Abstract

The challenge facing many fibrotic lung diseases is that these conditions usually present late, often after several decades of repetitive alveolar epithelial injury, during which functional alveolar units are gradually obliterated and replaced with nonfunctional connective tissue. The resulting fibrosis is often progressive and, in the case of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), invariably leads to respiratory insufficiency and, ultimately, the premature death of affected individuals. Recent years have seen a greater appreciation of the relative importance of chronic inflammation as a driver of fibrotic responses. Current evidence suggests that IPF arises as a result of repetitive epithelial injury and a highly aberrant wound healing response in genetically susceptible and aged individuals. Nonspecific anti-inflammatory agents offer no clinical benefit, but the potential contribution of maladaptive immune responses in determining outcome is gaining increasing recognition. The importance of key differences in the tissue-regenerative potential in young versus aged individuals is also beginning to be more fully appreciated. Moreover, there is considerable overlap in the mechanisms underlying tissue repair and cancer, and patients with IPF are at heightened risk of developing lung cancer. Progressive fibrosis and cancer may therefore represent the extremes of a highly dysregulated tissue injury response. This brief review focuses on some of this evidence and on our current understanding of abnormal tissue repair responses after chronic epithelial injury in the specific context of IPF.

Keywords: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, pulmonary fibrosis, lung injury, cancer, myofibroblast

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: The Most Rapidly Progressive of All Fibrotic Conditions

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is the most rapidly progressive of all fibrotic conditions, with a dismal median survival of just 3 years from diagnosis. Our understanding of the key pathomechanisms underlying the development of IPF is incomplete, but current hypotheses propose that this condition arises as a result of repetitive epithelial injury leading to a highly aberrant wound healing response in genetically susceptible and aged individuals (reviewed in ref. 1). The classical histopathological pattern of IPF, usual interstitial pneumonia, is characterized by evidence of patchy epithelial damage, type 2 pneumocyte hyperplasia, abnormal proliferation of mesenchymal cells, varying degrees of fibrosis, and extensive deposition of collagen and other extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins. Fibroblast foci, the hallmark lesions of usual interstitial pneumonia, are commonly observed underlying the injured epithelium. These lesions comprise accumulations of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts embedded within an extensive and highly crosslinked collagen-rich ECM and are thought to represent the leading edge of the fibrotic process.

The last decade has seen a greater appreciation of the relative importance of chronic inflammation in influencing outcome: Whereas chronic inflammation is likely to be important in the development of pulmonary fibrosis in sarcoidosis, systemic sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis, IPF is felt to be perpetuated by a highly aberrant wound healing response after chronic repetitive injury. Indeed, the recent landmark PANTHER-IPF (Prednisone, Azathioprine, N-acetylcysteine: A Study That Evaluates Response in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis) trial demonstrated that standard nonspecific immunotherapy (a combination of prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine) offers no clinical benefit but, rather, increases the risk for death and hospitalization in patients with mild to moderate lung function impairment (2). In contrast, recent evidence suggests a key role for pathologic adaptive immune responses, including dysregulated T- and B-cell responses (3, 4), in influencing IPF progression and outcome, raising the possibility that mechanistically focused immunotherapy may be more efficacious (5). This evidence recently paved the way for a phase 2 trial (Autoantibody Reduction Therapy in Patients With Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis [ART-IPF]) aimed at reducing autoantibody production in IPF, using the B-cell-targeted monoclonal antibody, rituximab.

The abnormal wound healing response in IPF is felt to be perpetuated by a highly aberrant epithelial-mesenchymal cross-talk that drives the excessive activation of resident or recruited myofibroblast precursors. The mechanism or mechanisms underlying this dysregulated epithelial-mesenchymal cross-talk are beginning to come to light, with current evidence suggesting critical roles for potent fibrogenic (e.g., transforming growth factor β [TGF-β], platelet-derived growth factor, etc.) and proapoptotic (e.g., Ang II, FasL, etc.) factors acting through both autocrine and paracrine mechanisms. Moreover, the importance of the abnormal ECM itself in contributing both directly and indirectly to aberrant cellular phenotypes in pulmonary fibrosis is currently the focus of much attention (6). Alterations in ECM composition, mechanical properties, and bound bioactive components (including matricellular proteins and growth factors) are now emerging as being critically involved in influencing fibroblast and myofibroblast function, as well as epithelial cell fate. A detailed review of this “hot topic” in fibrosis research is beyond the scope of this brief review, but readers are referred to an excellent recent workshop report by key investigators in this area (7).

Evidence for a genetic basis to IPF is also now substantial (reviewed in ref. 8), with current data strongly supporting the notion that susceptibility to IPF involves a combination of polymorphisms related to epithelial cell injury, host defense, DNA repair, and wound healing. Moreover, some of these variants are associated similarly with the development of sporadic and familial forms of this condition, pointing to a potential common genetic basis for the development of pulmonary fibrosis. Global gene expression profiling studies have also been highly informative and similarly revealed that IPF displays a unique gene expression signature involving genes associated with ECM synthesis and turnover, smooth muscle markers, growth factors, genes encoding complement, immunoglobulins, and chemokines, as well as genes associated with the reactivation of developmental pathways (9–11). Targeted and global epigenomic studies have further highlighted the importance of epigenetic mechanisms in determining gene transcriptional profiles in IPF. Important roles for changes in DNA methylation, histone modifications, and microRNAs have been identified (for an excellent recent review, please see ref. 12).

The exact triggers that initiate the fibrotic response in the specific context of IPF remain enigmatic, but there is now increasing evidence supporting roles for chronic exposure to cigarette smoke, microaspiration, and possibly viral infection. The unfolded protein response, or endoplasmic reticulum stress, a stereotypical protective reaction that can mitigate the consequences of accumulated unfolded or poorly folded proteins, has also been implicated in the context of familial pulmonary fibrosis associated with specific mutations in surfactant proteins, as well as in sporadic IPF (13). In terms of the influence of aging, telomere attrition and cellular senescence are also likely to be key drivers of the abnormal reparative process in IPF, a disease that usually only presents in aged individuals. Indeed, several recent studies performed in aged experimental mice provide support for the notion that both aging and epithelial senescence are associated with an exaggerated fibrotic response to bleomycin injury (14). In contrast, the role of telomere attrition in IPF has been more challenging to decipher, with different studies reporting different estimates for the incidence of telomere shortening, although this may be reflective of the different IPF populations studied. Moreover, experimental evidence is still lacking to explain how shortened telomeres might affect the development of fibrosis, although the impairment of tissue repair and regeneration of the alveolar epithelium may conceivably be important factors. For a more detailed discussion of the influence of aging in IPF, readers are referred to excellent recent articles (15, 16).

Cellular Origin of Myofibroblasts

Whereas epithelial injury and dysregulated epithelial regeneration are key events involved in initiating and sustaining IPF, current evidence strongly points to fibroblasts and highly synthetic and contractile myofibroblasts as the key effector cells responsible for excessive matrix synthesis and deposition in IPF, as well as many other fibrotic conditions (reviewed in ref. 1). The identification of the cellular origin of these (myo)fibroblasts in tissue fibrosis is an area of ongoing research interest and lively debate. Although the traditional view that a significant proportion of myofibroblasts in pulmonary fibrosis are likely derived from the local recruitment, proliferation, and differentiation of resident lung fibroblasts has remained largely unchallenged, elegant lineage tracing studies in animal models have identified several additional potential cellular sources, including circulating bone marrow-derived fibrocytes, epithelial cells (via epithelial mesenchymal transition [EMT]), pleural mesothelial cells (via mesothelial to mesenchymal transition), endothelial cells (via endothelial to mesenchymal transition), and most recently, forkhead box D1 (FOXD1)-progenitor-derived pericytes (17), although this latter observation was not a universal finding (18). The extrapolation of these experimental findings to IPF is not straightforward, as animal models of pulmonary fibrosis may not faithfully recapitulate this aspect of the fibrotic response in humans. A consensus is also beginning to emerge that rather than contributing to the expansion of collagen-synthesizing myofibroblasts, the contribution of nonmesenchymal cell types may be indirect. Indeed, in terms of the influence of EMT on the fibrotic response, there is now increasing recognition that epithelial cells undergoing EMT or an EMT-like process likely contribute to the aberrant epithelial-mesenchymal crosstalk that promotes fibrogenesis, rather than act as a significant source of myofibroblasts (19).

TGF-β1: A Central Mediator in IPF

More than 20 years of extensive research has established an undeniable role for TGF-β signaling in pulmonary fibrosis and many other fibrotic disorders. TGF-β is a potent promoter of ECM production and exerts its profibrotic effects by inducing fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation, by promoting myofibroblast survival, and by inhibiting matrix degradation pathways. Multiple approaches that disrupt TGF-β signaling through direct cytokine inhibition, Smad3 knockout, TGF-βRI/Activin receptor-like kinase 5 receptor knockout, or antibody neutralization have offered protection in preclinical models of pulmonary fibrosis (reviewed in ref. 1). However, liabilities associated with disrupting the key homeostatic anti-inflammatory and tumor suppressor functions of TGF-β, especially in patients with IPF who are at a heightened risk of developing lung cancer, remain a major concern, although an antibody that neutralizes all mammalian TGF-β isoforms (GC1008; Genzyme, Cambridge, MA) has now completed early clinical safety evaluation (http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00125385).

In contrast, approaches that target specific latent TGF-β activation mechanisms during fibrogenesis are considered potentially lower risk. In this regard, there has been much interest in the αvβ6 integrin as a major target for interfering with latent TGF-β activation and subsequent signaling in multiple fibrotic indications, including IPF. This integrin is expressed at low levels in healthy adult tissues but is strongly up-regulated on the epithelium in response to tissue injury and in fibrosis. Its activates latent TGF-β by changing the conformation of the latent TGF-β complex by transmitting cell traction forces and requires association of the latent complex with a mechanically resistant ECM. Moreover, TGF-β itself is a potent inducer of epithelial cell αvβ6 expression and may therefore generate a positive feed-forward loop, which in turn accelerates the pace of fibrosis. This loop may in turn become self-perpetuating as the ECM continues to be deposited and stiffen as a result of sustained TGF-β signaling. In terms of developing new antifibrotic strategies, the potential importance of this pathway in promoting tissue fibrosis has now been demonstrated in multiple animal models (20–22), and the results of a phase 2 trial of a humanized anti-αvβ6 antibody (STX-100; Biogen Idec, Cambridge, MA) in patients with IPF (http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01371305) are eagerly awaited.

Cross-Talk between Coagulation and TGF-β Signaling

Research in our center has focused on deciphering the potential profibrotic role of intraalveolar coagulation, another key feature of several fibrotic lung diseases, including IPF. This research revealed a key role for the high-affinity thrombin receptor, proteinase-activated receptor 1 (PAR-1), in mediating the interplay between coagulation and abnormal lung injury responses (23). Studies involving primary human lung fibroblasts demonstrated that activation of PAR-1 by thrombin or coagulation factor Xa promotes platelet-derived growth factor-mediated fibroblast proliferation and increased ECM synthesis and also influences the production of potent pro-inflammatory chemokines, including chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (24–27). Studies aimed at identifying the source and the nature of the procoagulant activity responsible for activating PAR-1 in the setting of pulmonary fibrosis revealed that several zymogens of the extrinsic coagulation cascade are locally up-regulated and activated in the lungs of patients with IPF (28). PAR-1 was found to be highly expressed by lung fibroblasts and also, albeit to a lesser extent, by the hyperplastic epithelium overlying IPF fibroblast foci (27). We and others further uncovered a central role for PAR-1 in mediating the cross-talk between the coagulation cascade and the TGF-β pathway with the discovery that PAR-1 signaling promotes the integrin αvβ6- and αvβ5-dependent activation of latent TGF-β1 by epithelial cells and fibroblasts, respectively (28, 29). Interestingly, PAR-1 signaling responses have also been strongly implicated in other fibrotic conditions, including the liver, kidney, and heart (30), suggesting that PAR-1 may represent a potential “core fibrosis pathway,” according to the recent criteria proposed in Reference 31.

Taken together, these observations support the scientific rationale for targeting PAR-1-dependent coagulation signaling responses in the context of fibrosis, using recently developed PAR-1 antagonists. The first such agent, SCH530348 (Vorapaxar), was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as a first-in-class antiplatelet agent for the treatment and prevention of atherothrombotic events in patients with previous myocardial infarction and peripheral artery disease. Such an approach may provide a more selective mechanism for targeting deleterious coagulation signaling than broad-spectrum anticoagulant approaches. This is worth considering in light of the recent ACE-IPF trial, a phase 3 multicenter, placebo-controlled randomized trial of orally dosed warfarin in IPF, which was halted early because of excess risk for mortality in the warfarin treatment group (32). The study findings suggest this excess mortality was attributable to a worsening in respiratory symptoms. The underlying reasons for these unexpected findings are not fully understood, but the ACE-IPF investigators proposed that alveolar hemorrhage, which was not measured in the study, or the unexpected detrimental effects associated with inhibiting all vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors (factors II, VII, IX, and X) and critical anticoagulants (protein C and protein S) may have been contributory factors. The potential effects on the protein C axis might be particularly important because activated protein C exerts important endothelial barrier protective effects that may be indispensable in the setting of a condition driven by repetitive alveolar injury such as IPF. Although the ACE-IPF trial strongly argues against systemic depletion of vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors in IPF, the potential for local anticoagulation strategies remains to be fully explored. In this regard, there have been some encouraging data from safety and tolerability studies of inhaled heparin in IPF that revealed significant inhibition of local intraalveolar coagulation without heparin-related adverse effects (33).

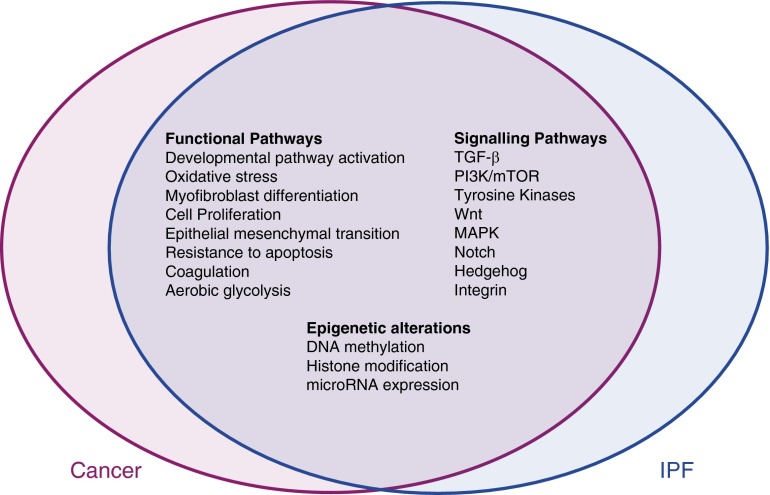

Common Features of IPF and Cancer

As well as being associated with increased lung cancer risk (34), IPF shares a number of common features with cancer (Figure 1 and reviewed in Reference 35). Most notable is the unremitting progression of IPF, which is similar to that of cancer, but there is also evidence of common pathogenic events, with several functional responses, signaling pathways, genetic changes, and epigenetic signatures in IPF showing a degree of overlap with those observed in lung cancer (36, 37). Moreover, although current evidence suggests that fibroblast foci likely arise as a result of a reactive, rather than a malignant, process (38), IPF fibroblasts exhibit an invasive phenotype (39) and may therefore be able to invade the ECM, including the alveolar basement membrane, in a manner akin to metastatic tumor cells. IPF has also recently been reported to be associated with increased (18)F-deoxyglucose uptake, a marker of aerobic glycolysis in tumors, with the highest site of maximal uptake corresponding to areas of reticulation/honeycomb on high-resolution computed tomography (40). The mechanistic overlap between IPF and cancer has raised the possibility that existing oncology drugs or assets might be suitable or “repositioned” for the treatment of IPF. Indeed, one such agent, Ofev/nintedanib, a triple angiokinase inhibitor that simultaneously acts on vascular endothelial growth factor receptors, platelet-derived growth factor receptors, and fibroblast growth factor receptors, has recently shown promise in reducing the decline in FVC in two replicate 52-week randomized, double-blind, phase 3 IPF trials (INPULSIS-1 and INPULSIS-2 [41]). The US Food and Drug Administration granted simultaneous approval for Ofev/nintedanib and Esbriet/pirfenidone in October 2014 as the first disease-specific therapies for IPF. Although the exact mechanism of action of Esbriet is not fully understood, and the two agents have not been compared side by side, both drugs appear to be equally effective in slowing disease progression.

Figure 1.

Mechanistic overlap between idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and cancer.

In terms of other signaling pathways that have been strongly implicated in both cancer and IPF, the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3 (PI3) kinase family of heterodimeric lipid kinases has also been the focus of recent attention. This family of kinases is involved in integrating the crosstalk from a variety of stimuli, including tyrosine kinase receptors, G-protein-coupled receptors, and activated Ras (42). Activation of PI3 kinase leads to activation of Akt (protein kinase B), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), and downstream protein kinases and thereby controls key cellular processes including growth, cell cycle progression, proliferation, metabolism, and synthetic pathways. Dysregulated PI3-kinase signaling as a result of low activity of the tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homolog has been implicated in myofibroblast differentiation and in maintaining the fibroproliferative phenotype of IPF fibroblasts (43, 44). A proof-of-mechanism study of the pan-PI3 kinase/mTOR inhibitor, GSK2126458, is currently recruiting patients (http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01725139). Other oncology agents under investigation in IPF include the rapalog sirolimus (http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01462006) and vismodegib, which exerts antineoplastic activity by inhibiting the hedgehog pathway (http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT02168530).

Summary and Concluding Remarks

The last decade has seen major advances in our understanding of the mechanisms leading to abnormal repair and fibrosis after chronic epithelial injury. There is now mounting evidence that IPF is shaped by complex interplay between repetitive epithelial injury, genetic susceptibility, epigenetic alterations, and the aging process. There is also increasing recognition that progressive fibrosis can become a self-sustaining and potentially inflammation-independent process, in particular in patients with advanced disease. In this regard, there is strong support that the TGF-β pathway and altered ECM play key roles in perpetuating the fibrogenic response via multiple feed-forward loops. The interplay between TGF-β signaling and intraalveolar coagulation also likely contributes to perpetuating fibrotic responses within fibroblast foci, although other danger signals activated after tissue injury are also likely to contribute. Finally, although IPF does not metastasize and may not be driven by somatic mutations, there is increasing recognition that IPF shares many cancer-like features, so that existing cancer agents may represent unique opportunities for developing much-needed effective therapeutic interventions for this devastating condition.

Footnotes

Supported by the Wellcome Trust (GR071124MA), the M.B.Ph.D. program of University College London, the Rockefeller Fund, the British Lung Foundation (F07/6), the Medical Research Council UK (G0800340 and G0800265), and the European Community’s Seventh Framework Program (FQ7/2007–2013) under grant agreement HEALTH-F2–2007–202224 eurIPFnet.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Datta A, Scotton CJ, Chambers RC. Novel therapeutic approaches for pulmonary fibrosis. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163:141–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raghu G, Anstrom KJ, King TE, Jr, Lasky JA, Martinez FJ Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Clinical Research Network. Prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine for pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1968–1977. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xue J, Kass DJ, Bon J, Vuga L, Tan J, Csizmadia E, Otterbein L, Soejima M, Levesque MC, Gibson KF, et al. Plasma B lymphocyte stimulator and B cell differentiation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients. J Immunol. 2013;191:2089–2095. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herazo-Maya JD, Noth I, Duncan SR, Kim S, Ma SF, Tseng GC, Feingold E, Juan-Guardela BM, Richards TJ, Lussier Y, et al. Peripheral blood mononuclear cell gene expression profiles predict poor outcome in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:205ra136. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vuga LJ, Tedrow JR, Pandit KV, Tan J, Kass DJ, Xue J, Chandra D, Leader JK, Gibson KF, Kaminski N, et al. C-X-C motif chemokine 13 (CXCL13) is a prognostic biomarker of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:966–974. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1592OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker MW, Rossi D, Peterson M, Smith K, Sikström K, White ES, Connett JE, Henke CA, Larsson O, Bitterman PB. Fibrotic extracellular matrix activates a profibrotic positive feedback loop. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:1622–1635. doi: 10.1172/JCI71386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thannickal VJ, Henke CA, Horowitz JC, Noble PW, Roman J, Sime PJ, Zhou Y, Wells RG, White ES, Tschumperlin DJ. Matrix biology of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a workshop report of the national heart, lung, and blood institute. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:1643–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spagnolo P, Grunewald J, du Bois RM. Genetic determinants of pulmonary fibrosis: evolving concepts. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:416–428. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selman M, Pardo A, Kaminski N. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: aberrant recapitulation of developmental programs? PLoS Med. 2008;5:e62. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selman M, Pardo A, Barrera L, Estrada A, Watson SR, Wilson K, Aziz N, Kaminski N, Zlotnik A. Gene expression profiles distinguish idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis from hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:188–198. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200504-644OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaminski N, Zuo F, Cojocaro G, Yakhini Z, Ben-Dor A, Morris D, Sheppard D, Pardo A, Selman M, Heller RA. Use of oligonucleotide microarrays to analyze gene expression patterns in pulmonary fibrosis reveals distinct patterns of gene expression in mice and humans. Chest. 2002;121(3, Suppl):31S–32S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang IV, Schwartz DA. Epigenetics of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Transl Res. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2014.03.011. [online ahead of print] 31 Mar 2014; DOI: 10.1016/j.trsl.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korfei M, von der Beck D, Henneke I, Markart P, Ruppert C, Mahavadi P, Ghanim B, Klepetko W, Fink L, Meiners S, et al. Comparative proteome analysis of lung tissue from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) and organ donors. J Proteomics. 2013;85:109–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu J, Gonzalez ET, Iyer SS, Mac V, Mora AL, Sutliff RL, Reed A, Brigham KL, Kelly P, Rojas M. Use of senescence-accelerated mouse model in bleomycin-induced lung injury suggests that bone marrow-derived cells can alter the outcome of lung injury in aged mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:731–739. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu T, Ullenbruch M, Young Choi Y, Yu H, Ding L, Xaubet A, Pereda J, Feghali-Bostwick CA, Bitterman PB, Henke CA, et al. Telomerase and telomere length in pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;49:260–268. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0514OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Selman M, Pardo A. Revealing the pathogenic and aging-related mechanisms of the enigmatic idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. an integral model. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:1161–1172. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201312-2221PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hung C, Linn G, Chow YH, Kobayashi A, Mittelsteadt K, Altemeier WA, Gharib SA, Schnapp LM, Duffield JS. Role of lung pericytes and resident fibroblasts in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:820–830. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201212-2297OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rock JR, Barkauskas CE, Cronce MJ, Xue Y, Harris JR, Liang J, Noble PW, Hogan BL. Multiple stromal populations contribute to pulmonary fibrosis without evidence for epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:E1475–E1483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117988108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kage H, Borok Z. EMT and interstitial lung disease: a mysterious relationship. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2012;18:517–523. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3283566721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katsumoto TR, Violette SM, Sheppard D. Blocking TGFβ via Inhibition of the αvβ6 Integrin: A Possible Therapy for Systemic Sclerosis Interstitial Lung Disease. Int J Rheumatol. 2011;2011:208219. doi: 10.1155/2011/208219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horan GS, Wood S, Ona V, Li DJ, Lukashev ME, Weinreb PH, Simon KJ, Hahm K, Allaire NE, Rinaldi NJ, et al. Partial inhibition of integrin alpha(v)beta6 prevents pulmonary fibrosis without exacerbating inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:56–65. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200706-805OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hahm K, Lukashev ME, Luo Y, Yang WJ, Dolinski BM, Weinreb PH, Simon KJ, Chun Wang L, Leone DR, Lobb RR, et al. Alphav beta6 integrin regulates renal fibrosis and inflammation in Alport mouse. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:110–125. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howell DC, Johns RH, Lasky JA, Shan B, Scotton CJ, Laurent GJ, Chambers RC. Absence of proteinase-activated receptor-1 signaling affords protection from bleomycin-induced lung inflammation and fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1353–1365. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62354-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chambers RC, Dabbagh K, McAnulty RJ, Gray AJ, Blanc-Brude OP, Laurent GJ. Thrombin stimulates fibroblast procollagen production via proteolytic activation of protease-activated receptor 1. Biochem J. 1998;333:121–127. doi: 10.1042/bj3330121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chambers RC, Leoni P, Blanc-Brude OP, Wembridge DE, Laurent GJ. Thrombin is a potent inducer of connective tissue growth factor production via proteolytic activation of protease-activated receptor-1. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35584–35591. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003188200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blanc-Brude OP, Archer F, Leoni P, Derian C, Bolsover S, Laurent GJ, Chambers RC. Factor Xa stimulates fibroblast procollagen production, proliferation, and calcium signaling via PAR1 activation. Exp Cell Res. 2005;304:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mercer PF, Johns RH, Scotton CJ, Krupiczojc MA, Königshoff M, Howell DC, McAnulty RJ, Das A, Thorley AJ, Tetley TD, et al. Pulmonary epithelium is a prominent source of proteinase-activated receptor-1-inducible CCL2 in pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:414–425. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200712-1827OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jenkins RG, Su X, Su G, Scotton CJ, Camerer E, Laurent GJ, Davis GE, Chambers RC, Matthay MA, Sheppard D. Ligation of protease-activated receptor 1 enhances alpha(v)beta6 integrin-dependent TGF-beta activation and promotes acute lung injury. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1606–1614. doi: 10.1172/JCI27183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scotton CJ, Krupiczojc MA, Königshoff M, Mercer PF, Lee YC, Kaminski N, Morser J, Post JM, Maher TM, Nicholson AG, et al. Increased local expression of coagulation factor X contributes to the fibrotic response in human and murine lung injury. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2550–2563. doi: 10.1172/JCI33288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mercer PF, Chambers RC. Coagulation and coagulation signalling in fibrosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832:1018–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mehal WZ, Iredale J, Friedman SL. Scraping fibrosis: expressway to the core of fibrosis. Nat Med. 2011;17:552–553. doi: 10.1038/nm0511-552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noth I, Anstrom KJ, Calvert SB, de Andrade J, Flaherty KR, Glazer C, Kaner RJ, Olman MA Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Clinical Research Network (IPFnet) A placebo-controlled randomized trial of warfarin in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:88–95. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201202-0314OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Markart P, Nass R, Ruppert C, Hundack L, Wygrecka M, Korfei M, Boedeker RH, Staehler G, Kroll H, Scheuch G, et al. Safety and tolerability of inhaled heparin in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2010;23:161–172. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2009.0780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hubbard R, Venn A, Lewis S, Britton J. Lung cancer and cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis. A population-based cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:5–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.1.9906062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vancheri C. Common pathways in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and cancer. Eur Respir Rev. 2013;22:265–272. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00003613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daniels CE, Jett JR. Does interstitial lung disease predispose to lung cancer? Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2005;11:431–437. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000170521.71497.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rabinovich EI, Kapetanaki MG, Steinfeld I, Gibson KF, Pandit KV, Yu G, Yakhini Z, Kaminski N. Global methylation patterns in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e33770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cool CD, Groshong SD, Rai PR, Henson PM, Stewart JS, Brown KK. Fibroblast foci are not discrete sites of lung injury or repair: the fibroblast reticulum. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:654–658. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200602-205OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Y, Jiang D, Liang J, Meltzer EB, Gray A, Miura R, Wogensen L, Yamaguchi Y, Noble PW. Severe lung fibrosis requires an invasive fibroblast phenotype regulated by hyaluronan and CD44. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1459–1471. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Groves AM, Win T, Screaton NJ, Berovic M, Endozo R, Booth H, Kayani I, Menezes LJ, Dickson JC, Ell PJ. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and diffuse parenchymal lung disease: implications from initial experience with 18F-FDG PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:538–545. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, Azuma A, Brown KK, Costabel U, Cottin V, Flaherty KR, Hansell DM, Inoue Y, et al. INPULSIS Trial Investigators. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2071–2082. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vanhaesebroeck B, Guillermet-Guibert J, Graupera M, Bilanges B. The emerging mechanisms of isoform-specific PI3K signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:329–341. doi: 10.1038/nrm2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White ES, Atrasz RG, Hu B, Phan SH, Stambolic V, Mak TW, Hogaboam CM, Flaherty KR, Martinez FJ, Kontos CD, et al. Negative regulation of myofibroblast differentiation by PTEN (Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog Deleted on chromosome 10) Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:112–121. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200507-1058OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xia H, Diebold D, Nho R, Perlman D, Kleidon J, Kahm J, Avdulov S, Peterson M, Nerva J, Bitterman P, et al. Pathological integrin signaling enhances proliferation of primary lung fibroblasts from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1659–1672. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]