Abstract

Introduction

Cluster randomised trials (CRTs) randomise participants in groups, rather than as individuals, and are key tools used to assess interventions in health research where treatment contamination is likely or if individual randomisation is not feasible. Missing outcome data can reduce power in trials, including in CRTs, and is a potential source of bias. The current review focuses on evaluating methods used in statistical analysis and handling of missing data with respect to the primary outcome in CRTs.

Methods and analysis

We will search for CRTs published between August 2013 and July 2014 using PubMed, Web of Science and PsycINFO. We will identify relevant studies by screening titles and abstracts, and examining full-text articles based on our predefined study inclusion criteria. 86 studies will be randomly chosen to be included in our review. Two independent reviewers will collect data from each study using a standardised, prepiloted data extraction template. Our findings will be summarised and presented using descriptive statistics.

Ethics and dissemination

This methodological systematic review does not need ethical approval because there are no data used in our study that are linked to individual patient data. After completion of this systematic review, data will be immediately analysed, and findings will be disseminated through a peer-reviewed publication and conference presentation.

Keywords: Missing data, Dropout, Cluster randomized trials, Bias

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to evaluate statistical analysis and handling of missing outcome data in cluster randomised trials (CRTs).

The study uses prespecified search strategy, study selection criteria and data extraction strategy, which minimises the potential for bias during the review process.

Study selection criteria encompass a wide range of CRTs including stepped wedge designs and feasibility studies.

Pilot testing will be performed on several trials by three independent reviewers. Data collection will be carried out by two independent reviewers to ensure accuracy.

The study is subject to potential selection bias. Researchers who include terms such as ‘cluster randomised’ in the title or abstract may be more likely to follow the CONSORT statement compared with trials that do not include these terms. Researchers who do not realise their trials are CRTs are likely to use less robust methods.

Introduction

Cluster randomised trials (CRTs) randomise groups of participants to intervention arms, as opposed to individual participants. CRTs are frequently used in health research to minimise intervention arm contamination, or to assess interventions that can only be carried out at a cluster (eg, physician, centre) level.1 2

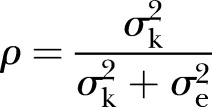

Cluster-level allocation generates several issues for statistical analysis. Participants cannot be assumed to be independent because of the similarity among participants within the same cluster. The intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) is the statistical measure of this within-cluster dependence. Suppose some variable y was measured on n individuals divided into k clusters. The ICC, ρ, is the proportion of variance due to clustering, given by:

|

where  and

and  denote the between-cluster and within-cluster variances, respectively. Ignoring clusters in the analysis can lead to falsely low p values, overly narrow CIs, and increased type I error rates.3

4

denote the between-cluster and within-cluster variances, respectively. Ignoring clusters in the analysis can lead to falsely low p values, overly narrow CIs, and increased type I error rates.3

4

Missing data lead to a reduction of power, compromise the benefits of randomisation and are a potential source of bias. In practice, there will almost always be some missing data.5 6 Recent reviews in individual randomised trials have found that the majority have missing outcome data.7–10 Missing data mechanisms have been broadly categorised into the following three classes. Data are said to be missing completely at random (MCAR) if the reason for a missing observation is unrelated to observed values of the outcome and covariates. MCAR is a strong assumption and unlikely in most trials. A more reasonable assumption is missing at random (MAR), where missingness does not depend on the unobserved data, conditional on the observed data. Lastly, data are considered missing not at random if missingness depends on the unseen value of that observation even after conditioning on fully observed data.6 11

Several reviews have been published regarding CRTs.12–22 Most have reported inadequate accounting for clustering in sample size and analysis. One review of CRTs published in 2011 focused on imputation techniques with respect to handling missing data and did not discern between missing covariates or outcomes.23 Modelling approaches can differ based on whether outcomes or covariates are missing: if covariates are missing, multiple imputation (MI) or an unadjusted model can be used. If outcomes are missing, maximum likelihood estimation using mixed models, for example, can provide unbiased estimation in certain cases (see below). Additionally, there was no distinction of whether trials used a complete case analysis, generalised estimating equations (GEE) or mixed models with respect to handling missing data in the primary analysis. Distinguishing between these methods is important, as they may provide valid estimates under certain missing data assumptions. Our objective is to provide a comprehensive review of analytical approaches for handling missing outcome data in CRTs. The primary aims of our review are to evaluate approaches used to analyse primary outcome data in CRTs and investigate methods used to handle missing outcome data in primary and sensitivity analysis. As a secondary aim, we will evaluate methods for achieving balance in CRTs by examining the proportions of CRTs that use stratification, matching or minimisation.

Methods

Our systematic review will investigate statistical analyses and missing data strategies used in CRTs. This section contains an introduction of commonly used statistical approaches and missing data methods used for analysing clustered data, followed by a detailed description of our methodological strategy based on guidelines from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement.24

Statistical approaches for analysing CRTs

Two standard approaches to analyse CRTs include analysis at the cluster level and analysis at the individual level. Cluster-level analysis involves reducing all observations within a cluster to a single summary measure, such as a cluster mean or proportion. Standard statistical tests (eg, t tests, linear regression models) can then be performed since each data point can now be considered independent.4 25 Even though cluster-level analysis solves the problem of dependent data, reducing observations to single summary statistics leads to a reduction in sample size and as a result, statistical power. Modelling techniques incorporating individual-level covariates in cluster-level analysis, such as generalised linear mixed models (GLMM) and GEE, have also been developed.26 27 GEE and GLMM explicitly involve intracluster correlation in the modelling process, which enables a more realistic model of the clustered data. An advantage of these types of models is the ability to control for confounding at the individual level and reduce bias. However, drawbacks of this approach are that they are more computationally intensive and require a higher sample size of relatively large clusters.25 28

Missing data methods in CRTs

Common approaches for handling missing outcome data include complete case analysis, single imputation, MI and model-based analysis. Complete case analysis excludes participants with missing data and is valid (produces unbiased estimates) if missingness is independent of the outcome, given covariates.29 Single imputation strategies fill-in missing data with a single value, thereby underestimating uncertainty. Under the MAR assumption, MI takes into account uncertainty by replacing each missing value with a set of possible values to create multiple imputed data sets. However, most implementations are single level, ignoring the hierarchical data structure of CRTs. Multilevel MI reflects the lack of independence found within clusters due to the multilevel structure of CRTs.30 31 Model-based methods include linear mixed models, valid for MAR data, if the model is specified correctly, and GEE, which is valid under the stronger MCAR assumption as long as there are a large number of clusters.28 32 Inverse probability weighting (IPW) is used to make a valid complete case analysis under MAR by weighting complete cases with the inverse of their probability of having data observed.33 The IPW approach is relatively simple to carry out when missing values have a monotone pattern and can be applied to GEE. However, there is possible instability when weights are extremely large, which can lead to biased estimates and high variance in small samples.6

Search strategy

CRTs published in English between August 2013 and July 2014 will be sought. Two authors (MF and SH) will systematically search for CRTs indexed in the following electronic bibliographic databases: PubMed, Web of Science (all databases) and PsycINFO. The search strategy will include the terms “cluster randomized [randomised]”, “cluster and trial”, “community trial”, “community randomized [randomised]” or “group randomized [randomised]” found in titles and abstracts. An example of our search strategy including search terms is found in online supplementary file 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We will include all CRT designs, including stepped wedge trials.34 We will exclude protocols of trials, observational studies, secondary reports of trials, studies in which no data were collected at the individual level and quasi-experimental cluster designs. Trials with survival outcomes will also be excluded, as missing time-to-event data are handled quite differently to other types of outcome data.

Study selection

Two independent reviewers (MF and SH) will identify eligible studies using the search strategy. All studies will be imported using EndNote (EndNote X6, Thomson Reuters, New York, USA). The reviewers will remove duplicates and go through titles and abstracts to identify eligible studies. Full-text articles will be retrieved if the reviewer identified the article to answer ‘yes’ or ‘unclear’ to all selection criteria. The reviewers will collect and evaluate the full text article, and identify relevant studies based on study inclusion criteria. Reviewers will keep track of the number of studies excluded from each screening step.

Sample size

We hypothesise 90% of trials having some missing outcome data. We estimate that a sample size of 86 papers will result in a margin of error of 6 percentage points (95% CI 84 to 96).

Data extraction strategy

Pilot testing of coding will be carried out with both reviewers (MF and SH) and the senior author (MLB). All piloted papers will be included in the review. Two independent reviewers (MF and SH) will collect data from each study using a standardised, prepiloted data extraction template. Disagreements over the eligibility or data extraction of particular studies will be handled by consensus or a third reviewer where consensus was not achieved.

Extracted information will include: general information (journal, author, date of publication, pilot/feasibility study or stepped wedge); characteristics of the primary outcome (type of outcome, how often outcome was collected, how outcome was treated in the primary analysis); characteristics of study participants (unit or randomisation, stratification/matching/minimisation used, number of clusters randomised, total number of participants randomised, response rate at time period of primary analysis, if survey data); details of sample size calculation (accounted for clustering in calculation, reported ICC or coefficient of variation (CV), accounted for missing outcome data in calculation, reported attrition rate in sample size calculation); primary analysis (statistical method used in primary analysis, adjustment (unadjusted, adjusted for design variables such as stratification, adjusted beyond stratification variables), clustering accounted for in analysis, observed ICC or CV, GEE correction type); information on missing data (number (and proportion) of clusters with missing outcome, number (and proportion) of participants with missing outcome, reasons for missing data, method to handle missing data in primary analysis and sensitivity analysis). If any of the items were unclear, including the amount of missing data and method used to handle missing data, we specified it as ‘unclear’. Specific details on data items, including relevant coding used during the data extraction process and definitions, are given in online supplementary file 2.

Method of analysis

Our analysis strategy follows closely after reviews by Wood et al7 and Bell et al,10 which both assessed missing outcomes in individually randomised trials. We will present a synthesis of the findings by first describing characteristics of the primary outcome and study participants of the included studies. We will then calculate the proportion of trials reporting some missing data at the individual and cluster level. This will be determined from flow diagrams or text with respect to follow-up of clusters and individuals. Of those who reported some missing data, we will calculate the proportion of trials that carried out complete case analysis, single imputation, MI, GEE or a mixed model to handle missing data in the primary analysis. Similar computations for trials that report sensitivity analysis for missing data will also be performed. We will quantify the number of trials that weakened the missingness assumption of their primary analysis to perform their sensitivity analysis as suggested by the Panel on Handling Missing Data in Clinical Trials, recently commissioned by the National Research Council.6

To evaluate prevention and planning, we will record whether sample size calculations were reported and if trials accounted for clustering and missing data. We will describe the details of analysis of primary outcomes and compare observed versus expected attrition rates and ICCs (or CVs). Quality of trials will not be assessed.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to evaluate statistical analysis and handling of missing outcome data in CRTs. We have a prespecified search strategy, study selection criteria and data extraction strategy. Systematic reviews are complicated and require judgements that should not rely on conclusions of the studies included in the review.35 By predefining our methodology, we are minimising the potential for bias during the review process. Additionally, our study selection criteria encompass a wide range of CRTs including stepped wedge designs and feasibility studies. Pilot testing will be performed on several trials by three independent reviewers. Data collection will be carried out by two independent reviewers to ensure accuracy.

A limitation of this systematic review is the difficulty in identifying CRTs since many do not use the term ‘cluster’ in the title or abstract. In an effort to alleviate this issue, we will use other commonly used terms for cluster randomisation including ‘community randomised’ or ‘group randomised’. This allows us to reach a wider range of trials that may have been missed otherwise.

Furthermore, our systematic review is subject to potential selection bias. Researchers who include terms such as ‘cluster randomised’ in the title or abstract may be more likely to follow the CONSORT statement compared with trials that do not include these terms.36 Researchers who do not realise their trials are CRTs are likely to use less robust methods.

Language bias may be introduced since we have limited our search to CRTs published in the English language.

Including studies with survival outcomes may influence missing data rates since participants are censored at dropout. We did not consider CRTs of which the primary outcome was survival because different statistical issues arise in comparison to trials with non-survival outcomes.

This review will allow us to examine current statistical methods used in practice with respect to missing outcomes in CRTs. Based on our results, we will be able to make recommendations for areas where reporting and conduct may need improvement.

Footnotes

Contributors: MF and MLB conceptualised the study. MF drafted the manuscript and incorporated comments from authors for successive drafts. SH and MLB contributed to design and content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: After completion of this systematic review, data will be immediately analysed and findings will be disseminated through a peer-reviewed publication and conference presentations.

References

- 1.Donner A, Klar N. Design and analysis of cluster randomization trials in health research. London Arnold Publishers, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell MK, Grimshaw JM. Cluster randomised trials: time for improvement. The implications of adopting a cluster design are still largely being ignored. BMJ 1998;317:1171–2. 10.1136/bmj.317.7167.1171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cornfield J. Randomization by group: a formal analysis. Am J Epidemiol 1978;108:100–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell MK, Mollison J, Steen N et al. . Analysis of cluster randomized trials in primary care: a practical approach. Fam Pract 2000;17:192–6. 10.1093/fampra/17.2.192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell ML, Fairclough DL. Practical and statistical issues in missing data for longitudinal patient-reported outcomes. Stat Methods Med Res 2014;23:440–59. 10.1177/0962280213476378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Research Council. The prevention and treatment of missing data in clinical trials. In: Committee on National Statistics, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington DC: National Academies Press, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood AM, White IR, Thompson SG. Are missing outcome data adequately handled? A review of published randomized controlled trials in major medical journals. Clin Trials 2004;1:368–76. 10.1191/1740774504cn032oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gravel J, Opatrny L, Shapiro S. The intention-to-treat approach in randomized controlled trials: are authors saying what they do and doing what they say? Clin Trials 2007;4:350–6. 10.1177/1740774507081223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fielding S, Maclennan G, Cook JA et al. . A review of RCTs in four medical journals to assess the use of imputation to overcome missing data in quality of life outcomes. Trials 2008;9:51 10.1186/1745-6215-9-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell ML, Fiero M, Horton NJ et al. . Handling missing data in RCTs; a review of the top medical journals. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:118 10.1186/1471-2288-14-118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubin DB. Inference and missing data. Biometrika 1976;63:581–92. 10.1093/biomet/63.3.581 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donner A, Brown KS, Brasher P. A methodological review of non-therapeutic intervention trials employing cluster randomization, 1979–1989. Int J Epidemiol 1990;19:795–800. 10.1093/ije/19.4.795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simpson JM, Klar N, Donnor A. Accounting for cluster randomization: a review of primary prevention trials, 1990 through 1993. Am J Public Health 1995;85:1378–83. 10.2105/AJPH.85.10.1378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith PJ, Moffatt ME, Gelskey SC et al. . Are community health interventions evaluated appropriately? A review of six journals. J Clin Epidemiol 1997;50:137–46. 10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00338-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chuang JH, Hripcsak G, Jenders RA. Considering clustering: a methodological review of clinical decision support system studies. Proc AMIA Symp 2000:146–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayes RJ, Alexander ND, Bennett S et al. . Design and analysis issues in cluster-randomized trials of interventions against infectious diseases. Stat Methods Med Res 2000;9:95–116. 10.1191/096228000670953670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Isaakidis P, Ioannidis JP. Evaluation of cluster randomized controlled trials in sub-Saharan Africa. Am J Epidemiol 2003;158:921–6. 10.1093/aje/kwg232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Puffer S, Torgerson D, Watson J. Evidence for risk of bias in cluster randomised trials: review of recent trials published in three general medical journals. BMJ 2003;327:785–9. 10.1136/bmj.327.7418.785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bland JM. Cluster randomised trials in the medical literature: two bibliometric surveys. BMC Med Res Methodol 2004;4:21 10.1186/1471-2288-4-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eldridge S, Ashby D, Bennett C et al. . Internal and external validity of cluster randomised trials: systematic review of recent trials. BMJ 2008;336:876–80. 10.1136/bmj.39517.495764.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eldridge SM, Ashby D, Feder GS et al. . Lessons for cluster randomized trials in the twenty-first century: a systematic review of trials in primary care. Clin Trials 2004;1:80–90. 10.1191/1740774504cn006rr [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varnell SP, Murray DM, Janega JB et al. . Design and analysis of group-randomized trials: a review of recent practices. Am J Public Health 2004;94:393–9. 10.2105/AJPH.94.3.393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diaz-Ordaz K, Kenward MG, Cohen A et al. . Are missing data adequately handled in cluster randomised trials? A systematic review and guidelines. Clin Trials 2014;11:590–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wears RL. Advanced statistics: statistical methods for analyzing cluster and cluster-randomized data. Acad Emerg Med 2002;9:330–41. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb01332.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics 1986;42:121–30. 10.2307/2531248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. John Wiley & Sons, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell MJ, Donner A, Klar N. Developments in cluster randomized trials and Statistics in Medicine. Stat Med 2007;26:2–19. 10.1002/sim.2731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.White IR, Carlin JB. Bias and efficiency of multiple imputation compared with complete-case analysis for missing covariate values. Stat Med 2010;29:2920–31. 10.1002/sim.3944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Buuren S. Multiple imputation of multilevel data. In: Hox JJ, Roberts JK, eds.Handbook of advanced multilevel analysis . Psychology Press, 2011:173–96. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caille A, Leyrat C, Giraudeau B. A comparison of imputation strategies in cluster randomized trials with missing binary outcomes. Stat Methods Med Res 2014. Published Online First 7 Apr 2014. doi:10.1177/0962280214530030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robins J, Rotnitzky A, Zhao LP. Analysis of semiparametric regression models for repeated outcomes in the presence of missing data. J Am Stat Assoc 1995;90:106–21. 10.1080/01621459.1995.10476493 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robins JM, Rotnitzky A, Zhao LP. Estimation of regression coefficients when some regressors are not always observed. J Am Stat Assoc 1994;89:846–66. 10.1080/01621459.1994.10476818 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hussey MA, Hughes JP. Design and analysis of stepped wedge cluster randomized trials. Contemp Clin Trials 2007;28:182–91. 10.1016/j.cct.2006.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Wiley Online Library, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell MK, Elbourne DR, Altman DG et al. . CONSORT statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 2004;328:702–8. 10.1136/bmj.328.7441.702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]