Abstract

Understanding the significance of bacterial species that colonize and persist in cystic fibrosis (CF) airways requires a detailed examination of bacterial community structure across a broad range of age and disease stage. We used 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing to characterize the lung microbiota in 269 CF patients spanning a 60 year age range, including 76 pediatric samples from patients of age 4–17, and a broad cross-section of disease status to identify features of bacterial community structure and their relationship to disease stage and age. The CF lung microbiota shows significant inter-individual variability in community structure, composition and diversity. The core microbiota consists of five genera - Streptococcus, Prevotella, Rothia, Veillonella and Actinomyces. CF-associated pathogens such as Pseudomonas, Burkholderia, Stenotrophomonas and Achromobacter are less prevalent than core genera, but have a strong tendency to dominate the bacterial community when present. Community diversity and lung function are greatest in patients less than 10 years of age and lower in older age groups, plateauing at approximately age 25. Lower community diversity correlates with worse lung function in a multivariate regression model. Infection by Pseudomonas correlates with age-associated trends in community diversity and lung function.

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is characterized by recurrent airway infection, inflammation and progressive decline in lung function. Infection with key organisms such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia complex (Bcc) has been associated with the frequent exacerbations of airway dysfunction and progressive functional decline that are the hallmarks of the disease1,2,3.

Over the last decade, cross-sectional and longitudinal studies of bacterial taxa using culture-independent microbial detection methods such as terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) and 16S rRNA gene sequencing, have identified polymicrobial communities in the airways of CF patients that exceed the complexity captured by traditional culture4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. Significant heterogeneity in bacterial community composition has been demonstrated within groups of clinically similar patients5,6,7. Although the abundance of individual taxa (such as Gemella spp. and the Streptococcus anginosus group), ecological diversity, and community stability are potentially associated with disease status8,10,14, no single static or dynamic metric or bacterial taxon has emerged that consistently explains the heterogeneity of disease within otherwise similar hosts.

Culture-based methods have demonstrated the clinical significance of infection with pathogens such as P. aeruginosa. Molecular methods have demonstrated that not only their presence or absence, but also their relative abundance, dominance over other taxa, and temporal stability are potentially important determinants of ecological and clinical change in lung disease10,15. While studies of the CF microbiome to date have largely focused on adult patients, we expand this base of knowledge by including 76 pediatric patients less than 18 years old (28% of the total sample). This early time period is particularly interesting from the perspective of CF microbiology since community composition is more dynamic in pediatric patients than in adults16,17. Here, we report a cross-sectional survey of the bacterial community in sputum samples from 269 CF patients spanning a 60-year age range and a wide range of lung function.

Results

Clinical and microbiological characteristics of patients

During the study period, 76 pediatric (<18 years old) and 193 adult CF patients provided at least one expectorated sputum sample for analysis. Complete clinical data was available for 73 pediatric and 191 adult patients. The characteristics of these patients are reported in Table 1. Pancreatic insufficiency was more common in pediatric patients (P < 0.001). A larger proportion of adult patients had intermediate (FEV1 < 70% predicted) or advanced (FEV1 < 40% predicted) disease (68.6% vs 44.3% of pediatric patients, P = 0.001) and the median FEV1 was lower in the adult cohort, reflecting the progression of disease with increasing age (P < 0.001). Adult patients were more likely than pediatric patients to be infected by Bcc or Aspergillus species by sputum culture (P = 0.037, 0.011 respectively), with a trend towards increased infection with P. aeruginosa (P = 0.085).

Table 1. Study participant summary by age category.

| <18 | 18+ | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 76 | 193 | - |

| Median Age (Range) | 12 (4-17) | 29 (18-64) | - |

| Male (%) | 33 (43.4) | 112 (59.2) | 0.041 |

| CFTR Genotype | |||

| dF508/dF508 | 40 (52.6) | 87 (45.8) | |

| dF508/other | 23 (30.3) | 69 (36.3) | ns |

| other/other | 13 (17.1) | 34 (17.9) | |

| Median BMI Z-score (<18), BMI (18+) (Range) | −0.6 (−3-1.4)* | 22.2 (15.3-38.3) | - |

| Pancreatic insufficiency (%) | 71 (93.4) | 129 (72.1)* | <0.001 |

| Disease stage | |||

| Early | 39 (55.7)* | 59 (31.4)* | |

| Intermediate | 25 (35.7)* | 94 (50.0)* | <0.001 |

| Advanced | 6 (8.6)* | 35 (18.6)* | |

| FEV1% predicted (median, range) | 73 (26.6-117)* | 60.5 (15-111)* | <0.001 |

| Clinical status at sputum collection | |||

| Baseline | 32 (42.1) | 100 (51.8) | |

| Exacerbation | 15 (19.7) | 27 (13.9) | |

| Treatment | 9 (11.8) | 38 (19.7) | <0.001 |

| Recovery | 7 (9.2) | 11 (5.7) | |

| Other | 13 (17.1) | 17 (8.8) | |

| Sputum culture positivity at study visit | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 19 (25.0) | 71 (37.2) | 0.085 |

| Burkholderia cepacia complex | 4 (5.3) | 28 (14.7) | 0.037 |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 8 (10.5) | 19 (9.9) | ns |

| Mycobacterium species | 0 | 0 | - |

| Aspergillus species | 13 (17.1) | 64 (33.5) | 0.011 |

ns - not significant

*Indicates missing data

Individual sample and genus characteristics

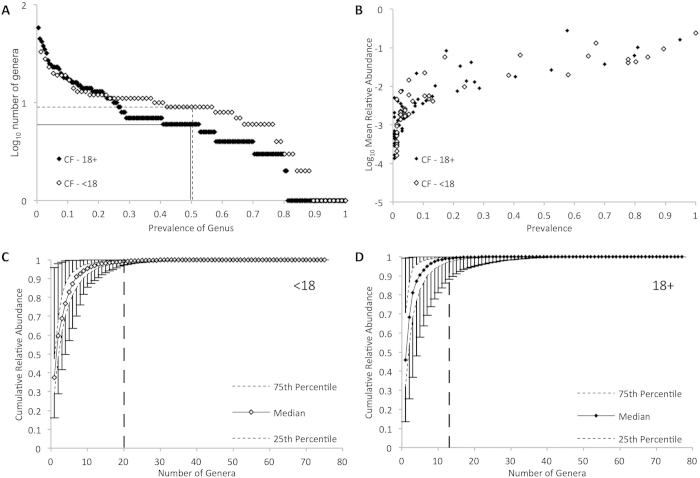

After quality and abundance filtering, 87 genera were identified across all samples. The size of the core microbiota of adult and pediatric samples, arbitrarily defined in our study as genera with a relative abundance of ≥1% of sequence in ≥50% of samples, were similar in both groups (Fig. 1A, Table 2). Streptococcus, Prevotella, Rothia, Veillonella and Actinomyces were core genera in both groups, while Neisseria, Haemophilus and Gemella were unique core genera in pediatric samples and Pseudomonas was unique to the adult core microbiota. In both groups, the genera with the greatest prevalence also had the greatest mean relative abundance (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Genus level summary of bacterial population structure in cystic fibrosis (CF) in pediatric and adult sputum samples by 16S rRNA gene sequencing, after exclusion of operational taxonomic units that account for less than 0.005% sequence in the entire dataset. (A) Number of genera in pediatric (open diamonds) and adult (filled diamonds) specimens plotted by prevalence. Dashed (pediatric) and solid (adult) lines indicate core microbiota (genus present in >50% of samples). (B) Mean relative abundance of genera in pediatric (open diamonds) and adult (filled diamonds) specimens plotted by prevalence (C and D) Cumulative relative abundance of genera within a sputum sample of pediatric (C) and adult (D) CF patients plotted by number of genera. Error bars indicate range of values, and vertical dashed lines indicate the number of OTUs accounting for 99% of total sequence.

Table 2. Dominance proportion of selected genera across specimens.

| Genus | Present* N (% of all samples) | Most abundant N (% of all samples) | Dominantt N (% of all samples) | Dominance proportion§ | Maximum Relative Abundance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <18 years | |||||

| Streptococcus | 76 (100.0) | 34 (44.7) | 12 (15.8) | 0.16 | 0.58 |

| Rothia | 67 (88.1) | 6 (7.9) | 0 | 0 | 0.41 |

| Prevotella | 64 (84.2) | 3 (3.9) | 0 | 0 | 0.43 |

| Actinomyces | 61 (80.2) | 1 (1.3) | 0 | 0 | 0.20 |

| Veillonella | 59 (77.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.18 |

| Gemella | 58 (76.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.17 |

| Haemophilus | 51 (67.1) | 13 (17.1) | 9 (11.8) | 0.18 | 0.81 |

| Neisseria | 49 (64.5) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) | 0.02 | 0.29 |

| Staphylococcus | 32 (42.1) | 6 (7.9) | 3 (3.9) | 0.09 | 0.96 |

| Porphyromonas | 29 (38.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.18 |

| Fusobacterium | 18 (23.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.23 |

| Pseudomonas | 13 (17.1) | 6 (7.9) | 6 (7.9) | 0.46 | 0.86 |

| Solobacterium | 9 (11.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.12 |

| Leptotrichia | 8 (10.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.06 |

| Stenotrophomonas | 8 (10.5) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) | 0.13 | 0.57 |

| Oribacterium | 5 (6.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.04 |

| Achromobacter | 4 (5.3) | 2 (2.6) | 2 (2.6) | 0.50 | 0.52 |

| Campylobacter | 2 (2.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.02 |

| Burkholderia | 2 (2.6) | 1 (1.3) | 0 | 0 | 0.51 |

| Lactobacillus | 1 (1.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.04 |

| Bifidobacterium | 1 (1.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.02 |

| Scardovia | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) | 0 | 0 | 0.33 |

| 18+ years | |||||

| Streptococcus | 183 (94.8) | 38 (19.7) | 14 (7.3) | 0.08 | 0.78 |

| Prevotella | 156 (80.8) | 24 (12.4) | 2 (1) | 0.01 | 0.39 |

| Rothia | 154 (79.8) | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0.35 |

| Veillonella | 135 (69.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.22 |

| Pseudomonas | 111 (57.5) | 71 (36.8) | 61 (31.6) | 0.55 | 0.99 |

| Actinomyces | 101 (52.3) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 0.21 |

| Gemella | 78 (40.4) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 0.16 |

| Porphyromonas | 52 (26.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.17 |

| Haemophilus | 50 (25.9) | 9 (4.7) | 7 (3.6) | 0.14 | 0.90 |

| Fusobacterium | 47 (24.4) | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0.42 |

| Staphylococcus | 43 (22.3) | 9 (4.7) | 4 (2.1) | 0.09 | 0.64 |

| Burkholderia | 34 (17.6) | 22 (11.4) | 16 (8.3) | 0.47 | 0.97 |

| Neisseria | 27 (14.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 0.21 |

| Oribacterium | 25 (13.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.11 |

| Leptotrichia | 16 (8.3) | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0.20 |

| Stenotrophomonas | 15 (7.8) | 5 (2.6) | 3 (1.6) | 0.20 | 0.95 |

| Solobacterium | 14 (7.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.19 |

| Campylobacter | 13 (6.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.03 |

| Achromobacter | 6 (3.1) | 2 (1) | 1 (0.5) | 0.17 | 0.73 |

| Lactobacillus | 6 (3.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.20 |

| Bifidobacterium | 5 (2.6) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0.20 | 0.58 |

| Inquilinus | 3 (1.6) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 0.32 |

| Bordetella | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 1.00 | 0.95 |

| Proteus | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 0.30 |

*Specimen >0.01 relative abundance

tDominance = Genus is most abundant AND > 2x the relative abundance of next most abundant genus

§=(Number of samples in which genus is dominant)/(Number in which it is present with RA >0.01)

A small subset of genera comprised most of the bacterial sequences detected in any sample (Fig. 1C and D, Table 3). The median number of genera required to account for half of the sequences in each sample was two in both groups, while a median of 20 and 13 genera accounted for 99% of the sequence in pediatric and adult patients, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3. Relative sequence abundance by number of genera in each patient.

| <18 (median, range) | 18+ (median, range) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of genera >0.01 relative abundance | 10 (2-15) | 8 (1-17) |

| OTU50 | 2 (1-5) | 2 (1-5) |

| OTU75 | 4 (1-8) | 3 (1-9) |

| OTU90 | 7 (1-13) | 5 (1-15) |

| OTU99 | 20 (4-28) | 13 (1-35) |

OTU50: number of OTUs that represent 50% of the overall sequence (per patient)

OTU75: number of OTUs that represent 75% of the overall sequence (per patient)

OTU90: number of OTUs that represent 90% of the overall sequence (per patient)

OTU99: number of OTUs that represent 99% of the overall sequence (per patient)

A dominant genus (the most abundant genus with at least twice the abundance of the second most abundant genus) was present in 45% of pediatric samples and 57% of adult samples. Streptococcus, Haemophilus, Pseudomonas, Staphylococcus and Achromobacter were dominant in multiple pediatric samples in descending order of frequency, while Neisseria and Stenotrophomonas were each dominant in one pediatric sample. Pseudomonas, Burkholderia, Streptococcus, Haemophilus and Staphylococcus were the dominant genus in descending order of frequency in adults (Table 2). The median relative abundance of the most abundant genus in each sample was 0.38 in pediatric samples (IQR 0.29-0.50) and 0.46 in adults (IQR 0.32-0.71), the median relative abundance of dominant genera was 0.64 (range 0.26-0.99).

Rothia, Prevotella, Gemella, Actinomyces and Veillonella were prevalent in both pediatric and adult samples, but were seldom or never the dominant genus. Pseudomonas was more prevalent in adults but tended to be dominant in both pediatric and adult samples in which it was present (Table 2). Streptococcus, Burkholderia, Achromobacter, Stenotrophomonas and Haemophilus were commonly the dominant genus in samples in which they were present. Bordetella accounted for 95% of the sequence in one adult specimen from a patient identified by culture as being chronically infected by Bordetella avium, but was not present in any other samples. In addition to having a high dominance proportion (the number of samples in which the genus was dominant divided by the total number of samples in which it was present with >1% relative abundance), Pseudomonas and Burkholderia, when dominant, accounted for a larger proportion of the community than Streptococcus in Streptococcus-dominant samples (72.8%, 78.2% and 47.1% of sequence in adult samples respectively, P < 0.0005). Only five genera (Pseudomonas, Burkholderia, Stenotrophomonas, Haemophilus and Bordetella) comprised more than 90% of any sample, and only in samples from adult patients.

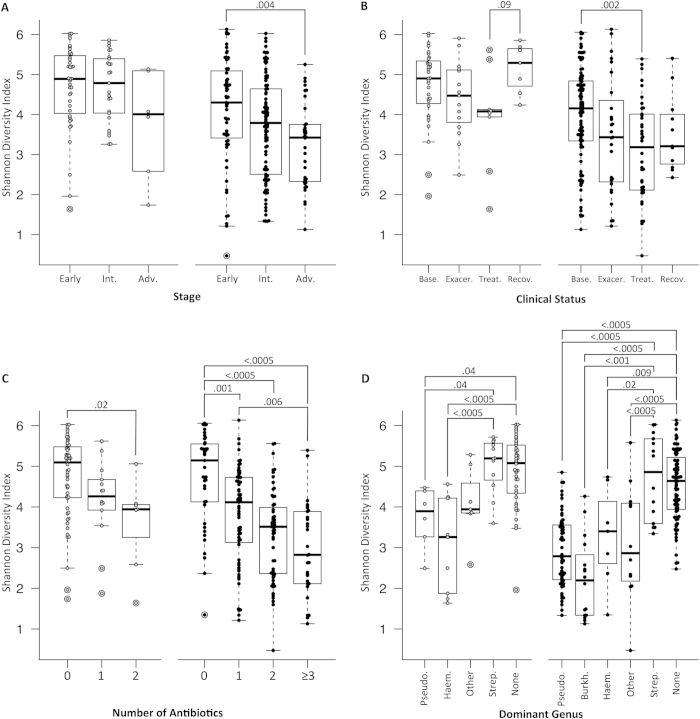

Within sample (alpha) diversity

Advanced disease stage was associated with lower diversity in adult patients (P = 0.004, Fig. 2A). This difference was not statistically significant in pediatric patients; however, only 6 pediatric patients had advanced disease. Baseline samples were more diverse than treatment samples for adults (P = 0.002, Fig. 2B). There was a stepwise, statistically significant decrease in diversity associated with increased number of antibiotics prescribed in both cohorts (Fig. 2C). Streptococcus dominance was associated with higher community diversity in both datasets (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Within-sample (alpha) diversity of sputum specimens from CF patients. Boxplots represent minimum-25th centile-median-75th centile-maximum values and markers indicate individual patients. Open markers indicate pediatric patients and filled markers indicate adult patients. Alpha diversity was summarized using the Shannon diversity index, with diversity increasing on the y axis. Samples were grouped and compared by (A) disease stage (B) clinical status, (C) number of antibiotics being administered at the time of sample collection, and (D) dominant genus. P-values represent the results of t-tests between groups, within pediatric and adult cohorts. Stage, clinical status, treatment groups and dominant genus are defined in the Methods section. Abbreviations: Int.= intermediate, Adv.= advanced, Base.= baseline, Exacer. = exacerbation, Recov. = recovery, Pseudo. = Pseudomonas, Haem. = Haemophilus, Strep. = Streptococcus, Burk. = Burkholderia, None = No dominant genus.

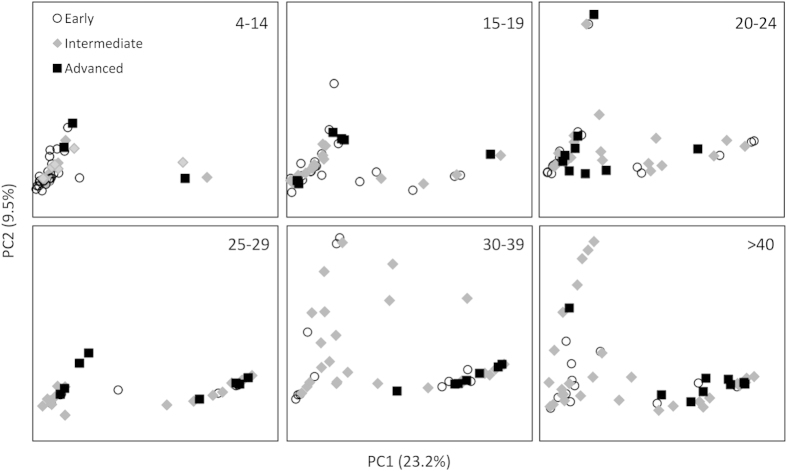

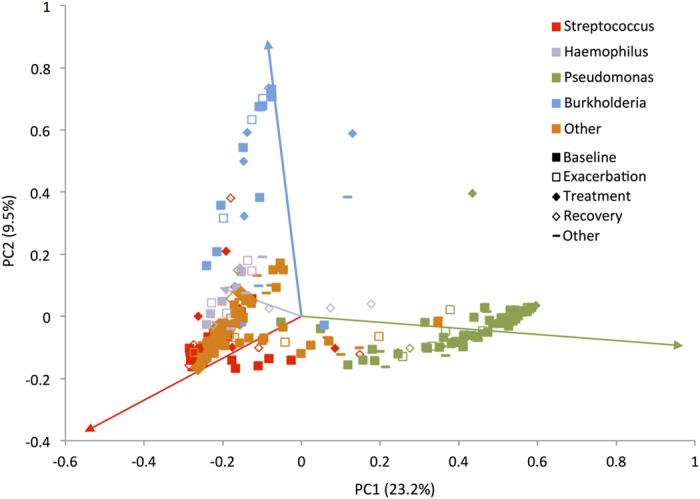

Between sample (beta) diversity

We assessed inter-sample variability in community structure (beta diversity) using unsupervised principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of Bray-Curtis dissimilarity (Fig. 3). The relative abundance of Pseudomonas, Burkholderia, Streptococcus and Haemophilus largely drove ordination (Fig. 3). Samples did not cluster by clinical status at the time of sample acquisition (baseline, exacerbation, treatment, recovery or other). Notably, Bray-Curtis ordination was influenced by disease stage differently across the age groups, with clustering based on disease stage becoming more apparent after age 30 (Fig. 4). This analysis did not reveal any grouping of bacterial community structures by gender, CFTR genotype, pancreatic status, FEV1, FVC or BMI.

Figure 3.

Between-sample (beta) diversity of sputum specimens from CF patients. Bray-Curtis dissimilarity principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) was used to generate ordination of beta-diversity in two dimensions. Principal coordinates 1 and 2 (PC1 and PC2) explain 23.2% and 9.5% of the variance in Bray-Curtis dissimilarity respectively (x and y axes). Increasing distance in two-dimensional space represents increasingly dissimilar community structures. The marker style indicates samples were obtained from patients at clinical baseline, exacerbation, treatment, recovery or other as defined in the Methods section. Samples are colored according to most abundant genus. Colored arrows in the plot indicate Pearson correlation coefficients between genus relative abundance and each principal coordinate, with the line colors corresponding to the genus color in the legend.

Figure 4.

PCoA by Bray-Curtis dissimilarity was plotted by age group as indicated in the upper right corner of each panel. Markers represent individual patients and marker style indicates disease stage at the time of sample collection. Principal coordinates 1 and 2 correlate with relative abundance of Pseudomonas and Burkholderia, respectively as in Fig. 3.

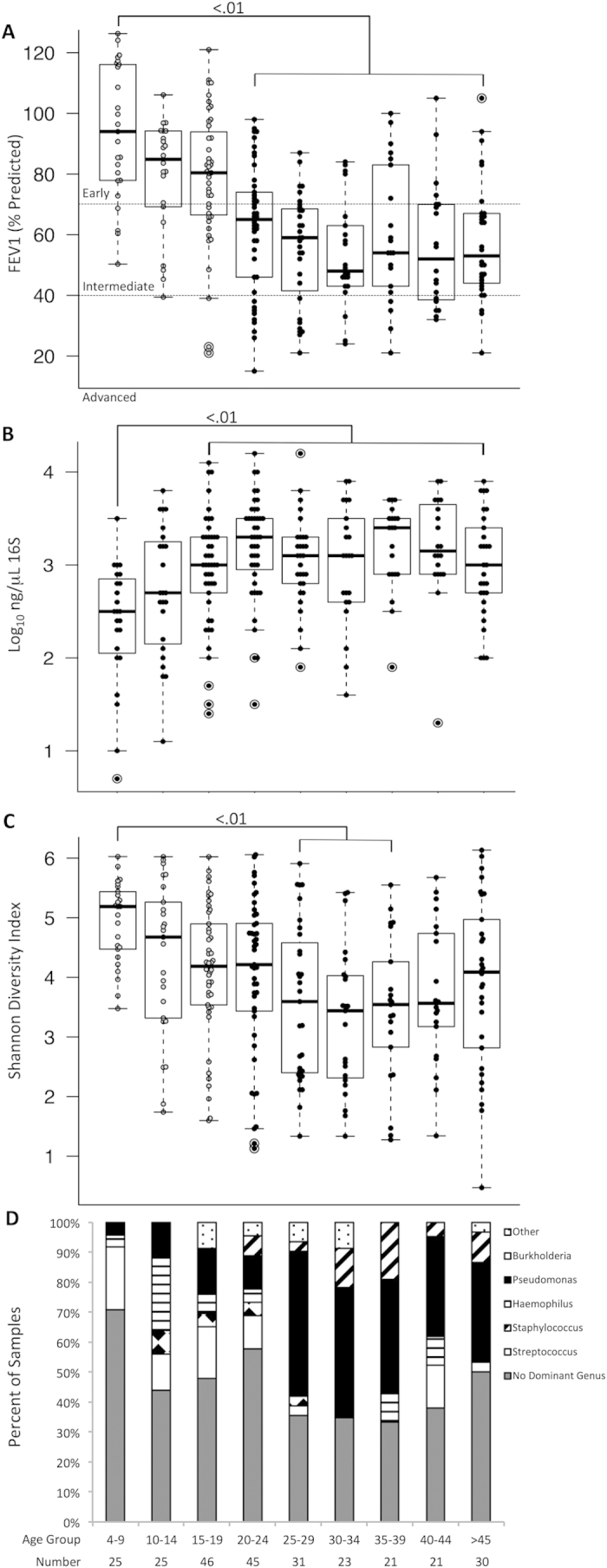

Age group and disease status associated bacterial community changes

Patients were stratified into age groups and compared based on lung function, community diversity and dominant genera (Fig. 5). As expected, FEV1 was lower in older age groups, with the lowest median FEV1 in patients aged 30-34 years (Fig. 5A). Bacterial density (log10 ng/μL of 16S rRNA gene by quantitative PCR) was greatest at ages 20-24 (Fig. 5B). Diversity was also lower in older age groups, and differences in community diversity paralleled lung function across age groups (diversity nadir 30-34 years, Fig. 5C). In addition, the lower lung function and diversity observed in older age groups coincided with a higher proportion of samples dominated by Pseudomonas or Burkholderia and a decreased proportion of Streptococcus dominance and samples without a dominant genus (Fig. 5D). If dichotomized at age 25, Streptococcus dominance and no dominant genus account for 69% of the samples from younger patients, but only 43% of samples from older patients, whereas Pseudomonas and Burkholderia dominant samples comprise only 14% of samples from patients under 25 years but 49% of cases from patients 25 years or older (Chi-squared of dominant taxa in <25 or ≥25 year old patients, P < 0.0005).

Figure 5.

(A) Age dependent changes in lung function (FEV1% predicted), (B) bacterial load (ng/μL 16S rRNA), (C) alpha diversity (Shannon diversity index) and (D) dominant genus (defined in Methods) demonstrate concordant changes in lung function, diversity and increased prevalence of Pseudomonas and Burkholderia with increasing age. Chi-squared significance for panel D is P < 0.0005.

Predictors of FEV1 by multivariate linear regression

Given the observed correlation of bacterial diversity, density and dominant taxa for lung function across age groups, we performed multivariate linear regression to ascertain which features of the lung microbiota independently predict lung function while controlling for the influence of host factors. Factors with known significance and potential confounders present in our dataset were entered into the multivariate model prior to sequentially testing diversity (SDI), bacterial density (log10 16s rRNA gene by quantitative PCR) and dominant taxa based on the strategy outlined in the methods section. The final model included age, BMI z-score, pancreatic insufficiency, SDI and Pseudomonas dominance (adjusted R2 = 0.315, df = 5, F = 22.9, P < 0.0005, Table 4). Increasing age, pancreatic insufficiency, increasing number of antibiotics and Pseudomonas dominance negatively correlated with lung function, while increasing BMI and diversity positively correlated with lung function in our model.

Table 4. Multivariate regression model for predicting lung function (FEV1 % predicted).

| Initial Model* | Final Modelt | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β (95% CI, lower, upper bound) | p-value | β (95% CI, lower, upper bound) | p-value |

| Constant | 84.9 (65.8,104.2) | <0.0005 | 80.6 (66.5,94.6) | <0.0005 |

| Age (years) | −0.6 (−0.8,−0.4) | <0.0005 | −0.6 (−0.8,−0.4) | <0.0005 |

| Body Mass Index | 7.5 (5,10) | <0.0005 | 7.3 (4.9,9.8) | <0.0005 |

| Pancreatic Insufficiency | −9.5 (−17,−2.1) | 0.012 | −8.8 (−15.4,−2.2) | 0.009 |

| Antibiotic number | −1.8 (−4.1,0.5) | 0.132 | - | - |

| Male sex | 2.8 (−2.4,8) | 0.291 | - | - |

| F508 homozygous | 0.8 (−4.5,6.1) | 0.768 | - | - |

| Diversity (SDI) | 2.2 (−0.4,4.8) | 0.098 | 2.5 (0.5,4.6) | 0.016 |

| Log10 16S (ng/μL) | −1.2 (−5.1,2.6) | 0.532 | - | - |

| Dominant genus | ||||

| Pseudomonas | 1.2 (−11,13.5) | 0.107 | −7.6 (−13.7,−1.5) | 0.015 |

| Burkholderia | −0.5 (−8.9,7.9) | 0.844 | - | - |

| Streptococcus | 7.8 (−3.7,19.3) | 0.904 | - | - |

| Haemophilus | −3.9 (−13.4,5.7) | 0.182 | - | - |

| Other | 84.9 (65.8,104.2) | 0.426 | - | - |

*Preliminary model = statistics at the time of variable entry as described in materials and methods.

tFinal Model = statistics at the time of finalization of the multivariate model with all final variables included.

Discussion

We describe the bacterial community structure of sputum samples from 269 cystic fibrosis patients across a broad range of age, disease stage, clinical status and treatment using a culture-independent method. This is the largest cohort of CF patients spanning both adult and pediatric populations for whom sputum has been analysed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing yet published, and includes a large number of patients younger than 18 years of age. We observed several clear features of bacterial community structure in CF sputum and their relationship with disease states.

Firstly, the airways of CF patients share only a small number of common taxa, but otherwise demonstrate a high degree of inter-individual variability in community structure, composition and diversity, confirming the results of smaller studies5,6,7. In pediatric and adult CF patients, the shared core microbiome was small, and consisted largely of genera not considered to be traditional CF pathogens, namely Streptococcus, Rothia, Veillonella and Actinomyces. Pseudomonas, a prototypic CF pathogen, was a member of only the adult core microbiota. A small number of taxa accounted for the bulk of bacterial sequences present in any sample, and approximately half of all patients had a bacterial community dominated by a single genus.

Secondly, the observed taxa in the CF lung vary in their relative abundance and dominance of the bacterial community. Only six genera had a dominance proportion >0.10 and a maximum relative abundance >0.70: Pseudomonas, Burkholderia, Stenotrophomonas, Achromobacter, Haemophilus and Bordetella. Of the remaining genera, only Staphylococcus, Streptococcus and Bifidobacterium were observed at a relative abundance of at least 0.50 in one or more samples.

In addition, whereas within sample diversity correlated with several patient, treatment and microbial factors, between patient diversity was largely driven by the age-associated relative abundance of Pseudomonas and Burkholderia. Age, disease stage, treatment and dominant genus were found to significantly correlate with differences in alpha diversity, confirming the observations of previous published reports of smaller datasets8,11,12,13,16,17,18,19,20. The largest differences between patient communities noted in our study were the greater prevalence and relative abundance of Pseudomonas and Burkholderia in older age groups. As patients with CF age, their risk of acquisition of these organisms increases17,21, and we observed a stepwise progression in the prevalence and relative abundance of these two important genera with increasing age. A notable increase in Pseudomonas and Burkholderia dominance was observed in patients aged 25 and older, which coincided with the lowest lung function and sample diversity observed in any age group. Beyond this age, there are few differences in overall community structure, diversity or lung function in surviving adult patients, and it is possible that the establishment of these CF associated pathogens is largely complete by age 20-25. These findings corroborate the findings of smaller cross-sectional studies of CF microbiota over a large age range, including the ‘plateau’ of community and functional change at approximately 25 years of age17,22.

This study also demonstrated that sample diversity was positively correlated with lung function after controlling for host factors. Multivariate regression of clinical and bacterial features for prediction of lung function revealed that age, BMI z-score, pancreatic insufficiency, diversity and Pseudomonas dominance independently predict lung function. The observation that diversity positively correlates with lung function agrees with other studies in CF and non-CF bronchiectasis8,9,23. Our and previously published analyses do not address causality, however, and it remains uncertain whether the relationship between disease stage and diversity is causal.

This study has important caveats. The prevalence of infection with Pseudomonas in this study was lower than published registry data for both pediatric and adult patients24. Similarly, none of the included specimens were culture-positive for Mycobacterium, despite recently reported prevalence rates of nearly 10%25. However, prevalence of all species by culture in our study was determined for the study sample only, not for historical samples from each patient, and thus is unsurprisingly lower than published reports which generally define infection as culture positivity within a time range, rather than at a single timepoint.

Adequacy of sampling in CF microbiome studies is difficult to conclusively ascertain and is a challenge in similar studies. Culture-independent analysis by 16S rRNA gene sequencing is not uniformly sensitive to the detection of all bacterial taxa, such as Staphylococcus, in the absence of specific sample processing procedures26. Our study was not designed to systematically compare within-sample relationships between culture and 16S rRNA sequence data. As such, our analysis of Staphylococcal relative abundance should be interpreted cautiously.

Since our cohort did not include paired specimens from the same patient, this analysis was not designed to identify differences in bacterial community characteristics occurring at times of different disease activity (such as during an exacerbation). Given the highly variable bacterial community structure in CF which we and others5,6,7 have observed, between-patient differences are likely to obscure important within-patient trends occurring during exacerbations.

Furthermore, our analysis was not designed to assess the impact that rare or very low abundance taxa (<1% relative abundance) may have on the biology of the CF airway, but rather to assess trends in community structure over a broad range of ages and disease stage. Very low abundance and rare taxa may be critical determinants of pathological processes in the CF lung. Our observations highlight the heterogeneity between patients and confirm the need for longitudinal analysis in individual patients and groups of patients to identify factors associated with disease exacerbations, disease progression and response to treatment. Our method resolved community composition to the genus level only. Significant within-genus or intra-species variability in community composition may have important effects on community behavior and disease pathogenesis and has the potential to explain cross-sectional variability in disease status that is not apparent at the genus level.

Despite these caveats, our data agree with prior reports of CF microbiota, and extend these observations to a broader age range of patients, particularly those less than 18 years of age, a group that is not well represented in previously published reports. Our principal findings agree with and extend those of smaller studies of mostly adult patients showing high inter-individual variability in community structure5,6,7, a common core microbiota9, age associated changes in community composition16,17, and disease stage associated decreases in diversity8,11,12,13,16,17,18,19,20.

Longitudinal studies identifying microbial and host risk factors for infection with patho-adapted taxa such as Pseudomonas and Burkholderia, and mechanistic studies elucidating the interactions of these taxa with other colonizing organisms, as well as exploration of possible causal relationships between community diversity and disease manifestations would be illuminating.

Methods

Study enrollment, sample and data collection

This study received approval from the research ethics boards of both St. Michael’s Hospital and the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Canada. Patients provided informed consent and were enrolled prospectively at The Hospital for Sick Children and St. Michael’s Hospital between 2010 and 2013. Height, weight, forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), age, sex, disease stage, antimicrobial therapy, clinical status, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) mutation, pancreatic status, and visit outcome were recorded for the day of sample collection. Expectorated sputa were collected for all patients - no oropharyngeal samples were used. Pediatric samples were split into aliquots, one for culture and one for nucleic acid extraction, while adults provided two samples in parallel at each clinic visit. Samples for sequencing were treated with sputolysin and frozen for subsequent processing. Quantitation of 16S rRNA gene copy number was performed by quantitative PCR based on published protocols27.

Si-Seq 16S rRNA gene analysis and informatics

Sequencing was performed at the Centre for the Analysis of Genome Evolution and Function (CAGEF) at the University of Toronto as previously described using an Illumina GAIIx28. An in-house Java script was used to prepare the sequence for downstream analysis using MACQIIME29. Chimeric reads were removed using reference-based chimera detection with USEARCH30. Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were picked against a SI-Seq structured reference set using a similarity of 0.87 (corresponding to the genus level with the SI-Seq method), with premature termination turned off. Taxonomy was assigned using an RDP structured dataset using UCLUST30 with --max_accepts set to 0 and similarity set to 0.97, (empirically determined to produce the highest consistency identification at the genus level using Pseudomonas aeruginosa controls)28. Unassigned OTUs were identified with BLASTN31. OTUs representing less than 0.005% of overall sequence were removed. At this stage, the median number of sequences/sample was 67,812 (IQR 42,835-87,773). For calculation of Shannon diversity index (SDI), samples were rarefied to 1500 sequences to account for the effects of sequencing depth on diversity, with a median Good’s coverage of 0.972 (IQR 0.955-0.979) at that sampling depth. Diversity and principal coordinates analyses were performed using MACQIIME with default settings.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22 (IBM). Means were compared using T-tests or ANOVA with Bonferroni correction as needed. Chi-squared tests were used to test proportions. A multivariate linear regression model predicting FEV1 (% predicted) was built by entering all variables, then using backwards removal to identify variables in the final model.

Definitions

Disease stage, pancreatic insufficiency, FEV1, and FVC were defined as previously reported32,33. BMI z score was calculated using the method described in Flegal et al.34 using age-specific parameter values from the Centers for Disease Control ( www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/percentile_data_files.htm). For adults over 20 years old, the age values for BMI z score were calculated based on an age of 2035. Antibiotic number equaled the number of antibacterials of any type being taken on the day of the visit (including inhaled antibiotics). Clinical status was defined as ‘baseline’, ‘exacerbation’, ‘treatment’ or ‘recovery’ using the criteria of Zhao et al.11. Samples not meeting these criteria were categorized as ‘other’ and included patients receiving new prescriptions for steroids, antifungals or antibiotics for an indication other than a pulmonary exacerbation (e.g. an extra-pulmonary infection). ‘Dominant genus’ was defined as any genus whose relative abundance was at least twice that of the next most abundant genus10 or if no such genus was present, ‘no dominant genus’.

All methods were performed in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Author Contributions

B.C., D.M.H. and D.S.G. drafted the manuscript. B.C. created all figures and tables. D.E.T., S.D., S.T.C., V.B., Y.C.W.Y., V.J.W. and Y.Z. enrolled patients, collected clinical data and samples, and processed samples for sequencing. P.W.W., A.S., Y.G., J.D.C., S.T.C. and B.C. sequenced samples and processed sequence data. B.C., J.D.C., A.S., Y.G., V.J.W., D.M.H. and D.S.G. analyzed and interpreted the data. B.C., Y.C.W.Y., V.J.W., D.M.H., D.S.G. conceived the study design. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Coburn, B. et al. Lung microbiota across age and disease stage in cystic fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 5, 10241; doi: 10.1038/srep10241 (2015).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by: the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) [Canadian Microbiome Initiative Emerging Team Grant (CMF108027)]; the National Sanitarium Association; and Cystic Fibrosis Canada. Dr. Guttman is supported by a Canada Research Chair in Comparative Genomics. Dr. Coburn is recipient of a CIHR Fellowship.

References

- Kosorok M. R. et al. Acceleration of lung disease in children with cystic fibrosis after Pseudomonas aeruginosa acquisition. Pediatr Pulmonol 32, 277–287 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang N. N. et al. Clinical features, survival rate, and prognostic factors in young adults with cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Med 82, 871–879 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin L. O., Byard P. J. & Davis P. B. Effect of Pseudomonas cepacia colonization on survival and pulmonary function of cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin Epidemiol 43, 125–131 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surette M. G. The cystic fibrosis lung microbiome. Ann Am Thorac Soc 11 Suppl 1, S61–65, 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201306-159MG (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delhaes L. et al. The airway microbiota in cystic fibrosis: a complex fungal and bacterial community--implications for therapeutic management. PLoS One 7, e36313, 10.1371/journal.pone.0036313 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blainey P. C., Milla C. E., Cornfield D. N. & Quake S. R. Quantitative analysis of the human airway microbial ecology reveals a pervasive signature for cystic fibrosis. Sci Transl Med 4, 153ra130, 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004458 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stressmann F. A. et al. Analysis of the bacterial communities present in lungs of patients with cystic fibrosis from American and British centers. J. Clin Microbiol 49, 281–291, 10.1128/JCM.01650-10 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stressmann F. A. et al. Long-term cultivation-independent microbial diversity analysis demonstrates that bacterial communities infecting the adult cystic fibrosis lung show stability and resilience. Thorax 67, 867–873, 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200932 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Gast C. J. et al. Partitioning core and satellite taxa from within cystic fibrosis lung bacterial communities. ISME J. 5, 780–791, 10.1038/ismej.2010.175 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmody L. A. et al. Changes in cystic fibrosis airway microbiota at pulmonary exacerbation. Ann Am Thorac Soc 10, 179–187, 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201211-107OC (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J. et al. Decade-long bacterial community dynamics in cystic fibrosis airways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 5809–5814, 10.1073/pnas.1120577109 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodor A. A. et al. The adult cystic fibrosis airway microbiota is stable over time and infection type, and highly resilient to antibiotic treatment of exacerbations. PLoS One 7, e45001, 10.1371/journal.pone.0045001 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunney M. M. et al. Use of culture and molecular analysis to determine the effect of antibiotic treatment on microbial community diversity and abundance during exacerbation in patients with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 66, 579–584, 10.1136/thx.2010.137281 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley C. D. et al. A polymicrobial perspective of pulmonary infections exposes an enigmatic pathogen in cystic fibrosis patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105, 15070–15075, 10.1073/pnas.0804326105 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers G. B. et al. A novel microbiota stratification system predicts future exacerbations in bronchiectasis. Ann Am Thorac Soc 11, 496–503, 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201310-335OC (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klepac-Ceraj V. et al. Relationship between cystic fibrosis respiratory tract bacterial communities and age, genotype, antibiotics and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ Microbiol 12, 1293–1303, 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02173.x (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox M. J. et al. Airway microbiota and pathogen abundance in age-stratified cystic fibrosis patients. PLoS One 5, e11044, 10.1371/journal.pone.0011044 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels T. W. et al. Impact of antibiotic treatment for pulmonary exacerbations on bacterial diversity in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 12, 22–28, 10.1016/j.jcf.2012.05.008 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filkins L. M. et al. Prevalence of streptococci and increased polymicrobial diversity associated with cystic fibrosis patient stability. J Bacteriol 194, 4709–4717, 10.1128/JB.00566-12 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., Murray S. & Lipuma J. J. Modeling the impact of antibiotic exposure on human microbiota. Sci Rep 4, 4345, 10.1038/srep04345 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyczak J. B., Cannon C. L. & Pier G. B. Lung infections associated with cystic fibrosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 15, 194–222 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerem E. et al. Factors associated with FEV1 decline in cystic fibrosis: analysis of the ECFS Patient Registry. Eur Respir J 43, 125–133, 10.1183/09031936.00166412 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers G. B. et al. Clinical measures of disease in adult non-CF bronchiectasis correlate with airway microbiota composition. Thorax 68, 731–737, 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-203105 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razvi S. et al. Respiratory microbiology of patients with cystic fibrosis in the United States, 1995 to 2005. Chest 136, 1554–1560, 10.1378/chest.09-0132 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-On O. et al. Increasing nontuberculous mycobacteria infection in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros , 10.1016/j.jcf.2014.05.008 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J. et al. Impact of enhanced Staphylococcus DNA extraction on microbial community measures in cystic fibrosis sputum. PLoS One 7, e33127, 10.1371/journal.pone.0033127 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadkarni M. A., Martin F. E., Jacques N. A. & Hunter N. Determination of bacterial load by real-time PCR using a broad-range (universal) probe and primers set. Microbiology 148, 257–266 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maughan H. et al. Analysis of the cystic fibrosis lung microbiota via serial Illumina sequencing of bacterial 16S rRNA hypervariable regions. PLoS One 7, e45791, 10.1371/journal.pone.0045791 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods 7, 335–336, 10.1038/nmeth.f.303 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26, 2460–2461, 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F. et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 25, 3389–3402 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters V. et al. Chronic Stenotrophomonas maltophilia infection and exacerbation outcomes in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 11, 8–13, 10.1016/j.jcf.2011.07.008 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quanjer P. H. et al. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3-95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J 40, 1324–1343, 10.1183/09031936.00080312 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal K. M. & Cole T. J. Construction of LMS parameters for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts. Natl Health Stat Report 63, 1–3 (2013). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright C. M., Parker L., Lamont D. & Craft A. W. Implications of childhood obesity for adult health: findings from thousand families cohort study. BMJ 323, 1280–1284 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]