Abstract

Objectives

There is a well-established link between psychological distress, work-related stress and sleep. The aim of this study was to test the hypothesis that work-family conflict was associated with sleep deficiency both cross-sectionally and longitudinally while controlling for potential covariates.

Methods

In this two-phase study, a workplace health survey was collected from a cohort of patient care workers (n=1,572) at two large hospitals. Follow-up was collected nearly two years later in a subsample (n=102). Self-reported measures included work-family conflict, socio-demographics, workplace factors, psychological distress, and outcomes of sleep duration, sleep insufficiency, and sleep maintenance. Bivariate associations (P<0.2) from the baseline sample were used to build multivariable logistic regression models.

Results

The participants were 90 % women with a mean age of 41 (±11.7) years. At baseline, after adjusting for covariates, higher levels of work-family conflict were significantly associated with sleep deficiency, short sleep duration and perceived sleep insufficiency, but not with sleep maintenance problems. Higher levels of work-family conflict also predicted sleep insufficiency at follow-up nearly two years later. None of the other variables were associated with sleep outcomes longitudinally.

Conclusion

This is the first study to determine the predictive and cross-sectional associations of work-family conflict on sleep deficiency, also controlling for other measures of job stress and psychological distress. The results indicate that future interventions on sleep deficiency in patient care workers should include a specific focus on work-family conflict.

Keywords: Sleep, Work-Family Conflict, Psychological Distress, Nurses

Introduction

Sleep deficiency has been shown to affect both psychological wellbeing 1 and work performance 2. The term sleep deficiency includes three components: short sleep duration, sleep maintenance problems, and/or sleep insufficiency. These components have independently been associated with pain and functional limitations 3, and have a negative influence on quality of life 4. The components also represent a substantial economic burden to society 5. Patient care workers are a high-risk population for sleep deficiency. A recent study showed the prevalence of self-reported insomnia symptoms and sleep deficiency being 40 % and 57 %, respectively 3.

Patient care workers are vulnerable presumably because their work schedules often involve shift and night work 6. Long shifts (>8 hours) and a short recovery time between shifts (<10 hours), have been associated with sleep disturbance and poor sleep quality 7. Patient care workers also struggle with several risk factors for sleep deficiency, as they are prone to work-family conflict 8,9, psychosocial stress and numerous workplace hazards 10.

The negative effects from components like sleep maintenance problems are well documented. Insomnia symptoms are commonly defined as a difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep, and/or experiencing a non-restorative sleep with decreased daytime functioning, lasting at least four weeks 11. A primary insomnia diagnosis is only given by a trained physician during a clinical interview excluding other explanations like: substance abuse/medication, respiratory disorder, comorbid conditions, time zones and/or other events happening during sleep (nightmares, night terrors, sleep walking or parasomnias). The estimated cost and impact of insomnia symptoms is staggering. A recent study among US workers reported a prevalence as high as 23.2 %, and calculated that the annual cost of insomnia symptoms rose above $60 billion when they estimated the effect of lowered work performance and increased absenteeism 12.

In addition to insomnia, experimental studies on sleep have shown several adverse effects from the components sleep insufficiency and short sleep duration 4. A shortened duration of habitual sleep, e.g., < 6 hours / night has been associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality, diabetes, obesity, hypertension, cardiovascular risk and lower psychological wellbeing 4,13,14. Perceived sleep insufficiency has been associated with lower supervisor support and lower job satisfaction 3, lower physical activity and exercise 15 and increased risk for mental disorders 16.

Several studies associate job stress with both sleep deficiency 3,17, and the development of psychological disorders 16,18. The concept of job stress has been defined in part by two major models, the demand-control model 19 and later the demand-control-support model 20. Although both these models have explanatory value, they have been challenged both regarding their somewhat narrow conceptualization of job stress and how they choose to measure these job stress concepts21.

A factor proven salient in several studies of job stress is work-family conflict 22,23. The trade-off between the domestic work-load and job related work-load, as well as the planning, guilt and maneuvering to fit schedules and interests, are identified as major causes of stress 23. A meta-analysis on the work-family interface distinguishes between demands from the private sphere conflicting with work, and demands from work conflicting with home life 24. Several factors have been shown to influence the experience of work-family conflict. Social support at work has been identified as salient in both negative health outcomes and perceived levels of conflict 25. Marital status, child caring and traditional sex roles have also been shown to impact work-family conflict, as females have a higher workload at home and less time to recover from work 24,26. On an organizational level, both work flexibility and the option to receive paid sick leave has been shown to affect the level of conflict reported 27,28.

Nurses have been shown to have considerable more problems with work interfering with home life, than the other way around 9. This coincides with a study showing how females to a larger extent than men, tend to carry work stress into home life 29. Nurses are a mostly female population, and it has been argued that work-to-family conflict is the foremost construct of interest in these workers 9.

The connection between the individual experience of stress and disturbance of sleep is well established 30. Previous studies have shown that work-family conflict is associated with perceived sleep quality 31,32,33. A recent study reported a negative association between work-family spillover and sleep quality 31. However, this study was limited by a small sample size and only investigated one component of sleep deficiency, the global quality of sleep 31. Another study investigating the association had a larger sample size, but lacked adequate information about sleep, as they relied on a single item assessing sleep quality 32. Also, none of these studies investigated the effects longitudinally. Thus, the question remains whether work-family conflict influences other components of sleep deficiency to a significant degree, and whether this association remains when other measures of work stress and psychological distress are controlled for. The associations and predictive relationship between these constructs should be investigated to shape interventions and support further investigation through prospective cohort studies.

The aims of the current study were 1) to investigate cross-sectional associations between work-family conflict and the composite sleep deficiency as well as its components in patient care workers, controlling for the potential confounders iso-strain, psychological distress and socio-demographics; and 2) to investigate longitudinally in a subset of workers, whether work-family conflict identified at baseline increases the risk of sleep deficiency and/or its components at follow-up over two years later, when controlling for baseline outcome.

Methods

Study Design

The data were collected as part of the “Be Well, Work Well” project at the Harvard School of Public Health, Center for Work, Health, and Well-being and used to inform the development of an integrated health protection/health promotion intervention. A survey was conducted in two academic hospitals in New England, USA between October 2009 and February 2010. We approached workers who had direct patient care responsibilities and were employed at the hospitals for more than 20 hours per week during 2008. A subset of respondents at one of the hospitals participated in an ancillary study that involved assessment of cardiovascular biomarkers and a follow-up survey. Follow-up visits took place from August to November 2011.

The local institutional Human Research Committees approved the study and all procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants and Data Collection

At time 1, 2000 patient care workers were randomly selected and invited by email to complete the survey online. We sent 2 email reminders during the 4 weeks following the first contact, and then mailed a paper version of the questionnaire to those who had not finished the survey online. After 2 more weeks we sent a third email reminder and a second paper survey to all non-responders. A total of 1572 (79%) completed at least 50% of the survey. Details of the main sampling procedure has been described elsewhere 3.

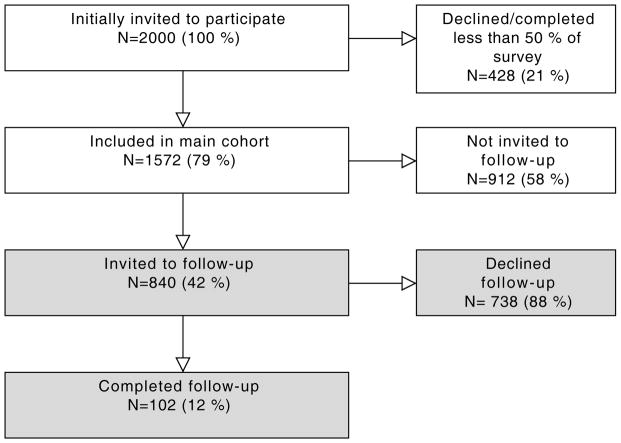

All patient care workers at one of the two hospitals who completed the initial survey were contacted via e-mail, reminding them of their participation in the original survey and asking about their interest in the ancillary study. Out of 840 employees who were re-contacted after completing the survey, a total of 102 (12.1 %) completed the follow visit and blood draw. The follow-up survey required an in-person meeting, so a much lower participation was anticipated. The flow of participants is illustrated in figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The Flow of Study Participants from Main Cohort to Follow-up, Two Years Later.

Measures

Self-Reported Sleep Outcomes

All sleep outcomes were reported both at baseline and at follow-up. Short sleep duration was assessed by asking participants how many hours they slept each night over the previous four weeks, and was defined as less than 6 hours per night in the last month. An item asking how often they had problems with waking up during the night assessed sleep maintenance. These items had four response categories ranging from “not at all in the last 4 weeks” to “3 or more times a week”. Having sleep maintenance problems was defined as the problem being present 3 nights per week or more in the last month. Sleep insufficiency was measured by asking how often participants “felt rested upon awakening” with five response categories ranging from “never” to “always”. The presence of sleep insufficiency was defined as responding “never” or “rarely”. Sleep deficiency was operationalized as the presence of one or more of these components.

Independent variable

Work-family conflict was measured using a five item scale 34. The following instruction and items were included in the scale: How much do you agree or disagree with the following statements: (1) The demands of my work interfere with my family or personal time. (2) The amount of time my job takes up makes it difficult to fulfill family or personal responsibilities. (3) Things I want to do at home do not get done because of the demands my job puts on me. (4) My job produces strain that makes it difficult to fulfill my family or personal duties. (5) Due to work-related duties, I have to make changes to my plans for family or personal activities. Response categories ranging from 5 = “Strongly Agree” to 1 = “Strongly Disagree” yielding a score between 5–25, where higher scores indicate greater work-family conflict. We trichotomized the score into low (5–12), intermediate (13–17), high (18–25) conflict, as done in previous studies 8, making the variable more intutive and easier to interpret.

Covariates from baseline measures

Covariates were selected a priori based on variables known to be associated with sleep quality, duration and sufficiency. These covariates include socio-demographics, work-related stress, psychological distress and night work.

Socio-demographic factors were obtained through participants reporting their age (years), gender, race/ethnicity (Hispanic, White, Black and mixed race/others), occupation (staff nurse, patient care associate and others), ability to pay bills (great deal of difficulty; some difficulty; a little difficulty; no difficulty; don’t know; refused), height (inches) and weight (pounds). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the self-reported weight and height (kilos per square meter).

Work-related stress was assessed by self-reported job demands, decision latitude, coworker support and supervisor support. A modified version of the Job Content Questionnaire19,35 measured job demands, decision latitude, co-worker and supervisor support. Job demands were assessed through 5 items that were weighted and summed yielding a scale from 12 to 48 35. Decision latitude was assessed through 9 items created as a weighted sum of decision authority and skill discretion from the Job Content Questionnaire. Co-worker support was assessed through 2 items with 5 response categories summed, yielding a scale from 2–1035. Supervisor support was assessed through 3 items with 5 response categories summed and scaled giving a scale of 3 to 15 35.

Iso-strain was a composite variable assessed by measuring job demands, decision latitude and social support. Social support was in the composite variable defined as the participant level of co-worker and supervisor support. All three variables were dichotomized by their medians into low/high categories 18. Iso-strain was defined as high job demands, low decision latitude and low social support 18.

Severe psychological distress was measured with the K-6 Nonspecific Distress Scale. A summative 6-item scale, with responses to each item ranging from 0 indicating “no distress”, to 4 indicating “distress all of the time” yielded a range of scores between 0–24 36.

Night work was quantified from administrative payroll data and calculated as average night work-hours per month (between 10 PM and 6 AM), calculated from October 2008 until August 2009. Excluding shifts shorter than 4 hours, the variable was trichotomized into 0–6 hours, >6–72 hours or more than 72 hours per month.

Data analysis

Using the baseline data on the larger sample, the characteristics of workers who had sleep deficiency, sleep maintenance, sleep insufficiency and/or short sleep duration were compared to those who did not. We used the independent sample t-test for continuously measured characteristics and the Pearson’s Chi-square test or Fisher Exact Chi-Square test for categorical measures. To assess the multivariable associations of work family conflict and sleep controlling for the potential confounders, we used multiple logistic regression analysis. Covariates that had a P-value <0.2 in the bivariate analyzes were included in the multivariate models ensuring that variables were relevant, without a too stringent exclusion.

To assess aim 2, the longitudinal relationship between work-family conflict on subsequent sleep, we computed multiple logistic regression analysis using the subsample. We regressed sleep at time 2 on work family conflict at baseline, and controlled for baseline measures of sleep and the covariates determined to be associated with sleep at baseline. All analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.3. (SAS Institute, Inc. Cary, NC)

Results

Participant characteristics

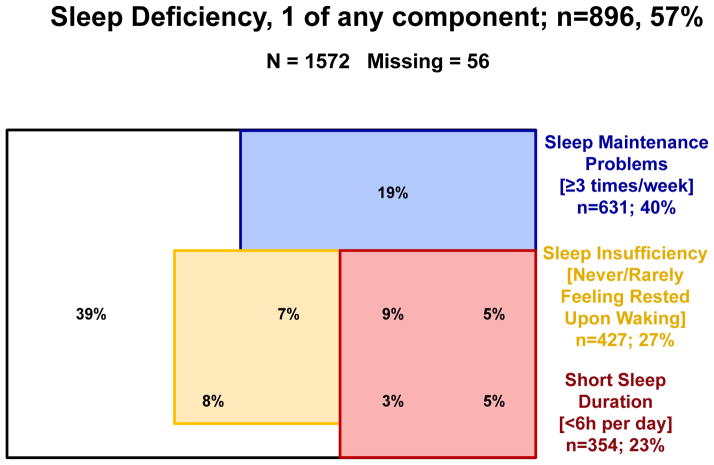

The participants (n=1572) were 90 % women with a mean age of 41.4 years (SD, 11.7 years). The majority was white (79 %), married or living with a partner (66 %), staff nurses (70 %) with a college degree (53 %) In our main sample 63 % (n=896) reported sleep deficiency, 23 % (n=354) reported short sleep duration, 27 % (n=428) reported sleep insufficiency and 40 % (n=631) reported sleep maintenance. Figure 2 illustrates the number of participants with each sleep outcome, overlap between outcomes and missing data.

FIGURE 2.

Participant frequencies, distribution and overlap on baseline sleep outcomes. Sleep maintenance is represented by the blue square, short sleep duration by the red square and sleep insufficiency by the yellow square.

Cross-sectional analyses of overall sample

Sleep deficiency and the components are all significantly associated with work-family conflict, such that greater work-family conflict is associated with a higher prevalence of sleep deficiency (Table 1). Similarly for each of the components of sleep deficiency, greater work-family conflict is associated with greater prevalence of sleep disturbance. Covariates associated with greater prevalence of sleep deficiency include higher BMI, having an occupation other than staff nurse or patient care associate, having iso-strain and/or having at least some difficulty paying bills. Results were similar for the components of sleep deficiency; though only higher work-family conflict and more psychological distress were negatively associated with all sleep outcomes (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

In our main sample, table 1 shows the frequency (%) or mean (SD) of respondent characteristics. The figures are listed by the presence or absence of sleep deficiency, short sleep duration, sleep maintenance and sleep insufficiency, with P-value for associations with outcomes

| Characteristics | Sleep Deficiency

|

P-Value1 | Short Sleep Duration

|

P-Value1 | Sleep Maintenance Problems

|

P-Value1 | Sleep Insufficiency

|

P-Value1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N=896) | No (N=620) | Yes (N=354) | No (N=1115) | Yes (N=631) | No (N=872) | Yes (N=428) | No (N=1075) | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Work-Family Conflict | ||||||||||||

| 0: Low | 378 (51.6%) | 355 (48.4%) | 143 (20.2%) | 564 (79.8%) | 269 (37.0%) | 459 (63.0%) | 144 (19.9%) | 580 (80.1%) | ||||

| 1: Medium | 310 (65.1%) | 166 (34.9%) | < 0.0001 | 115 (24.7%) | 351 (75.3%) | 0.0003 | 222 (47.1%) | 249 (52.9%) | 0.0004 | 158 (33.5%) | 314 (66.5%) | < 0.0001 |

| 2: High | 196 (68.5%) | 90 (31.5%) | 89 (32.2%) | 187 (67.8%) | 133 (46.8%) | 151 (53.2%) | 123 (43.0%) | 163 (57.0%) | ||||

| Psych Distress | 3.0 (± 3.67) | 1.9 (± 2.66) | < 0.0001 | 3.2 (± 3.68) | 2.3 (± 3.21) | 0.0002 | 3.1 (± 3.69) | 2.2 (± 3.02) | < 0.0001 | 3.7 (± 4.11) | 2.1 (± 2.83) | < 0.0001 |

| Night Work | ||||||||||||

| 0: 0–6 hrs monthly | 523 (60.3%) | 344 (39.7%) | 188 (22.4%) | 651 (77.6%) | 379 (44.2%) | 479 (55.8%) | 228 (26.6%) | 629 (73.4%) | 0.18 | |||

| 1: >6 hrs but < 72 | 221 (55.7%) | 176 (44.3%) | 0.27 | 99 (25.4%) | 291 (74.6%) | 0.17 | 160 (40.6%) | 234 (59.4%) | 0.09 | 121 (30.6%) | 274 (69.4%) | |

| 2: 72+ | 152 (60.3%) | 100 (39.7%) | 67 (27.9%) | 173 (72.1%) | 92 (36.7%) | 159 (63.3%) | 79 (31.5%) | 172 (68.5%) | ||||

| Age (yrs) | 41.9 (±11.48) | 40.5 (±11.95) | 0.03 | 42.3 (±11.45) | 40.9 (±11.77) | 0.06 | 42.9 (±11.56) | 40.1 (±11.60) | < 0.0001 | 39.6 (±10.88) | 42.0 (±11.93) | 0.0003 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.6 (±5.48) | 25.9 (±4.95) | 0.01 | 27.3 (±5.84) | 26.0 (± 5.04) | 0.0004 | 26.5 (±5.37) | 26.1 (±5.22) | 0.15 | 26.4 (±5.45) | 26.3 (± 5.22) | 0.77 |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| 1: Male | 81 (57.0%) | 61 (43.0%) | 0.60 | 29 (21.2%) | 108 (78.8%) | 0.39 | 60 (42.6%) | 81 (57.4%) | 0.92 | 41 (29.3%) | 99 (70.7%) | 0.77 |

| 2: Female | 806 (59.3%) | 553 (40.7%) | 323 (24.5%) | 998 (75.5%) | 567 (42.1%) | 780 (57.9%) | 379 (28.1%) | 969 (71.9%) | ||||

| Marital Status | ||||||||||||

| 0: Single / living alone | 303 (59.8%) | 204 (40.2%) | 0.70 | 134 (26.9%) | 364 (73.1%) | 0.07 | 198 (39.5%) | 303 (60.5%) | 0.16 | 141 (28.1%) | 360 (71.9%) | 0.91 |

| 1: Married / living with partner | 572 (58.7%) | 402 (41.3%) | 213 (22.6%) | 730 (77.4%) | 419 (43.4%) | 547 (56.6%) | 275 (28.4%) | 692 (71.6%) | ||||

| Race | ||||||||||||

| 1: Hispanic | 35 (54.7%) | 29 (45.3%) | 13 (21.0%) | 49 (79.0%) | 0.001 | 18 (28.6%) | 45 (71.4%) | 0.0006 | 20 (31.7%) | 43 (68.3%) | 0.92 | |

| 2: White | 703 (59.4%) | 481 (40.6%) | 0.89 | 261 (22.4%) | 905 (77.6%) | 528 (44.8%) | 650 (55.2%) | 330 (28.1%) | 845 (71.9%) | |||

| 3: Black | 92 (58.6%) | 65 (41.4%) | 50 (35.2%) | 92 (64.8%) | 48 (31.8%) | 103 (68.2%) | 45 (29.4%) | 108 (70.6%) | ||||

| 4: Mixed race / other | 53 (60.2%) | 35 (39.8%) | 27 (33.3%) | 54 (66.7%) | 30 (34.1%) | 58 (65.9%) | 24 (27.3%) | 64 (72.7%) | ||||

| Occupation | ||||||||||||

| 1: Staff Nurse | 610 (57.2%) | 457 (42.8%) | 238 (22.7%) | 812 (77.3%) | 447 (42.2%) | 612 (57.8%) | 291 (27.5%) | 768 (72.5%) | ||||

| 2: Patient Care Associate | 67 (57.8%) | 49 (42.2%) | 0.02 | 31 (31.3%) | 68 (68.7%) | 0.07 | 35 (30.7%) | 79 (69.3%) | 0.02 | 32 (28.1%) | 82 (71.9%) | 0.38 |

| 3: Other, please specify | 216 (66.1%) | 111 (33.9%) | 84 (26.8%) | 230 (73.2%) | 147 (45.4%) | 177 (54.6%) | 102 (31.5%) | 222 (68.5%) | ||||

| Iso-Strain | ||||||||||||

| 0: No | 697 (57.3%) | 520 (42.7%) | 0.005 | 274 (23.0%) | 915 (77.0%) | 0.20 | 504 (41.7%) | 705 (58.3%) | 0.48 | 334 (27.7%) | 872 (72.3%) | 0.02 |

| 1: Yes | 119 (68.4%) | 55 (31.6%) | 46 (27.5%) | 121 (72.5%) | 77 (44.5%) | 96 (55.5%) | 63 (36.4%) | 110 (63.6%) | ||||

| Difficulty paying bills? | ||||||||||||

| 0: Little difficulty w/bills | 619 (56.8%) | 471 (43.2%) | 0.002 | 242 (22.6%) | 827 (77.4%) | 0.02 | 455 (42.1%) | 625 (57.9%) | 0.81 | 262 (24.3%) | 817 (75.7%) | < 0.0001 |

| 1: At least some difficulty w/ bills | 229 (66.2%) | 117 (33.8%) | 96 (28.9%) | 236 (71.1%) | 142 (41.4%) | 201 (58.6%) | 144 (41.9%) | 200 (58.1%) | ||||

P-values for continuous variables were based on t-tests; P-values for categorical variables were based on Chi-Square. Significant P-values are bolded.

For multivariable analysis of work family conflict and sleep deficiency we included the variables from the bivariate analyses with p-values <0.20 to select relevant variables without excluding potentially important covariates (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Cross-sectional multivariate associations between selected variables (P<0.2) from bivariate analyzes

| Independent Variables | Sleep Deficiency | Short Sleep Duration | Sleep Maintenance Problems | Sleep insufficiency | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P-Value | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P-Value | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P-Value | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P-Value | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Work-Family Conflict | ||||||||||||

| 1: Medium vs. 0: Low | 1.57 | 1.19 – 2.07 | 0.0008 | 1.23 | 0.88 – 1.72 | 0.04 | 1.34 | 1.03 – 1.74 | 0.08 | 1.68 | 1.25 – 2.27 | <.0001 |

| 2: High vs. 0: Low | 1.70 | 1.20 – 2.40 | 1.64 | 1.11 – 2.41 | 1.26 | 0.91 – 1.74 | 2.36 | 1.67 – 3.34 | ||||

| Psychological Distress | 1.11 | 1.06 – 1.16 | <.0001 | 1.06 | 1.02 – 1.11 | 0.004 | 1.10 | 1.06 – 1.14 | <.0001 | 1.10 | 1.05 – 1.14 | <.0001 |

| Night-Work Category | ||||||||||||

| 1: >6 hrs. but < 72 vs. 0: 0–6 hrs. monthly | 1.67 | 1.16 – 2.40 | 0.02 | 0.93 | 0.69 – 1.25 | 0.11 | 0.90 | 0.65 – 1.24 | 0.72 | |||

| 2: 72+ vs. 0: 0–6 hrs. monthly | 1.47 | 0.98 – 2.20 | 0.70 | 0.50 – 0.98 | 1.04 | 0.73 – 1.49 | ||||||

| Age (years) | 1.01 | 1.00 – 1.02 | 0.01 | 1.02 | 1.01 – 1.03 | 0.003 | 1.02 | 1.01 – 1.03 | <.0001 | 0.99 | 0.98 – 1.00 | 0.11 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1.02 | 0.99 – 1.04 | 0.20 | 1.03 | 1.00 – 1.05 | 0.06 | 1.01 | 0.99 – 1.04 | 0.23 | |||

| Marital Status | ||||||||||||

| 1: Married / living with partner vs. 0: Single / living alone | 0.76 | 0.57 –1.03 | 0.08 | 1.18 | 0.92 – 1.50 | 0.20 | ||||||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| 2: White vs. 1: Hispanic | 1.80 | 0.68 – 4.80 | 1.65 | 0.86 – 3.17 | ||||||||

| 3: Black vs. 1: Hispanic | 4.35 | 1.52 – 12.5 | 0.0008 | 0.94 | 0.45 – 1.96 | 0.03 | ||||||

| 4: Mixed race / other vs. 1: Hispanic | 3.56 | 1.16 – 10.9 | 1.07 | 0.48 – 2.39 | ||||||||

| Occupation | ||||||||||||

| 2: Patient Care Associate vs. 1: Staff Nurse | 0.94 | 0.56 – 1.59 | 0.13 | 0.61 | 0.29 – 1.27 | 0.34 | 1.02 | 0.59 – 1.74 | 0.83 | |||

| 3: Other, please specify vs. 1: Staff Nurse | 1.36 | 1.00 – 1.85 | 1.07 | 0.73 – 1.56 | 1.10 | 0.81 – 1.49 | ||||||

| Iso-Strain | ||||||||||||

| 1: Yes vs. 0: No | 1.33 | 0.90 – 1.97 | 0.15 | 1.17 | 0.76 – 1.79 | 0.48 | 1.06 | 0.72 – 1.56 | 0.76 | |||

| Difficulty paying bills? | ||||||||||||

| 1: At least some difficulty w/ bills vs. 0: Little difficulty w/ bills | 1.24 | 0.92 – 1.66 | 0.16 | 1.09 | 0.78 – 1.53 | 0.60 | 1.80 | 1.35 – 2.39 | <.0001 | |||

Significant P-values are bolded. All variables are not tested for all outcomes because of the selection criteria (P<0.2)

After adjusting for covariates, higher work-family conflict was significantly associated with sleep deficiency (“medium” vs. “low” OR 1.57, 95 % CI, 1.19–2.07, “high” vs. “low” OR 1.70, 95 % CI, 1.20–2.40, P=0.0008). An increase in severe psychological distress and older age was also significantly associated with increased sleep deficiency in the multivariable analysis.

Looking at the components of sleep deficiency, higher work-family conflict was associated with sleep insufficiency (“medium” vs. “low” OR 1.68, 95 % CI, 1.25–2.27, “high” vs. “low” OR 2.36, 95 % CI, 1.67–3.34, P<0.0001) and short sleep duration (“medium” vs. “low” OR 1.23, 95 % CI, 0.88–1.72, “high” vs. “low” OR 1.64, 95 % CI, 1.11–2.41, P=0.04) when controlled for covariates. Also, the variable displayed clear trends of higher work-family conflict being associated with increased risk of sleep maintenance (Table 2).

Cross-sectional analyses of the subsample (n=102)

Our subsample was similar to the overall sample on socio-demographic characteristics and outcomes with the exception of race/ethnicity. The subsample had a higher percentage of white patient care workers than the main sample. Our subsample was predominantly white (91 %), female (97 %), nurses (68 %) with a college degree (65 %) and a mean age of 40.8 (SD 11.9) years. Sleep deficiency was reported by 64 (63 %) of the participants at baseline. With similar distributions in the variables there was a reasonable assumption that the baseline multivariable models could be replicated in the biomarker subsample.

Longitudinal analysis of subsample (n=102)

After controlling for baseline scores in sleep outcomes, work-family conflict was no longer significantly associated with sleep deficiency. When the components were investigated separately, higher work-family conflict was significantly associated with perceived sleep insufficiency (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Longitudinal associations between Baseline Outcome, Work-Family Conflict and Sleep Outcomes at follow-up

| Independent variables | Sleep Deficiency | Short Sleep Duration | Sleep Maintenance | Insufficient Sleep | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Odds Ratio (95 % CI) | P-value | Odds Ratio (95 % CI) | P-value | Problems Odds Ratio (95 % CI) | P-value | Odds Ratio (95 % CI) | P-value | |

| Baseline Outcome | 5.57 (2.14 – 14.5) | 0.0004 | 12.0 (4.14 – 34.7) | <.0001 | 6.67 (2.50 – 17.8) | 0.0001 | 13.4 (4.59 – 39.4) | <.0001 |

| Work-Family Conflict: | ||||||||

| 1: Medium vs 0: Low | 2.37 (0.64 – 8.75) | 0.43 | 2.81 (0.81 – 9.76) | 0.27 | 0.67 (0.21 – 2.10) | 0.31 | 5.10 (1.47 – 17.7) | 0.04 |

| 2: High vs 0: Low | 1.15 (0.39 – 3.45) | 1.58 (0.43 – 5.85) | 0.45 (0.15 – 1.33) | 2.15 (0.61 – 7.52) | ||||

Significant P-values are bolded

Psychological distress, iso-strain and socio-demographic factors did not predict sleep outcomes at follow-up. Tests of interaction effects examining the effect of work-family conflict combined with each baseline sleep outcome, on sleep outcomes at time 2, revealed no significant interactions (data not shown).

Discussion

The goals of the current study were to assess how work-family conflict was cross-sectionally associated with sleep deficiency (sleep maintenance problems, short sleep duration and/or sleep insufficiency) when controlling for psychological distress, other work stress variables, and socio-demographic factors. Furthermore, we aimed to see whether or not work-family conflict at baseline predicted sleep outcomes at follow-up in a subsample. In baseline cross-sectional analyses, we found significant associations of higher levels of work-family conflict and increased risk of the composite sleep deficiency. Increased psychological distress and older age also significantly increased the risk for sleep deficiency. All associations remained significant when controlling for socio-demographic and occupational covariates.

In the subsample (n=102) that participated in the follow-up, higher levels of work-family conflict was not associated with sleep deficiency. However, higher levels of work-family conflict significantly predicted sleep insufficiency and showed a negative trend in short sleep duration. The effect of work-family conflict on subsequent sleep outcomes, when controlling for psychological distress and iso-strain, suggests that sleep and work stress studies should include a measure of conflict in the work-family interface. Work-family conflict was also the only significant predictor in our two-year follow-up, making role conflict and scheduling a prime subject both in future longitudinal studies and interventions targeting sleep deficiency and work stress.

A diary study of 91 employees studied for 14 consecutive days highlighted work-family conflict as a separate, salient construct in the work stress paradigm 22. That work-family conflict in our study was strongly associated with sleep deficiency when controlling for job strain accentuates this, and is consistent with previous work 33. In our study we also controlled for co-worker/supervisor support, severe psychological distress and socio-demographic factors, and the influence of work-family conflict remained. Univariate analyses showed a significant relationship between iso-strain and sleep deficiency. However this association disappeared when controlled for work-family conflict, among other covariates. The relationship between iso-strain components and sleep deficiency is well established 17, however this study could be viewed as an argument for work-family conflict being the salient factor in the relationship between work stress and sleep deficiency. It is at the least a strong argument to include this variable in future studies.

Our results showed a predictive and associative relationship between high work-family conflict and not feeling rested upon awakening, which may have several possible explanations. One possible mechanism is that the trade-off between work and family duties cause rumination and worry, two cognitive processes linked to increased arousal 37. Arousal from cognitive processes have been claimed to both cause disturbed sleep and to influence the individuals perception of their sleep 38. Another possible explanation is a previous finding demonstrating how sleep suffered from prioritizing between work, family and sleep 39. The conservation of resources theory is frequently cited in the work-family conflict field. It claims that work-family stress is often caused by a threat of losing resources, a loss of resources, or a lack of expected gain in resources 40. Resources that apply to a work-life setting could be threats to ones image as good wife or husband; personal characteristics like work-related confidence and self-esteem; or material resources like time, knowledge and money 40.

In line with the principles of conservation of resources theory, the trend in short sleep duration could also partly explain the link between work-family conflict and sleep insufficiency. The results from our subsample do not have the power or measure-points to properly describe any causal mechanisms. However, the many demands in work and home life can restrict the actual hours available for sleeping, either this is voluntary or not, which would explain the reported sleep insufficiency. The results in this study and previous work indicate that sleep is the loser when we aim to increase/protect other resources. The down prioritizing of sleep should therefore be highlighted as a important part of the work-life domain, and made salient in organizational health promotion programs 39.

Psychological distress was strongly associated with all sleep outcomes at baseline, but it was not associated with any outcomes longitudinally. The cross-sectional associations support numerous other studies showing a link between psychological distress and sleep 1,16. One possible explanation for the lack of association at follow-up is that psychological distress has a more temporary effect on sleep outcomes than work-family conflict. Earlier studies have claimed that sleep maintenance problems are most likely an intermediate phenotype in depression 41, but the two are still separate co-occurring disorders influencing each other. This coincides with other studies reporting a bi-directional relationship between insomnia and depression 1. The natural course of unipolar depression will often lead to recovery within 6 months, even without treatment 42 and, in a small sample such as ours, a change in depressive disorders could very well influence the effects at follow-up. The concept of sleep deficiency as a comorbid condition in psychiatric disorders is evident looking at DSM-IV. Sleep maintenance problems are part of the criteria in 19 DSM-IV diagnoses, and it has been suggested that sleep deficiency is a trans-diagnostic mechanism contributing to the development and maintenance of mental disorders 43. The sample size at follow-up does not allow for an investigation of the cross-sectional relationship between sleep outcomes and psychological distress at time 2, an important factor that might influence the sleep outcomes in this study.

Limitations

This analysis has some limitations, which will now be considered. The cross-sectional approach in the initial analyses does not allow for any causal inferences regarding directionality or mechanisms regarding the effect of work-family conflict and psychological distress on sleep. We do have a small sample with two time points, but two time points are only slightly better than one, and mediating mechanisms cannot be described with this approach. Also, the small sample was only collected from one of the two hospitals, with a low response rate, making the selection more vulnerable for bias. However, the low response rate was expected seeing as the ancillary study required an in-person meeting and a blood sample from participants.

Another limitation is that this study has no measure of the amount of extra work shifts or overtime that workers may have done. Patient care associates and other staff, which consist mainly of support staff, are lower wage earners than their staff nurse counterparts. These lower wage earners may have overtime pay or other jobs that also may contribute to increased work-family conflict and to sleep deficiency.

The follow-up in this study is limited to a very small number of subjects. The effects of a small sample size are evident looking at the Odds Ratios of higher work-family conflict on sleep deficiency in the small and large samples. The Odds Ratios in the small sample are actually higher than in the large one, but are still non-significant. Several longitudinal and intervention studies on larger samples will be needed to understand the causal mechanisms of how work-family conflict affects sleep. This is however, the first study to examine this with a follow-up. Furthermore, sleep outcomes were self-reported and so were the other measures in this study. Future studies on work-family conflict and the sleep outcomes might benefit if the components of sleep deficiency were measured more objectively through actigraphy or polysomnography.

Conclusion

This study is the first study to investigate the effects of work-family conflict on sleep deficiency in patient care workers while controlling for several important covariates and using follow-up data. Work-family conflict was the only variable that could predict sleep problems two years later when controlling for baseline sleep outcomes. Patient care workers are an occupational group with a very high prevalence of sleep deficiency, and the deficiency is tied to musculoskeletal pain, functional limitation and psychological distress 3. The results from this study indicate that future studies and interventions on sleep deficiency and occupational health should include a specific focus on work-family conflict.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (U19 OH008861) for the Harvard School of Public Health Center for Work, Health and Well-being, the Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (grant UL1 RR025758-04 from the National Center for Research Resources, and additional support was provided by Partners Occupational Health. OB was in part support by HL R01HL107240. This study would not have been accomplished without the participation of Partners HealthCare System and leadership from Dennis Colling, Sree Chaguturu, and Kurt Westerman. The authors would like to thank Partners Occupational Health Services including Marlene Freeley for her guidance, as well as Elizabeth Taylor, Elizabeth Tucker O’Day, and Terry Orechia. We also thank individuals at each of the hospitals including Jeanette Ives Erickson and Jacqueline Somerville in Patient Care Services leadership, and Jeff Davis and Julie Celano in Human Resources. Additionally, we wish to thank Charlene Feilteau, Mimi O’Connor, Margaret Shaw, Eddie Tan and Shari Weingarten for assistance with supporting databases. We also thank, Evan McEwing, Project Director, and Linnea Benson-Whelan for her assistance with the production of this manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None

References

- 1.Baglioni C, Riemann D. Is Chronic Insomnia a Precursor to Major Depression? Epidemiological and Biological Findings. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0308-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daley M, Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Grégoire JP, Savard J. The economic burden of insomnia: direct and indirect costs for individuals with insomnia syndrome, insomnia symptoms, and good sleepers. Sleep. 2009;32(1):55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buxton OM, Hopcia K, Sembajwe G, Porter JH, Dennerlein JT, Kenwood C, et al. Relationship of Sleep Deficiency to Perceived Pain and Functional Limitations in Hospital Patient Care Workers. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2012;54(7):851–58. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31824e6913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knutson KL. Sociodemographic and cultural determinants of sleep deficiency: Implications for cardiometabolic disease risk. Social Science & Medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Léger D, Bayon V. Societal costs of insomnia. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2010;14(6):379–89. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Äkerstedt T, Wright KP., Jr Sleep loss and fatigue in shift work and shift work disorder. Sleep Medicine Clinics. 2009;4(2):257. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Havlovic SJ, Lau DC, Pinfield LT. Repercussions of work schedule congruence among full-time, part-time, and contingent nurses. Health Care Management Review. 2002;27(4):30. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200210000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim SS, Okechukwu CA, Buxton OM, Dennerlein JT, Boden LI, Hashimoto DM, et al. Association between work-family conflict and musculoskeletal pain among hospital patient care workers. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1002/ajim.22120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grzywacz JG, Frone MR, Brewer CS, Kovner CT. Quantifying work-family conflict among registered nurses. Research in Nursing & Health. 2006;29(5):414–26. doi: 10.1002/nur.20133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogers B, Ostendorf J. Occupational Health Nursing. Wiley Online Library; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International classification of sleep disorders, revised: Diagnostic and coding manual. Chicago, Illinois: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Coulouvrat C, Hajak G, Roth T, Shahly V, et al. Insomnia and the performance of US workers: results from the America insomnia survey. Sleep. 2011;34(9):1161. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buxton OM, Marcelli E. Short and long sleep are positively associated with obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease among adults in the United States. Social Science and Medicine. 2010;71(5):1027–36. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dew MA, Hoch CC, Buysse DJ, Monk TH, Begley AE, Houck PR, et al. Healthy older adults’ sleep predicts all-cause mortality at 4 to 19 years of follow-up. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003;65(1):63–73. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000039756.23250.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strine TW, Chapman DP. Associations of frequent sleep insufficiency with health-related quality of life and health behaviors. Sleep Medicine. 2005;6(1):23–27. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vandeputte M, de Weerd A. Sleep disorders and depressive feelings: a global survey with the Beck depression scale. Sleep Medicine. 2003;4(4):343–45. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(03)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Äkerstedt T. Psychosocial stress and impaired sleep. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. 2006;32(6):493–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhui KS, Dinos S, Stansfeld SA, White PD. A Synthesis of the Evidence for Managing Stress at Work: A Review of the Reviews Reporting on Anxiety, Depression, and Absenteeism. Journal of Environmental and Public Health. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/515874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karasek RA., Jr Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1979:285–308. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson JV, Hall EM. Job strain, work place social support, and cardiovascular disease: a cross-sectional study of a random sample of the Swedish working population. American Journal of Public Health. 1988;78(10):1336–42. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.10.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wall TD, Jackson PR, Mullarkey S, Parker SK. The demands-control model of job strain: A more specific test. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 2011;69(2):153–66. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butler A, Grzywacz J, Bass B, Linney K. Extending the demands-control model: A daily diary study of job characteristics, work-family conflict and work-family facilitation. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 2005;78(2):155–69. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bellavia GM, Frone MR. Work-family conflict. Handbook of work stress. 2005:113–47. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Byron K. A meta-analytic review of work-family conflict and its antecedents. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2005;67(2):169–98. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lapierre LM, Allen TD. Work-supportive family, family-supportive supervision, use of organizational benefits, and problem-focused coping: implications for work-family conflict and employee well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2006;11(2):169. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.11.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindfors P, Berntsson L, Lundberg U. Total workload as related to psychological well-being and symptoms in full-time employed female and male white-collar workers. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;13(2):131–37. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1302_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hill HD. Paid Sick Leave and Job Stability. Work and Occupations. 2013;40(2):143–73. doi: 10.1177/0730888413480893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eaton SC. If you can use them: Flexibility policies, organizational commitment, and perceived performance. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society. 2003;42(2):145–67. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lundberg U, Frankenhaeuser M. Stress and workload of men and women in high-ranking positions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 1999;4(2):142. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.4.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morin CM, Rodrigue S, Ivers H. Role of stress, arousal, and coping skills in primary insomnia. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003;65(2):259–67. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000030391.09558.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams A, Franche RL, Ibrahim S, Mustard CA, Layton FR. Examining the relationship between work-family spillover and sleep quality. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2006;11(1):27. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.11.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nylén L, Melin B, Laflamme L. Interference between work and outside-work demands relative to health: unwinding possibilities among full-time and part-time employees. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;14(4):229–36. doi: 10.1007/BF03002997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lallukka T, Rahkonen O, Lahelma E, Arber S. Sleep complaints in middle-aged women and men: the contribution of working conditions and work-family conflicts. Journal of Sleep Research. 2010;19(3):466–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2010.00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Netemeyer RG, Boles JS, McMurrian R. Development and validation of work-family conflict and family-work conflict scales. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1996;81(4):400. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karasek R, Brisson C, Kawakami N, Houtman I, Bongers P, Amick B. The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): an instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 1998;3(4):322. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.3.4.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Denson TF, Spanovic M, Miller N. Cognitive appraisals and emotions predict cortisol and immune responses: a meta-analysis of acute laboratory social stressors and emotion inductions. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(6):823. doi: 10.1037/a0016909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang NKY, Harvey AG. Effects of cognitive arousal and physiological arousal on sleep perception. Sleep. 2004;27(1):69–78. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barnes CM, Wagner DT, Ghumman S. Borrowing from Sleep to Pay Work and Family: Expanding Time-Based Conflict to the Broader Nonwork Domain. Personnel Psychology. 2012;65(4):789–819. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grandey AA, Cropanzano R. The conservation of resources model applied to work-family conflict and strain. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 1999;54(2):350–70. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buysse DJ, Angst J, Gamma A, Ajdacic V, Eich D, Rössler W. Prevalence, course, and comorbidity of insomnia and depression in young adults. Sleep. 2008;31(4):473. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.4.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Posternak MA, Solomon DA, Leon AC, Mueller TI, Shea MT, Endicott J, et al. The naturalistic course of unipolar major depression in the absence of somatic therapy. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194(5):324–29. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000217820.33841.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harvey AG, Murray G, Chandler RA, Soehner A. Sleep disturbance as transdiagnostic: Consideration of neurobiological mechanisms. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31(2):225–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]