Abstract

Objectives. We examined disparities in health insurance coverage for racial/ethnic minorities in same-sex relationships.

Methods. We used data from the 2009 to 2011 American Community Survey on nonelderly adults (aged 25–64 years) in same-sex (n = 32 744), married opposite-sex (n = 2 866 636), and unmarried opposite-sex (n = 268 298) relationships. We used multinomial logistic regression models to compare differences in the primary source of health insurance while controlling for key demographic and socioeconomic factors.

Results. Adults of all races/ethnicities in same-sex relationships were less likely than were White adults in married opposite-sex relationships to report having employer-sponsored health insurance. Hispanic men, Black women, and American Indian/Alaska Native women in same-sex relationships were much less likely to have employer-sponsored health insurance than were their White counterparts in married opposite-sex relationships and their White counterparts in same-sex relationships.

Conclusions. Differences in coverage by relationship type and race/ethnicity may worsen over time as states follow different paths to implementing health care reform and same-sex marriage.

Alongside the social determinants of health, lacking health insurance is consistently identified as a driver of health care disparities in the United States.1–4 Without health insurance, people are much less likely to afford and seek medical treatment or maintain a regular medical provider. Yet, data from the 2012 American Community Survey (ACS) indicate that Hispanics (29.1%) and Blacks (19.0%) are much more likely to be uninsured than are Whites (11.1%).5 The reliance on employer-sponsored health insurance (ESI) in the United States exacerbates racial/ethnic disparities in insurance status, as racial/ethnic minorities are more likely to experience spells of unemployment or not hold jobs that offer health insurance.6 Among those with insurance, Blacks and Hispanics are less likely to be covered with private insurance and more likely to be covered through public programs such as Medicare and Medicaid than are Whites.7–9

Individuals in same-sex relationships, or sexual minorities, are also at increased risk for not having health insurance, particularly through employers. Not all employers allow lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB) workers to add a domestic partner to ESI plans. Even among large companies with more than 500 employees, approximately half offer health benefits to same-sex partners.10–12 The federal Defense of Marriage Act, ruled unconstitutional by the US Supreme Court in 2013, added barriers for LGB workers interested in adding a partner to ESI plans. The federal government does not tax employer contributions to an opposite-sex spouse’s health benefits, but under the Defense of Marriage Act, a same-sex partner’s health benefits were taxed (approximately $1000)13 as if the employer contribution was taxable income.

Several studies have indicated that barriers to ESI led LGB persons and adults in same-sex relationships to enroll in public programs or forgo health insurance. Ponce et al., using data from the California Health Interview Survey, found significant disparities in insurance coverage between adults in same-sex partnerships and those in opposite-sex relationships.14 Heck et al., using data from the National Health Interview Survey, found that women in same-sex relationships were less likely to have insurance, to have seen a medical provider in the previous 12 months, and to have a usual source of care than were their counterparts in opposite-sex relationships.15 Federal survey data from the Current Population Survey,16 the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey,17 and the ACS18 show that men and women in same-sex relationships are consistently less likely to have health insurance, particularly through employers.

Not only is having health insurance important for access to health care services, but it has also been independently linked to better health and reduced mortality in vulnerable populations.19 Because of the heavy reliance on ESI in the United States, racial/ethnic minorities as well as sexual minorities are at higher risk for lacking health insurance. Yet, no studies to date have examined disparities in health insurance at the intersections of race/ethnicity and sexual orientation. Much of the available literature has treated adults in same-sex relationships as a single, monolithic population without exploring variation in disparities across different racial/ethnic groups. The 2011 report by the Institute of Medicine on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health identified a need for more research highlighting the intersectional perspectives of individuals who are both sexual minorities and racial/ethnic minorities.20

We examined heterogeneity within lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations by assessing disparities in health insurance status—particularly in ESI—by relationship type and across racial/ethnic identities using information from a large population survey that serves as the nation’s primary data resource on health insurance status and same-sex households.

METHODS

We relied on data from the 2009 to 2011 ACS 3-year public use microdata sample. The ACS is a general household survey conducted by the US Census Bureau and is designed to provide states and communities with reliable and timely demographic, social, economic, and housing information. Replacing the decennial census long-form questionnaire in 2005, the ACS has an annual sample size of about 3 million housing units and a monthly sample of about 250 000 households. The large samples available in the ACS make it a powerful source for studying relatively small subpopulations, such as racial/ethnic minorities in same-sex relationships.21,22

Like most federal surveys, the ACS did not ascertain sexual orientation. Instead, we identified same-sex couples on the basis of intrahousehold relationships. LGB persons were identified when the primary respondent identified another person of the same sex as a husband, wife, or unmarried partner. Until the 2012 ACS, the Census Bureau edited same-sex spouses using the husband or wife response categories as unmarried partners in the public use files regardless of their legal marital status.23 Identification strategies cannot ascertain transgender populations because of the binary male–female categories on gender identity included in the survey. Race/ethnicity was defined with guidelines provided by the US Office of Management and Budget, and each person was assigned to 1 racial/ethnic category: non-Hispanic White; non-Hispanic Black or African American; non-Hispanic Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander (Asian/NHPI); non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN); Hispanic or Latino; and other or multiple non-Hispanic racial/ethnic groups. The small number of NHPIs in same-sex relationships did not support separate stratification, so we combined this group with Asian.

A question regarding health insurance coverage was added to the ACS in 2008 and requires the respondent to report current health insurance status for each member of the household. We used hierarchical assignment to assign each individual to a single source of health insurance coverage, although respondents were able to report multiple sources of coverage. If multiple sources of coverage were reported for an observation, we assigned primary source of coverage in the following order to minimize overestimation in the individual insurance market24: (1) Medicare; (2) ESI, TRICARE or other military health care, or Veterans Affairs (including those who have ever enrolled or used Veterans Affairs health care); (3) Medicaid, Medical Assistance, or any kind of government-assistance plan for those with low incomes or a disability; and (4) insurance purchased directly from an insurance company.25 Consistent with federal definitions,25 we classified observations reporting no source of coverage or only Indian Health Services as uninsured. Insurance and demographic information was available for both partners in each relationship type, so the unit of analysis was each individual, using information on her or his insurance status and race/ethnicity.

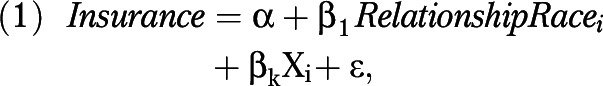

We examined disparities in insurance coverage between adults in same-sex relationships and adults in married and unmarried opposite-sex relationships. First we estimated coverage rates by relationship type and race/ethnicity. Then, we used the following multinomial logistic regression model to control for factors significantly associated with health insurance coverage:

|

where Insurance was 1 of the 4 primary sources of insurance (ESI, directly purchased insurance, Medicaid, or Medicare; uninsured was the reference category) and RelationshipRace indexed the combination of relationship type (same-sex relationship, unmarried opposite sex, or married opposite sex) and race/ethnicity (White, Hispanic, Black, Asian/NHPI, AIAN, or other or multiple races) for each person. The primary reference group included White adults in married opposite-sex relationships. X was the vector of control variables that included age group (25–34, 35–44, 45–54, or 55–64 years), educational attainment (< high school, high school, some college, or ≥ bachelor’s degree), couple’s combined income relative to the federal poverty guidelines as determined by the Department of Health and Human Services in 2009 to 2011 (≤ 100%, 101%–200%, 201%–300%, 301%–400%, and > 400% of the federal poverty guidelines), employment status (full-time employment, part-time employment, unemployed, and not in labor force), industry of employment (government, military, agriculture, mining, construction, manufacturing, wholesale trade, retail trade, transportation, utilities, information, finance, professional, education and health, arts, other, unknown, or not in labor force during previous 5 years), citizenship (citizen, naturalized, or noncitizen), disability status (any difficulties with hearing, vision, remembering or making decisions, walking or climbing stairs, bathing or dressing, or doing errands alone),26 the presence of a biological, adopted, or stepchild younger than 18 years in the household, state of residence, and survey year. We followed our regression models with Wald tests to determine whether there were significant differences between the coefficients of Whites in same-sex relationships and racial/ethnic minorities in same-sex relationships and the coefficients of Whites in unmarried opposite-sex relationships and racial/ethnic minorities in unmarried opposite-sex relationships.

Consistent with previous work,17,18 our sample was restricted to adults aged between 25 and 64 years to account for the completion of educational attainment and Medicare coverage starting at age 65 years. We estimated our models separately for men and women. We have reported the relative risk ratios (RRRs) for each source of insurance, with White individuals in married opposite-sex relationships as the reference group. Our final sample included 15 966 men and 16 778 women in same-sex relationships, of which 3450 men and 3489 women were racial/ethnic minorities. We conducted all coverage estimates and regression models using Stata version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX), with survey weights using Taylor linearized series estimates for SEs.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the primary source of health insurance and sample descriptive statistics for nonelderly partnered adults by relationship type and race/ethnicity. White adults in married opposite-sex relationships have the highest levels of ESI. Approximately 80.0% of White men and women in married opposite-sex relationships are covered though an employer, whereas 72.7% of White men and 74.5% of White women in same-sex relationships are covered through their own or a partner’s workplace. Only 11.0% of White adults in same-sex relationships lacked health insurance.

TABLE 1—

Insurance Coverage and Sample Descriptive Statistics by Gender, Relationship Type, and Race/Ethnicity: American Community Survey, 2009–2011

| Men |

Women |

|||||

| Variable | Same-Sex Relationship, No. or Weighted Mean, % | Opposite-Sex Married, No. or Weighted Mean, % | Opposite-Sex Unmarried, No. or Weighted Mean, % | Same-Sex Relationship, No. or Weighted Mean, % | Opposite-Sex Married, No. or Weighted Mean, % | Opposite-Sex Unmarried, No. or Weighted Mean, % |

| White | 12 516 | 1 062 250 | 92 093 | 13 289 | 1 116 911 | 88 907 |

| ESI | 72.7 | 80.1 | 55.2 | 74.5 | 79.1 | 53.6 |

| Direct purchase | 9.2 | 7.0 | 6.4 | 7.3 | 7.8 | 6.2 |

| Medicaid | 2.9 | 2.4 | 5.3 | 3.8 | 2.7 | 12.5 |

| Medicare | 4.1 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 3.5 | 2.4 | 3.3 |

| Uninsured | 11.1 | 7.7 | 30.2 | 10.9 | 8.0 | 24.5 |

| Couple’s combined income < 100% FPG | 3.3 | 4.3 | 9.6 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 9.7 |

| Employed full time | 69.0 | 77.5 | 68.1 | 66.3 | 47.0 | 55.8 |

| Attained college degree | 51.8 | 37.9 | 22.5 | 52.0 | 37.3 | 26.8 |

| Hispanic | 1 754 | 151 557 | 22 869 | 1 569 | 159 598 | 20 997 |

| ESI | 57.8 | 53.4 | 34.5 | 61.8 | 53.0 | 32.6 |

| Direct purchase | 5.2 | 3.1 | 2.1 | 4.7 | 3.8 | 2.4 |

| Medicaid | 5.8 | 6.3 | 8.0 | 7.5 | 8.1 | 17.1 |

| Medicare | 2.5 | 2.0 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.6 |

| Uninsured | 28.6 | 35.2 | 54.1 | 24.3 | 33.6 | 46.3 |

| Couple’s combined income < 100% FPG | 10.4 | 19.8 | 25.2 | 13.1 | 18.9 | 25.0 |

| Employed full time | 63.7 | 74.3 | 67.3 | 64.0 | 39.7 | 43.1 |

| Attained college degree | 31.1 | 14.5 | 8.0 | 27.9 | 16.9 | 11.0 |

| Black | 753 | 84 920 | 15 830 | 1 109 | 83 559 | 12 419 |

| ESI | 57.3 | 73.7 | 44.5 | 55.9 | 73.6 | 48.0 |

| Direct purchase | 4.2 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 3.2 | 2.5 |

| Medicaid | 10.4 | 5.5 | 10.3 | 13.4 | 6.0 | 19.1 |

| Medicare | 6.1 | 4.5 | 3.5 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| Uninsured | 21.9 | 13.7 | 39.4 | 24.5 | 13.2 | 26.4 |

| Couple’s combined income < 100% FPG | 12.7 | 9.3 | 19.9 | 16.7 | 9.3 | 19.4 |

| Employed full time | 57.0 | 69.0 | 54.8 | 57.0 | 56.8 | 53.8 |

| Attained college degree | 26.9 | 23.6 | 10.5 | 24.3 | 28.4 | 15.3 |

| Asian/NHPI | 595 | 69 730 | 2 787 | 371 | 86 335 | 3 932 |

| ESI | 69.7 | 72.2 | 58.9 | 74.0 | 72.1 | 60.0 |

| Direct purchase | 7.8 | 8.0 | 7.4 | 7.1 | 8.7 | 8.5 |

| Medicaid | 3.2 | 5.4 | 4.9 | 4.4 | 5.3 | 9.0 |

| Medicare | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 0.8 |

| Uninsured | 18.1 | 13.3 | 27.9 | 12.9 | 12.8 | 21.8 |

| Couple’s combined income < 100% FPG | 5.9 | 9.0 | 10.1 | 11.3 | 8.4 | 8.7 |

| Employed full time | 69.4 | 79.6 | 74.3 | 67.7 | 48.7 | 62.4 |

| Attained college degree | 62.5 | 59.3 | 37.7 | 54.1 | 53.9 | 43.5 |

| AIAN | 80 | 8 221 | 1 788 | 126 | 8 883 | 1 845 |

| ESI | 54.2 | 59.8 | 31.3 | 53.5 | 59.4 | 32.9 |

| Direct purchase | 11.6 | 3.3 | 1.5 | 7.1 | 4.1 | 1.6 |

| Medicaid | 6.1 | 7.4 | 14.0 | 5.3 | 7.7 | 22.3 |

| Medicare | 5.1 | 5.8 | 3.8 | 5.5 | 4.3 | 3.0 |

| Uninsured | 23.0 | 23.6 | 49.4 | 28.7 | 24.5 | 40.2 |

| Couple’s combined income < 100% FPG | 4.1 | 14.0 | 28.5 | 16.5 | 13.5 | 25.8 |

| Employed full time | 62.4 | 66.6 | 47.5 | 62.0 | 46.5 | 42.1 |

| Attained college degree | 47.2 | 17.9 | 8.1 | 30.0 | 19.5 | 8.1 |

| Other or multiple races | 268 | 16 520 | 2 445 | 314 | 18 152 | 2 386 |

| ESI | 65.2 | 72.8 | 48.8 | 66.8 | 71.8 | 46.5 |

| Direct purchase | 8.2 | 5.2 | 4.3 | 7.0 | 6.1 | 4.7 |

| Medicaid | 4.2 | 5.3 | 8.1 | 11.0 | 5.8 | 16.7 |

| Medicare | 4.8 | 3.5 | 2.7 | 4.4 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| Uninsured | 17.5 | 13.1 | 36.2 | 10.7 | 13.1 | 28.8 |

| Couple’s combined income < 100% FPG | 4.3 | 8.7 | 13.3 | 11.8 | 8.1 | 13.4 |

| Employed full time | 61.8 | 73.3 | 61.9 | 61.7 | 45.2 | 50.3 |

| Attained college degree | 40.4 | 35.2 | 20.1 | 42.3 | 35.4 | 25.9 |

Note. AIAN = American Indian or Alaska Native; ESI = employer-sponsored health insurance; FPG = federal poverty guidelines (according to the US Department of Health and Human Services); NHPI = Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. Weighted means are for adults aged 25–64 years. FPG determined by the Department of Health and Human Services in 2009–2011.

By contrast, uninsurance was highest among Hispanics in every relationship type. Approximately 29% and 24% of Hispanic men and women, respectively, in same-sex relationships lacked insurance. Yet, the proportion of Hispanics who were uninsured was even higher among adults in married opposite-sex relationships and was highest among adults in unmarried opposite-sex relationships. ESI coverage was relatively low among this sample of Hispanics, especially among Hispanics in unmarried opposite-sex relationships.

ESI coverage was also lower among Black adults, especially those in same-sex or unmarried opposite-sex relationships. Although nearly three quarters of Blacks in married opposite-sex relationships were covered by employers, only 57% of Blacks in same-sex relationships and fewer than half of Blacks in unmarried opposite-sex relationships were covered through ESI. Although ESI was lower for Black men and women in same-sex relationships, they were much more likely to have coverage through Medicaid than were their White counterparts in same-sex relationships and their Black counterparts in married opposite-sex relationships. Similar patterns were found among adults who identified as Asian/NPHI or as other or multiple race categories.

Finally, ESI coverage (∼30%–60%) was lower and uninsurance rates higher for AIAN adults in every relationship type than were those for their White counterparts, particularly among those who were in unmarried opposite-sex relationships. More than 20% of AIAN adults in same-sex relationships and more than 40% of AIAN adults in unmarried opposite-sex relationships lacked health insurance coverage.

Wide differences in socioeconomic status across relationships types have been well documented.18,21,27,28 Similarly, our sample of unmarried adults in opposite-sex relationships were most likely to live in poverty and achieve lower levels of education and employment than were their counterparts in married opposite-sex or same-sex relationships. Although adults in same-sex relationships report higher levels of educational attainment than do their counterparts in married opposite-sex relationships, racial/ethnic minorities in same-sex relationships are more likely to live in poverty and less likely to have a college degree than are their White peers in same-sex relationships. To control for these socioeconomic differences, we determined adjusted RRRs from multinomial logistic regression analyses first for men and then for women.

After controlling for socioeconomic and demographic factors, we found that men in same-sex relationships and unmarried opposite-sex relationships from all racial/ethnic categories were less likely to have health insurance than were White men in married opposite-sex relationships (Table 2). Specifically, men in same-sex relationships were less likely to have ESI coverage or insurance purchased directly from an insurer. Hispanic men in same-sex relationships were much less likely to have insurance through an ESI plan (RRR = 0.38; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.32, 0.46) than were White men in same-sex relationships (RRR = 0.47; 95% CI = 0.44, 0.52). The disparities in ESI between White men in same-sex relationships and Black (RRR = 0.36; 95% CI = 0.27, 0.49), Asian/NHPI (RRR = 0.50; 95% CI = 0.35, 0.71), AIAN (RRR = 0.20; 95% CI = 0.07, 0.54), and other or multiracial (RRR = 0.39; 95% CI = 0.23, 0.65) men in same-sex relationships were not significantly distinguishable. White men in same-sex relationships were more likely to have coverage through Medicaid (RRR = 1.42; 95% CI = 1.18, 1.69) than were White men in married opposite-sex relationships.

TABLE 2—

Multinomial Logistic Regression Analysis of Health Insurance by Relationship Type and Race/Ethnicity Among Nonelderly Men: American Community Survey, 2009–2011

| Variable | Employer vs Uninsured, Adjusted RRR (95% CI) | Direct Purchase vs Uninsured, Adjusted RRR (95% CI) | Medicaid vs Uninsured, Adjusted RRR (95% CI) | Medicare vs Uninsured, Adjusted RRR (95% CI) |

| Married, opposite sex | ||||

| White (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Hispanic | 0.73x (0.71, 0.75) | 0.34x (0.32, 0.36) | 0.66x (0.62, 0.69) | 0.75x (0.71, 0.81) |

| Black | 0.91x (0.88, 0.94) | 0.37x (0.35, 0.39) | 1.30x (1.23, 1.37) | 0.96 (0.90, 1.02) |

| Asian/NHPI | 0.94x (0.90, 0.98) | 0.82x (0.78, 0.87) | 1.39x (1.30, 1.49) | 0.95 (0.85, 1.07) |

| AIAN | 0.39x (0.35, 0.43) | 0.24x (0.20, 0.28) | 0.77x (0.66, 0.89) | 0.53x (0.45, 0.63) |

| Other or multiple races | 0.80x (0.75, 0.86) | 0.61x (0.55, 0.68) | 1.11 (0.99, 1.24) | 0.95 (0.83, 1.09) |

| Same sex | ||||

| White | 0.47x (0.44, 0.52) | 0.64x (0.58, 0.72) | 1.42x (1.18, 1.69) | 0.91 (0.78, 1.06) |

| Hispanic | 0.38x,z (0.32, 0.46) | 0.32x,z (0.24, 0.42) | 0.78z (0.53, 1.14) | 0.48x,z (0.31, 0.75) |

| Black | 0.36x (0.27, 0.49) | 0.30x,z (0.20, 0.46) | 1.47 (0.90, 2.42) | 0.87 (0.56, 1.35) |

| Asian/NHPI | 0.50x (0.35, 0.71) | 0.44x (0.27, 0.72) | 0.77 (0.40, 1.45) | 0.52 (0.20, 1.35) |

| AIAN | 0.20x (0.07, 0.54) | 0.50 (0.20, 1.23) | 1.60 (0.56, 4.59) | 0.64 (0.12, 3.33) |

| Other or multiple races | 0.39x (0.23, 0.65) | 0.49w (0.25, 0.98) | 1.18 (0.55, 2.56) | 0.85 (0.38, 1.92) |

| Unmarried, opposite sex | ||||

| White | 0.25x (0.25, 0.26) | 0.36x (0.25, 0.38) | 0.51x (0.48, 0.53) | 0.42x (0.40, 0.45) |

| Hispanic | 0.31x,z (0.30, 0.33) | 0.18x,z (0.16, 0.20) | 0.46x,z (0.42, 0.49) | 0.41x (0.35, 0.49) |

| Black | 0.26x (0.25, 0.28) | 0.16x,z (0.14, 0.18) | 0.60x,z (0.55, 0.65) | 0.34x,z (0.30, 0.39) |

| Asian/NHPI | 0.41x,z (0.35, 0.48) | 0.48x,z (0.39, 0.59) | 0.64x (0.50, 0.81) | 0.47x (0.29, 0.75) |

| AIAN | 0.16x,z (0.13, 0.19) | 0.07x,z (0.04, 0.13) | 0.50x (0.39, 0.65) | 0.26x,z (0.17, 0.39) |

| Other or multiple races | 0.21x,z (0.18, 0.24) | 0.22x,z (0.17, 0.28) | 0.49x (0.40, 0.62) | 0.40x (0.28, 0.56) |

Note. AIAN = American Indian or Alaska Native; CI = confidence interval; NHPI = Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander; RRR = relative risk ratio. All models controlled for age group, income group, educational attainment, employment status, citizenship status, industry group, presence of a related child younger than 18 years in the household, disability status, state, and survey year.

P < .05; xP < .01 compared with Whites in married opposite-sex relationships.

P < .05; zP < .01 compared with Whites in corresponding relationship type.

Table 3 presents similar findings among women with some notable differences. White (RRR = 0.46; 95% CI = 0.42, 0.50), Hispanic (RRR = 0.43; 95% CI = 0.34, 0.54), Black (RRR = 0.32; 95% CI = 0.24, 0.43), and AIAN (RRR = 0.23; 95% CI = 0.12, 0.45) women in same-sex relationships were significantly less likely to have health insurance through an employer than were White women in married opposite-sex relationships. Differences in ESI were not statistically significant for Asian/NHPI and other or multiracial women in same-sex relationships. Disparities in ESI were significantly wider for Black and AIAN women in same-sex relationships than were those for White women in same-sex relationships.

TABLE 3—

Multinomial Logistic Regression Analysis of Health Insurance by Relationship Type and Race/Ethnicity Among Nonelderly Women: American Community Survey, 2009–2011

| Variable | Employer vs Uninsured, Adjusted RRR (95% CI) | Direct Purchase vs Uninsured, Adjusted RRR (95% CI) | Medicaid vs Uninsured, Adjusted RRR (95% CI) | Medicare vs Uninsured, Adjusted RRR (95% CI) |

| Married, opposite sex | ||||

| White (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Hispanic | 0.69x (0.67, 0.70) | 0.38x (0.36, 0.39) | 0.78x (0.75, 0.82) | 0.68x (0.64, 0.73) |

| Black | 0.88x (0.85, 0.91) | 0.45x (0.43, 0.47) | 1.58x (1.50, 1.66) | 1.47x (1.39, 1.56) |

| Asian/NHPI | 1.08x (1.04, 1.12) | 0.97 (0.92, 1.02) | 1.48x (1.39, 1.57) | 1.11w (1.00, 1.23) |

| AIAN | 0.39x (0.36, 0.43) | 0.27x (0.23, 0.32) | 0.85w (0.74, 0.96) | 0.60x (0.51, 0.72) |

| Other or multiple races | 0.81x (0.75, 0.87) | 0.66x (0.60, 0.73) | 1.16x (1.05, 1.29) | 1.05 (0.92, 1.19) |

| Same sex | ||||

| White | 0.46x (0.42, 0.50) | 0.59x (0.52, 0.66) | 1.29x (1.11, 1.51) | 1.37x (1.18, 1.59) |

| Hispanic | 0.43x (0.34, 0.54) | 0.38x,z (0.28, 0.53) | 1.01 (0.73, 1.39) | 0.84z (0.55, 1.28) |

| Black | 0.32x,z (0.24, 0.43) | 0.16x,z (0.10, 0.28) | 1.63x (1.20, 2.21) | 0.99 (0.63, 1.55) |

| Asian/NHPI | 0.78z (0.47, 1.30) | 0.71 (0.38, 1.33) | 1.38 (0.65, 2.93) | 1.65 (0.57, 4.75) |

| AIAN | 0.23x,z (0.12, 0.45) | 0.43 (0.16, 1.16) | 0.49 (0.18, 1.32) | 1.41 (0.52, 3.83) |

| Other or multiple races | 0.65 (0.40, 1.08) | 0.87 (0.45, 1.70) | 2.79x,z (1.63, 4.76) | 1.82 (0.74, 4.49) |

| Unmarried, opposite sex | ||||

| White | 0.22x (0.22, 0.23) | 0.35x (0.34, 0.37) | 1.65x (1.58, 1.71) | 0.87x (0.82, 0.93) |

| Hispanic | 0.24x,z (0.23, 0.26) | 0.19x,z (0.17, 0.21) | 1.11x,z (1.05, 1.19) | 0.81x (0.70, 0.94) |

| Black | 0.33x,z (0.31, 0.36) | 0.24x,z (0.21, 0.28) | 2.31x,z (2.14, 2.49) | 1.32x,z (1.16, 1.51) |

| Asian/NHPI | 0.37x,z (0.32, 0.42) | 0.55x,z (0.46, 0.66) | 1.78x (1.48, 2.14) | 0.75 (0.49, 1.13) |

| AIAN | 0.17x,z (0.14, 0.20) | 0.09x,z (0.06, 0.15) | 1.34x,y (1.11, 1.62) | 0.50x,z (0.34, 0.74) |

| Other or multiple races | 0.19x,y (0.16, 0.22) | 0.25x,y (0.19, 0.32) | 1.59x (1.32, 1.92) | 0.75 (0.55, 1.03) |

Note. AIAN = American Indian or Alaska Native; CI = confidence interval; NHPI = Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander; RRR = relative risk ratio. All models controlled for age group, income group, educational attainment, employment status, citizenship status, industry group, presence of a related child younger than 18 years in the household, disability status, state, and survey year.

P < .05; xP < .01 compared with Whites in married opposite-sex relationships.

P < .05; zP < .01 compared with Whites in corresponding relationship type.

Furthermore, White (RRR = 0.59; 95% CI = 0.52, 0.66), Hispanic (RRR = 0.38; 95% CI = 0.28, 0.53), and Black (RRR = 0.16; 95% CI = 0.10, 0.28) women in same-sex relationships were less likely to have insurance purchased directly from an insurer than were White women in married opposite-sex relationships. White (RRR = 1.29; 95% CI = 1.11, 1.51), Black (RRR = 1.63; 95% CI = 1.20, 2.21), and other or multiracial (RRR = 2.79; 95% CI = 1.63, 4.76) women in same-sex relationships were more likely to have coverage through Medicaid than were White women in married opposite-sex relationships. Interestingly, White women in same-sex relationships were more likely to have insurance through Medicare than were White women in married opposite-sex relationships, even after controlling for important demographic and socioeconomic characteristics.

Although not our primary focus, racial/ethnic minorities in unmarried opposite-sex relationships were also much less likely to have ESI, insurance purchased directly from an insurance company, and, among men, public coverage through Medicaid. Disparities in ESI were particularly large for AIAN adults in unmarried opposite-sex relationships in our fully adjusted models.

DISCUSSION

Several studies have identified significant disparities in health insurance coverage, particularly in ESI, between adults in same-sex relationships and their counterparts in married opposite-sex relationships. Our results suggest that the experiences of accessing ESI may be different among subgroups in the LGB population, particularly among racial/ethnic minorities. Not only are racial/ethnic minorities less likely to have jobs that offer health insurance or to work enough hours to qualify for health benefits, but many racial/ethnic minorities may struggle to afford health insurance premiums.6 As a result, larger disparities in obtaining ESI may exist for racial/ethnic minorities who also report being in a same-sex relationship.

Indeed, we found that racial/ethnic minority adults in same-sex relationships were much less likely to have ESI than were White adults in married opposite-sex relationships. These gaps in having ESI were much larger for Hispanic, Black, and AIAN adults in same-sex relationships—even after adjusting for socioeconomic and employment status. Interestingly, the population least likely to have private health insurance included racial/ethnic minorities in unmarried opposite-sex relationships, but their lower levels of employment, income, and education may translate into lower levels of ESI coverage.

Our study highlights the necessity of the intersectional perspectives recommended by the Institute of Medicine.20 Health disparity research and research on interventions to ameliorate health disparities should continue to use intersectional approaches that account for the diversity among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people, especially during periods of rapidly evolving health and social policy.

For example, disparities in health insurance for racial/ethnic minorities in same-sex relationships may increase over time as states follow different paths to implementing health care reform and same-sex marriage. Although racial/ethnic minorities in same-sex relationships reside in every state,29–31 only 28 states and the District of Columbia have decided to expand Medicaid to low-income adults through the Affordable Care Act.32–35 Because racial/ethnic minorities represent a disproportionate share of the poor, low-income residents—in same-sex and opposite-sex relationships—those living in states not expanding Medicaid may encounter barriers to obtaining health insurance. Conversely, premium assistance in the Affordable Care Act may help middle-income families purchase private health insurance in the new insurance marketplaces. Recent guidelines from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services now require insurers in the federal and state-based marketplaces to treat same-sex couples as equal to opposite-sex couples.36

Additionally, at the time of this writing, 36 states and the District of Columbia have adopted same-sex marriage laws that extend equal rights and protections to married same-sex couples.37 Although a growing body of evidence suggests that same-sex marriage laws improve LGB health and access to health insurance, no studies have examined the differential impact of same-sex marriage policies within the LGB population.38–40 Researchers should not assume that same-sex marriage benefits the LGB population evenly. Instead, when possible, researchers should approach policy evaluations from an intersectional perspective and identify the specific demographic and socioeconomic subgroups that benefit from policy changes.

Limitations

There were several limitations to using data from the ACS. First, demographers are concerned with data quality when using relationship information to identify same-sex couples. Misreporting gender among married opposite-sex couples, although uncommon, unintentionally includes heterosexuals as false positives among our same-sex partners.23,41,42 The computer-assisted telephone and personal interview versions of the ACS verify the gender of the husband, wife, and unmarried partner if it matches the primary respondent’s gender. After restricting our sample to the respondents using the computer-assisted telephone and personal interview versions of the ACS, we estimated RRRs similar in direction, magnitude, and significance to the results presented in Tables 2 and 3. Additionally, our identification strategy may be missing some same-sex couples. We knew only each person’s relationship to the primary respondent, so our analyses excluded same-sex couples unrelated to the primary respondent or same-sex partners that were identified as a roommate, relative, or nonrelative.

Our study would have benefited from additional information missing in the ACS. For instance, our method of identifying same-sex couples does not verify the sexual orientation of our sample. We assume that people in same-sex relationships are LGB, but bisexual adults were missing from our analysis if they were in an opposite-sex relationship during the survey period. Knowing sexual orientation would have also assisted our analysis of nonpartnered LGB adults.

Furthermore, we did not know the legal status of the same-sex couple’s relationship, and we could not decipher whether a same-sex couple was legally married, was in a state-sanctioned civil union or domestic partnership, or were unmarried cohabitating partners. Before the 2012 ACS, the Census Bureau reassigned same-sex couples identified as husband or wife to unmarried partners without providing edit flags in the public use files. Withholding reassignment flags for these edits in the public use files prevents researchers from examining differences between unmarried same-sex couples and married same-sex spouses. It would be helpful for the Census Bureau to add these edit flags to previously released data, as doing so would facilitate research on trends over time. Finally, the Census Bureau should continue to test and update questions on marital status and relationships that better measure the varying legal status types of same-sex couples.23,43

Notwithstanding these limitations, we leveraged large samples of adults in same-sex relationships in the ACS to document heterogeneous disparities in health insurance for adults in same-sex relationships living in the United States. Further research should continue to explore disparities and interventions that ameliorate disparities in health and access to health care at the intersection of race/ethnicity and sexual orientation.

Conclusions

The LGB population is not a homogenous group. Rather, LGB people and adults in same-sex relationships bear multiple identities that may influence their health and access to care. Using data from the ACS, we found that Hispanics, Blacks, and AIAN adults in same-sex relationships were much less likely to have ESI than were their White counterparts in married opposite-sex and same-sex relationships. This finding contributes to the small, but growing, body of knowledge that individuals at the intersection of race/ethnicity and sexual orientation may be jointly vulnerable to disparities in health and access to care. Future research should continue to explore intersectional disparities and determine how state decisions to legalize same-sex marriage or participate in health care reform differentially affect subgroups within the LGB population.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (grant 65902).

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was needed for this study because the data were obtained from secondary sources.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Hidden Costs, Value Lost: Uninsurance in America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. Health Insurance Is a Family Matter. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine. Coverage Matters: Insurance and Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Smith JC. Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2012. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zuvekas SH, Taliaferro GS. Pathways to access: health insurance, the health care delivery system, and racial/ethnic disparities, 1996–1999. Health Aff (Milwood) 2003;22(2):139–153. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirby JB, Kaneda T. Unhealthy and uninsured: exploring racial differences in health and health insurance coverage using a life table approach. Demography. 2010;47(4):1035–1051. doi: 10.1007/BF03213738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirby JB, Kaneda T. ‘Double jeopardy’ measure suggests Blacks and Hispanics face more severe disparities than previously indicated. Health Aff (Milwood) 2013;32(1):1766–1772. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clemans-Cope L, Kenney GM, Buettgens M, Carroll C, Blavin F. The Affordable Care Act’s coverage expansions will reduce differences in uninsurance rates by race and ethnicity. Health Aff (Milwood) 2012;31(5):920–930. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Claxton G, Rae M, Panchal N . Employer Health Benefits. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Bureau of Labor Statistics. National compensation survey: employee benefits in the United States, March 2011. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2011/ebbl0048.pdf. Accessed September 17, 2014.

- 12.Mercer LLC. US health benefit cost growth slowed again in 2013. Available at: http://www.mercer.com/content/mercer/global/all/en/newsroom/united-states-health-benefit-cost-growth-slowed-again-in-2013.html. Accessed September 17, 2014.

- 13.Badgett M. Unequal Taxes on Equal Benefits: The Taxation on Domestic Partner Benefits. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress; Williams Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ponce NA, Cochran SD, Pizer JC, Mays VM. The effects of unequal access to health insurance for same-sex couples in California. Health Aff (Milwood) 2010;29(8):1539–1548. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heck JE, Sell RL, Gorin SS. Health care access among individuals involved in same-sex relationships. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(6):1111–1118. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.062661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ash MA, Badgett MVL. Separate and unequal: the effect of unequal access to employment-based health insurance on same-sex unmarried and different sex couples. Contemp Econ Policy. 2006;24(4):582–599. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchmueller T, Carpenter CS. Disparities in health insurance coverage, access, and outcomes for individuals in same-sex versus different-sex relationships, 2000–2007. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(3):489–495. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.160804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzales G, Blewett LA. National and state-specific health insurance disparities for adults in same-sex relationships. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):e95–e104. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levy H, Meltzer D. The impact of health insurance on health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:399–409. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Institute of Medicine. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gates GJ. Same-Sex and Different-Sex Couples in the American Community Survey: 2005–2011. Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lofquist D. Same-Sex Couple Households. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeMaio TJ, Bates N, O’Connell M. Exploring measurement error issues in reporting of same-sex couples. Public Opin Q. 2013;77:145–158. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mach A, O’Hara B. Do People Really Have Multiple Health Insurance Plans? Estimates of Nongroup Health Insurance in the American Community Survey. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25. US Census Bureau. ACS health insurance definitions. 2010. Available at: http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/hlthins/methodology/definitions/acs.html. Accessed September 17, 2014.

- 26.Brault MW. Americans With Disabilities: 2010. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Denney JT, Gorman BK, Barrera CB. Families, resources, and adult health: where do sexual minorities fit? J Health Soc Behav. 2013;54(1):46–63. doi: 10.1177/0022146512469629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reczek C, Liu H, Brown D. Cigarette smoking in same-sex and different-sex unions: the role of socioeconomic and psychological factors. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2014;33(4):527–551. doi: 10.1007/s11113-013-9297-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kastanis A, Gates GJ. LGBT African-American Individuals and African-American Same-Sex Couples. Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kastanis A, Gates GJ. LGBT Latino/a Individuals and Latino/a Same-Sex Couples. Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kastanis A, Gates GJ. LGBT Asian and Pacific Islander Individuals and Same-Sex Couples. Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Price CC, Eibner C. For states that opt out of Medicaid expansion: 3.6 million fewer insured and $8.4 billion less in federal payments. Health Aff (Milwood) 2013;32(6):1030–1036. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kenney GM, Dubay L, Zuckerman S, Huntress M. Opting Out of the Medicaid Expansion Under the ACA: How Many Uninsured Adults Would Not Be Eligible for Medicaid? Washington, DC: Urban Institute Health Policy Center; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perkins J. Implications of the Supreme Court’s ACA Medicaid decision. J Law Med Ethics. 2013;41(suppl 1):77–79. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaiser Family Foundation. Status of state action on the Medicaid expansions decision. Available at: http://kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act. Accessed September 17, 2014.

- 36.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Frequently Asked Question on Coverage of Same-Sex Spouses. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Human Rights Campaign. Marriage equality and other relationship recognition laws. Available at: http://hrc-assets.s3-website-us-east-1.amazonaws.com//files/assets/resources/marriage-equality_8-2014.pdf. Accessed September 17, 2014.

- 38.Hatzenbuehler ML, O’Cleirigh C, Grasso C, Mayer K, Safren S, Bradford J. Effect of same-sex marriage laws on health care use and expenditures in sexual minority men: a quasi-natural experiment. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(2):285–291. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wight RG, LeBlanc AJ, Badget MVL. Same-sex legal marriage and psychological well-being: findings from the California Health Interview Survey. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(2):339–346. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buchmueller TC, Carpenter CS. The effect of requiring private employers to extend health benefit eligibility to same-sex partners of employees: evidence from California. J Policy Anal Manage. 2012;31(2):388–403. [Google Scholar]

- 41.DiBennardo R, Gates GJ. US Census same-sex couple data: adjustments to reduce measurement error and empirical implications. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2014;33(4):603–614. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gates GJ, Steinberger M. Same-sex unmarried partner couples in the American Community Survey: the role of misreporting, miscoding and misallocation. Paper presented at the Annual Meetings of the Population Association of America. Detroit, MI; April 30–May 2, 2009.

- 43.DeMaio TJ, Bates N. New Relationship and Marital Status Questions: A Reflection of Changes to the Social and Legal Recognition of Same-Sex Couples in the US. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2012. [Google Scholar]