Abstract

Introduction

People living with and beyond cancer are vulnerable to a number of physical, functional and psychological issues. Undertaking a holistic needs assessment (HNA) is one way to support a structured discussion of patients’ needs within a clinical consultation. However, there is little evidence on how HNA impacts on the dynamics of the clinical consultation. This study aims to establish (1) how HNA affects the type of conversation that goes on during a clinical consultation and (2) how these putative changes impact on shared decision-making and self-efficacy.

Methods and analysis

The study is hosted by 10 outpatient oncology clinics in the West of Scotland and South West England. Participants are patients with a diagnosis of head and neck, breast, urological, gynaecological and colorectal cancer who have received treatment for their cancer. Patients are randomised to an intervention or control group. The control group entails standard care—routine consultation between the patient and clinician. In the intervention group, the patient completes a holistic needs assessment prior to consultation. The completed assessment is then given to the clinician where it informs a discussion based on the patient's needs and concerns as identified by them. The primary outcome measure is patient participation, as determined by dialogue ratio (DR) and preponderance of initiative (PI) within the consultation. The secondary outcome measures are shared decision-making and self-efficacy. It is hypothesised that HNA will be associated with greater patient participation within the consultation, and that shared decision-making and feelings of self-efficacy will increase as a function of the intervention.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been given a favourable opinion by the West of Scotland Research Ethics Committee and NHS Research & Development. Study findings will be disseminated through peer-reviewed publications and conference attendance.

Trail registration number

Clinical Trials.gov NCT02274701.

Keywords: ONCOLOGY, SOCIAL MEDICINE, MENTAL HEALTH, MEDICAL EDUCATION & TRAINING, STATISTICS & RESEARCH METHODS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first randomised controlled trial to examine the impact of holistic needs assessment (HNA) on the dynamics of conversation and any subsequent impact on shared decision-making and self-efficacy.

We are only collecting data from one consultation per patient. However, it is recommended that HNA should be administered across the patient pathway (at diagnosis, pretreatment, and then post-treatment). Therefore, we are unable to comment on the impact of HNA on the patient–clinician dynamic over time.

Applying a holistic approach to patient care has many benefits, but only around 25% of cancer survivors in the UK receive a HNA and care plan. Gaining a greater insight into the delivery and experience of HNA in the clinical environment will support evidence-based implementation of HNA in the UK and internationally.

Introduction

Background and rationale

There is currently a concerted political, ethical and philosophical push towards improving patient experience and care in the UK National Health Service.1 2 Government initiatives such as ‘Better Cancer Care: An Action Plan’,3 and policy guidelines such as ‘Improving supportive and palliative care for adults with cancer’4 address the need to improve satisfaction, reduce distress, offer support and save money by facilitating self-care. Improved collaboration between patient and clinician is central to this agenda.5 However, it is not clear how collaboration is optimised, who should be sharing what decisions, or how this may or may not impact on outcomes.6 Therefore, evidence grounded in the systematic analysis of the process and impact of collaboration is rare as well as important.

Communication in cancer care is a well-researched field. Effective communication between the health professional and the patient is associated with improved psychological functioning of the patient,7 8 adherence to treatment and pain control,9 and higher quality of life and satisfaction.10 By contrast, it has been suggested11 that poor communication may have a number of negative effects on the patient and the treatment process, including the nature and quality of information transmission, decision-making, and the psychosocial experience of the patient.

There are inherent methodological and philosophical challenges attached to this line of enquiry. Most notably the idea of ‘poor’ or ‘effective’ communication is subjective, with factors such as patient behaviour, time, resources and previous training all affecting clinician communication style.12 The aim of the current study is to understand more about the factors that may impact on the quality of communication within the clinical consultation.

The intervention in this study is holistic needs assessment (HNA). HNA is a checklist completed by the patient prior to consultation. It signposts issues of emotional, practical, financial and clinical concern. The purpose of HNA is to identify a patient's individual needs in order to facilitate better collaboration.13 During consultation, the HNA facilitates a dialogue that will have the patient's concerns at the centre. In conjunction with a subsequent care plan, the process supports timely intervention based on a collaborative, person-centred discussion.13

In order to gather pertinent data, we are going to audio record clinical consultations. We recognise that this action may have an impact in itself, potentially changing the subtle dynamics of the consultation we intend to study. Nevertheless, this is the same for both arms of the study and a valuable method of analysis.14 Through detailed examination of communication patterns within the consultation, we intend to ascertain if and how a structured conversation derived from personally identified patient needs impacts on subsequent outcomes. To the best of our knowledge this is the first randomised controlled trial to examine the impact of HNA on patient–clinician communication, and the subsequent impact on shared decision-making and patient-reported self-efficacy.

Objectives

The objectives are to examine

The impact of HNA on consultation style;

The impact of HNA on shared decision-making;

The impact of HNA on patient-reported self-efficacy.

In order to meet these objectives, the study will test the following hypotheses:

Use of HNA within clinical consultation will facilitate increased levels of patient participation.

Use of HNA within clinical consultation will facilitate increased levels of shared decision-making.

Use of HNA within clinical consultation will facilitate increased feelings of self-efficacy.

Method

Study design and setting

This protocol follows SPIRIT15 2013 guidelines.

It is a randomised controlled trial. The randomisation pertains to the patients within each clinic. Data collection will occur within a post-treatment, outpatient cancer clinic. Ten clinics from the West of Scotland and South West England will participate. The clinics care for patients with head and neck, breast, urological, gynaecological and colorectal cancer.

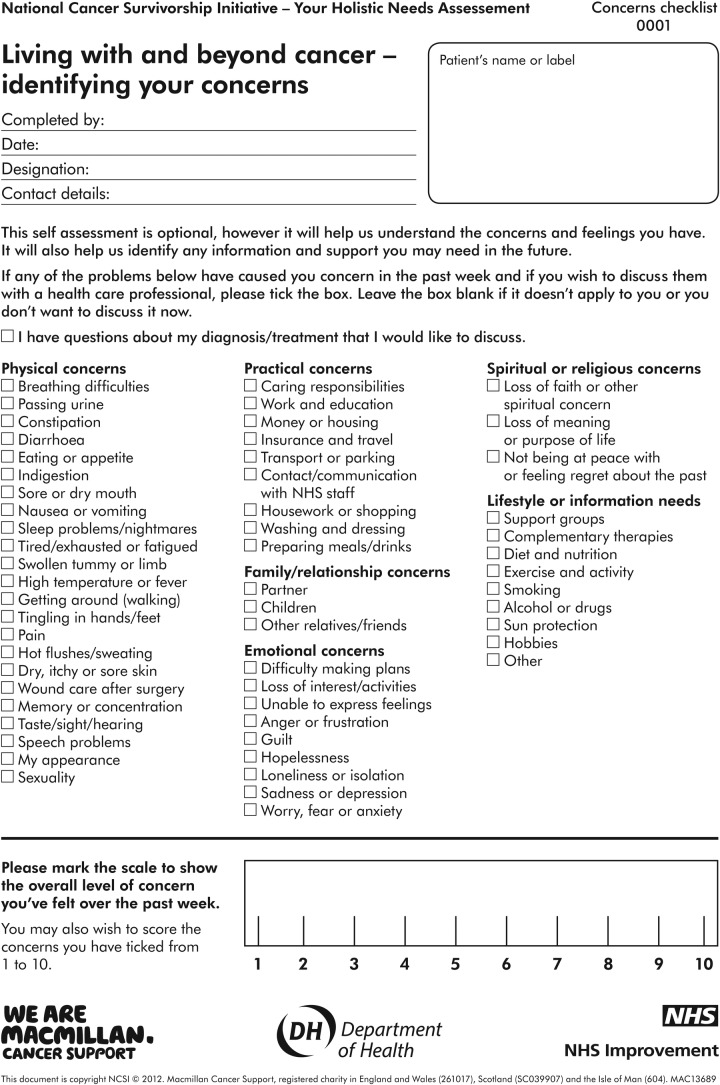

Prior to consultation, the patient will complete a demographic questionnaire. Those in the intervention group will then complete a holistic needs assessment titled the ‘Concerns Checklist’ (figure 1). Within the control group there will be no additional intervention, care will continue as normal. Within both groups, the consultation will be audio recorded.

Figure 1.

The concerns checklist.

Post-consultation, the patient will complete two secondary outcome measures; CollaboRATE5 and The Lorig Self-efficacy scale.16 CollaboRATE measures patient perception of shared decision-making. One of the strengths of CollaboRATE is the ability to complete it in less than 30 s. The Lorig self-efficacy scale is the optimal measure for self-reported self-efficacy in chronic disease management according to Davies.17

Analysis of the audio recordings will be conducted by MEDICODE.18 The MEDICODE system ascertains the type of participation occurring within the consultation according to two main measures: dialogue ratio (DR) and preponderance of initiative (PI). DR is assessed by coding how much of the consultation is discussion and how much is instruction. PI is assessed by recording which participant initiates aspects of conversation within the consultation. These two measures (DR and PI) together give a summary score of who is talking, what about, and for how long. These measures can then be analysed alongside the secondary outcome measures.

Eligibility criteria

The study sample will be composed of patients over the age of 18. Eligible patients have undergone treatment for their diagnosis and are attending a post-treatment clinic. Exclusion criteria includes those deemed incapable of consenting to participate as defined by the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act (2000), and any reason which in the opinion of the clinician/investigator interferes with the ability of the patient to participate in the study. A sample of 156 patients will be recruited. The clinicians who deliver and assist with the clinics (n=16) span four professional groups: consultant oncologist, cancer nurse specialist, radiographer and surgeon.

Intervention

All participating clinicians will attend a training session in the use of HNA to enhance standardisation and concordance with the protocol. The training will be delivered by the study consultant psychologist (EM) and will last for 2 h. It will involve a variety of teaching methods including presentation slides, interactive exercises and finishes with a DVD that provides an example of a patient and clinician using the HNA together. There will also be an opportunity for the clinicians to complete the HNA themselves. The aim is to equip the clinicians with the skills and confidence to respond to the patient's needs and concerns as identified through the assessment. These responses may range from simply listening to the patient to referring the patient to a member of the wider team, such as a clinical psychologist, a chaplain, for financial advice or social work.

Individuals in the intervention group will be given the HNA (Concerns Checklist: figure 1) to complete before consultation. Each clinic has identified a quiet area where the researcher can sit with the patient, talk through the form and then leave them to complete it. They will be asked to hand it to their clinician when they enter the consultation room. Any actions taken by the patient or clinician will be recorded in a care plan. A copy of the care plan will stay in patient notes, the patient will keep a copy and a copy will be sent to any other members of the multidisciplinary team who are involved in the patient's care.

If at any point during this process the patient decides to withdraw, they will be free to do so without question. All patients will be informed that withdrawing from the study will not impact the care they receive in any way.

Outcomes

Sociodemographic data: sex, age, postcode, ethnicity, relationship status and education.

Clinical data: cancer type and stage and form of treatment received.

Clinician data: gender, profession and years of experience.

Data will also be obtained on who is present in the consultation room. For example, the patient may bring a family member with them.

This will allow the research team to examine what, if any impact variables such as sex, age, ethnicity, support network, and education have on the research aims. Previous literature corroborates the influence of these variables on distress within patients with cancer.19–21

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure is patient participation as measured by DR and PI using the conversational coding software ‘MEDICODE’.22 PI measures the extent to which conversations are started by the clinician or the patient. The whole consultation is then summarised by this measure according to who begins most of the conversation. It generates an overall score of −1 (all clinician) to +1 (all patient). DR measures the extent to which the whole consultation consists of monologues, dyads and discussions. It generates an overall score of 0 (monologue) to 1 (dialogue). The output is a graphical representation of these two summary measures.

MEDICODE was constructed to measure conversations about medicine management23 and has not been used previously to analyse cancer consultations. However, the principles of DR and PI are transferable to any clinical consultation, and were chosen for this study as the best way of capturing the subtle shifts in conversation hypothesised to occur.

Secondary outcome measures

Shared decision-making as measured by the CollaboRATE scale5

CollaboRATE is a survey-based validated tool24 designed to create a fast way to measure how much effort clinicians make to explain their patients’ health issues; how much effort they make to listen to the issues that matter most to their patients, and how much effort they make to integrate the patients’ views and health beliefs.

Self-efficacy as measured by the Lorig self-efficacy scale

The Lorig Self-Efficacy for Managing Chronic Disease 6-Item Scale post-consultation encompasses several domains common to many chronic diseases including symptom control, role function, emotional functioning and communicating with physicians. The scale has good internal consistency and construct validity.17 25 It is free and easy to use, and it has been extensively used at both clinical and research levels within this patient population.26 27 We acknowledge that a limitation of the tool is that it has not been widely used with all cancer types. However, it appears to be the best generic tool for this purpose.17

Sample size calculation

To achieve statistical significance, 78 patients are needed in the experimental and 78 in the control groups. The power calculation was done on G*Power 3.28 It is based on the following assumptions.

The standard setting of α was adjusted from 0.05 to 0.0125 to account for the four primary end points (DR, PI, CollaboRATE and Lorig).29 Power of 0.8 was assumed as sufficient to claim a difference between groups as a consequence of the intervention. The anticipated effect size of d=0.5 is an estimate. There are no data on the specific effects of the holistic needs assessment technique proposed here. The value of d=0.5 was arrived at by aggregating the reported effect sizes of other comparable psychological interventions targeted at improving psychological well-being in the cancer population.30 31 Reported effect sizes range from negligible (d=0.33 in older meta-analyses of interventions to reduce anxiety in patients with cancer) to large effects (d=0.77) claimed in some recent trials.31 Sheard and McGuire also noted that the higher quality trials tended to produce much higher effect sizes than those of lower quality (0.63 vs 0.24). Given that this study proposal meets their quality criteria for a high-quality trial (randomised and >40 sample size), 0.5 can be considered a coherent and conservative effect size estimate.

Recruitment

While we plan to standardise recruitment as far as possible by selecting patients at the same point in their treatment journey, we need to account for the different pathways operating in the clinics. To this end, there are two recruitment strategies.

Following treatment, the patient will spend time in hospital. A member of the clinical care team will approach the patient and introduce the study. If the patient expresses an initial interest the clinician will give the patient a study pack. This will contain a welcome letter, a participant information sheet and a consent form.

OR

During treatment, the patient will attend the clinic. The clinician will introduce the study to the patient at one of their scheduled appointments and hand over a study pack.

Contact with patients will be done in person where possible. However, in exceptional circumstances, if the clinician has not made personal contact with the patient, the hospital will write to the patient on behalf of the research team and invite them to participate. The letter will be sent in a plain envelope to protect the patient’s privacy.

Randomisation

Blocked randomisation will be carried out by the research team, using a computer-generated sequence to ensure an almost equal number of patients within each group. Stratified randomisation will be used to ensure that patient groups are similar with respect to prognostic factors such as age and sex. Patients will provide written informed consent to participate before they are informed as to which group (intervention or control) they will be in. This is to avoid potential bias from patients who may request to be in a certain group. The randomisation sequence will be managed by the research assistant using sealed envelopes. The coders who analyse the audio recordings will be blind to the allocation of patients to the intervention or control group.

Data collection, management and analysis

There will be a 2-week pilot. This is to test the study protocol in practice and enable the construction of an optimal coding framework for MEDICODE. It is our intention to structure the coding framework around the theory of holistic needs assessment, coding elements of the clinical conversation according to the concern discussed: Physical, Practical, Family/relationship, Emotional, Spiritual and Lifestyle (see figure 1). This period will allow for the testing of such a coding framework. Changes to the protocol and coding framework will be made accordingly.

The pilot will also allow time for broader reflection. The research team will ask the clinicians to review their training, the patients’ response to the HNA, time and ease to complete the HNA, and how their service is managing any referrals. If the pilot uncovers any deficiencies in the design this can be reviewed with the team and addressed.

Following this phase, the process is as follows. The researcher will meet the patient in the waiting area of the clinic. The researcher will summarise the study process again, ensure the patient is happy to continue, collect their consent form, and then ask them to complete a demographic questionnaire. While the patient is completing their demographic form, the researcher will randomise the participant into an intervention or control group. Individuals in the intervention group will be given the HNA (Concerns Checklist figure 1) to complete. At this stage, the patient will also have the opportunity to add their contact details should they wish to take part in future follow-up interviews to discuss their experiences of HNA (or not) and subsequent use of support services.

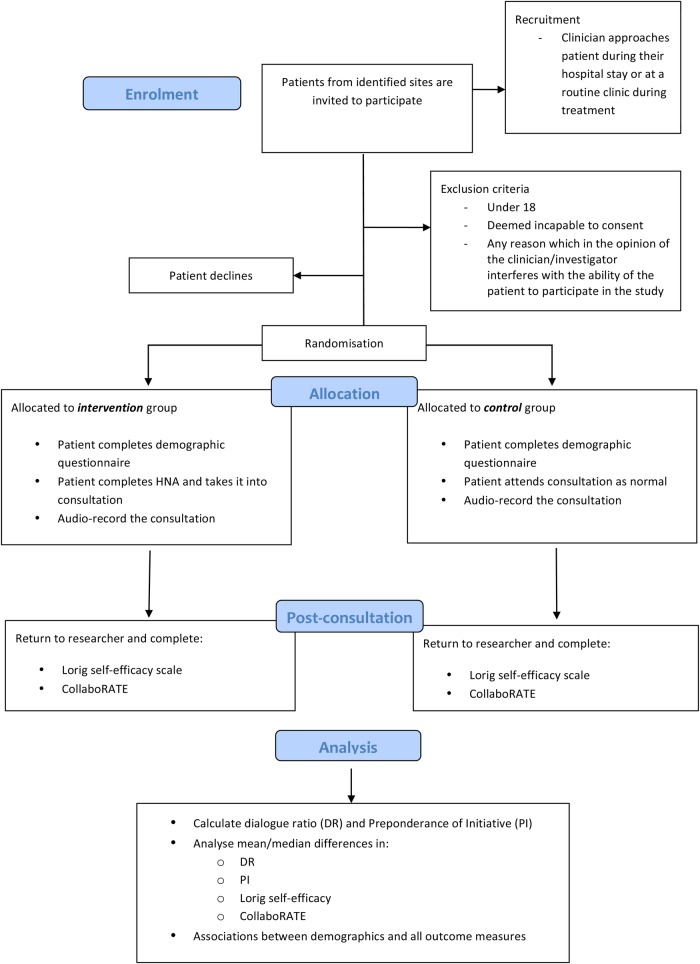

When the patient is called, the researcher will accompany them to the consultation room and start the recording device. The researcher will then leave the consultation room. The clinician will stop the recording device at the end of the consultation. All patients (in both groups) will return to the researcher, post-consultation, and complete the Lorig self-efficacy scale and CollaboRATE (figure 2). Data collection will run for 12 months.

Figure 2.

The study flow.

Data management

Research data and patient-related information will be managed in accordance with relevant regulatory approvals.

Data analysis

The following statistical methods will be used for analysing the data.

Use of HNA within clinical consultation will facilitate increased levels of patient participation

Patient participation within the consultation will be measured by the two MEDICODE measures: PI and DR. The data will first be tested for outliers using box plots, and for normality using a combination of PP, QQ plots and Shapiro-Wilk test. If normality is found, homogeneity of variance between groups will be tested with Levene's test. Subsequent calculations will be based on the outcomes of these assumption tests. If normality and homogeneity of variance are established, mean PI and DR will be compared between the intervention and control group using a t test. If normality and/or homogeneity of variance cannot be established, a corresponding non-parametric method will be employed.

Use of HNA within clinical consultation will facilitate increased levels of shared decision-making

Shared decision-making will be measured with CollaboRATE. As shown above, the data will be tested for outliers, normality and homogeneity of variance. If normality and homogeneity of variance are established, mean collaboRATE scores will be compared between the intervention and control groups using a t test; if not, a corresponding non-parametric method will be employed.

Use of HNA within clinical consultation will facilitate increased feelings of self-efficacy

Self-efficacy will be measured with the Lorig self-efficacy scale. As shown above, the data will be tested for outliers, normality and homogeneity of variance. If normality and homogeneity of variance are established, mean Lorig scores will be compared between the intervention and control groups using a t test; if not, a corresponding non-parametric method will be employed.

Methods for any additional analyses

Additionally, exploratory analyses will be carried out on various associations. For example, associations will be tested between the outcome variables and demographic data. We will also test for any potential associations between DR and/or PI with CollaboRATE and Lorig self-efficacy across the whole sample. The purpose of this is to ascertain any potential relationships between these measures regardless of study group. For example, it seems intuitive that people who are demonstrably more involved in their consultations as evidenced by high patient PI and DR scores would be more likely to score highly for self-efficacy and collaboration regardless of study group.

We also plan to conduct subgroup analyses according to characteristics of the clinicians. For example, we have information on gender, profession and years of experience. These can be used to explore any potential trends in greater depth.

It is acknowledged that a disadvantage of randomising by patient is that the clinician will carry out consultations with patients who are in the intervention and control groups. Therefore, ‘learning’ from the consultations where an HNA is applied may cross over into their interactions with the control group. This would not impact on clinician ability to identify needs personal to the patient as the patient would not have thought about this in the same manner as those completing an HNA. Nevertheless, this ‘learning’ could potentially contaminate the effect on communication between the groups. However, since the time when HNA will be introduced into their consultations is known, we can use this information to investigate whether there is a trend in communication efficacy through time. Fitting a trend line to the full data set can do this. ‘Time’ can then be used as a covariate in the analysis to remove any confounding effect of ‘learning’.

Missing data

Cases will be excluded list-wise by default.32

Discussion

Applying a holistic approach to patient care has many benefits.13 33 Yet, only around 25% of cancer survivors in the UK receive a holistic needs assessment and care plan.13 We therefore wish to gain a greater insight into the delivery and experience of HNA in the clinical environment. The aim is to support evidence-based implementation of HNA in the UK.

The role of communication on patient outcome has received considerable attention in the field of cancer care. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, there are no published randomised controlled trials that focus on the patterns of communication between the patient and clinician when a holistic needs assessment is used or not. This study has a unique focus on the relationship between communication style, shared decision-making and self-efficacy. Traditionally, in the UK, medical consultations are led by the clinician, but there is evidence that collaboration can be facilitated by training the clinicians in person-centred care.34 What we do not know is whether this can also be achieved by prioritising patients’ needs through the use of HNA. Further, we do not know whether this leads to improved feelings of self-efficacy and a sense of shared decision-making.

Perception of self-efficacy is particularly important, as it is a critical feature of chronic disease management and can predict the success of self-management programmes among patients.35 36 Findings from this study may pave the way for exploring the impact of HNA over time. For example, longitudinal follow-up could ascertain whether there is any association between self-efficacy, self-management and the patient's subsequent use of the health service.

There are limitations to the study. As discussed above, there is a risk of crossover learning from the experimental to the control. We could have mitigated this using a cluster-randomised trial design, but this was not an option due to the increased number of participants required. Further, while crossover learning is a risk, we do not consider it will undermine the key objectives as the main intervention is the concerns checklist, not the skills of the clinician.

Guidance suggests that HNA should be delivered across the patient pathway, not just at the post-treatment stage. We selected the post-treatment stage only to accommodate anticipated difficulties around ensuring the patient sees the same clinician throughout. In practice, this is not always the case which would confound our results in this randomised controlled trial. There were also pragmatic reasons. Practically, the clinics felt most able to support this study at the post-treatment stage. This is because at this stage there would be no need for any radical changes to clinical practice. This was considered paramount, as should we find any favourable results they are more likely to be transferable to routine practice in future.

Ethics and dissemination plans

This study was given a favourable opinion by the West of Scotland Research Ethics Committee (14/WS/0126) on 3 June 2014. NHS Research & Development approval followed on 26 August 2014. This study was also approved by the Clinical Trials Executive Committee within the Beatson West of Scotland Cancer Centre on 13 June 2014.

Recruitment began in January 2015, and completion will occur on reaching the necessary sample size within each group. It is predicted to take 12 months to reach completion. It is recognised that as the patient’s symptoms fluctuate, so may their capacity to consent. Consent will be assessed by the clinician on the day of the study. Patients without capacity to consent will be excluded from data collection.

The dissemination of the findings will be predominately carried out through publications in peer-reviewed journals and attendance at national and international conferences. Additionally, this body of work will be promoted by the funders of the study, Macmillan Cancer Support UK.

Footnotes

Contributors: AS, JY, CW, CR, M-TL and EM devised the study protocol and are all members of the steering group for this research. AS drafted the manuscript. JY oversees the day-to-day organisation of the study, drafted the manuscript and is a member of the steering group. EMcA provided guidance on statistical analysis. DS, SS, DW, JM and ER drafted the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Macmillan Cancer Support UK.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: West of Scotland Research Ethics Committee 14/WS/0126 IRAS ref: 114947. R&D Approval-GN14ON242.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Coulter A, Collins A. Making shared decision making a reality. No decision about me, without me. London: The King's Fund, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Scottish Government. The Quality Strategy 2010. http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/Health/NHS-Scotland/NHSQuality/QualityStrategy

- 3.Scottish Executive. Better cancer care: an action plan. Edinburgh: Scottish Government, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Improving supportive and palliative care for adults with cancer 2004. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/csgsp

- 5.Elwyn G, Barr PJ, Grande SW et al. . Developing CollaboRATE: a fast and frugal patient-reported measure of shared decision making in clinical encounters. Patient Educ Couns 2013;93:102–7. 10.1016/j.pec.2013.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cribb A. Involvement, shared decision-making and medicines. London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCormack LA, Treiman K, Rupert D et al. . Measuring patient-centered communication in cancer care: a literature review and the development of a systematic approach. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:1085–95. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ford S, Fallowfield L, Lewis S. Doctor-patient interactions in oncology. Soc Sci Med 1996;42:1511–19. 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00265-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown JE, Brown RF, Miller RM et al. . Testing health care professionals’ communication skills: the usefulness of highly emotional standardized role-playing sessions with simulators. Psychooncology 2000;9:293–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fukui S, Ogawa K, Yamagishi A. Effectiveness of communication skills training of nurses on the quality of life and satisfaction with healthcare professionals among newly diagnosed cancer patients: a preliminary study. Psychooncology 2011;20:1285–91. 10.1002/pon.1840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thorne S, Bultz BD, Baile WF. Is there a cost to poor communication in cancer care?: a review of the literature. Psychooncology 2005;14:875–84. 10.1002/pon.947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fagerlind H, Kettis Å, Glimelius B et al. . Barriers against psychosocial communication: oncologists’ perceptions. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3815–22. 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.1609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snowden A, White C. Assessment and care planning for cancer survivors: a concise evidence review. Macmillan Cancer Support, 2014. http://be.macmillan.org.uk/be/p-21255-assessment-and-care-planning-for-cancer-survivors-a-concise-evidence-review.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elwyn G. Patients’ recordings of consultations are a valuable addition to the medical evidence base 2014;2078:10–11. 10.1136/bmj.g2078 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG et al. . SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Ritter PL et al. . Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Eff Clin Pract ECP 2001;4:256–62. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11769298 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davies N. Self-management programmes for cancer survivors: a structured review of outcome measures. 2009. http://www.ncsi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Outcome-Measures-for-Evaluating-Cancer-Aftercare.pdf

- 18.Richard C, Lussier MT. MEDICODE: an instrument to describe and evaluate exchanges on medications that occur during medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns 2006;64:197–206. 10.1016/j.pec.2006.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mertz BG, Bistrup PE, Johansen C et al. . Psychological distress among women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2012;16:439–43. 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waller A, Williams A, Groff SL et al. . Screening for distress, the sixth vital sign: examining self-referral in people with cancer over a one-year period. Psychooncology 2013;22:388–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agarwal J, Powers K, Pappas L et al. . Correlates of elevated distress thermometer scores in breast cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:2125–36. 10.1007/s00520-013-1773-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richard C, Lussier MT. Measuring patient and physician participation in exchanges on medications: dialogue ratio, preponderance of initiative, and dialogical roles. Patient Educ Couns 2007;65:329–41. 10.1016/j.pec.2006.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lussier MT, Richard C, Guirguis L et al. . MEDICODE A comprehensive coding method to describe content and dialogue in medication discussions in healthcare provider-patient encounters: Perspectives from Medicine, Nursing and Pharmacy. International Conference on Communication in Healthcare; Montreal, Canada 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barr PJ, Thompson R, Walsh T et al. . The psychometric properties of CollaboRATE: a fast and frugal patient-reported measure of the shared decision-making process. J Med Internet Res 2014;16:e2 http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3906697&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract 10.2196/jmir.3085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorig K, Stewart A, Ritter P. Outcome measures for health education and other health care interventions. London: Sage Publications, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nielsen BK, Mehlsen M, Jensen AB et al. . Cancer-related self-efficacy following a consultation with an oncologist. Psychooncology 2013;22:2095–101. 10.1002/pon.3261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mystakidou K, Tsilika E, Parpa E et al. . Relationship of general self-efficacy with anxiety, symptom severity and quality of life in cancer patients before and after radiotherapy treatment. Psychooncology 2013;22:1089–95. 10.1002/pon.3106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG et al. . G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007;39:175–91. 10.3758/BF03193146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cabin RJ, Mitchell RJ. To Bonferroni or not to Bonferroni: when and how are the questions. Bull Ecol Soc Am 2000;81:246–8. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20168454 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheard T, Maguire P. The effect of psychological Interventions on anxiety and depression in cancer patients. Results of two meta-analyses. Br J Cancer 1999;80:1770–80. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schou I, Ekeberg O, Karesen R et al. . Psychosocial intervention as a component of routine breast cancer care who participates and does it help? Psychooncology 2008;17:716–20. 10.1002/pon.1264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Field A. Discovering statistics using SPSS. 2nd edn London: Sage Publications Ltd, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brennan J, Gingell P, Brant H et al. . Refinement of the distress management problem list as the basis for a holistic therapeutic conversation among UK patients with cancer. Psychooncology 2012;21:1346–56. 10.1002/pon.2045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Latter S, Sibley A, Skinner TC et al. . The impact of an intervention for nurse prescribers on consultations to promote patient medicine-taking in diabetes: a mixed methods study. Int J Nurs Stud 2010;47:1126–38. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verevkina N, Shi Y, Fuentes-Caceres VA et al. . Attrition in chronic disease self-management programs and self-efficacy at enrollment. Heal Educ Behav 2014;41:590–8. 10.1177/1090198114529590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farrell K, Wicks MN, Martin JC. Chronic disease self-management improved with enhanced self-efficacy. Clin Nurs Res 2004;13:289–308. 10.1177/1054773804267878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]