Abstract

Objectives. We assessed risk of cigarette smoking initiation among Hispanics/Latinos during adolescence by migration status and gender.

Methods. The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) surveyed persons aged 18 to 74 years in 2008 to 2011. Our cohort analysis (n = 2801 US-born, 13 200 non–US-born) reconstructed participants’ adolescence from 10 to 18 years of age. We assessed the association between migration status and length of US residence and risk of cigarette smoking initiation during adolescence, along with effects of gender and Hispanic/Latino background.

Results. Among individuals who migrated by 18 years of age, median age and year of arrival were 13 years and 1980, respectively. Among women, but not men, risk of smoking initiation during adolescence was higher among the US-born (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.10; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.73, 2.57; P < .001), and those who had resided in the United States for 2 or more years (HR = 1.47; 95% CI = 1.11, 1.96; P = .01) than among persons who lived outside the United States.

Conclusions. Research examining why some adolescents begin smoking after moving to the United States could inform targeted interventions.

Cigarette smoking and tobacco exposure account for nearly 500 000 deaths in the United States each year, or 20% of US deaths annually.1 Every day in the United States nearly 4000 people aged 12 to 17 years smoke their first cigarette, and about 1000 youths become daily cigarette smokers.2 People who begin smoking regularly during adolescence often become addicted by 20 years of age,3 which underscores the importance of examining risk factors for smoking initiation in adolescents. In 2012, the prevalence of cigarette smoking among Hispanic/Latino persons aged 12 to 17 years was estimated to be less than that of non-Hispanic Whites, but higher than among non-Hispanic Blacks and Asians.4 Among Hispanics/Latinos, 5% of youths aged 12 to 17 years, 25% of adults aged 18 to 25 years, and 17% of adults aged 26 years and older were current cigarette smokers.4

Several studies have examined the association of cigarette smoking and birthplace among US Hispanics/Latinos. Most have reported a higher proportion of smokers among US-born than non–US-born Hispanics/Latinos, especially among women. One study found that the risk of smoking initiation was lower for Mexican immigrants who were living in the United States than for the same individuals before migration.5 Several others have suggested that exposure and acculturation to the US environment may increase cigarette smoking behavior in non–US-born populations.6–9 However, these studies did not focus specifically on adolescents.

Few data exist on individuals from different Hispanic/Latino backgrounds. For instance, Puerto Ricans have a high smoking prevalence, are the second-largest group of US Hispanics/Latinos, and frequently migrate between the US mainland and the US territory of Puerto Rico.10 A recent study reported differences in smoking prevalence among adult Hispanics/Latinos by gender and background. For instance, men and women of Puerto Rican and Cuban descent had a higher prevalence of smoking than was found in national data on non-Hispanic Whites. Women of Mexican and Central American background had a lower smoking prevalence than other racial/ethnic groups in the United States.11 A combination of factors, including but not limited to migration to the United States, country or region of origin, and gender, likely affect risk of cigarette smoking initiation and persistence in Hispanics/Latinos.

We assessed the association between migration and time to smoking initiation during adolescence and whether risk of smoking initiation increased with time since migration. We also assessed whether this association differed by gender and Hispanic/Latino background. The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) provided data on large groups of Hispanics/Latinos of various ethnocultural backgrounds. HCHS/SOL participants were aged 18 to 74 years, but we were able to use questionnaire data to determine smoking history during adolescence. We hypothesized that the risk of cigarette smoking initiation during adolescence would be higher in US-born Hispanics/Latinos than in those born outside the 50 states and Washington, DC; that among individuals born outside the United States, this risk would increase with time since migration to the mainland United States; and that the risk of smoking initiation during adolescence might be modified by gender and Hispanic/Latino background. The HCHS/SOL cohort provided a unique opportunity to address this question in a heterogeneous group of Hispanics/Latinos and to compare associations across many different backgrounds.

METHODS

HCHS/SOL is a community-based study of 16 415 Hispanic/Latino adults living in Bronx, New York; Chicago, Illinois; Miami, Florida; and San Diego, California.12 The study selected households with a stratified, 2-stage area probability sampling design in each of the 4 field centers.13 The first stage randomly selected census block groups stratified by Hispanic/Latino concentration and proportion of high and low socioeconomic status (defined by level of education). The second sampling stage randomly selected households, with stratification, from US Postal Service registries that covered the randomly selected census block groups. Both stages oversampled certain strata to increase the likelihood that a selected address yielded a Hispanic/Latino household.

After this household sampling, study staff made in-person or telephone contacts to screen eligible households and to list their members. Finally, the study oversampled persons aged 45 to 74 years (n = 9714; 59.2%) to facilitate examination of target outcomes. Oversampling at both stages of sample selection increased the likelihood that a selected address yielded an eligible household.

The study weighted all analyses to account for the disproportionate selection of the sample and to at least partially adjust for any bias effects caused by differential nonresponse in the selected sample at the household and person levels. The researchers also trimmed the adjusted weights to limit precision losses resulting from the variability of the adjusted weights, and calibrated to the 2010 Census characteristics by age, gender, and Hispanic/Latino background in each field site’s target population. All analyses also accounted for cluster sampling and the use of stratification in sample selection.

Eligible HCHS/SOL participants were aged 18 to 74 years at the time of screening in 2008 to 2011, self-identified as Hispanic/Latino, could complete a study examination, and reported no plans to move from the study area. Among persons who fulfilled the eligibility criteria and were screened, 41.7% were enrolled. Participants completed a clinic visit that comprised a physical examination, blood collection, and completion of a questionnaire with an interviewer.

For our analysis, we excluded 157 participants who reported beginning cigarette smoking prior to 10 years of age, because it has been shown that most cigarette smoking initiation occurs after this age,14 and we were uncertain about the accuracy of reporting smoking at such a young age. We excluded an additional 257 participants who were missing data on cigarette smoking status, age of smoking initiation, age of migration to the United States, country of birth (US-born vs non–US-born), or Hispanic/Latino background.

Variables

Sociodemographic variables were age at time of examination, gender, self-reported personal or family Hispanic/Latino background (Central American, South American, Cuban, Dominican, Mexican, Puerto Rican, or other/> 1 heritage), field center (Bronx, Chicago, Miami, or San Diego), birthplace (US-born, defined as born in the 50 states or Washington, DC; or non–US-born, defined as born in another country or a US territory, including Puerto Rico), and birth decade (1930s–1990s). Respondents born outside the United States self-reported their age of migration to the United States. We defined ever smoking as individuals’ report of smoking at least 100 cigarettes during their lifetime. Among ever smokers, cigarette smoking initiation age was the self-reported age of starting to smoke cigarettes “de manera regular“ (Spanish) or “fairly regularly” (English).

HCHS/SOL conducted a repeatability study with 60 participants, who repeated an entire clinic examination 4 to 8 weeks after the initial clinic visit. Among persons who reported ever smoking cigarettes, the age when they started to smoke regularly was highly reliable: an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.89 and a coefficient of variation of 6.3%. Among all HCHS/SOL participants, 20% gave questionnaire responses in English.

Statistical Methods

To compare sociodemographic characteristics of US-born and non–US-born individuals, we used the Student t test for continuous normally distributed variables and the Rao–Scott χ2 test for categorical variables. Similarly, we compared these characteristics among non–US-born individuals who came to the United States aged 13 years or older and who came when they were younger than 13 years.15,16 To compare age- and gender-adjusted sociodemographic characteristics across Hispanic/Latino backgrounds, we used analysis of variance for normally distributed continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables.

We created a retrospective cohort design with age as the time metric, beginning at 10 years and right-censoring at 18 years for each individual, because we were interested in modeling the risk of cigarette smoking initiation during adolescence. Among non–US-born individuals, for each year at risk, we determined whether people living in their place of origin outside the 50 states had migrated to the United States recently (within the past 2 years) or had migrated to and resided in the United States for 2 or more years. We therefore considered migration status a time-dependent variable. For instance, a person who reported migrating to the United States at 15 years of age and initiating smoking at 17 years of age would be included in the analysis from 10 years of age until experiencing the event at 17 years of age (as living in the country of birth from 10 to 15 years of age and then as having come to the United States 0 to 2 years ago, from 15 to 17 years of age). A person who reported migrating to the United States at 11 years of age and smoking at 16 years of age would be included in the analysis from 10 years of age until experiencing the event at 16 years of age (as living in the country of birth from 10 to 11 years of age, then having come to the United States 0 to 2 years ago, from 11 to 13 years of age, then having come to the United States 2 or more years ago from 13 to 16 years of age; Figure A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

We used programming statements in PROC SURVEYPHREG in SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) to create the time-dependent migration status variables.17 We used multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models to assess the association between migration status and cigarette smoking initiation between 10 and 18 years of age. We adjusted all models for gender, Hispanic/Latino background, and birth decade. To assess the possibility of different associations between migration status and cigarette smoking initiation between genders and across Hispanic/Latino backgrounds, we included interaction terms. We tested the proportional hazards assumption by including the interaction between migration status and the natural log of time in the model. We considered nonsignificance of these interaction terms to indicate lack of evidence for departure from the proportional hazards assumption. We conducted sensitivity analyses by right-censoring at 25 rather than at 18 years of age. The main findings were similar for both approaches, and therefore we reported only the results from the analysis that right-censored observations at 18 years of age.

All analyses used methods that accounted for the complex survey design and sampling weights of HCHS/SOL, to ensure accurate estimation of variances and valid inferences from hypothesis tests. We adjusted sampling weights (the inverse probability of selection) for each individual for survey nonresponse, trimmed to handle the extreme values of weights, and calibrated to the 2010 US Census gender and age distribution of the target population (all noninstitutionalized Hispanics/Latinos aged 18 to 74 years in the census block groups in the 4 field centers). We included stratification and cluster variables in all analyses to specify the sampling design.13 We weighted all results appropriately, unless otherwise noted. We used SAS version 9.3 for all analyses. Data for all analyses came from HCHS/SOL data release 2 (August 1, 2011).

RESULTS

The study sample comprised 16 001 HCHS/SOL participants (2801 US-born and 13 200 non–US-born), who were aged 18 to 74 years at the time of screening. Non–US-born individuals were older at the time of interview and, among persons who were smokers, non–US-born individuals reported initiating cigarette smoking slightly later than US-born Hispanics/Latinos (Table 1). Around 40% of both non–US-born and US-born individuals reported ever smoking, and just more than 40% reported having a Mexican background (Table 1). Among all migrants, the unweighted median year of migration was 1993 and the median age of migration was 27 years. Among those who migrated at 18 years of age or younger, the unweighted median year of migration was 1980 and the unweighted median age of migration was 13 years.

TABLE 1—

Study Population Characteristics by Country of Birth and Age of Migration: Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos, 2008–2011

| Non–US-Born, Age of Migration |

||||||

| Characteristic | US-Born (n = 2801),a Mean (SE) or No. (%) | Non–US-Born (n = 13 200),b Mean (SE) or No. (%) | Pc | < 13 y (n = 1439), Mean (SE) or No. (%) | ≥ 13 y (n = 11 761), Mean (SE) or No. (%) | Pc |

| Age, y | 31.1 (0.30) | 43.5 (0.26) | < .01 | 35.4 (0.60) | 44.8 (0.27) | < .01 |

| Male gender | 1226 (52) | 5133 (47) | < .01 | 587 (44) | 4546 (47) | .1 |

| Ever smoker | 1223 (40) | 4909 (37) | .05 | 572 (34) | 4337 (37) | .13 |

| Cigarette smoking initiation age,d y | 17.1 (0.20) | 17.8 (0.10) | < .01 | 17.4 (0.30) | 17.8 (0.11) | .13 |

| Hispanic/Latino background | ||||||

| Central American | 79 (2) | 1627 (9) | < .01 | 84 (6) | 1543 (9) | < .01 |

| South American | 45 (1) | 1016 (6) | 52 (3) | 964 (7) | ||

| Cuban | 119 (6) | 2168 (21) | 133 (10) | 2035 (22) | ||

| Dominican | 135 (6) | 1306 (9) | 126 (10) | 1180 (9) | ||

| Mexican | 1057 (41) | 5292 (42) | 501 (39) | 4791 (43) | ||

| Puerto Rican | 1097 (34) | 1570 (11) | 510 (28) | 1060 (8) | ||

| Other/ > 1 | 269 (10) | 221 (2) | 33 (4) | 188 (2) | ||

| Migration age, y | NA | 26.4 (0.30) | NA | 5.9 (0.15) | 29.7 (0.27) | < .01 |

| Field center | ||||||

| Bronx, NY | 1089 (33) | 2900 (23) | < .01 | 517 (34) | 2383 (20) | < .01 |

| Chicago, IL | 599 (25) | 3446 (25) | 329 (24) | 3117 (26) | ||

| Miami, FL | 191 (8) | 3795 (30) | 233 (17) | 3562 (32) | ||

| San Diego, CA | 922 (34) | 3059 (22) | 360 (25) | 2699 (22) | ||

Note. NA = not applicable. All analyses were appropriately weighted to take into account the complex survey design.

Born in the 50 states or Washington, DC.

Born in foreign countries or US territories, including Puerto Rico.

Calculated with the Student t test or Rao–Scott χ2 test, as appropriate.

Log-transformed prior to conducting a t test.

Characteristics relating to cigarette smoking history, migration, and place of residence differed by Hispanic/Latino background (Table 2). Individuals with a Puerto Rican background were more likely than individuals from other backgrounds to be born in the 50 states or Washington, DC, and persons with a Puerto Rican background who moved to the United States tended to do so at a young age (Table 2). Lifetime smoking prevalence was highest among individuals of Puerto Rican and Cuban background (Table 2).

TABLE 2—

Age- and Gender-Adjusted Characteristics by Hispanic/Latino Background: Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos, 2008–2011

| Characteristic | Central American (n = 1706), Mean or % (95% CI) | South American (n = 1061), Mean or % (95% CI) | Cuban (n = 2287), Mean or % (95% CI) | Dominican (n = 1441), Mean or % (95% CI) | Mexican (n = 6349), Mean or % (95% CI) | Puerto Rican (n = 2667), Mean or % (95% CI) | Other/ > 1 (n = 490), Mean or % (95% CI) | Pa |

| Age, y | 39.7 (38.7, 40.7) | 41.9 (40.4, 43.5) | 46.5 (45.5, 47.6) | 39.1 (37.7, 40.4) | 38.3 (37.7, 39.0) | 42.8 (41.8, 43.7) | 34.2 (32.5, 35.8) | < .001 |

| Female gender | 52 (49, 55) | 53 (49, 57) | 47 (44, 49) | 61 (57, 64) | 54 (52, 55) | 48 (46, 51) | 51 (44, 58) | < .001 |

| Mainland US-born | 6 (4, 9) | 7 (5, 9) | 13 (11, 15) | 15 (12, 19) | 20 (18, 22) | 51 (48, 53) | 51 (45, 57) | < .001 |

| Migration age,b y | 27.0 (26.4, 27.7) | 28.3 (27.5, 29.0) | 31.7 (30.8, 32.5) | 25.3 (24.6, 26.0) | 24.5 (24.0, 25.0) | 13.3 (11.9, 14.6) | 23.8 (20.7, 26.8) | < .001 |

| Ever smoker | 29 (26, 32) | 34 (30, 48) | 42 (39, 45) | 24 (21, 27) | 36 (34, 38) | 48 (45, 51) | 43 (37, 50) | < .001 |

| Cigarette smoking initiation age,c y | 18.4 (17.9, 19.0) | 18.1 (17.5, 18.7) | 17.2 (16.8, 17.6) | 17.6 (17.0, 18.2) | 18.1 (17.7, 18.4) | 17.0 (16.6, 17.4) | 17.8 (17.2, 18.5) | < .001 |

| Field center | ||||||||

| Bronx, NY | 18 (13, 22) | 21 (16, 27) | 2 (1, 3) | 94 (91, 96) | 6 (4, 8) | 61 (57, 66) | 37 (29, 45) | < .001 |

| Chicago, IL | 23 (18, 28) | 32 (26, 39) | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 2) | 37 (32, 41) | 33 (28, 37) | 17 (12, 23) | < .001 |

| Miami, FL | 55 (48, 62) | 42 (35, 49) | 96 (95, 98) | 4 (2, 7) | 1 (1, 1) | 4 (2, 5) | 25 (19, 32) | < .001 |

| San Diego, CA | 4 (2, 6) | 4 (1, 6) | 0 (0, 0) | 1 (0, 1) | 56 (51, 61) | 2 (1, 4) | 20 (14, 27) | < .001 |

Note. CI = confidence interval. All analyses were appropriately weighted to take into account the complex survey design. Results adjusted to the overall study population mean age (40.64 years) and proportion of female participants (51.9%).

Calculated with analysis of variance or χ2 test, as appropriate.

Reported only for individuals born outside the 50 US states and Washington, DC.

Reported only for self-reported ever smokers.

We used Cox proportional hazards regression models to assess the association of birthplace and migration status with risk of cigarette smoking initiation between 10 and 18 years of age. Categories for the birthplace and migration status variable were (1) US birthplace, (2) migration to the United States in the past 2 years, (3) migration to the United States 2 or more years ago, and (4) living in non-US place of birth (reference group).

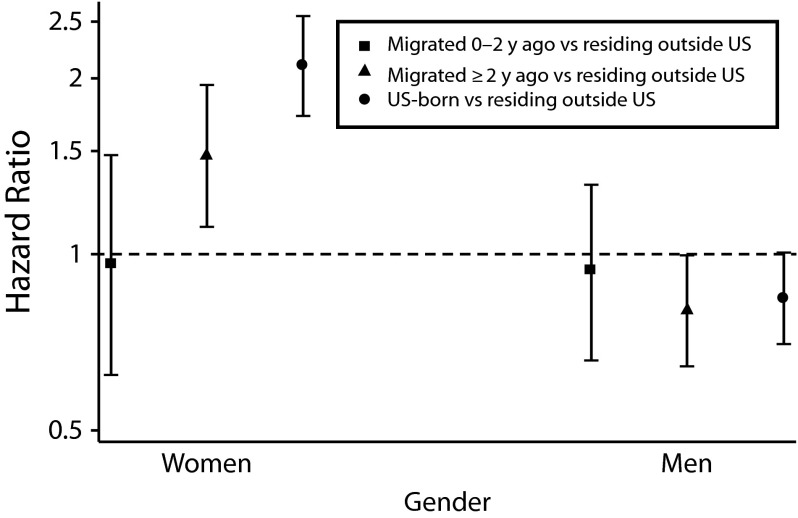

Risk of cigarette smoking initiation during adolescence was higher among women who were born in the United States than who were living outside the United States (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.10; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.73, 2.57; P < .001; Figure 1). Smoking initiation risk was similar among women who had migrated to the United States in the past 2 years and those living in the countries of origin (HR = 0.96; 95% CI = 0.62, 1.48; P = .85). However, non–US-born women who had lived in the United States for 2 or more years had a higher risk of smoking initiation than did those living outside the United States (HR = 1.47; 95% CI = 1.11, 1.96; P = .01), although their risk was lower than that of US-born women.

FIGURE 1—

Association between migration status and risk of cigarette smoking initiation by gender: Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos.

Note. Gender-specific hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals were obtained from a single Cox proportional hazards regression model that included an interaction term between migration status and gender. The model was adjusted for Hispanic/Latino background and decade of birth. The reference group was individuals living outside of the United States (50 states and Washington, DC). The y-axis is on a log scale. Whiskers indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Among men, the risk of cigarette smoking initiation during adolescence was not significantly associated with place of birth or migration variables (Figure 1). Although nonsignificant, the findings were suggestive of an association between migration status and smoking initiation. Risk of smoking initiation during adolescence was similar among respondents who had recently moved to the United States and those who were living outside the United States at a comparable time of adolescence (HR = 0.94; 95% CI = 0.66, 1.32; P = .7). By contrast, men born in the United States tended to have lower risk of cigarette smoking initiation during adolescence than did those who were living outside of the United States at the time (HR = 0.84; 95% CI = 0.70, 1.01; P = .07). Non–US-born men who had lived in the United States for 2 or more years also tended to have lower risk of smoking initiation during adolescence than those who were living outside of the United States at the time (HR = 0.80; 95% CI = 0.64, 1.00; P = .05).

In addition to effect modification by gender, we found evidence of statistical interaction between migration status and Hispanic/Latino background, which was greater among men than women. Among women of almost all background groups studied (except those of South American background, who were relatively few), risk of cigarette smoking initiation during adolescence was higher for US-born than non–US-born individuals (Table 3). Non–US-born women with a Dominican Republic, Mexican, or Puerto Rican background who had lived in the United States for 2 or more years had a higher risk of cigarette smoking initiation during adolescence than those who lived outside the United States at comparable ages (HR = 2.99; 95% CI = 1.69, 5.30; HR = 1.42; 95% CI = 1.01, 2.00; HR = 1.40; 95% CI = 1.01, 1.95, respectively; Table 3).

TABLE 3—

Cox Proportional Hazards Models of the Association Between Migration Status and Risk of Cigarette Smoking Initiation by Gender and Hispanic/Latino Background: Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos

| Men |

Women |

|||

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Central American (n = 671 male, 1035 female) | ||||

| Live outside US (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Came to US in past 2 y | 0.87 (0.37, 2.04) | .75 | 0.90 (0.30, 2.64) | .84 |

| Came to US ≥ 2 y ago | 0.91 (0.48, 1.71) | .76 | 1.59 (0.78, 3.24) | .2 |

| Born in USa | 1.08 (0.55, 2.15) | .82 | 2.71 (1.37, 5.37) | < .01 |

| Cuban (n = 1063 male, 1224 female) | ||||

| Live outside US (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Came to US in past 2 y | 1.03 (0.54, 1.97) | .93 | 1.06 (0.46, 2.46) | .89 |

| Came to US ≥ 2 y ago | 0.57 (0.36, 0.91) | .02 | 1.00 (0.62, 1.61) | > .999 |

| Born in USa | 0.69 (0.45, 1.07) | .1 | 1.73 (1.13, 2.65) | .01 |

| Dominican (n = 500 male, 941 female) | ||||

| Live outside US (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Came to US in past 2 y | 1.04 (0.38, 2.82) | .94 | 1.07 (0.34, 3.37) | .91 |

| Came to US ≥ 2 y ago | 1.71 (0.96, 3.05) | .07 | 2.99 (1.69, 5.30) | < .01 |

| Born in USa | 2.43 (1.23, 4.79) | .01 | 6.06 (2.93, 12.54) | < .01 |

| Mexican (n = 2370 male, 3979 female) | ||||

| Live outside US (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Came to US in past 2 y | 0.89 (0.54, 1.47) | .64 | 0.91 (0.57, 1.47) | .7 |

| Came to US ≥ 2 y ago | 0.81 (0.59, 1.12) | .2 | 1.42 (1.01, 2.00) | .04 |

| Born in USa | 0.65 (0.48, 0.87) | < .01 | 1.62 (1.26, 2.08) | < .01 |

| Puerto Rican (n = 1103 male, 1564 female) | ||||

| Live outside US (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Came to US in past 2 y | 0.97 (0.59, 1.58) | .9 | 1.00 (0.56, 1.78) | .99 |

| Came to US ≥ 2 y ago | 0.80 (0.56, 1.16) | .24 | 1.40 (1.01, 1.95) | .04 |

| Born in USa | 1.00 (0.79, 1.26) | > .999 | 2.50 (1.91, 3.27) | < .01 |

| South American (n = 430 male, 631 female) | ||||

| Live outside US (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Came to US in past 2 y | 1.47 (0.34, 6.29) | .61 | 1.51 (0.37, 6.18) | .57 |

| Came to US ≥ 2 y ago | 0.65 (0.31, 1.36) | .25 | 1.14 (0.53, 2.43) | .74 |

| Born in USa | 0.78 (0.33, 1.80) | .55 | 1.94 (0.85, 4.41) | .11 |

Note. CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio. All analyses were appropriately weighted to take into account the complex survey design. Results were adjusted for decade of birth.

Born in the 50 states or Washington, DC.

Group-specific analyses suggested more similarities across Hispanic/Latino background among women than men (Table 3). Among US-born men, those of Mexican background had significantly lower and those of Dominican background had significantly higher risk of cigarette smoking initiation than did those who lived in Mexico or the Dominican Republic, respectively, at comparable ages. Among men of Cuban background, we observed a trend toward lower risk of smoking initiation for persons born in the United States than for those living in Cuba at the time (P = .1), as well as significantly lower risk of smoking initiation in those who migrated to and had been living in the United States for 2 or more years (P = .02). Among men of Central or South American or Puerto Rican background, we observed no statistically significant association between birthplace or migration status and smoking initiation during adolescence.

DISCUSSION

In a large study of Hispanic/Latino persons, risk of cigarette smoking initiation during adolescence varied by country of residence, gender, and Hispanic/Latino background. In general, women born and living in the 50 states and Washington, DC, had twice the risk of smoking initiation as those living in foreign countries or Puerto Rico. Among non–US-born women, smoking initiation risk increased with duration of residence in the United States. Among men, however, we found no statistically significant overall relationship between birthplace or migration status and smoking initiation during adolescence. These results suggest that in Hispanic/Latino non–US-born populations, and especially among women, living in the United States for a longer period during childhood and adolescence may increase the risk of initiating cigarette smoking by 18 years of age.

Our results are in line with several other studies of Hispanics/Latinos that have found an interaction between gender and migration status. For instance, studies by Marin et al.18 and Perez-Stable et al.19 of predominantly Mexican and Central American populations found that Hispanic/Latino women who were more acculturated were more likely to smoke and that Hispanic/Latino men who were more acculturated were less likely to smoke. Our analyses also suggest that the effect of the US social environment on smoking among Mexican immigrants may vary by gender.20

The interaction between gender and migration status may be partly attributable to gender differences in smoking prevalence in countries of origin (Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Hispanic/Latino non–US-born individuals who have lived in the United States for a longer period may have assimilated to cultural and behavioral norms in the United States, and those who have only recently migrated may exhibit behaviors that are more similar to the norms in their native country. Adolescents who have migrated to the United States may tend over time to adopt the cultural norms of the United States.8,21 Therefore, risk of cigarette smoking initiation may depend on whether the gender-specific smoking prevalence of the country of origin is higher or lower than that of the United States.

Our work extends findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, which examined a cohort of US-born and non–US-born adolescents that consisted of Hispanics/Latinos of Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Cuban descent. Analyses of that study's data have reported that US-born adolescents were more likely than non–US-born adolescents to smoke and that cigarette smoking during adolescence increased, regardless of Hispanic/Latino background, with increased time of residence in the United States.22,23 The large and diverse HCHS/SOL study population provided some insights into how the relationship between birthplace, migration, and cigarette smoking may vary in different sectors of Hispanic/Latino communities. Although our findings were similar to those from the adolescent health study among women (i.e., relationships were similar across Hispanic/Latino backgrounds), among men we observed different patterns of association between time since migration and risk of smoking initiation by Hispanic/Latino background.

A major strength of our study was that our data came from Hispanics/Latinos of varying backgrounds, as well as both US-born and non–US-born individuals. In addition, many previous studies have looked cross-sectionally at prevalence of cigarette smoking; we recreated a data set that enabled us to prospectively assess the risk of smoking initiation between 10 and 18 years of age among persons who were initially nonsmokers at 10 years of age.

Limitations

We focused on cigarette smoking initiation, but further study of alternative forms of tobacco use could be informative. Our power to detect significant associations within each stratum of gender–Hispanic/Latino background might have been limited by relatively small cell sizes. In addition, we might have had less power to detect statistically significant associations among persons of Central American, South American, and Dominican background, because sample sizes were smaller than for other Hispanic/Latino backgrounds. Nonetheless, our results are informative.

We made several assumptions while recreating a time-to-event analysis from a cross-sectional survey. First, we assumed that self-reported age of smoking initiation and year of migration were accurate, although some individuals might not have remembered the exact age at which these events occurred. Second, we used information reported by migrants to the United States to estimate the occurrence of smoking initiation among adolescents living outside of the United States. Third, persons who migrate to the United States during adolescence may be systematically different from those who migrate as adults. However, we were unable to account for characteristics at the time of adolescence because of the retrospective nature of the study.

Conclusions

Migration and acculturation to the United States may engender complex relationships between various social, political, and economic constraints for Hispanics/Latinos of different national backgrounds, leading to varying health behaviors and outcomes.24 Nonetheless, we demonstrated that among US-born and non–US-born Hispanics/Latinos, patterns of association between migration status and risk of adolescent cigarette smoking initiation are gender and background specific.

Additional research to examine why Hispanics/Latinos from certain regions have increased risk of cigarette smoking initiation during adolescence would be useful in creating culturally tailored and targeted intervention and prevention programs.

Acknowledgments

The HCHS/SOL was supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) to the University of North Carolina (N01-HC65233), University of Miami (N01-HC65234), Albert Einstein College of Medicine (N01-HC65235), Northwestern University (N01-HC65236), and San Diego State University (N01-HC65237). The following contribute to the HCHS/SOL baseline examination through a transfer of funds to the NHLBI: National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institute of Deafness and Other Communications Disorders, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke, and Office of Dietary Supplements.

This work was presented at the American Heart Association Epi/NPAM meeting; March 19–22, 2013; New Orleans, LA.

We thank the staff and participants of HCHS/SOL for their important contributions.

The HCHS/SOL investigators: Larissa Avilés-Santa, Paul Sorlie, and Lorraine Silsbee, NHLBI, Bethesda, MD; Robert Kaplan and Sylvia Wassertheil-Smoller, Albert Einstein School of Medicine, Bronx, NY; Martha L. Daviglus, Aida L. Giachello, and Kiang Liu, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and University of Illinois at Chicago; Neil Schneiderman and David Lee, Leopoldo Raij, University of Miami, Miami, FL; Greg Talavera, John Elder, Matthew Allison, and Michael Criqui, San Diego State University and University of California, San Diego; Jianwen Cai, Gerardo Heiss, Lisa LaVange, and Marston Youngblood, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; Bharat Thyagarajan and John H. Eckfeldt, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis; Karen J. Cruickshanks, University of Wisconsin; Elsayed Soliman, Wake Forest University; Hector Gonzales, Thomas Mosley, University of Mississippi Medical Center; John H. Himes, University of Minnesota; R. Graham Barr and Paul Enright, Columbia University; and Susan Redline, Case Western Reserve University.

Human Participant Protection

The HCHS/SOL protocol was approved by each site’s institutional review board. All participants provided informed consent.

References

- 1.Office on Smoking and Health. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Office of Applied Studies. A Day in the Life of American Adolescents: Substance Use Facts Update. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Preventing tobacco use among young people. a report of the surgeon general. Executive summary. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1994;43(RR-4):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Results From the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stoddard P. Risk of smoking initiation among Mexican immigrants before and after immigration to the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(1):94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lariscy JT, Hummer RA, Rath JM, Villanti AC, Hayward MD, Vallone DM. Race/ethnicity, nativity, and tobacco use among US young adults: results from a nationally representative survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(8):1417–1426. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tong E, Saito N, Tancredi DJ et al. A transnational study of migration and smoking behavior in the Mexican-origin population. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(11):2116–2122. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilkinson AV, Spitz MR, Strom SS et al. Effects of nativity, age at migration, and acculturation on smoking among adult Houston residents of Mexican descent. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(6):1043–1049. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.055319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosdriesz JR, Lichthart N, Witvliet MI, Busschers WB, Stronks K, Kunst AE. Smoking prevalence among migrants in the US compared to the US-born and the population in countries of origin. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e58654. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daviglus ML, Talavera GA, Aviles-Santa ML et al. Prevalence of major cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular diseases among Hispanic/Latino individuals of diverse backgrounds in the United States. JAMA. 2012;308(17):1775–1784. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan RC, Bangdiwala SI, Barnhart JM et al. Smoking among U.S. Hispanic/Latino adults: the Hispanic community health study/study of Latinos. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(5):496–506. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sorlie PD, Aviles-Santa LM, Wassertheil-Smoller S et al. Design and implementation of the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20(8):629–641. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lavange LM, Kalsbeek WD, Sorlie PD et al. Sample design and cohort selection in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20(8):642–649. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilman SE, Abrams DB, Buka SL. Socioeconomic status over the life course and stages of cigarette use: initiation, regular use, and cessation. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(10):802–808. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.10.802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fry R, Lowell BL. Work or Study: Different Fortunes of U.S. Latino Generations. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rumbaut RG. Ages, Life Stages, and Generational Cohorts: Decomposing the Immigrant First and Second Generations in the United States. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ake CF, Carpenter AL. Proceedings of the 11th Annual Western Users of SAS Software, Inc. Users Group Conference. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2003. Extending the use of PROC PHREG in survival analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marin G, Perez-Stable EJ, Marin BV. Cigarette smoking among San Francisco Hispanics: the role of acculturation and gender. Am J Public Health. 1989;79(2):196–198. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.2.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pérez-Stable EJ, Ramirez A, Villareal R et al. Cigarette smoking behavior among US Latino men and women from different countries of origin. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(9):1424–1430. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.9.1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Constantine ML, Adejoro OO, D’Silva J, Rockwood TH, Schillo BA. Evaluation of use of stage of tobacco epidemic to predict post-immigration smoking behaviors. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(11):1910–1917. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abraído-Lanza AF, Chao MT, Flórez KR. Do healthy behaviors decline with greater acculturation? Implications for the Latino mortality paradox. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(6):1243–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gordon-Larsen P, Harris KM, Ward DS, Popkin BM. Acculturation and overweight-related behaviors among Hispanic immigrants to the US: the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(11):2023–2034. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hussey JM, Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Iritani BJ, Halpern CT, Bauer DJ. Sexual behavior and drug use among Asian and Latino adolescents: association with immigrant status. J Immigr Minor Health. 2007;9(2):85–94. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9020-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abraído-Lanza AF, Armbrister AN, Flórez KR, Aguirre AN. Toward a theory-driven model of acculturation in public health research. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(8):1342–1346. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]