Abstract

Donohue syndrome (DS) is characterized by severe insulin resistance due to mutations in the insulin receptor (INSR) gene. To identify molecular defects contributing to metabolic dysregulation in DS in the undifferentiated state, we generated mesenchymal progenitor cells (MPCs) from induced pluripotent stem cells derived from a 4-week-old female with DS and a healthy newborn male (control). INSR mRNA and protein were significantly reduced in DS MPC (for β-subunit, 64% and 89% reduction, respectively, P < .05), but IGF1R mRNA and protein did not differ vs control. Insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of INSR or the downstream substrates insulin receptor substrate 1 and protein kinase B did not differ, but ERK phosphorylation tended to be reduced in DS (32% decrease, P = .07). By contrast, IGF-1 and insulin-stimulated insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) receptor phosphorylation were increased in DS (IGF-1, 8.5- vs 4.5-fold increase; INS, 11- vs 6-fold; P < .05). DS MPC tended to have higher oxygen consumption in both the basal state (87% higher, P =.09) and in response to the uncoupler carbonyl cyanide-p-triflouromethoxyphenylhydrazone (2-fold increase, P =.06). Although mitochondrial DNA or mass did not differ, oxidative phosphorylation protein complexes III and V were increased in DS (by 37% and 6%, respectively; P < .05). Extracellular acidification also tended to increase in DS (91% increase, P = .07), with parallel significant increases in lactate secretion (34% higher at 4 h, P < .05). In summary, DS MPC maintain signaling downstream of the INSR, suggesting that IGF-1R signaling may partly compensate for INSR mutations. However, alterations in receptor expression and pathway-specific defects in insulin signaling, even in undifferentiated cells, can alter cellular oxidative metabolism, potentially via transcriptional mechanisms.

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is a major public health problem worldwide. Intimately linked with the rise in diabetes prevalence is the burgeoning epidemic of obesity (1). Unfortunately, these alarming patterns are also increasingly observed in children and will likely translate into increases in cardiovascular and other health risks associated with insulin resistance and diabetes. The underlying molecular defects that confer diabetes risk remain unknown. Longitudinal studies in high-risk individuals indicate that insulin resistance is a very early marker of diabetes risk and also predicts the development of T2D (2, 3). Therefore, elucidating mechanisms by which cellular insulin resistance is linked to T2D is an essential step to develop new approaches for prevention and treatment.

Inherited syndromes of insulin resistance, although rare, have provided useful insights into insulin signaling and mechanisms of genetically determined insulin resistance (4–7). One example is Donohue syndrome (DS) (previously known as leprechaunism), a syndrome of severe insulin resistance caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in the insulin receptor (INSR) gene and accompanied by selective postreceptor defects (8–14). Clinically, this syndrome also includes growth retardation, decreased sc adipose tissue, acanthosis nigricans, ovarian enlargement with hyperandrogenism, fasting hypoglycemia, and early death (15–17).

We hypothesized that severe insulin resistance results in not only defects in insulin action but also in dysregulation of cellular metabolism. To approach this question, we generated mesenchymal progenitor cells (MPCs) from a DS patient with severe insulin resistance due to an INSR mutation, and analyzed these cells in comparison with cells derived from a healthy control child. Such MPCs are relatively undifferentiated but are no longer pluripotent and are committed toward mesodermal lineages (18). We demonstrate that severe, genetically defined insulin resistance, even in the absence of differentiation, alters cellular metabolism.

Materials and Methods

Fibroblast donors and sequence analysis

Dermal fibroblasts were obtained from the foreskin of a healthy newborn male (control; American Type Culture Collection Cell Repository Line-2522) and from a skin biopsy of a 1-month-old female with severe insulin resistance and DS (Coriell Cell Repository, Genetically modified 05241) due to a known nonsense mutation (A897X) in exon 14 of the INSR and an accompanying cis-acting mutation inherited from the mother, which together reduce INSR mRNA and cell-surface protein expression (2, 8, 9, 19). This patient was previously termed Minn1. Clinically, this patient was a small for gestational age Caucasian female with multiple phenotypic abnormalities (hirsutism, depressed nasal bridge, lack of sc fat) and severe insulin resistance (2). DNA sequence analysis of the INSR gene confirmed the A897X mutation, as well as normal sequence in the healthy control. In brief, genomic DNA was isolated from fibroblasts and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS) cells (DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit; QIAGEN). INSR exons were PCR amplified using specific primers (18) and GoTaq PCR Core Systems 1 (Promega) and sequenced using dye-labeled dideoxy terminators on ABI 3730 (Life Technologies).

iPS and MPC generation and culture

iPS cells were generated from skin fibroblasts using retroviral infection with octamer binding transcription factor 4 (OCT4), SRY (sex determining region Y) box 2 (SOX2), kruppel-like factor 4 (KLF4), and cellular myelocytomatosis oncogene (c-Myc) (Harvard Stem Cell Institute) (20). To generate MPCs, we first prepared embryoid bodies from iPS cells. iPS cells were treated with Dispase (BD Biosciences) and disaggregated into small clumps containing 5–10 cells, transferred to low-adhesion plastic 6-well dishes (Costar Ultra Low Attachment; Corning Life Sciences), and cultured in suspension in DMEM with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 1% Glutamax (all from Life Technologies). After 5–7 days, embryoid bodies were lifted and replated on gelatin-coated 6-well dishes in medium containing DMEM with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 1% Glutamax. After cells reached confluency (≈5 d), cells were harvested with trypsin (0.25%) and replated in medium containing DMEM, 15% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1% Glutamax, and 2.5-ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (Life Technologies). Medium was changed every other day. Cells were split at 70%–80% confluency. Morphology of MPC was assessed using phase contrast microscopy.

Cell viability

Cell viability was analyzed with Trypan blue exclusion, and cell size determined using an automated cell counter (Cellometer VISION, Nexcelom Bioscience).

Flow cytometry

To confirm mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) lineage, we used flow cytometry to assess expression of cell surface markers representative of MSC fate, including CD73, CD105, and CD90, and to confirm lack of expression of the hematopoietic antigens CD34 and CD45 (18). Cells were treated with trypsin, washed with PBS and centrifuged at 1000g for 5 minutes. 1 × 106 cells were transferred into polypropylene tubes, resuspended in PBS/5% FBS, and incubated with antibodies targeting CD73 (brilliant violet 421; BD Pharmingen), CD105 (R-phycoerythrin; Endoglin), CD90 (allophycocyanin; BD Pharmingen), CD34 (tandem conjugate of peridinin chlorophyll protein with Cy5.5 dye; BD Pharmingen), and CD45 (tandem conjugate of peridinin chlorophyll protein with Cy5.5 dye; BD Pharmingen) (final volume 100 μL). We determined the percentage of CD34−/CD45− cells expressing the MSC markers CD73, CD90, and CD105. Ten thousand events per cell type were acquired on a BD fluorescence-activated cell sorting Aria flow cytometer. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Treestar).

Insulin and IGF-1 signaling

Confluent MPCs were serum starved for 4 hours and treated with insulin or IGF-1 (0nM–100nM) for 1–10 minutes. Cells were lysed using 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate in PBS, and protein concentration was measured using bicinchoninic acid assay. Proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. Blots were incubated with primary antibodies, including anti-INSRβ (sc-711; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc), IGF-1R (sc-713; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc), phospho-IGF-1Rβ (Tyr1135/1136)/INSRβ (Tyr1150/1151) (3024; Cell Signaling), phospho-IRS-1 (pY612) (44816G; Life Technologies), total IRS-1 (2382; Cell Signaling), phospho-AKT Ser473 (9271; Cell Signaling), total AKT (9272; Cell Signaling), phospho-p44/42 MAPK (ERK1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204) (910; Cell Signaling), total ERK (9107; Cell Signaling), and β-actin (A9044; Sigma). After washing, bands were visualized using HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and ECL substrate (Thermo Scientific). Insulin and IGF-1 receptor phosphorylation was assessed independently using immunoprecipitation with anti-INSRβ (sc-711; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc) and anti-IGF-1R antibodies (sc-713; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc), and immunoblotting with antiphosphotyrosine antibodies (4G10; Millipore). MPCs were stimulated with insulin (1nM, 10nM, and 100nM) and IGF-1 (1nM and 10nM) for 5 minutes. HepG2 lysate (stimulated with 100nM insulin, 5 min) was used as control.

Analysis of cellular metabolism

Equal numbers of cells were seeded in gelatin-coated extracellular flux analyzer microplates (Seahorse Bioscience) and incubated with krebs ringer buffer (110nM NaCl, 4.7nM KCl, 2mM MgSO4, 1.2mM Na2HPO4, 0.24mM MgCl2, and 5mM glucose) for 1 hour before measurement of oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) using the XF24 Flux Analyzer (Seahorse Biosciences). Data were collected at baseline and at 5-minute intervals after sequential addition of the mitochondrial ATP synthase inhibitor oligomycin (10 μg/mL), the uncoupler FCCP (5μM), and the cytochrome C oxidase inhibitor KCN (50μM). OCR and ECAR values were normalized by DNA concentration.

To assess lactate secretion, 1 × 105 cells were plated per well in a 6-well plate, washed with PBS, and fresh krebs ringer buffer buffer with 5mM glucose was added. A total of 50 μL of media were removed at baseline and at 1, 2, and 4 hours for measurement of lactate concentration (K67–100; Biovision); values were normalized to cellular protein content (BCA).

Mitochondrial mass and potential

Mitochondrial mass and membrane potential were assessed by MitoTracker Green and MitoTracker Red CMXRos (Life Technologies) staining. Stock solutions (1mM) were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide and stored at −20°C. MPCs were stained in PBS with MitoTracker dyes (100nM) at 37°C for 10 minutes. After washing in ice cold PBS, MPCs were visualized using a fluorescent microscope (488 nm for MitoTracker Green, 594 nm for MitoTracker Red).

Mitochondrial DNA and protein content

Mitochondrial DNA content was assessed by PCR (Applied Biosystems 7900) using primers for ND1, ND4, and cyclooxygenase 2 (normalized to hemoglobin, beta). To isolate DNA, 50 μL of 50mM NaOH were added to each well, contents were boiled for 5 minutes at 95°C, and lysates were neutralized by addition of 5-μL 1M Tris (pH 6.8). To assess mitochondrial protein, cells were lysed using 1% SDS in PBS, and proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE for Western blotting, using antibodies recognizing citrate synthase (96600; Abcam), OXPHOS complexes (MitoProfile antibody cocktail, MS601; Mitosciences), and MDH2 (96193; Abcam).

Gene expression

RNA was isolated (RiboZol, AMRESCO) from cells harvested at 70%–80% confluency. cDNA was prepared by random hexamer priming (High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit; Life Technologies) before qRT-PCR (ABI 7900, primer sequences in Supplemental Table 1). All data were normalized to 36B4 and expressed relative to control.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using 2-tailed Student's t test. P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

We generated MPC from iPS cells derived from a healthy individual (control) and a patient with DS and severe insulin resistance due to INSR mutation. As seen in Supplemental Figure 1, MPCs have fibroblast-like morphology, with relatively large nucleus, and prominent nucleolus; this pattern did not differ between cells derived from DS vs control. However, viability was slightly reduced in DS (DS, 81 ± 2% vs CON, 87 ± 3%; P < .05) and cell size was increased (DS, 13.8 ± 0.99 μm vs CON, 12.5 ± 0.7 μm; P < .05).

To confirm that our MPC expressed markers typical of mesenchymal lineage (18), we analyzed cell surface markers by flow cytometry (n = 2) (Table 1). Both control and DS MPC cells expressed the mesenchymal markers CD73, CD90, and CD105 and lacked the hematopoietic surface antigens (CD34 and CD45), patterns which are consistent with mesenchymal lineage (18). Although fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis indicated a trend for lower expression of CD73 and CD105 in DS, there were no significant differences in expression of these antigens by PCR.

Table 1.

Antibody Table

| Peptide/Protein Target | Antigen Sequence (if known) | Name of Antibody | Manufacturer, Catalog Number, and/or Name of Individual Providing the Antibody | Species Raised in; Monoclonal or Polyclonal | Dilution Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brilliant Violet 421 antihuman CD73 | BD Biosciences, 562431 | Mouse; monoclonal | 5 μL per test (final volume 100 μL), 1 million cells | ||

| Allophycocyanin antihuman CD90 | BD Biosciences, 559869 | Mouse; monoclonal | 5 μL per test (final volume 100 μL), 1 million cells | ||

| R-phycoerythrin antihuman CD105 | BD Biosciences, 560839 | Mouse; monoclonal | 5 μL per test (final volume 100 μL), 1 million cells | ||

| PerCP-Cy5.5 antihuman CD34 | BD Biosciences, 347203 | Mouse; monoclonal | 20 μL per test (final volume 100 μL), 1 million cells | ||

| PerCP-Cy5.5 antihuman CD45 | BD Biosciences, 552724 | Mouse; monoclonal | 20 μL per test (final volume 100 μL), 1 million cells | ||

| Anti-INSRβ (C-19) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc, 711 | Rabbit; polyclonal | 1:200 | ||

| Anti-IGF-1R (C-20) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc, 713 | Rabbit; polyclonal | 1:200 | ||

| Phospho-IGF-1Rβ (Tyr1135/1136)/INSRβ (Tyr1150/1151) | Cell Signaling, 3024 | Rabbit; monoclonal | 1:1000 | ||

| Phosphospecific anti-IRS-1 (pY612) | Life Technologies, 44-816G | Rabbit; polyclonal | 1:1000 | ||

| IRS-1 | Cell Signaling, 2382 | Rabbit; polyclonal | 1:1000 | ||

| Phospho-Akt (Ser473) | Cell Signaling, 9271 | Rabbit; polyclonal | 1:1000 | ||

| Akt | Cell Signaling, 9272 | Rabbit; polyclonal | 1:1000 | ||

| Phospho-p44/42 MAPK (ERK1/2) | Cell Signaling, 9101 | Rabbit; polyclonal | 1:1000 | ||

| p44/42 MAPK (ERK1/2) | Cell Signaling, 9107 | Rabbit; polyclonal | 1:1000 | ||

| β-Actin | Sigma, A9044 | Mouse; monoclonal | 1:5000 | ||

| Antiphosphotyrosine | Millipore, 4G10 | Mouse; monoclonal | 1:500 |

INSR expression and signaling

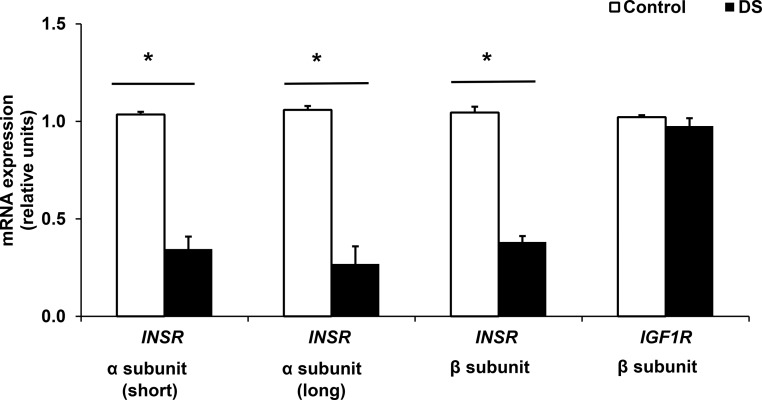

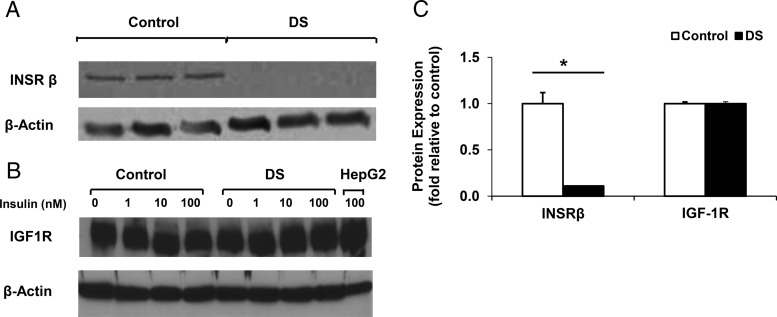

mRNA expression of the INSR α subunit (both short and long isoforms) and INSR β-subunit was reduced in DS cells as compared with control (67%, 75%, and 64% decrease, respectively, all P < .05; n = 3) (Figure 1). Similarly, INSR protein was reduced by 89% in DS (P < .05) (Figure 2). By contrast, expression of IGF-1R was similar at both mRNA and protein levels (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

mRNA expression of INSR is decreased in DS MPC, but IGF1R mRNA levels are similar. Values represent mRNA expression, as assessed by qRT-PCR; data are normalized to 36B4 and expressed relative to control. *, P < .05 for DS vs control, n = 3 experiments, each with 3 biological and 2 technical replicates.

Figure 2.

DS cells show reduction in INSR protein expression but similar IGF-1R protein levels. Representative Western blotting showing (A) INSRβ and (B) IGF-1R protein expression for control and DS MPCs; actin was used as a loading control. C, Quantification of protein level from 3 independent experiments (3 wells per cell line). *, P < .05 for comparison of DS with control.

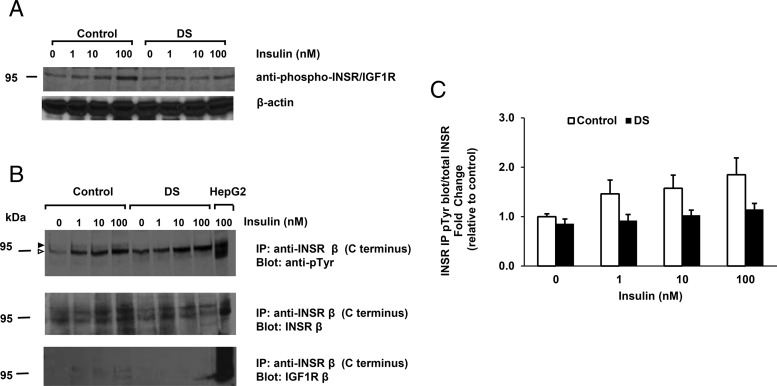

We next examined phosphorylation of the insulin and IGF-1 receptors. Because we did not observe a robust signal using an antibody which recognizes tyrosine phosphorylation of both the insulin and IGF-1 receptor, except at the 100nM insulin dose (Figure 3A), we assessed both insulin and IGF-1 receptor phosphorylation independently using immunoprecipitation with specific anti-INSR and anti-IGF-1R antibodies and immunoblotting with antiphosphotyrosine antibodies (for antibodies, please see Table 2). As expected, insulin stimulated phosphorylation of the INSR in control cells (1.8-fold increase at 100nM, P = .10). Insulin-stimulated INSR phosphorylation tended to be reduced in DS MPC (1.1-fold increase in DS vs 1.8-fold in control, P = .19) (Figure 3, B and C). We observed a doublet at 95 kDa, with upper band corresponding to the INSR (Figure 3B, indicated by black arrowhead) and a lower nonspecific band (open arrowhead). The upper band emerged in response to insulin in control cells, but not in DS cells (quantified in Figure 3C). By contrast, phosphorylation of IGF-1R in response to either insulin or IGF-1 was higher in DS (11- and 8.5-fold, respectively, vs 6- and 4.5-fold increase in control; P < .05 for both) (Supplemental Figure 2, A–D). Basal phosphorylation was also higher in DS MPC as compared with control MPC (1.4-fold increase in response to insulin vs 1.7-fold increase with IGF-1 stimulation, P > .05 for both) (Supplemental Figure 2, C and D).

Figure 3.

Insulin-stimulated INSR phosphorylation tends to be reduced in DS MPC. A, Western blotting using phosphospecific anti-INSR/IGF-1R antibody. B, Antiphosphotyrosine Western blotting of anti-INSR immunoprecipitate. Black and open arrowheads indicate INSR and nonspecific bands, respectively. C, Quantification from 2 independent experiments. MPCs were stimulated with insulin (1nM, 10nM, and 100nM) for 5 minutes. HepG2 lysate (stimulated with 100nM insulin, 5 min) was used as control.

Table 2.

Flow Cytometry Analysis of Cell Surface Marker Expression Pattern in Control vs DS MPC Is Consistent With MSC Lineage

| MSC Markers (% of CD34- and CD45-negative cells) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| CD73 | CD90 | CD105 | |

| Control MPC | 98.4 ± 0.4 | 99.0 ± 0.8 | 94.9 ± 0.1 |

| DS MPC | 74.8 ± 9.4 | 99.1 ± 1.0 | 88.1 ± 7.9 |

1 × 106 cells were analyzed for each cell line. Data indicate the percentage of CD34- and CD45-negative cells that were positive for the indicated MSC marker (mean ± SD), and represent the mean of 2 independent experiments.

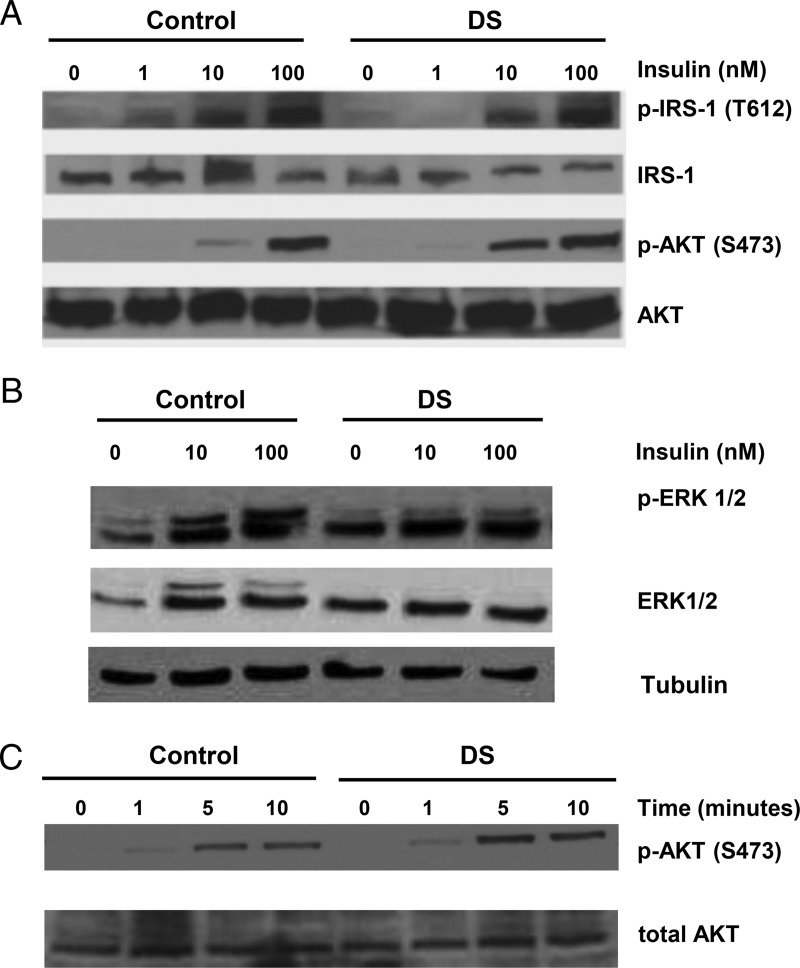

We next examined insulin signaling downstream of the insulin and IGF-1 receptors. DS MPC were responsive to insulin (100nM), as indicated by phosphorylation of IRS-1 and AKT (Figure 4A and Supplemental Figure 3). These patterns did not differ in amplitude from control MPC, and the time course of insulin-stimulated AKT phosphorylation was similar (Figure 4B). However, insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of ERK (both ERK1 and ERK2) tended to be reduced in DS MPC (32% reduction at 100nM, P = .07; n = 4) (Figure 4A and Supplemental Figure 3). We observed no differences in the mRNA expression of several insulin signaling proteins, including IRS-1, IRS-2, AKT1, ERK1, and FOXO1 (Supplemental Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Insulin-stimulated IRS-1 and AKT phosphorylation are preserved in DS MPC, but ERK1/2 phosphorylation is reduced. A, Representative Western blottings for IRS-1 and AKT phosphorylation. B, Representative Western blottings for ERK phosphorylation. C, Time course of AKT phosphorylation. Confluent MPCs were serum starved for 4 hours and treated with insulin for dose response (0nM–100nM insulin for 10 min) and time course (100nM insulin for 0, 1, 5, and 10 min) analysis. Quantification (from 4 independent experiments) for IRS-1, AKT, and ERK phosphorylation is shown in Supplemental Figure 2.

Cellular metabolism

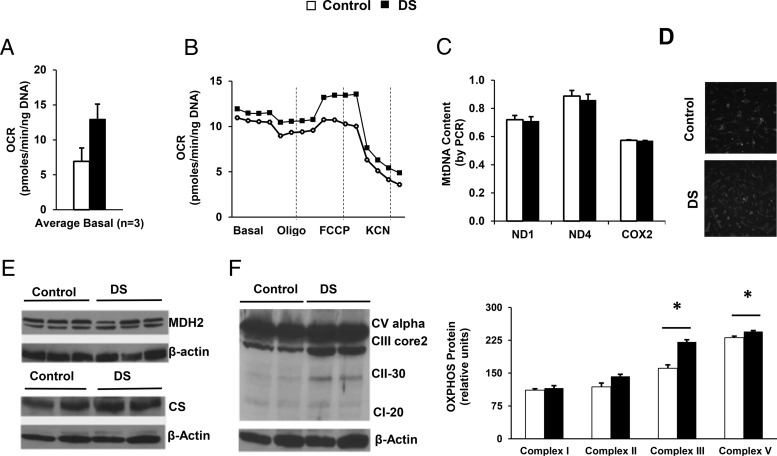

To determine whether genetically determined insulin resistance affected metabolism in MPC, we assessed cellular bioenergetics. As seen in Figure 5A, basal OCR tended to be higher in DS MPC (87% higher than control, P = .09, n = 3). Although responses to the ATP synthase inhibitor oligomycin were similar, response to the uncoupler FCCP tended to increase in DS (2-fold, P = .06, n = 3) (Figure 5B). Given that increased OCR in DS MPC could reflect increased mitochondrial mass, we assessed mitochondrial DNA content and staining. Neither mitochondrial DNA content, as assessed by PCR, or mitochondrial mass, as assessed by MitoTracker Green staining, differed between control and DS (Figure 5, C and D). Moreover, we observed no differences in mitochondrial membrane potential, as assessed by MitoTracker Red staining (Supplemental Figure 5). Although Western blotting revealed no changes in expression of the mitochondrial proteins MDH2 and citrate synthase (Figure 5E), expression of OXPHOS complexes III and V was increased in DS MPCs (37% and 6% increase, respectively; both P < .05) (Figure 5F).

Figure 5.

OCR is higher in DS MPC after treatment with the uncoupler FCCP, despite similar mitochondrial mass and mitochondrial DNA. A, Basal OCR in MPCs (average of 3 experiments). B, Representative bioenergetic profile of control and DS MPC, assessed at baseline and after sequential addition of oligomycin (10 μg/mL), FCCP (5μM), and KCN (50μM). OCR was analyzed at 5-minute intervals and normalized by DNA. C, Mitochondrial DNA content, determined using primers for ND1, ND4, and COX2, with nuclear HBB as control (duplicate assays of 3 wells per cell line). D, MitoTracker Green staining (100nM, incubated at 37°C for 10 min). E, Control and DS MPC have similar protein levels of MDH2 and citrate synthase, with actin as loading control (duplicate samples for each cell line). F, Western blotting of mitochondrial OXPHOS proteins, with quantification in right panel (n = 2 experiments, duplicate samples). *, P < .05 for DS vs control.

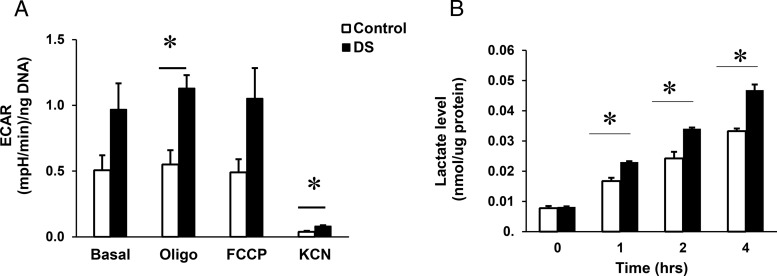

We next analyzed ECAR, a surrogate measure for glycolytic flux. As seen in Figure 6A, basal ECAR tended to be increased by 91% in DS MPC (P = .07). Because this suggested increased lactate production, we directly measured lactate in conditioned medium. Lactate levels were significantly higher in medium from DS MPC at all 3 time points during a 4-hour time course (34% higher than control at 4 h, P < .05, n = 1, 3 replicates) (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Extracellular acidification and lactate levels in conditioned medium are increased in DS MPC. A, Quantification of ECAR in control vs DS MPC (n = 3 experiments). ECAR was assessed at baseline and after sequential addition of oligomycin (10 μg/mL), FCCP (5μM), and KCN (50μM) and normalized by DNA concentration. B, Assay of lactate in conditioned medium. Lactate concentrations were measured in conditioned medium at baseline and 1, and 2 and 4 hours after glucose addition (n = 1 experiment, 3 wells for each time point) and normalized to cellular protein content. *, P < .05 for DS vs control.

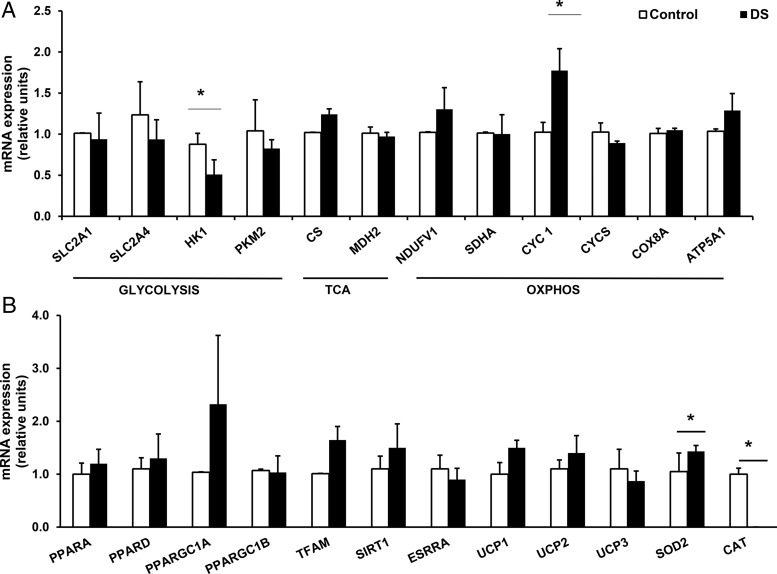

To assess potential transcriptional mechanisms contributing to differences in bioenergetics in DS vs control MPCs, we assessed expression of key metabolic regulatory genes using qRT-PCR (Figure 7, A and B). Notably, DS MPC showed significant down-regulation of hexokinase 1 (42% decrease, P = .02), with a similar trend for the SLC2A4 glucose transporter (24% lower, P = .09). mRNA expression of cytochrome C-1 was significantly increased in DS MPC (73% higher, P = .04). There were no significant differences in expression of nuclear-encoded genes regulating mitochondrial biogenesis; however, PPARGC1A and TFAM tended to be increased in DS MPC. DS MPC also showed significant alterations in antioxidant gene expression, with up-regulation of SOD2 (37% increase, P = .05) and a greater than 95% reduction in catalase expression vs control (P = .004).

Figure 7.

Expression of potential metabolic regulatory genes in control vs DS MPC, assessed by qRT-PCR. A, Expression of genes involved in glycolysis, TCA cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation (n = 3 experiments, duplicate analysis of 3 wells per condition). B, Expression of genes regulating mitochondrial biogenesis, uncoupling, and oxidative stress (n = 3 experiments, duplicate analysis of 3 wells per condition). All data normalized to 36B4 and expressed relative to control. *, P < .05 comparing DS with control by Student's t test.

Discussion

Both iPS cells and mesenchymal progenitors derived from them are relatively undifferentiated (21), and few epigenetic marks are retained during reprogramming (22). Thus, these cells permit dissection of the impact of genetic mutations on cellular function, largely independent of environmentally mediated and differentiation-dependent mechanisms. We have used MPC derived from a patient with DS to assess the impact of genetically determined insulin resistance on cellular signaling and metabolism.

We demonstrate that expression of the INSR, at both mRNA and protein levels, is reduced in MPC derived from a patient with DS. Previous publications describing fibroblasts from this patient (termed Minn1) have demonstrated more than 90% decrease in INSR mRNA and cell-surface protein (2, 5, 8, 17, 23). These results are similar to previous studies of cultured skin fibroblasts or transformed lymphocytes derived from patients with DS, which also showed markedly reduced INSR affinity and/or number (23–28). By contrast, IGF-1 receptor mRNA, protein, and binding are similar (29). Interestingly, despite the observed reduction in INSR content, phosphorylation of the INSR or proximal downstream signaling proteins was not significantly altered in DS MPC. Several possibilities may account for these findings. First, this DS patient had a heterozygous mutation resulting in residual wild-type INSR protein. As seen in the immunoprecipitation experiments, the anti-C-terminal antibody may have enriched for the small amount of nonmutated INSR protein. In addition, both insulin and IGF-1 stimulation of the IGF-1 receptor was higher in DS, suggesting that signaling by IGF-1 receptor and INSR/IGF-1R hybrids may provide at least partial compensation for reduced INSR expression.

Despite potential compensation by the IGF-1 receptor, DS MPC showed selective reductions in downstream insulin signaling. Although we observed no change in phosphorylation of IRS-1 or AKT-dependent signaling, insulin-stimulated ERK phosphorylation (both ERK1 and ERK2) was reduced in DS cells. Given that ERK-dependent pathways are critical for cellular growth (30), such reductions in ERK activation could contribute to the growth retardation observed clinically in patients with DS. Altered insulin signaling has also been observed in other cell models of DS, such as induced pluripotent stem cells and fibroblasts from which they were originally derived (31). However, differences in transcriptional profiles were also observed between iPSC and fibroblasts, suggesting cell type-specific regulation.

Our data indicating disturbances in downstream signaling and regulation of metabolism are broadly consistent with previous studies of fibroblasts derived from patients with DS, which reported substantial heterogeneity in INSR autophosphorylation or kinase activity in individual patients, paralleling the diversity of mutations (23–27). Reddy et al (8) demonstrated that INSR autophosphorylation and receptor-associated tyrosine kinase activity were reduced in Minn1 fibroblasts. By contrast, we observe that INSR tyrosine phosphorylation is preserved in MPC derived from the Minn1 patient but that ERK-dependent pathways are perturbed. Although these differences could reflect in part the methodology employed to analyze INSR signaling, it is likely that regulatory mechanisms that have a major impact on insulin signaling differ between fibroblasts and MPC, potentially due to differences in differentiation and/or epigenetic regulation. Additional studies evaluating the full spectrum of insulin signaling defects and their modulation during progression from pluripotency to differentiated state in multiple individuals with DS and across a spectrum of mutations will be required to address this important question.

DS MPCs also have alterations in cellular metabolism. Oxygen consumption tended to be increased in DS, in both the basal state and in response to the uncoupler FCCP. This is unlikely due to increased global mitochondrial mass, as we observed no alterations in mitochondrial DNA content, MitoTracker Green staining, or citrate synthase protein. Increased oxygen consumption could also reflect uncoupling. We observed no alterations in expression of the uncoupling proteins UCP1–UCP3 and found no differences in mitochondrial membrane potential, as assessed by MitoTracker Red staining. mRNA expression of cytochrome C-1 (heme-containing component of the cytochrome b-c1 complex, which accepts electrons from Rieske protein and transfers electrons to cytochrome C) was markedly increased, and in parallel, protein content of both OXPHOS complexes III and V was also significantly increased in DS MPC. Interestingly, expression of antioxidant response genes were also significantly altered in DS MPC, with marked suppression of catalase expression and up-regulation of superoxide dismutase 2. Dysregulation of antioxidant response pathways, as noted in DS fibroblasts (32, 33), could also contribute to uncoupling observed in DS MPC.

Given the importance of glycolytic pathways in stem cells for maintenance of energetic homeostasis (34), it is particularly interesting that extracellular acidification and lactate production are increased in DS cells, suggesting underlying cellular energetic stress. Whether this could be due to reductions in glucose uptake and metabolism associated with reduced hexokinase expression, or alterations in net ATP production due to dysregulation of OXPHOS complex function, will be assessed in future studies.

More broadly, our data provide important evidence addressing the relationship between insulin resistance and control of metabolic homeostasis. In recent years, abnormal mitochondrial metabolism has been linked to insulin resistance (35). For example, magnetic resonance spectroscopy has demonstrated decreased ATP synthesis in muscle from patients with T2D, with similar patterns in insulin resistant individuals with family history of diabetes (36). Similarly, analysis of muscle biopsies from insulin resistant subjects has demonstrated decreases in mRNA expression of both nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes and mitochondrial DNA, lower protein expression of respiratory chain subunits, and reduced mitochondrial size, density, and oxidative enzyme activities (36–40). In addition, interventions such as exercise and caloric restriction, which improve insulin sensitivity, also enhance mitochondrial function (41, 42). In mice, defects in insulin signaling can cause mitochondrial dysfunction (43).

In this context, studies in humans with INSR mutations can provide important insights into the relationship between insulin resistance and metabolism. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies in patients with milder forms of insulin resistance due to distinct INSR mutations have revealed reductions in muscle phosphocreatine resynthesis, indicating energetic stress (44). However, these in vivo relationships are difficult to unravel at a molecular level, and are made even more complex by the epigenetic changes that may result from chronic environmental exposures. Our studies in mesenchymal precursor cells derived from DS fibroblasts provide further support for the concept that primary, genetically determined insulin resistance can contribute to disordered regulation of cellular metabolism. Given that few epigenetic marks are retained during the reprogramming process, it is likely that observed differences between control and insulin resistant cells reflect genetically determined insulin resistance. We acknowledge that intrinsic differences in genetic background between individuals, clonal variation, or residual epigenetic differences that persist during the cellular reprogramming process could also contribute.

In summary, we demonstrate that MPCs derived from a patient with DS due to INSR mutation have alterations in expression of the INSR, pathway-specific defects in insulin signaling, and disturbances in cellular oxidative metabolism. In turn, these defects are likely mediated by INSR-dependent perturbations in transcriptional regulation of metabolic and mitochondrial protein complexes. Analysis of additional patient-derived lines will be required to define the specific molecular mechanisms which link INSR mutations and defective regulation of cellular metabolism. Our results may also help guide further studies of cells from individuals with less severe forms of insulin resistance associated with human prediabetes and T2D.

Acknowledgments

We thank Asma Ejaz and Laura Warren for technical assistance and Girijesh Buruzula and Joyce LaVecchio of the Joslin DRC Flow Cytometry Core for assistance with flow cytometry.

This work was supported in part by a Pediatric Endocrine Society grant (B.B.), the National Institutes of Health Grant T32DK007260 (to A.B.), the Harold Whitworth Pierce Charitable Trust postdoctoral fellowship (A.B.), The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (V.T.), the American Diabetes Association (M.-E.P.), and the Novo Foundation (M.-E.P. and C.R.K.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AKT

- protein kinase B

- CD

- cluster of differentiation

- DS

- Donohue syndrome

- ECAR

- extracellular acidification rate

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- FCCP

- carbonyl cyanide-p-triflouromethoxyphenylhydrazone

- IGF-1R

- insulin like growth factor 1 receptor

- INSR

- insulin receptor

- iPS

- induced pluripotent stem cells

- IRS-1

- insulin receptor substrate 1

- KCN

- potassium cyanide

- MDH2

- malate dehydrogenase 2

- Minn1

- Minnesota 1

- MPC

- mesenchymal progenitor cell

- MSC

- mesenchymal stem cell

- ND

- NADH dehydrogenase

- OCR

- oxygen consumption rate

- OXPHOS

- oxidative phosphorylation

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- T2D

- type 2 diabetes

- 36B4

- ribosomal protein 36B4.

References

- 1. Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1047–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Taylor SI. Lilly lecture: molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance. Lessons from patients with mutations in the insulin receptor gene. Diabetes. 1992;41:1473–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Martin BC, Warram JH, Krolewski AS, Bergman RN, Soeldner JS, Kahn CR. Role of glucose and insulin resistance in development of type 2 diabetes mellitus: results of a 25-year follow-up study. Lancet. 1992;340:925–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Longo N, Wang Y, Smith SA, Langley SD, DiMeglio LA, Giannella-Neto D. Genotype-phenotype correlation in inherited severe insulin resistance. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1465–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Podskalny JM, Kahn CR. Cell culture studies on patients with extreme insulin resistance. I. Receptor defects on cultured fibroblasts. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1982;54:919–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Donahue WL, Uchida I. Leprechaunism: a euphemism for a rare familial disorder. J Pediatr. 1954;45:505–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kosztolányi G. Leprechaunism/Donohue syndrome/insulin receptor gene mutations: a syndrome delineation story from clinicopathological description to molecular understanding. Eur J Pediatr. 1997;156:253–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reddy SS, Lauris V, Kahn CR. Insulin receptor function in fibroblasts from patients with leprechaunism. Differential alterations in binding, autophosphorylation, kinase activity, and receptor-mediated internalization. J Clin Invest. 1988;82:1359–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reddy SS, Kahn CR. Epidermal growth factor receptor defects in leprechaunism. A multiple growth factor-resistant syndrome. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1569–1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. al-Gazali LI, Khalil M, Devadas K. A syndrome of insulin resistance resembling leprechaunism in five sibs of consanguineous parents. J Med Genet. 1993;30:470–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Der Kaloustian VM, Kronfol NM, Takla R, Habash A, Khazin A, Najjar SS. Leprechaunism. A report of two new cases. Am J Dis Child. 1971;122:442–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Desbois-Mouthon C, Girodon E, Ghanem N, et al. Molecular analysis of the insulin receptor gene for prenatal diagnosis of leprechaunism in two families. Prenat Diagn. 1997;17:657–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hone J, Accili D, Psiachou H, et al. Homozygosity for a null allele of the insulin receptor gene in a patient with leprechaunism. Hum Mutat. 1995;6:17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Suliman SG, Stanik J, McCulloch LJ, et al. Severe insulin resistance and intrauterine growth deficiency associated with haploinsufficiency for INSR and CHN2: new insights into synergistic pathways involved in growth and metabolism. Diabetes. 2009;58:2954–2961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Elders MJ, Schedewie HK, Olefsky J, et al. Endocrine-metabolic relationships in patients with leprechaunism. J Natl Med Assoc. 1982;74:1195–1210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ioan D, Dumitriu L, Belengeanu V, Bistriceanu M, Maximilian C. Leprechaunism: report of two cases and review. Endocrinologie. 1988;26:205–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Elsas LJ, Endo F, Strumlauf E, Elders J, Priest JH. Leprechaunism: an inherited defect in a high-affinity insulin receptor. Am J Hum Genet. 1985;37:73–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:315–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Muller-Wieland D, Taub R, Tewari DS, et al. Insulin-receptor gene and its expression in patients with insulin resistance. Diabetes. 1989;38:31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tuthill A, Semple RK, Day R, et al. Functional characterization of a novel insulin receptor mutation contributing to Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2007;66:21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ahfeldt T, Schinzel RT, Lee YK, et al. Programming human pluripotent stem cells into white and brown adipocytes. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:209–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kim K, Doi A, Wen B, et al. Epigenetic memory in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2010;467:285–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kadowaki T, Kadowaki H, Rechler MM, et al. Five mutant alleles of the insulin receptor gene in patients with genetic forms of insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:254–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kaplowitz PB, D'Ercole AJ. Fibroblasts from a patient with leprechaunism are resistant to insulin, epidermal growth factor, and somatomedin C. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1982;55:741–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kadowaki T, Bevins CL, Cama A, et al. Two mutant alleles of the insulin receptor gene in a patient with extreme insulin resistance. Science. 1988;240:787–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shimada F, Taira M, Suzuki Y, et al. Insulin-resistant diabetes associated with partial deletion of insulin-receptor gene. Lancet. 1990;335:1179–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kadowaki T, Kadowaki H, Accili D, Yazaki Y, Taylor SI. Substitution of arginine for histidine at position 209 in the α-subunit of the human insulin receptor. A mutation that impairs receptor dimerization and transport of receptors to the cell surface. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:21224–21231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ojamaa K, Hedo JA, Roberts CT, Jr, et al. Defects in human insulin receptor gene expression. Mol Endocrinol. 1988;2:242–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Goodman PA, Sbraccia P, Brunetti A, et al. Growth factor receptor regulation in the Minn-1 leprechaun: defects in both insulin receptor and epidermal growth factor receptor gene expression. Metabolism. 1992;41:504–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McCubrey JA, Steelman LS, Chappell WH, et al. Roles of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway in cell growth, malignant transformation and drug resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:1263–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Iovino S, Burkart AM, Kriauciunas K, et al. Genetic insulin resistance is a potent regulator of gene expression and proliferation in human iPS cells. Diabetes. 2014;63:4130–4142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Park HS, Jin DK, Shin SM, et al. Impaired generation of reactive oxygen species in leprechaunism through downregulation of Nox4. Diabetes. 2005;54:3175–3181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Melis R, Pruett PB, Wang Y, Longo N. Gene expression in human cells with mutant insulin receptors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;307:1013–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rafalski VA, Mancini E, Brunet A. Energy metabolism and energy-sensing pathways in mammalian embryonic and adult stem cell fate. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:5597–5608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lowell BB, Shulman GI. Mitochondrial dysfunction and type 2 diabetes. Science. 2005;307:384–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Petersen KF, Dufour S, Befroy D, Garcia R, Shulman GI. Impaired mitochondrial activity in the insulin-resistant offspring of patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:664–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kelley DE, Goodpaster B, Wing RR, Simoneau JA. Skeletal muscle fatty acid metabolism in association with insulin resistance, obesity, and weight loss. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:E1130–E1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kelley DE, He J, Menshikova EV, Ritov VB. Dysfunction of mitochondria in human skeletal muscle in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:2944–2950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Heilbronn LK, Gan SK, Turner N, Campbell LV, Chisholm DJ. Markers of mitochondrial biogenesis and metabolism are lower in overweight and obese insulin-resistant subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:1467–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Skov V, Glintborg D, Knudsen S, et al. Reduced expression of nuclear-encoded genes involved in mitochondrial oxidative metabolism in skeletal muscle of insulin-resistant women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes. 2007;56:2349–2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Østergård T, Andersen JL, Nyholm B, et al. Impact of exercise training on insulin sensitivity, physical fitness, and muscle oxidative capacity in first-degree relatives of type 2 diabetic patients. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290:E998–E1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Toledo FG, Menshikova EV, Ritov VB, et al. Effects of physical activity and weight loss on skeletal muscle mitochondria and relationship to glucose control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes. 2007;56:2142–2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Taira M, Taira M, Hashimoto N, et al. Human diabetes associated with a deletion of the tyrosine kinase domain of the insulin receptor. Science. 1989;245:63–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sleigh A, Raymond-Barker P, Thackray K, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in patients with primary congenital insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2457–2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]