Abstract

Rationale

Despite their chemical similarities, methamphetamine and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) produce differing neurochemical and behavioral responses in animals. In humans, individual studies of methamphetamine and MDMA indicate that the drugs engender overlapping and divergent effects; there are only limited data comparing the two drugs in the same individuals.

Objectives

This study examined the effects of methamphetamine and MDMA using a within-subject design.

Methods

Eleven adult volunteers completed this 13-day residential laboratory study, which consisted of four 3-day blocks of sessions. On the first day of each block, participants received oral methamphetamine (20, 40 mg), MDMA (100 mg), or placebo. Drug plasma concentrations, cardiovascular, subjective, and cognitive/psychomotor performance effects were assessed before drug administration and after. Food intake and sleep were also assessed. On subsequent days of each block, placebo was administered and residual effects were assessed.

Results

Acutely, both drugs increased cardiovascular measures and “positive” subjective effects and decreased food intake. In addition, when asked to identify each drug, participants had difficulty distinguishing between the amphetamines. The drugs also produced divergent effects: methamphetamine improved performance and disrupted sleep, while MDMA increased “negative” subjective-effect ratings. Few residual drug effects were noted for either drug.

Conclusions

It is possible that the differences observed could explain the differential public perception and abuse potential associated with these amphetamines. Alternatively, the route of administration by which the drugs are used recreationally might account for the many of the effects attributed to these drugs (i.e., MDMA is primarily used orally, whereas methamphetamine is used by routes associated with higher abuse potential).

Keywords: Methamphetamine, MDMA, Amphetamines, Psychomotor performance, Subjective effects, Sleep, Food intake, Humans

Introduction

The amphetamine analogs methamphetamine and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) are used in various social settings purportedly because they increase sociability, euphoria, and alertness (Halkitis et al. 2005; Kelly et al. 2006; Rodgers et al. 2006). Both amphetamines also produce other prototypical stimulant effects, including increased heart rate and blood pressure, decreased food intake, and sleep disruptions (e.g., Comer et al. 2001; Vollenweider et al. 1998). Despite many overlapping effects, methamphetamine and MDMA are commonly regarded as distinct. For example, an impressively large human literature suggests that methamphetamine produces particularly pernicious long-term effects, including cognitive impairments (e.g., Baicy and London 2007), tooth decay (i.e., “meth mouth”: e.g., Hamamoto and Rhodus 2009), and psychological disturbances (e.g., Grelotti et al. 2010). A comparable literature for MDMA does not exist. The MDMA literature concerning long-term cognitive deficits is characterized by conflicting results (see Lyvers 2006 for review). Some researchers have found persistent cognitive impairments in MDMA users (e.g., Bolla et al. 1998), while others have observed few differences between MDMA users and controls (e.g., Hoshi et al. 2007). On the other hand, some reports indicate that MDMA use produces unique effects that are unlike other amphetamines, such as a temporary depressive state colloquially referred to as “Suicide Tuesday” in the days following use (e.g., Parrott and Lasky 1998). It is possible that the route by which these drugs are most often used recreationally might account for some differences. Methamphetamine, for instance, is used via routes other than oral (e.g., smoked and intravenous), which increases the likelihood of abuse and other deleterious effects.

Another possible explanation is that the chemical structural variations between methamphetamine and its ring-substituted analog MDMA contribute to the purported divergent profiles. Indeed, there is empirical evidence indicating that these structural differences result in differing neurochemical responses. For instance, although both amphetamines release brain monoamines, the degrees to which they release these neurotransmitters vary depending upon the drug. That is, methamphetamine is a more potent releaser of dopamine (DA) and norepinephrine (NE), whereas MDMA is a more potent releaser of serotonin (5-HT; Rothman et al. 2001). It has been suggested that these neurochemical differences underlie some of the differing behavioral responses observed in laboratory animals. For example, in a study comparing the relative reinforcing effects of amphetamines in rhesus monkeys, Wang and Woolverton (2007) found that methamphetamine was a more potent reinforcer than MDMA and attributed this difference to the relatively greater dopamine to serotonin releasing potency of methamphetamine. Furthermore, Crean et al. (2006) reported that methamphetamine and MDMA produced differential effects on measures of locomotor activity and temperature regulation in rhesus monkeys. These researchers speculated the observed behavioral differences were due to the fact that the amphetamines differentially alter monoamine activity.

In humans, individual studies of methamphetamine and MDMA indicate that the drugs engender both overlapping and divergent effects. For example, both oral methamphetamine and MDMA increase wakefulness and euphoria and decrease food intake (e.g., Cami et al. 2000; Hart et al. 2002, 2003; Liechti et al. 2001; Tancer and Johanson 2003). Although methamphetamine improves some measures of cognitive performance (e.g., Hart et al. 2002; Silber et al. 2006), MDMA does not and, in some cases, disrupts cognitive performance (e.g., Cami et al. 2000; Kuypers and Ramaekers 2005). Only a limited number of studies have compared the direct effects amphetamines with MDMA in the same research participants (Cami et al. 2000; Tancer and Johanson 2003; Johanson et al. 2006; Bedi et al. 2010). In general, the drugs had a profile of behavioral, physiological, and subjective effects that overlapped, although some differences were observed.

In an effort to expand upon the dearth of studies examining this issue, the present investigation directly compared the acute and residual effects of methamphetamine (20 and 40 mg) and MDMA (100 mg) using a within-subjects design. We have previously published a subset of data from this study focused on speech (Marrone et al. 2010). The purpose of this larger study was to assess the effects of the two amphetamines on a wider set of behaviors including, cognitive/psychomotor performance, mood, food intake, physiological measures, and sleep. We hypothesized that: (1) acute methamphetamine and MDMA would similarly increase “positive” ratings of mood; (2) methamphetamine would improve measures of cognitive/psychomotor performance; and (3) MDMA would decrease measures of cognitive/psychomotor performance. We also predicted that both drugs would decrease sleep and that MDMA would disrupt mood in the days following drug administration.

Methods and materials

Participants

Eleven research volunteers (mean age 29.3±5.0 [±SD]) completed this 13-day inpatient study. Two participants were female (one Black, one Hispanic) and nine were male (one Asian, two Black, two Hispanic, four White). They were recruited via word-of-mouth referral and newspaper and online advertisement in New York City. On average, they had completed 14.1±1.5 (mean ± SD) years of formal education. All passed comprehensive medical examinations and psychiatric interviews and were within normal weight ranges according to the 1983 Metropolitan Life Insurance Company height/weight table (body mass index: 24.9±1.2 [mean ± SD]). All participants reported previous experience with methamphetamine and MDMA. Six participants reported current smoked and intranasal methamphetamine use 4.2±4.7 days/month and ten reported current oral MDMA use 2.1±1.8 days/month. Four participants reported current cocaine use (1–4 days/month), nine reported current alcohol use (1–3 days/week), nine reported current marijuana use (1–7 days/week), and eight smoked 1–10 tobacco cigarettes/day. No participant met criteria for an Axis I disorder and no one was seeking treatment for her/his drug use.

Before study enrollment, each signed a consent form that was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The New York State Psychiatric Institute (NYSPI). Upon discharge, each participant was informed about experimental and drug conditions and was paid for their participation. They were compensated at a rate of $35/day; those who completed the entire 13-day study were paid an additional bonus of $35/day.

Pre-study training

Prior to starting the study, participants completed two training sessions (3–4 h each) on the computerized cognitive/psychomotor tasks that would be used during the study. Additionally, on a separate day, they received the largest methamphetamine dose (40 mg) to be tested inpatient in order to monitor any adverse reactions and provide them with experience with a study drug in the laboratory setting. Participants were not informed of the drug or dose until study debriefing.

Design

Participants were housed in a residential laboratory at the NYSPI in three groups of three to four individuals. The study consisted of one acclimation day followed by four 3-day blocks of sessions, during which participants completed visual analog mood scales and cognitive/psychomotor task batteries. On the first day of each block, participants were administered either placebo or active drug capsules. The dosing order was counterbalanced so that no two participants received the same drug on the same day. On days 2 and 3 of each block, participants were administered placebo capsules. These days served as washout a period and provided the opportunity to investigate residual drug effects.

Procedure

Participants moved into the laboratory on the day before the study began so that they could receive further training on tasks and experimental procedures. The first experimental day began the following morning at 0800 hours. Table 1 displays experimental session activities. Fifteen minutes after awakening at 0815 hours, participants completed a visual analog sleep questionnaire and the baseline task battery, composed of the cognitive/psychomotor tasks and the subjective-effects questionnaire (described below). Then, they were weighed (but were not informed of their weight) and given time to eat breakfast. Following breakfast at 0945 hours, participants were administered an active drug capsule or placebo in a private vestibule. Then, participants completed two task batteries from 1045 to 1245 hours, took a 1.5-h lunch break period, and completed three additional task batteries from 1415 to 1700 hours. Participants were given a 15-min break between each task battery. Cardiovascular measures and oral temperature were obtained at baseline and 0.5, 1.5, 3, 6.25, and 7.25 h after capsule administration. Blood samples were collected at baseline and 0.5, 1.5, 3, and 6.25 h after capsule administration on the first day of each block via an i.v. line, which was kept patent by a physiological saline solution drip. An additional blood sample was obtained 24 h after capsule administration.

Table 1. Typical experimental day.

| Time | Activity |

|---|---|

| 0815 | Sleep questionnaire |

| Cardiovascular measures | |

| Task battery 1 | |

| 0945 | Drug administration |

| 1015 | Cardiovascular measures |

| 1045 | Task battery 2 |

| 1115 | Cardiovascular measures |

| 1215 | Task battery 3 |

| 1245 | Cardiovascular measures |

| 1245–1415 | Lunch break period |

| 1430 | Task battery 4 |

| 1515 | Task battery 5 |

| 1600 | Cardiovascular measures |

| 1630 | Task battery 6 |

| Cardiovascular measures | |

| 1715–2330 | Social period |

| 2400 | Lights Out |

Each task battery was comprised of the cognitive/psychomotor tasks and subjective-effects questionnaires

Beginning at 1715 hours, participants had access to the social area, where they could interact with other study participants and engage in recreational activities. Two films were shown daily, beginning at 1730 and 2030 hours. During this period, social behavior was recorded using a computerized observation program that prompted recording of each participant's behavior every 2.5 min (e.g., Haney et al. 2007). Behaviors were classified into private (time spent in bathroom/bedroom) and social (time spent in the recreational area). Time spent in the social area was further divided into time spent talking and time spent in silence. Outcomes were total minutes spent engaging in each behavior per day. Lights were turned out at 2400 hours for an 8-h sleep period. Participants could smoke cigarettes ad libitum from 0800 to 2300 hours.

Subjective-effects and psychomotor battery

The computerized visual analog questionnaire consisted of a series of 100-mm lines labeled “not at all” at one end and “extremely” at the other end (Hart et al. 2003). The lines were labeled with adjectives describing a mood (e.g., “I feel…,” “irritable,” “talkative,” “unmotivated”), a drug effect (e.g., “I feel…,” “stimulated,” “a good drug effect,” “a bad drug effect”), or a physical symptom (“I feel nauseous,” “I have a headache,” “My heart is beating faster than usual”). Additionally, at various time points participants completed a drug-effect questionnaire (DEQ), during which they were required to rate “good effects” and “bad effects” on a 5-point scale: 0 =“not at all” and 4=“very much.” They were also asked to rate the drug strength as well as their desire “to take the drug again.” Lastly, participants were asked to rate how much they liked the drug effect on a 9-point scale: -4=“disliked very much,” 0=“feel neutral, or feel no drug effect,” and 4=“liked very much.” At the end of the final task battery at 1715 hours, participants completed a final two-item questionnaire during which they were required to (1) write which drug they thought they had received and (2) rate their confidence about this judgment on a 100-mm line labeled “not at all” at one end and “extremely” at the other end.

The computerized psychomotor task battery consisted of five tasks: (1) the Digit Recall Task, designed to assess changes in immediate and delayed recall (see Hart et al. 2001); (2) the digit-symbol substitution task (DSST), designed to assess changes in visuospatial processing (McLeod et al. 1982); (3) the divided attention task (DAT), designed to assess changes in vigilance and inhibitory control (Miller et al. 1988); (4) the rapid information task (RIT), designed to assess changes in sustained concentration and inhibitory control (Wesnes and Warburton 1983); and (5) the Repeated Acquisition Task, designed to assess changes in learning and memory (Kelly et al. 1993).

Food monitoring

Food items were available ad libitum from 0845 to 2330 hours, and water was available at all times. Meals that required preparation time (e.g., frozen meals) were not permitted while completing task batteries. Consumption of food items was closely examined. Participants were required to specify the substance and portion of any item they ate or drank by scanning custom-designed barcodes and were informed that independent observers would continuously monitor their food intake. Research monitors in the control room electronically acknowledged and kept hand-written records of each food request and report. Moreover, wrappers for each food item were color-coded by participant and their trash was examined daily to confirm the accuracy of their reports and of the observers' records. These procedures do not alter total daily intake and are sensitive to methodologies influencing amounts and patterns of intake (Foltin et al. 1988, 1992; Haney et al. 1997; Perez et al. 2008a).

Sleep monitoring

Objective sleep was measured by tracking gross motor activity using the Actiwatch® Activity Monitoring System (Actiwatch®; Respironics Company, Bend, OR). This system allowed for calculation of total sleep time, sleep onset latency, sleep efficiency (total sleep time as a percentage of time in bed), and number of wake bouts (Kushida et al. 2001). Subjective sleep experience from the immediately preceding sleep period was measured by a visual analog sleep questionnaire completed shortly after waking. The questionnaire consisted of a series of 100mm lines labeled “not at all” at one end and “extremely” at the other end. The lines were labeled: “I slept well last night,” “I woke up early this morning,” “I fell asleep easily last night,” “I feel clear-headed this morning,” “I woke up often last night,” “I am satisfied with my sleep last night,” and a fill-in question in which participants were asked to estimate the number of hours they slept the previous night (Haney et al. 2001).

Drug

Tablets of methamphetamine hydrochloride (MA; Desoxyn, Abbot Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) and MDMA hydrochloride (manufactured and provided by Dr. David Nichols of Purdue University) were repackaged by the Pharmacy Department of the NYSPI by placing tablets into a white no. 00 opaque capsule and adding lactose filler. Placebo consisted of white no. 00 capsules containing only lactose. The drug doses examined were based on previous separate studies suggesting that 40 mg methamphetamine and 100 mg MDMA produce similar effects on cardiovascular measures and “positive” subjective ratings of mood (Hart et al. 2002, 2008, in preparation). Briefly, Hart and colleagues (in preparation) examined the effects of oral MDMA (0, 50, 100 mg) and data from that study suggested that the 100-mg MDMA dose would produce greater effects than 20 mg methamphetamine (oral; Hart et al. 2002) but similar effects to 40 mg methamphetamine (oral; Hart et al. 2008). The 20-mg methamphetamine dose was included here to provide information about the methamphetamine dose response curve. A lower MDMA dose (i.e., 50 mg) was not included because this dose produced subjective effects similar to 100 mg MDMA (Hart et al., in preparation) and it would have increased the study length, increasing the likelihood of participant dropout.

Data analysis

Cardiovascular effects, drug plasma concentrations, subjective ratings, food intake, and cognitive/psychomotor performance data were analyzed using a two-factor repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVA): the first factor was drug condition (placebo, 20 mg and 40 mg methamphetamine, and 100 mg MDMA) and the second factor was time of assessment (timing and number of assessments varied depending on the measure, e.g., subjective ratings were assessed at time points baseline, 1.0, 2.5, 4.75, 5.5, and 6.75 h after capsule administration). Peak cardiovascular and subjective-effects data were also analyzed; for the sake of brevity, these analyses are included in Table 2 only. Cigarette consumption, social interaction measures, and sleep data were analyzed using a single-factor ANOVA; the factor was drug condition. For all analyses, ANOVAs provided the error terms needed to calculate the following planned comparisons: placebo vs. all active doses, 20 mg vs. 40 mg MA, 20 mg MA vs. 100 mg MDMA, and 40 mg MA vs. 100 mg MDMA. p values were considered statistically significant at less than 0.05, using Huynh– Feldt corrections when appropriate.

Table 2. Acute (day 1) amphetamine-related effects on subjective-effect ratings.

| Drug conditions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Placebo | 20 mg MA | 40 mg MA | 100 mg MDMA | ||||

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Mean (SEM) | Mean (SEM) | F value | Mean (SEM) | F value | Mean (SEM) | F value | |

| Peak physiological and “positive” subjective-effect ratings | |||||||

| Alert | 28.0 (9.1) | 55.3 (9.6) | 18.2* | 61.5 (9.2) | 27.6* | 34.6 (9.0) | 10.4§† |

| Blurred vision | 0.0 (0.0) | 3.2 (2.5) | 1.1 | 6.5 (3.7) | 4.7 | 27.2 (9.8) | 81.8*§† |

| Chills | 0.0 (0.0) | 1.7 (1.7) | 0.3 | 2.1 (1.8) | 0.5 | 17.7 (9.7) | 32.3*§† |

| Content | 43.5 (10.5) | 52.9 (9.0) | 1.6 | 64.8 (10.0) | 8.3* | 49.4 (7.9) | 0.6 |

| Energetic | 26.0 (8.9) | 51.6 (8.5) | 17.0* | 53.3 (8.9) | 19.3* | 24.9 (7.6) | 18.5§† |

| Good drug effect | 2.3 (2.3) | 31.7 (10.3) | 38.1* | 55.8 (10.9) | 125.9* | 49.6 (11.6) | 98.5*§ |

| Heart pounding | 2.9 (2.9) | 16.8 (8.7) | 13.2* | 22.4 (10.4) | 25.8* | 20.9 (9.9) | 22.1* |

| High | 3.0 (2.7) | 37.4 (10.1) | 72.2* | 51.9 (8.5) | 146.2*§ | 62.1 (10.8) | 213.5*§† |

| Social | 38.6 (8.7) | 57.2 (6.8) | 12.8* | 53.5 (7.8) | 8.3* | 41.2 (9.9) | 9.5§† |

| Stimulated | 8.2 (4.1) | 40.5 (8.6) | 62.5* | 54.4 (6.1) | 127.4*§ | 45.5 (11.1) | 83.4* |

| Sweating | 0.0 (0.0) | 8.6 (5.0) | 5.0 | 19.8 (9.0) | 26.6*§ | 32.3 (12.4) | 70.4*§ † |

| Talkative | 31.7 (10.5) | 34.2 (10.8) | 0.1 | 49.5 (8.5) | 7.6*§ | 27.5 (8.6) | 11.6† |

| Want cigarette | 10.7 (5.2) | 25.2 (11.0) | 3.8 | 19.4 (7.9) | 1.3 | 31.2 (10.9) | 7.6* |

| Peak “negative” subjective-effect ratings | |||||||

| Bad drug effect | 1.1 (1.1) | 6.6 (4.8) | 3.1 | 0.4 (0.4) | 0.1 | 20.9 (8.4) | 39.1*§† |

| Can't concentrate | 10.7 (8.0) | 6.4 (6.0) | 0.5 | 13.6 (6.7) | 0.2 | 34.6 (10.4) | 14.9*§† |

| Clumsy | 2.1 (1.8) | 5.3 (4.7) | 0.8 | 6.2 (5.8) | 1.2 | 21.3 (9.6) | 27.1*§† |

| Confused | 5.5 (3.2) | 6.4 (6.1) | 0.0 | 9.5 (6.4) | 1.2 | 21.3 (8.9) | 18.3*§† |

| Dizzy | 2.9 (2.9) | 4.8 (4.0) | 0.3 | 5.9 (5.2) | 0.8 | 26.4 (11.1) | 49.7*§† |

| Jittery | 1.6 (2.6) | 13.8 (7.6) | 13.9* | 8.0 (3.8) | 3.8 | 34.2 (10.0) | 99.2*§† |

| Nauseous | 2.5 (2.1) | 1.5 (1.5) | 0.1 | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.7 | 15.1 (8.2) | 17.0*§† |

| Restless | 11.6 (7.2) | 17.5 (9.2) | 1.4 | 9.6 (6.9) | 0.2 | 24.5 (10.9) | 6.6*† |

| Sedated | 0.9 (0.9) | 2.8 (2.5) | 0.2 | 5.8 (5.8) | 1.4 | 26.9 (10.5) | 38.9*§† |

p<0.05, significantly different from placebo

p<0.05, significantly different from 20 mg MA

p<0.05, significantly different from 40 mg MA

Results

Plasma methamphetamine and MDMA levels

Acute effects

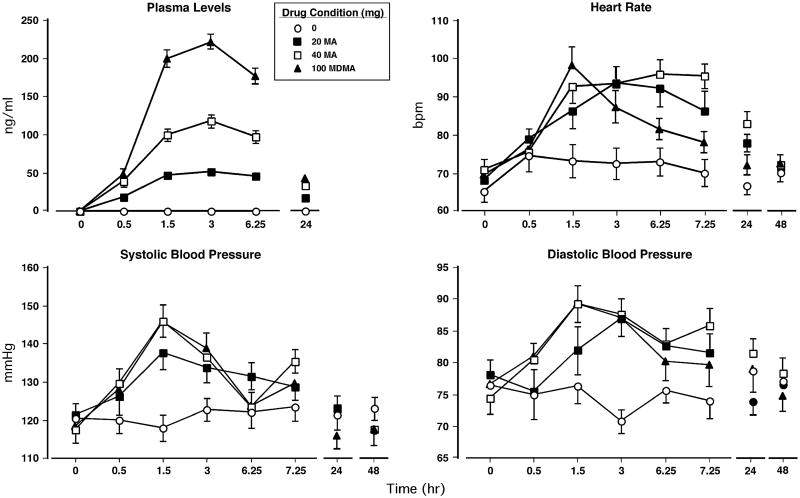

Figure 1 (top left panel) shows that methamphetamine (20 and 40 mg) and MDMA increased drug plasma concentrations. Peak plasma concentrations for each drug were observed 3 h after drug administration and declined over the next several hours. The effect of methamphetamine was dose-related in that both doses caused a significantly greater concentration increase than placebo and that the 40-mg dose produced larger increases than the 20-mg dose (p<0.0001 for all comparisons).

Fig. 1.

Upper panel (left): the administered drug plasma levels as a function of drug dose and time. Upper panel (right): heart rate as a function of drug dose and time. Lower panels: systolic and diastolic pressure as a function of drug dose and time. Error bars represent 1 SEM. Overlapping error bars were omitted for clarity

Residual effects

Although methamphetamine and MDMA plasma concentrations steadily declined over the 24-h post drug administration, they remained significantly elevated compared to predrug administration levels.

Cardiovascular and oral temperature effects

Acute effects

Figure 1 (top right and bottom panels) displays cardiovascular measures as a function of dosing condition and time. Peak cardiovascular effects occurred between 90 and 180 min. Relative to placebo, active drug conditions significantly increased heart rate (HR), systolic pressure (SP), and diastolic pressure (DP: p<0.0001 for all comparisons). When active dosing conditions were compared, the 40-mg methamphetamine dose produced greater sustained HR increases than MDMA (p<0.01) and larger SP and DP elevations than the 20-mg methamphetamine dose (p<0.01). There were no significant drug effects on oral temperature.

Residual effects

Both methamphetamine doses caused HR to remain significantly increased 24 h after their administration compared to placebo (p<0.01). In addition, relative to MDMA, 40 mg methamphetamine produced significantly elevated HR and DP 24 h after drug administration (p<0.01)

Subjective effects

Acute effects

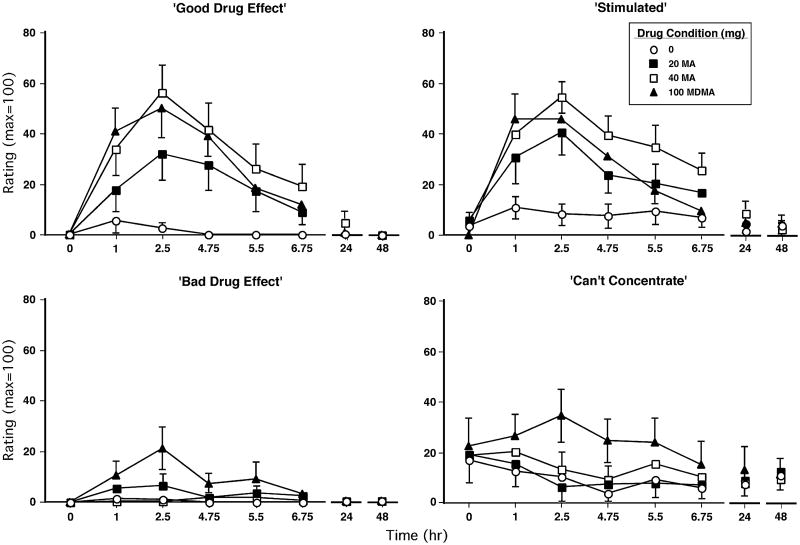

Figure 2 illustrates the effects of dosing condition on selected subjective-effect ratings over time. Relative to placebo, methamphetamine (20 and 40 mg) and MDMA markedly increased ratings of “good drug effect” and “stimulated” (p<0.03 for all comparisons). Both the larger methamphetamine dose (40 mg) and MDMA produced greater ratings of “good drug effect” than the lower methamphetamine dose (20 mg); the 40-mg methamphetamine dose significantly elevated ratings of “stimulated” compared to the 20-mg dose and MDMA (p<0.03 for all comparisons). MDMA produced significantly greater ratings of “bad drug effect,” “can't concentrate,” “tired,” and “sleepy” than placebo and both methamphetamine doses (p<0.05 for all comparisons; some data not shown). In general, peak subjective-effect ratings for both drugs were observed approximately 2.5 h after drug administration; statistically significant effects are summarized in Table 2.

Fig. 2.

Selected subjective-effect ratings as a function of drug dose and time. Error bars represent 1 SEM. Overlapping error bars were omitted for clarity

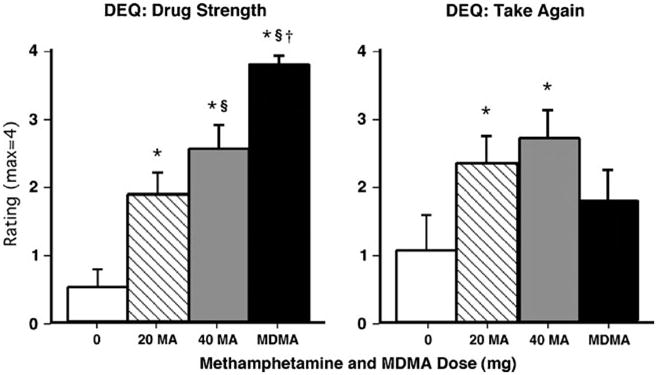

Figure 3 (left panel) shows that methamphetamine and MDMA significantly increased peak DEQ ratings of “drug strength” and “good drug effect” compared to placebo (p<0.0001 for all comparisons; some data not shown). However, only methamphetamine (20 mg and 40 mg) significantly increased participants' reported desire to take the drug again (p<0.03; Figure 3, right panel) and ratings of “drug liking” (p<0.05); conversely, only MDMA significantly increased DEQ ratings of “bad drug effect” (p<0.01).

Fig. 3.

Selected peak DEQ ratings as a function of drug dose. Error bars represent one SEM. *Significantly different from placebo (p<0.05). §Significantly different from 20 mg methamphetamine (p<0.05). †Significantly different from 40 mg methamphetamine (p<0.05)

On the questionnaire probing what drug the participants thought they had received, 72.7% of participants (i.e., eight out of 11) correctly identified placebo (18.2% reported MDMA and 9.1% reported sedative; confidence rating= 72.7±9.5), 45.5% correctly identified 20 mg methamphetamine (45.5% reported MDMA and 9.1% reported placebo; confidence rating=76.7±13.3), 72.7% correctly identified 40 mg methamphetamine (27.3% reported MDMA; confidence rating=80.1±5.6), and 45.5% correctly identified 100 mg MDMA (27.3% reported methamphetamine and 27.3% reported sedative; confidence rating=87.6±5.2).

Residual effects

Relative to placebo, under the 40-mg methamphetamine dose condition, ratings of “tired” were significantly elevated 24 h after drug administration (19.4±3.4 [placebo] vs. 33.8±3.9 [40 mg MA], p<0.05). No other significant subjective effects were observed on days 2–3.

Cognitive/psychomotor performance effects

Acute effects

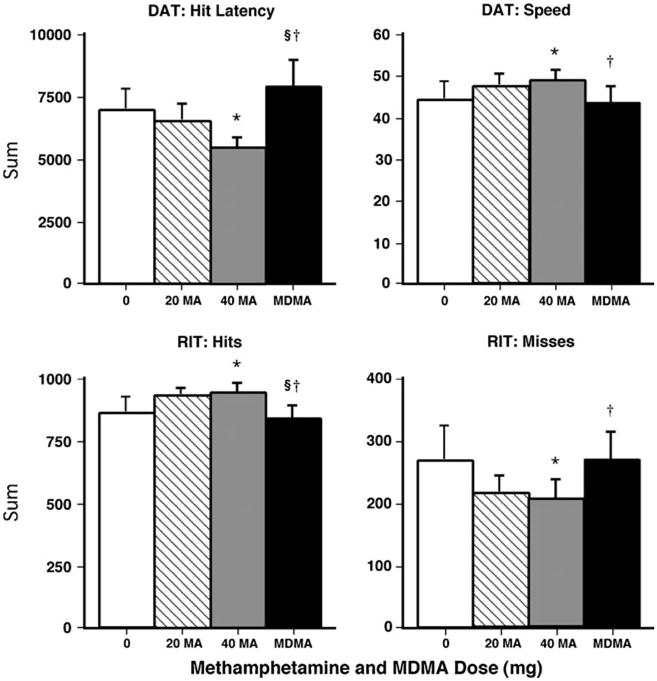

Figure 4 shows that the 40-mg methamphetamine dose improved performance over the course of the session on the DAT and RIT. Regarding the DAT, methamphetamine decreased mean hit latency and increased maximum tracking speed compared to placebo and MDMA (p<0.05 for both comparisons). On the RIT, methamphetamine increased the total number of hits and decreased the number of misses compared to placebo and MDMA (p<0.05 for both comparisons). MDMA did not significantly alter cognitive/psychomotor performance.

Fig. 4.

Selected cognitive/psychomotor performance effects (summed across the session) as a function of drug dose. Error bars represent 1 SEM. *Significantly different from placebo (p<0.05). §Significantly different from 20 mg methamphetamine (p<0.05). †Significantly different from 40 mg methamphetamine (p<0.05)

Residual effects

Day 2 performance on the RIT remained improved under the 40-mg methamphetamine condition compared to placebo. Hits were significantly increased and misses were significantly decreased (p<0.05). No other significant performance effects were noted.

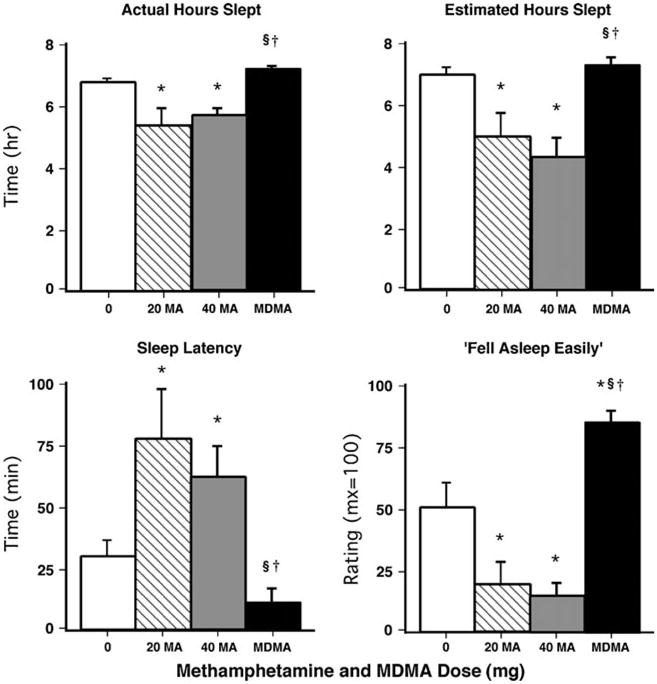

Sleep effects

Residual effects

Figure 5 illustrates the effects of dosing condition on sleep during the sleep period that began 14.25 h after drug administration. Relative to placebo and MDMA, methamphetamine reduced both the objective and subjective number of hours participants slept (p<0.001). This effect appeared to be partially mediated by methamphetamine-related actions on sleep onset latency: under both methamphetamine conditions, objective measures of onset latency were increased and participants reported greater difficulty falling asleep (p<0.005 for all comparisons). Conversely, ratings of “fell asleep easily” were significantly increased by MDMA compared to placebo (p<0.001). Table 3 shows additional significant effects produced by methamphetamine and MDMA on objective and subjective sleep measures on day 1 (i.e., 14.25 h after drug administration).

Fig. 5.

Left panels: selected objective sleep measures on day 1 (i.e., 14.25 h after drug administration) as a function of drug dose. Right panels: selected subjective sleep measures on day 1 (i.e., 14.25 h after drug administration) as a function of drug dose. Error bars represent 1 SEM. *Significantly different from placebo (p<0.05). §Significantly different from 20 mg methamphetamine (p<0.05). †Significantly different from 40 mg methamphetamine (p<0.05)

Table 3. Amphetamine-related effects on sleep measures and food intake (day and night 1).

| Drug conditions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Placebo | 20 mg MA | 40 mg MA | 100 mg MDMA | ||||

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Mean (SEM) | Mean (SEM) | F value | Mean (SEM) | F value | Mean (SEM) | F value | |

| Sleep questionnaire (measurements from night 1) | |||||||

| Slept well | 63.6 (5.9) | 36.9 (10.3) | 11.2* | 41.4 (10.1) | 7.8* | 73.9 (6.3) | 21.5§† |

| Woke often | 32.5 (8.5) | 47.7 (10.2) | 3.4 | 53.8 (9.8) | 6.7* | 18.2 (7.8) | 13.0§† |

| Satisfied with sleep | 57.9 (6.8) | 33.4 (8.9) | 9.4* | 34.5 (9.3) | 8.6* | 65.5 (9.0) | 16.1§† |

| Woke early | 41.3 (9.3) | 44.1 (11.3) | 0.1 | 63.5 (13.5) | 4.1 | 19.4 (6.3) | 5.1§† |

| Actiwatch measures (measurements from night 1) | |||||||

| Sleep efficiency (%) | 84.9 (1.8) | 67.4 (7.1) | 32.9* | 71.6 (2.9) | 19.2* | 90.3 (1.2) | 56.7§† |

| # of awakenings per hour | 2.9 (0.3) | 2.6 (0.3) | 0.8 | 3.8 (0.4) | 9.0*§ | 2.7 (0.3) | 6.2† |

| Awakenings duration (min) | 1.7 (0.2) | 1.7 (0.1) | 0.0 | 2.1 (0.2) | 8.7*§ | 1.4 (0.1) | 23.4† |

| Food intake (measurements from day 1) | |||||||

| Total # of eating occasions | 10.1 (1.0) | 5.7 (0.7) | 34.6* | 5.5 (0.6) | 37.5* | 7.5 (0.9) | 12.6*§† |

| Protein | |||||||

| Total consumed (g) | 94.5 (6.5) | 41.8 (7.4) | 73.4* | 40.2 (8.1) | 77.8* | 56.6 (5.5) | 37.9*§† |

| Prop. of total calories (%) | 12.5 (0.9) | 11.4 (2.1) | 1.7 | 11.1 (1.5) | 2.9 | 10.8 (1.2) | 4.3 |

| Carbohydrates | |||||||

| Total consumed (g) | 448.4 (53.6) | 262.6 (36.1) | 38.8* | 244.3 (37.6) | 44.4* | 341.3 (45.8) | 12.2*§† |

| Prop. of total calories (%) | 54.9 (2.0) | 65.9 (4.7) | 14.9* | 66.1 (4.0) | 15.4* | 59.1 (2.6) | 5.9§† |

| Fat | |||||||

| Total consumed (g) | 121.0 (17.7) | 36.3 (5.3) | 47.4* | 45.1 (15.0) | 38.1* | 76.9 (10.4) | 12.9*§† |

| Prop. of total calories (%) | 32.6 (2.5) | 22.7 (3.3) | 14.7* | 22.9 (3.1) | 14.2* | 30.1 (3.0) | 8.3§† |

p<0.05, significantly different from placebo

p<0.05, significantly different from 20 mg MA

p<0.05, significantly different from 40 mg MA

Table 4 shows that several objective and subjective sleep measures were altered on day 2. For example, relative to placebo, the 40-mg methamphetamine dose significantly increased the actual number of hours slept on day 2 (p<0.05).

Table 4. Amphetamine-related effects on sleep measures (night 2).

| Drug conditions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Placebo | 20 mg MA | 40 mg MA | 100 mg MDMA | ||||

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Mean (SEM) | Mean (SEM) | F value | Mean (SEM) | F value | Mean (SEM) | F value | |

| Actiwatch measures (measurements from night 2) | |||||||

| Actual time slept (h) | 6.5 (0.3) | 6.4 (0.3) | 0.2 | 7.1 (0.1) | 6.3* | 7.0 (0.1) | 3.6 |

| Sleep latency (min) | 53.0 (15.6) | 55.6 (18.5) | 0.1 | 13.7 (4.9) | 16.5* | 18.9 (3.3) | 12.4* |

| Sleep efficiency (%) | 81.7 (3.2) | 80.3 (3.9) | 0.2 | 89.4 (1.5) | 6.3* | 87.5 (1.2) | 3.6 |

| Sleep questionnaire (measurements from night 2) | |||||||

| Estimated time slept | 6.2 (0.4) | 6.9 (0.3) | 2.9 | 7.1 (0.2) | 5.1* | 7.1 (0.2) | 6.0* |

| Fell asleep easily | 39.2 (10.3) | 62.6 (11.5) | 6.0* | 73.8 (4.8) | 13.1* | 52.6 (11.3) | 2.0 |

| Satisfied with sleep | 42.7 (8.6) | 61.8 (10.8) | 5.7* | 61.3 (9.2) | 5.4* | 61.6 (8.5) | 5.6* |

| Slept well | 46.5 (10.2) | 67.3 (7.7) | 6.7* | 68.5 (5.2) | 7.6* | 73.0 (4.8) | 11.0* |

p<0.05, significantly different from placebo

p<0.05, significantly different from 20 mg MA

p<0.05, significantly different from 40 mg MA

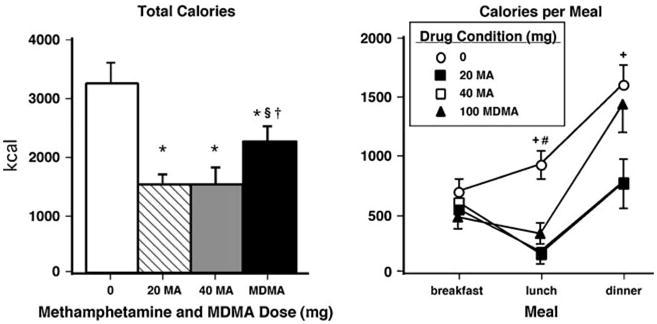

Effects on food intake

Acute effects

Relative to placebo, over the course of the entire day, both methamphetamine and MDMA significantly decreased the total number of calories consumed (Fig. 6, left panel). Both methamphetamine doses produced significantly greater reductions compared to MDMA (p<0.05 for all comparisons). Figure 6 (right panel) illustrates that this effect was mediated by methamphet-amine's longer duration of action. During “lunch” (i.e., 1015–1415 hours), both methamphetamine and MDMA decreased calories consumed compared to placebo. During “dinner” (i.e., 1415–2330 hours), however, only methamphetamine sustained a significant reduction in calorie consumption (p<0.005 for all comparisons). Table 3 shows additional significant effects produced by methamphetamine and MDMA on food intake measures.

Fig. 6.

Right panels: total number of calories consumed as a function of dose. Error bars represent 1 SEM. *Significantly different from placebo (p<0.05). §Significantly different from 20 mg methamphetamine (p<0.05). †Significantly different from 40 mg methamphetamine (p<0.05). Left panel: calories consumed as a function of drug dose and meal time (“breakfast”=0800-1015 hours, “lunch”=1015-1415 hours, “dinner”= 1415-2330 hours). Error bars represent 1 SEM. +Significantly different from 40 mg methamphetamine (p<0.05). #Significantly different from 100 mg MDMA (p<0.05)

Residual effects

There were no significant residual drug effects on food intake.

Effects on cigarette smoking

Acute effects

For the eight participants who smoked cigarettes during the study, both methamphetamine doses increased the number of cigarettes smoked compared to placebo (p<0.01); the average increase was approximately five to six cigarettes (7.4±1.4 [placebo] vs. 13.8±2.6 [20 mg MA], 12.4±2.2 [40 mg MA], and 10.4± 1.7 [100 mg MDMA]).

Residual effects

No significant residual drug effects on cigarette consumption were noted.

Effects on social interactions

There were no significant differences between doses on any measure of social interaction.

Discussion

The present findings show that acute single oral doses of methamphetamine and MDMA produced many overlapping, prototypical stimulant effects in experienced users of both drugs. Both amphetamines enhanced cardiovascular activity, increased ratings of stimulation, euphoria and mood, and decreased food intake. The drugs did, however, produce different acute effects on some measures. For example, only methamphetamine improved cognitive/psychomotor performance, increased participants' reported desire to take the drug again, and disrupted sleep. In addition, MDMA increased some measures of “negative” mood, while methamphetamine enhanced only “positive” mood ratings. In general, these results are consistent with previous studies that have compared the acute effects of oral amphetamines with MDMA (e.g., Tancer and Johanson 2003; Johanson et al. 2006; Bedi et al. 2010). The current study extends earlier findings by providing the first data directly comparing the residual effects of the two drugs in the same individuals.

An intriguing observation was that participants had difficulty distinguishing the amphetamines (i.e., many reported that methamphetamine was MDMA and vice versa), further indicating that the two drugs have similar effect profiles. This finding was unexpected because all study participants had previous experience with both methamphetamine and MDMA. In addition, there are scientific and popular reports suggesting that the two amphetamines produce largely distinct effects (e.g., Peroutka etal. 1988; Tancer and Johanson 2001; Holland 2001). One possible explanation for the current finding is the route by which the drugs were administered in the present study, i.e., both drugs were administered via the oral route. While MDMA is primarily taken orally, recreational methamphetamine is mainly used via routes other than oral such as the intranasal, intravenous, or smoked route (e.g., Simon et al. 2002). The route of administration difference can directly impact several aspects of acute drug actions. As we observed here, the onset of peak cardiovascular and subjective effects occurred approximately 1.5–2.5 h after oral methamphetamine administration. By contrast, we previously reported that comparable doses of intranasal methamphetamine produced peak effects within 15 min (Hart et al. 2008). Considering that the rapidity of drug-related effects is a crucial determinant of the intensity of mood and behavioral effects, as well as the abuse potential, of a drug (e.g., de Wit et al. 1993; Hatsukami and Fischman 1996), it is possible that participants would have experienced less difficulty discerning methamphetamine if it was administered by a route other than oral. Another possible explanation for this apparent incongruent finding is that the purity of some illicit MDMA can be relatively low and often contains other stimulants such as D-amphetamine and methamphetamine (Parrot 2004). Such previous drug experiences could have influenced the current results.

Despite the fact that most participants were unable to correctly identify the drug administered, methamphetamine and MDMA produced differences on some measures. For example, methamphetamine improved performance on tasks measuring response time and vigilance, while MDMA had no effect on performance. The finding that methamphetamine improved performance is consistent with our prediction and a growing database demonstrating enhanced performance on relatively simple tasks (Mohs et al. 1978; Hart et al. 2002; Silber et al. 2006). Although we did not observe support for the hypothesis that MDMA would disrupt performance, data from our earlier report showed that the drug caused verbal fluency decrements on a speech task completed 90 min after drug administration (Marrone et al. 2010). The amphetamines also engendered different effects on some “negative” mood ratings (e.g., only MDMA increased ratings of “bad drug effect” and “can't concentrate”). This point highlights a potential drawback of the present study — only one MDMA dose was examined. The MDMA dose tested was selected because it is within the range used by recreational users to produce desired effects (e.g., euphoria), but a more comprehensive understanding of the effects of this drug on human behavior, in comparison to methamphetamine, would require a wider range of doses.

Nevertheless, the observed differential effects on cognitive performance and mood might provide insight into the relative abuse potential of methamphetamine and MDMA. The fact that methamphetamine produced primarily “positive” psychological effects (i.e., mood and cognitive performance) might contribute to or enhance its abuse potential. Indeed, data from numerous studies indicate that the reinforcing effects of stimulants are increased when performance is perceived to be improved following drug administration (Silverman et al. 1994a, b; Comer et al. 1996; Jones et al. 2001; Stoops et al. 2005a, b). Conversely, the lack of performance improvements combined with some acute “negative” mood effects following MDMA administration may limit its abuse potential compared to methamphetamine. Consistent with this speculation is the current finding that only methamphetamine (and not MDMA) increased participants' reported desire to take the drug again. Subjective, performance, and reinforcing effects are dissociable, of course, and, as a result, future studies should directly examine the relative reinforcing effects of methamphetamine and MDMA in humans.

With regards to residual drug effects, only methamphetamine disrupted sleep, as assessed by both objective and subjective measures. It is noteworthy that a single oral methamphetamine dose administered 14.25 h prior to bedtime decreased sleep in experienced methamphetamine users. Consequently, participants reported being markedly more tired on the day following methamphetamine administration. These results are in agreement with our prior findings investigating the effects of intranasal and repeated oral doses of methamphetamine on sleep (Perez et al. 2008b; Comer et al. 2001). In contrast, MDMA did not produce any sleep disturbances. In fact, MDMA facilitated participants' reported ability to more readily fall asleep. This finding conflicts with an earlier report showing that the drug disrupts sleep (Randall et al. 2009) and our hypothesis that both drugs would negatively impact sleep. The reason for the contradictory findings with the previous study is most likely due to the fact that Randall and colleagues administered MDMA only 5 h prior to bedtime, whereas we administered the drug more than 14 h before requiring participants to go to bed. It is possible that the divergent effects of the methamphetamine and MDMA on sleep are due to their different pharmacokinetic profiles. For instance, methamphetamine has a half-life of approximately 12 h, while MDMA has a half-life of approximately 6 h (Cook et al. 1992, 1993; Mueller et al. 2009). Thus, it might be expected that methamphetamine would produce multiple stimulant effects that last considerably longer than MDMA-related effects. Indeed, heart rate remained significantly elevated 24 h following methamphetamine, but not MDMA, administration.

Based on reports suggesting that MDMA causes a temporary depressive mood state in the days following use (e.g., Parrott and Lasky 1998), we hypothesized that the drug would engender residual mood disturbances in the days immediately subsequent to its consumption. This prediction was not borne out as participants did not report negative mood states during the days following administration of either amphetamine. It is important to note, however, that anecdotally both MDMA and methamphetamine are often taken in multiple doses over the course of an evening and/or several days (e.g., Cho et al. 2001; Allott and Redman 2006). Perhaps next-day mood disruptions would have been observed if multiple drug doses were administered here.

In conclusion, this study provides additional evidence that single oral doses of methamphetamine and MDMA produced many overlapping, prototypical stimulant effects. Both drugs increased cardiovascular activity and ratings of stimulation and euphoria, while they decreased food intake. The drugs did, however, produce differences on some measures. Only methamphetamine improved cognitive performance and increased self-reported desire to take the drug again, whereas only MDMA acutely increased “negative” subjective-effect ratings. While it is possible that these differences may account for the differential public perception and abuse potential associated with these amphetamines, an alternative explanation is related to the route by which the drugs are most frequently used recreationally. MDMA is used most often via the oral route, whereas methamphetamine is used primarily via the intranasal, intravenous, and smoked routes, which are associated with greater toxicity.

Acknowledgments

The medical assistance of Drs. Benjamin R Nordstrom and David Mysels and technical assistance of Gydmer Perez and Michaela Bamdad are gratefully acknowledged. This research was supported by grant number DA-03746 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Contributor Information

Matthew G. Kirkpatrick, Department of Psychology, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA; Division on Substance Abuse, New York State Psychiatric Institute and Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University, New York, NY, USA; Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA

Erik W. Gunderson, Division on Substance Abuse, New York State Psychiatric Institute and Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University, New York, NY, USA

Audrey Y. Perez, Division on Substance Abuse, New York State Psychiatric Institute and Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University, New York, NY, USA

Margaret Haney, Division on Substance Abuse, New York State Psychiatric Institute and Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University, New York, NY, USA.

Richard W. Foltin, Division on Substance Abuse, New York State Psychiatric Institute and Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University, New York, NY, USA

Carl L. Hart, Email: clh42@columbia.edu, Department of Psychology, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA; Division on Substance Abuse, New York State Psychiatric Institute and Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University, New York, NY, USA; New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1051 Riverside Dr., Unit 120, New York, NY 10032, USA.

References

- Allott K, Redman J. Patterns of use and harm reduction practices of ecstasy users in Australia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;82:168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baicy K, London ED. Corticolimbic dysregulation and chronic methamphetamine abuse. Addiction. 2007;102(Suppl 1):5–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedi G, Hyman D, de Wit H. Is ecstasy an “empathogen”? Effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine on prosocial feelings and identification of emotional states in others. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:1134–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolla KI, McCann UD, Ricaurte GA. Memory impairment in abstinent MDMA (“ecstasy”) users. Neurology. 1998;51:1532–1537. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cami J, Farre M, Mas M, Roset PN, Poudevida S, Mas A, San L, de la Torre R. Human pharmacology of 3,4-methylenedioxyme-thamphetamine (“ecstasy”): psychomotor performance and subjective effects. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;20:455–466. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200008000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho AK, Melega WP, Kuczenski R, Segal DS. Relevance of pharmacokinetic parameters in animal models of methamphetamine abuse. Synapse. 2001;39:161–166. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(200102)39:2<161::AID-SYN7>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer SD, Haney M, Foltin RW, Fischman MW. Amphetamine self-administration by humans: modulation by contingencies associated with task performance. Psychopharmacology. 1996;127:39–46. doi: 10.1007/BF02805973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer SD, Hart CL, Ward AS, Haney M, Foltin RW, Fischman MW. Effects of repeated oral methamphetamine administration in humans. Psychopharmacology. 2001;155:397–404. doi: 10.1007/s002130100727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook CE, Jeffcoat AR, Sadler BM, Hill JM, Voyksner RD, Pugh DE, White WR, Perez-Reyes M. Pharmacokinetics of oral methamphetamine and effects of repeated daily dosing in humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 1992;20:856–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook CE, Jeffcoat AR, Hill JM, Pugh DE, Patetta PK, Sadler BM, White WR, Perez-Reyes M. Pharmacokinetics ofmethamphetamine self-administered to human subjects by smoking S-(+)-metham-phetamine hydrochloride. Drug Metab Dispos. 1993;21:717–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crean RD, Davis SA, Von Huben SN, Lay CC, Katner SN, Taffe MA. Effects of (+/−)3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, (+/−) 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine and methamphetamine on temperature and activity in rhesus macaques. Neuroscience. 2006;142:515–525. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Dudish S, Ambre J. Subjective and behavioral effects of diazepam depend on its rate of onset. Psychopharmacology. 1993;112:324–330. doi: 10.1007/BF02244928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltin RW, Fischman MW, Byrne MF. Effects of smoked marijuana on food intake and body weight of humans living in a residential laboratory. Appetite. 1988;11:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(88)80017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltin RW, Rolls BJ, Moran TH, Kelly TH, McNelis AL, Fischman MW. Caloric, but not macronutrient, compensation by humans for required-eating occasions with meals and snack varying in fat and carbohydrate. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;55:331–342. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/55.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grelotti DJ, Kanayama G, Pope HG., Jr Remission of persistent methamphetamine-induced psychosis after electroconvulsive therapy: presentation of a case and review of the literature. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:17–23. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08111695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Fischgrund BN, Parsons JT. Explanations for methamphetamine use among gay and bisexual men in New York City. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40:1331–1345. doi: 10.1081/JA-200066900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamamoto DT, Rhodus NL. Methamphetamine abuse and dentistry. Oral Dis. 2009;15:27–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2008.01459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Comer SD, Fischman MW, Foltin RW. Alprazolam increases food intake in humans. Psychopharmacology. 1997;132:311–314. doi: 10.1007/s002130050350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Ward AS, Comer SD, Hart CL, Foltin RW, Fischman MW. Bupropion SR worsens mood during marijuana withdrawal in humans. Psychopharmacology. 2001;155:171–179. doi: 10.1007/s002130000657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Gunderson EW, Rabkin J, Hart CL, Vosburg SK, Comer SD, Foltin RW. Dronabinol and marijuana in HIV-positive marijuana smokers. Caloric intake, mood and sleep. JAIDS. 2007;45:545–554. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31811ed205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CL, Ward AS, Haney M, Foltin RW, Fischman MW. Methamphetamine self-administration by humans. Psychopharmacology. 2001;157:75–81. doi: 10.1007/s002130100738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CL, Haney M, Foltin RW, Fischman MW. Effects of the NMDA antagonist memantine on human methamphetamine discrimination. Psychopharmacology. 2002;164:376–384. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1225-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CL, Ward AS, Haney M, Nasser J, Foltin RW. Methamphetamine attenuates disruptions in performance and mood during simulated night-shift work. Psychopharmacology. 2003;169:42–51. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1464-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CL, Gunderson EW, Perez A, Kirkpatrick MG, Thurmond A, Comer SD, Foltin RW. Acute physiological and behavioral effects of intranasal methamphetamine in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1847–1855. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatsukami DK, Fischman MW. Crack cocaine and cocaine hydrochloride. Are the differences myth or reality? JAMA. 1996;276:1580–1588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland J. Ecstasy: the complete guide: a comprehensive look at the risks and benefits of MDMA. Park Street Press; Rochester, VT: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi R, Mullins K, Boundy C, Brignell C, Piccini P, Curran HV. Neurocognitive function in current and ex-users of ecstasy in comparison to both matched polydrug-using controls and drug-naïve controls. Psychopharmacology. 2007;194:371–379. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0837-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johanson CE, Kilbey M, Gatchalian K, Tancer M. Discriminative stimulus effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) in humans trained to discriminate among d-amphet-amine, meta-chlorophenylpiperazine and placebo. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;81:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HE, Garrett BE, Griffiths RR. Reinforcing effects of oral cocaine: contextual determinants. Psychopharmacology. 2001;154:143–152. doi: 10.1007/s002130000626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly TH, Foltin RW, Emurian CS, Fischman MW. Performance-based testing for drugs of abuse: dose and time profiles of marijuana, amphetamine, alcohol, and diazepam. J Anal Toxicol. 1993;17:264–272. doi: 10.1093/jat/17.5.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly BC, Parsons JT, Wells BE. Prevalence and predictors of club drug use among club-going young adults in New York City. J Urban Health. 2006;83:884–895. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9057-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushida CA, Chang A, Gadkary C, Guilleminault C, Carrillo O, Dement WC. Comparison of actigraphic, polysomnographic, and subjective assessment of sleep parameters in sleep-disordered patients. Sleep Med. 2001;2:389–396. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuypers KP, Ramaekers JG. Transient memory impairment after acute dose of 75 mg 3.4-Methylene-dioxymethamphetamine. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19:633–639. doi: 10.1177/0269881105056670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liechti ME, Geyer MA, Hell D, Vollenweider FX. Effects of MDMA (ecstasy) on prepulse inhibition and habituation of startle in humans after pretreatment with citalopram, haloperidol, or ketanserin. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24:240–252. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00199-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyvers M. Recreational ecstasy use and the neurotoxic potential of MDMA: current status of the controversy and methodological issues. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2006;25:269–276. doi: 10.1080/09595230600657758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrone GF, Pardo JS, Krauss RM, Hart CL. Amphetamine analogs methamphetamine and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) differentially affect speech. Psychopharmacology. 2010;208:169–177. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1715-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod DR, Griffiths RR, Bigelow GE, Yingling J. An automated version of the digit symbol substitution test (DSST) Behav Res Meth Instrum. 1982;14:463–436. [Google Scholar]

- Miller TP, Taylor JL, Tinklenberg JR. A comparison of assessment techniques measuring the effects of methylphenidate, secobarbital, diazepam and diphenhydramine in abstinent alcoholics. Neuropsychobiology. 1988;19:90–96. doi: 10.1159/000118441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohs RC, Tinklenberg JR, Roth WT, Kopell BS. Methamphetamine and diphenhydramine effects on the rate of cognitive processing. Psychopharmacology. 1978;59:13–19. doi: 10.1007/BF00428024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller M, Kolbrich EA, Peters FT, Maurer HH, McCann UD, Huestis MA, Ricaurte GA. Direct comparison of (+/−) 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (“ecstasy”) disposition and metabolism in squirrel monkeys and humans. Ther Drug Monit. 2009;31:367–373. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e3181a4f6c2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott AC, Lasky J. Ecstasy (MDMA) effects upon mood and cognition: before, during and after a Saturday night dance. Psychopharmacology. 1998;139:261–268. doi: 10.1007/s002130050714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez GA, Haney M, Foltin RW, Hart CL. Modafinil decreases food intake in humans subjected to simulated shift work. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008a;90:717–722. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez AY, Kirkpatrick MG, Gunderson EW, Marrone G, Silver R, Foltin RW, Hart CL. Residual effects of intranasal methamphetamine on sleep, mood, and performance. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008b;94:258–262. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peroutka SJ, Newman H, Harris H. Subjective effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine in recreational users. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1988;1:273–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall S, Johanson CE, Tancer M, Roehrs T. Effects of acute 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine on sleep and daytime sleepiness in MDMA users: a preliminary study. Sleep. 2009;32:1513–1519. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.11.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers J, Buchanan T, Pearson C, Parrott AC, Ling J, Hefferman TM, Scholey AB. Differential experiences of the psychobiological sequelae of ecstasy use: quantitative and qualitative data from an internet study. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20:437–446. doi: 10.1177/0269881105058777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman RB, Baumann MH, Dersch CM, Romero DV, Rice KC, Carroll FI, Partilla JS. Amphetamine-type central nervous system stimulants release norepinephrine more potently than they release dopamine and serotonin. Synapse. 2001;39:32–41. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(20010101)39:1<32::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silber BY, Croft RJ, Papafotiou K, Stough C. The acute effects of d-amphetamine and methamphetamine on attention and psychomotor performance. Psychopharmacology. 2006;187:154–169. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0410-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, Kirby KC, Griffiths RR. Modulation of drug reinforcement by behavioral requirements following drug ingestion. Psychopharmacology. 1994a;114:243–247. doi: 10.1007/BF02244844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, Mumford GK, Griffiths RR. Enhancing caffeine reinforcement by behavioral requirements following drug ingestion. Psychopharmacology. 1994b;114:424–432. doi: 10.1007/BF02249332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon SL, Richardson K, Dacey J, Glynn S, Domier CP, Rawson RA, Ling W. A comparison of patterns of methamphetamine and cocaine use. J Addict Dis. 2002;21:35–44. doi: 10.1300/j069v21n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoops WW, Lile JA, Fillmore MT, Glaser PE, Rush CR. Reinforcing effects of methylphenidate: influence of dose and behavioral demands following drug administration. Psychopharmacology. 2005a;177:349–355. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1946-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoops WW, Lile JA, Fillmore MT, Glaser PE, Rush CR. Reinforcing effects of modafinil: influence of dose and behavioral demands following drug administration. Psychopharmacology. 2005b;182:186–193. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tancer ME, Johanson CE. The subjective effects of MDMA and mCPP inmoderate MDMA users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;65:97–101. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tancer M, Johanson CE. Reinforcing, subjective, and physiological effects of MDMA in humans: a comparison with d-amphetamine and mCPP. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;72:33–44. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollenweider FX, Gamma A, Liechti M, Huber T. Psychological and cardiovascular effects and short-term sequelae of MDMA (“ecstasy”) in MDMA-naive healthy volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998;19:241–251. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00013-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Woolverton WL. Estimating the relative reinforcing strength of (+/−)-3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) and its isomers in rhesus monkeys: comparison to (+)-methamphetamine. Psychopharmacology. 2007;189:483–488. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0599-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesnes K, Warburton DM. Effects of smoking on rapid information processing performance. Neuropsychobiology. 1983;9:223–229. doi: 10.1159/000117969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]