Abstract

This correspondence concerns a recent publication in Cancer Cell by Liu et al. 1 who analyzed a long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) that they designated “ NKILA”. Liu et al. found that NKILA (1) is upregulated by immunostimulants, (2) has a promoter with an NF-ĸB binding motif, (3) can bind to the p65 protein of the NF-ĸB transcription factor and then interfere with phosphorylation of IĸBα, and (4) negatively affects functions that involve NF-ĸB pathways. And, importantly, they found that (5) low NKILA expression in breast cancers is associated with poor patient prognosis. However, they entirely failed to mention PMEPA1, a gene which runs antisense to NKILA, and the expression of which is associated with several tumors and which encodes a protein that participates in immune pathways.

The PMEPA1 locus, including its promoter region, which Liu et al. 1 only discuss in regard to NKILA, is highly conserved through evolution. Our impression is that NKILA emerged only later in evolution, possibly as an additional means of PMEPA1 regulation. Liu et al., however, only consider direct binding between NKILA and NF-ĸB as the mechanism for their in vivo observations of NKILA function, but do not provide solid evidence for their model. If in vivo observations by Liu et al. could be explained by NKILA regulation of PMEPA1, it would contribute to the establishment of PMEPA1 as an important topic of cancer research. We feel that the herein presented discussion is necessary for a correct interpretation of the Liu et al. article.

Keywords: Breast cancer, NKILA, PMEPA1, NF-ĸB, long noncoding RNA, antisense, promoter, evolution

Correspondence

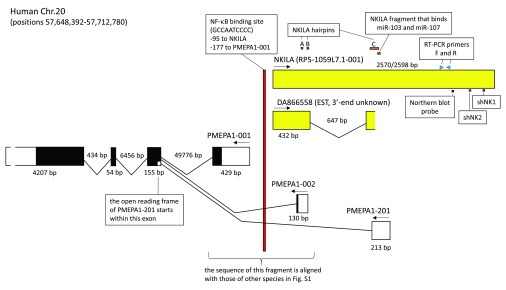

Liu et al. 1 investigated breast cancer cell lines for possible association of known long noncoding transcripts with immunostimulation. They found that an unspliced lncRNA, which they designated “ NKILA” (represented by large yellow box in Figure 1), could be upregulated by several immune agents. However, they did not mention the existence of a reported spliced form of NKILA (GenBank accession DA866558, see Figure 1), or, - our major criticism - that NKILA is divergently transcribed from prostate transmembrane protein, androgen induced 1 ( PMEPA1) and antisense to some of its transcripts (see Figure 1). One of the alternative names for PMEPA1 is solid tumor associated gene 1 ( STAG1) 2, and its expression was found upregulated in several tumors including breast cancer (e.g., references 2 and 3). Liu et al. 1 found that the NKILA promoter region contains an NF-κB binding motif ( Figure 1), which according to our analysis is rather well conserved among eutherian mammals ( Supplementary file S1). However, whereas the PMEPA1-001 transcript open reading frame and a part of the intergenic promoter region are highly conserved through evolution, this seems to be true to a lesser degree for NKILA equivalent transcripts ( Supplementary file S1 and discussion therein). So, from the standpoint of evolution, a logical hypothesis for the function of the seemingly younger NKILA is its possible interference with PMEPA1 expression 4, 5.

Figure 1. Schematic view of the PMEPA1 plus NKILA region of human Chr. 20.

The figure summarizes several data from the study by Liu et al. for NKILA and its promoter, while also showing overlapping transcripts that were neglected in that study. The NKILA transcript identified by Liu et al. roughly corresponds with transcript RP5-1059L7.1-001 as summarized in the GRCh38.p2 dataset of the Ensembl database ( http://www.ensembl.org/index.html). GenBank accession DA866558 (RP5-1059L7.1-002 in Ensembl) contains an expressed sequence tag (EST) which represents the 5’ end of a spliced transcript and for which the 3’ end is not known. The depicted summary of the PMEAP1 transcripts -001, -002 and -201, is derived from the Ensembl database and agrees with GenBank reports; for additional variations of PMEAP1 transcripts we refer to the Ensembl database. Exons are indicated by boxes, with protein coding regions in black. The 3’ UTR of PMEPA1 is not drawn in correct proportion to the other exon regions. Arrows indicate the direction of transcription, and genomic regions are measured in basepairs. The figure also shows from the Liu et al. report the positions of the NF-κB binding promoter element, the NKILA hairpin-prone regions, the NKILA region that binds miR-103 and -107, the NKILA binding sites for the Northern blot probe and RT-PCR primers, and the shNK1 and shNK2 regions from which sequences were derived for cloning into shRNA constructs.

PMEPA1 expression is strongly enhanced by TGF-β 6, 7, something which agrees with the two SMAD binding element motifs that we found conserved in its promoter ( Supplementary file S1). PMEPA1 function is not well understood, but it is believed to encode a transmembrane protein that with its cytoplasmic domain can bind SMAD proteins and can positively affect activation of Akt 7. Signaling pathways involving Akt and NF-κB are known to converge 8, which might be relevant for a possible indirect effect of NKILA through PMEPA1 on NF-κB functions. PMEPA1 levels were reported to be high in invasive MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, and low in non-invasive MCF-7 and T47D breast cancer cells, agreeing with observations for aggressive versus non-aggressive tumors 9. This is exactly opposite to the expression pattern observed by Liu et al. for NKILA in these cell lines and among tumors. PMEPA1 knockdown has been found to be able to attenuate growth and motility of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells 9, which is interesting since Liu et al. 1 found that forced NKILA expression (which might knockdown PMEPA1 expression) in MDA-MK-231 cells achieves similar effects. Consistent with these findings is the observation that high PMEPA1 expression in breast cancer is associated with poor patient prognosis 7, and high NKILA expression with better patient prognosis 1. Although there are also published PMEPA1 reports which are harder to reconcile with such a model (e.g. reference 10), and which are hard for us to validate, at least the above selected set of data suggests that NKILA has a negative effect on PMEPA1 function. More research on both NKILA and PMEPA1 will be necessary before conclusions can be made, but for now the possibility that NKILA can downregulate PMEPA1 expression appears to be a reasonable model 4, 5.

Liu et al. 1 concluded that NKILA interferes with pathways that involve NF-κB function, and we feel that in essence this conclusion can be believably deduced from their abundant experimental data. However, mechanistically Liu et al. only consider a direct interaction with NF-κB components and fail to consider an indirect effect through PMEPA1 regulation. Liu et al. 1 did find direct binding between the NF-κB component p65 and NKILA, but whether this can be considered as evidence of physiological specificity of NKILA for NF-κB is questionable. When they analyzed proteins that they could pull down with NKILA they only compared different NF-κB pathway components using Western blot analysis 1. In addition, when they quantified NKILA by RT-PCR on genetic material that co-precipitated with NF-κB factors, they did not exclude the possibility that they might be measuring genomic NKILA DNA 1.

Liu et al. 1 mapped the NKILA interaction with p65 to hairpin-prone regions A and B, and showed that the hairpin-prone region C can interact with NF-κB pathway factor IκBα (for hairpin-prone region locations see Figure 1). By mutation analysis, Liu et al. 1 found that all these three hairpin-prone regions are important for the inhibitory effect of NKILA on NF-κB activity. Although the relevance of this overlap is not clear, we point out that all three identified hairpin-prone regions, and also the region which Liu et al. 1 found to confer sensitivity to miRNA induced degradation, overlap with known PMEPA1 transcript regions ( Figure 1).

As an additional remark, we would like to state that the somewhat discussable manner in the way Liu et al. 1 performed or described some of their experiments (see our comments in Supplementary file S2) does not help to convey the image of a study which is solid in its quantitative aspects. However, despite our criticism, it is only fair to state here that according to our judgement the very elaborate study by Liu et al. 1 believably shows (1) how NKILA can bind ( in vitro) to NF-κB, (2) that NKILA can interfere with functions that involve NF-κB pathways, and (3) that low NKILA expression predicts poor clinical outcome in patients with breast cancer. But they should mend the open ends, which means providing more evidence of the specificity of the NKILA binding to NF-κB, and to take the possible effects of NKILA through regulation of PMEPA1 into consideration. In regard to the more general claim by Liu et al. 1 that there exists “a class of lncRNAs that regulate signal transduction at post-translational level”, we believe as before 11 that such a conclusion needs more evidence than currently has been presented. We hope that our present discussion leads to an increased interest in the PMEPA1-NKILA locus, because whatever mechanism may be correct, Liu et al. did provide evidence that this locus is clinically important in breast cancer.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declared that no grants were involved in supporting this work.

v1; ref status: indexed

Supplementary material

Supplementary file S1.Alignment of PMEPA1-NKILA promoter region sequences of representative animals and deduced PMEPA1 amino acid sequences for the species compared.

Click here to access the data. http://dx.doi.org/10.5256/f1000research.6400.s45984

Supplementary file S2.List of issues regarding the Liu et al. (2015). Cancer Cell 27, 370–381 paper which in our opinion need attention.

References

- 1. Liu B, Sun L, Liu Q, et al. : A Cytoplasmic NF-κB interacting Long Noncoding RNA Blocks IκB Phosphorylation and Suppresses Breast Cancer Metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2015;27(3):370–81. 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rae FK, Hooper JD, Nicol DL, et al. : Characterization of a novel gene, STAG1/PMEPA1, upregulated in renal cell carcinoma and other solid tumors. Mol Carcinog. 2001;32(1):44–53. 10.1002/mc.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Giannini G, Ambrosini MI, Di Marcotullio L, et al. : EGF- and cell-cycle-regulated STAG1/PMEPA1/ERG1.2 belongs to a conserved gene family and is overexpressed and amplified in breast and ovarian cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2003;38(4):188–200. 10.1002/mc.10162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Villegas VE, Zaphiropoulos PG: Neighboring gene regulation by antisense long non-coding RNAs. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(2):3251–66. 10.3390/ijms16023251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li Q, Su Z, Xu X, et al. : AS1DHRS4, a head-to-head natural antisense transcript, silences the DHRS4 gene cluster in cis and trans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(35):14110–5. 10.1073/pnas.1116597109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brunschwig EB, Wilson K, Mack D, et al. : PMEPA1, a transforming growth factor-beta-induced marker of terminal colonocyte differentiation whose expression is maintained in primary and metastatic colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63(7):1568–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Singha PK, Pandeswara S, Geng H, et al. : TGF-β induced TMEPAI/PMEPA1 inhibits canonical Smad signaling through R-Smad sequestration and promotes non-canonical PI3K/Akt signaling by reducing PTEN in triple negative breast cancer. Genes Cancer. 2014;5(9–10):320–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Meng F, Liu L, Chin PC, et al. : Akt is a downstream target of NF-kappa B. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(33):29674–80. 10.1074/jbc.M112464200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Singha PK, Yeh IT, Venkatachalam MA, et al. : Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta)-inducible gene TMEPAI converts TGF-beta from a tumor suppressor to a tumor promoter in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70(15):6377–83. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Anazawa Y, Arakawa H, Nakagawa H, et al. : Identification of STAG1 as a key mediator of a p53-dependent apoptotic pathway. Oncogene. 2004;23(46):7621–7. 10.1038/sj.onc.1207270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dijkstra JM, Ballingall KT: Non-human lnc-DC orthologs encode Wdnm1-like protein [v2; ref status: indexed, http://f1000r.es/4el]. F1000Res. 2014;3:160. 10.12688/f1000research.4711.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]