Abstract

Objectives

Computerised clinical decision support systems (CCDSS) are used to improve the quality of care in various healthcare settings. This systematic review evaluated the impact of CCDSS on improving medication safety in long-term care homes (LTC). Medication safety in older populations is an important health concern as inappropriate medication use can elevate the risk of potentially severe outcomes (ie, adverse drug reactions, ADR). With an increasing ageing population, greater use of LTC by the growing ageing population and increasing number of medication-related health issues in LTC, strategies to improve medication safety are essential.

Methods

Databases searched included MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus and Cochrane Library. Three groups of keywords were combined: those relating to LTC, medication safety and CCDSS. One reviewer undertook screening and quality assessment.

Results

Overall findings suggest that CCDSS in LTC improved the quality of prescribing decisions (ie, appropriate medication orders), detected ADR, triggered warning messages (ie, related to central nervous system side effects, drug-associated constipation, renal insufficiency) and reduced injury risk among older adults.

Conclusions

CCDSS have received little attention in LTC, as attested by the limited published literature. With an increasing ageing population, greater use of LTC by the ageing population and increased workload for health professionals, merely relying on physicians’ judgement on medication safety would not be sufficient. CCDSS to improve medication safety and enhance the quality of prescribing decisions are essential. Analysis of review findings indicates that CCDSS are beneficial, effective and have potential to improve medication safety in LTC; however, the use of CCDSS in LTC is scarce. Careful assessment on the impact of CCDSS on medication safety and further modifications to existing CCDSS are recommended for wider acceptance. Due to scant evidence in the current literature, further research on implementation and effectiveness of CCDSS is required.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first systematic review to explore the role of computerised clinical decision support systems (CCDSS) in improving medication safety in long-term care homes.

A quality assessment was carried out with the Downs and Black tool for each study included in the review.

A limitation of this study is that there was just one reviewer.

Another limitation is that the search was limited to the English language.

Introduction

In countries such as the USA, about 1.5 million patients are harmed each year, and over 140 000 people die from medication errors.1 Adverse drug events (ADE) cost $3.5 billion annually in the USA, not counting lost productivity or additional healthcare costs.2 Gurwitz et al3 found that approximately 95% of adverse drug reactions (ADR) are predictable, and approximately 28% are preventable. In the UK, there are as many as 250 000 adverse reactions to medicines at a cost of £466 million to the National Health Services (NHS) annually.1 Studies in Australia,4 New Zealand,5 Denmark6 and Thailand,7 reveal similar levels of harm from unsafe medication, confirming that medication safety is a global priority.

Medication safety includes, but is not restricted to, preventing adverse reactions, medication errors, adverse events and other medication-related problems. It also includes ensuring safety during prescribing, administering and monitoring of drugs.8 Medication safety can be compromised during prescribing and administrating due to wrong dose, drug or route; incorrect data entry; inadequate communication; lack of consideration of patient factors such as allergies, comorbidities and multiple medications; and illegible, incomplete or ambiguous documentation. Medication safety can also be compromised during monitoring due to inattention to side effects, ceasing drugs before completing course, failure to cease drugs if not working or course is incomplete, poor measurements of drugs and failure to follow-up.8

In long-term care homes (LTC), almost all residents receive one or more prescribed medications. A Canadian study found that LTC in metropolitan Quebec had 94% of their residents receiving >1 prescribed medication and about 5 prescribed medications on average, with a majority of treated patients (54.7%) having a potentially inappropriate prescription (PIP).9 Furthermore, globally, a Malaysian nursing home reported that 33% of its residents had experienced PIPs.10 Ruggiero et al11 revealed that about 48% of nursing home residents at an Italian nursing home had at least one PIP, with 18% residents having two or more PIPs. Furthermore, 30% of hospital admissions in elderly patients are linked to ADE caused by a medication.12

The most common cause of ADE is inappropriate medication prescribing.12 Inappropriate prescribing is higher among the elderly in LTC compared with community dwelling elderly, with estimates as high as 33–40%.12–15 Older adults residing in LTC have multiple medical conditions, multiple drug regimens, and functional and cognitive impairment, which contribute to a higher risk of ADR. Therefore, interventions to avoid medication-related problems to improve medication safety in LTC are imperative.

Computerised clinical decision support systems (CCDSS)i 16 17 are not the only solution to improving medication safety, but they are considered to be among the more promising solutions. CCDSS improve medication safety by providing recommendations relating to dosing,18–20 administration frequencies,19 medication discontinuation,20 and medication avoidance;19 and alerts on drug duplication, contraindications, drug interaction errors,21 appropriate medication orders19 and warning messages,22 to improve the quality of prescribing decisions. CCDSS can be applied during the prescribing, administering or monitoring stages to detect and prevent faults related to medication.

The number of older adults expected to live in institutions is projected to almost double over the next three decades,23 increasing frailty and care needs that exceed the capacity of healthcare providers. Therefore, the use of CCDSS is essential to make decision-making processes easier, to detect errors that humans cannot always distinguish and to ease the workload for healthcare providers.

This systematic review investigates the current use, benefits and effectiveness of CCDSS in LTC to improve medication safety. The aim of this research is to contribute to ensuring medication safety for older adults residing in LTC; reducing the added burden on the healthcare system from medication-related issues (ie, rehospitalisations); improving healthcare system efficiency; and enhancing overall quality of care in LTC.

Methods

Data sources and search strategy

The search strategy aimed to retrieve papers that focused on CCDSS to improve medication safety in LTC (nursing homes, personal care facilities, residential continuing care facilities; defined in Health Care System, available on the Health Canada website).24 Databases searched included MEDLINE (1950 to 1st week of February 2014), EMBASE (1980 to 1st week of February 2014), Scopus (1966 to 1st week of February 2014) and Cochrane Library (1996 to 1st week of February 2014).

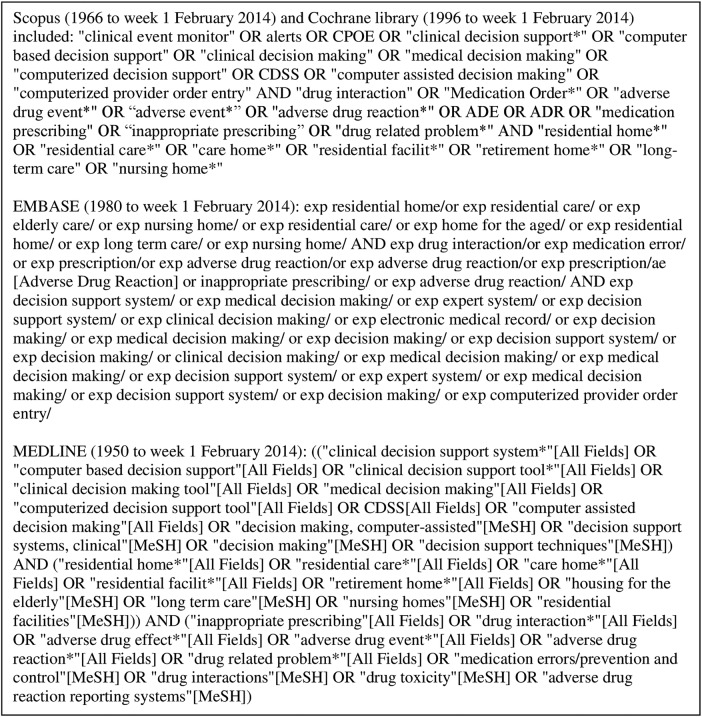

Three groups of keywords were combined: those relating to long-term care, medication safety and CCDSS as listed in figure 1. Retrieved articles were initially reviewed by the title and abstract to find potentially relevant papers. Relevant articles by title and abstract were reviewed to obtain articles that met the inclusion criteria. Reference lists of all relevant articles by title and abstract were reviewed to identify any further relevant papers.

Figure 1.

Search terms used in each database.

Study selection-inclusion criteria

Selected papers were assessed against the following inclusion criteria: (1) they were randomised controlled trials (RCT), cohort studies, retrospective and prospective studies; (2) they had long-term care-based settings; (3) they evaluated the effect of CCDSS aimed at improving medication safety and (4) they were written in English.

Exclusion criteria

If the abstract indicated that the study did not relate to CCDSS intervention to improve medication safety in LTC, the study was excluded. All commentaries were excluded.

Data extraction, analysis and quality assessment

One reviewer performed the search, and screened titles and abstracts to identify the studies that met the inclusion criteria. Relevant full articles were reviewed to extract details about the study population (ie, mean age), sample size, intervention (ie, description, methods and study period), outcome measurements and significant outcomes (table 1). Outcome measurements such as the number of ADE, severity and preventability of the events; amount of signals that detected ADR; amount of preventable ADR and serious ADR; proportion of alerts that were followed by an appropriate action; proportion of appropriate final drug orders; overall rates of inappropriate orders; percentage of medication orders that were modified in response to alerts; and injury risk at the end of follow-up within in each study, were evaluated to understand the overall outcome of each study (table 1). Relative risks (RR), positive predictive values and rate ratios, as reported by each study, were evaluated to assess the influence of CCDSS in improving medication safety in LTC (table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the results

| Author, year | Study population | Sample size | Intervention | Outcome | Significant outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donovan et al 201018 | LTC residents Mean age=85.8 |

n=813 | Randomised trial conducted at a long-term care facility equipped with an integrated EMR and CPOE over a 1-year period. Randomisation was within blocks according to resident unit type. CDSS for 22 psychotropic medications was developed. CDSS had 2 broad alert categories; ‘dosing’ and ‘avoid’ to identify inappropriate psychotropic medication orders | The overall rates of inappropriate orders Percentages of medication orders that were modified in response to alerts |

CDSS provided to prescribers influenced prescribing decision, although no overall improvement in prescribing quality was noted. |

| Field et al 200919 | LTC residents Mean age=86.3 |

n=833 | Randomised trial within the long-stay units of a long-term care facility. Alerts related to medication prescribing for residents with renal insufficiency were displayed to prescribers in the intervention units and hidden but tracked in control units. 4 types of alerts were developed: (1) recommended medication doses, (2) recommended administration frequencies, (3) to avoid the drug and (4) warnings of missing information. Alerts were measured over 1-year period | Proportion of final drug orders that were appropriate | CCDSS for physicians prescribing medications for LTC residents with renal insufficiency improved the quality of prescribing decisions. Higher proportions of final drug orders were appropriate in the intervention units (RR=2.4, 1.4 to 4.4 for maximum frequency; RR=2.6, 1.4 to 5.0 for drugs that should be avoided; and RR=1.8, 1.1 to 3.4 for alerts to acquire missing information). Final drug orders were appropriate significantly more often in the intervention units (alerts displayed) with a RR of 1.2 (1.0 to 1.4). |

| Gurwitz et al 200828 | LTC residents Mean age=87.2 | n=1118 | 29 resident care units were randomised to having a CCDSS or not. In the intervention unit, prescribers were presented with alerts while alerts were not displayed to prescribers in the control units over a 1-year period | Number of ADE, severity and preventability of the events | CPOE with DSS did not reduce ADE rate or preventable drug event rate in the LTC. |

| Handler et al 200827 | All nursing home residents except those enrolled in hospice | n=274 | A clinical event monitor (a type of CCDSS) implemented and evaluated in the detection of ADR in a nursing home over 15-week period | PPV of signals that detected ADR, the amount of preventable ADR and serious ADR | ADR can be detected in the nursing homes with a high degree of accuracy using a clinical event monitor. The overall PPV for all signals was 81%. Of the true positive findings, one-third of the ADR were considered preventable. Of the preventable ADR, 88% occurred at the monitoring and 69% at the prescribing stage. |

| Judge et al 200622 | Residents in the long-stay units of the LTC | n=445 | RCT of CCDSS in the long-stay units of a long-term care facility. CCDSS was added to an existing CPOE system. Over 1-year, prescribers in the intervention units were presented with alerts and prescribers in the control units were not displayed alerts. CCDSS was designed to provide alerts on: (1) drug interactions, (2) danger related to the ordered medication, (3) risk of adverse effects, (4) dose ranges and (5) likelihood of adverse drug effects | The proportion of alerts that were followed by an appropriate action | Of 47 997 medication orders, 9414 alerts were triggered (2.5 alerts per resident per month); 20% central nervous system-related side effect alerts such as oversedation, 13% drug-associated constipation alerts, 12% renal insufficiency/electrolyte imbalance alerts and 12% warfarin-related alerts. CCDSS with CPOE is effective in presenting alerts, therefore represents as a tool to improve medication safety. Prescribers who received alerts were only slightly more likely to take an appropriate action (RR=1.11, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.22). |

| Kennedy et al 201120 | Residents in LTC with renal impairment. Mean age=87.0±7.4 |

n=1196 | A CCDSS developed in partnership with a large pharmacy provider that generated renal prescribing alerts. 7 LTC across Ontario, Canada participated in a 3-month programme evaluation | The number of alerts and the physician response to alerts | Physicians responded to 70% of the alerts with a dose change or medication discontinuation. During the 3 months’ duration, 446 alerts were generated in 321 residents; 27% of all residents received at least 1 alert. |

| Tamblyn et al 201221 | Patients aged 65 and older who were prescribed psychotropic medication Mean age=75.2 |

n=5628 | Cluster RCT intervention tested whether CDSS with patient-specific risk estimates would increase physician response to alerts and reduce the risk of injury in older adults over a 2-year period. Physicians in the intervention unit received a patient-specific risk of injury alert when a patient was prescribed a psychotropic medication that increased the risk of injury while physicians in the control unit received commercial drug alerts. In a secondary analysis, physicians’ response to the injury risk alert and changes in the use and dose of psychotropic medications were assessed | Injury risk at the end of follow-up based on psychotropic drug doses and non-modifiable risk factors | CCDSS with patient-specific risk estimates provide an effective method to reduce the risk of injury for vulnerable older adults. The intervention reduced the risk of injury by 1.7 injuries/1000 patients (95% CI 0.2/1000 to 3.2/1000; p=0.02). The effect of the intervention was greater for patients with higher baseline risks of injury (p<0.03). Intervention physicians reviewed therapy in 83.3% of visits and modified therapy in 24.6% visits. |

ADE, adverse drug events; ADR, adverse drug reactions; CCDSS, computerised clinical decision support system; CDSS, clinical decision support system; CPOE, computerised physician order entry; DSS, decision support system; EMR, electronic medical records; PPV, positive predictive value; RCT, randomised controlled trials; RR, relative risk; LTC, long-term care home.

A quality assessment was carried out using the Downs and Black tool (See online supplementary table S1).25 This quality assessment scale (QAS) assesses study reporting, external validity and internal validity, and has been ranked in the top six QAS suitable for use in systematic reviews.26 The tool was slightly modified for use in this review. The scoring for question 27 dealing with statistical power was simplified to a choice of awarding either 1 or 0 points, depending on whether there was sufficient power to detect a clinically significant effect. The maximum score for question 5 was changed from a maximum score of 2 to a score of either 1 or 0. Owing to the non-relevancy of question 16, it was excluded. Therefore, the maximum score used in this review was 26. Each question received a score of 1 if the answer was ‘yes’, or 0 if the answer was ‘no’ or ‘unable to determine’. A higher score reflected better study quality.

Downs and Black score ranges were grouped into the following three quality levels: good (≥20), fair (15–19) and poor (≤14).

Results

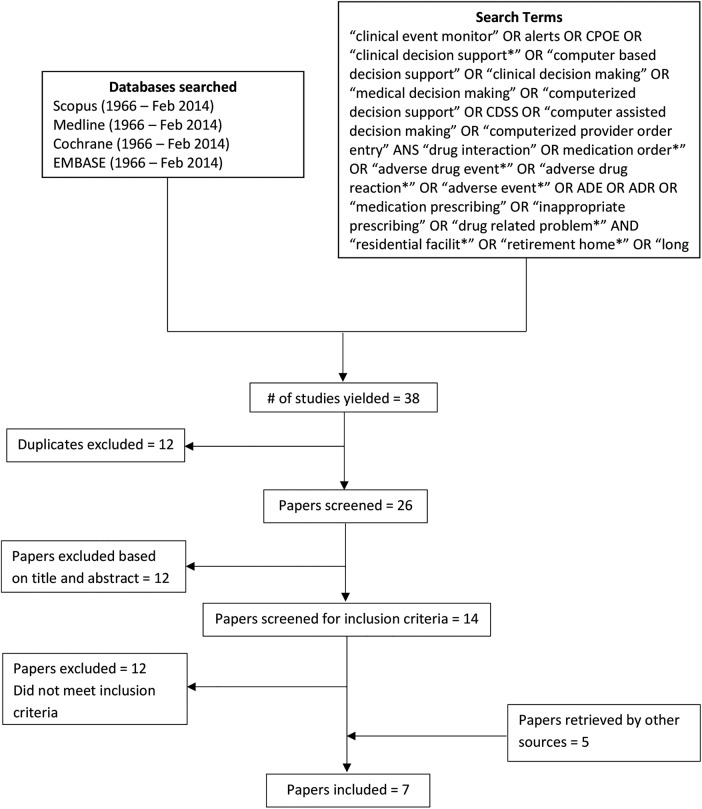

A total of 38 possible relevant records were identified. After excluding duplicates, 26 records were screened to yield 14 articles eligible for full-text screening. Of those, two articles met the inclusion criteria19 27 and five relevant articles were retrieved through other sources,18 20–22 28 totalling seven final articles (figure 2). Out of the seven articles, five studies were RCT. All seven articles18–22 27 28 reviewed the impact of CCDSS in improving medications safety in LTC, and represented older populations (mean age varying from 75–87; table 1).

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of literature search.

The quality of the studies was generally good and fair ranging from scores 14 to 21 (median 19, average 19). Out of the seven studies examined, three studies were of good quality, scoring 21–22, three studies were of fair quality, scoring 16–19, and one study was of poor quality, scoring 14 on the modified Downs and Black scale (See online supplementary table S1).

Discussion

The systematic review found that investigation of CCDSS in improving medication safety among older adults in LTC has received little attention as attested by the limited published literature. Five studies showed positive findings on improving medication safety in LTC.19–22 27 Two studies found no improvement in overall medication safety.18 28 Out of the five positive studies, one study showed positive findings in regard to the amount of warnings messages triggered; however, it showed negative findings towards prescribers’ response to alerts.22 This study is considered as a positive finding in this review because triggering of warning messages (ie, related to central nervous system side effects, drug associated constipation, renal insufficiency to name a few) contributed to overall medication safety. While prescribers’ response to the alerts also contribute to overall medication safety, their response may depend on multiple other factors (ie, personal choice, prescribers’ acceptance/confidence in CCDSS, etc), which can be separately explored with further research.

Studies focused on improving medication safety with CCDSS through providing recommendations for medication doses, administration frequencies, avoidance of medication and warnings of missing information;19 detecting ADR;27 triggering warning messages;22 presenting alerts for dose change or medications discontinuation;20 and reducing risk of injury from medication side effects.21 Through recommended medication doses, administration frequencies, avoidance of the medication and warnings of missing information, proportions of appropriate final drug orders were improved. In addition, studies show that CCDSS were able to provide alerts and the appropriate drug orders for a vast number of medications (ie, approximately 35 medications), and detect potential ADR for multiple medication categories (ie, antidote signals, laboratory/medication signals), demonstrating the ability to provide recommendations for multiple drug orders simultaneously and detect comprehensive potential ADR in a short period of time, for which mere human capacity will not suffice. Furthermore, CCDSS with patient-specific risk estimates provided an effective method to reduce the risk of injury for vulnerable older adults. The effect of the intervention was greater for individuals with higher baseline risk injury (ie, fall-related injury), which demonstrates the suitability of CCDSS for LTC where most vulnerable older adults reside.

In addition to above means of improving medications safety, four studies looked at prescribers’ response to the alerts provided. Two of the four studies produced a greater response to alerts than previous studies did.20 21 Drug modification, dose changes and medication discontinuation were among the actions taken in response to alerts, showing the CCDSS’ ability to improve prescribing decisions. Two studies had relatively low response rates, although no overall improvement in prescribing quality was noted.18 28 Low response to alerts can be explained by physicians’ tendency to ignore alerts that are too frequent or consider them irrelevant, which affects their confidence in CCDSS. Lack of confidence in CCDSS demands careful assessment on the impact of CCDSS on medication safety; excessive numbers of alerts and high signal to noise ratios causing alert burden calls for further modifications to the systems; and lack of suggested actions within alerts that prescribers could directly accept (ie, an alternative order) requires further improvements to the existing CCDSS.

The quality of the studies was fair on average, therefore results should be interpreted with caution. Despite the limitations within CCDSS in some studies, overall findings suggest that CCDSS in LTC improved the quality of prescribing decisions (ie, appropriate medications orders),19 detected ADR,27 triggered warning messages (ie, related to central nervous system side effects, drug-associated constipation, renal insufficiency) and reduced injury risk among older adults.21 These means of improving medication safety ensure safety for older adults, as well as reduce the added burden on the healthcare system (ie, preventable falls, fractures, rehospitalisations, added cost, to name a few). Avoiding medication-related problems improves healthcare system efficiency, as also described by Berner,29 Garg et al,30 Hemens et al16 and Teich et al,31 and enhances overall quality of care in LTC; therefore it is worthwhile to investigate the benefits and effectiveness of CCDSS to improve medication safety within the healthcare system.

Limitations

The review retrieved a limited number of publications. This can be partly explained by the noticeable lack of research in the field of CCDSS to improve medication safety, especially in LTC, which strongly emphasises the need for further research. Publication bias is possibly another explanation for the limited number of publications; however, the review included positive as well as negative findings. Another limitation is that the search was limited to the English language. It is possible to have promising research published in different languages that the cumulative evidence of this review would not have included. One reviewer conducting the review may also be a limitation; having multiple reviewers would be an advantage to the study. Despite the limitations, the author believes that the findings are important and emphasise an approach to improve medication safety for older adults.

Conclusion and recommendations

CCDSS have received little attention in LTC, as attested by the limited published literature. With an increasing ageing population, high number of expected LTC residents over the next three decades,23 and increased frailty and care needs that exceed the capacity of healthcare providers, merely relying on physicians’ judgement on medication safety would not be sufficient. Therefore, further initiatives such as the use of CCDSS to make decision-making processes easier, to detect medications errors that humans cannot always distinguish and to ease the workload for healthcare providers, is imperative.

Analysis of review findings indicates that CCDSS are beneficial, effective and have great potential to improve medication safety in LTC; however, CCDSS use in LTC is limited. Careful assessment on the impact of CCDSS on medication safety and further modifications to the existing CCDSS are recommended for wider acceptance. Owing to scant evidence in the current literature, further research on CCDSS implementation and effectiveness is required.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

CCDSS algorithmically apply an electronic knowledge base to individual patient data to generate and present suggested actions. CCDSS for medication safety are used to facilitate evidence-informed medication use and to reduce the incidence of harmful medication errors among other uses. This review considered any CCDSS that offer recommendations to healthcare providers regarding the initiation, administration, modification, monitoring or discontinuation of medication based on the patient’s characteristics (ie, clinical event monitor).

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Engaging patients in medication safety. 66th World Health Assembly, 2013.

- 2.Institute of Medicine Committee on Identifying and Preventing Medical Errors. Preventing medical errors. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2006:132. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Harrold LR et al. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events among older persons in the ambulatory setting. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2003;289:1107–16. 10.1001/jama.289.9.1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson RM, Runciman WB, Gibberd RW et al. The quality in Australian health care study. Med J Aust 1995;63:458–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis PB, Lay-Yee R, Briant RH et al. Adverse events in New Zealand public hospitals: principal findings from a national survey. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Health, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schiøler T, Lipczak H, Pedersen BL et al. Incidence of adverse events in hospitals. A retrospective study of medical records. Ugeskr Laeger 2001;163:5370–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anansakunwatt W, Kessomboon P. A WHO sponsored study in progress 2013.

- 8.World Health Organization. Topic 11: Improving medication safety. Secondary Topic 11: Improving medication safety 2014. http://www.who.int/patientsafety/activities/technical/who_mc_topic-11.ppt

- 9.Rancourt C, Moisan J, Baillargeon L et al. Potentially inappropriate prescriptions for older patients in long-term care. BMC Geriatr 2004;4:9 10.1186/1471-2318-4-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen LL, Tangiisuran B, Shafie AA et al. Evaluation of potentially inappropriate medications among older residents of Malaysian nursing homes. Int J Clin Pharm 2012;34:596–603. 10.1007/s11096-012-9651-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruggiero C, Dell'Aquila G, Gasperini B et al. Potentially inappropriate drug prescriptions and risk of hospitalization among older, Italian, nursing home residents: the ULISSE project. Drugs Aging 2010;1:747–58. 10.2165/11538240-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roehl B, Talati A, Parks S. Medication prescribing for older adults. Ann Longterm Care 2006;14:33–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhall J, Larrat EP, Lapane K. Use of potentially inappropriate drugs in nursing homes. Pharmacotherapy 2002;22:88–96. 10.1592/phco.22.1.88.33503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piecoro LT, Browning SR, Prince TS et al. A database analysis of potentially inappropriate drug use in an elderly Medicaid population. Pharmacotherapy 2000;20:221–8. 10.1592/phco.20.3.221.34779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beers MH, Ouslander JG, Fingold SF et al. Inappropriate medication prescribing in skilled nursing facilities. Ann Intern Med 1992;117:684–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-117-8-684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hemens BJ, Holbrook A, Tonkin M et al. Computerized clinical decision support systems for drug prescribing and management: a decision-maker-researcher partnership systematic review. Implementation Science 2011;6:2–17. 10.1186/1748-5908-6-89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Handler SM, Altman RL, Perera S et al. A systematic review of the performance characteristics of clinical event monitor signals used to detect adverse drug events in the hospital setting. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2007;14:451–8. 10.1197/jamia.M2369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donovan JL, Kanaan AO, Thomson MS et al. Effect of clinical decision support on psychotropic medication prescribing in the long-term care setting. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:1005–7. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02840.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Field TS, Rochon P, Lee M et al. Computerized clinical decision support during medication ordering for long-term care residents with renal insufficiency. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009;16:480–5. 10.1197/jamia.M2981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kennedy CC, Campbell G, Garg AX et al. Piloting a renal drug alert system for prescribing to residents in long-term care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011;59:1757–9. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03565.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamblyn R, Eguale T, Buckeridge DL et al. The effectiveness of a new generation of computerized drug alerts in reducing the risk of injury from drug side effects: a cluster randomized trial. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2012;19:635–43. 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Judge J, Field TS, DeFlorio M et al. Prescribers’ responses to alerts during medication ordering in the long term care setting. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2006;13:385–9. 10.1197/jamia.M1945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Statistics Canada. A portrait of seniors in Canada Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Health Canada. Health care system. Secondary Health care system 2004. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/home-domicile/longdur/index-eng.php

- 25.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998;52:377–84. 10.1136/jech.52.6.377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samoocha D, Bruinvels DJ, Elbers NA et al. Effectiveness of web-based interventions on patient empowerment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR 2010;12:e23 10.2196/jmir.1286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Handler SM, Hanlon JT, Perera S et al. Assessing the performance characteristics of signals used by a clinical event monitor to detect adverse drug reactions in the nursing home. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2008;6:278–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Rochon P et al. Effect of computerized provider order entry with clinical decision support on adverse drug events in the long-term care setting. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:2225–33. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02004.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berner ES. Clinical decision support systems: state of the art. Rockville, Maryland: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garg AX, Adhikari NKJ, McDonald H et al. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA 2005;293:1223–38. 10.1001/jama.293.10.1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teich JM, Osheroff JA, Pifer EA et al. Clinical decision support in electronic prescribing: recommendations and an action plan. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2005;12:365–76. 10.1197/jamia.M1822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]