Abstract

Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) has been identified as one of the most important fibrogenic cytokines associated with Peyronie's disease (PD). The mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 7 (SMAD7) is an inhibitory Smad protein that blocks TGF-β signaling pathway. The aim of this study was to examine the anti-fibrotic effect of the SMAD7 gene in primary fibroblasts derived from human PD plaques. PD fibroblasts were pretreated with the SMAD7 gene and then stimulated with TGF-β1. Treated fibroblasts were used for Western blotting, fluorescent immunocytochemistry, hydroxyproline determination, and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick-end labeling assays. Overexpression of the SMAD7 gene inhibited TGF-β1-induced phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of SMAD2 and SMAD3, transdifferentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, and quashed TGF-β1-induced production of extracellular matrix protein and hydroxyproline. Overexpression of the SMAD7 gene decreased the expression of cyclin D1 (a positive cell cycle regulator) and induced the expression of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1, which is known to terminate Smad-mediated transcription, in PD fibroblasts. These findings suggest that the blocking of the TGF-β pathway by use of SMAD7 may be a promising therapeutic strategy for the treatment of PD.

Keywords: cell culture, decapentaplegic homolog 7, fibrosis, Peyronie's disease, transforming growth factor-beta

INTRODUCTION

Peyronie's disease (PD) is a relatively common condition affecting up to 9% of the male population.1,2 The etiology of PD is not fully understood. Recent studies suggest that repeated trauma to the penis during sexual intercourse may induce localized inflammatory process and aberrant wound healing in tunica albuginea, which is responsible for the plaque development and subsequent penile curvature.3,4 Despite intensive research into the pathogenesis of PD, the effective nonsurgical or medical treatment options for this entity are relatively lacking.5,6 Randomized controlled trials revealed that intralesional injection of collagenase Clostridium histolyticum and interferon-alpha, or oral administration of pentoxifylline and acetyl-L-carnitine induced improvement in penile curvature in PD patients.7,8,9,10,11 Although an uncontrolled study of verapamil injection demonstrated efficacy in reducing penile curvature,12 a recent randomized placebo-controlled trial failed to show improvement in penile curvature.13

Accumulating evidence suggests that the overexpression of profibrotic cytokines is involved in the pathogenesis of PD.14 Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) is one of the most studied cytokines associated with PD. The expression and activity of TGF-β1 protein as well as their down-stream intracellular signaling mediators involved in tissue fibrosis, such as mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 2 (SMAD2) and SMAD3, were shown to have increased in human PD plaque tissue or fibroblasts derived from human PD plaques.15,16,17 These findings give us the rationale to use TGF-β blockade for the treatment of PD. We previously observed that inhibition of the TGF-β pathway using small-molecule inhibitor of activin receptor-like kinase 5, a TGF-β type I receptor, accelerated regression of fibrotic plaques in a rat model of PD in vivo18 and suppressed production of extracellular matrix proteins in primary cultured fibroblasts isolated from human PD plaque in vitro.17 Moreover, we observed in human PD fibroblasts that small interfering RNA-mediated silencing of histone deacetylase 2 quashed TGF-β1-induced profibrotic responses by blocking activation of SMAD2 and SMAD3.19 It was also reported in human PD fibroblasts that pentoxifylline attenuated TGF-β1-induced elastogenesis by enhancing phosphorylation of the inhibitory SMAD6.20

Mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 7 (SMAD7) acts as a negative regulator of TGF-β signaling through multiple mechanisms, such as by blocking phosphorylation and recruitment of SMAD2/3 and by inducing degradation of the TGF-β type I receptor.21,22,23 SMAD7 has been demonstrated to protect TGF-β-induced fibrosis in a variety of organs, including kidney, lung, and liver.24,25,26 We recently reported that adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of SMAD7 successfully restored erectile function in mice with cavernous nerve injury through an anti-fibrotic effect.27

In the present study, we determined the effectiveness of the transient overexpression of the SMAD7 gene on the TGF-β1-induced profibrotic responses in primary fibroblasts derived from human PD plaques.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Primary fibroblast culture

Fibroblasts were isolated from human PD plaques as previously described.17,19 Briefly, the plaque tissue was transferred into sterile vials containing Hank's balanced salt solution (GIBCO, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and was washed 3 times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Biopsy tissue was minced into 1-mm2 segments and incubated in a shaker in 12.5 ml Dulbecco's modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 0.06% collagenase A (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 1 h. The cells and tissue fragments were collected by centrifugation (400 g for 5 min), washed in fresh culture medium, and placed in 100-mm cell culture dishes (Falcon-Becton Dickinson Labware, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) under standard cell culture conditions with DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 U ml−1), and streptomycin (100 μg ml−1). The dishes were incubated in a humidified 37°C incubator with 5% CO2. The cells were then characterized as previously described.17,19 Passages five to eight were used for experimentation. We used four cell lines in this study.

Transient transfection

pCMV5 inserted full-length human SMAD7 gene (GenBank ID: NM_005904) was purchased from Addgene (Cambridge, MA, USA). Transient transfections were performed by using hyperbranched poly (ethyleneimine) (25 kDa, PEI25k; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and a PEI25k/pCMV5-Smad7 polyplex was prepared at a weight ratio of 1. The fibroblasts were serum-starved for 24 h and transfected with a 1 μg SMAD7 expression vector. In parallel, an empty PEI25k/pCMV5 vector was used as a control. After transfection, cells were plated and cultured for 48 h in DMEM. The fibroblasts were then treated with 10 ng ml−1 TGF-β1 (RandD Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) for 24 h to detect the protein expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), fibronectin, collagen subtypes, smooth muscle α-actin, and HDAC2, or were treated with TGF-β1 for 1 h to detect the protein expression of phospho-Smad2 (P-Smad2), P-Smad3, total Smad2/3, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1), and cyclin D1 and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assays.

Western blot

Equal amounts of protein from whole-cell extracts (50 μg per lane) were electrophoresed on 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with antibody against PAI-1 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK; 1:400), fibronectin (Abcam; 1:400), collagen I (Abcam; 1:400), collagen IV (Abcam; 1:400), smooth muscle α-actin (Sigma-Aldrich; 1:400), P-Smad2 (s465/467, Cell signaling, Beverly, MA, USA; 1:400), P-Smad3 (s423/425, Cell signaling; 1:400), Smad2/3 (Cell signaling; 1:400), PARP-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA; 1:400), cyclin D1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:400), or β-actin (Abcam; 1:6000). Results were quantified by densitometry.

Hydroxyproline assay

Collagen protein levels were estimated by hydroxyproline determinations as previously described.28 Briefly, aliquots of standard hydroxyproline or fibroblasts samples were hydrolyzed in alkali. The hydrolyzed samples were then mixed with a buffered chloramine-T reagent, and oxidation was allowed to proceed for 25 min at room temperature. The chromophore was then developed with the addition of Ehrlich's reagent, and the absorbance of the reddish-purple complex was measured at 550 nm using a spectrophotometer. Absorbance values were plotted against the concentration of standard hydroxyproline, and the presence of hydroxyproline in fibroblast lysates was determined from the standard curve.

Fluorescent immunocytochemistry

The fibroblasts were cultured on sterile cover glasses (Marienfeld Laboratory, Lauda-Königshofen, Germany) and grown until nearly confluent. The cells were washed 3 times with PBS and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at 4°C and in 100% methanol for 10 min at 4°C. Individual chambers were incubated with an antibody to smooth muscle α-actin (Sigma-Aldrich; 1:300) or Smad2/3 (Cell signaling; 1:200) overnight at 4°C in a moist chamber. After several washes with PBS, the chambers were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated (Zymed Laboratories, South San Francisco, CA, USA; 1:300) or tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate-conjugated (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, PA, USA; 1:300) secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. Mounting medium containing 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA) was applied to the chamber and nuclei were labeled. Signals were visualized, and digital images were obtained with a confocal microscope (FV1000, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) under identical exposure settings. Average fluorescent intensity was measured for every nucleus in the field and averaged for the field with an image analyzer system (National Institutes of Health Image J 1.34; Internet: http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/).

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick-end labeling assay

The TUNEL assay was performed using an ApopTagR Fluorescein In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (S7160, Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA). Nuclei were labeled with DAPI (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± standard error (s.e.) The group comparisons of parametric data were made by a one-way analysis of variance followed by Newman–Keuls post hoc tests. We used the Kruskal–Wallis tests for nonparametric data. We performed statistical analysis with SigmaStat 3.5 software (Systat Software Inc., Richmond, CA, USA). We tested data for normality and variance. P < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

SMAD7 overexpression inhibits extracellular matrix production induced by transforming growth factor-β1 in fibroblasts derived from human Peyronie's disease plaques

Peyronie's disease fibroblasts were transiently transfected with PEI25k/pCMV5-Smad7. Western blot analysis revealed that the treatment of PD fibroblasts with TGF-β1 induced protein expression of extracellular matrix, including PAI-1, fibronectin, collagen I, and collagen IV (P < 0.05 by Kruskal-Wallis tests). The SMAD7 gene profoundly inhibited TGF-β1-induced production of collagen I and collagen IV in PD fibroblasts (P < 0.05 by Kruskal-Wallis tests). Although the SMAD7 gene also decreased production of PAI-1 and fibronectin, it did not yield statistical significance (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

SMAD7 overexpression inhibits TGF-β1-induced extracellular matrix protein production in fibroblasts derived from human Peyronie's disease plaque. Fibroblasts were transfected with an empty PEI25k/pCMV5 vector or a PEI25k/pCMV5-Smad7 polyplex (pSmad7) for 48 h and were then treated with TGF-β1 (10 ng ml−1) for 24 h. (a) A representative Western blot for PAI-1, fibronectin, collagen I, and collagen IV in fibroblasts. (b) Data are presented as the relative density of each protein compared with that of β-actin. Each bar depicts the mean values (± s.e.) from four experiments per group. *P< 0.05 by Kruskal–Wallis tests. PAI-1: plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; PEI: poly (ethyleneimine); TGF-β1: transforming growth factor-β1; SMAD7: decapentaplegic homolog 7; s.e.: standard error.

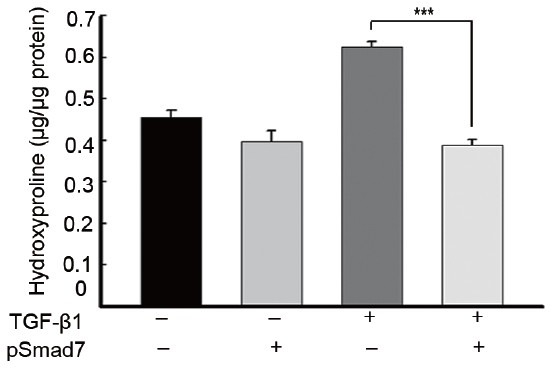

We also determined total collagen content by measuring the amount of hydroxyproline. The SMAD7 gene reduced TGF-β1-induced collagen production in PD fibroblasts (P < 0.001 by ANOVA), which was comparable to the level found in the untreated control (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

SMAD7 overexpression decreases production of hydroxyproline in fibroblasts derived from human Peyronie's disease plaque. Fibroblasts were transfected with an empty PEI25k/pCMV5 vector or a PEI25k/pCMV5-Smad7 polyplex (pSmad7) for 48 h and were then treated with TGF-β1 (10 ng ml−1) for 24h. Each bar depicts the mean values (± s.d.) from four experiments per group. ***P< 0.001 by ANOVA. PEI: poly (ethyleneimine); TGF-β1: transforming growth factor-β1; SMAD7: decapentaplegic homolog 7.

SMAD7 overexpression inhibits transforming growth factor-0β1-induced myofibroblastic differentiation in fibroblasts derived from human Peyronie's disease plaques

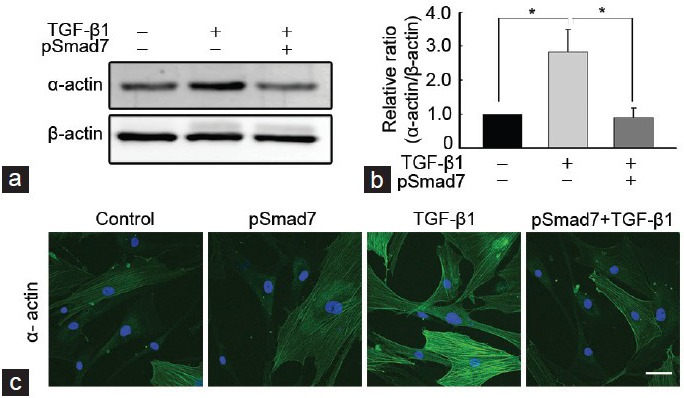

The expression of smooth muscle α-actin, a marker for myofibroblasts, was determined with a Western blot analysis. The treatment of PD fibroblasts with TGF-β1 resulted in an increase in smooth muscle α-actin expression (P < 0.05 by ANOVA), which was substantially reduced after treatment with the SMAD7 gene (P < 0.05 by ANOVA; Figure 3a and 3b). Fluorescent immunocytochemistry revealed that the SMAD7 gene inhibited TGF-β1-stimulated α-actin fiber formation (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

SMAD7 overexpression inhibits TGF-β1-induced myofibroblastic differentiation in fibroblasts derived from human Peyronie's disease plaque. Fibroblasts were transfected with an empty PEI25k/pCMV5 vector or a PEI25k/pCMV5-Smad7 polyplex (pSmad7) for 48 h and were then treated with TGF-β1 (10 ng ml−1) for 24 h. (a) A representative Western blot for smooth muscle α-actin in fibroblasts. Whole-cell extracts were fractionated in a sodium dodecylsulfate-polyacrylamide gel. (b) Data are presented as the relative density of smooth muscle α-actin protein compared with that of β-actin. Each bar depicts the mean values (± s.e.) from four experiments per group. The relative ratio measured in the no treatment group was arbitrary presented as 1. *P< 0.05 by ANOVA. (c) Representative fluorescent immunocytochemistry of fibroblasts with antibody against smooth muscle α-actin. Nuclei were labeled with the DNA dye DAPI. Schale bar = 25 μm. Results were similar from four independent experiments. PEI: poly (ethyleneimine); TGF-β1: transforming growth factor-β1; SMAD7: decapentaplegic homolog 7; DAPI: 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; s.e.: standard error.

SMAD7 overexpression induces apoptosis and blocks cell cycle entry in fibroblasts derived from human Peyronie's disease plaques

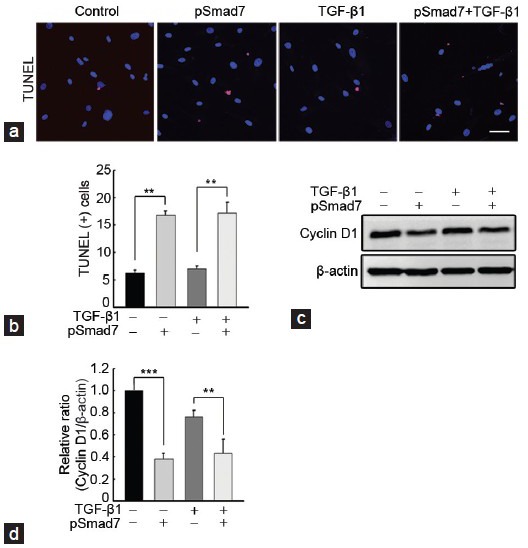

A TUNEL assay showed that the SMAD7 gene profoundly induced apoptosis in PD fibroblasts both in basal and TGF-β1-stimulated conditions (P < 0.01 by ANOVA; Figure 4a and 4b). A Western blot analysis revealed that the treatment of PD fibroblasts with SMAD7 gene decreased expression of cyclin D1, a positive cell cycle regulator, both in basal and TGF-β1-stimulated conditions (P < 0.001 for basal condition and P < 0.01 for stimulated condition by ANOVA; Figure 4c and 4d).

Figure 4.

SMAD7 overexpression induces apoptosis and blocks cell cycle entry in fibroblasts derived from human Peyronie's disease plaque. Fibroblasts were transfected with an empty PEI25k/pCMV5 vector or a PEI25k/pCMV5-Smad7 (pSmad7) polyplex for 48 h and were then treated with TGF-β1 (10 ng ml−1) for 1 h. (a) Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick-end labeling assay. Nuclei were labeled with the DNA dye DAPI. One bar indicates 25 μm. (b) The number of apoptotic cells is presented as a percentage of total cells per field. (c) A representative Western blot for cyclin D1. Whole-cell extracts were fractionated in a sodium dodecylsulfate-polyacrylamide gel. (d) Data are presented as the relative density of each protein compared with that of β-actin. The relative ratio measured in the no treatment group was arbitrary presented as 1. Each bar depicts the mean values (± s.e.) from four experiments per group. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by ANOVA. PEI: poly (ethyleneimine); TGF-β1: transforming growth factor-β1; SMAD7: decapentaplegic homolog 7; DAPI: 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

SMAD7 overexpression inhibits phosphorylation, and nuclear translocation of decapentaplegic homolog 2/3 induced by transforming growth factor-β1 in fibroblasts derived from human Peyronie's disease plaques

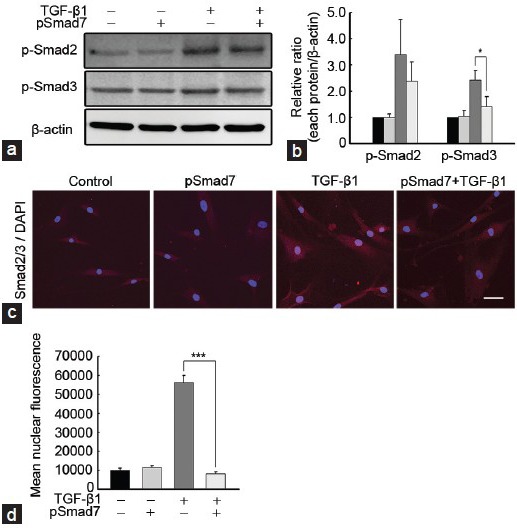

The treatment of PD fibroblasts with TGF-β1 resulted in an increase in phosphorylation of Smad3, which was substantially inhibited by preincubation with the SMAD7 gene (P < 0.05 by ANOVA; Figure 5a and 5b). Although the SMAD7 gene also decreased TGF-β1-stimulated SMAD2 phosphorylation, it did not yield statistical significance (Figure 5a and 5b). In order to evaluate whether SMAD7 is involved for TGF-β1-induced nuclear shuttling of Smad2/3, we performed fluorescent immunocytochemistry with antibody against Smad2/3. The SMAD7 gene reduced TGF-β1-induced nuclear accumulation of the Smad proteins (P < 0.001 by Kruskal-Wallis tests; Figure 5c and 5d).

Figure 5.

SMAD7 overexpression suppresses TGF-β1-induced SMAD2 and SMAD3 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation in fibroblasts derived from human Peyronie's disease plaque. Fibroblasts were transfected with an empty PEI25k/pCMV5 vector or a PEI25k/pCMV5-Smad7 polyplex (pSmad7) for 48 h and were then treated with TGF-β1 (10 ng ml−1) for 1 h. (a) A representative Western blot for P-Smad2, P-Smad3, and total SMAD2/3. Whole-cell extracts were fractionated in a sodium dodecylsulfate-polyacrylamide gel. (b) Data are presented as the ratio of phosphorylated protein to total protein. The relative ratio measured in the no treatment group was arbitrary presented as 1. Each bar depicts the mean values (± s.e.) from four experiments per group. *P < 0.05 by ANOVA. (c) Representative fluorescent immunocytochemistry of primary human fibroblasts with antibody against total SMAD2/3. Nuclei were labeled with the DNA dye DAPI. Schale bar = 25 μm. (d) Nuclear fluorescence intensity was quantified for all cells. Each bar depicts the mean values (± s.e.) from four experiments per group. ***P < 0.001 by Kruskal–Wallis tests. PEI: poly (ethyleneimine); TGF-β1: transforming growth factor-β1; SMAD7: decapentaplegic homolog 7; P-Smad2: phospho-Smad2; DAPI: 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; s.e.: standard error.

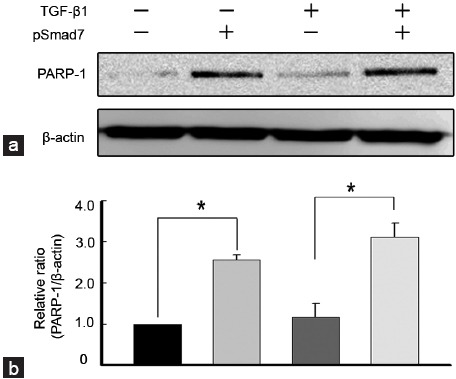

SMAD7 overexpression increases poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 expression in fibroblasts derived from human Peyronie's disease plaques

A Western blot analysis showed that the SMAD7 gene increased the expression of PARP-1, which is known to terminate Smad-mediated transcription, in PD fibroblasts both in basal and TGF-β1-stimulated conditions (P < 0.05 by Kruskal–Wallis tests; Figure 6).

Figure 6.

SMAD7 overexpression increases PARP-1 expression in fibroblasts derived from human Peyronie’s disease plaque. Fibroblasts were transfected with an empty PEI25k/pCMV5 vector or a PEI25k/pCMV5-Smad7 polyplex (pSmad7) for 48 h and were then treated with TGF-β1 (10 ng ml–1) for 1 h. (a) A representative Western blot for PARP-1. Whole-cell extracts were fractionated in a sodium dodecylsulfate-polyacrylamide gel. (b) Data are presented as the relative density of each protein compared with that of β-actin. The relative ratio measured in the no treatment group was arbitrary presented as 1. Each bar depicts the mean values (± s.e.) from four experiments per group. *P < 0.05 by Kruskal–Wallis tests. PEI: poly (ethyleneimine); TGF-β1: transforming growth factor-β1; SMAD7: decapentaplegic homolog 7; PARP-1: poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1; s.e.: standard error.

DISCUSSION

We showed here that the overexpression of the SMAD7 gene decreased the TGF-β1-induced accumulation of extracellular matrix and production of hydroxyproline in human PD fibroblasts by inhibiting TGF-β1-induced myofibroblastic differentiation and by accelerating apoptosis and blocking cell cycle entry. Furthermore, SMAD7 blocked TGF-β signaling through inhibition of the phosphorylation and nuclear shuttling of SMAD3 and/or SMAD2, and up-regulation of PARP-1 that is known to terminate Smad-mediated transcription.

It was first reported in mice that overexpression of SMAD7 prevented bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis.25 In the present study, SMAD7 overexpression inhibited TGF-β1-induced production of collagen I and collagen IV as well as hydroxyproline in PD fibroblasts in vitro. This finding is similar to the results from ours showing that adenovirus-mediated SMAD7 gene transfer into the penis significantly decreased the production of extracellular matrix proteins in mice with cavernous nerve injury in vivo.27 In a tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis model, overexpression of SMAD7 attenuated a fibrogenic response,26 whereas down-regulation of SMAD7 accelerated liver fibrosis.29 These findings suggest a protective role of SMAD7 in suppressing TGF-β-mediated fibrosis in a variety of organs.

Transforming growth factor-β-mediated fibrotic responses are initiated by activation of SMAD2 and SMAD3 upon ligand binding, which in turn induces myofibroblastic differentiation and promotes the synthesis of extracellular matrix proteins.30 In the present study, overexpression of SMAD7 blocked TGF-β1-induced SMAD3 phosphorylation and the nuclear accumulation of Smad2/3 proteins. Moreover, both Western blot analysis and fluorescent immunocytochemistry revealed that SMAD7 overexpression quashed TGF-β1-induced myofibroblastic differentiation. In the agreement with this finding, overexpression of SMAD7 is known to inhibit SMAD2/3 phosphorylation and protect against activation of hepatic stellate cells into myofibroblasts,31 whereas repression of SMAD7 promotes SMAD2/3 phosphorylation and activates hepatic stellate cells.32 It was also reported that SMAD7 gene transfer substantially inhibited SMAD2/3 activation and attenuated myofibroblast accumulation in a rat model of renal fibrosis.33 These findings suggest that the inhibition of SMAD2/3 activity is the main mechanism responsible for SMAD7-mediated myofibroblastic differentiation and subsequent accumulation of extracellular matrix proteins.

Despite the relatively well-known effect of SMAD7 on transdifferentiation of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts, little data are as yet available in regard to its effect on apoptosis of fibroblasts. In the present study, treatment of PD fibroblast with SMAD7 gene induced apoptosis of fibroblasts in both basal and TGF-β1-stimulated conditions. Mesangial cell proliferation is a key feature of glomerular scarring and end-stage renal disease, and overexpression of SMAD7 is known to increase caspase-3 activity and promote mesangial cell apoptosis.34 SMAD7 is reported to activate caspase-8 and to induce apoptosis in human breast cancer cell culture in vitro and in xenograft model in vivo.35 In the present study, the SMAD7 gene also decreased expression of cyclin D1, a positive cell cycle regulator, suggesting SMAD7 can regulate fibroblast proliferation by modulating cell cycle.

Another mechanism by which overexpression of SMAD7 attenuates fibrotic responses in PD fibroblasts may be attributable to increase in expression of PARP-1. It was reported that PARP-1 mediates poly (ADP-ribosyl) ation (PARylation) and regulates transcription factors.36 PARP-1 is known to dissociate SMAD complexes from DNA through PARylation of SMAD3 and SMAD4, which terminates Smad-mediated transcription.37 Additional studies are necessary to document the exact functional roles of PARP-1 in the pathogenesis of PD.

In the present study, we for the first time documented that inhibition of the TGF-β pathway using the SMAD7 gene has an anti-fibrotic effect in human PD fibroblasts in vitro, which warrants further studies in PD animal models in vivo.

In summary, overexpression of the SMAD7 gene attenuated TGF-β1-induced extracellular matrix production and transdifferentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts by blocking activation of SMAD2/3 pathway and possibly by inhibiting Smad-mediated transcription through an up-regulation of PARP-1. Inhibition of the TGF-β pathway by use of SMAD7 may be a viable therapeutic strategy for the treatment of PD.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

SHP, DSR, JKR, and JKS participated in the design of the study. MJC and KMS carried out Western blot analysis. JMP carried out hydroxyproline assay. MHK carried out immunocytochemistry. KDK carried out TUNEL assay. MJC performed statistical analysis. SHP and DSR conceived of the study. MJC and JKR drafted manuscript. JKS critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grant NO. 2011-0015771 (Ji-Kan Ryu) from the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation funded by the Korea government (Ministry for Education, Science, and Technology).

REFERENCES

- 1.Schwarzer U, Sommer F, Klotz T, Braun M, Reifenrath B, et al. The prevalence of Peyronie's disease: results of a large survey. BJU Int. 2001;88:727–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-4096.2001.02436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mulhall JP, Creech SD, Boorjian SA, Ghaly S, Kim ED, et al. Subjective and objective analysis of the prevalence of Peyronie's disease in a population of men presenting for prostate cancer screening. J Urol. 2004;171:2350–3. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000127744.18878.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jarow JP, Lowe FC. Penile trauma: an etiologic factor in Peyronie's disease and erectile dysfunction. J Urol. 1997;158:1388–90. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)64222-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devine CJ, Jr, Somers KD, Jordan SG, Schlossberg SM. Proposal: trauma as the cause of the Peyronie's lesion. J Urol. 1997;157:285–90. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)65361-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hauck EW, Diemer T, Schmelz HU, Weidner W. A critical analysis of nonsurgical treatment of Peyronie's disease. Eur Urol. 2006;49:987–97. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kadioglu A, Akman T, Sanli O, Gurkan L, Cakan M, et al. Surgical treatment of Peyronie's disease: a critical analysis. Eur Urol. 2006;50:235–48. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gelbard M, Lipshultz LI, Tursi J, Smith T, Kaufman G, et al. Phase 2b study of the clinical efficacy and safety of collagenase Clostridium histolyticum in patients with Peyronie disease. J Urol. 2012;187:2268–74. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gelbard M, Goldstein I, Hellstrom WJ, McMahon CG, Smith T, et al. Clinical efficacy, safety and tolerability of collagenase Clostridium histolyticum for the treatment of peyronie disease in 2 large double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled phase 3 studies. J Urol. 2013;190:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.01.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hellstrom WJ, Kendirci M, Matern R, Cockerham Y, Myers L, et al. Single-blind, multicenter, placebo controlled, parallel study to assess the safety and efficacy of intralesional interferon alpha-2B for minimally invasive treatment for Peyronie's disease. J Urol. 2006;176:394–8. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00517-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Safarinejad MR, Asgari MA, Hosseini SY, Dadkhah F. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of pentoxifylline in early chronic Peyronie's disease. BJU Int. 2010;106:240–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.09041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biagiotti G, Cavallini G. Acetyl-L-carnitine vs tamoxifen in the oral therapy of Peyronie's disease: a preliminary report. BJU Int. 2001;88:63–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine LA, Merrick PF, Lee RC. Intralesional verapamil injection for the treatment of Peyronie's disease. J Urol. 1994;151:1522–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35291-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shirazi M, Haghpanah AR, Badiee M, Afrasiabi MA, Haghpanah S. Effect of intralesional verapamil for treatment of Peyronie's disease: a randomized single-blind, placebo-controlled study. Int Urol Nephrol. 2009;41:467–71. doi: 10.1007/s11255-009-9522-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez-Cadavid NF, Magee TR, Ferrini M, Qian A, Vernet D, et al. Gene expression in Peyronie's disease. Int J Impot Res. 2002;14:361–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Sakka AI, Hassoba HM, Pillarisetty RJ, Dahiya R, Lue TF. Peyronie's disease is associated with an increase in transforming growth factor-beta protein expression. J Urol. 1997;158:1391–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haag SM, Hauck EW, Szardening-Kirchner C, Diemer T, Cha ES, et al. Alterations in the transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta pathway as a potential factor in the pathogenesis of Peyronie's disease. Eur Urol. 2007;51:255–61. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piao S, Choi MJ, Tumurbaatar M, Kim WJ, Jin HR, et al. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-ß type I receptor kinase (ALK5) inhibitor alleviates profibrotic TGF-ß1 responses in fibroblasts derived from Peyronie's plaque. J Sex Med. 2010;7:3385–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryu JK, Piao S, Shin HY, Choi MJ, Zhang LW, et al. IN-1130, a novel transforming growth factor-beta type I receptor kinase (activin receptor-like kinase 5) inhibitor, promotes regression of fibrotic plaque and corrects penile curvature in a rat model of Peyronie's disease. J Sex Med. 2009;6:1284–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryu JK, Kim WJ, Choi MJ, Park JM, Song KM, et al. Inhibition of histone deacetylase 2 mitigates profibrotic TGF-ß1 responses in fibroblasts derived from Peyronie's plaque. Asian J Androl. 2013;15:640–5. doi: 10.1038/aja.2013.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin G, Shindel AW, Banie L, Ning H, Huang YC, et al. Pentoxifylline attenuates transforming growth factor-beta1-stimulated elastogenesis in human tunica albuginea-derived fibroblasts part 2: interference in a TGF-beta1/Smad-dependent mechanism and downregulation of AAT1. J Sex Med. 2010;7:1787–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakao A, Afrakhte M, Morén A, Nakayama T, Christian JL, et al. Identification of Smad7, a TGFbeta-inducible antagonist of TGF-beta signalling. Nature. 1997;389:631–5. doi: 10.1038/39369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lebrun JJ, Takabe K, Chen Y, Vale W. Roles of pathway-specific and inhibitory Smads in activin receptor signaling. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:15–23. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.1.0218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kavsak P, Rasmussen RK, Causing CG, Bonni S, Zhu H, et al. Smad7 binds to Smurf2 to form an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets the TGF beta receptor for degradation. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1365–75. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00134-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fukasawa H, Yamamoto T, Togawa A, Ohashi N, Fujigaki Y, et al. Down-regulation of Smad7 expression by ubiquitin-dependent degradation contributes to renal fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8687–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400035101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakao A, Fujii M, Matsumura R, Kumano K, Saito Y, et al. Transient gene transfer and expression of Smad7 prevents bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis in mice. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:5–11. doi: 10.1172/JCI6094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dooley S, Hamzavi J, Ciuclan L, Godoy P, Ilkavets I, et al. Hepatocyte-specific Smad7 expression attenuates TGF-beta-mediated fibrogenesis and protects against liver damage. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:642–59. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song KM, Chung JS, Choi MJ, Jin HR, Yin GN, et al. Effectiveness of intracavernous delivery of adenovirus encoding Smad7 gene on erectile function in a mouse model of cavernous nerve injury. J Sex Med. 2014;11:51–63. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reddy GK, Enwemeka CS. A simplified method for the analysis of hydroxyproline in biological tissues. Clin Biochem. 1996;29:225–9. doi: 10.1016/0009-9120(96)00003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamzavi J, Ehnert S, Godoy P, Ciuclan L, Weng H, et al. Disruption of the Smad7 gene enhances CCI4-dependent liver damage and fibrogenesis in mice. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:2130–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00262.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wynn TA. Common and unique mechanisms regulate fibrosis in various fibroproliferative diseases. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:524–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI31487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dooley S, Hamzavi J, Breitkopf K, Wiercinska E, Said HM, et al. Smad7 prevents activation of hepatic stellate cells and liver fibrosis in rats. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:178–91. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00666-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bian EB, Huang C, Wang H, Chen XX, Zhang L, et al. Repression of Smad7 mediated by DNMT1 determines hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis in rats. Toxicol Lett. 2014;224:175–85. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hou CC, Wang W, Huang XR, Fu P, Chen TH, et al. Ultrasound-microbubble-mediated gene transfer of inducible Smad7 blocks transforming growth factor-beta signaling and fibrosis in rat remnant kidney. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:761–71. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62297-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okado T, Terada Y, Tanaka H, Inoshita S, Nakao A, et al. Smad7 mediates transforming growth factor-beta-induced apoptosis in mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1178–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2002.kid583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong S, Kim HY, Kim J, Ha HT, Kim YM, et al. Smad7 protein induces interferon regulatory factor 1-dependent transcriptional activation of caspase 8 to restore tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-mediated apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:3560–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.400408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim MY, Zhang T, Kraus WL. Poly (ADP-ribosyl) ation by PARP-1: ‘PAR-laying’ NAD+into a nuclear signal. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1951–67. doi: 10.1101/gad.1331805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lönn P, van der Heide LP, Dahl M, Hellman U, Heldin CH, et al. PARP-1 attenuates Smad-mediated transcription. Mol Cell. 2010;40:521–32. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]