Abstract

“Medical pluralism” is the use of multiple health systems and is common among people living with HIV/AIDS in sub Saharan Africa. Healers and traditional birth attendants (TBAs) often are a patient's first and/or preferred line of treatment; this often results in delayed, interrupted, or abandoned diagnosis and therapy. Literature from the study of medical pluralism suggests that HIV care and treatment programs are infrequently and inconsistently engaging healers around the world. Mistrust and misunderstanding among patients, clinical providers, and traditional practitioners make the development of effective partnerships difficult, particularly regarding early HIV diagnosis and antiretroviral therapy. We provide recommendations for the development of successful collaboration health workforce efforts based on both published articles and case studies from our work in rural Mozambique.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, traditional healer, traditional birth attendant, community engagement, community-clinic linkage, community health worker, testing referral, Antenatal care (ANC), Elimination of mother-to-child transmission (EMTCT), Sub-Saharan Africa, Mozambique

Introduction

Medical pluralism (the use of multiple health systems) is common among people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHIV) in sub Saharan Africa (SSA) [1-4]. Throughout SSA, healers and traditional birth attendants (TBAs) can act as a patient's first (and often preferred) line of treatment [5-21]. Healers specialize in different forms of treatment, e.g., herbal, spiritual, religious[12, 14, 21-25] and address ailments from spiritual sources, e.g., spirits, sorcery, and social transgressions. TBAs and healers are more readily available to patients, particularly in rural areas, and are perceived as an alternative to inadequate allopathic services [26]. Healers and TBAs do not necessary believe themselves to be competing with allopathic clinics: healers believe they treat the spiritual component of the disease while the clinician treats the biological agent [27].

Seeking care from a traditional healer before an allopathic provider can result in delayed or interrupted HIV treatment engagement, leading to poorer health outcomes and higher rates of transmission. Within ART-based HIV programs, healers have demonstrably hindered the prompt provision of HIV services in some studies [2, 28] while showing little impact in others [29]. For PLHIV, the long-term effects of delayed, interrupted, or discontinued ART are severe, both due to rapid disease progression and the risk of transmission to sexual partners [30-34]. People with a CD4+ cell count <200/μL are especially infectious with rising viral loads as the immune system deteriorates, and are themselves at enormous risk of opportunistic infections and malignancies that are preventable with earlier ART [35, 36]. In addition to personal risk, pregnant HIV-infected women who delay or abandon care increase the risk of maternal transmission [37-39].

Patient retention in care and optimal adherence to medications has been an ongoing struggle in SSA. With retention rates below 60% in some regions [40-42], factors for loss to follow up include: male gender, WHO clinical stage IV, low BMI, heavy alcohol consumption, stigma, health service delivery issues, and a preference for alternative health practitioners [43]. The occurrence of healers “poaching” unsatisfied HIV-infected patients, health consequences of patients bouncing back and forth between the two systems, and impact of herbal remedies on viral suppression is underexplored [44]. These data are difficult to capture for several reasons: (1) it can be difficult to locate patients who have abandoned care; (2) patients may be unwilling (or unable) to disclose the exact herb name and dosage of alternative treatments they are receiving [45, 46]; and (3) healers are often suspicious of revealing the treatments they provide, fearing the allopathic system will steal it without compensation [3, 47].

Challenges in the HIV Care Continuum: The impact of traditional practitioners

The HIV care continuum – also called the HIV treatment cascade—is a model for HIV treatment programs used to identify barriers to successful viral suppression of all HIV infected patients [48]. This cascade includes: (1) HIV diagnosis; (2) linkage to HIV care; (3) retention in HIV care; (4) enrollment on ART (if eligible); and (5) viral load suppression. Understanding the impact of traditional practitioner behavior on each point in the cascade can inform future interventions to improve patient outcomes.

Patients who receive treatment from a traditional healer may be delayed in engaging allopathic services [28]. A diagnosis from a healer or TBA will typically result in weeks or even months of treatment; failure to resolve the problem can lead a patient to visit a different healer (thus further delaying testing or treatment) or lead to allopathic health seeking. Alternatively, healers can facilitate an early diagnosis by referring suspected HIV-infected patients to testing centers [27]. Healers, if properly trained and motivated, can act as a screening system for serious infectious and chronic illnesses among their patients [3, 27, 49-51]. In addition to their timely referral, healers could be a resource for clinicians and provide pertinent details about patients’ medical history that may point to a diagnosis. This can be particularly important for people who are too embarrassed or think it inappropriate to disclose certain symptoms (including STIs, HIV and depression), sexual behavior, and/or adherence to medications [52, 53].

While researchers often highlight the negative impact of TBAs and healers, they also serve a positive role as patient health advocates, mental health practitioners, and primary care providers. Examples include training traditional healers as referral agents or adherence coaches for HIV and tuberculosis in South Africa, The Gambia, Tanzania, and Lesotho [50, 54, 55]. South African healers who received training in HIV/AIDS, STI, and TB prevention were found to have a significant increase in HIV/AIDS knowledge and HIV management strategies [50]. In an evaluation of the modern allopathic medical training model for healers in rural Nepal, trained healers maintained knowledge about the causes, prevention, and treatment of HIV/AIDS, increased referrals to health posts, and improved relationships with government health workers. In contrast, untrained healers continued to solely utilize traditional treatments without referral to allopathic providers [56]. Several studies have demonstrated that traditional healer interventions result in the assimilation of new skills and knowledge, but few studies have linked these interventions to improved health outcomes for HIV-infected patients. Given the value of initiating ART in resource poor settings, patient referral to ART clinics by traditional healers is a critical method of improving the burden of HIV in a community. One example where healers and clinicians successfully collaborated to improve this linkage to treatment was conducted in rural Lesotho, where healers both referred patients to HIV treatment facilities and actively monitored patients on ART [57].

Despite interest in assisting PLHIV, healers often lack ART/HIV knowledge and awareness of herb-ART interactions [8, 44-47]. Fundamental differences in disease causation beliefs can make it difficult for clinicians and traditional practitioners to communicate effectively and agree on a course of action. Additionally, collaborations between allopathic medicine and traditional medicine can be unilateral and paternalistic, and healers and TBAs have reported feeling a lack of respect for their contributions [57]. Future interventions need to take these barriers into account.

Case Study: Rural North-Central Mozambique

Vanderbilt University (VU), through its non-governmental organization (NGO) affiliate, Friends in Global Health (FGH), supports 82 rural HIV service sites in Zambézia province with PEPFAR funding from the CDC. Among the world's poorest and most medically underserved regions, Zambézia had an adult HIV prevalence of 12.6% in 2009 [58]. FGH-supported clinical sites are providing ART to ~18,000 persons, including 10,000 pregnant women and their infants each year. High rates of loss-to-follow up and high risk of mortality among HIV-infected adults and infants remains our greatest barriers to success [59, 60]. Patients report concerns with disclosure/stigma [61], gender based violence [62], lack of food and/or transportation [61], perceptions of poor health care [26], and a preference for traditional medicine [24, 62] in their decision to abandon care. Pregnant women report similar reasons for refusing testing and/or treatment, with the addition of disagreement with clinical practices [63], a lack of service availability [64], increased social status if they deliver at home [65], fear of witchcraft (if the pregnancy is disclosed too early) [66-69], a lack of social and financial support from family members [70], and differing concepts on symptom causation and appropriate treatments [63, 68].

While HIV care and treatment is being scaled up across the province, far too few health care workers practice in rural SSA [71-73]. In Zambézia province, only an estimated 50 physicians and 850 nurses cared for a population of 4.4 million in 2014. Over 25,000 traditional healers are registered with the Mozambican Ministry of Health (MISAU) and an estimated 1,500 TBAs are practicing in the province (as of early 2015). Clinicians have blamed healers and TBAs for delaying patient testing and enrollment in allopathic care leading to mutual mistrust and lack of respect [61]. Given the overwhelming underrepresentation of physicians and nurses, health care workers are beginning to see the importance of working alongside healers and TBAs rather than treating them as a barrier. Below are two examples of successful integration of traditional practitioners from our work in Mozambique.

1. Current Engagement with Traditional Healers

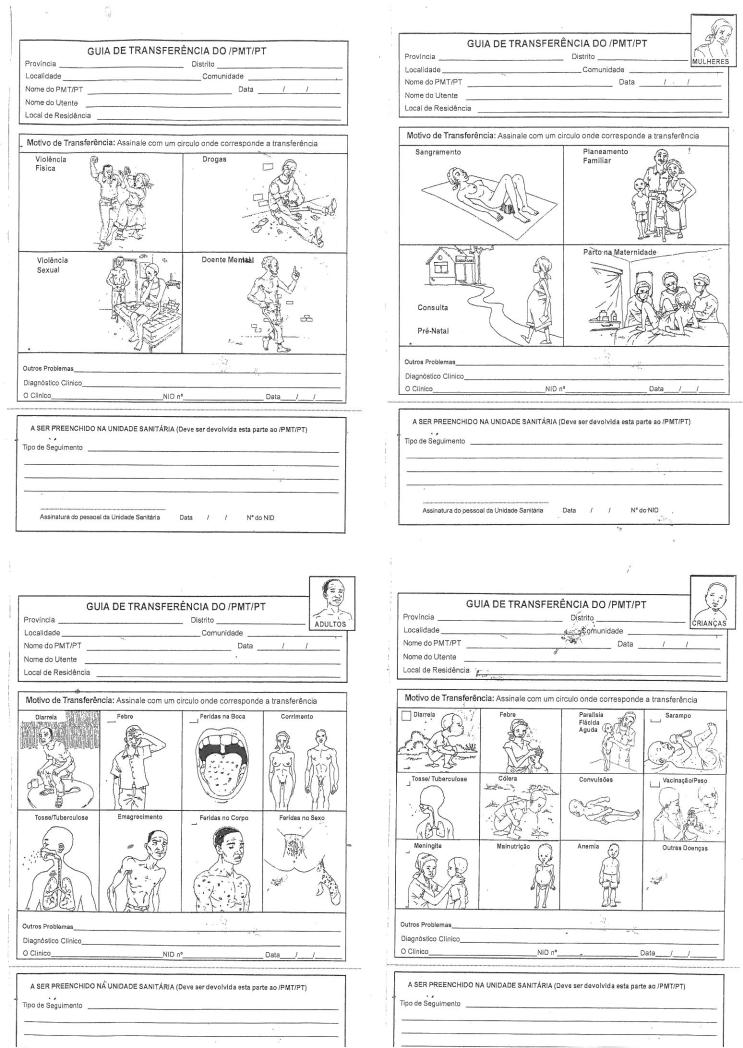

The clear association between delays in HIV testing and use of a traditional healer in Mozambique was used to support accusations that healers do not refer patients who need allopathic services in a timely manner. Healers responded to this complaint with the argument that while they refer patients, the health system does not appropriately test and treat referred patients, and often patients end up returning to their care. To document healer referrals, clinicians, healers, and two artists collaborated to create pictorial referral forms representing common adult, pediatric, and maternal conditions that would necessitate transfer to the health facility (Figure 1) [27]. These forms, designed in association with healers throughout the province, allowed healers to document their referral practices; the diagnosis section of the form allowed us to determine the treatment prescribed by clinicians. Educational sessions to improve symptom identification resulted in 35% referral rates and increased healer knowledge about HIV, TB, and malaria symptoms, transmission and treatment [27]. While healers referred more patients, clinicians were less inclined to take them seriously: healer symptoms frequently indicated the need to test patients for TB or HIV, but less than 4% who sought allopathic care were tested, highlighting the importance of total buy-in among all health providers [27].

Figure 1.

Healer referral forms

2. Current Engagement with TBAs

Despite high levels of ANC service uptake in all other provinces (>90%) within Mozambique, the DHS estimates that only 74% of women in Zambézia province attended at least one ANC visit and only 38% attended all four appointments [74]. While uptake of ANC services is low, almost 100% of women will seek services from a TBA during pregnancy. Focus groups and individual interviews in this district revealed a community interest in engaging TBAs in the formal health system in some capacity. These same groups highlighted the importance of community and family support for women's uptake of ANC services. TBAs believed they were in a position to increase uptake of ANC services, including HIV testing, treatment initiation, and early infant diagnosis, if they were both properly trained. All active and interested TBAs who provided “prenatal” care to women in catchment areas were provided bi-annual instruction about recommended and available ANC/elimination of mother-to-child transmission (EMTCT) services through a three day basic course taught by Ministry of Health clinicians and counselors.

In conjunction with increased male partner engagement and clinical changes to promote couples-based testing and treatment, TBAs acted as a “first-line counselor” about the importance of ANC service uptake and as a companion during ANC and child wellness visits. Over two years, 68 TBAs counselled 3,528 pregnant women about the importance of attending ANC services and accompanied 1,753 to their first ANC visit. During the course of the intervention, uptake of maternal testing for HIV during ANC increased (81% vs 92%; p=<0.001) as did uptake of comprehensive ART (11% vs 35%; p=<0.001) [75]. The clinical implications for pregnant women were impressive, but TBAs also benefited from increased social status in the community and a decline in accusations of TBA witchcraft. We have anecdotal indications that there have also be declines in the associated violence that witchcraft accusations carry.

Recommendations for Healer and TBA engagement in HIV programs

Before healers or TBAs can be linked formally with any health system, all key stakeholders must be willing to openly communicate and address social, cultural, and logistical barriers to engagement. Agreement about the need for changes in healer and TBA roles in patient health care, systems for documenting activities, and improved training programs are essential to successful engagement.

1. Structural Changes in Clinical Settings

Two structural changes in clinical settings are necessary to ensure successful engagement of traditional practitioners. (1) Identifying and agreeing upon formal positions/roles for traditional healers and TBAs can be difficult, but is essential to program success. We recommend a variety of positions, depending on training and ability, as limiting all healers to a single role, regardless of ability, defies common sense; and (2) Engaging traditional healers and TBAs into the allopathic health system will require the creation or modification of referral/treatment records. Given low literacy and numeracy rates among community practitioners, it is unreasonable to expect traditional healers or TBAs to fill out standard clinical forms. The creation of locally produced pictorial forms to track patient symptoms and treatment is essential to tracking success and providing feedback to patients and providers.

2. Training Needs for Healers

In addition to a basic understanding of the local health system and the clinicians practicing in their region, healers who partner with health systems should have the knowledge and skills to effectively: (1) Identify signs and symptoms of HIV infection; (2) Educate PLHIV about ART, EMTCT, and HIV care (including infant care); (3) Assess serious ART side effects or HIV co-infections; (4) Counsel patients about safer strategies for partner disclosure (with assistance if needed); (5) Advocate for quality health care delivery when assisting each patient; and (6) Resolve conflict between patients/health care providers/themselves.

Two additional components are also essential: (7) Education about the potential implications of herb-ART interactions. By engaging healers, there is concern that healer engagement is harmful through co-administration of potentially hepato- and/or nephrotoxic agents with deleterious drug-ART interactions [3, 4, 8, 44-47, 51]. For example, Hypoxoside, specifically H. hemerocallidea and H. colchicifolia are popular herbal remedies in SSA used as immunostimulants for PLHIV [47]. In in vitro models Hypoxis was found to possess the potential to interact with HIV drug metabolizing enzymes, with risks of subsequent drug resistance, toxicity, and/or treatment failure [47]. Healers need to be exceedingly cautious to not prescribe specific medications while patients are concurrently taking ART or other allopathic medications; (8) Emphasize the importance of blood safety. Similar to other southern African countries, healers in Mozambique practice a traditional vaccination treatment where a razor blade is used to make sub-cutaneous cuts in order to rub herbs into the bloodstream. Believed to be a stronger treatment than ingestion of herbs, this type of treatment places both the healer and patient at risk of blood borne pathogens. The theoretical risk of HIV and hepatitis C transmission is high among healers and their patients considering the infrequency of razor sanitization and glove use.

3. Clinician Attitude Changes

Successful interventions rely on collaboration through the cultivation of trust between the traditional healers and the research team [76]. Strategies to change clinician attitudes and behavior towards traditional practitioners and their patients’ are essential and often overlooked when creating an integrated community-clinical system. Effective mechanisms for improving attitudes in this context have not been sufficiently designed, tested, or validated [50].

4. Patient Buy-in

Patient buy-in needs to be determined early in the engagement process. If patients are uninterested or unsupportive of healer/TBA/clinician partnerships, even a well-designed system will fail.

5. Recruitment of Effective Traditional Partners

Not all healers can be effective partners within the health system, nor will funds always be available to train/incentivize all traditional practitioners. A screening system, beyond self-reported interest, that can identify appropriate partners for patient engagement has yet to be designed and validated [27, 50, 57, 77].

Future Directions: Healers as adherence counselors

Community-based treatment partners can improve pharmacy adherence and loss-to-follow up (LTFU), while decreasing stigma and isolation [78-82]. Managing HIV care and treatment in secret is exceedingly difficult, yet many people living with HIV fear for HIV stigma more than the possibility of poor health outcomes [83]. To combat this, many health systems require that patients initiating ART provide the name and contact information of a “treatment partner” who is aware of their HIV status and medication requirements. This is intended to ensure community-based support and provide a contact in case the patient is lost-to-follow up. This policy can be problematic, however, for patients who fear HIV-related stigma and discrimination by people in their circle of trust (partner, friend) or when family and friends do not have the skills/knowledge to adequately support treatment. Traditional healers and TBAs can act as treatment partners and assist patients with partner disclosure, initiate community/clinical systems of assistance if gender based violence is threatened/occurs, and advocate for patients during clinical visits to ensure quality care is provided.

Conclusions

A fundamental shift in the role of traditional practitioners in HIV care and treatment programs will be necessary to reduce treatment delays, interruptions, and abandonment, as well as guard against potential herb-drug interactions in areas where healer/TBA use is high. Partnership between traditional practitioners and the health system requires a significant commitment of time and finances at the beginning, and is not reached without controversy and challenges. Despite these challenges, we cannot afford to ignore the potential value of partnering with the thousands of traditional healers and TBAs already providing health services to underserved communities.

Acknowledgment

Sources of Funding: Funding for CMA was provided by CTSA award No. KL2TR000446.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Carolyn M. Audet, Erin Hamilton, Leighann Hughart, and Jose Salato declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

REFERENCES

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Moshabela M, et al. Patterns and implications of medical pluralism among HIV/AIDS patients in rural South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(4):842–52. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9747-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okome-Nkoumou M, et al. Delay between first HIV-related symptoms and diagnosis of HIV infection in patients attending the internal medicine department of the Fondation Jeanne Ebori (FJE), Libreville, Gabon. HIV Clin Trials. 2005;6(1):38–42. doi: 10.1310/ULR3-VN8N-KKB5-05UV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peltzer K, et al. Traditional complementary and alternative medicine and antiretroviral treatment adherence among HIV patients in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2010;7(2):125–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peltzer K, et al. Antiretrovirals and the use of traditional, complementary and alternative medicine by HIV patients in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa: a longitudinal study. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2011;8(4):337–45. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v8i4.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodeker G, Willcox M. New research initiative on plant-based antimalarials. Lancet. 2000;355(9205):761. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)72181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Homsy J, et al. Traditional health practitioners are key to scaling up comprehensive care for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2004;18(12):1723–5. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000131380.30479.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Homsy J, et al. Defining minimum standards of practice for incorporating African traditional medicine into HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and support: a regional initiative in eastern and southern Africa. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10(5):905–10. doi: 10.1089/acm.2004.10.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babb DA, et al. Use of traditional medicine by HIV-infected individuals in South Africa in the era of antiretroviral therapy. Psychol Health Med. 2007;12(3):314–20. doi: 10.1080/13548500600621511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bodeker G. Complementary medicine and evidence. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2000;29(1):3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burford G, et al. Traditional medicine and HIV/AIDS in Africa: a report from the International Conference on Medicinal Plants, Traditional Medicine and Local Communities in Africa (a parallel session to the Fifth Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity, Nairobi, Kenya, May 16-19, 2000). J Altern Complement Med. 2000;6(5):457–71. doi: 10.1089/acm.2000.6.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleming J. Mozambican healers join government in fight against AIDS. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care. 1995;1(2):32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green EC. Traditional healers and AIDS in Uganda. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medince. 1999;6(1):1–2. doi: 10.1089/acm.2000.6.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green EC. The participation of Africa Traditional Healers in AIDS/STI prevention programmes. AIDSLink. 1995;(26):14–15. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green EC, Zokwe B, Dupree JD. The experience of an AIDS prevention program focused on South African traditional healers. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(4):503–15. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)e0105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green EC. AIDS and STDs in Africa: bridging the gap between traditional healing and modern medicine. Westview Press; Boulder: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 16.King R. Collaboration with traditional healers in HIV/AIDS prevention and care in sub-Saharan Africa: a literature review. UNAIDS Best Practices Collection. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liverpool J, et al. Western medicine and traditional healers: partners in the fight against HIV/AIDS. J Natl Med Assoc. 2004;96(6):822–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mills E, et al. The challenges of involving traditional healers in HIV/AIDS care. Int J STD AIDS. 2006;17(6):360–3. doi: 10.1258/095646206777323382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris K. South Africa tests traditional medicines. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2(6):319. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00302-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munk K. Traditional healers, traditional hospitals and HIV / AIDS: a case study in KwaZulu-Natal. AIDS Anal Afr. 1997;7(6):10–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kale R. Traditional healers in South Africa: a parallel health care system. BMJ. 1995;310(6988):1182–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6988.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfeiffer J. Commodity fetichismo, the Holy Spirit, and the turn to Pentecostal and African Independent Churches in Central Mozambique. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2005;29(3):255–83. doi: 10.1007/s11013-005-9168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Audet CM, et al. Sociocultural and epidemiological aspects of HIV/AIDS in Mozambique. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2010;10:15. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-10-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Audet CM, et al. Health Seeking Behavior in Zambezia Province, Mozambique. SAHARAJ. 2012;9(1):41–46. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2012.665257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Audet CM, et al. HIV/AIDS-Related Attitudes and Practices Among Traditional Healers in Zambezia Province, Mozambique. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medince. 2012;18(12):1–9. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Audet CM, et al. Poor quality health services and lack of program support leads to low uptake of HIV testing in rural Mozambique. Journal of African AIDS Research. 2012;4:327–335. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2012.754832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27••.Audet CM, et al. Educational Intervention Increased Referrals to Allopathic Care by Traditional Healers in Three High HIV-Prevalence Rural Districts in Mozambique. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e70326. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070326. [This article provides an example of implementing an educational intervention to increase healer patient referrals in rural SSA. Highlights two difficulties in the development of an effective traditional practitioner partnership, including: (1) identifying which healers to partner with; and (2) how to engage clinicians effectively.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28••.Audet CM, et al. Symptomatic HIV-positive persons in rural Mozambique who first consult a traditional healer have delays in HIV testing: A cross-sectional study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000194. [This article presents the results of a cross-sectional study detailing the health seeking behavior of undiagnosed symptomatic HIV-infected patients in rural Mozambique. This study reveals that people who first visited a traditional healer had significant delays to testing.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29••.Horwitz RH, et al. No Association Found Between Traditional Healer Use and Delayed Antiretroviral Initiation in Rural Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0132-7. [This article presents the results of a cross-sectional study detailing the health seeking behavior of newly diagnosed HIV-infected patients in rural Uganda. This study reveals no impact of healer use on patient outcomes.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vermund SH, Allen KL, Karim QA. HIV-prevention science at a crossroads: advances in reducing sexual risk. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2009;4(4):266–73. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32832c91dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Modjarrad K, Chamot E, Vermund SH. Impact of small reductions in plasma HIV RNA levels on the risk of heterosexual transmission and disease progression. AIDS. 2008;22(16):2179–85. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328312c756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Attia S, et al. Sexual transmission of HIV according to viral load and antiretroviral therapy: systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009;23(11):1397–404. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832b7dca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quinn TC, et al. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Rakai Project Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(13):921–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quinn TC. Viral load, circumcision and heterosexual transmission. Hopkins HIV Rep. 2000;125(3):1, 11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naba MR, et al. Profile of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected patients at a tertiary care center in Lebanon. J Infect Public Health. 2010;3(3):130–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson MA, et al. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2010 recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA panel. JAMA. 2010;304(3):321–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fowler MG, et al. Efficacy and safety of an extended nevirapine regimen in infants of breastfeeding mothers with HIV-1 infection for prevention of HIV-1 transmission (HPTN 046): 18-month results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65(3):366–74. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lallemant M, et al. A trial of shortened zidovudine regimens to prevent mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Perinatal HIV Prevention Trial (Thailand) Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(14):982–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010053431401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guay LA, et al. Intrapartum and neonatal single-dose nevirapine compared with zidovudine for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Kampala, Uganda: HIVNET 012 randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;354(9181):795–802. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)80008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalembo FW, Zgambo M. Loss to Followup: A Major Challenge to Successful Implementation of Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV-1 Programs in Sub-Saharan Africa. ISRN AIDS. 20122012:589817. doi: 10.5402/2012/589817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bastard M, et al. Adults receiving HIV care before the start of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: patient outcomes and associated risk factors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64(5):455–63. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a61e8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosen S, Fox MP, Gill CJ. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):e298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.World Health Organization . In: Retention in HIV Programmes: Defining the challenges and identifying solutions. H.A. Programme, editor. Geneva: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cordier W, Steenkamp V. Drug interactions in African herbal remedies. Drug Metabol Drug Interact. 2011;26(2):53–63. doi: 10.1515/DMDI.2011.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Langlois-Klassen D, et al. Use of traditional herbal medicine by AIDS patients in Kabarole District, western Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77(4):757–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Langlois-Klassen D, Kipp W, Rubaale T. Who's talking? Communication between health providers and HIV-infected adults related to herbal medicine for AIDS treatment in western Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(1):165–76. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mills E, et al. African herbal medicines in the treatment of HIV: Hypoxis and Sutherlandia. An overview of evidence and pharmacology. Nutr J. 2005;4:19. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-4-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hull MW, Wu Z, Montaner JS. Optimizing the engagement of care cascade: a critical step to maximize the impact of HIV treatment as prevention. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012;7(6):579–86. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e3283590617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peltzer K, Mngqundaniso N. Patients consulting traditional health practioners in the context of HIV/AIDS in urban areas in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2008;5(4):370–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peltzer K, Mngqundaniso N, Petros G. A controlled study of an HIV/AIDS/STI/TB intervention with traditional healers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(6):683–90. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9110-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peltzer K, Phaswana-Mafuya N, Treger L. Use of traditional and complementary health practices in prenatal, delivery and postnatal care in the context of HIV transmission from mother to child (PMTCT) in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2009;6(2):155–62. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v6i2.57087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sankar P, Jones NL. To tell or not to tell: primary care patients' disclosure deliberations. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(20):2378–83. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.20.2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arkell J, et al. Factors associated with anxiety in patients attending a sexually transmitted infection clinic: qualitative survey. Int J STD AIDS. 2006;17(5):299–303. doi: 10.1258/095646206776790097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harper ME, et al. Traditional healers participate in tuberculosis control in The Gambia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8(10):1266–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kayombo EJ, et al. Experience of initiating collaboration of traditional healers in managing HIV and AIDS in Tanzania. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2007;3:6. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Poudel KC, et al. Retention and effectiveness of HIV/AIDS training of traditional healers in far western Nepal. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10(7):640–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Furin J. The role of traditional healers in community-based HIV care in rural Lesotho. J Community Health. 2011;36(5):849–56. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9385-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ministério da Saúde and Instituto Nacional de Saude Inquérito Nacional de Prevalência, Riscos Comportamentais e Informação sobre o HIV e SIDA em Moçambique: Relatório Preliminar sobre a Prevalência da Infecção por HIV. INSIDA. 2009 Available from: http://xa.yimg.com/kq/groups/15255898/801713730/name/INSIDA.

- 59.Vermund SH, et al. Poor clinical outcomes for HIV infected children on antiretroviral therapy in rural Mozambique: need for program quality improvement and community engagement. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e110116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blevins M, et al. Two-Year Death and Loss to Follow-Up Outcomes by Source of Referral to HIV Care for HIV-Infected Patients Initiating Antiretroviral Therapy in Rural Mozambique. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014 doi: 10.1089/aid.2014.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Groh K, et al. Barriers to antiretroviral therapy adherence in rural Mozambique. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:650. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.da Silva M, et al. Patient Loss to Follow-Up Before Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation in Rural Mozambique. AIDS and Behavior. 2014:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0874-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kyomuhendo GB. Low use of rural maternity services in Uganda: impact of women's status, traditional beliefs and limited resources. Reprod Health Matters. 2003;11(21):16–26. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(03)02176-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kowalewski M, Jahn A, Kimatta SS. Why do at-risk mothers fail to reach referral level? Barriers beyond distance and cost. Afr J Reprod Health. 2000;4(1):100–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bazzano AN, et al. Social costs of skilled attendance at birth in rural Ghana. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;102(1):91–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jansen I. Decision making in childbirth: the influence of traditional structures in a Ghanaian village. Int Nurs Rev. 2006;53(1):41–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2006.00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ogujuyigbe PA, Liasu A. Perception and health-seeking behaviour of Nigerian women about pregnancy-related risks: strategies for improvement. J Chin Clin Med. 2007;2(11):643–654. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chapman RR. Endangering safe motherhood in Mozambique: prenatal care as pregnancy risk. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(2):355–74. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00363-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maimbolwa MC, et al. Cultural childbirth practices and beliefs in Zambia. J Adv Nurs. 2003;43(3):263–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mrisho M, et al. The use of antenatal and postnatal care: perspectives and experiences of women and health care providers in rural southern Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Torpey KE, et al. Adherence support workers: a way to address human resource constraints in antiretroviral treatment programs in the public health setting in Zambia. PLoS One. 2008;3(5):e2204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zachariah R, et al. Task shifting in HIV/AIDS: opportunities, challenges and proposed actions for sub-Saharan Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103(6):549–58. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Callaghan M, Ford N, Schneider H. A systematic review of task- shifting for HIV treatment and care in Africa. Hum Resour Health. 2010:8. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ministerio da Saude (MISAU), Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE), and ICF International (ICFI) Moçambique Inquérito Demográfico e de Saúde. MISAU, INE e ICFI; Calverton, Maryland, USA: 2011. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Audet C, et al. AIDS. Melbourne, Australia: 2014. Promoting Male Involvement in Antenatal Care in Rural North Central Mozambique. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kayombo E, et al. Experience of initiating collaboration of traditional healers in managing HIV and AIDS in Tanzania. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2007;3(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ssali A, et al. Traditional Healers for HIV/AIDS Prevention and Family Planning, Kiboga District, Uganda: Evaluation of a Program to Improve Practices. AIDS and Behavior. 2005;9(4):485–493. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78•.O'Laughlin KN, et al. How treatment partners help: social analysis of an African adherence support intervention. Describes the impact of social isolation that can result from an HIV diagnosis. AIDS Behav. The authors propose the use of treatment partners to improve the physical and social well-being of people living with HIV. 2012;16(5):1308–15. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0038-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Farmer P, et al. Community-based treatment of advanced HIV disease: introducing DOT-HAART (directly observed therapy with highly active antiretroviral therapy). Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79(12):1145–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rich ML, et al. Excellent clinical outcomes and high retention in care among adults in a community-based HIV treatment program in rural Rwanda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(3):e35–42. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824476c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Koenig SP, Leandre F, Farmer PE. Scaling-up HIV treatment programmes in resource-limited settings: the rural Haiti experience. AIDS. 2004;18(Suppl 3):S21–5. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200406003-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Farmer P, et al. Community-based approaches to HIV treatment in resource-poor settings. Lancet. 2001;358(9279):404–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05550-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Johnson M, et al. Primary Relationships, HIV Treatment Adherence, and Virologic Control. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16(6):1511–1521. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0021-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Campbell-Hall V, et al. Collaboration between traditional practitioners and primary health care staff in South Africa: developing a workable partnership for community mental health services. Transcult Psychiatry. 2010;47(4):610–28. doi: 10.1177/1363461510383459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]