Abstract

College campus tobacco-free policies are an emerging trend. Between September 2013 and May 2014, we surveyed 1309 college students at 8 public 4-year institutions across California with a range of policies (smoke-free indoors only, designated outdoor smoking areas, smoke-free, and tobacco-free).

Stronger policies were associated with fewer students reporting exposure to secondhand smoke or seeing someone smoke on campus. On tobacco-free college campuses, fewer students smoked and reported intention to smoke on campus. Strong majorities of students supported outdoor smoking restrictions across all policy types.

Comprehensive tobacco-free policies are effective in reducing exposure to smoking and intention to smoke on campus.

Exposure to tobacco smoke harms nearly every organ of the body.1 Young adults smoke at rates higher than any other age group,2 likely in part because the tobacco industry aggressively markets to young adults3 as the youngest age group that they can legally target. Between 2001 and 2011, undergraduate enrollment increased 32% from 13.7 million to 18.1 million, with 42% of young adults (aged 18–24 years) attending a 2- or 4-year college or university. The National Center for Educational Statistics projects that this trend will continue, with a 13% increase in enrollment of students aged 24 years and younger from 2011 to 2021.4 Colleges are rapidly adopting a range of policies on tobacco, including tobacco-free policies that prohibit tobacco use on the entire grounds for students, faculty, staff, and visitors.

Smoke-free college campus policies have been associated with a drop in student smoking rates.5 On North Carolina college campuses, as tobacco policy strength increased (none, designated areas, or tobacco-free), less cigarette butt litter was found on the ground outside building entrances.6 As tobacco control advocates shift focus to promoting comprehensive tobacco-free policies, a more nuanced understanding of the benefits of these policies is necessary.

Previous research has indicated that college smoke-free policies lead to a reduction in student smoking rates,5 and strength of policy is linked to cigarette butt litter on college campuses.6 The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between the strength of the tobacco policy and exposure to secondhand smoke, seeing someone smoking, and intention to smoke on campus. We studied a range of policies on 8 public 4-year colleges and universities in California and found that the stronger the policy provisions, the lower the reported exposure to secondhand smoke, and seeing someone smoking. In addition, students on the tobacco-free campuses reported the lowest intention to smoke on campus in the next 6 months.

METHODS

Between September 2013 and May 2014, we surveyed students on 8 California 4-year college and university campuses with a range of policies (tobacco-free policy [n = 217], smoke-free policy [n = 230], designated outdoor smoking areas [n = 429], or California law [n = 217]). Tobacco-free policies prohibit all tobacco use on the entire grounds; smoke-free policies prohibit smoking on the entire grounds; campuses with designated outdoor areas have specific locations for smoking. Schools with no policy adhere to California state law, which prohibits smoking indoors and 20 feet from entrances on college campuses.7 In addition to variation in policy, we selected campuses from a variety of regions across the state to reflect social and political differences around California.

Students were recruited from high-traffic areas on campus and approached with the intercept method. Students filled out a 59-item written survey with questions on their exposure to secondhand smoke and individuals smoking, intentions to smoke on campus, and support for smoking restrictions.

We assessed student secondhand smoke exposure with the question, “In the past 7 days, I have been exposed to other people’s tobacco smoke on campus. (yes/no).” We assessed student exposure to individuals smoking on campus with the question, “In the past 7 days, I have seen someone smoking on campus. (yes/no).”

We assessed students’ intention to smoke on campus with the statement, “I intend to smoke a cigarette (even a puff) in the next 6 months on campus. (very likely, somewhat likely, somewhat unlikely, very unlikely).” We classified students responding “very likely” or “somewhat likely” as intending to smoke on campus. We assessed student support for outdoor smoking restrictions with the question, “Regulation of smoking in outdoor places is a good thing.” We combined responses of “strongly agree” or “agree” to indicate support of policy.

We compared responses to all 4 questions by policy type (California law, designated outdoor areas, smoke-free, and tobacco-free) by using the χ2 test.

RESULTS

We surveyed a total of 1309 students from 8 California campuses. The majority of respondents were women (61.3%) with no significant gender differences between campuses with different policies (Table 1). There were significant differences by ethnicity across policies (Table 1), with the tobacco-free campuses having more Asian students, and the campuses with designated outdoor areas having more Hispanic students.

TABLE 1—

Policy Impact on Tobacco Use and Perceptions of Policies Among Students at 8 Public 4-Year Colleges and Universities in California, 2013–2014

| Variable | Tobacco-Free, % (No.) | Smoke-Free, % (No.) | Designated Outdoor Areas, % (No.) | California Law Only, % (No.) | P |

| Demographic variables | |||||

| Race/ethnicity | <.01 | ||||

| White | 24 (51) | 36 (83) | 19 (81) | 28 (121) | |

| Black | 5 (11) | 5 (11) | 4 (19) | 4 (18) | |

| Asian | 32 (68) | 17 (39) | 21 (91) | 18 (78) | |

| Hispanic | 33 (70) | 37 (84) | 45 (192) | 39 (164) | |

| Other | 7 (15) | 6 (13) | 11 (45) | 11 (45) | |

| Female gender | 65 (141) | 62 (143) | 60 (258) | 60 (258) | .22 |

| Tobacco use | |||||

| Past 30 d smoking | 10 (21) | 11 (11) | 19 (81) | 12 (50) | .002 |

| I have seen someone smoking on campusa | 55 (119) | 68 (156) | 79 (337) | 95 (407) | <.01 |

| Exposed to secondhand smokeb | 38 (83) | 51 (117) | 68 (292) | 81 (349) | <.01 |

| Intend to smoke a cigarette (even a puff) in the next 6 mo on campusc | .02 | ||||

| Very or somewhat likely | 3 (6) | 9 (20) | 12 (51) | 9 (37) | |

| Very or somewhat unlikely | 97 (212) | 91 (209) | 88 (379) | 91 (393) | |

| Perceptions regarding tobacco policies | |||||

| Regulation of smoking on outdoor places is a good thingd | .04 | ||||

| Strongly agree or agree | 77 (167) | 67 (154) | 67 (289) | 71 (299) | |

| Neutral, disagree, or strongly disagree | 23 (49) | 33 (76) | 33 (141) | 30 (125) | |

Student exposure to individuals smoking on campus was assessed with the question, “In the past 7 days, I have seen someone smoking on campus. (yes/no).”

Student secondhand smoke exposure was assessed with the question, “In the past 7 days, I have been exposed to other people’s tobacco smoke on campus. (yes/no).”

Students’ intention to smoke on campus was assessed with the statement, “I intend to smoke a cigarette (even a puff) in the next 6 months on campus. (very likely, somewhat likely, somewhat unlikely, very unlikely).” Students responding “very likely” or “somewhat likely” were classified as intending to smoke on campus.

Student support was assessed with the question, “Regulation of smoking in outdoor places is a good thing. (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree).” Responses of “strongly agree” or “agree” were combined to indicate support of policy.

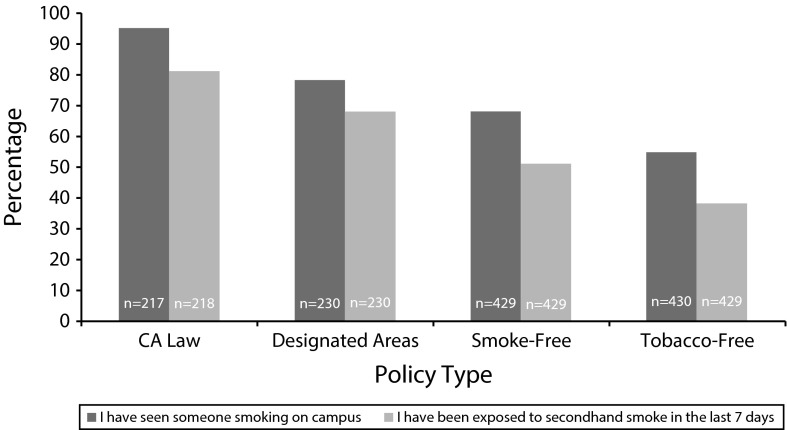

Past-30-day smoking was highest (19%) among students on campuses with designated outdoor smoking areas, compared to 10% to 12% on campuses with the other policies (P = .002). As policy strength increased, fewer individuals reported exposure to secondhand smoke (dropping from 81% to 38%) and observing a smoker on campus (dropping from 95% to 55%; Figure 1). Only 3% of students on the tobacco-free campuses reported an intention to smoke in the next 6 months on campus, compared with 9% to 12% on campuses with less comprehensive policies. Approval for outdoor policies was highest among students from schools with tobacco-free policies (77%), but there was high approval across policy types (67%–70%).

FIGURE 1—

Observations of individuals smoking and exposure to second-hand smoke among students: public 4-year colleges and universities, California, 2013–2014.

Note. P < .01. As the strength of tobacco policy increased, exposure to secondhand smoke and observation of individuals smoking significantly decreased.

DISCUSSION

Our results show high compliance with campus tobacco policies, with more comprehensive policies (including tobacco-free grounds) having significantly larger effects on protecting students from exposure to smoking and secondhand smoke and lower intention to smoke on campus. Although the clean indoor air movement began across the country in the 1970s,8 outdoor tobacco-free policies were still an emerging trend in 2014 and there are few studies showing the efficacy of such policies on college campuses.

There are currently debates on many college campuses about whether to go tobacco-free, as well as which policy to enact (designated outdoor smoking areas, smoke-free, or tobacco-free). Results of this study support the findings of Lee et al., who demonstrated that campuses with comprehensive tobacco-free policies were associated with less cigarette butt litter, a proxy for cigarette smoking on campus.6 Taken together, the results of this study and existing literature5,6 support the efficacy of tobacco-free policies on college campuses in reducing exposure to secondhand smoke and smoking intent.

Limitations

This study includes a small sample size limited to 8 California public college and university campuses, and the sample was not randomly selected. California has a longstanding tobacco control program and low smoking rates.9 It is possible that differences noted could be attributed to factors other than tobacco policy.

All the University of California campuses were tobacco-free, whereas the campuses with the less-restrictive policies were California State University campuses. Differences in smoking rates between students in the University of California versus California State University campuses could contribute to differences in observation and exposure to smoking. To test this, we assessed differences in past-30-day smoking rates between University of California and California State University campuses and found no significant difference (10% vs 14%, respectively; P = .08).

This study should be replicated with a larger sample on a national scale to ensure that these results do not depend on the specific policy environment in California or socioeconomic or demographic differences between university systems.

Conclusions

Campus tobacco policies are working in California, with high compliance, less secondhand smoke exposure, and lower intentions to smoke on campus. With each successively stronger tobacco policy, fewer students report exposure to secondhand smoke and having seen a person on campus smoking. Fewer students on tobacco-free campuses report an intention to smoke in the next 6 months on campus. Strong majorities of students support outdoor smoking regulation. Colleges should adopt comprehensive tobacco-free policies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (grants CA-061021 and CA-113710) and University of California Tobacco Related Disease Research Program (grant 22FT-0069).

Note: The funding agencies played no role in the conduct of the research or preparation of the article.

Human Participant Protection

Human participants approval was obtained from the University of California San Francisco Committee on Human Research.

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ling PM, Glantz S. Why and how the tobacco industry sells cigarettes to young adults: evidence from industry documents. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(6):908–916. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Center for Education Statistics. Fast facts: enrollment. Available at: http://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=98. Accessed October 20, 2014.

- 5.Seo D-C, Macy JT, Torabi MR, Middlestadt SE. The effect of a smoke-free campus policy on college students’ smoking behaviors and attitudes. Prev Med. 2011;53(4-5):347–352. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee J, Ramney L, Goldstein A. Cigarette butts near building entrances: what is the impact of smoke-free college campus policies? Tob Control. 2013;22:107–112. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. California Assembly Bill No. 846. Available at: http://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/tobacco/Documents/CTCPAb-846-342-chaptered.pdf. Accessed October 20, 2014.

- 8.Eriksen MP, Cerak RL. The diffusion and impact of clean indoor air laws. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:171–185. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lightwood J, Glantz SA. The effect of the California tobacco control program on smoking prevalence, cigarette consumption, and healthcare costs: 1989–2008. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2):e47145. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]