Abstract

Objectives. We examined the causes of hospitalization and death of people who inject drugs participating in the Bangkok Tenofovir Study, an HIV preexposure prophylaxis trial.

Methods. The Bangkok Tenofovir Study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted during 2005 to 2012 among 2413 people who inject drugs. We reviewed medical records to define the causes of hospitalization and death, examined participant characteristics and risk behaviors to determine predictors of death, and compared the participant mortality rate with the rate of the general population of Bangkok, Thailand.

Results. Participants were followed an average of 4 years; 107 died: 22 (20.6%) from overdose, 13 (12.2%) from traffic accidents, and 12 (11.2%) from sepsis. In multivariable analysis, older age (40–59 years; P = .001), injecting drugs (P = .03), and injecting midazolam (P < .001) were associated with death. The standardized mortality ratio was 2.9.

Conclusions. People who injected drugs were nearly 3 times as likely to die as were those in the general population of Bangkok and injecting midazolam was independently associated with death. Drug overdose and traffic accidents were the most common causes of death, and their prevention should be public health priorities.

People who inject drugs (PWID) are at higher risk for death than are people of similar age and gender who do not inject drugs.1,2 Studies in Europe and North America have demonstrated high mortality rates and standardized mortality ratios among cohorts of PWID.3–8 Trauma, bacterial and HIV infection, suicide, and drug overdose account for much of the increased mortality risk in these studies.9–13 There have been, however, few reports describing the mortality and morbidity of PWID in Southeast Asia and Thailand.14,15

The Bangkok Tenofovir Study was a phase-3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, endpoint-driven, HIV preexposure prophylaxis trial with variable participant follow-up time conducted from June 2005 to July 2012 that demonstrated that a daily oral dose of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (tenofovir) can reduce HIV transmission among PWID by 49%.16 We have summarized the mortality and morbidity data of 2413 non–HIV-infected PWID who participated in the study. We examined participant demographic characteristics and risk behavior to determine predictors of all-cause mortality and calculated the standardized mortality ratio compared with that of the general population of Bangkok, Thailand.

METHODS

Descriptions of community engagement and enrollment and the safety and efficacy results of the Bangkok Tenofovir Study have been published.16–18 The study was conducted at 17 Bangkok Metropolitan Administration drug treatment clinics in densely populated urban communities of Bangkok. The clinics offer a range of services, including HIV counseling and testing, risk-reduction counseling, social and welfare services, health education, medical care and referrals, methadone treatment, condoms, and bleach to clean injection equipment, with demonstrations of appropriate use. These services are provided free of charge. Thailand’s narcotics law prohibits the distribution of needles to inject illicit drugs, and needles are not provided in the clinics19; however, sterile needles and syringes are available to the public over the counter at low cost (5–10 baht, which equals US $0.12–US $0.25) in pharmacies in Bangkok.

Non–HIV-infected individuals aged 20 to 60 years who reported injecting drugs during the previous year were candidates for the study. We randomly assigned participants in a 1:1 ratio to receive 300 milligrams of oral tenofovir daily or placebo.

Participants completed a questionnaire assessing injecting drug use, needle sharing, sexual activity, and incarceration during the previous 3 months at enrollment and every 3 months thereafter using an audio computer-assisted self-interview. At enrollment and monthly (every 28 days) visits, we assessed participants for adverse events, provided individualized risk-reduction counseling, and tested oral fluid for HIV antibodies (OraSure Technologies, Inc., Bethlehem, PA). We referred newly infected individuals for care according to national guidelines.20 At enrollment, months 1, 2, 3, and every 3 months thereafter, we collected blood for hematologic, hepatic, and renal safety assessment.

Research staff telephoned participants before monthly visits to encourage them to attend the visit and contacted participants who missed visits by telephone or with a home visit if they could not be reached by telephone. Staff reviewed medical records of hospitalized participants to abstract data on the cause of hospitalization. We used autopsy reports (n = 42) or death certificates (n = 65) if an autopsy was not performed to define the cause of death, and we checked the Thailand Public Health Statistics database21 every 6 months during the trial and for 1 year after the trial ended to see if participants who were lost to follow-up had died.

We used the Kaplan–Meier product-limit method to estimate participant survival. We censored data when participants died or at their final study visit. We compared the mortality rate of participants in the study with the rate in the general population of Bangkok during 2008 to 2009 using indirect standardization.21–23 We calculated death rates per 1000 person-years of observation and exact 95% Poisson confidence intervals (CIs) for the death rates and the standardized mortality ratios.24 We used a time-varying covariate proportional hazards model to evaluate baseline demographic characteristics and risk behaviors reported each 3 months during follow-up as predictors of death.25

Time-varying variables included injecting drugs, sharing needles, incarceration, sexual activity, and participating in a methadone program. We included data from participants who died within 3 months of their final study visit; we censored data from participants who died more than 3 months after their final visit at the time of their last visit. We evaluated variables that were associated with death in bivariable analysis (P ≤ .1) using a backward stepwise multivariable model. We included treatment group in all models to control for the randomization of participants to tenofovir or placebo. We used SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for statistical analyses.

RESULTS

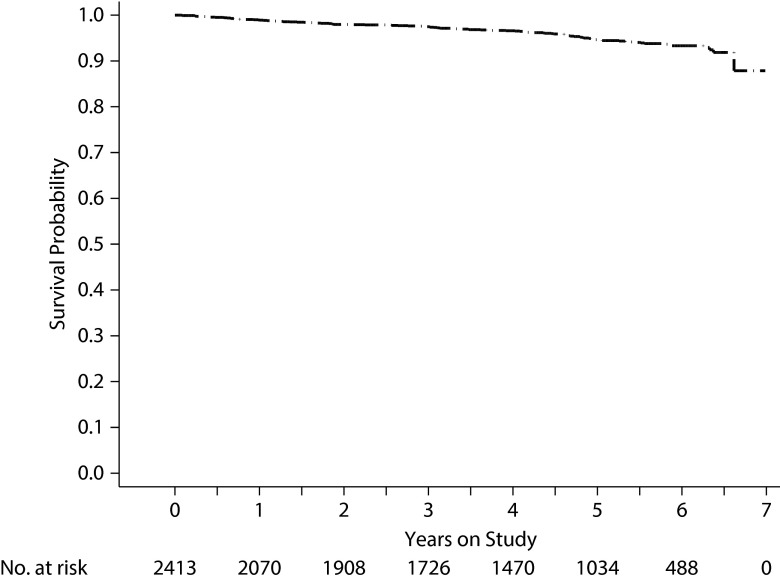

We described study results in previous publications.16–18 Briefly, from June 2005 through July 2010, we evaluated 4094 people for enrollment; 2413 (59.0%) were eligible and enrolled. We followed enrolled participants for an average of 4.0 years (maximum 6.9 years), and participants contributed 9786 person-years of follow-up time. The median age of participants was 31 years (range = 20–59), and 1924 (79.7%) were male. A total of 107 participants died during the trial, 5 (4.7%) of whom we identified in the Public Health Statistics database. The 7-year survival rate using Kaplan–Meier analysis was 87.9% (95% CI = 80.3%, 96.1%; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Kaplan–Meier product-limit survival estimate for injection drug users (n = 2413): Bangkok Tenofovir Study; Bangkok, Thailand; 2005–2012.

At enrollment, 610 (25.3%) participants reported they had been incarcerated in the previous 3 months, 552 (22.9%) in jail, 389 (16.1%) in prison, and 331 (13.7%) in both. Among participants who reported injecting at baseline, 801 (53.2%) injected methamphetamine, 559 (37.1%) midazolam, and 527 (35.0%) heroin. Fifty participants became infected with HIV during follow-up: 17 in the tenofovir group and 33 in the placebo group, indicating a 48.9% reduction in the HIV incidence (95% CI = 9.6, 72.2; P = .01) among participants randomized to tenofovir.16

The frequency of deaths, serious adverse events, and grades 3 and 4 laboratory results were similar among the tenofovir and placebo groups.16 During the trial, 107 participants died: 22 (20.6%) from drug overdose, 13 (12.2%) from traffic accidents, and 12 (11.2%) from sepsis (Table 1). Among the 13 participants who died in traffic accidents, 8 died of head injuries sustained in motorcycle accidents, 3 of other injuries from motorcycle accidents, 1 from a car accident, and 1 from being hit by a train. Three of the 13 had blood or urine examined for drugs and alcohol: 2 had alcohol in their blood, and 1 had methamphetamine in his urine. Nine participants died of cancer: 3 of cancer of the liver, 3 of lung cancer, 1 of rectal cancer, 1 of bone cancer, and 1 of brain cancer.

TABLE 1—

Causes of Death and Hospitalization of Participants (n = 2413): Bangkok Tenofovir Study; Bangkok, Thailand; 2005–2012.

| Variable | No. (%) | Rate per 1000 person-years (95% CI) |

| Cause of death | ||

| All causes | 107 (100.0) | 10.9 (9.0, 13.2) |

| Drug overdose | 22 (20.6) | 2.3 (1.4, 3.4) |

| Suspected drug overdose | 3 (2.8) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.9) |

| Traffic accident | 13 (12.2) | 1.3 (0.7, 2.3) |

| Sepsis | 12 (11.2) | 1.2 (0.6, 2.1) |

| Cancer | 9 (8.4) | 0.9 (0.4, 1.8) |

| Respiratory or circulatory failure | 8 (7.5) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.6) |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 8 (7.5) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.6) |

| Pneumonia | 6 (5.6) | 0.6 (0.2, 1.3) |

| Myocardial infarction | 3 (2.8) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.9) |

| Assault | 3 (2.8) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.9) |

| Drowning | 3 (2.8) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.9) |

| Suicide | 3 (2.8) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.9) |

| Arrhythmia | 2 (1.9) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.7) |

| Peritonitis | 2 (1.9) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.7) |

| Upper gastrointestinal bleed | 2 (1.9) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.7) |

| Other | 8 (7.5) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.6) |

| Cause of hospitalization | ||

| All hospitalizations | 525 (100.0) | 53.7 (49.2, 58.4) |

| Traffic accident | 114 (21.7) | 11.7 (9.6, 14.0) |

| Infection | 104 (19.8) | 10.6 (8.7, 12.9) |

| Drug use | 78 (14.9) | 8.0 (6.3, 10.0) |

| Assault | 54 (10.3) | 5.5 (4.2, 7.2) |

| Gastrointestinal | 24 (4.6) | 2.5 (1.6, 3.7) |

| Psychiatric | 16 (3.1) | 1.6 (0.9, 2.7) |

| Cancer | 14 (2.7) | 1.4 (0.8, 2.4) |

| Heart disease | 14 (2.7) | 1.4 (0.8, 2.4) |

| Other | 107 (20.4) | 10.9 (9.0, 13.2) |

Note. CI = confidence interval.

During the study, 407 participants were hospitalized 525 times (range = 1–5 hospitalizations). The most common causes of hospitalizations were traffic accidents (n = 114; 21.7%), infections (n = 104; 19.8%), drug-related causes (n = 78; 14.9%), and assaults (n = 54; 10.3%; Table 1). The most common grade 3 or 4 laboratory test results were aspartate aminotransferase (182 [7.5%] participants), amylase (153 [6.3%] participants), and alanine aminotransferase (144 [6.0%] participants; Table 2). Grade 4 laboratory events were reported as serious adverse events, and alcohol was recorded as a contributing cause in 75 of 112 (67.0%) grade 4 aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and amylase results; participants could have more than 1 serious adverse event.

TABLE 2—

Grades 3 and 4 Laboratory Results Reported in 12 (0.5%) or More Participants (n = 2413): Bangkok Tenofovir Study; Bangkok, Thailand; 2005–2012

| No. (%) |

|||

| Lab Result | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 3 or 4 |

| AST | 159 (6.6) | 64 (2.7) | 182 (7.5) |

| Amylase | 150 (6.2) | 6 (0.3) | 153 (6.3) |

| ALT | 127 (5.3) | 38 (1.6) | 144 (6.0) |

| Bilirubin | 25 (1.0) | 6 (0.3) | 31 (1.3) |

| Phosphorus | 21 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 21 (0.9) |

| Platelet | 14 (0.6) | 1 (0.1) | 14 (0.6) |

| Hemoglobin | 12 (0.5) | 3 (0.1) | 13 (0.5) |

Note. ALT = alanine aminotransferase; AST = aspartate aminotransferase.

The all-cause mortality rate of participants in the Bangkok Tenofovir Study was 10.9 per 1000 person-years (95% CI = 9.0, 13.2). Multivariable analysis showed that participants aged 40 to 59 years (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.5; 95% CI = 1.4, 4.3) were more likely to die than were participants aged 20 to 29 years and that participants who reported injecting drugs (HR = 2.4; 95% CI = 1.1, 5.4) and, controlling for injecting, those who injected midazolam (HR = 3.6; 95% CI = 1.8, 7.1) were more likely to die than were those who did not (Table 3). Participants who reported sex with a live-in partner were less likely to die (HR = 0.6; 95% CI = 0.4, 1.0) than were those who did not. Among participants who died of overdose or suspected overdose, 20 (80.0%) reported injecting midazolam during the study, 13 (52.0%) injected heroin, and 7 (28.0%) injected methamphetamine.

TABLE 3—

Results of Bivariable and Multivariable Analysis of Baseline Demographic Characteristics and Risk Factors as Predictors of Death Among Injection Drug Users (n = 2413): Bangkok Tenofovir Study; Bangkok, Thailand; 2005–2012

| Bivariable Analysis |

Multivariable Analysis |

||||||

| Variable | Deaths | Person-Years | Deaths per 1000 Person-Years (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P |

| Placebo | 52 | 4207 | 12.4 (9.2, 16.2) | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||

| Tenofovir | 42 | 4183 | 10.0 (7.2, 13.6) | 0.8 (0.5, 1.2) | .308 | 0.9 (0.6, 1.3) | .506 |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 11 | 1745 | 6.3 (3.2, 11.3) | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||

| Male | 83 | 6646 | 12.5 (10.0, 15.5) | 2.0 (1.1, 3.7) | .035 | 1.2 (0.6, 2.5) | .617 |

| Age at enrollment, y | |||||||

| 20–29 | 22 | 3250 | 6.8 (4.2, 10.3) | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||

| 30–39 | 37 | 3162 | 11.7 (8.2, 16.1) | 1.8 (1.0, 3.0) | .038 | 1.4 (0.8, 2.4) | .188 |

| 40–59 | 35 | 1979 | 17.7 (12.3, 24.6) | 2.6 (1.6, 4.5) | < .001 | 2.5 (1.4, 4.3) | .001 |

| Education | |||||||

| ≤ grade 6 | 36 | 4112 | 8.8 (6.1, 12.1) | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||

| > grade 6 | 58 | 4279 | 13.6 (10.3, 17.5) | 1.6 (1.0, 2.4) | .035 | 1.2 (0.8, 1.9) | .353 |

| In jail in past 3 mo | |||||||

| No | 84 | 7444 | 11.3 (9.0, 14.0) | 1.0 (Ref) | |||

| Yes | 10 | 948 | 10.6 (5.1, 19.4) | 0.9 (0.5, 1.7) | .755 | . . . | |

| In prison in past 3 mo | |||||||

| No | 86 | 7379 | 11.7 (9.3, 14.4) | 1.0 | |||

| Yes | 8 | 1013 | 7.9 (3.4, 15.6) | 0.7 (0.3, 1.4) | .299 | . . . | |

| Injected drugs in past 3 mo | |||||||

| No | 33 | 6700 | 4.9 (3.4, 6.9) | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||

| Yes | 61 | 1692 | 36.1 (27.6, 46.3) | 7.2 (4.7, 11.0) | < .001 | 2.4 (1.1, 5.4) | .028 |

| Shared needles in past 3 mo | |||||||

| No | 88 | 8209 | 10.7 (8.6, 13.2) | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||

| Yes | 6 | 183 | 32.9 (12.1, 71.6) | 2.4 (1.0, 5.7) | .045 | 1.0 (0.4, 2.2) | .906 |

| In methadone program | |||||||

| No | 67 | 6407 | 10.5 (8.1, 13.3) | 1.0 (Ref) | |||

| Yes | 27 | 1985 | 13.6 (9.0, 19.8) | 1.3 (0.8, 2.1) | .229 | . . . | |

| Injected heroin in past 3 mo | |||||||

| No | 69 | 7808 | 8.8 (6.9, 11.2) | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||

| Yes | 25 | 584 | 42.8 (27.7, 63.3) | 4.5 (2.8, 7.2) | < .001 | 1.4 (0.8, 2.3) | .211 |

| Injected methamphetamine in past 3 mo | |||||||

| No | 79 | 7768 | 10.2 (8.1, 12.7) | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||

| Yes | 15 | 624 | 24.0 (13.5, 39.7) | 2.1 (1.2, 3.6) | .014 | 0.7 (0.4, 1.2) | .167 |

| Injected midazolam in past 3 mo | |||||||

| No | 43 | 7383 | 5.8 (4.2, 7.9) | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||

| Yes | 51 | 1009 | 50.6 (37.6, 66.5) | 8.5 (5.7, 12.8) | < .001 | 3.6 (1.8, 7.1) | < .001 |

| Had sex in past 3 mo | |||||||

| No | 57 | 3790 | 15.0 (11.4, 19.5) | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||

| Yes | 37 | 4602 | 8.0 (5.7, 11.1) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.8) | .002 | 0.8 (0.5, 1.3) | .324 |

| Had sex with a live-in partner in past 3 mo | |||||||

| No | 66 | 4233 | 15.6 (12.1, 19.8) | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||

| Yes | 28 | 4158 | 6.7 (4.5, 9.7) | 0.4 (0.3, 0.7) | < .001 | 0.6 (0.4, 1.0) | .041 |

| Had sex with a casual partner in past 3 mo | |||||||

| No | 75 | 6713 | 11.2 (8.8, 14.0) | 1.0 (Ref) | |||

| Yes | 19 | 1679 | 11.3 (6.8, 17.7) | 1.0 (0.6, 1.6) | .897 | . . . | |

Note. CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio. The treatment group was included in bivariable and multivariable analyses to control for the randomization of participants to tenofovir or placebo. We analyzed data from participants who died within 3 months of their final study visit (n = 94).

The standardized mortality ratio of participants was 2.9 (95% CI = 2.4, 3.6) compared with the mortality rate of the general population of Bangkok, controlling for gender and age group with indirect standardization.21–23 Consistent with the findings of the multivariable analysis, the standardized mortality ratio comparing women in the study with women in the general population of Bangkok (3.4; 95% CI = 1.7, 6.1) was similar to the ratio of men in the study compared with the general population of men in Bangkok (2.9; 95% CI = 2.3, 3.5).

DISCUSSION

The 7-year Kaplan–Meier survival estimate of participants in this cohort of non–HIV-infected PWID was 87.9%; approximately 1 in 8 participants died during the study. Participants were nearly 3 times as likely to die as were those in the general population of Bangkok. The death rate was higher in men than in women but did not differ significantly in multivariable analysis.

Similar to other studies among PWID, drug overdose, traffic accidents, and sepsis were the most common causes of death.9–12 Eleven of the 13 participants who died in traffic accidents died from motorcycle accidents, and most of these were because of head injuries. Traffic accidents, infections, and drug-related causes were the most common causes of hospitalization. Traffic accidents cause a substantial burden of injury and death in Thailand.26,27 The World Health Organization reports that an estimated 38.1 per 100 000 Thais died in traffic accidents in 2010, the third highest death rate among the 182 countries analyzed.28 Consistent with our findings among PWID, most (74%) traffic accident deaths in Thailand were because of motorcycle accidents.

Controlling for demographic characteristics and injection practices, injecting midazolam—a benzodiazepine with sedative, anxiolytic, and amnestic properties that can cause respiratory depression and arrest29—was independently associated with death. Midazolam use was reported by 80.0% of participants who died of overdose, suggesting that the midazolam that was injected may have been particularly potent, mixed with other drugs, or used in combination with alcohol or other sedative hypnotics, or that the amnestic actions may have led to impaired judgment and overdosing.

Participants reporting sex with a live-in partner were less likely to die than were those who did not report sex with a live-in partner. A previous study among PWID in the same clinics30 found that participants who reported having sex were less likely to become HIV-infected than were those who did not report having sex, suggesting that PWID who have a sexual partner, particularly a live-in partner, are less likely to engage in high-risk behaviors that lead to death or HIV infection.

The mortality rate in this cohort of PWID in Bangkok (10.9 per 1000 person-years; 95% CI = 9.0, 13.2) is lower than was that found in a cohort of non–HIV-infected PWID admitted for treatment of opiate or amphetamine dependence at a drug treatment center in Chiang Mai, Thailand, in 1999 to 2000 (38.5 per 1000 person-years; 95% CI = 24.2, 58.3)14 and a cohort of 690 non–HIV-infected male PWID in Northern Vietnam during 2005 to 2007 (41.1 per 1000 person-years; 95% CI = 26.1, 61.7).15 This suggests that health and harm reduction services may have been more broadly available to PWID in Bangkok in 2005 to 2012 than to PWID in Chiang Mai and Northern Vietnam when those studies were done. The mortality rate in the Bangkok cohort was similar to rates reported in studies among PWID in Australia (8.9 per 1000 person-years; 95% CI = 8.6, 9.2),6 Italy (7.4 per 1000 person-years; 95% CI = 5.9, 8.8),9 and the United Kingdom (10.0 per 1000 person-years; 95% CI = 8.6, 11.5).31

Our analysis has several limitations. A substantial proportion of morbidity and mortality among PWID stems from HIV and HCV infection.11,32,33 We conducted the study in a cohort of non–HIV-infected PWID. Thus, our results are limited to non–HIV-related causes of death and illness. We did not test for HCV infection, but HCV antibody testing of 1209 PWID participating in a 1995 to 1999 preparatory cohort study in the same clinics found an HCV prevalence of 95.6%.30 We suspect that a substantial proportion of participants were infected with HCV and that many of the grade 3 and 4 aminotransferase elevations and possibly the 3 liver cancer deaths were caused by HCV infection.

Participants in our study were willing to come to clinics monthly, were willing to report injection practices, and were able to meet study entry criteria. Their death and hospitalization rates may differ from PWID not in the study, limiting the generalizability of the results. However, using respondent-driven sampling, investigators estimated there were 3595 people injecting drugs in Bangkok in 2004,34 and 4200 in 2009,35 suggesting a large proportion of PWID enrolled in the study allowing generalization of results to PWID in Bangkok.

Among 2413 PWID followed for an average of 4 years, there were 107 deaths, 3 times the expected number of deaths on the basis of data from the general population of Bangkok. The most common causes of death were drug overdose, traffic accidents (i.e., motorcycle accidents), and sepsis; traffic accidents, infections, and drug-related causes were the most common causes of hospitalization. Public health programs that aim to prevent drug overdose, promote safe injection practices,36 and promote road safety, particularly the use of motorcycle helmets, may help reduce mortality and morbidity among PWID in Bangkok.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration. Gilead Sciences donated study medication but was not involved in conducting the study, analysis, or article preparation.

The authors wish to thank the 2413 study participants, many of whom came daily to the study clinics, for their dedication and consistent support. We also want to thank the doctors, nurses, counselors, social workers, research nurses, and staff of the 17 Bangkok Metropolitan Administration Drug-Treatment Clinics, who worked with enthusiasm and grace to make the study a success. We also thank all the members of the study group for their contributions that made the trial possible.

The Bangkok Tenofovir Study Group comprises the following people. The principal investigator is Kachit Choopanya. In the advisory group are Sompob Snidvongs Na Ayudhya, Sithisat Chiamwongpaet, Kraichack Kaewnil, Praphan Kitisin, Malinee Kukavejworakit, Manoj Leethochawalit, Pitinan Natrujirote, Saengchai Simakajorn, and Wonchat Subhachaturas. The study clinic coordination team comprises Suphak Vanichseni (lead); Boonrawd Prasittipol, Udomsak Sangkum, Pravan Suntharasamai; Bangkok Metropolitan (members); and Rapeepan Anekvorapong, Chanchai Khoomphong, Surin Koocharoenprasit, Parnrudee Manomaipiboon, Siriwat Manotham, Pirapong Saicheua, Piyathida Smutraprapoot, Sravudthi Sonthikaew, La-Ong Srisuwanvilai, Samart Tanariyakul, Montira Thongsari, Wantanee Wattana, Kovit Yongvanitjit (administration). The Thailand Ministry of Public Health comprises Sumet Angwandee and Somyot Kittimunkong. The Thailand Ministry of Public Health–US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Collaboration comprises Wichuda Aueaksorn, Benjamaporn Chaipung, Nartlada Chantharojwong, Thanyanan Chaowanachan, Thitima Cherdtrakulkiat, Wannee Chonwattana, Rutt Chuachoowong, Marcel Curlin, Pitthaya Disprayoon, Kanjana Kamkong, Chonticha Kittinunvorakoon, Wanna Leelawiwat, Robert Linkins, Michael Martin, Janet McNicholl, Philip Mock, Supawadee Na-Pompet, Tanarak Plipat, Anchala Sa-nguansat, Panurassamee Sittidech, Pairote Tararut, Rungtiva Thongtew, Dararat Worrajittanon, Chariya Utenpitak, Anchalee Warapornmongkholkul, and Punneeporn Wasinrapee. With the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are Jennifer Brannon, Monique Brown, Roman Gvetadze, Lisa Harper, Lynn Paxton, and Charles Rose. With Johns Hopkins University are Craig Hendrix and Mark Marzinke.

Note. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Human Participant Protection

The ethical review committees of the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration and the Thailand Ministry of Public Health and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s institutional review board approved the study protocol and consent forms. An independent data and safety monitoring board conducted annual safety reviews and 1 interim efficacy review. Participants provided written informed consent.

References

- 1.Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Bucello C, Lemon J, Wiessing L, Hickman M. Mortality among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(2):102–123. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.108282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Degenhardt L, Bucello C, Mathers B et al. Mortality among regular or dependent users of heroin and other opioids: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Addiction. 2011;106(1):32–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antolini G, Pirani M, Morandi G, Sorio C. [Gender difference and mortality in a cohort of heroin users in the provinces of Modena and Ferrara, 1975–1999] Epidemiol Prev. 2006;30(2):91–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer SM, Loipl R, Jagsch R et al. Mortality in opioid-maintained patients after release from an addiction clinic. Eur Addict Res. 2008;14(2):82–91. doi: 10.1159/000113722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciccolallo L, Morandi G, Pavarin R, Sorio C, Buiatti E. [Mortality risk in intravenous drug users in Emilia Romagna region and its socio-demographic determinants. Results of a longitudinal study] Epidemiol Prev. 2000;24(2):75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Degenhardt L, Randall D, Hall W, Law M, Butler T, Burns L. Mortality among clients of a state-wide opioid pharmacotherapy program over 20 years: risk factors and lives saved. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;105(1–2):9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goedert JJ, Fung MW, Felton S, Battjes RJ, Engels EA. Cause-specific mortality associated with HIV and HTLV–II infections among injecting drug users in the USA. AIDS. 2001;15(10):1295–1302. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200107060-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McAnulty JM, Tesselaar H, Fleming DW. Mortality among injection drug users identified as “out of treatment.”. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(1):119–120. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.1.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davoli M, Bargagli AM, Perucci CA et al. Risk of fatal overdose during and after specialist drug treatment: the VEdeTTE study, a national multi-site prospective cohort study. Addiction. 2007;102(12):1954–1959. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frischer M, Goldberg D, Rahman M, Berney L. Mortality and survival among a cohort of drug injectors in Glasgow, 1982–1994. Addiction. 1997;92(4):419–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Phillips B et al. Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet. 2008;372(9651):1733–1745. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Degenhardt L, Hall W, Warner-Smith M. Using cohort studies to estimate mortality among injecting drug users that is not attributable to AIDS. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(suppl 3) doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.019273. iii56–iii63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tyndall MW, Craib KJ, Currie S, Li K, O’Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT. Impact of HIV infection on mortality in a cohort of injection drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;28(4):351–357. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200112010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quan VM, Vongchak T, Jittiwutikarn J et al. Predictors of mortality among injecting and non-injecting HIV-negative drug users in northern Thailand. Addiction. 2007;102(3):441–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quan VM, Minh NL, Ha TV et al. Mortality and HIV transmission among male Vietnamese injection drug users. Addiction. 2011;106(3):583–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03175.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9883):2083–2090. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin M, Vanichseni S, Suntharasamai P et al. Enrollment characteristics and risk behaviors of injection drug users participating in the Bangkok Tenofovir Study, Thailand. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(9):e25127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin M, Vanichseni S, Suntharasamai P et al. Risk behaviors and risk factors for HIV infection among participants in the Bangkok tenofovir study, an HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis trial among people who inject drugs. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e92809. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Office of the Narcotics Control Board, Ministry of Justice. Narcotics Laws of Thailand 2003; Bangkok. Section 93/1.

- 20.Sungkanuparph S, Techasathit W, Utaipiboon C et al. Thai national guidelines for antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 infected adults and adolescents 2010. Asian Biomedicine. 2010;4(4):515–528. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Public Health Statistics. Health Information Unit, Bureau of Health Policy and Strategy. Nonthaburi, Thailand: Thailand Ministry of Public Health; 2010.

- 22.National Statistical Office, Thailand Ministry of Information and Communication Technology. Midyear Population. Bangkok; 2010.

- 23.Curtin LR, Klein RJ. Direct Standardization (Age-Adjusted Death Rates) Hyattsville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services; 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armitage P, Berry G, Matthews JNS. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 4th ed. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1972;34(2):187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hyder AA, Allen KA, Di Pietro G et al. Addressing the implementation gap in global road safety: exploring features of an effective response and introducing a 10-country program. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(6):1061–1067. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chadbunchachai W, Suphanchaimaj W, Settasatien A, Jinwong T. Road traffic injuries in Thailand: current situation. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012;95(suppl 7):S274–S281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. World Health Organization. Global status report on road safety. 2013. Available at: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/road_safety_status/2013/en. Accessed August 1, 2014.

- 29.Roche. Versed (midazolam) injection [package insert]; 2001.

- 30.Vanichseni S, Kitayaporn D, Mastro TD et al. Continued high HIV-1 incidence in a vaccine trial preparatory cohort of injection drug users in Bangkok, Thailand. AIDS. 2001;15(3):397–405. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200102160-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cornish R, Macleod J, Strang J, Vickerman P, Hickman M. Risk of death during and after opiate substitution treatment in primary care: prospective observational study in UK General Practice Research Database. BMJ. 2010;341:c5475. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ly KN, Xing J, Klevens RM, Jiles RB, Ward JW, Holmberg SD. The increasing burden of mortality from viral hepatitis in the United States between 1999 and 2007. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(4):271–278. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-4-201202210-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim AY, Onofrey S, Church DR. An epidemiologic update on hepatitis C infection in persons living with or at risk of HIV infection. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(suppl 1):S1–S6. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wattana W, van Griensven F, Rhucharoenpornpanich O et al. Respondent-driven sampling to assess characteristics and estimate the number of injection drug users in Bangkok, Thailand. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90(2–3):228–233. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnston LG, Prybylski D, Raymond HF, Mirzazadeh A, Manopaiboon C, McFarland W. Incorporating the service multiplier method in respondent-driven sampling surveys to estimate the size of hidden and hard-to-reach populations: case studies from around the world. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(4):304–310. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31827fd650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abdul-Quader AS, Feelemyer J, Modi S et al. Effectiveness of structural-level needle/syringe programs to reduce HCV and HIV infection among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(9):2878–2892. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0593-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]