Abstract

Thanks to the Affordable Care Act, thousands of people living with HIV who have received Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program–funded care are now eligible for Medicaid or subsidized insurance.

The protection against insurance discrimination on the basis of preexisting conditions is increasing health care access for many, but this does not mean that the Ryan White Program is no longer needed. Services essential to improving outcomes on the continuum of HIV care are not supported by any other source.

Because of the growing number of people living with HIV, we must increase funding for the Ryan White Program and increase the number of HIV care providers.

The current period is one of promise and hope as well as uncertainty for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in the United States. Although the country as a whole is witnessing the largest insurance expansion in half a century, the key source of health care access for PLWHA for nearly a quarter century hangs in the balance. The uneven implementation of health care reform—especially in the South, which is largely refusing to expand Medicaid eligibility—will further exacerbate racial and regional disparities in health care access and outcomes.

The 2009 reauthorization of the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program (RWP) expired September 30, 2013, although it continues to be funded. Critical elements of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act ([ACA] Pub. L. No. 111-148, 124 Stat. 855 [March 2010]) took effect in January 2014. Because the ACA expands health care access and provides protections for PLWHA, some have questioned whether we are witnessing the end of the RWP1 and whether it will be needed in the future. However, as President Obama’s 2010 National HIV/AIDS Strategy stated,

Gaps in essential care and services for people living with HIV will continue to need to be addressed along with the unique biological, psychological and social effects of living with HIV. Therefore, the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program . . . will continue to be necessary after the [ACA] is implemented.2

THE RYAN WHITE PROGRAM AND US HIV CARE

To understand the complex and conflicting situation that PLWHA and communities affected by HIV/AIDS are experiencing in 2015, we first have to understand the origins of the RWP. The Ryan White CARE (Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency) Act was passed in fiscal year 1990 (FY1990) to fund community-based HIV care and support services for low-income, uninsured, and underinsured people. Initially funded at $220.0 million, by FY2011 the RWP received $2.3 billion.3,4 As a “payer of last resort,” the RWP “fill[s] the gaps for those who have no other source of coverage or face coverage limits.”5 RWP funding supports the core capacity of community-based providers to offer an integrated care model, including primary medical care, behavioral health, legal assistance, and housing support. The RWP’s AIDS Drug Assistance Program provides medication support to 46% of Americans on antiretroviral treatment.6 More than half a million people receive at least 1 medical, health, or related support service each year through the RWP.6 Two thirds are poor, and three quarters are a racial/ethnic minority (Figure 1).4

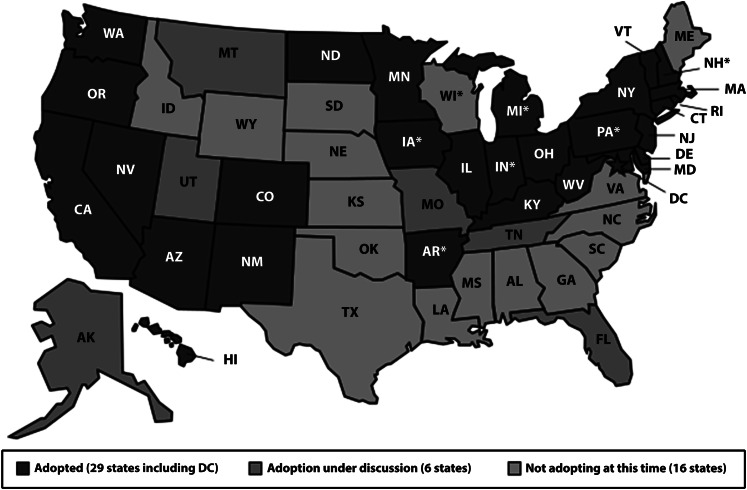

FIGURE 1—

Federal funding for HIV/AIDS care by program in billions of dollars: fiscal year 2012.

Source. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2013, March 5. The Ryan White Program. Fact Sheet. Available at: http://kff.org/hivaids/fact-sheet/the-ryan-white-program. Accessed March 23, 2015.

Most RWP funding goes directly to city and state health departments (Parts A and B, respectively).4 Much of this funding is reallocated to local providers, including AIDS service organizations.

Part C directly funds 350 health care providers, supporting a comprehensive continuum of health care and support services, including outpatient and ambulatory health services, case management and risk reduction counseling (known as early intervention services), medications, medical nutrition therapy, and treatment adherence.4 Part C providers include federally qualified community health centers, AIDS service organizations, family planning agencies, and hospitals.4 Three quarters of a million people are tested for HIV and given risk reduction counseling at Part C providers each year (Table 1).7

TABLE 1—

Ryan White Program Funding

| Ryan White Program | What It Funds | Who Is Funded | Fiscal Year 2012 Final Appropriation, $ |

| Part A | Core medical services (case management, treatment adherence, outpatient and ambulatory health services, etc.), related support services | City health departments, AIDS service organizations in cities with at least 1000 reported AIDS cases | 671 million |

| Part B base | Core medical services, support services | 50 states, DC, territories | 422 million |

| Part B AIDS Drug Assistance Program | HIV medications | 50 states, DC, territories | 933 million |

| Part C | Early intervention services, primary care | 350 federally qualified health centers, AIDS service organizations, hospitals | 215 million |

| Part D | Family services | Public and private organizations | 77 million |

| Part F AIDS Education and Training Centers | Education and training of health providers caring for PLWHA | National, regional education, and training centers | 35 million |

| Part F dental | Dental care | Dental schools and providers | 14 million |

| Part F special projects of national significance | Innovative models of HIV care | Public and private organizations serving PLWHA | 25 million |

| Part F Minority AIDS Initiative | Core medical, support services, outreach | Same as Parts A–C | 426 million |

Note. PLWHA = people living with HIV/AIDS.

Source. Kaiser Family Foundation, Health Resources and Services Administration.

Parts D and F fund family services, education and training, dental care, and special projects addressing emerging issues.4 The Minority AIDS Initiative, spread throughout Parts A–F, funds medical and support services, outreach and education, and early intervention services to address racial/ethnic disparities.4

The essential enabling services funded by the RWP that are not funded by any other source are as follows:

Case management

Treatment adherence counseling

Housing support and advocacy

Some kinds of HIV prevention and testing outreach in nontraditional settings

Legal services and advocacy to help people newly diagnosed with HIV and AIDS access benefits

Food and nutrition services

Dental services

Transportation

Peer support

Risk reduction counseling

Some mental health services

ORIGINAL INTENT AND THE RYAN WHITE PROGRAM TODAY

Before the advent of effective combination antiretroviral therapy in the mid-1990s, HIV usually resulted in highly morbid conditions. Many PLWHA received in-patient medical care. Treatment was largely for AIDS-related health issues. The RWP addressed a structural problem with insurance coverage: its refusal to cover critically necessary enabling and support services that allow people to stay in care. Some 26% of RWP clients are uninsured. About two thirds of current RWP clients have insurance but still rely on the RWP to cover services not covered by their insurance provider.8

Today, most PLWHA receive medical care on an outpatient basis. The RWP is a key funder of outpatient medical care.7 Care managers and care coordinators—roles now being adopted more broadly throughout the health care system—have been essential to the RWP model for nearly a quarter century. As people infected with HIV live longer, they experience increased morbidity from chronic diseases that affect other Americans, such as cardiovascular disease and cancer.

SUCCESSES OF THE RYAN WHITE CARE SYSTEM

The RWP is an effective, comprehensive HIV medical care model. Whereas 49% of all American HIV-infected patients aware of their status are not in ongoing care,9 73% of patients in RWP clinical programs are in continuous care (at least 2 visits, 3 months apart, within the past year).10 Patients involved in stable care have had significant treatment success: 77% are virally suppressed compared with only 28% of all HIV-infected adults in the United States.9

RWP Part C–funded clinics are a key element in the HIV treatment infrastructure. PLWHA often have life challenges and complex comorbidities that complicate their ability to maintain treatment adherence and continuous care. A recent survey of 246 Part C providers found that 20% of their patients had hepatitis B or C, 30% had a substance use disorder, 35% had a serious mental illness, and 39% had received an AIDS diagnosis at the time they entered care.11 For these reasons, the support services funded by the RWP are essential to the success of the core medical services. Social work services and housing assistance funded by the RWP help highly vulnerable PLWHA maintain stability in their lives. Funding for support services allows clinicians to focus on medical care.

THE AFFORDABLE CARE ACT AND HIV

The ACA requires insurance providers to provide insurance for all who apply and to offer comparable rates to all, without regard to preexisting conditions such as HIV infection.12 As of 2013, only 17% of the estimated 1.2 million Americans living with HIV had private insurance, and 30% had no health insurance.13 HIV Health Reform has slightly different figures: 13% of PLWHA have private insurance and 25% do not have any insurance at all. Only 41% of PLWHA in the United States receive regular medical care, and only 28% are virally suppressed.9 Cohen et al. found that earlier treatment decreases HIV transmission, so programs that enhance retention in care may save costs by decreasing HIV incidence.14

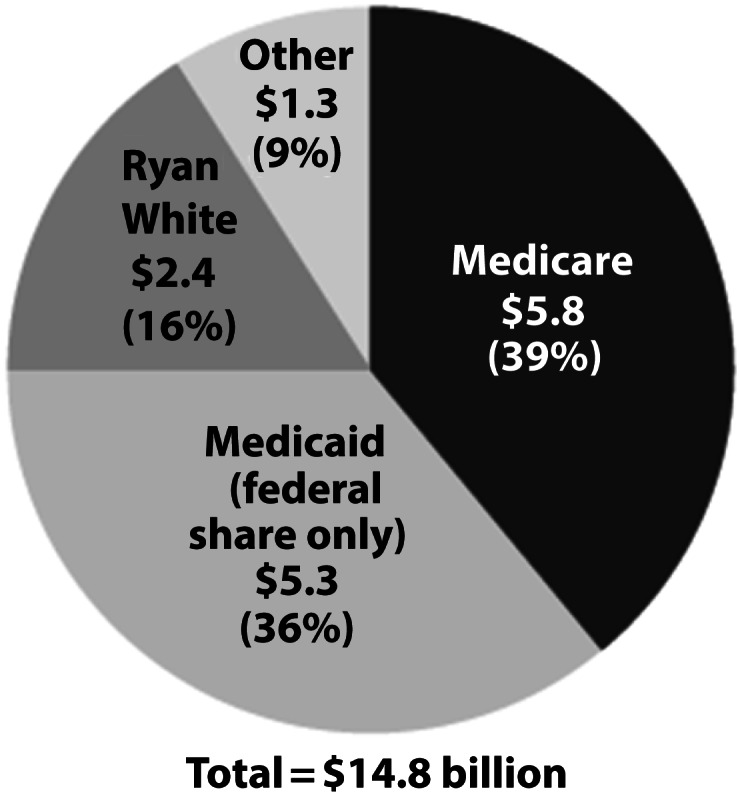

Four in 10 HIV-infected people receive Medicaid, a health insurance program for low-income children, pregnant women, parents, seniors, and people with disabilities.15 However, until the ACA, adults without dependent children living with them or who were not pregnant did not qualify for Medicaid unless they were disabled. For HIV-infected individuals, this meant having an AIDS diagnosis. Under the ACA, states have the option to expand Medicaid eligibility to all adults up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL), as determined each year by the Department of Health and Human Services (Figure 2).13

FIGURE 2—

Current status of state Medicaid expansion decisions: March 6, 2015.

Note. As of March 2015, 6 states were still considering whether or not to expand Medicaid eligibility.

Source. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2015, March 6. Current Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions (map). Available at http://kff.org/health-reform/slide/current-status-of-the-medicaid-expansion-decision. Accessed March 23, 2015.

Other key elements of the ACA include state health insurance marketplaces, through which affordable and often subsidized insurance is offered; the individual mandate to have insurance; a guarantee of access to “essential health benefits,” including preventive services, prescription drugs, and mental health and substance use treatment; and no annual or lifetime limits on how much coverage can be provided.12 These changes will especially help those disproportionately denied insurance coverage and access to health care: PLWHA8 and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people (Table 2).16–18

TABLE 2—

Key Provisions of the Affordable Care Act Important to PLWH

| Provision | Impact |

| Insurance companies prohibited from denying coverage on the basis of preexisting condition | More PLWH will be able to purchase private insurance (currently only 17% have); fewer will have no insurance (currently 30% of PLWH are uninsured) |

| End to annual, lifetime spending caps | Treatment on the basis of standard of care |

| Full coverage of prevention care, such as HIV testing, cancer screening | People will be able to get an HIV test, screened for cancers without copay |

| Coordinated care through health homes, patient-centered medical homes | The Ryan White Program model will be adopted by health care system in general |

| Expansion of eligibility for Medicaid to nondisabled individuals with income below 138% of the federal poverty level13 | PLWH without dependent children and without an AIDS diagnosis will be eligible for Medicaid in many states |

| Prescription drugs, substance use, and mental health services guaranteed as essential health benefits | Expanded access to critical counseling services, medications41 |

Note. PLWH = people living with HIV.

Source. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Pub. L. No. 111-148, 124 Stat. 855 (March 2010).

Why the Ryan White Program Is Still Needed

In 2013, about 30% of people with HIV (some 360 000 individuals) lacked insurance coverage and were not eligible for Medicaid. Many became eligible for Medicaid in 2014. However, the June 2012 US Supreme Court ruling struck down the ACA’s mandatory expansion of Medicaid.19 As of December 2014, 28 states and Washington, DC were expanding Medicaid eligibility, 16 states were not moving forward with the expansion, and 6 states were still debating the issue.20 Many states that have rejected the Medicaid expansion are home to some of the most striking health disparities, particular for racial/ethnic minorities, low-income people, and immigrants. The private insurance premium subsidy covers only people with incomes 400% or less of the FPL. In the 16 states that had not expanded Medicaid as of March 2015, some of the poorest people in those states—nearly 5 million individuals—remain uninsured.20,21

Despite the expansion of access to health care brought about by the ACA, PLWHA will continue to need the critical services funded by the RWP well into this decade and beyond. This is true in all 50 states and especially in the 16 states not currently expanding Medicaid eligibility. In many Southern states, one must be extremely poor and have dependent children to qualify for Medicaid. For example, in Alabama a family of 3 must earn 16% of the FPL or less—$3221 per year—to qualify for Medicaid.21 In Texas a family with dependent children must earn 19% of the FPL or less to be Medicaid eligible.21

Childless, nonpregnant, nondisabled adults in non-Medicaid expansion states cannot qualify, no matter how low their incomes. Many thousands of poor people with HIV are ineligible for Medicaid but do not earn enough (≥ 100% of the FPL) to qualify for subsidies to support their purchase of insurance in the marketplaces. This population falls into what is known as the “coverage gap.” The coverage cap is created by states’ nonexpansion of Medicaid eligibility.21 RWP-funded services will be especially important for this population of PLWHA who cannot access insurance.

Contributing to the increasing complexity of HIV care is the aging of the population of PLWHA. By 2015 or 2017, depending on the estimate, half of the HIV-positive population in the United States will be older than 50 years.22,23 As people grow older with HIV and live decades with the virus, they are likely to develop comorbidities.24 Common comorbid conditions among older adults living with HIV include liver, kidney, and cardiovascular disease; cognitive impairment; depression; and neuropathy.25 Coinfections such as hepatitis C—found among one third of HIV-infected Americans26—are among the causes of comorbidities such as cirrhosis and hepatitis C virus–related mortality.27,28

Learning From the Massachusetts Experience

Although the ACA has removed some barriers to insurance coverage and access to health care, it will not cover all the enabling services funded by the RWP, nor will it cover all the needs of PLWHA. Implementation of the ACA coupled with continued support for the RWP could lead to breakthroughs in HIV care and prevention, if the Massachusetts experience is any indicator. Massachusetts has a strong network of RWP Part C providers. In 2001 Medicaid was expanded up to 200% of the FPL in Massachusetts.29 In 2006 Massachusetts became the first state in the nation to mandate health insurance for all residents. Massachusetts residents earning up to 300% of the FPL are eligible for subsidies to help them purchase private insurance.30 The uninsured rate dropped from 6% in 2006 to 2% in 2010 in Massachusetts. (Nationally 17% of Americans were uninsured in 2010.31)

Numerous advances in HIV prevention and care have occurred over the past decade in Massachusetts. Massachusetts has “significantly higher rates of HIV [virological] suppression” because of “high level of access to quality care,” resulting in earlier initiation of treatment and greater rates of medication adherence.32 Massachusetts’s HIV Drugs Assistance Program transitioned away from being a payer of last resort a decade ago to supporting low- and middle-income PLWHA through copay and premium assistance. A survey of 1791 PLWHA in the Boston area found that 91% of RWP patients reached through the HIV Drugs Assistance Program and case management programs were taking antiretroviral medications, and 72% were virally suppressed.33

Enhanced access to care and proactive prevention programs have been synergistic. For more than a decade Massachusetts has been a leader in syringe exchange; in 2002 it had 6 programs, more than 43 other states.34 Although HIV incidence has remained steady in the United States over the past decade at about 50 000 new infections per year,35 new HIV diagnoses in Massachusetts dropped 45% from 2000 to 2010.36

It is important to note the differences between Massachusetts and the country as a whole. Massachusetts’s reforms were more comprehensive than were those brought about by the ACA nationwide. No regions of Massachusetts could opt out of the expansion of Medicaid eligibility, as nearly half of US states have done—although that number is slowly dwindling, and no group of Massachusetts residents exists in an uninsured no-man’s-land, as do millions of Americans in the states not expanding Medicaid eligibility—they are not poor enough or sick enough to qualify for Medicaid but do not earn enough to qualify for subsidies to purchase insurance in the marketplace. However, if the 28 states performing some form of Medicaid expansion combine these efforts with expanded HIV prevention efforts, we could see a reduction in HIV incidence, a key goal of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy.

How the Ryan White Program and HIV Care Should Change

As providers of HIV prevention and care services working at an RWP Part C provider, a federally qualified health center, and a center for clinical HIV research since the earliest days of the AIDS epidemic,37 we believe that the RWP should change in numerous ways.

Maintain the Ryan White Program and increase funding to support a growing caseload.

The RWP provides critical medical care and necessary support services to more than half a million Americans living with HIV. Necessary support services are not covered by qualified health plans traded on the state or federal insurance marketplaces or by Medicaid. Many PLWHA who have purchased insurance in the marketplaces have trouble affording their medications because of high cost sharing. In May 2014 the National Health Law Program and the AIDS Institute sued 4 Florida insurance companies for allegedly pricing medications in a way that discourages PLWHA from selecting their policies.38

Assistance with prescription medication copays and other supplements may be necessary to enable current RWP clients to transition to insurance purchased in the marketplaces. The RWP and the AIDS Drug Assistance Program can provide copay assistance for PLWHA whose insurance does not fully cover the cost of prescription medications.39 Because two thirds of current RWP clients already have insurance, and because 31% of PLWHA who have insurance also access RWP-funded services, it is likely that those newly insured in 2014 and beyond will continue to need RWP-funded services.8

Despite the challenging fiscal climate, funding for the RWP must increase. Because about 50 000 Americans are newly infected each year and increasingly more people access antiretroviral treatment and live into older adulthood with HIV, the number of PLWHA is projected to increase between 24% and 38% over the next decade, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.40

In inflation-adjusted dollars, funding for the RWP decreased by nearly 10% from FY2003 to FY2007, even as the number of people living with AIDS in the United States during this period increased by 25% because of expanded testing initiatives.41 From 2001 to 2009 the number of patients served by RWP Part C providers grew by 62%, from 158 000 to 255 000, whereas funding grew by only 9%.6 Funding declined from $2.392 billion in FY2012 to $2.319 billion in FY2014.42 The AIDS Budget and Appropriations Coalition requested $2.442 billion for FY2015, some $119.000 million more than President Obama’s budget request.43

Provide culturally competent care through the Ryan White Program for older adults living with HIV.

A second recommendation pertains to older adults living with HIV. Moving forward, increasingly more people accessing RWP services will be in their 50s, 60s, 70s, and 80s. In 2010 47% of RWP clients were aged 45 to 64 years.44 Issues affecting older adults living with HIV include stigma, social isolation, lack of caregiving support networks, polypharmacy, and multiple comorbidities.45

HIV-related stigma is strong among older adults, who are more likely than are their younger cohorts to hold inaccurate beliefs about the casual transmission of HIV.46 Older Americans are also less tolerant of homosexuality.47 This can affect the experiences of older PLWHA, including older gay men, in mainstream senior settings. Older Americans Act funds could support research to better understand how HIV-positive and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender elderly individuals experience mainstream senior services.

Health care and elder service providers should be trained in the unique needs of older adults with HIV. The Health Resources and Services Administration should partner with the Administration on Aging to train elder service providers—including home care aides—about the unique needs and experiences of HIV-positive older individuals as well as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults.45 This would allow older PLWHA to age in place, in their homes. It is also important that health care providers, including behavioral health providers, be trained in the unique issues facing older individuals living with HIV. Social isolation can correlate with depression and substance use, which can affect treatment adherence. Improving treatment outcomes among PLWHA aged 50 years and older requires interventions to reduce social isolation, such as congregate meal programs and friendly visitor programs.45

Improve treatment outcomes and viral suppression rates and incorporate biomedical prevention approaches.

Gardner et al. estimated that only 19% of PLWHA in the United States have an undetectable viral load.48 It is essential that more people with HIV be retained in care and achieve viral suppression. Not only will this improve treatment outcomes, a key goal of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy, but it will also likely reduce incidence, owing to the preventive effect of treatment adherence demonstrated by Cohen et al.14

Our third recommendation is that the Health Resources and Services Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention promote the preventive benefits of HIV treatment and viral suppression, known as “treatment as prevention.” Treatment adherence counseling and medical case management are not new RWP activities; however, the recent evidence that viral suppression helps prevent HIV transmissions is new and should be shared with RWP clients through treatment education. The Health Resources and Services Administration and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should also partner on the roll out of preexposure chemoprophylaxis: taking antiretroviral medications to prevent HIV transmission through unprotected sex or sharing needles.49

Recent models of preexposure chemoprophylaxis implementation, coupled with scaled up HIV treatment, predict significant reductions in HIV incidence and prevalence.50–52 RWP planning councils and prevention planning groups should also work together to ensure success. HIV testers funded by the RWP should encourage high-risk individuals who test negative for HIV to discuss preexposure chemoprophylaxis with their providers. This would be a new activity under the RWP and would require additional funding.

Consider creative approaches to providing Medicaid and marketplace insurance.

Fourth, the Obama Administration and state governments should consider creative approaches to providing health insurance to individuals living with HIV. These could include waiving them into existing Medicaid or providing targeted subsidies to assist low-income individuals in purchasing insurance in the marketplaces. Medicaid is the largest payer of HIV care in the United States. However, the Kaiser Family Foundation estimated in October 2013 that 43% of PLWHA lived in the 25 states that, at that time, were not moving forward with the Medicaid expansion8 (as of March 2015 it was 16 states not moving forward, and 6 states considering expansion).53 Black Americans living with HIV are disproportionately represented in these states, which include nearly all the Southern states.

Essential to being able to access antiretroviral treatment is health insurance coverage, which is why expansion of Medicaid is so critical. We believe that Medicaid expansion and subsidized private health insurance were key factors in Massachusetts’s success in reducing HIV incidence by 45% from 2000 to 2010. Unfortunately Medicaid rules in nonexpansion states create a catch-22 for low-income PLWHA, who cannot qualify for Medicaid until they are very sick (meaning they have an AIDS diagnosis and, often, AIDS-related complications). Current guidelines encourage people to start treatment at diagnosis.54 This both improves treatment outcomes and reduces transmission. Creative solutions to expand insurance coverage for low-income PLWHA are essential.

Support the development of the HIV provider workforce.

The RWP’s essential support for HIV provider workforce development should be made explicit. Part C funding supports 71.0% of HIV clinics’ primary care staff.11 The median caseload for Part C–funded providers was 178 patients per physician. More than 70% of Part C clinics reported an increase in the number of patients they saw from 2004 to 2007; the median increase was 17.5%.55,56 Health care providers with a specialization in HIV care are disproportionately older and nearing retirement age.15

Numerous steps could increase the number of newly trained primary care providers who specialize in HIV care. These include targeted loan forgiveness through the National Health Service Corps for HIV medical providers who work at Part C–funded sites, increased federal support for clinical training opportunities in HIV medicine, and increased Medicaid reimbursement rates for HIV care—all recommendations of the HIV Medicine Association and the American Academy of HIV Medicine.15 These could be included in RWP legislation or in complementary health policy and budget language.

Policymakers should consider other changes to the RWP. Jeffrey Crowley and Jen Kates suggested numerous changes to the RWP in a Kaiser Family Foundation monograph published in April 2013, including the following:

updating the 2006 requirement that 75% of funds be used for core medical services;

strengthening the program’s focus on gay and bisexual men, especially young Black gay and bisexual men;

strengthening jurisdictional planning by making it more evidence based; and

simplifying grantee application and reporting procedures.57

These recommendations are worthy of consideration as well, and we encourage other HIV care providers, advocates, PLWHA, policymakers, and researchers to engage in the policy debate on the future of the RWP plan to ensure adequate health care access and improved treatment outcomes for PLWHA.

CONCLUSIONS

The ACA is dramatically expanding health care access and providing treatment protections for PLWHA. Over the past 2 decades RWP Part C providers have forged a successful HIV care system that has kept hundreds of thousands of people healthy and on treatment. The resistance to Medicaid expansion in 22 states, including most of the South, will severely limit our ability to improve HIV treatment outcomes and reduce health disparities there.56 Many thousands of people no longer need the RWP to pay for their medical care thanks to the new opportunities provided by private insurance traded on the state health insurance marketplaces and the prohibition on denying coverage on the basis of a preexisting condition. We welcome these advances in health policy. However, thousands of people with HIV—disproportionately poor, Black, and gay or transgender—will continue to rely on the RWP for medical care and for critically important enabling services for the foreseeable future.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrea Karis for her research assistance and production assistance.

Human Participant Protection

No human participant protection was required because no human participants were involved in this secondary research review and policy analysis.

References

- 1. McClain M. The end of the Ryan White CARE Act? The Affordable Care Act, Medicaid, and Ryan White. Paper presented at the 13th Annual AIDS Education Month Prevention and Outreach Summit. Philadelphia, PA; June 14, 2012.

- 2.President of the United States, Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States. Available at: http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/NHAS.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2012.

- 3. Boswell S. Health care reform in HIV on the front lines. Paper presented at the Infectious Disease Society of America Annual Meeting. Boston, MA; October 20–23, 2011.

- 4.Kaiser Family Foundation. HIV/AIDS Policy Fact Sheet. The Ryan White Program. Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.HIV/AIDS Bureau, US Department of Health and Human Services. Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program Part A manual. Available at: http://hab.hrsa.gov/tools2/PartA/parta/ptAsec7chap5.htm. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- 6. Cheever L. The evolution of the Ryan White Program under health care reform. Paper presented at IDWeek 2012. San Diego, CA; October 17–21, 2012.

- 7. HIV Medicine Association. Ryan White Program Part C: providing health care to people with HIV/AIDS in underserved communities. Available at: http://www.hivma.org/uploadedFiles/HIVMA/Policy_and_Advocacy/Ryan_White_Medical_Providers_Coalition/Resources/Part_C_Paper_April_2012.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2012.

- 8.Kates J, Garfield R, Youth K Assessing the impact of the Affordable Care Act on health insurance coverage of people with HIV. 2014. Available at: http://kff.org/report-section/assessing-the-impact-of-the-affordable-care-act-on-health-insurance-coverage-of-people-with-hiv-issue-brief. Accessed May 12, 2014.

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: HIV prevention through care and treatment—United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(47):1618–1623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallant JE, Adimora AA, Carmichael JK et al. Essential components of effective HIV care: a policy paper of the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Ryan White Medical Providers Coalition. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(11):1043–1050. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir689. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weddle A, Hauschild B. HIV medical provider experiences: results of a survey of Ryan White Part C programs. Paper presented to the Institute of Medicine, Committee on HIV Screening and Access to Care. Washington, DC; September 29, 2010.

- 12.US Department of Health and Human Services. Key features of the law. Available at: http://www.healthcare.gov/law/features/index.html. Accessed September 17, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13. AIDS.gov. The Affordable Care Act and HIV/AIDS. Available at: http://www.aids.gov/federal-resources/policies/health-care-reform. Accessed January 31, 2013.

- 14.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.HIV Medicine Association. The looming crisis in HIV care: who will provide the care? 2010. Available at: http://www.hivma.org/uploadedFiles/HIVMA/Policy_and_Advocacy/Policy_Priorities/HIV_Medical_Workforce/Briefs/The%20Looming%20Crisis%20in%20HIV%20Care.pdf. Accessed November 12, 2012.

- 16.Ponce NA, Cochran SD, Pizer JC, Mays VM. The effects of unequal access to health insurance for same-sex couples in California. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(8):1539–1548. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cochran SD. Emerging issues in research on lesbians’ and gay men’s mental health: does sexual orientation really matter? Am Psychol. 2001;56(11):931–947. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.56.11.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diamant AL, Wold C, Spritzer K, Gelberg L. Health behaviors, health status, and access to and use of health care: a population-based study of lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual women. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(10):1043–1051. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.10.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Supreme Court of the United States. National Federation of Independent Business et al. v. Sebelius, Secretary of Health and Human Services, et al. No. 11–393 (June 28, 2012).

- 20.Kaiser Family Foundation Current status of the Medicaid expansion decisions. Map. 2015. Available at: http://kff.org/health-reform/slide/current-status-of-the-medicaid-expansion-decision. Accessed March 23, 2015.

- 21.Kaiser Family Foundation. The coverage gap: uninsured poor adults in states that do not expand Medicaid. Issue brief. 2014. Available at: http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/8505-the-coverage-gap_uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2014.

- 22.Effros RB, Fletcher CV, Gebo K et al. Aging and infectious diseases: workshop on HIV infection and aging: what is known and future research directions. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(4):542–553. doi: 10.1086/590150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Justice A. HIV and aging. Projections from 2008 forward based on analysis of trends in 2001–2007 data from CDC surveillance reports. Paper presented at Ryan White All Grantees Meeting; August 26, 2010; Washington, DC.

- 24.Deeks SG, Philips AN. HIV infection, antiretroviral treatment, aging, and non-AIDS related morbidity. BMJ. 2009;338(7689):288–292. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a3172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cahill S, Darnell B, Guidry J . HIV and Aging: Growing Older With the Epidemic. New York, NY: Gay Men’s Health Crisis; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sulkowski MS, Mast EE, Seef LB, Thomas DL. Hepatitis C virus infection as an opportunistic disease in persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(suppl 1):S77–S84. doi: 10.1086/313842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Ledinghen V, Barreiro P, Foucher J et al. Liver fibrosis on account of chronic hepatitis C is more severe in HIV-positive than HIV-negative patients despite antiretroviral therapy. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15(6):427–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00962.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Holmberg SD, Kathleen L, Xing I, Klevens M, Jiles R, Ward JW. The growing burden of mortality associated with viral hepatitis in the United States, 1999–2007. Paper presented at the 62nd Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; November 4–8, 2011; San Francisco, CA.

- 29.Seifert R, Anthony S. The basics of MassHealth. 2011. Available at: http://www.umassmed.edu/uploadedFiles/CWM_CHLE/Included_Content/Right_Column_Content/MassHealth%20Basics%202011-FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 8, 2012.

- 30.Raymond A. The 2006 Massachusetts Health Care Reform Law: progress and challenges after one year of implementation. 2007. Available at: http://masshealthpolicyforum.brandeis.edu/publications/pdfs/31-May07/MassHealthCareReformProgess%20Report.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2012.

- 31.Hecht J. Patrick-Murray Administration celebrates 98% health care coverage in Massachusetts. 2010. Available at: http://jonhecht.com/pressreleases/patrick-murray-administration-celebrates-98-health-care-coverage-massachusetts. Accessed December 8, 2012.

- 32.Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation of Harvard Law School. Massachusetts HIV/AIDS Resource Allocation Project. Available at: http://www.law.harvard.edu/academics/clinical/lsc/documents/Data_Needs_for_MA_HIV_Resource_Allocation_Project.pdf. Accessed November 12, 2012.

- 33.Holman J, Schneider K, Watson K, Muthur J, Flynn A. Massachusetts and Southern New Hampshire HIV/AIDS Consumer Study. 2011. Available at: http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/docs/dph/aids/consumer-study-june-2011.pdf. Accessed December 5, 2012.

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: syringe exchange programs—United States, 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(27):673–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez Aet al. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006–2009 PLoS ONE 201168)e17502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Massachusetts Department of Public Health Office of HIV/AIDS. The Massachusetts HIV/AIDS epidemic at a glance. Available at: http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/docs/dph/aids/2012-profiles/epidemic-glance.pdf. Accessed December 4, 2012.

- 37.Mayer K, Appelbaum J, Rogert T, Lo W, Bradford J, Boswell S. The evolution of the Fenway Community Health model. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(6):892–894. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. PR Newswire/Reuters. NHeLP and the AIDS Institute File HIV/AIDS discrimination complaint against Florida health insurers; advocates seek enforcement of ACA anti-discrimination provisions. 2014. Available at: http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/05/29/nhelp-aids-inst-file-idUSnPn3F6qSd+92+PRN20140529. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- 39.Greater than AIDS. FAQ: If I receive services from Ryan White or AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP), do I still need insurance? Available at: http://greaterthan.org/obamacare-faq/ryan-white-and-adap-if-i-receive-ryan-white-or-aids-drug-assistance-program-adap-do-i-still-need-insurance. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- 40.Communities Advocating Emergency AIDS Relief. CAEAR Coalition comments on the future of the Ryan White Program submitted to HHS. 2012. Available at: http://www.caear.org/downloads/CAEAR_Coalition_RW_Principles_7_31_2012.pdf. Accessed January 20, 2015.

- 41.HIV Health Reform. Treatment Access Expansion Project. 2012. Available at: http://www.HIVHealthReform.org/blog. Accessed September 9, 2014.

- 42. AIDS Watch. The Ryan White Program. A critical component for ending AIDS in America. April 28–29, 2014. Available at: http://www.aidsunited.org/data/files/Site_18/2014AidsUnited-FactSheet-RyanWhiteProgram.pdf. Accessed April 3, 2015.

- 43. AIDS Budget and Appropriations Coalition. FY2015 appropriations for federal HIV/AIDS programs. 2014. Available at: https://pwnusa.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/fy15-abac-chart-3-26-2014.pdf. Accessed January 20, 2015.

- 44.HRSA HIV/AIDS Bureau. The Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program: better with age. Available at: http://hab.hrsa.gov/livinghistory/issues/aging_8.htm. Accessed September 9, 2014.

- 45.Cahill S, Valadez R. Growing older with HIV/AIDS: new public health challenges. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(3):e7–e15. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaiser Family Foundation. 2009 survey of Americans on HIV/AIDS. Available at: http://www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/7890.cfm. Accessed September 12, 2012.

- 47.Anderson R, Fetner T. Cohort differences in tolerance of homosexuality: attitudinal change in Canada and the United States. Public Opin Q. 2008;72(2):311–330. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Inf Dis. 2011;52(6):793–800. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Supervie V, Garcia-Lerma J, Heneine W, Blower S. HIV, transmitted drug resistance, and the paradox of preexposure prophylaxis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(27):12381–12386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006061107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Supervie V, Barrett M, Kahn JS et al. Modeling dynamic interactions between pre-exposure prophylaxis interventions & treatment programs: predicting HIV transmission & resistance. Sci Rep. 2011;1:185. doi: 10.1038/srep00185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hallett TB, Baeten J, Heffron R et al. Optimal uses for antiretrovirals for prevention in HIV-1 serodiscordant heterosexual couples in South Africa; a modeling study. PLoS Med. 2011;8(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001123. e1001123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2015, March 6. Current Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions (map). Available at http://kff.org/health-reform/slide/current-status-of-the-medicaid-expansion-decision. Accessed March 23, 2015.

- 54. AIDS.gov. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Initiating antiretroviral therapy in treatment-naïve patients. 2014. Available at: http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/1/adult-and-adolescent-arv-guidelines/10/initiating-art-in-treatment-naïve-patients. Accessed May 13, 2014.

- 55.Hauschild B, Weddle A, Lubinski C, Tegelvik J, Miller V, Saag M. HIV clinical capacity and medical workforce challenges: results of a survey of Ryan White Part C-funded programs. Ann Forum Collab HIV Res. 2011;13(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 56.White House Office of National AIDS Policy. Improving outcomes: accelerating progress along the HIV care continuum. 2013. Available at: http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/onap_nhas_improving_outcomes_dec_2013.pdf. Accessed May 13, 2014.

- 57.Crowley J, Kates J. Updating the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program for a new era: key issues & questions for the future. 2013. Available at: http://kff.org/hivaids/report/updating-the-ryan-white-hivaids-program-for-a-new-era-key-issues-and-questions-for-the-future. Accessed October 30, 2014.