects of anti-VEGF antibody on BAT were shown in Supplemental Figure 2C. Furthermore, we performed a similar experiment using a monoclonal antibody r84 (Mcr84) that binds VEGF and selectively blocks VEGF from interacting with KDR (36). Scherer and colleagues (33) used Mcr84 in a DIO model and observed an impaired response to the HFD in Mcr84-treated mice, although food intake, weight gain, and fat pad size did not differ. Mcr84-treated mice showed decreased CD31 level in iWAT but not in liver, indicating that antiangiogenesis treatment primarily affects fat. Our data showed that r84 significantly attenuated the brown gene program induced by EE (Supplemental Figure 3), suggesting KDR signaling was important for the angiogenic and browning effects of EE.

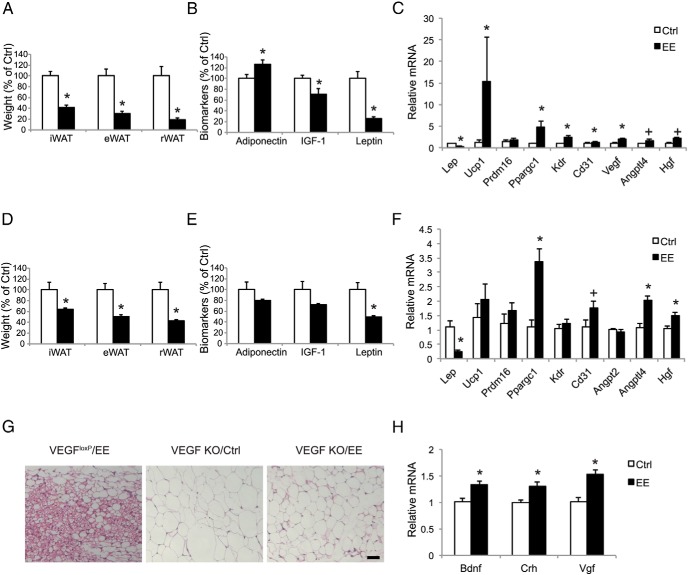

EE fails to induce browning in adipose VEGF knockout mice

We generated adipose-specific VEGF knockout mice by crossing mice bearing a Cre recombinase-conditional VEGF allele (VEGFloxP) (23), with the mice carrying an aP2-Cre recombinase transgene (24). The adipose-specific VEGF knockout mice have been well characterized, showing trace amount of VEGF in the adipose tissue and reduced vascular density (25). Quantitative RT-PCR and ELISA showed that the genetic ablation of VEGF by aP2-Cre significantly decreased VEGF transcript and protein levels by 53.1% ± 6.5% and 72.4% ± 8.9%, respectively, in rWAT, whereas no changes in liver or muscle were found. VEGFloxP mice responded to EE similarly to wild-type mice, with a robust decrease in adiposity (Figure 5A), changes in serum markers (Figure 5B), and induction of a gene program characterized as suppression of leptin, up-regulation of Vegf and Cd31, and induction of brown gene expression (Figure 5C). Beige cells were found in the rWAT of VEGFloxP mice after 4 week of EE (Figure 5E). In contrast, the emergence of beige cells was not observed in adipose VEGF knockout mice after EE, although the adipocytes appeared smaller compared with the mice living in control housing (Figure 5G). The adipose VEGF knockout mice showed less decrease in adiposity (Figure 5D) and changes in serum biomarkers (Figure 5E) in response to EE compared with the VEGFloxP mice (Figure 5, A and B). EE failed to induce brown adipocyte marker Ucp1 in adipose VEGF knockout mice (Figure 5F). In contrast, leptin expression was robustly suppressed consistent with the finding in pharmacological VEGF blockade (Figures 4A and 5F) supporting the notion that the leptin suppression and browning are dissociated. Interestingly, the vascular marker Cd31 showed a trend of up-regulation in EE adipose VEGF knockout mice (Figure 5F), probably due to the induction of other proangiogenic factors such as Angptl4 and Hgf (Figure 5F). Adipose VEGF ablation did not inhibit the hypothalamic molecular features in response to EE. Bdnf, Crh, and Vgf were all up-regulated by EE (Figure 5H).

Figure 5.

Adipose VEGF knockout mice show no EE-induced browning. A, Fat pad mass of VEGFloxP mice after 4 weeks of EE (n = 5 per group). *, P < .05. B, Serum biomarkers of VEGFloxP mice after 4 weeks of EE (n = 5 per group). *, P < .05. C, rWAT gene expression profile of VEGFloxP mice after 4 weeks of EE (n = 5 per group), *, P < .05, + P = .06. D, Fat pad mass of adipose VEGF knockout mice after 4 weeks of EE (n = 7 control housing; n = 9 EE housing). *, P < .05. E, Serum biomarkers of adipose VEGF knockout mice after 4 weeks of EE (n = 7 control housing; n = 9 EE housing). *, P < .05. F, rWAT gene expression profile of adipose VEGF knockout mice (n = 7 control housing; n = 9 of EE housing). *, P < .05, + P = .06. G, H&E of rWAT. Scale bar, 50 μm. H, Gene expression profile of hypothalamus of adipose VEGF knockout mice after 4 weeks of EE (n = 5 per group). *, P < .05. Ctrl, control housing; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

Antivascular endothelial-cadherin (VE-cad) treatment does not block EE-induced browning

To investigate whether the effect of VEGF was dependent on angiogenesis, we used an antibody targeting VE-cad, an endothelial cell-specific adhesion molecule. The monoclonal antibody BV13 directing to the extracellular region of VE-cad has been characterized as a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis in vivo (27, 37). Mice were randomized to live in control and EE housing. Half of each housing group was injected with anti-VE-cad BV13 (0.05 mg per mouse, ip), the other half of each housing group was injected with isotype control IgGs (0.05 mg per mouse) twice per week. Anti-VE-cad treatment sufficiently blocked the increase of vascular marker Cd31 in response to EE (Supplemental Figure 4) but showed no impact on brown genes program or Vegf up-regulation (Supplemental Figure 4).

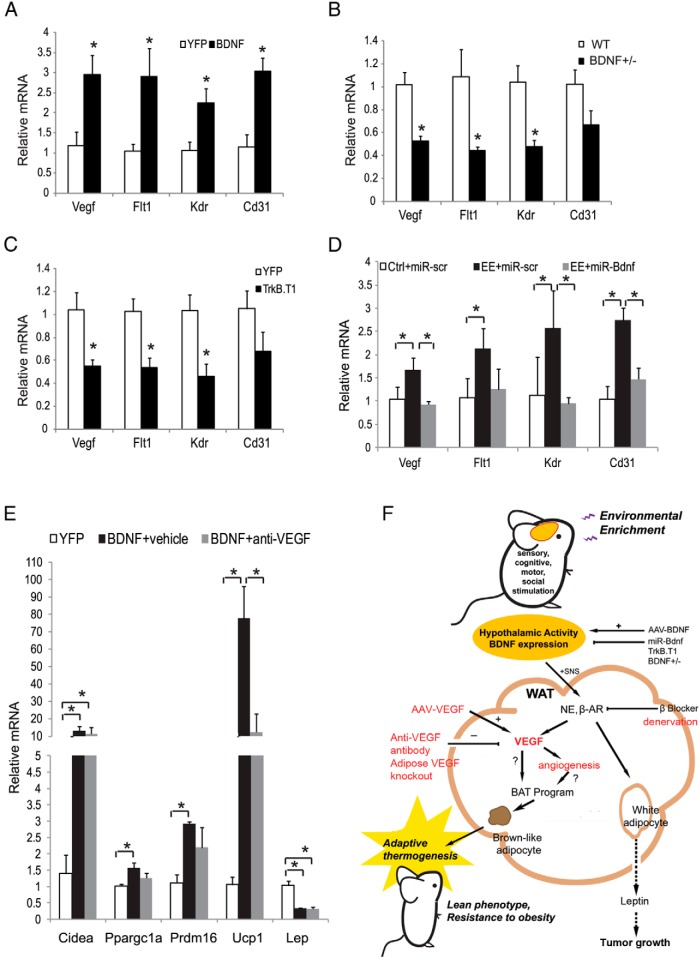

Hypothalamic BDNF regulates WAT VEGF signaling

BDNF has been identified as a key mediator of EE-induced WAT browning (16). Here we investigated the role of hypothalamic BDNF in the regulation of VEGF signaling and angiogenesis in WAT. rAAV-mediated overexpression of BDNF in the hypothalamus increased the expression of Vegf, its receptors, and Cd31 in rWAT (Figure 6A). BDNF heterozygous mice with hypothalamic BDNF protein levels approximately 40% lower than wild type develop adult-onset obesity (38). We have published that BDNF+/− mice show a substantial increase in the fat pad mass before significant body weight difference occurs (16). The molecular features of rWAT in BDNF+/− mice were a complete reversal of that found with EE or BDNF-overexpressing mice, namely a suppression of β-ARs and brown gene program. Our new data show that Vegf and its receptor expression were decreased in rWAT of BDNF+/− mice (Figure 6B). In contrast, altered expression of Flt1 and Kdr was not observed in muscles, suggesting a selective modulation of angiogenesis in adipose tissue by BDNF. In addition to the global inhibition of BDNF in BDNF+/− mice, we have developed two strategies to inhibit hypothalamic BDNF: one is a dominant-negative truncated form of the high-affinity BDNF receptor (TrkB.T1) (39), and the other is a microRNA targeting BDNF (miR-Bdnf) (14, 16). The injection of AAV-TrkB.T1 to the hypothalamus led to molecular features in rWAT similar to those found in the BDNF+/− mice. Similarly, AAV-miR-Bdnf knocked down BDNF expression and completely blocked the EE-induced brown gene program in rWAT (16). AAV-TrkB.T1 led to a substantial decrease of the expression of Vegf and its receptors in rWAT (Figure 6C). AAV-miR-Bdnf completely blocked the increase of Vegf and vascular markers induced by EE, whereas the control vector targeting a scrambled sequence (AAV-miR-scr) showed no effect (Figure 6D). Next, we investigated whether anti-VEGF antibody could attenuate the browning effect induced by hypothalamic overexpressing BDNF. Mice injected with AAV-BDNF to the hypothalamus were randomly assigned to receive anti-VEGF antibody B20–4.1 or vehicle twice weekly. Antibody injection began 2 days after AAV injection and continued for 4 weeks. Consistent with our previous findings (16), hypothalamic BDNF overexpression led to robust induction of the brown gene program in rWAT, notably a 77-fold increase in Ucp1 expression. Anti-VEGF antibody substantially attenuated the increase of Ucp1 expression by 85% (Figure 6E) and the elevated energy expenditure measured by indirect calorimetry (Supplemental Figure 5).

Figure 6.

BDNF regulates adipose tissue VEGF. A, Gene expression of rWAT in HFD mice overexpressing BDNF in the hypothalamus (n = 5 per group). *, P < .05. B, Gene expression of rWAT in BDNF+/− mice (n = 4 per group). * P < .05. C, Gene expression of rWAT in AAV-TrkB.T1 injected mice (n = 4 per group). *, P < .05. D, Gene expression of rWAT in mice after hypothalamic injection of rAAV-microRNA targeting BDNF and lived in EE for 4 weeks (n = 5 per group). *, P < .05 between groups as indicated. E, rWAT gene expression in mice after hypothalamic injection of rAAV-BDNF and treated with anti-VEGF antibody (n = 5 per group). *, P < .05 between groups as indicated. F, Mechanism of EE-induced WAT browning. Environmental stimuli provided by EE stimulate hypothalamic BDNF expression, leading to the activation of the HSA axis. The preferential increase of SNS tone to the WAT suppresses leptin expression, resulting in anticancer effects. Activating the HSA axis up-regulates adipose VEGF expression, leading to the induction of brown-like adipocyte in WAT. Overexpression of VEGF directly in the rWAT reproduces the browning effect of EE. The blockade of VEGF signaling attenuates the browning effect of EE. Ctrl, control housing.

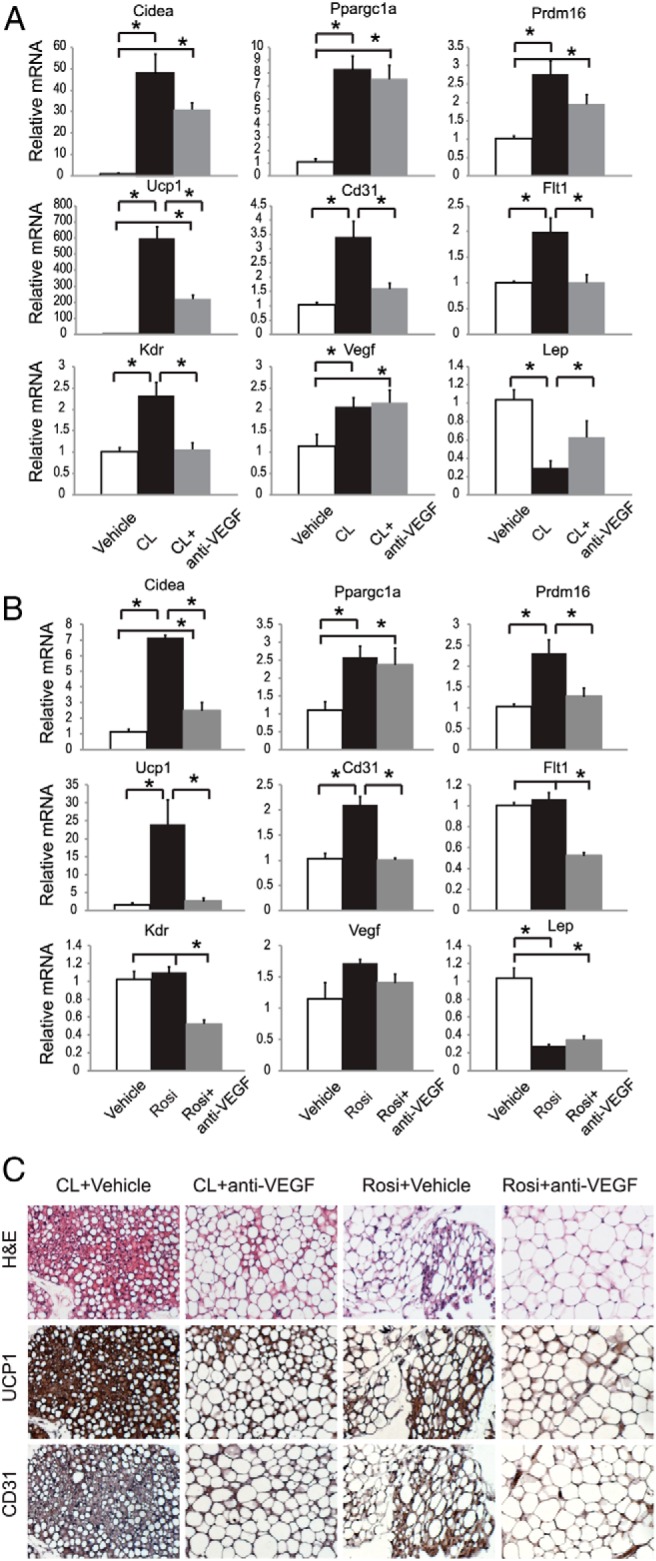

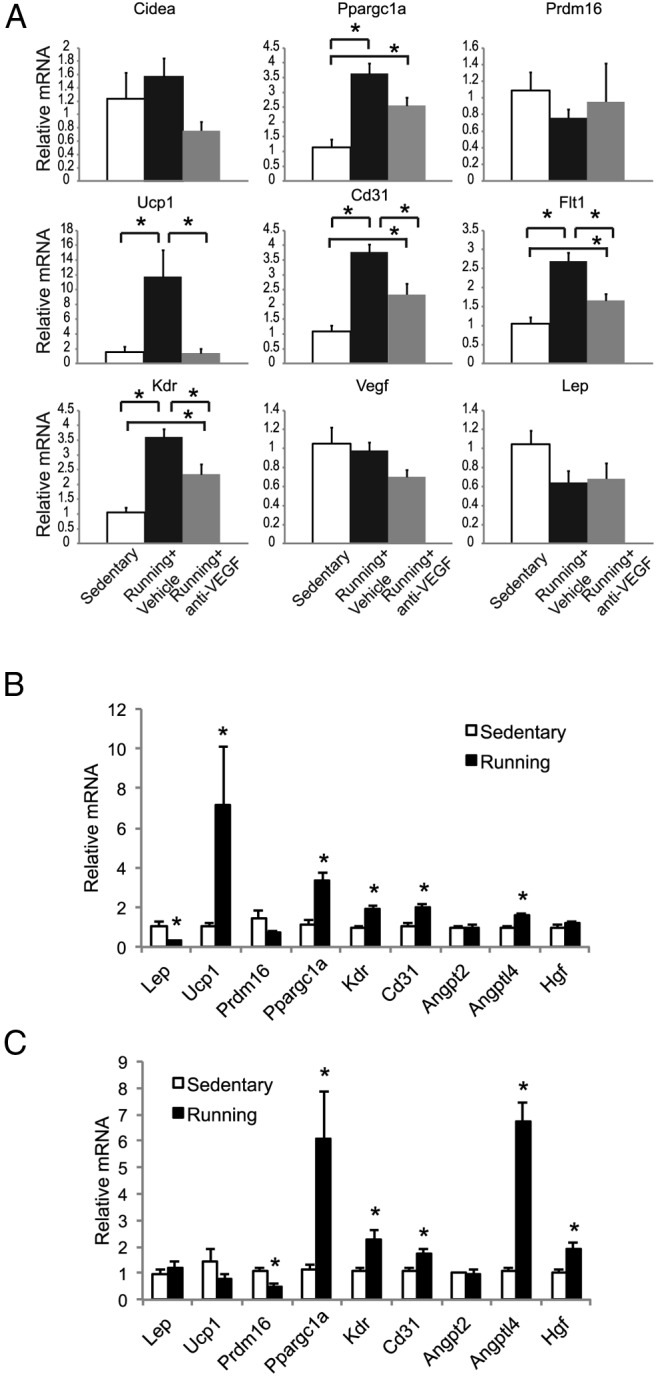

VEGF signaling is required for browning induced by diverse physiological and pharmacological approaches

To determine whether VEGF played a role in the induction of beige cells by other approaches in addition to EE, we investigated the effects of anti-VEGF antibody in three additional models, including chronic administration of the β3-agonist CL-316243 and the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ ligand rosiglitazone as well as voluntary running. Chronic treatment with CL-316243 can mimic the stimulating effects of cold exposure with massive induction of beige cells (40). Mice were randomized to receive vehicle, CL-316243 (1 mg/kg, ip, daily), or CL-316243 plus anti-VEGF antibody B20–4.1. The antibody (0.1 mg/mouse, ip) was injected every 3 days. Nine days of CL-316243 administration led to a significant induction of Vegf, Flt1, Kdr, and Cd31 expression coincident with a massive induction of the brown gene program in rWAT (Figure 7, A and C). The anti-VEGF antibody completely blocked the angiogenic effect of CL-316243 and significantly attenuated the Ucp1 up-regulation by 66% (Figure 7, A and C). The occurrence of beige cells brought by CL-316243 was markedly diminished by VEGF blockade (Figure 7C). Anti-VEGF antibody also blocked the browning of iWAT in CL-316243-treated mice (Supplemental Figure 6).

Figure 7.

Effects of VEGF blockade in mice treated with β-adrenergic agonist or PPAR-γ ligand. A, rWAT gene expression profile after chronic injection of CL316,243 and anti-VEGF antibody (n = 5 per group). *, P < .05 between groups as indicated. B, rWAT gene expression profile after chronic injection of rosiglitazone and anti-VEGF antibody (n = 5 per group). *, P < .05 between groups as indicated. C, Immunohistochemistry of rWAT. Scale bar, 50 μm. CL, CL316,243; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

Activation of PPAR-γ by synthetic ligands induces beige cells in WAT (41, 42) through mechanisms yet to be completely understood. One of the mechanisms may involve the stabilization of PR domain containing 16 (PRDM16) protein (43). Chronic treatment of rosiglitazone (10 mg/kg, ip, daily) for 9 days resulted in significant up-regulation of Cd31, whereas Vegf, Flt1, and Kdr were not changed (Figure 7, B and C). However, anti-VEGF antibody completely abolished the increase of Cd31 as well as the induction of Prdm16 and Ucp1 by rosiglitazone in rWAT (Figure 7, B and C).

Exercise induces beige cells in WAT mediated by the myokine irisin (13). Mice housed in a larger space with access to running wheels for 3 weeks showed a marked increase of vascular markers Cd31, Flt1, and Kdr, although no change of Vegf was found (Figure 8A). Wheel running increased Ppargc1a and Ucp1 expression (Figure 8A). Pharmacological VEGF blockade (weekly injection of B20–4.1) could partially block the increase of vascular markers while completely abolishing the induction of Ucp1 in rWAT (Figure 8A). Anti-VEGF antibody also sufficiently antagonized the induction of Ucp1 in iWAT (Figure S7). Furthermore, wheel running failed to induce WAT browning in the adipose VEGF knockout mice (Figure 8C), whereas control mice (VEGFloxP and aP2-Cre) showed significant induction of Ucp1 (Figure 8B). Interestingly, running-induced up-regulation of Cd31 was not blocked in adipose VEGF knockout mice (Figure 8C). Moreover, proangiogenic factor Hgf showed stronger up-regulation in the adipose VEGF knockout mice compared with control mice (Figure 8, B and C), suggesting additional angiogenic signals may mediate the exercise-induced angiogenesis in rWAT. In contrast, the induction of Ucp1 was particularly sensitive to VEGF signaling.

Figure 8.

Effects of VEGF blockade in mice subjected to voluntary wheel running. A, rWAT gene expression profile of wild-type mice after 3 weeks of wheel running and anti-VEGF antibody treatment (n = 5 per group). *, P < .05 between groups as indicated. B, rWAT gene expression profile of control mice (VEGFloxP and aP2-Cre) after 3 weeks of wheel running (n = 5–7 per group). *, P < .05. C, rWAT gene expression profile of adipose VEGF knockout mice after 3 weeks of wheel running (n = 4 per group). *, P < .05.

Discussion

Our results identify adipose VEGF as a key component of the HSA axis underlying the browning effect of a rich physical and social environment (Figure 6F). VEGF is the only bona fide endothelial cell growth factor, and its presence is essential for initiation of the angiogenic program (44, 45). VEGF levels can be regulated by hypoxia, insulin stimulation, certain growth factors, and cytokines (46, 47). Our data show that the Vegf up-regulation occurred prior to the induction of PGC-1α and Ucp1, suggesting that Vegf up-regulation is an immediate early event that contributes to the emergence of beige cells. What might mediate the VEGF up-regulation? Hypoxia is not involved because hypoxyprobe staining showed less hypoxic areas in rWAT of EE mice and Hif1a was not changed. Leptin has a proangiogenic property (48), but leptin is sharply decreased in EE. PGC-1α has been shown to directly activate VEGF expression at the transcriptional level via a HIF-independent pathway (49). However, EE-induced Vegf up-regulation is likely to be the cause of PGC-1α induction rather than the consequence because the Vegf up-regulation occurred prior to the increase of PGC-1α. It is most likely that the sympathetic stimulation of WAT directly causes the Vegf up-regulation. The systemic β-AR blockade experiment and local sympathetic denervation study indicate that sympathoneural activity is required for the adipose Vegf up-regulation and browning.

Targeted overexpression of VEGF in rWAT by a novel rAAV serotype reproduced the angiogenic and browning effects of EE consistent with recent reports on transgenic mice with adipose-specific overexpressing of VEGF (25, 33). However, loss-of-function studies to investigate the role of VEGF in beige cell induction under physiological conditions have not been reported. Our results show that anti-VEGF antibody treatment blocked the brown gene program and the emergence of beige cells induced by EE. The data of adipose specific VEGF knockout mice further support the essential role of VEGF in WAT browning. The identity of precursor cells responding to VEGF is of great interest and requires further investigation. Lineage tracing studies indicate that the vascular wall of adipose tissue capillaries represents the niche of adipocytes precursors (50). Moreover, recent data demonstrate that adipocytes in both white and brown fat depots originate from cells that display endothelial characteristics, supporting the notion that adipogenesis and angiogenesis are coordinated during adipose tissue expansion (51).

VEGF is important for BAT development and maintenance (31, 52). Sung et al (25) studied two gene-targeted mouse lines with lacZ knocked into the loci for either Flt1 (53) or Kdr (54) and found that the VEGF receptors were expressed by endothelial cells but not by white or brown adipocytes and concluded that the effect of VEGF on adipose function is mediated through blood vessels. However, these data cannot rule out that VEGF receptors are expressed by adipose precursor cells with endothelial origin. Indeed, functional classical brown adipocytes can be produced from human pluripotent stem cells using a specific hemopoietin cocktail composed of KIT ligand, fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand, IL-6, bone morphogenetic protein-7, and VEGF. VEGF was required for PRDM16 expression, whereas KIT ligand, IL-6, or fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand was required for subsequent UCP1 expression (55). In our study, VEGF was the only component of this cocktail that responded to EE. Several lines of evidence suggest VEGF may have actions independent of angiogenesis. In the adipose specific VEGF knockout mice, adipose angiogenesis was increased by EE, whereas induction of beige cells were completely blocked. Moreover, the non-VEGF antiangiogenic agent anti-VE-cad antibody sufficiently abolished the increase of angiogenesis but did not inhibit EE-induced browning. These data suggest other proangiogenic factors (for example, Angptl4, Hgf) may contribute to the EE-induced adipose angiogenesis, whereas VEGF may act on adipose precursor cells in addition to its proangiogenic functions.

Progress has been made in elucidating the cell-surface phenotype, functional markers, and molecular signatures of fat depot-specific preadipocytes. For example, PDGFRα+ cells have been identified as bipotential adipocyte progenitors that can be recruited by β3-AR activation and HFD (56). Zfp423, a gene controlling preadipocytes determination, was found in a small subset of capillary endothelial cells within WAT and BAT, suggesting a contribution of specialized endothelial cells to the adipose lineage (57). EE is a model providing physiological signals that potentially determine adipocytes and/or endothelial cell fates. Coupling EE with the platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α reporter mice (56) and/or the Zfp423-green fluorescent protein mice (57) can lead to a better understanding of the mechanisms responsible for adipose remodeling in response to environmental stimuli.

One of the key findings of this study is that VEGF integrates multiple upstream stimulations to a common pathway that is essential to the emergence of beige cells. In addition to EE, VEGF blockade could substantially block the browning induced by the β3-adrenergic agonist CL-316243, the PPARγ ligand rosiglitazone, and voluntary running. UCP1 was particularly sensitive to the anti-VEGF antibody whose up-regulation by EE, running, or rosiglitazone was completely abolished. Thus, VEGF signaling is likely a downstream pathway shared by diverse physiological and pharmacological stimuli that all lead to the induction of beige cells, suggesting coordination between angiogenesis and the white-to-brown switch. Targeting this common pathway may have therapeutic potential.

Acknowledgments

We thank Genentech for the gift of the B20–4.1 antibody, Dr Rolf Brekken (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center) for the r84 antibody, Dr Andras Nagy (Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Canada) for providing the VEGFloxP mice and aP2-Cre mice, and Dr F. Lee (Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, New York) for providing the BDNF+/− mice.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants CA166590 and CA163640 and The Comprehensive Cancer Center fund (to L.C.) and by National Institutes of Health Grant NS44576 (to M.J.D.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AAV1

- AAV serotype 1

- aP2

- adipocyte P2

- β3-AR

- β3-adrenergic receptor

- BAT

- brown adipose tissue

- BDNF

- brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- DIO

- diet-induced obesity

- EE

- environmental enrichment

- HFD

- high-fat diet

- HSA

- hypothalamic-sympathoneural-adipocyte

- iWAT

- inguinal WAT

- KDR

- kinase insert domain receptor

- miR

- microRNA targeting

- NE

- norepinephrine

- 6OHDA

- 6-hydroxydopamine

- PGC-1

- PPAR-γ coactivator 1

- PPAR

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- PRDM16

- PR domain containing 16

- rWAT

- retroperitoneal WAT

- SNS

- sympathetic nervous system

- SVF

- stromal vascular fractions

- UCP1

- uncoupling protein-1

- VE-cad

- vascular endothelial-cadherin

- VEGF

- vascular endothelial growth factor

- WAT

- white adipose tissue

- YFP

- yellow fluorescent protein.

References

- 1. Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:277–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Seale P, Conroe HM, Estall J, et al. Prdm16 determines the thermogenic program of subcutaneous white adipose tissue in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:96–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nedergaard J, Bengtsson T, Cannon B. Unexpected evidence for active brown adipose tissue in adult humans. Am J Physiol. 2007;293:E444–E452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Saito M, Okamatsu-Ogura Y, Matsushita M, et al. High incidence of metabolically active brown adipose tissue in healthy adult humans: effects of cold exposure and adiposity. Diabetes. 2009;58:1526–1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, Vanhommerig JW, Smulders NM, et al. Cold-activated brown adipose tissue in healthy men. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1500–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Virtanen KA, Lidell ME, Orava J, et al. Functional brown adipose tissue in healthy adults. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1518–1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zingaretti MC, Crosta F, Vitali A, et al. The presence of UCP1 demonstrates that metabolically active adipose tissue in the neck of adult humans truly represents brown adipose tissue. FASEB J. 2009;23:3113–3120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leonardsson G, Steel JH, Christian M, et al. Nuclear receptor corepressor RIP140 regulates fat accumulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:8437–8442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pan D, Fujimoto M, Lopes A, Wang YX. Twist-1 is a PPARδ-inducible, negative-feedback regulator of PGC-1α in brown fat metabolism. Cell. 2009;137:73–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vegiopoulos A, Muller-Decker K, Strzoda D, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 controls energy homeostasis in mice by de novo recruitment of brown adipocytes. Science. 2010;328:1158–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Guerra C, Koza RA, Yamashita H, Walsh K, Kozak LP. Emergence of brown adipocytes in white fat in mice is under genetic control. Effects on body weight and adiposity. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:412–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cousin B, Cinti S, Morroni M, et al. Occurrence of brown adipocytes in rat white adipose tissue: molecular and morphological characterization. J Cell Sci. 1992;103(Pt 4):931–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bostrom P, Wu J, Jedrychowski MP, et al. A PGC1-α-dependent myokine that drives brown-fat-like development of white fat and thermogenesis. Nature. 2012;481:463–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cao L, Liu X, Lin EJ, et al. Environmental and genetic activation of a brain-adipocyte BDNF/leptin axis causes cancer remission and inhibition. Cell. 2010;142:52–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cao L, Lin EJ, Cahill MC, Wang C, Liu X, During MJ. Molecular therapy of obesity and diabetes by a physiological autoregulatory approach. Nat Med. 2009;15:447–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cao L, Choi EY, Liu X, et al. White to brown fat phenotypic switch induced by genetic and environmental activation of a hypothalamic-adipocyte axis. Cell Metab. 2011;14:324–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bessesen DH. Regulation of body weight: what is the regulated parameter? Physiol Behav. 2011;104:599–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van Dijk G, Buwalda B. Neurobiology of the metabolic syndrome: an allostatic perspective. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;585:137–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cao L, During MJ. What is the brain-cancer connection? Annu Rev Neurosci. 2012;35:331–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cao L, Jiao X, Zuzga DS, Liu Y, Fong DM, Young D, During MJ. VEGF links hippocampal activity with neurogenesis, learning and memory. Nat Genet. 2004;36:827–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu X, Magee D, Wang C, et al. Adipose tissue insulin receptor knockdown via a new primate-derived hybrid recombinant AAV serotype. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2014:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rooks CR, Penn DM, Kelso E, Bowers RR, Bartness TJ, Harris RB. Sympathetic denervation does not prevent a reduction in fat pad size of rats or mice treated with peripherally administered leptin. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R92–R102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gerber HP, Hillan KJ, Ryan AM, et al. VEGF is required for growth and survival in neonatal mice. Development. 1999;126:1149–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. He W, Barak Y, Hevener A, et al. Adipose-specific peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ knockout causes insulin resistance in fat and liver but not in muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15712–15717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sung HK, Doh KO, Son JE, et al. Adipose vascular endothelial growth factor regulates metabolic homeostasis through angiogenesis. Cell Metab. 2013;17:61–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-δδC(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sackmann-Sala L, Berryman DE, Munn RD, Lubbers ER, Kopchick JJ. Heterogeneity among white adipose tissue depots in male C57BL/6J mice. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20:101–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Giordano A, Frontini A, Murano I, et al. Regional-dependent increase of sympathetic innervation in rat white adipose tissue during prolonged fasting. J Histochem Cytochem. 2005;53:679–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sun K, Kusminski CM, Scherer PE. Adipose tissue remodeling and obesity. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2094–2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sun K, Kusminski CM, Luby-Phelps K, et al. Brown adipose tissue derived VEGF-A modulates cold tolerance and energy expenditure. Mol Metab. 2014;3:474–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shimizu I, Aprahamian T, Kikuchi R, et al. Vascular rarefaction mediates whitening of brown fat in obesity. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:2099–2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Xue Y, Petrovic N, Cao R, et al. Hypoxia-independent angiogenesis in adipose tissues during cold acclimation. Cell Metab. 2009;9:99–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sun K, Asterholm IW, Kusminski CM, et al. Dichotomous effects of VEGF-A on adipose tissue dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:5874–5879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lee CV, Liang WC, Dennis MS, Eigenbrot C, Sidhu SS, Fuh G. High-affinity human antibodies from phage-displayed synthetic Fab libraries with a single framework scaffold. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:1073–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liang WC, Wu X, Peale FV, et al. Cross-species vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-blocking antibodies completely inhibit the growth of human tumor xenografts and measure the contribution of stromal VEGF. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:951–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sullivan LA, Carbon JG, Roland CL, et al. r84, a novel therapeutic antibody against mouse and human VEGF with potent anti-tumor activity and limited toxicity induction. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Corada M, Mariotti M, Thurston G, et al. Vascular endothelial-cadherin is an important determinant of microvascular integrity in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9815–9820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lyons WE, Mamounas LA, Ricaurte GA, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor-deficient mice develop aggressiveness and hyperphagia in conjunction with brain serotonergic abnormalities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:15239–15244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Eide FF, Vining ER, Eide BL, Zang K, Wang XY, Reichardt LF. Naturally occurring truncated trkB receptors have dominant inhibitory effects on brain-derived neurotrophic factor signaling. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3123–3129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Himms-Hagen J, Cui J, Danforth E, Jr, et al. Effect of CL-316,243, a thermogenic β3-agonist, on energy balance and brown and white adipose tissues in rats. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:R1371–R1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Petrovic N, Walden TB, Shabalina IG, Timmons JA, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Chronic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) activation of epididymally derived white adipocyte cultures reveals a population of thermogenically competent, UCP1-containing adipocytes molecularly distinct from classic brown adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7153–7164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wilson-Fritch L, Nicoloro S, Chouinard M, et al. Mitochondrial remodeling in adipose tissue associated with obesity and treatment with rosiglitazone. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1281–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ohno H, Shinoda K, Spiegelman BM, Kajimura S. PPARγ agonists induce a white-to-brown fat conversion through stabilization of PRDM16 protein. Cell Metab. 2012;15:395–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Papetti M, Herman IM. Mechanisms of normal and tumor-derived angiogenesis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C947–C970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhang QX, Magovern CJ, Mack CA, Budenbender KT, Ko W, Rosengart TK. Vascular endothelial growth factor is the major angiogenic factor in omentum: mechanism of the omentum-mediated angiogenesis. J Surg Res. 1997;67:147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Liekens S, De Clercq E, Neyts J. Angiogenesis: regulators and clinical applications. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;61:253–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zwetsloot KA, Westerkamp LM, Holmes BF, Gavin TP. AMPK regulates basal skeletal muscle capillarization and VEGF expression, but is not necessary for the angiogenic response to exercise. J Physiol. 2008;586:6021–6035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Aleffi S, Petrai I, Bertolani C, et al. Up-regulation of proinflammatory and proangiogenic cytokines by leptin in human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2005;42:1339–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Arany Z, Foo SY, Ma Y, et al. HIF-independent regulation of VEGF and angiogenesis by the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1α. Nature. 2008;451:1008–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tang W, Zeve D, Suh JM, et al. White fat progenitor cells reside in the adipose vasculature. Science. 2008;322:583–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tran KV, Gealekman O, Frontini A, et al. The vascular endothelium of the adipose tissue gives rise to both white and brown fat cells. Cell Metab. 2012;15:222–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bagchi M, Kim LA, Boucher J, Walshe TE, Kahn CR, D'Amore PA. Vascular endothelial growth factor is important for brown adipose tissue development and maintenance. FASEB J. 2013;27:3257–3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fong GH, Rossant J, Gertsenstein M, Breitman ML. Role of the Flt-1 receptor tyrosine kinase in regulating the assembly of vascular endothelium. Nature. 1995;376:66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ema M, Takahashi S, Rossant J. Deletion of the selection cassette, but not cis-acting elements, in targeted Flk1-lacZ allele reveals Flk1 expression in multipotent mesodermal progenitors. Blood. 2006;107:111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Nishio M, Yoneshiro T, Nakahara M, et al. Production of functional classical brown adipocytes from human pluripotent stem cells using specific hemopoietin cocktail without gene transfer. Cell Metab. 2012;16:394–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lee YH, Petkova AP, Mottillo EP, Granneman JG. In vivo identification of bipotential adipocyte progenitors recruited by β3-adrenoceptor activation and high-fat feeding. Cell Metab. 2012;15:480–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gupta RK, Mepani RJ, Kleiner S, et al. Zfp423 expression identifies committed preadipocytes and localizes to adipose endothelial and perivascular cells. Cell Metab. 2012;15:230–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]