Abstract

The structure of the Eysenck Personality Inventory (EPI) is poorly understood, and applications have mostly been confined to the broad Neuroticism, Extraversion, and Lie scales. Using a hierarchical factoring procedure, we mapped the sequential differentiation of EPI scales from broad, molar factors to more specific, molecular factors, in a UK population sample of over 6500 persons. Replicable facets at the lowest tier of Neuroticism included emotional fragility, mood lability, nervous tension, and rumination. The lowest order set of replicable Extraversion facets consisted of social dynamism, sociotropy, decisiveness, jocularity, social information seeking, and impulsivity. The Lie scale consisted of an interpersonal virtue and a behavioral diligence facet. Users of the EPI may be well served in some circumstances by considering its broad Neuroticism, Extraversion, and Lie scales as multifactorial, a feature that was explicitly incorporated into subsequent Eysenck inventories and is consistent with other hierarchical trait structures.

1. Introduction

The Eysenck Personality Inventory (EPI) was developed to measure the personality dimensions of Extraversion and Neuroticism (S. B. G. Eysenck, & Eysenck, H.J., 1964). Although the EPI has given way to the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire, (EPQ) (H. J. Eysenck, & Eysenck, S.B.G., 1975) and Eysenck Personality Profiler (EPP) (H. J. Eysenck, & Wilson, G.D., 1991), the factor structure of the EPI remains of interest for two reasons. The first is historical: it illuminates the lineage of the newer Eysenck inventories, informing how and why they evolved. The second reason is of considerably greater practical importance: The EPI continues to be used in several studies worldwide.

1.1 Theoretical and Historical Considerations

The sequence of Eysenck inventories began with the Maudsley Medical Questionnaire (H. J. Eysenck, 1952) and its revision, the Maudsley Personality Inventory (H. J. Eysenck, 1959). These instruments operationalized Eysenck's early concepts of Neuroticism and Extraversion, which he considered dimensions of temperament (H. J. Eysenck, 1947, 1952). The Maudsley inventories gave rise to the EPI, and maintained the same number and format of items, as well as a Lie scale. Although Neuroticism and Extraversion subsumed more specific traits, Eysenckian theory in the era of the EPI's inception focused less on subcomponents of Neuroticism and Extraversion and more on the circumplex created by these two conceptually orthogonal dimensions. This yielded a plane with quadrants representing the classical Greek phlegmatic, sanguine, choleric, and melancholic personality types (H. J. Eysenck, 1947, 1952). The EPQ added Psychoticism (H. J. Eysenck, & Eysenck, S.B.G., 1976) and replaced or eliminated many EPI items, reducing the length from 57 to 48 items (H. J. Eysenck, & Eysenck, S.B.G., 1975). This alteration provided a more elaborated factor structure, moving impulsivity content away from Extraversion on the EPI and onto the EPQ's Psychoticism scale. Later, the EPQ-R was expanded to 100 items (S. B. G. Eysenck, Eysenck, H.J., and Barrett, P., 1985).

However, as early as 1975, Eysenck published an initial version of the EPP (Eysenck Barrett, Wilson & Jackson, 1992), which was specifically hierarchical with seven subcomponents beneath each of the 3 domains (H. J. Eysenck, & Wilson, G.D., 1991), as well as abbreviated EPP versions with 6, 12, or 20 items per subscale (Francis & Jackson, 2004). Thus, the EPI itself marks a transition point in the fossil record of Eysenck's inventories from a broad, 2-dimensional circumplex conceptualization to a more differentiated and hierarchically organized trait structure. Perhaps because of this, studies of the EPI have tended to report rather widely varying factor structures corresponding to a single tier, rather than s hierarchical structure.

1.2 Practical Importance

The EPI's factor structure is not strictly a historical curiosity, since the EPI continues to be used in personality research. A PsycInfo search using the term “Eysenck Personality Inventory” reveals a large number of recent papers reporting its use: 29 in the first 8 months of 2011, 66 in 2010, and 97 in 2009, including several large, on-going cohort studies (e.g., the Health and Lifestyle Survey (HALS) (Shipley, Weiss, Der, Taylor, & Deary, 2007). Delineating its hierarchical structure is thus critical for three practical reasons.

First, when an outcome is association with Neuroticism or Extraversion, the most basic scientific question is “what is it about people higher in Neuroticism/Extraversion that causes them to experience outcome X?” The answer to this question is seldom apparent because the broad trait is composed of heterogeneous content. A particularly vexing problem occurs when different narrow traits located under the same general factor predict an outcome in opposite directions, leading to null associations when these effects are average at the broad factor level. Facet analyses can clarify exactly what elements of the broad scale are driving the associations, and in which directions.

Second, there is often a practical interest in prediction in personality research: How much outcome variance can be accounted for by dimensions of dispositional variation? In some cases, particularly when outcomes are “broad-band”, multifactorial or “molar” composites, broad personality dimensions may be good predictors. However, in other cases, the collection of facets comprising the broad personality scale may collectively predict more outcome variance than the broad scale itself. Pure prediction power is important in settings such as industrial psychology, where one wishes to identify candidates likely to be successful in a particular job, or health psychology, where predicting future health problem is critical for targeted prevention.

Third, it is often difficult to interpret findings for similarly named scales because the degree of construct similarity vs. construct equivalence is unknown (Barrett & Rolland, 2009). Direct comparison of construct-equivalent scales is sensible, while comparison of only semantically-similar scales must be done with a careful attention to variation in content and theory. A scale's facet structure represents a critical window on its content and, usually, the personality theory underlying the scale. For instance, both the EPI and numerous Big Five inventories contain Neuroticism and Extraversion scales. However, the facet configurations of each scale may reflect somewhat varying theories of these broad personality domains, despite semantic similarity of the broad scale names. Convergent correlation between two different measures of the broad trait is somewhat helpful, but is often not available in the study, can be misleading if adduced from dissimilar samples, and does pinpoint content clusters leading to divergence. However, it is always possible to examine the clustering of content reflected in a facet structure, and compare this to as many other instruments as one wishes, in the context of the underlying theory of each.

For these reasons, we set out to map the hierarchical structure of the EPI in the Health. and Lifestyle Survey (Blaxter, 1987), a large UK population cohort. We examined the hierarchical structure of the EPI Neuroticism and Extraversion domains, as well as the “Lie” scale. Evidence has mounted that “lie” scales are likely to be measures of real inter-individual differences in behavior and perception, rather than measures of dissembling or response bias (Griffith & Peterson, 2008). For instance, some have argued that social desirability scales measure a trait capturing general adaptation to life (McCrae & Costa, 1983), which may be multifaceted. Therefore, we also examined the “lie” scale, conceptualizing it as an item set tapping responsibility and prosocial behavior. We used a top-down approach known as “bass-ackward” factoring (Goldberg, 2006). This involves creating a hierarchy of increasing scale differentiation by beginning with single factor solution at the top, and moving downward with a series of factor analyses to identify successively more differentiated tiers of facets. The goal was to develop a factor tree, mapping the branching of EPI content domains from broad or molar, to more specific or molecular traits.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants and Procedure

The HALS was designed to examine behavioral factors associated with health outcomes in non-institutionalized adults 18 and over living in England, Scotland, or Wales (see (Blaxter, 1987). It consisted of an initial baseline interview by a visiting nurse about numerous lifestyle issues, conducted in 1984-1985. During this interview, nurses introduced the EPI and left it with subjects, who completed it with standard instructions and returned it by mail. Of the 9002 interviewed persons, 6550 returned usable personality data. Older persons were slightly less likely to return the EPI than younger persons (odds ratio for 1 year of age = .94, or 6% less likely to return; p < .001), with no differences noted for gender. The resulting sample was 55.6 % female, with a mean age of 45.3 (SD = 17.1).

2.2 Measures

The EPI (S. B. Eysenck, & Eysenck, H.J., 1964) is a 57 item true-false self-report personality measure assessing Neuroticism (24 items) and Extraversion (24 items). It also includes a Lie scale (9 items). Nine items were negatively keyed on the Extraversion scale, six on the “Lie” scale, and none on the Neuroticism scale. In preliminary analyses, differing numbers of extracted factors contained mixtures of both positively and negatively keyed items, suggesting that a keying, directional, or acquiescence method factor was not strongly operant (Marsh, 1996). Preliminary analyses showed some degree of correlation between the broad scales, although they did not strongly define a general personality factor (i.e., loadings < .4) when a single factor was extracted from their correlation matrix.

2.3 Analyses

To prepare items for analyses, we recoded them so that they reflected higher levels of Neuroticism, Extraversion, or “lying”. Then, for participants with at least two-thirds of the items on a scale, we imputed the modal response for missing items. 6108 persons completed all extraversion items, with an additional, 457 completing at least 2/3rds but less than all; 6124 persons completed all neuroticism items, with an additional 418 completing at least 2/3rds but less than all; and 6374 persons completed all “Lie” scale items, with an additional 170 persons completing at least 2/3rds, but less than all the items. In order to avoid complete case bias and utilize persons who provided sufficient data, we first imputed the individual's mean for the existing scale items (which preserves inter-individual variation more accurately than, for instance, using the sample mean). For binomial distributions, this is the probability of a positive response. Simply using the individual's mean, however, meant that some items were not dichotomous (since they took on values between 0 and 1) but were not normally distributed either. Since the items were naturally dichotomous and we planned to factor them based on tetrachoric correlations, we used a probit transformation mapping the individuals' mean or probability of a positive response to either 0 or 1 so that tetrachoric correlations could be computed. The probit function is particularly consistent for tetrachoric correlations, because tetrachoric correlations map dichotomous items back to a continuous scale using an inverse probit function based on individuals' probability of a positive response in the process.

Goldberg's hierarchical factoring procedure begins with one factor—the overall domain or superfactor—at the highest or first tier. Factor analysis then extracts two factors, representing two distinct facets subsumed by the superfactor Another factor analysis then extracts three factors, representing three facets, on the third tier. The process is repeated until a factor emerges on which no items have their highest loading. Hierarchical factor structures have traditionally been defined by variance-covariance hierarchies, which imply correlated factors at each level. Goldberg's method originally produced orthogonal variance partitions at each level of the hierarchy in order to maximize simple structure and defining completely unique elements of a multi-dimensional scale. However, oblique rotation may also provide a useful picture of correlations horizontally or “within”, in addition to vertically or “across” the factorial hierarchy, so we implemented promax rotations. The result is a tree-like diagram or map, similar to a cluster analysis dendogram, depicting a broad trait's increasing differentiation from a molar composite dimension to molecular facets. A major conceptual distinction between Goldberg's method is that it takes a “top-down” approach to hierarchical structure, successively factoring a composite into more and more components until a level is reached at which components are essentially indivisible (save for reduction to discrete items). Conventional “bottom up” approaches work in the opposite direction, beginning at the item level. A parallel is seen in hierarchical clustering methods, in which a multi-tiered structure can be divined by divisive (top-down) or agglomerative (bottom-up) clustering algorithms.

We also examined the replicability of factors at each level using repeated split sample replication. This involved first drawing a bootstrap sample, randomly splitting it, and Procrustes-rotating the factor solution from one half to the other (using Stata's implementation of the algorithm to minimize Frobenius matrix norm) and examining factor stability, over 1000 bootstrap replicates. Congruence coefficients are often used to assess factor similarity, are mathematically equivalent to a Pearson correlation computed using unstandardized variables, and are thought to index both monotonicity and magnitude-similarity. However, the fact is the congruence coefficient is as sensitive to monotonicity relations and insensitive to loading magnitude as the Pearson correlation. For example, a factor with loadings of .8, .7, and .6 for three items would possess a congruence coefficient of 0.96 with a factor on which those same items load .3, .2, and .1; but the Gower index would be 0.5). Thus, instead of congruence coefficients, we focused on the Gower (Gower, 1971) similarity coefficient. Relative to the maximum possible absolute discrepancy between two factors, the Gower coefficient indicates the average percent similarity between factors.

Finally, we computed reliability for the scales formed by each factor's defining items (loadings > .4). Since item loadings on factors are typically not all equal, the resulting scales are not essentially tau-equivalent and thus Cronbach's alpha will not accurately estimate internal consistency reliability (Raykov, 1997), in addition to imposing a harsh penalty for short scales. We therefore provide Bentler's (2009) model-based composite reliability index, which allows variation in factor loadings and does not explicitly penalize scale length.

3. Results

Figure 1 shows the tree diagram for the Neuroticism domain. After extraction of the fourth factor, no items had their highest loading on subsequent factors. The four factors at the bottom tier (with representative items) were: Emotional Fragility (“Are your feelings rather easily hurt?”, “Are you easily hurt when people find fault with your work?”), Mood Lability (“Does your mood go up and down?”, “Are you sometimes bubbling over with energy and sometimes very sluggish?”), Nervous Tension (“Would you call yourself tense or high strung?”, “Would you call yourself a nervous person?”), and Rumination (“Do ideas run through your head so that you cannot sleep?”, “Do you suffer from sleeplessness?”).

Figure 1.

Tree structure resulting from Goldberg's sequential factor analytic method of mapping the hierarchical organization of the Eysenck Personality Inventory Neuroticism Scale. Variations in factor names across tiers reflect successive differentiation of content. Promax-rotated factor eigenvalues in underlined italics and items loading > .4 listed. Numbers by arrows are correlations between factor scores on different tiers. Numbers between factors reflect correlations within tiers. Within-tier correlations that cannot be depicted on the tree are: for the three factor solution, emotional reactivity and global anxiety r = .41; for the four factor solution, oversensitivity and nervous tension r = .42, oversensitivity and rumination r = .52, mood lability and rumination r = .65.

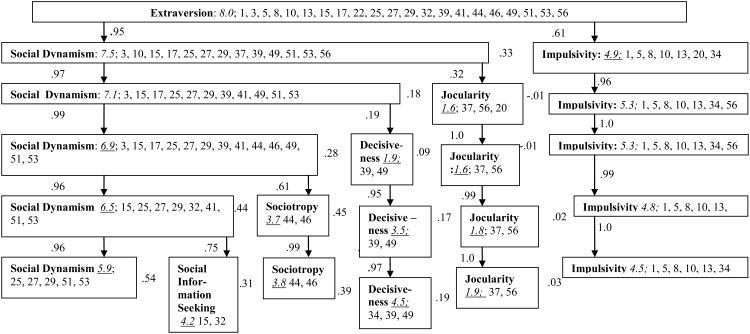

Figure 2 shows the tree diagram for EPI Extraversion; extraction stopped after six factors, as the seventh factor contained no items with their highest loadings. The six factors were Social Dynamism (“Can you usually let yourself go and enjoy yourself a lot at a lively party?”, “Can you easily get some life into a rather dull party?”), Social Information Seeking (“Generally, do you prefer meeting people to reading?”, “If there is something you want to know, would you rather talk to someone about it than look it up in a book?”), Sociotropy (“Do you like talking to people so much that you never miss a chance of talking to a stranger?”, “Would you be very unhappy if you could not see lots of people most of the time?”), Decisiveness (“Do you like doing things in which you have to act quickly?”, “Would you say that you were fairly self-confident?”), Jocularity (“Do you like playing pranks on others?”, “Do you love being with a crowd who plays jokes on one another?”), and Impulsivity (“Do you generally do and say things quickly, without stopping to think?”, “Do you stop and think something over before doing it?).

Figure 2.

Tree structure resulting from Goldberg's sequential factor analytic method of mapping the hierarchical organization of the Eysenck Personality Inventory Extraversion Scale. Variations in factor names across tiers reflect successive differentiation of content. Promax-rotated factor eigenvalues in underlined italics and items loading > .4 listed. Numbers by arrows are correlations between factor scores on different tiers. Numbers between factors reflect correlations within tiers. Within-tier correlations that cannot be depicted on the tree are: for the three factor solution, social dynamism and impulsivity r = .51; for the four factor solution, social dynamism and tomfoolery r = .18; social dynamism and impulsivity, r = .49; decisiveness and impulsivity r = .25; for the five factor solution, social dynamism and decisiveness r = .45; social dynamism and tomfoolery r = .20; for the six factor solution, social dynamism and impulsivity, r = .43; sociotropy and tomfoolery, r = .26; sociotropy and impulsivility, r = .36; decisiveness and impulsivity, r = .17; and for the six factor: social dynamism and sociotropy r = .43; social dynamism and decisiveness r = .53; social dynamism and tomfoolery r = .21; social dynamism and impulsivity r = .29; social information seeking and decisiveness r = .46; social information seeking and tomfoolery r = .12; social information seeking and impulsivity r = .51; sociotropy and tomofoolery r = .28; sociotropy and impulsivity r = .33; decisiveness and impulsivity r = .44.

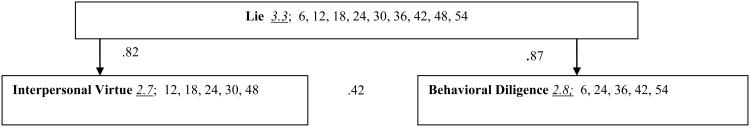

The “Lie” scale could be broken into two factors: Interpersonal Virtue (“Do you never lose your temper and get angry?”, “Do you never gossip?”), and Behavioral Diligence (“If you say you will do something, do you always keep your promise, no matter how inconvenient it might be to do so?”, “Would you always declare everything at customs, even if you knew that you could never be found out?”). The pattern matrices for the lowest tier solution from each hierarchy are depicted in Supplemental Tables 1-3.

Table 1 displays mean Gower similarity coefficients for factors at each tier of each domain over 1000 split sample replications. 95% Confidence Limitless for these coefficients were almost uniformly within .01 in each direction. Most factors showed relatively strong average percent agreements (>.7), although “Lie” scale subfactors showed a bit less stability. In general, greater replicability occurred for more specific factors at lower tiers of the hierarchies. Table 1 also shows model-based composite internal consistency reliability for the scales formed by the items loading over .4 on each factor (denoted in Figures 1-3). In general, composite reliabilities were adequate to good (.7-.8) even for small factors at lower tiers.

Table 1. Split Sample Factor Replicability Gower Coefficients and Composite Reliabilities.

| Lie | |||||

| Interpersonal Virtue |

Behavioral Diligence |

||||

| SG = .65 ρ11 = .63 |

SG = .71 ρ11 = .63 |

||||

| Neuroticism | |||||

| Emotional Reactivity |

Global Anxiety |

||||

| SG = .73 ρ11 = .85 |

SG = .68 ρ11 = .81 |

||||

| Global Anxiety |

Emotional Fragility |

Mood Lability |

|||

| SG = .76 ρ11 = .81 |

SG = .74 ρ11 = .81 |

SG = .70 ρ11 = .78 |

|||

| Nervous Tension |

Emotional Fragility |

Nocturnal Rumination |

Mood Lability |

||

| SG = .75 ρ11 = .81 |

SG = .78 ρ11 = .75 |

SG = .77 ρ11 = .75 |

SG = .78 ρ11 = .75 |

||

| Extraversion | |||||

| Social Dynamism |

Impulsivity | ||||

| SG = .71 ρ11 = .81 |

SG = .65 ρ11 = .66 |

||||

| Social Dynamism |

Impulsivity | Jocularity | |||

| SG = .73 ρ11 = .82 |

SG = .73 ρ11 = .72 |

SG = .73 ρ11 = .61 |

|||

| Social Dynamism |

Impulsivity | Jocularity | Decisiveness | ||

| SG = .78 ρ11 = .83 |

SG = .78 ρ11 = .72 |

SG = .77 ρ11 = .76 |

SG = .77 ρ11 = .50 |

||

| Social Dynamism |

Impulsivity | Decisiveness | Jocularity | Sociotrophy | |

| SG = .81 ρ11 = .83 |

SG = .81 ρ11 = .70 |

SG = .81 ρ11 = .70 |

SG = .81 ρ11 = .76 |

SG = .80 ρ11 = .74 |

|

| Social Dynamism |

Impulsivity | Decisiveness | Jocularity | Sociotrophy | Social Information Seeking |

| SG = .84 ρ11 = .83 |

SG = .84 ρ11 = .70 |

SG = .83 ρ11 = .70 |

SG = .85 ρ11 = .76 |

SG = .84 ρ11 = .74 |

SG = .84 ρ11 = .74 |

Notes: SG = Gower similarity coefficient for the factor across 1000 bootstrap split sample Procrustes rotations. The Gower coefficient ranges between 0 and 1, with 1 representing maximum possible similarity, or an exactly identical set of factor loadings, and 0 representing maximum dissimilarity. ρ11 = model-based internal consistency estimate (Bentler, 2009) from the composite formed by the items loading on that factor > .4.

Figure 3.

Tree structure resulting mapping the hierarchical organization of the Eysenck Personality Inventory Lie Scale. Variations in factor names across tiers reflect successive differentiation of content. Promax-rotated factor Eigenvalues in underlined italics and items loading > .4 listed. Numbers by arrows are correlations between factor scores on different tiers. The number between factors reflects within-tier correlation.

4. Discussion

4.1 Theoretical and Historical Implications

The facet structures we identified reflect a measurement operationalization of Neuroticism and Extraversion based on Eysenck's theory at the time (H. J. Eysenck, 1947, 1952). In contrast to the specific emotions (depression, anxiety, anger) of multi-faceted Five-Factor Model Neuroticism scales (Costa & McCrae, 1992), the EPI Neuroticism scale focuses specifically on anxiety. This emerged in the Rumination, as well as Nervous Tension facets. The latter reflects Eysenck's conceptualization of the biological underpinnings of Neuroticism, sympathetic nervous system reactivity (“Do you get palpitations or thumping in your heart?”). One facet of Big Five Neuroticism—vulnerability—reflects fluctuating mood and the potential to fall apart under criticism, and is emphasized on the EPI in both the Emotional Fragility and the Mood Lability facets.

Eysenck's theorized biological basis of Extraversion—the Ascending Reticular Activating System—is apparent in Extraversion facets reflecting social stimulation seeking and aversion to solitary, low-arousal activities like reading. Again, this conceptualization of Extraversion differs slightly from modern Big Five versions, which tend to spread the assessment of impulsiveness and similar constructs (i.e. constraint, sensation seeking) across Extraversion, Neuroticism, and Conscientiousness (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Sociability and positive affect have been argued to reflect the “core” facets of Extraversion currently (Lucas, Diener, Grob, Suh, & Shao, 2000). However, the EPI taps these qualities in a manner more consistent with the potential “dark side” of Extraversion. For instance, sociability is portrayed as more akin to the social dependence (e.g., “I would be very unhappy if I could not see many people most of the time”), or the concept of sociotropy, characterizing personality vulnerability to depression in some theories. Positive affect is represented in a mischievous form on the EPI through items involving pranks and practical jokes, in the Jocularity facet. The Interpersonal Information Seeking facet could easily be called “Bibliophobia” for the aversion to reading tapped by its items. One reason the EPI assesses potentially maladaptive qualities of Extraversion may be that it was used at one time in clinical settings. Note also that the impulsivity aspect of EPI Extraversion was subsequently relocated to Psychoticism on the EPQ (H. J. Eysenck, & Eysenck, S.B.G., 1975) and EPP (H. J. Eysenck, & Wilson, G.D., 1991).

Finally, the two facets of the Lie scale reflect tendencies similar to the other major social desirability scale of the era. Interestingly, however, the facets resemble recently developed behavioral indicators of Conscientiousness (Jackson et al., 2010), which reflect social propriety and responsibility in daily activities. In this sense, it seems to tap at least the perception of generally adaptive behavior.

4.2 Practical Implications

The EPI's hierarchical structure suggests that in some situations, it may be helpful to conduct facet-level analyses in the investigation of personality associations with an outcome. For example, in health psychology, focus on the superordinate level of Neuroticism and Extraversion has resulted in neglect of more specific traits subsumed by these dimensions. Specifically, many aspects of Neuroticism are generally maladaptive, but there is evidence for a “healthy” or “worried well” element of Neuroticism (Friedman, 2000). The EPI's somatic sensitivity items, appearing on the Nervous Tension factor and to a lesser extent, the Rumination facet, were originally intended to represent somatization or hypochondriasis, but may warrant consideration as health vigilance in some cases. Thus, the EPI facet structure may indicate less than full construct equivalence with Big Five measurement operationalizations of Neuroticism.

Similarly, comparison of findings based on the EPI and other Extraversion scales should be made with care. Modern Extraversion components such as sociability and positive mood are assessed in a more positive fashion, loading Extraversion scales toward the adaptive end of this construct. Impulsivity is placed under Neuroticism on the NEO-PI R, for instance, with a rather less pathological “Excitement Seeking” facet under Extraversion (Costa & McCrae, 1992). The EPI Extraversion content tends to be weighted toward less adaptive qualities, which may explain why scores reflect moderate but non-significant increasing mortality risk (Shipley, et al., 2007). Facet-level analyses may help identify the risk-conferring, versus inert or protective elements of Extraversion in situations such as this.

4.3 Strengths, Limitations, and Conclusions

Our findings arise from a sample of adults living in England, Scotland, and Wales, so the degree to which these factorial hierarchies generalize to other samples is unknown. However, these findings provide a starting point for facet analyses in other cohorts. It is also important to note that we do not suggest that analyses of the EPI broad Neuroticism and Extraversion scales be abandoned—to the contrary, they provide an important beginning for most personality research. A related consideration is at which level of aggregation to examine EPI facets. Rather than provide a one-size-fits-all recommendation, we suggest that the answer should depend largely on the specificity of constructs in the theory driving the research. One should also consider, however, of the degree of factor replicability and internal consistency of composite scales, which vary to some extent across factor tiers. For instance, the composite corresponding to the jocularity facet on the thee-factor tier of extraversion has only an internal consistency of .61, due to the presence of item 20, and would be inadvisable to use. Strengths include a large, population-representative sample, a new method of trait-tier mapping, intensive resampling approach to assess factor stability, reliability estimates free of most of the assumptions Cronbach's alpha relies upon for accuracy, and the production of a well defined set of facets for users of the EPI in HALS and similar samples.

Ultimately, the EPI's hierarchical structure can be seen as an early imprint of the facet composition implemented in subsequent Eysenck measures. Utilizing the facets individually, in subsets, or at different tiers as predictors can expand the scientific yield of research using the EPI. At a more general level, the EPI's facet structure and content provide a tool for assessing semantic and construct equivalency with other scales. In a more general sense, facet mapping o other instruments assessing broad personality constructs may provide a useful personality research tool.

Supplementary Material

We examined the hierarchical structure of the Eysenck Personality Inventory (EPI).

Neuroticism could be differentiated into 4 facets, Extraversion into 6, and the Lie scale into 2.

These facet reflect both early Eysenckian theory and practical utility in contemporary work.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by DHHS grant K08AG031328 (BPC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bentler P. Alpha, dimension-free, and model-based internal consistency reliability. Psychometrica. 2009;74(1):137–143. doi: 10.1007/s11336-008-9100-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaxter M. In: Sample and data collection, the health and lifestyle survey: a preliminary report. B M, Cox BD, Buckle ALJ, Fenner NP, Golding JF, Gore M, Huppert FA, Nickson J, Roth M, Stark J, Wadsworth MEJ, Whichelow M, editors. London: Health Promotion Trust; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory and NEO Five Factor Inventory: Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ. Dimensions of Personality. London: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner; 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ. The Scientific Study of Personality. London: Routledge and Kegan; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ. Manual of the Maudsley Personality Inventory. London: University of London Press; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Manual of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. London: Hodder & Stoughton; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Psychoticism as a dimension of personality. London: Hodder & Stoughton; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Wilson GD. Know Your Own Personality. London: Temple Smith; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Wilson GD. The Eysenck Personality Profiler. Sydney, Australia: Cymeon; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck SBG, Eysenck HJ. An improved short questionnaire for the measurement of extraversion and neuroticism. Life Sciences. 1964;305:1103–1109. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(64)90125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck SBG, Eysenck HJ, Barrett P. A revised version of the psychoticism scale. Personality and Individual Differences. 1985;6(1):21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Francis LL, Jackson CJ. Which version of the Eysenck Personality Profiler is best? 6-, 12-, or 20-items per scale. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;37:1659–1666. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman HS. Long-term relations of personality and health: Dynamisms, mechanisms, tropisms. Journal of Personality. 2000;68(6):1089–1107. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. Doing it all Bass-Ackwards: The development of hierarchical factor structures from the top down. Journal of Research in Personality. 2006;40(4):347–358. [Google Scholar]

- Gower JC. A general coefficient of similarity and some of its properties. Biometrics. 1971;27(4):857–871. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith RL, Peterson MH. The failure of social desirability measures to capture applicant faking behavior. Industrial and Organizationa Psychology. 2008;1(3):308–311. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JJ, Wood D, Bogg T, Walton KE, Harms PD, Roberts BW. What do conscientious people do? Development and validation of the Behavioral Indicators of Conscientiousness. Journal of Research in Personality. 2010;44:501–511. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas RE, Diener E, Grob A, Suh EM, Shao L. Cross-cultural evidence for the fundamental features of extraversion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79(3):452–468. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW. Positive and negative global self-esteem: A substantively meaningful distinction or artifactors? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70(4):810–819. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.4.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT. Social desirability scales: More substance than style. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1983;51(6):882–888. [Google Scholar]

- Raykov T. Scale reliability, Cronbach's coefficient alpha, and violations of essential tau-equivalence with fixed congeneric components. Mutivariate Behavioral Research. 1997;32(4):329–353. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3204_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipley BA, Weiss A, Der G, Taylor MD, Deary IJ. Neuroticism, extraversion, and mortality in the UK Health and Lifestyle Survey: A 21-year prospective cohort study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69(9):923–931. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815abf83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Web References

- Barrett P, Rolland JP. The Meta-Analytic Correlation Between the Big Five Personality Constructs of Emotional Stability and Conscientiousness: Something is Not Quite Right in the Woodshed. White Papers of Paul Barrett; Tulsa, OK: 2009. Retrieved from http://www.pbarrett.net/stratpapers/metacorr.pdf?cls=file. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.