Abstract

Ependymocytes are one of the energy-sensing cells that regulate animal reproduction through their responsiveness to changes in extracellular glucose levels and the expression of pancreatic-type glucokinase and glucose transporter 2, which play a critical role in sensing blood glucose levels in pancreatic β-cells. Molecular mechanisms underlying glucose sensing in the ependymocytes remain poorly understood. The AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a serine/threonine kinase highly conserved in all eukaryotic cells, has been suggested to be an intracellular fuel gauge that detects cellular energy status. The present study aims to clarify the role AMPK of the lower brainstem ependymocytes has in sensing glucose levels to regulate reproductive functions. First, we will show that administration of 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside, an AMPK activator, into the 4th ventricle suppressed pulsatile LH release in female rats. Second, we will demonstrate the presence of AMPK catalytic subunit immunoreactivities in the rat lower brainstem ependymocytes. Third, transgenic mice were generated to visualize the ependymocytes with Venus, a green fluorescent protein, expressed under the control of the mouse vimentin promoter for further in vitro study. The Venus-labeled ependymocytes taken from the lower brainstem of transgenic mice revealed that AMPK activation by 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside, an AMPK activator, increased in vitro intracellular calcium concentrations. Taken together, malnutrition-induced AMPK activation of ependymocytes of the lower brainstem might be involved in suppression of GnRH/LH release and then gonadal activities.

Availability of metabolic fuels is considered to be detected by an energy sensor located in district brain regions to control the gonadal activity in mammals (1). Experimentally, food restriction suppresses gonadotropin secretion in various mammalian species, such as cows (2), sheep (3), goats (4), rats (5), mice (6), and monkeys (7). These responses to negative energy balance would be strategic adaptations by animals to reserve energy for individual survival by sparing energy for reproduction. In addition to several hypothalamic areas, such as the hypothalamic ventromedial nucleus, paraventricular nucleus (PVN), arcuate nucleus, and lateral hypothalamic area (8–10), the lower brainstem has also been suggested to be an energy-sensing region, because food intake is increased by an infusion of 5-thio-D-glucose, an antimetabolite of glucose, into the 4th cerebroventricle (4V), but not into the 3V, in rats with an obstruction of the connection between the 3V and 4V (11). Administration of 2-deoxyglucose, another antimetabolite of glucose, into the 4V also suppressed pulsatile LH secretion (12). These results support the notion that a glucose-sensing system is located in the lower brainstem to sense negative energy balance, and to control GnRH and then gonadotropin release.

Our previous studies suggest that ependymocytes located in the lower brainstem are candidate cells for sensing glucose availability and regulating gonadal activities (13). Ependymocytes are ciliated-glial cells, lining the ventricular surface of the central nervous system (CNS) and interfacing with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). For instance, the changes in CSF glucose levels correspond to changes in blood glucose levels (14–17), so that CSF-interfacing ependymocytes might have a role in monitoring the circulating levels of energy molecules, such as glucose. The previous morphological studies demonstrated that ependymocytes in rats showed both a pancreatic type of glucokinase (GK) and glucose transporter 2-immunoreactivity (ir) (18, 19), which play a key role in sensing blood glucose levels in pancreatic β-cells (20). The hindbrain ependymocytes might sense lowered glucose availability, because in vitro intracellular calcium concentrations ([Ca2+]i) in the lower brainstem GK-ir ependymocytes increase in response to a decrease in extracellular glucose levels (21). Hindbrain ependymocytes might also be equipped with mechanism sensing ketone bodies, a major fuel under malnutrition, to down-regulate gonadotropin release (17, 22). This is because a ketone body transporter, monocarboxylate transporter 1, is highly expressed on the hindbrain ependymocytes, and because 4V administration of a ketone body, 3-hydroxybutrate, decreased pulsatile LH secretion (17, 22). Thus, hindbrain ependymocytes are candidate as energy sensors that integrate whole-body energetic information and convey it to the center controlling reproduction. To support our idea that ependymocytes participate in energy sensing, previous studies indicated that the hypothalamic tanycyte, another type of ependymocyte, had an increase in the [Ca2+]i in response to an increase in extracellular glucose levels (23, 24).

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling has been known to be involved in the regulation of energy balance at the whole-body level by responding to hormonal and nutrient signals in both peripheral tissues and the CNS (25). AMPK has been termed an intracellular fuel gauge, because its activity is up-regulated by an increase in cellular AMP to ATP ratio and then by upstream kinases (26). AMPK activation in the CNS causes short- and long-term changes in intracellular molecules, such as an increase in [Ca2+]i in neuropeptide Y neurons (27, 28), up- and down-regulations of adipogenic enzymes in hypothalamic ventromedial nucleus neurons (29), and transcriptional changes in cultured hypothalamic neurons (30). Minokoshi et al have reported that dominant-negative AMPK expression in the hypothalamus reduces food intake and body weight (31). Further, glucoprivic feeding was blocked by 4V administration of an AMPK inhibitor (32). These results suggest that AMPK is a key molecule in the hindbrain that senses the negative energy balance so as to control energy homeostasis. Thus, we hypothesized that AMPK activity plays a key intracellular role in sensing lowered energy availability to suppress mammalian reproduction. Elucidating the role of AMPK would be of benefit to understanding the central mechanism involved in menstrual disturbance in eating disorders (33) and the malnutrition-induced suppression of gonadal function often seen in the milking cow (34).

The present study, thus, aimed to investigate whether AMPK in ependymocytes of the lower brainstem plays a role in sensing negative energy balance to regulate GnRH/LH release. To address the issue, we examined whether a local administration of an AMPK activator into the 4V suppresses pulsatile LH secretion in female rats. We also examined the immunohistochemical localization of AMPK in female rat brain to show that the lower brainstem is equipped with AMPK. Further, to determine whether ependymocytes directly respond to the AMPK activator, we analyzed in vitro changes in [Ca2+]i responses to AMPK activation in the visualized ependymocytes taken from the lower brainstem of newly generated transgenic mice, in which a green fluorescent protein Venus was specifically expressed under the promoter of vimentin gene (Vim) (a marker of ependymocytes).

Materials and Methods

Animals

Rats and mice were housed in a controlled environment (14-h light, 10-h darkness with lights-on at 5 am, 23 ± 3°C) and had free access to food (CE-2; CLEA Japan, Inc) and water. Adult female Wistar-Imamichi strain rats (10–13 wk old, 213–268 g; Charles River Laboratories Japan, Inc) were used for in vivo experiments to investigate the effect of 4V 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside, an AMPK activator (AICAR) administration on pulsatile LH release and for dual-label immunohistochemistry for Vim and AMPK. Female rats having shown at least 2 consecutive estrous cycles were bilaterally ovariectomized (OVX), and received a sc Silastic tubing (1.5 mm inner diameter; 3.0 mm outer diameter; 25 mm in length; Dow Corning) containing estradiol-17β (E2) (Sigma) dissolved in peanut oil at 20 μg/mL 1 week before the above-mentioned experiments. We have previously demonstrated that rats subjected to this E2 treatment had diestrous plasma E2 levels (35). The E2 treatment was chosen because it causes significant suppression of LH pulses when animals are subjected to 48-hour fasting (35) and enhances glucoprivic suppression of LH pulses (36). Adult female Vim-Venus transgenic mice (10–15 wk old, 27–36 g) newly generated in the present study were used for in vitro measurement of [Ca2+]i in lower brainstem ependymocytes. All surgical procedures were performed under isoflurane (Abbott Japan Co, Ltd) anesthesia. The present study was approved by the Committee on Animal Experiments of the Graduate School of Bioagricultural Sciences, Nagoya University.

Brain surgery and blood sampling for in vivo experiment in rats

One week before blood sampling, estradiol-primed OVX (OVX+E2) rats were implanted with a stainless-steel guide cannula (22G; Plastic One) into the 4V with the tip end at 12.5 mm posterior and 8.3 mm ventral to the bregma at midline, as previously described (12). AICAR (Calbiochem), was dissolved in ultrapure water at 2 μmol/8 μL immediately before administration. The present dose of AICAR (250 nmol/μL) was chosen according to the previous studies, which showed that 4V injection of AMPK activator (6.7–387.6 nmol/μL) induced feeding behavior or blocked the anorexigenic effect of leptin on feeding behavior in male rats (32, 37). Free-moving conscious rats were infused with AICAR or ultrapure water into the 4V at the rate of 0.25 μL/min for 32 minutes, with a microsyringe pump (EICOM) through an internal cannula (28G; Plastic One) immediately after the onset of blood sampling. Blood samples (100 μL) were collected through the right jugular vein for 3 hours from 1 pm at 6-minute intervals through an indwelling atrial cannula (silicon tubing, inner diameter, 0.5 mm; outer diameter, 1.0 mm; Shin-Etsu Polymer) that had been inserted on the day before the blood sampling. Each blood sample was replaced with an equivalent volume of washed red blood cells obtained from other rats to keep the hematocrit constant. No food was available during AICAR infusion and blood sampling to avoid the influence of food intake on LH secretion and blood glucose levels. Plasma samples were obtained by an immediate centrifugation and stored at −20°C until assayed for LH. Plasma glucose levels were measured in an additional volume (50 μL) of blood samples obtained at 12- and 30-minute intervals during the first and last 2 hours of the sampling period, respectively.

At the end of blood sampling, animals were infused with 3% brilliant blue into the 4V at the rate of 0.25 μL/min for 32 minutes through the internal cannula to verify the cannula placement and diffusion area of the drug (Supplemental Table 1). Only the data obtained from animals with right cannula placement were analyzed.

LH and glucose assays

Plasma LH concentrations were determined by a double-antibody RIA as previously described (22) with a rat LH RIA kit provided by the National Hormone and Peptide Program and were expressed in terms of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases rLH PR-3. The least detectable level in 50-μl plasma samples was 0.156 ng/mL, and the intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were 4.4% and 6.9% at 1.2 ng/mL, respectively. Plasma glucose concentrations were determined by the glucose oxidase method using a commercial kit (Glucose C-Test; Wako), as previously described (6).

Generation of Vim-Venus transgenic mice

We have generated transgenic mice to visualize ependymocytes with Venus, a green fluorescent protein, expressed under the control of the mouse Vim promoter. The mouse Vim promoter region (−3221 to +44 bp from the ATG start site) was amplified from purified mice genomic DNA (C57/BL) using forward primers ACGCGTGGATCCTTGGCTGTCCTTGA and reverse primer GTCGACAATCGTAGGAGCGCTGGGGT (accession number D50805), based on the sequence reported previously (38). The mouse Vim promoter linked to the coding sequence for Venus and the Simian virus 40 polyadenylation signal was used for the transgenes. The linearized transgenes were purified by precipitation with ethanol and injected into fertilized eggs of the B6D2F1 mouse strain. Microinjected eggs were implanted into the oviducts of pseudopregnant (Slc:ICR) foster mothers. The presence of the transgene was determined by PCR analysis of mouse genomic DNA isolated from ear-punched tissue using forward primer GTTCAGCGTGTCCGGCGA and reverse primer GCGGTCACGAACTCCAGC. F1 and F2 mice with transgenes were identified by PCR analysis.

Preparation for lower brainstem Vim-Venus cells of transgenic mice for in vitro [Ca2+]i measurement

After decapitation, the mouse brain was rapidly removed, and tissues containing the ependymal layer of the lower brainstem were dissected out. Dissected tissues were washed with an ice-cold 1:1 mixture of 0.01M PBS (pH 7.4) and supplemented DMEM (31053-028; GIBCO) along with 4mM L-glutamine, 1mM sodium pyruvate (GIBCO), and 2% penicillin/streptomycin mixture (GIBCO). Tissues were then incubated in 0.15-U/mL papain (Worthington) in PBS containing 0.2-mg/mL BSA, 0.2-mg/mL L-cystein, and 1.8-mg/mL glucose for 30 minutes at 37°C, followed by gentle mechanical dispersion in the supplemented DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (NICHIREI) at room temperature, and then were filtered through a 70-μm pore size nylon mesh (BD Biosciences). A cell pellet was obtained by centrifugation at 800 rpm 2 times for 5 minutes and then resuspended in supplemented DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum. The cells seeded on glass bottom dishes (Iwaki) coated with poly-l-lysine (Sigma) were used for further [Ca2+]i measurement.

Effects of AICAR on in vitro [Ca2+]i in lower brainstem ependymocytes

The change in [Ca2+]i was measured in the ependymocytes of the lower brainstem taken from Vim-Venus mice. Fura-PE3 was loaded into the cells by incubating with 2μM Fura-PE3 (Fura-2 LR (AM), 0108; TEFLabs) in HEPES-buffered Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer (HKRB) (129mM NaCl, 5.0mM NaHCO3, 3.7mM KCl, 1.2mM KH2PO4, 1.8mM CaCl2, 1.2mM MgSO4, 5.5mM glucose, and 10mM HEPES [pH 7.3]) containing 0.1% Cremophor EL for 1 hour at 37°C. The cells were washed 3 times with HKRB and kept at 37°C throughout the [Ca2+]i measurement. They were then superfused with a series of mediums in the next order: HKRB for 3 minutes, 200μM AICAR (Sigma) in HKRB for 20 minutes, HKRB for 15 minutes, 200μM AICAR in HKRB for 20 minutes, and then 100mM KCl. The present dose of AICAR (200μM) was chosen according to the previous in vitro study, which revealed that the same dose of AICAR increased [Ca2+]i in mouse neuropeptide Y neurons (28). Fluorescence images were taken every 10 seconds with a fluorescent microscope (Olympus) and an Intensified CCD camera (Hamamatsu Photonics), with an excitation wavelength at both 340 and 380 nm. Motion artifacts during calcium measurement were subjected to an automatic subpixel registration algorithm using StackReg plugin in ImageJ software (United States National Institutes of Health). Ratio images were also obtained by ImageJ software.

Immunohistochemistry

OVX+E2 rats and Vim-Venus transgenic mice were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital (Dainippon Pharma) and perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich Japan) in 0.05M phosphate buffer (PB). Brains were removed immediately, postfixed in the same fixative overnight at 4°C, and then immersed in 30% sucrose in 0.05M PB at 4°C. Frozen frontal sections (50 μm) were obtained with a cryostat. To identify the cell type of Venus-positive cells, some of the dispersed cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.05M PB for 10 minutes. Free-floating brain sections and cells obtained from the lower brainstem of Vim-Venus transgenic mice were subjected to immunohistochemistry with anti-Vim antibody (Merck Millipore). Rat brain sections were subjected to double-immunohistochemistry with anti-Vim antibody and antiphospho-AMPKα (P-AMPKα) antibody (Cell Signaling Technology Japan). The sources and concentrations of antibodies used in these studies are listed in Supplemental Table 2. To visualize P-AMPKα and Vim, the sections were then incubated with secondary antibodies, Alexa Fluor 488- for P-AMPKα or Alexa Fluor 594-sencondary antibodies for Vim. Some Vim-Venus cells were counterstained with DNA staining, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (1:100 000; Sigma). Fluorescence images of the brain section or the Vim-Venus cells were obtained with an Apotome microscope (Carl Zeiss) or with laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSM5 Pascal; Carl Zeiss). In Supplemental Figures 1, A–C, and 2C, 10 images of different parts of the same brain section were taken using the Apotome microscope, and were then combined in Photoshop CS (Adobe Systems) using the Automate Photomerge tool.

Some brain sections taken from OVX+E2 rats were stained with diaminobenzidine (DAB). After incubation with the anti-P-AMPKα antibody, the sections were treated with biotin-conjugated goat antirabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories) for 1 hour. They were then incubated with an avidin-biotinylated horseradish peroxidase complex (VECTASTAIN Elite ABC Standard kit; Vector Laboratories) for 30 minutes according to the manufacturer's instructions. The sections were then visualized with 0.02% DAB mixed with 0.006% hydrogen peroxide for 1 minute. The bright-field images of the sections were obtained with an optical microscope (BX53; Olympus).

Specificity of the anti-P-AMPKα antibody was confirmed by an absorption test and Western blotting. For the absorption test, an antibody solution containing 0.26 μg of antibodies was incubated at 4°C overnight with 18 μg of the synthetic blocking peptide (Cell Signaling Technology), and then used for immunohistochemistry. Western blottings with anti-P-AMPKα antibody revealed the single band to be of expected size (62 kDa) in protein sample purified from tissues containing ependymocytes around the 4V or arcuate nucleus in rats (Supplemental Figure 3).

Data analysis and statistics

LH pulses were identified by the PULSAR computer program (39) as previously described (40). Statistical differences in the mean LH concentrations, baseline levels of LH and the frequency and amplitude of LH pulses between AICAR- and vehicle-treated groups were determined by Student's t test. Statistical differences in plasma glucose concentrations were determined by two-way ANOVA with repeated measures.

Significant changes in [Ca2+]i were detected by Igor Pro software (Wavemetrics). Because the baseline relative [Ca2+]i levels gradually increased, the background increase was removed with the Igor Pro multipeak fitting package. Specifically, after subtracting the best-fit cubic baseline from the ratio data of the Venus-positive cells, the Gaussian function was used in the fitting procedure for multiple overlapping peaks with the package. The computed peaks detected by the procedures were considered as significant change in [Ca2+]i. The value of the peak area (the relative increase in [Ca2+]i levels) calculated for each peak by the package was then used for further statistical analysis. Statistical differences in the area of computed [Ca2+]i increases were determined by Mann-Whitney U test. The viability of the cells was determined at the end of each experiment by an increase in [Ca2+]i response to KCl. Data were taken only from cells that responded to KCl stimulation.

Results

Effects of 4V AICAR administration on LH pulses and blood glucose levels in female rats

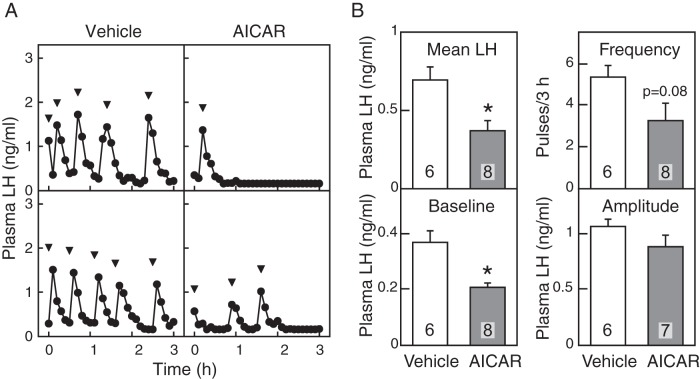

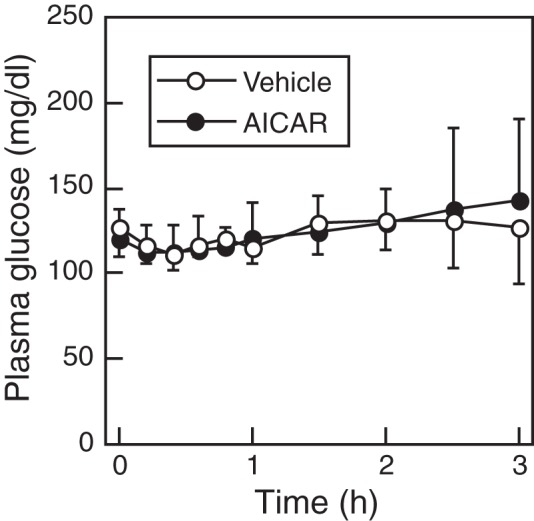

Figure 1A shows plasma LH profiles of representative individuals in vehicle- and AICAR-treated groups. The 4V administration of AICAR, an AMPK activator, suppressed pulsatile LH release in 5 out of 8 OVX+E2 rats. The mean and baseline levels of LH in AICAR-treated group were significantly (P < .05, Student's t test) lower than those of the vehicle-treated controls (Figure 1B). Although LH pulse frequency was not significantly affected by AICAR treatment, it tended to be decreased by it (P = .08). The amplitude of LH pulses was comparable between groups. No significant difference was found in plasma glucose concentrations between vehicle- and AICAR-treated groups throughout the 3-hour sampling period (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Effect of AMPK activation on LH release in estradiol-primed OVX rats. A, Plasma LH profiles of 2 representative animals treated with 4V injection of vehicle (UPW, 8 μL) or AICAR (2 μmol/8 μL). Blood samples were collected every 6 minutes for 3 hours while vehicle or AICAR infused into the 4V (flow rate, 0.25 μL/min for 32 min). Arrowheads indicate peaks of LH pulses identified by PULSAR computer program. B, Mean LH concentrations, baseline levels of LH, and the frequency and amplitude of LH pulses were calculated for a 3-hour sampling period of vehicle-treated (opened bars) and AICAR-treated (solid bars) groups. Values are mean ± SEM. The number in each column indicates the number of animals used. Asterisks indicate significant differences from vehicle-treated controls (P < .05, Student's t test).

Figure 2.

Changes in mean plasma glucose levels in vehicle-treated or AICAR-treated estradiol-primed OVX rats. Concentrations were determined every 12 minutes for the first 2 hours and every 30 minutes for last 2 hours. Values are mean ± SEM (vehicle, n = 6; AICAR, n = 8).

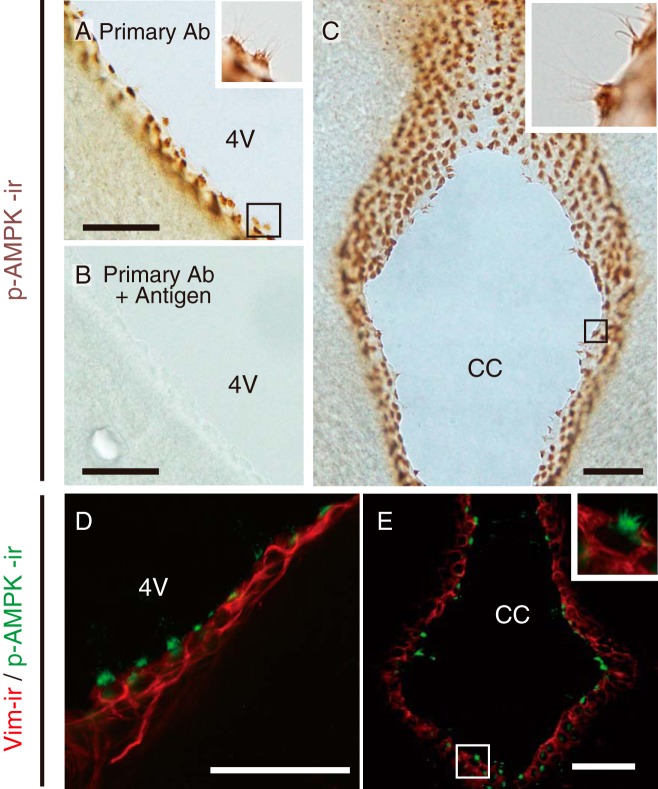

Localization of AMPK-irs in the rat brain

Figure 3 shows the immunohistochemical localization of an AMPK catalytic subunit, P-AMPKα, in rat brain. P-AMPKα-irs were found in the cilia on ependymocytes lining the walls of the 4V (Figure 3A) and central canal (CC) (Figure 3B). Similarly, cilia around the 3V and lateral ventricles also demonstrated P-AMPKα-irs (Supplemental Figure 4). Weak p-AMPKα-irs were found in some cells in the A1/C1 region of the lower brainstem (Supplemental Figure 4). The immunoreactivity to anti-P-AMPKα antibody was eliminated in brain sections around the 4V, which were reacted with the absorbed antiserum (Figure 3C). Double staining with anti-P-AMPKα and anti-Vim antibodies revealed that Vim-ir ependymocytes around the 4V and CC have P-AMPKα-irs in the cilia (Figure 3, D and E).

Figure 3.

Localization of P-AMPKα-irs in ependymocytes of the lower brainstem in female rats. A and B, Representative DAB staining images showing P-AMPKα-ir (brown) around the wall of 4V (A) and CC (B). Insets in A and B, High-magnification images of areas indicated, respectively. C, Specificity of P-AMPKα antibody labeling in rat ependymocytes located around 4V. Positive P-AMPKα-ir observed in ependymocytes were eliminated by preadsorption of anti-P-AMPKα antibody with the synthetic antigen. D and E, Representative confocal fluorescence images showing P-AMPKα-ir (green) and Vim-ir (red) around the wall of 4V (D) and CC (E). Insets in E, High-magnification images of areas indicated. Scale bars, 50 μm.

Confirmation of specificity of Vim-Venus transgenic mice

Two founders of transgenic mice (lines 01 and 02) were generated, and both lines exhibited specific Venus expression patterns in cells surrounding the 4V and CC. One line (01) of Vim-Venus transgenic mice was used for further experiments. PCR analysis showed the band to be of expected size (4.5 kb), indicating that the transgenic line carried a full-length Vim-Venus DNA fragment (Figure 4, A and B). Venus expression was observed in the cells surrounding the 4V and CC of Vim-Venus transgenic mice (Figure 4C, green). Venus fluorescence was also detected in tanycyte-like processes around the 4V (Figure 4C, green, upper). Merged pictures showed that Venus fluorescence was colocalized with Vim-irs in the lower brainstem of Vim-Venus mice (Figure 4C, merged). Vim-Venus mice showed no Venus fluorescence in other brain areas where Vim was expressed, such as the area postrema (Supplemental Figure 1). The other line (02) also exhibited a specific Venus expression pattern in cells surrounding a part of the 4V and CC (Supplemental Figure 2, A and B). We have chosen line 01 of Vim-Venus mice for further experiments because of the lower level of background fluorescence in that line compared with line 02 (Supplemental Figure 2C). The difference in the background could be due to the position effect of transgene. In isolated cells taken from the lower brainstem of Vim-Venus mice, 62 out of 191 Vim-ir cells (32.5%) showed Venus fluorescence (Figure 4D). It should be noted that all Venus-positive cells showed Vim-ir in the isolated cells.

Figure 4.

Generation of Vim-Venus transgenic mice. A, Schematic illustration of construct for the generation of Vim-Venus transgenic mice. pA indicates the Simian virus 40 polyadenylation signal. B, Genomic PCR result for detecting Vim-Venus DNA construct (4.5 kb) in purified genome of Vim-Venus transgenic (Tg) mice with size markers (M). C, Confocal images showing Venus fluorescence (green) and Vim-ir (red) around the wall of 4V and CC in female transgenic mice. Computer-aided merged images of Venus fluorescence and Vim-ir are shown on the right panels. Insets in C, High-magnification images the areas indicated, respectively. Scale bars, 50 μm. D, Colocalization of Venus fluorescence and Vim-ir in isolated cells taken from lower brainstem of Vim-Venus mice (arrows). 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue) was used for nuclear staining. Pie chart shows the percentage of Vim-ir-positive by Venus-positive cells. Scale bars, 10 μm.

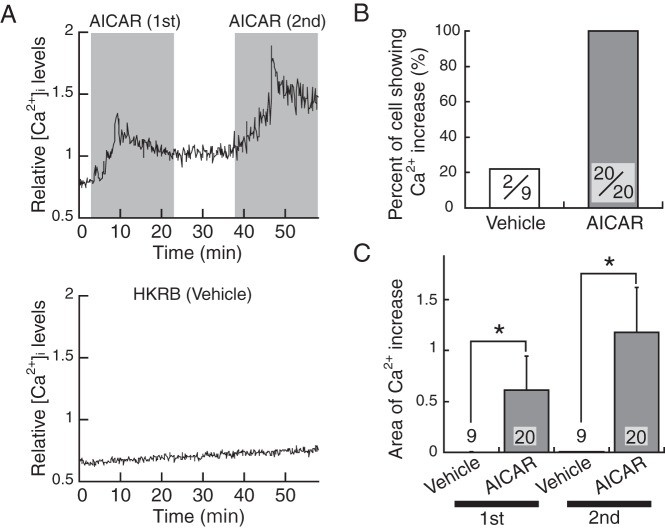

Increase in [Ca2+]i in ependymocytes in response to AMPK activation

Figure 5A shows a representative pattern of changes in [Ca2+]i in Venus-positive cells taken from the lower brainstem of Vim-Venus mice. [Ca2+]i increased in response to the first and second AICAR administration (Figure 5A, upper panel), whereas it remained at the baseline level throughout the experimental period in vehicle-treated group (Figure 5A, lower panel). All 20 Venus-positive cells responded to AICAR treatment (Figure 5B). Of AICAR-responsive cells, 8 (40%) demonstrated repeated increase in [Ca2+]i, and the other 12 cells (60%) showed an increase once after the first or second AICAR administration. As shown in Figure 5C, the computed areas of increase in [Ca2+]i in AICAR-treated cells (0.608 ± 0.339 for the first 20 min and 1.17 ± 0.44 for the second 20 min; n = 20) were significantly (P < .05, Mann-Whitney U test) higher than vehicle-treated cells (0.002 ± 0.002 for the first 20 min and 0.005 ± 0.005 for the second 20 min; n = 9).

Figure 5.

Response to AMPK activator of [Ca2+]i in Venus-positive ependymocytes of lower brainstem in Vim-Venus mice. A, Representative changes in relative [Ca2+]i level of AICAR-treated (upper, shaded area) and vehicle (HKRB medium)-treated (bottom) cell. B, Percentage of Venus-positive ependymocytes with increase in response to AICAR administration. The number in each column indicates ratio of cells showing Ca2+ increase out of all Venus-positive cells used. Values are mean ± SEM. C, The area of computed Ca2+ increases of vehicle-treated (opened bars) and AICAR-treated (solid bars) cells. First and second mean the first and second 20 minutes of vehicle or AICAR administrations. The number in each column indicates the number of Venus-positive cells used. Values are mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate significant difference from vehicle-treated controls (P < .05, Mann-Whitney U test).

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that AMPK located in the ependymocytes in the lower brainstem function as energy sensors to down-regulate GnRH/LH release under malnutrition, by the fact that the administration of an AMPK activator into the 4V suppresses in vivo pulsatile LH secretion in rats, and the AMPK activator increased in vitro [Ca2+]i in the ependymocytes taken from the lower brainstem of Vim-Venus transgenic mice. It should be noted that the activation site of in vivo AMPK was limited to within the lower brainstem, because the diffusion of dye after the experiment was observed only within the 4V or posterior to the 4V. AMPK is an intracellular fuel gauge activated by an increase in the intracellular level of AMP to ATP ratio (25, 41), which increases in response to malnutrition. Thus, the current results suggest that ependymocytes located in the lower brainstem sense lowered energy availability through an activation of AMPK to suppress gonadotropin secretion. The present study also showed that an active form of AMPK, P-AMPKα, was found abundantly in the cilia of ependymocytes. This indicates that AICAR infused into the 4V may act on AMPK located in ependymal cilia of the lower brainstem. Taken together, the present study suggests that an activation of AMPK in ependymocytes located in the lower brainstem relays negative energy information to the mechanism regulating GnRH/LH secretion to suppress reproductive functions. It should be noted that ependymocytes around the wall of 3V may also have a role of detecting glucose, because AMPK-ir was observed in ependymal cilia of 3V in the present study.

The present results are well consistent with those of the previous studies in which pharmacological inhibition of hindbrain AMPK activity suppressed food intake and body weight gain in rats (37). Thus, it is likely that local AMPK activation of hindbrain ependymocytes is involved in the regulation of both reproduction and feeding during malnutrition. Ependymocytes are equipped with 2 other glucose-sensing system components: glucose transporter 2 and GK (18, 42). They play a central role in sensing blood glucose levels in pancreatic β-cells (20), in which changes in the intracellular AMP to ATP ratio induced by glucose metabolism play a key role for initiating the glucose-sensing system to secrete insulin (43). Likewise, decrease in the extracellular glucose level might increase the AMP to ATP ratio in ependymocytes, thereby activating AMPK. Taken together, these results support the notion that AMPK of ependymocytes located in the lower brainstem monitor systemic glucose availability to control GnRH/LH secretion. It should be noted that the AMPK activator may reach distant brain regions, such as the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS). The NTS has been suggested to be involved in appetite and energy regulation; food-deprived rats showed a significant increase in AMPK activity in NTS-enriched lysates compared with those in ad libitum-fed rats (37). This therefore suggests that AMPK activation in the NTS could also be involved in AICAR-induced LH suppression (37). Interestingly, AMPK is involved in several other actions such as regulation of cell polarity, transcription, cell proliferation and migration (44, 45). AICAR-induced LH suppression could also be related to AMPK-induced energy-independent factors.

Venus expression in the present transgenic mice was limited in the ependymocytes, and in vitro AICAR administration increased [Ca2+]i in the Venus-positive cells, suggesting that the current AICAR administration increased [Ca2+]i in the ependymocytes lining the 4V and CC of the lower brainstem. The increase in [Ca2+]i by AMPK activation in the ependymocytes suggests that some signal molecules are released from the ependymocytes to relay lowered energetic information to the downstream neural circuit to control reproduction. In support of this, previous morphological studies revealed that ependymocytes might have secretory functions because of the presence of the neurosecretory vesicles within them (46–48). Indeed, glial cells are shown to cause [Ca2+]i elevations to release chemical transmitters (ie, gliotransmitter) in response to extracellular stimuli, such as excitatory amino acids (for review, see Ref. 49). Furthermore, ependymocytes release gliotransmitters (eg, basic fibroblast growth factor and ATP) in response to changes in extracellular glucose levels (24, 50). These facts, taken together with our current results, strongly suggest that ependymocytes sense nutrients in the CSF and relay nutritional information to downstream neurons by secreting specific gliotransmitters via AMPK-activated Ca2+ signaling. Ependymal cilia may have a role in sensing energy, because a great amount of AMPK was located in ependymal cilia. This notion is consistent with the previous reports, suggesting that mammalian cilia, such as primary and motile cilia, have sensory functions (51). Thus, AMPK in the ependymal cilia contacting CSF might sense a change in nutritional cues in the CSF, where changes in nutrient molecule levels are correlated with those in the whole body.

The present 4V injection of an AMPK activator failed to affect the blood glucose level, suggesting that glucose sensing in the 4V ependymocytes specializes in controlling reproductive function and feeding but not in glucose homeostasis. This notion is consistent with our previous study, in which reduction of hindbrain GK activity suppressed pulsatile LH release but did not alter plasma glucose levels in rats (52), suggesting that GnRH/LH release and blood glucose level might be independently regulated. Ritter and coworkers (53) suggested that blood glucose level and feeding behavior are independently regulated, because 4V injection of a GK inhibitor increased food intake but failed to affect the plasma glucose level. Further, injection of an immunotoxin into the PVN, which mainly resulted in a lesion of catecholaminegic neurons in the A1/A2 and C1 area, did not impair the hyperglycemic response to glucoprivation, despite its effectiveness in abolishing feeding (54). This fact indicated that these glucoprivic responses are mediated by different subpopulations of catecholamine neurons (54). Indeed, we previously suggested that the catecholaminergic neurons, originating in the medulla oblongata and projecting to the PVN, mediate LH suppression and increase feeding induced by glucoprivation (13, 55). Therefore, LH release and plasma glucose are independently regulated by energy status through hindbrain AMPK activity in different glucose sensing and/or neuronal pathways mediating glucoprivic responses.

In conclusion, the current study demonstrates that the AMPK-expressing ependymocyte located in the lower brainstem functions as an energy-sensing cell to control reproduction. We also strongly suggest that AMPK-expressing ependymal cilia can function as a sensory organelle to detect changes in nutritional cues in the CSF.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Hormone and Peptide Program and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. We also thank Dr A. F. Parlow for providing the LH assay kit and to Dr G. R. Merriam and Dr K. W. Wachter for the PULSAR computer program. The LH pulse analyses and RIA were performed at Nagoya University Information Technology Center and Nagoya University Radioisotope Center, respectively. We also thank Kayo Matsumoto, Tsubasa Haruta, and Mayumi Hayashi (Nagoya University) for their technical support.

This work was supported in part by the Research Program on Innovative Technologies for Animal Breeding, Reproduction, and Vaccine Development Grant REP2002 (to H.T.); by the Science and Technology Research Promotion Program for Agriculture, Forestry, Fisheries, and Food Industry of Japan (to H.T.); by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research 23380163 (to H.T.), 23580402 (to Y.U.), and 24380157 (to K.-i.M.); and by a Grant-in-Aid for Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Fellows 80003104 (to S.M.) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology. K.-i.M. received support from the Cooperative Study Program of the National Institute for Physiological Sciences Japan.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AICAR

- 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside, an AMPK activator

- AMPK

- AMP-activated protein kinase

- [Ca2+]i

- intracellular calcium concentration

- CC

- central canal

- CNS

- central nervous system

- CSF

- cerebrospinal fluid

- E2

- estradiol-17β

- GK

- glucokinase

- HKRB

- HEPES-buffered Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer

- ir

- immunoreactivity

- NTS

- nucleus tractus solitaries

- OVX

- ovariectomized

- P-AMPKα

- phospho-AMPKα

- PB

- phosphate buffer

- PVN

- paraventricular nucleus

- 4V

- 4th cerebroventricle

- Vim

- vimentin.

References

- 1. Wade GN, Schneider JE. Metabolic fuels and reproduction in female mammals. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1992;16(2):235–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Imakawa K, Day ML, Zalesky DD, Clutter A, Kittok RJ, Kinder JE. Effects of 17 β-estradiol and diets varying in energy on secretion of luteinizing hormone in beef heifers. J Anim Sci. 1987;64(3):805–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Foster DL, Olster DH. Effect of restricted nutrition on puberty in the lamb: patterns of tonic luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion and competency of the LH surge system. Endocrinology. 1985;116(1):375–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Matsuyama S, Ohkura S, Ichimaru T, et al. Simultaneous observation of the GnRH pulse generator activity and plasma concentrations of metabolites and insulin during fasting and subsequent refeeding periods in Shiba goats. J Reprod Dev. 2004;50(6):697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cagampang FR, Maeda K, Yokoyama A, Ota K. Effect of food deprivation on the pulsatile LH release in the cycling and ovariectomized female rat. Horm Metab Res. 1990;22(5):269–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Minabe S, Uenoyama Y, Tsukamura H, Maeda K. Analysis of pulsatile and surge-like luteinizing hormone secretion with frequent blood sampling in female mice. J Reprod Dev. 2011;57(5):660–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schreihofer DA, Amico JA, Cameron JL. Reversal of fasting-induced suppression of luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion in male rhesus monkeys by intragastric nutrient infusion: evidence for rapid stimulation of LH by nutritional signals. Endocrinology. 1993;132(5):1890–1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Oomura Y, Kimura K, Ooyama H, Maeno T, Iki M, Kuniyoshi M. Reciprocal activities of the ventromedial and lateral hypothalamic areas of cats. Science. 1964;143(3605):484–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oomura Y, Ono T, Ooyama H, Wayner MJ. Glucose and osmosensitive neurones of the rat hypothalamus. Nature. 1969;222(5190):282–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Levin BE, Dunn-Meynell AA, Routh VH. Brain glucose sensing and body energy homeostasis: role in obesity and diabetes. Am J Physiol. 1999;276(5 pt 2):R1223–R1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ritter RC, Slusser PG, Stone S. Glucoreceptors controlling feeding and blood glucose: location in the hindbrain. Science. 1981;213(4506):451–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Murahashi K, Bucholtz DC, Nagatani S, et al. Suppression of luteinizing hormone pulses by restriction of glucose availability is mediated by sensors in the brain stem. Endocrinology. 1996;137(4):1171–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kinoshita M, Moriyama R, Tsukamura H, Maeda KI. A rat model for the energetic regulation of gonadotropin secretion: role of the glucose-sensing mechanism in the brain. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2003;25(1):109–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Deane R, Segal MB. The transport of sugars across the perfused choroid plexus of the sheep. J Physiol. 1985;362:245–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Steffens AB, Scheurink AJ, Porte D, Jr, Woods SC. Penetration of peripheral glucose and insulin into cerebrospinal fluid in rats. Am J Physiol. 1988;255(2 pt 2):R200–R204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Spector R. Nutrient transport systems in brain: 40 years of progress. J Neurochem. 2009;111(2):315–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Iwata K, Kinoshita M, Yamada S, et al. Involvement of brain ketone bodies and the noradrenergic pathway in diabetic hyperphagia in rats. J Physiol Sci. 2011;61(2):103–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Maekawa F, Toyoda Y, Torii N, et al. Localization of glucokinase-like immunoreactivity in the rat lower brain stem: for possible location of brain glucose-sensing mechanisms. Endocrinology. 2000;141(1):375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. García M, Millán C, Balmaceda-Aguilera C, et al. Hypothalamic ependymal-glial cells express the glucose transporter GLUT2, a protein involved in glucose sensing. J Neurochem. 2003;86(3):709–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schuit FC, Huypens P, Heimberg H, Pipeleers DG. Glucose sensing in pancreatic β-cells: a model for the study of other glucose-regulated cells in gut, pancreas, and hypothalamus. Diabetes. 2001;50(1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moriyama R, Tsukamura H, Kinoshita M, Okazaki H, Kato Y, Maeda K. In vitro increase in intracellular calcium concentrations induced by low or high extracellular glucose levels in ependymocytes and serotonergic neurons of the rat lower brainstem. Endocrinology. 2004;145(5):2507–2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Iwata K, Kinoshita M, Susaki N, Uenoyama Y, Tsukamura H, Maeda K. Central injection of ketone body suppresses luteinizing hormone release via the catecholaminergic pathway in female rats. J Reprod Dev. 2011;57(3):379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Frayling C, Britton R, Dale N. ATP-mediated glucosensing by hypothalamic tanycytes. J Physiol. 2011;589(pt 9):2275–2286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Orellana JA, Sáez PJ, Cortés-Campos C, et al. Glucose increases intracellular free Ca(2+) in tanycytes via ATP released through connexin 43 hemichannels. Glia. 2012;60(1):53–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lage R, Diéguez C, Vidal-Puig A, López M. AMPK: a metabolic gauge regulating whole-body energy homeostasis. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14(12):539–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hardie DG, Scott JW, Pan DA, Hudson ER. Management of cellular energy by the AMP-activated protein kinase system. FEBS Lett. 2003;546(1):113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mountjoy PD, Bailey SJ, Rutter GA. Inhibition by glucose or leptin of hypothalamic neurons expressing neuropeptide Y requires changes in AMP-activated protein kinase activity. Diabetologia. 2007;50(1):168–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kohno D, Sone H, Minokoshi Y, Yada T. Ghrelin raises [Ca2+]i via AMPK in hypothalamic arcuate nucleus NPY neurons. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;366(2):388–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. López M, Lage R, Saha AK, et al. Hypothalamic fatty acid metabolism mediates the orexigenic action of ghrelin. Cell Metab. 2008;7(5):389–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lee K, Li B, Xi X, Suh Y, Martin RJ. Role of neuronal energy status in the regulation of adenosine 5′-monophosphate-activated protein kinase, orexigenic neuropeptides expression, and feeding behavior. Endocrinology. 2005;146(1):3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Minokoshi Y, Alquier T, Furukawa N, et al. AMP-kinase regulates food intake by responding to hormonal and nutrient signals in the hypothalamus. Nature. 2004;428(6982):569–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li AJ, Wang Q, Ritter S. Participation of hindbrain AMP-activated protein kinase in glucoprivic feeding. Diabetes. 2011;60(2):436–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Poyastro Pinheiro A, Thornton LM, Plotonicov KH, et al. Patterns of menstrual disturbance in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(5):424–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Butler WR. Nutritional interactions with reproductive performance in dairy cattle. Anim Reprod Sci. 2000;60–61:449–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cagampang FR, Maeda KI, Tsukamura H, Ohkura S, Ota K. Involvement of ovarian steroids and endogenous opioids in the fasting-induced suppression of pulsatile LH release in ovariectomized rats. J Endocrinol. 1991;129(3):321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nagatani S, Bucholtz DC, Murahashi K, et al. Reduction of glucose availability suppresses pulsatile luteinizing hormone release in female and male rats. Endocrinology. 1996;137(4):1166–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hayes MR, Skibicka KP, Bence KK, Grill HJ. Dorsal hindbrain 5′-adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase as an intracellular mediator of energy balance. Endocrinology. 2009;150(5):2175–2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nakamura N, Shida M, Hirayoshi K, Nagata K. Transcriptional regulation of the vimentin-encoding gene in mouse myeloid leukemia M1 cells. Gene. 1995;166(2):281–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Merriam GR, Wachter KW. Algorithms for the study of episodic hormone secretion. Am J Physiol. 1982;243(4):E310–E318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Maeda KI, Tsukamura H, Uchida E, Ohkura N, Ohkura S, Yokoyama A. Changes in the pulsatile secretion of LH after the removal of and subsequent resuckling by pups in ovariectomized lactating rats. J Endocrinol. 1989;121(2):277–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Xiao B, Heath R, Saiu P, et al. Structural basis for AMP binding to mammalian AMP-activated protein kinase. Nature. 2007;449(7161):496–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Millan C, Martinez F, Cortes-Campos C, et al. Glial glucokinase expression in adult and post-natal development of the hypothalamic region. ASN Neuro. 2010;2(3):e00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. da Silva Xavier G, Leclerc I, Varadi A, Tsuboi T, Moule SK, Rutter GA. Role for AMP-activated protein kinase in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and preproinsulin gene expression. Biochem J. 2003;371(pt 3):761–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mihaylova MM, Shaw RJ. The AMPK signalling pathway coordinates cell growth, autophagy and metabolism. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(9):1016–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cuyàs E, Corominas-Faja B, Joven J, Menendez JA. Cell cycle regulation by the nutrient-sensing mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1170:113–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kruger L, Maxwell DS. The fine structure of ependymal processes in the teleost optic tectum. Am J Anat. 1966;119(3):479–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yoshioka T, Tanaka O. Ultrastructural and cytochemical characterisation of the floor plate ependyma of the developing rat spinal cord. J Anat. 1989;165:87–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Del Bigio MR. Ependymal cells: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119(1):55–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Araque A, Carmignoto G, Haydon PG, Oliet SH, Robitaille R, Volterra A. Gliotransmitters travel in time and space. Neuron. 2014;81(4):728–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Oomura Y, Sasaki K, Suzuki K, et al. A new brain glucosensor and its physiological significance. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;55(1 suppl):278S–282S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Satir P, Christensen ST. Overview of structure and function of mammalian cilia. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:377–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kinoshita M, I'Anson H, Tsukamura H, Maeda K. Fourth ventricular alloxan injection suppresses pulsatile luteinizing hormone release in female rats. J Reprod Dev. 2004;50(3):279–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Li AJ, Wang Q, Dinh TT, Powers BR, Ritter S. Stimulation of feeding by three different glucose-sensing mechanisms requires hindbrain catecholamine neurons. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2014;306(4):R257–R264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ritter S, Bugarith K, Dinh TT. Immunotoxic destruction of distinct catecholamine subgroups produces selective impairment of glucoregulatory responses and neuronal activation. J Comp Neurol. 2001;432(2):197–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. I'Anson H, Sundling LA, Roland SM, Ritter S. Immunotoxic destruction of distinct catecholaminergic neuron populations disrupts the reproductive response to glucoprivation in female rats. Endocrinology. 2003;144(10):4325–4331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]