Abstract

In recent years, microRNAs or miRNAs have been proposed to target neuronal mRNAs localized near the synapse, exerting a pivotal role in modulating local protein synthesis, and presumably affecting adaptive mechanisms such as synaptic plasticity. In the present study we have characterized the distribution of miRNAs in five regions of the adult mammalian brain and compared the relative abundance between total fractions and purified synaptoneurosomes (SN), using three different methodologies.

The results show selective enrichment or depletion of some miRNAs when comparing total versus SN fractions. These miRNAs were different for each brain region explored. Changes in distribution could not be attributed to simple diffusion or to a targeting sequence inside the miRNAs. In silico analysis suggest that the differences in distribution may be related to the preferential concentration of synaptically localized mRNA targeted by the miRNAs. These results favor a model of co-transport of the miRNA-mRNA complex to the synapse, although further studies are required to validate this hypothesis.

Using an in vivo model for increasing excitatory activity in the cortex and the hippocampus indicates that the distribution of some miRNAs can be modulated by enhanced neuronal (epileptogenic) activity. All these results demonstrate the dynamic modulation in the local distribution of miRNAs from the adult brain, which may play key roles in controlling localized protein synthesis at the synapse.

1. Introduction

Translation of synaptically localized mRNAs is critical for neuronal processes such as synaptic plasticity, learning and memory [(Skup, 2008), (Sutton and Schuman, 2006)]. However, both timing and space constraining of such process seem to be key variables that may be fine-tuned by synaptic miRNAs [(Kosik, 2006), (Schratt, 2009)] given their ability to selectively down-regulate partially complementary target mRNAs [(Bhattacharyya et al., 2006), (Farh et al., 2005)].

Nearly 50% of all mammalian miRNAs are expressed in the brain [(Krichevsky et al., 2003; Lagos-Quintana et al., 2002; Sempere et al., 2004)] and many have critical roles in neurogenesis and neuronal development [(Giraldez et al., 2005), (Krichevsky et al., 2006)], yet their roles in the adult brain remain largely unexplored.

Many miRNAs not only show differential neuroanatomical expression [(Bak et al., 2008; Davis et al., 2007; Landgraf et al., 2007; Olsen et al., 2009)], but also display sub-cellular compartmentalization near the synapse [(Konecna et al., 2009), (Schratt, 2009)]. Several miRNAs have been found either enriched or depleted in laser-excised dendrites [(Kye et al., 2007)] and in synaptoneurosomal preparations [(Siegel et al., 2009)], with some pre-miRNAs enriched in the post-synaptic densities [(Lugli et al., 2008)]. Likewise, several partner proteins forming the miRNA silencing complex (miRISC) (i.e. Dicer, Argonaute 2 [(Lugli et al., 2005)], and FMRP [(Bassell and Warren, 2008), (Jin et al., 2004)] have been identified both pre- [(Hengst et al., 2006), (Murashov et al., 2007)] and post-synaptically [(Kye et al., 2007), (Lugli et al., 2008), (Feng et al., 1997; Fiore et al., 2009; Natera-Naranjo et al., 2010)].

It is well documented that neuronal stimulation may elicit an increase in protein synthesis (reviewed in [(Martin and Zukin, 2006), (Wu et al., 2007)]), but there is little evidence showing an effect on miRNA abundance. In some cases chemical or electrical induction of LTP/LTD [(Park and Tang, 2009), (Wibrand et al., 2010)], exposure to cocaine [(Chandrasekar and Dreyer, 2011)] and alcohol [(Wang et al., 2009)] may exert changes in miRNA expression and processing as well. In other cases, BDNF and NMDA also appear to reverse miRNA inhibitory activity over selective messenger RNA (mRNA) targets [(Kye et al., 2007), (Banerjee et al., 2009)].

Despite this, evidence for the involvement of miRNA activity in learning and memory has been provided only in invertebrates such as Drosophila [(Ashraf et al., 2006)] and Aplysia [(Rajasethupathy et al., 2009)], such results suggest that synaptic miRNAs act as key regulators of synaptic efficacy. However, the identity, regional and temporal abundance of synaptically localized miRNAs has not been fully established in the mammalian brain, much less their local regulation.

Here, we characterized synaptoneurosomal (SN) miRNAs based on their sequence and relative abundance across several regions of the mammalian brain. Furthermore, we explored the effect of prolonged excitatory stimulation over synaptic miRNA abundance in the cortex and hippocampus, after acute kainic acid (KA) administration, in a model well known to exhibit extensive synaptic plasticity [(Vincent and Mulle, 2009)]. Our findings demonstrate that miRNAs are differentially expressed at the neuroanatomical and sub-cellular levels, and that their local (synaptic) content is rapidly and selectively modulated during epileptogenic activity in vivo.

2. Results

2.1 Detection of miRNAs in synaptoneurosomes from total forebrain

We analyzed the mRNA and protein content from synaptoneurosomes (SN) extracted from the forebrain (Ce) of adult male rats (without olfactory bulb), following a method that allows enrichment of post-synaptic densities (PSDs; Supplemental Figure 1A). SN fractions (SCe) exhibited a good integrity of synaptic structures, as judged by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), accompanied by significant absence of nuclear and soma-related proteins (Supplemental Figure 1B-E). Interestingly several components of the miRISC machinery were abundant in this fraction, including Ago family and FMRP proteins (Supplemental Figure 1C). This finding is in agreement with recent observations showing enrichment of Dicer and other miRSC proteins in postsynaptic densities (Lugli et al., 2005).

Likewise, the recovered RNA from all SN fractions showed good integrity (Supplemental Figure 2A) and qPCR analysis of SCe fractions revealed low abundance of soma-enriched mRNA markers such as ArhGEF5 or Tubα1 (Supplemental Figure 2B), which was accompanied by a significant expression of NMDAR1 and PSD-95 synaptic mRNAs (Supplemental Figure 2C). We could not detect signal amplification in the SN fraction of low molecular weight non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), like the nucleolar marker snoRNA U43, indicating low contamination of soma or nuclear components in our SN fraction (Supplemental Figure 2D-E).

In order to determine the number and abundance of miRNAs from the forebrain, we probed 258 miRNAs (miRBase v9.0 [(Griffiths-Jones, 2006; Griffiths-Jones et al., 2006)]) on several microarrays arranged in a loop design, alternating Total and SCe samples following dye-swap labeling with Cy3 and Cy5 fluorophores (see Materials and Methods). We use swapping to reduce the effects of differential labeling on the results obtained.

To determine the relative abundance of these miRNAs on SCe, we used two methods of analysis, one to globally assess the number of miRNAs expressed in each sample (3SD), and the other with higher statistical stringency (MAANOVA), capable of disregarding technical effects (i. e. dye labeling efficiency, differential background intensity, or chip-to-chip variability) that commonly bias expression estimation in microarray experiments.

First we selected three standard deviations (3SD) above the average fluorescent signal intensity observed on negative control probes, as upper limit to consider any miRNA as truly expressed. Using this protocol we identified 141 miRNAs in Ce with no sample or labeling bias (Supplemental Figure 3A). These miRNAs accounted for nearly 55% of all 258 miRNAs probed in our platform. These miRNAs have been previously identified as neuronal miRNAs in mammals ([(Lagos-Quintana et al., 2002), (Bak et al., 2008; Landgraf et al., 2007)]). Nearly 98% of them were also found in SCe, although showing variable degrees of abundance as compared to Ce.

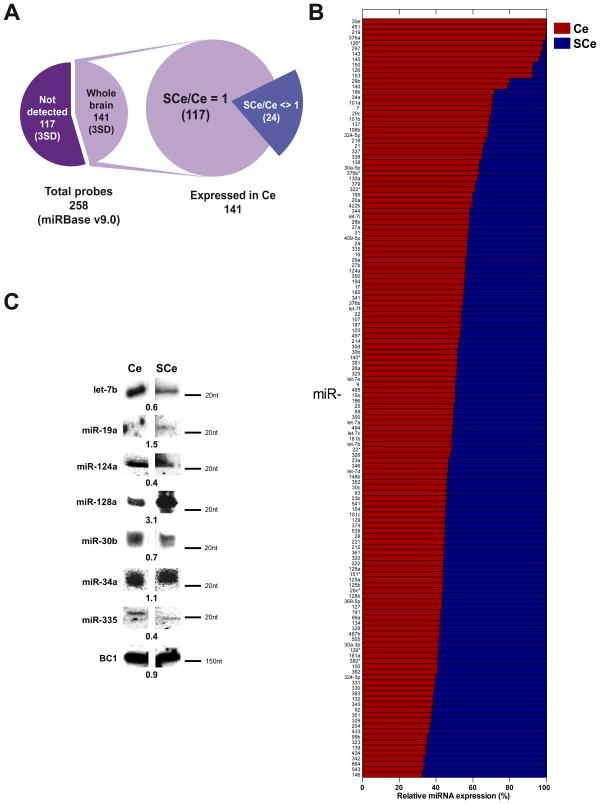

Based on the relative percentage expression ratio SCe/Ce (named PS/T, see Materials and Methods), two subsets of miRNAs were identified (Figure 1A). One contained 117 miRNAs expressed almost equally between both fractions (Supplemental 3B, see 3SD distribution, grey dots). The second subset contained 24 miRNAs that displayed significant differences between each fraction, either up- or down regulated in SCe (P≤0.05) (Supplemental Figure 3B). This pattern of differential expression remained similar across several sub-structures of the brain.

Figure 1. Expression analysis of synaptoneurosomal microRNAs from the whole brain of the adult rat.

(A) Pie diagram illustrating the 141 microRNAs found in the adult rat brain from the 258 explored (miRBase v9.0). (B) Percentage Ce/SCe miRNAs expression for the 141 found in the rat brain. (C) Identification of some of the most abundant matures miRNAs by Northern Blot (NB). Numbers shown below illustrate the ratio Ce/SCe from densitometry analysis. The non-coding RNA BC1 is used as control.

Such observations were corroborated by northern blot analysis (NB) for several highly expressed miRNAs (Figure 1C). We decided to test only highly expressed miRNAs given the lower sensitivity of the NB when compared to microarray or qPCR. Nevertheless, not all mature miRNAs tested were detectable with this method (Figure 1C). This was the case for miR-145 and miR-150, yet in the latter we observed two bands between 80 to 100 nt long (Supplemental Figure 4D). Since mature miRNAs are contained within the pre-miRNA sequences, methods such microarrays and qPCR cannot distinguish between both structures, whereas NB can identify both of them based on the migration pattern in the electrophoresis. This is the reason we considered relevant to study several abundant miRNAs with NB.

In order to verify the expression differences between the total and SN fractions detected by microarray, we used the same RNA as input in real-time qPCR for 21 candidate miRNAs. We selected these candidates based on our stringent MAANOVA method (Table 1A).

Table 1A. Relative expression of miRNAs from Ce and SCe selected by MAANOVA.

Relative abundance is represented as the ratio SCe/Ce for significant miRNAs expressed in the whole brain.

| miRNA | Microarray (SN/Total) |

|---|---|

| miR-347 | 1.36 |

| miR-434 | 1.36 |

| miR-342 | 1.35 |

| miR-92 | 1.35 |

| miR-92b | 1.32 |

| miR-146 | 1.32 |

| miR-323 | 1.31 |

| miR-327 | 1.31 |

| miR-204 | 1.30 |

| miR-329 | 1.29 |

| miR-132 | 1.28 |

| miR-142-5p | 1.26 |

| miR-339 | 1.25 |

| miR-344 | 1.25 |

| miR-139 | 1.24 |

| miR-485 | 1.23 |

| miR-99b | 1.23 |

| miR-146b | 1.21 |

| miR-331 | 1.19 |

| miR-382 | 1.19 |

| miR-184 | 1.19 |

| miR-495 | 1.18 |

| miR-338 | 1.18 |

| miR-487b | 1.17 |

| miR-181a | 1.17 |

| miR-652 | 1.17 |

| miR-30e* | 1.17 |

| miR-196a | 1.16 |

| miR-422b | 0.86 |

| miR-195 | 0.84 |

| miR-199a* | 0.81 |

| miR-705 | 0.78 |

| miR-466 | 0.77 |

| miR-265 | 0.75 |

| miR-352 | 0.72 |

| miR-467a | 0.64 |

| miR-467b | 0.60 |

| miR-685 | 0.51 |

| miR-690 | 0.42 |

| miR-650 | 0.42 |

| miR-154 | 0.39 |

| miR-151* | 0.35 |

| miR-129 | 0.35 |

| miR-150 | 0.35 |

| miR-709 | 0.34 |

| miR-126 | 0.33 |

| miR-145 | 0.33 |

| miR-143 | 0.08 |

As expected, after comparing SN/Total ratios from microarray and real-time qPCR data, all six significant miRNAs positively correlated between both methods, although with slight differences in magnitude (Supplemental figure 5 and Table 1B). In agreement with microarray data, qPCR showed that several miRNAs, such as miR-143 and miR-145 were nearly absent in SCe (Supplemental figure 5).

Table 1B. qPCR validation of highly enriched or depleted miRNAs in synaptoneurosomes from the whole brain.

Six candidates were selected for qPCR after MAANOVA. Note that relative enrichment resulted higher in the qPCR assays likely due to the sensitivity of the method. P values represent significant statistical differences calculated by paired Student's t test (n=3).

| miRNA | Microarray (SN/Total) | qPCR (SN/Total) | P-val (qPCR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-434 | 1.36 | 2.5±0.17 | 5.00×10-4 |

| miR-132 | 1.28 | 2.29±0.48 | 8.30×10-2 |

| miR-181a | 1.17 | 2.14±0.17 | 5.40×10-2 |

| miR-126 | 0.33 | 0.06±0.01 | 2.24×10-7 |

| miR-145 | 0.33 | 0.06±0.06 | 3.25×10-7 |

| miR-143 | 0.08 | 0.05±0.01 | 8.86×10-6 |

These results indicate that miRNA abundance in SN has a selectivity component, which does not necessarily depends upon the level of expression observed in the total fraction (containing mainly cell bodies and glia).

2.2 Identification of synaptic microRNA expression patterns by brain region

Several groups have demonstrated that miRNAs are differentially expressed across the brain [(Bak et al., 2008; Landgraf et al., 2007; Olsen et al., 2009)]. However, to this date there is no evidence suggesting that both the type and levels of expression also show a regional correlation for synaptically localized miRNAs. We explored whether the expression pattern of each region was maintained at the synaptic level across five major regions of the brain: olfactory bulb (Ob), cortex (Cx), hippocampus (Hp), cerebellum (Cb), and brain stem (Bs). We will be referring henceforward to each SN fraction with a capital “S” next to the name of their total homogenate fraction.

We used the same microarray loop design model, alternating dye-swapped samples to test for the highest consistency of miRNA expression across biological replicates. Data showed good linearity, with no major sample and labeling bias (Supplemental Figure 6A). miRNAs not detected in the total fraction were excluded from this analysis.

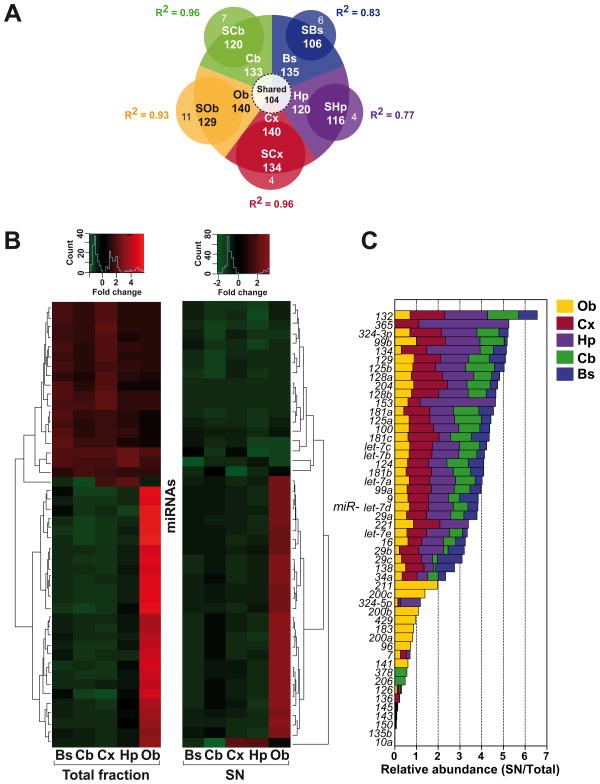

On average, synaptoneurosomal miRNAs from all regions accounted for over 50% of all probed rat miRNAs, as shown for Ce. We found that 140 miRNAs were expressed in Ob, 140 in Cx, 120 in the Hp, 133 in Cb, and 135 in Bs (Figure 2A), meanwhile their respective SN fractions had 129 miRNAs in SOb, 134 in SCx, 116 in SHp, 120 in SCb, and 106 in SBs (Figure 2A and Supplemental Table 1). From these, only 104 miRNAs showed common expression across all tissues, while only a reduced number were tissue-specific (Figure 2B-C). For example miR-183, miR-200, miR-200a, miR-200b, miR-211 and miR-429 were exclusively and strongly expressed in the olfactory bulb (Figure 2C). Others like miR-206 and miR-378 were selectively and strongly expressed in the cerebellum (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Differential expression patterns of synaptoneurosomal microRNAs derived from five neuroanatomical regions of the brain.

(A) Pie diagram illustrating the exclusively expressed and shared microRNAs in the five different areas of the brain explored. Areas are: Olfactory bulb (Ob), Cerebellum (Cb), Hippocampus (Hp), Cortex (Cx) and Brain stem (Bs). In all cases the capital S before the names indicate the respective synaptoneurosomal fraction. The Pearson's coefficients (R2) for the number of miRNAs expressed by fraction are indicated for each brain region. (B) Heatmap plotting of the 49 microRNAs selected by MAANOVA (P≤0.1) 54 miRNAs with consistent expression across all samples from the different regions explored in the rat brain. MiRNAs were hierarchically clustered and plotted as a heatmap. (C) Plotting of the same miRNAs by relative abundance (SN/Total) separated by areas of the brain. Notice that some miRNAs are selective for the olfactory bulb (Ob, in yellow) such as miR-211 and 200c, while others are exclusive for the cerebellum (Cb, in green) such as miR-378 and 206.

In all structures studied, we identified the same two groups of miRNAs based on their distribution between total and SN fractions. A first group of miRNAs with equal expression between total and SN, and a second group with miRNAs that were either more or less abundant in SN when compared to total.

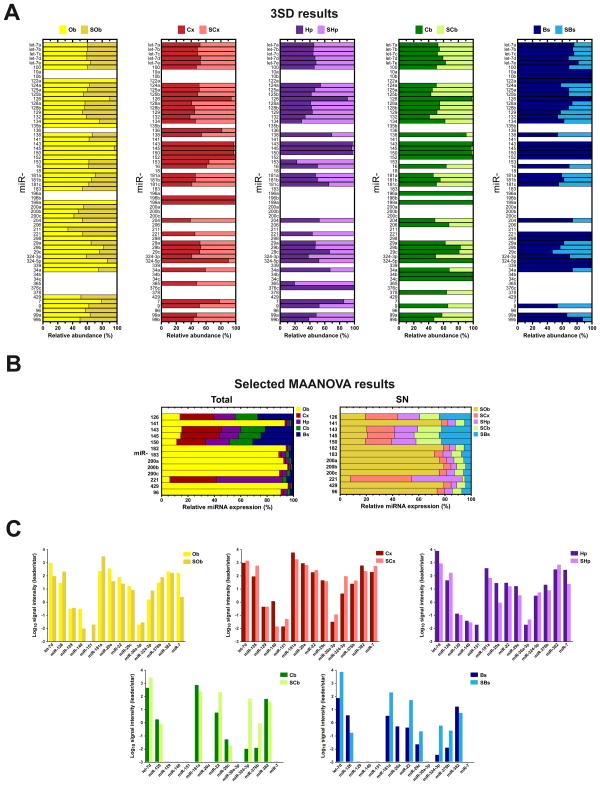

Interestingly, the number and relative abundance of synaptic miRNAs varied according to the tissue type (Figure 3A). For instance, nearly 97% of miRNAs expressed in the hippocampus were also present in its SN fraction, and their relative expression levels were more prominent in SN as compared to other tissues. For instance, miR-365 was very abundant in SHp, but found in the same proportion between Cx and SCx, and absent in Ob, Cb and Bs (Figure 3A). On the other hand, miR-152 was present in all total fractions (with the exception of Hp), but almost absent in their SN counterparts (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Relative expression and differential processing of miRNAs derived from distinct areas of the brain and their synaptoneurosomal fractions.

(A) Normalized expression of total homogenate SN fraction of 62 miRNAs (3SD results) arbitrarily selected by relevance with previously published data for comparison purposes. Data was computed taking as 100% the total sum of normalized fluorescence intensity mean for SN and total. (B) Normalized expression of miRNAs selected by MAANOVA analysis. Length of the bar is calibrated to 100% after summation of miRNA expression values observed by tissue sample. These miRNAs showed consistent expression across all tissues analyzed, for both SN and total fractions. (C) Differential processing of leader and star strands of miRNAs whose precursor gives rise to stable mature sequences (∼21nt), which have different abundances according to the tissue of origin. Bars represent the ratio leader/star of signal intensity observed in the microarray data in both fractions. All values were expressed in Log10 scale.

In fact, five miRNAs showed enrichment of more than three-fold in SHp but only two miRNAs were enriched in SOb, as opposed to what it was found in SCe with almost no miRNA expressed more than two-fold in average (Figure 3B). Finally, only the brain stem displayed the lowest number of synaptically enriched miRNAs (∼79%). The functional significance of this interesting observation remains to be explored.

Since precursor miRNAs (pre-miRs) may contained one or two mature miRNAs inside the precursor, and because very little is known about how precursors are processed in the brain, we decided to conduct experiments to determine if there was selective maturation in the SN fractions reflected as differential amounts of the leader or the star sequences from selected miRNAs. Figure 3C illustrates the ratio leader/star for several miRNAs previously identified in the five regions of the brain explored. This analysis yielded very interesting results, for instance, miR-151 star was very abundant in SOb but absent in Ob (Figure 3C). The opposite was observed in the Hp, where the same miR-151 star was very abundant, but absent in SHp. In general, for all miRNAs explored, we observed differential presence of leader and star sequences in total and SN fractions. These results indicate selective processing and maturation of pre-miRNAs. Although with these experiments we cannot determine if the processing is taking place in situ (the synapse), is worth mentioning that recent studies have identified Dicer (the protein responsible for pre-miRNA maturation) enriched at postsynaptic densities (Lugli et al., 2005).

Another interesting observation was that several paralogous miRNAs were differentially expressed throughout the brain. For instance miR-34b and miR-34c were expressed almost exclusively in the cerebellum, although with low levels in its SN fraction (Figure 3A). In spite of the remarkably high sequence identity with miR-34a (85.1% identity), only the later displayed a wider distribution throughout all tissues, especially in the brain stem where its abundance was almost two-fold as much as in Cb and SCb (Figure 3A).

This remarkable differential localization for SN-enriched miRNAs across brain regions could not be explained by a consensus signal inside the miRNAs. Sequence alignment of twenty miRNAs from each region, whose SN/Total ratio appeared in the top-most or in the bottom-least list of relative expression in SN, did not return a clearly identifiable consensus signal or tract that may explain its synaptic distribution. This analysis strongly suggest that heterogeneity might be related to other regulatory mechanisms, such as mRNA target association and transport to the synapse (Supplemental Figure 7).

We conducted Northern Blot (NB) analysis of several miRNAs in order to identify the relative abundance of pre-miRNAs and mature miRNAs. NB results showed good correlation with microarray and qPCR data, although not with the same magnitudes (Compare Supplemental Figures 4 and 5). This result was somewhat expected due to differences in sensitivity and selectivity in these methods.

It was remarkable that migrating bands with expected sizes for their pre-miRNAs (between 60 to 150nt) showed significantly more abundance than the mature fragments when inspecting mature/precursor band density ratios (see pixel intensity plots in Supplemental Figure 4B-D and hairpin structures in the far right side). Moreover, the relative abundance ratios also displayed some degree of heterogeneity between total and SN fractions, suggesting local differential miRNAs processing (see central panels in Supplemental Figure 5B-D). Differential synaptic accumulation of miRNAs in their precursor (pre-miRNAs) and/or mature forms can be explained by the fact that the processing machinery for miRNA maturation has been recently identified in the synapse, and its function is modulated by neuronal activity (Lugli et al., 2005).

To explore whether the synaptic enrichment of selective miRNAs correlates with an increased probability of finding their mRNA targets at that location, we used the miRanda algorithm ([(Betel et al., 2008)]; August 2010 release) to obtain a list of potential miRNAs targets. We filtered genes with known Gene Ontology (GO) tags, including categories of cellular component (419), biological (628), and molecular function (597), and then compared this list against the rat genome as reference, using the FatiGO tool [(Al-Shahrour et al., 2004)]. As expected, enrichment of these genes changed slightly depending upon the tissue analyzed (Supplemental Figure 8A), and the number and type of mRNA-coding genes found were differentially distributed as per neuroanatomical region. We found that most predicted targets belong to genes associated with neuronal function, including proteins located at the post-synaptic level, others involved in processes like synaptic plasticity, learning and memory, and some mediators of short-term adaptive mechanisms (Supplemental Figure 8A-B). This finding suggests that most of the miRNAs found in our SN preparations likely help in the regulation of many specialized local mechanisms, either at the pre- or post-synaptic levels.

In summary, we found that each brain region explored displays a specific pattern of synaptic miRNAs content, distinct from that seen in the forebrain and even in their respective total fractions. Such selective distribution cannot be attributed to a specific sequence inside the miRNA, but may be explained by other mechanisms, such as the association of the miRNA to its mRNA target and subsequent selective transport of both to the synapse, among other possibilities.

2.3 Synaptic miRNA expression in kainic acid treated animals

Given the differential distribution of many miRNAs in all brain regions explored, and in particular the enrichment of some miRNAs in our SN preparations, we wanted to explored if such relative accumulation was constant or could be modulated by neuronal activity.

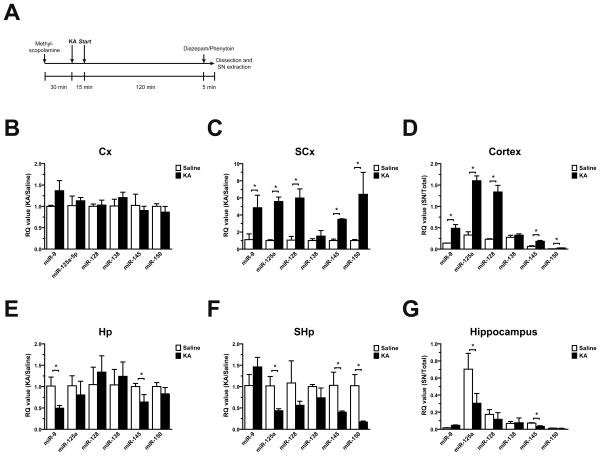

Since it is known that neuronal activity may alter the translational rate especially in dendrites (reviewed in [(Schratt, 2009), (Steward and Reeves, 1988)]), we explored if neuronal stimulation might elicit changes in the abundance of synaptic miRNAs as well. To test this hypothesis we used systemic kainic acid (KA) to induce seizure activity in the brain of living animals for two hours (Figure 4A) as model for sustained neuronal depolarization in vivo, especially in the hippocampus and cortex given the high abundance of high affinity KA ionotropic receptors. After treatment, total RNA prepared from total homogenate and SN fractions from Cx and Hp was used for NB and qPCR analysis. Based on the level of expression previously observed for several miRNAs, we selected six candidates with robust expression in SN from those two areas (miR-9, miR-125a-5p, miR-128, and miR-138), and two others that were significantly depleted (miR-145 and miR-150) to asses the effect of exacerbated neuronal activity on the relative distribution of each miRNA.

Figure 4. KA treatment modifies the synaptoneurosomal expression of cortical and hippocampal miRNAs in vivo.

(A) Schematized protocol of KA treatment used for seizure induction. Cortical (Cx) and hippocampal (Hp) miRNA expression was assessed by qPCR on either (panels B-E) the total homogenate, or (panels C-F) the SN fractions. As input, 200 ng of total RNA from three animals from each group was used as template for reverse transcription. The SN/Total ratio of miRNA expression in Cx (D) and Hp (G) reflect variable abundances of the measured miRNAs. Significant differences were calculated by a two-tailed Student's t-test analysis for paired samples (asterisks; P≤0.01).

The qPCR analysis demonstrated that seizure-induced animals showed no significant change in expression in both Cx and Hp (Figure 4B), except for miR-9, which was down regulated nearly 50% and miR-145 which showed a small but significant reduction in Hp (Figure 4E).

When analyzing the SCx fraction we observed an average 5 fold increment for all miRNAs tested, with the exception of miR-138, which remained unaltered after the treatment (Figure 4C). Most surprisingly all miRNAs but miR-9 and miR-138, were reduced in SHp (Figure 4F). In particular, miR-150 was reduced almost 5 fold when compared to control (saline) treatment (Figure 4F).

Since most miRNAs explored were unaltered in the total (Cx and Hp) fractions (Figure 4B-E). This result suggests a selective modulation of their relative concentrations at the synapse upon exacerbated neuronal activity in vivo. This observation was more evident when analyzing the SN/Total ratio for the miRNAs explored (Figure 4D-G).

These findings were confirmed by NB analysis for miR-128 and miR-125a-5p, although changes in the mature sequence (∼21nt) showed different magnitudes (Supplemental Figure 9A-E). However, a close look at the precursors bands of miR-9, miR-125a-5p and miR-150 indicated that the relative abundance of each changed proportionally as well (Supplemental Figure 9B to J), suggesting that sustained electric depolarization in vivo might also affect pre-miRNA processing within the synapse.

We concluded that the short-term effect of KA treatment on miRNA expression in this model is highly selective and tissue-specific. Most importantly, it seems that this treatment predominantly induces changes in miRNAs selectively at the synapse, rather than altering their abundance in the rest of the neuron. Most interestingly, only a handful of miRNAs changed their local concentration, with others showing no change with KA treatment.

3. Discussion

In the present study we carried out an extensive characterization of the miRNAs present in five regions of the mammalian brain. We attempted also to determine the relative concentration of such miRNAs between total and SN fractions for each of the regions explored. The method we utilized allowed us to enrich the SN fraction with post-synaptic densities (PSDs), as confirmed by the TEM analysis (Supplemental Figure 1B). Nevertheless, we acknowledge that 100% pure SN fractions are extremely difficult to obtain, since several contaminants may co-sediment (cytosol from the cell-body, mitochondria, or glia). However, the lack of glial markers (GFAP or MBP proteins; Supplemental Figure 1C to E), or the significant reduction (∼85%) of nuclear- and soma-restricted mRNA and ncRNA markers (snoRNA U43, NeuN, ArhGEF5, ArhGEF11, Tubα1, or Tubα3; Supplemental Figure 2B-D), indicates that that we have a reasonably pure SN preparation from which conclusions about relative miRNAs distribution can be drawn. Moreover, expression of several miRNAs previously identified in mitochondria [(Kren et al., 2009; Li et al., 2011)] was very low in our preparations, as determined by the microarray data. Unlike previous reports [(Schratt, 2009)], we still detected a small contribution of U6 snoRNA in SN (Supplemental Figure 2B); however we believe that this does not necessarily reflect nuclear contamination, but rather it may support the observation of spliceosomal activity in dendrites [(Glanzer et al., 2005)] or another function specific to this ncRNA, although this deserves further scrutiny.

As for the relative abundance of synaptic miRNAs it was interesting to find that many of them did not depict a significant enrichment in SN (>2-fold), in contrast to former observations [(Lugli et al., 2008; Siegel et al., 2009)]. We believe that this does not necessarily correspond to suboptimal SN isolation but rather to actual properties of components more tightly associated to the post-synaptic densities, considering the abundance of several synaptic protein and mRNA markers, like NMDAR1, PSD-95 and the ncRNA BC1, whose abundance was approximately 90% the one seen in the total fraction (see Supplemental Figure 2C-4B).

Furthermore, the relative abundance of sixteen miRNAs observed in our SN fractions are also comparable to those described in laser-excised dendrites of cultured hippocampal neurons or by ISH [(Kye et al., 2007), (Pena et al., 2009)], supporting that these miRNAs also display a similar somato-dendritic expression in the adult rat brain as well.

The relative enrichment of miRNAs in our SN preparation, cannot be explained by simple diffusion from the soma, and may be the result of active transport. In this regard, some authors have proposed that somato-dendritic translocation of miRNAs may comprise several hypotheses, all-non mutually exclusive [(Kosik, 2006; Schratt, 2009)]. Some include the co-transport of mature miRNAs along with their mRNA targets as part of neuronal granules cargo and the selective pre-miRNA translocation by attachment to tagged dendritic proteins that are actively translocated to the synaptic contacts vicinity (i.e. FMRP family).

In the present study we did not attempt to demonstrate a particular mechanism, but our data do not support the simple diffusion hypothesis as a main source for synaptic localization, given that several miRNAs with elevated expression values in the total fraction were not found among the most highly expressed miRNAs in the SN.

Our in silico analysis did not find any consensus sequence or signal that may explain synaptic enrichment of miRNAs (Supplemental figure 7), thus suggesting that the mechanism may not involve a targeting sequence.

A feasible mechanism for synaptic translocation may involve association of the miRNAs to their mRNA targets, functioning as passive cargo of dendritically localized mRNAs. The latter idea might be supported by the finding that i) the sequence analysis of the most abundant miRNAs in SN lacked an obvious consensus signal that could describe a dendritic localization motif (Supplemental figure 7), and ii) our analysis to identify putative mRNA targets shows that such possible targets produce proteins with functions tightly associated with synapse activity (Supplemental Figure 8), and in fact, many of them have already been found in isolated PSD-rich SN in the rodent brain [(Suzuki et al., 2007)].

One interesting aspect of current research is the question of whether miRNAs we detected in SN belong to the pre- or the post-synaptic compartments. It is now becomingly accepted that in the adult CNS axons may display protein synthesis activity, independently from the cell soma [(Giuditta et al., 2008)], which also appear to co-exist with RNAi activity, as documented in several systems, including the adult peripheral nerve endings [(Murashov et al., 2007)], and in the developing growth cones of cultured hippocampal neurons, where RISC proteins Ago2, FMRP, Gemin3 helicase and p100 nuclease had been identified as well [(Hengst et al., 2006)].

Even though the expression of miRNAs showed neuroanatomical specificity, as previously documented [(Bak et al., 2008; Lugli et al., 2008; Olsen et al., 2009)], we found that not all miRNAs obeyed the same distribution in their SN fractions. For instance, the hippocampus and cortex displayed more miRNAs with higher abundance in SN than any other region analyzed here (Figure 2A), even more than the cerebellum, which has significantly higher number of synapses per neuron than any other brain structure.

Interestingly, we found that several pre-miRNAs were highly enriched in the SN fraction as well, as it was the case for miR-9, miR-125a-5p and miR-150. Since recent studies have identified the presence of Dicer and RISC members at the synapse (Lugli et al., 2005; Lugli et al., 2008), it is feasible that some local miRNA processing may take place. This hypothesis deserves future studies.

Summarizing, in the present work we demonstrated not only that mammalian miRNAs are synaptic constituents, but also that they have a differential distribution across the brain regions explored. Moreover, some of these miRNAs undergo local regulation of their abundance within the synapse, following exacerbated neuronal activity in vivo. These findings show for the first time local modulation of the concentration of selective miRNAs by in vivo epileptogenic activity, indicating that the relative miRNA abundance at the synapse may be dynamically modulated.

4. Experimental Procedures

4.1 Animals

Three months-old adult male Long-Evans (LE) rats weighing ∼200 g were anesthetized with isoflurane (5% v/v) and sacrificed by decapitation, following protocols for animal care approved by the Animal Care Committee from Rutgers University. Brains were washed in ice-cold, nuclease-free PBS, and dissected on ice with RNAse Zap-treated tools (Ambion/Applied Biosystems, Austin, TX USA). On average, hippocampi and cortices from each hemisphere were obtained in less than six minutes per animal to minimize RNA degradation.

4.2 Synaptoneurosomes isolation

Pure synaptoneurosomal fractions were obtained by differential isopycnic centrifugation (modified from [(Carlin et al., 1980)]) through sucrose gradients. Approximately 1 g of tissue from three animals (either forebrain, olfactory bulb, cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum or brain stem) was placed in a motorized Teflon/glass homogenizer (0.25 mm clearance space) and samples were processed by giving twelve strokes at medium speed in ice-cold Solution A (0.32 M sucrose plus 1 mM NaHCO3, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 25 U/mL RNase OUT (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA. USA.), and 1% Halt proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Pierce-ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA USA). At this stage one aliquot was removed (named Total Fraction) for protein and RNA analysis. The homogenate was centrifuged twice for 10 min at 1,400 × g in a JA-17 rotor (Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA USA) to separate cell nuclei and debris (fraction P1), and the supernatant (S1) was further centrifuged for 10 min at 13, 800 × g. The resulting pellet was re-suspended (S2) in 2 mL of Solution B (0.32M sucrose plus 1 mM NaHCO3) and poured onto a buffered discontinuous sucrose gradient (from top to bottom, 0.32 M/0.85 M/1 M/1.2 M), containing 1 mM NaHCO3 (pH 7.2), and ultra-centrifuged at 82,500 × g in a SW40-Ti rotor (Beckman). The interface band between layers 1 M and 1.2 M (synaptoneurosomal fraction) was removed and adjusted to 3-4 mL with Solution B, then layered onto a 1 M sucrose cushion, and centrifuged again at 82,500 × g for 1 h. Samples from the upper interfacial bands, namely myelin and microsomes, were analyzed for protein content as well. Pellets from this step were re-suspended in nuclease-free ice-cold PBS. All steps were carried out at 4°C.

4.3 RNA extraction and quantification

RNA from both total and synaptoneurosomal fractions were extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's guidelines, except that at least 2/3 volumes of isopropanol and 10-15 μg of linear acrylamide were used for precipitating RNA, and 80% ethanol was used for washing the resulting pellet. Resulting samples were re-suspended in nuclease-free water and quantified in a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA USA). Quality of RNA was assessed by using a Bioanalyzer (Agilent Labs, Santa Clara, CA USA).

4.4 Microarray labeling and hybridization

The multi-species NCode™ microarray platform chip v2.0 from Invitrogen, containing all miRNA probes released in miRBase v9.0, was used for this study. For the total brain (Ce) and its synaptoneurosomal fraction (SCe) experiment, 2 μg of total RNA from three different animals was labeled either with Cy3 or Cy5 fluorophores with a FlashTag™ T4 RNA ligase-based method (Genisphere, Hatfield, PA USA). To compensate for dye labeling efficiency and sample bias, six chips were used. We applied loop design on two-channel arrays, dye-swapping biological replicates. For the brain regions array analysis, both total and synaptoneurosomal RNA samples from olfactory bulb (OB), cortex (Cx), hippocampus (Hp), cerebellum (Cb), and brain stem (BS) were taken from three animals, and samples from the same tissue were pooled together. For this analysis we applied the same design as above, using ten chips.

4.5 Microarray statistical analysis

The Bioconductor limma and MAANOVA packages from R/Bioconductor (www.bioconductor.org) was used for linear fitting and statistical comparisons, respectively. Data were analyzed by bootstrapping F-statistics [(Altman and Hua, 2006,Altman and Hua, 2006; Kerr and Churchill, 2001a; Kerr and Churchill, 2001b)], re-fit with or without VG effects and new F-values were calculated and compared to original calculation. P-values represent the probability of obtaining higher F-statistics values after comparing data against 10,000 random permutations. Results were adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction. Significant miRNAs were selected on a P-value threshold of P<0.01 for F1 tests, and P<0.05 for F3 and Fs tests for Ce vs. SCe study and P<0.1 for F1 tests, and P<0.05 for F3 and Fs tests for multiple brain regions analysis.

4.6 mRNA and miRNA quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

For mRNA expression assessment we designed primers using Primer Express™ software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA. USA.) to obtain 100-mer amplicons for each gene. Reverse transcription was carried out by using random hexamer primers and SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). For qPCR we used SyBR Green™ buffer (Applied Biosystems). For miRNA expression measurements, we used either Taqman™ miRNA qPCR assays (Applied Biosystems) or NCode™ miRNA first strand cDNA synthesis and qPCR kits (Invitrogen) for miRNA reverse transcription and PCR amplification, following manufacturer's guidelines. All oligonucleotides used with the method from Invitrogen were custom-made and their sequence corresponded to the exact mature miRNA sense sequence. All assays were quantified in either an ABI 7500 Fast model or in an ABI 7900HT real-time PCR thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems). Data were analyzed with SDS v2.3 and RQ manager v1.2 software (Applied Biosystems). Averaged Delta Cycle threshold values (dCt) from three to six animals were independently compared between paired samples (Total vs. SN), and differences were analyzed by using the two-tailed Student's t-test for statistical validation. We computed the percentage of SN/Total value (PS/T) as the ratio [(2Ct of SN fraction/2Ct of Total fraction)(100)] to express of the amount of template retained in the SN fraction after isolation.

4.7 Seizure induction by kainic acid (KA) treatment

Male Long-Evans rats with the same age and weight as described before were pre-treated with methyl-scopolamine (1 mg/kg, s.c.; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO. USA) to inhibit peripheral convulsions, according to the animal care guidelines of the NIH and the local ethics committee. After 30 min, animals were injected with KA (10 mg/kg, i.p), or saline as a control. No noxious generalized myotonic-clonic events were observed after treatment with KA. After two hours, 10 mg/kg diazepam (Henry Schein, Melville, NY) and phenytoin (50 mg/kg, i.p., Sigma) were injected to stop seizure activity, and animals were immediately sacrificed by decapitation.

Additional Methods

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Synaptoneurosomal pellets were resuspended in PBS and fixed for 2 hrs in Karnovsky's Fixative (combination of low concentration of both formaldehyde and glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M Milloning's Phosphate buffer pH 7.3). Post-fixation was carried out in 1% Osmium Tetroxide buffer for 1h, followed by dehydration in graded ethanol series and embedded in Epon-Araldite cocktail. Sections were done using a diamond knife by LKB-2088 Ultramicrotome (LKB – Produkter AB, S-161 25 Bromma 1, Sweden). Thin sections were stained with 5% (w/v) uranyl acetate saturated solution in 50% ethanol for 15 min at room temperature, and then with 0.5% lead citrate solution in CO2-free double-distilled water (Reynold's Lead Citrate Stain) for 2 min. Observation and micrographs were made with a JEM-100CXII Electron Microscope. (JEOL LTD. Tokyo, Japan).

Western blot

Samples from all fractionation steps were collected and mixed with ice-cold lysis buffer (pH 7.5) containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1% (v/v) Nonidet P-40, 0.5% SDS, and 1% Halt protease inhibitor cocktail (ThermoScientific). Protein concentration was determined by the BCA method (Pierce-ThermoScientific). 10-25 mg of protein were used and analyzed by PAGE (4:12%) and proteins transferred to a PDVF membrane. All membranes were blocked with 1X PBS, containing 1% (v/v) Tween-20, and 10% non-fat milk for at least 2h at 4°C. Monoclonal antibodies used in this study were mouse anti- SV2 (clone SP2/0; 1:1,000) developed by Dr. Kathleen M. Buckley, Harvard Medical School, MA; rat anti-FMRP (clone 7G1-1; 1:500) developed by Dr. Stephen T. Warren, Emory University School of Medicine, GA; mouse anti-Tubulin-a1 (clone AA4.3; 1:1,000) developed by Dr. Charles Walsh, University of Pittsburgh, PA; mouse anti-Synaptotagmin (clone asv48; 1:500) developed by Dr. Louis Reichardt, UCSF, CA), all from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, IA; rabbit anti-TuJ1/tubulin-b3 (clone TUJ1 1-15-79 ;1:1,000) was obtained from Covance Inc.; mouse anti-Ago1-4 (clone 4F9; 1:1,000) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., (Santa Cruz, CA USA); mouse anti-b-actin (clone mAbcam 8226; 1:10,000) was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA USA.); mouse anti-NeuN (1:500) was from Chemicon (Millipore, Billerica, MA USA.); mouse anti-PSD-95 (clone 7E3-1B8; 1:2,000) was from Affinity Bioreagents Inc. (Rockford, IL USA.); and polyclonal antibodies were rabbit anti-NMDAR1 (1:1,000) was from Chemicon (cat. # ab5046p, Millipore); and rabbit anti-Ago2 (1:1,000) was from Upstate (cat. # 04-642, Millipore). All primary antibodies were diluted in 1X PBS (containing 1% (v/v) of Tween-20 plus 0.02% of NaN3), and incubated for 8-16 h at 4°C. Bands were revealed by ECL Plus chemiluminescent detection kit (Amersham-GE) using either anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies coupled to HRP (Amersham-GE, Piscataway, NJ. USA). Images were acquired on film (Hyperfilm ECL Amersham-GE), or by CCD camera (Gel Logic 2200 Image Station, Kodak Inc.).

Northern blot

Total RNA from all samples was column-purified and size-fractioned (<200 nt) by partial precipitation according to guidelines of the miRvana miRNA isolation kit (Ambion-Applied Biosystems, Austin, TX. USA). Denatured 0.5 to 1 μg of purified RNA (92°C, 2min) was resolved by PAGE (15%; 19:1; 8M Urea), samples were then transferred onto a positively charged nylon membrane (Amersham-GE, Buckinhamshire, England) on a semi-dry apparatus (Biorad, Hercules, CA. USA), UV-crosslinked, and pre-hybridized with 6X SSC, 10X Denhardt's buffer and 0.2% SDS (pH 7.2). Approximately 25-50 pmol of DNA (Sigma-Aldrich) or LNA probes complementary to the mature miRNA sequences (Exiqon, Vedbaek, Denmark) were labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase (Invitrogen), using 32P-γ-ATP as donor (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA. USA.), followed by sepharose G-25 or G-50 column purification (Amersham-GE Life Sciences). Hybridization was carried out for at least 8 h at 37-45°C (in average 12°C below the Tm of DNA probes, or Tm minus 25°C for LNA probes). All membranes were washed twice with 6X SSC/0.2% SDS, and exposed (3 to 8h) to an intensifying Phosphorimager screen and scanned on a Typhoon device (Amersham-GE Life Sciences). Most membranes were re-blotted up to five times following stripping (2X in 1% SDS at 95°C for 30min) with no significant loss of signal between blots. Densitometric analysis was carried out with NIH's ImageJ software (Rasband, W.S., 1997-2009).Table 1A - Relative expression of miRNAs from Ce and SCe selected by MAANOVA.

Relative abundance is represented as the ratio SCe/Ce for significant miRNAs expressed in the whole brain. Table 1B - qPCR validation of highly enriched or depleted miRNAs in synaptoneurosomes from the whole brain.

Six candidates were selected for qPCR after MAANOVA. Note that relative enrichment resulted higher in the qPCR assays likely due to the sensitivity of the method. P values represent significant statistical differences calculated by paired Student's t test (n=3).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the Hart lab for helpful discussions, technical assistance, and comments to the manuscript. Also, we thank Dr. Bonnie Firestein for help on SN preparations, Dr. Valentin Starovoytov for support on TEM studies, and the staff of the W. M. Keck Center for Collaborative Neuroscience at Rutgers University, NJ, USA. Support was provided by the New Jersey Stem Cell Commission, and Life Technologies Corp., USA. From the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), we thank Dr. Luis Padilla and Dr. Enrique Reynaud for valuable observations to the project. Also to Dr. Maria Sitges and Dr. Clorinda Arias for supplying pharmaceuticals, Dr. Rodolfo Paredes for TEM assistance, Alicia Sampieri, M.S. for technical support, and the staff of the animal care facility at the Instituto de Fisiología Celular (IFC). This project was supported in part by the Programa de Doctorado en Ciencias Biomédicas (PDCB, UNAM), Instituto de Ciencia y Tecnología del Distrito Federal (ICyTDF), and Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT) to LV.

Abbreviations

- miRNA

microRNA

- SN

synaptoneurosomes

- KA

kainic acid

- qPCR

quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- miRISC

miRNA-induced silencing complex

Footnotes

Authors' contributions: IPC carried out all experiments, except those on the microarrays, performed all subsequent analyses, prepared the manuscript draft and the figures contained therein. LAG performed the microarray experimental design, data acquisition and post hoc statistical analyses, and prepared some related figures. MRS carried out RNA labeling and hybridization on microarray experiments. MRB and JD made important observations on the manuscript draft. AA participated in the GO-enrichment analysis. WJF and MLV provided materials and expertise with the KA model. RPH made critical contributions to the project, critical reviews to the manuscript, provided materials and expertise with the qPCR and microarray platforms and on the public release of experimental results on the NIH GEO database. LV provided materials, participated in the design, discussion and general coordination of the experiments and wrote the manuscript in its final form. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Al-Shahrour F, Diaz-Uriarte R, Dopazo J. FatiGO: a web tool for finding significant associations of Gene Ontology terms with groups of genes. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:578–80. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman NS, Hua J. Extending the loop design for two-channel microarray experiments. Genet Res. 2006;88:153–63. doi: 10.1017/S0016672307008476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf SI, McLoon AL, Sclarsic SM, Kunes S. Synaptic protein synthesis associated with memory is regulated by the RISC pathway in Drosophila. Cell. 2006;124:191–205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bak M, Silahtaroglu A, Moller M, Christensen M, Rath MF, Skryabin B, Tommerup N, Kauppinen S. MicroRNA expression in the adult mouse central nervous system. RNA. 2008;14:432–44. doi: 10.1261/rna.783108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S, Neveu P, Kosik KS. A coordinated local translational control point at the synapse involving relief from silencing and MOV10 degradation. Neuron. 2009;64:871–84. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassell GJ, Warren ST. Fragile X syndrome: loss of local mRNA regulation alters synaptic development and function. Neuron. 2008;60:201–14. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betel D, Wilson M, Gabow A, Marks DS, Sander C. The microRNA org resource: targets and expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D149–53. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya SN, Habermacher R, Martine U, Closs EI, Filipowicz W. Relief of microRNA-mediated translational repression in human cells subjected to stress. Cell. 2006;125:1111–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlin RK, Grab DJ, Cohen RS, Siekevitz P. Isolation and characterization of postsynaptic densities from various brain regions: enrichment of different types of postsynaptic densities. J Cell Biol. 1980;86:831–45. doi: 10.1083/jcb.86.3.831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekar V, Dreyer JL. Regulation of MiR-124, Let-7d, and MiR-181a in the Accumbens Affects the Expression, Extinction, and Reinstatement of Cocaine-Induced Conditioned Place Preference. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:1149–64. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CJ, Bohnet SG, Meyerson JM, Krueger JM. Sleep loss changes microRNA levels in the brain: a possible mechanism for state-dependent translational regulation. Neurosci Lett. 2007;422:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farh KK, Grimson A, Jan C, Lewis BP, Johnston WK, Lim LP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. The widespread impact of mammalian MicroRNAs on mRNA repression and evolution. Science. 2005;310:1817–21. doi: 10.1126/science.1121158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Gutekunst CA, Eberhart DE, Yi H, Warren ST, Hersch SM. Fragile X mental retardation protein: nucleocytoplasmic shuttling and association with somatodendritic ribosomes. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1539–47. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-05-01539.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore R, Khudayberdiev S, Christensen M, Siegel G, Flavell SW, Kim TK, Greenberg ME, Schratt G. Mef2-mediated transcription of the miR379-410 cluster regulates activity-dependent dendritogenesis by fine-tuning Pumilio2 protein levels. EMBO J. 2009;28:697–710. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraldez AJ, Cinalli RM, Glasner ME, Enright AJ, Thomson JM, Baskerville S, Hammond SM, Bartel DP, Schier AF. MicroRNAs regulate brain morphogenesis in zebrafish. Science. 2005;308:833–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1109020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuditta A, Chun JT, Eyman M, Cefaliello C, Bruno AP, Crispino M. Local gene expression in axons and nerve endings: the glia-neuron unit. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:515–55. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00051.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanzer J, Miyashiro KY, Sul JY, Barrett L, Belt B, Haydon P, Eberwine J. RNA splicing capability of live neuronal dendrites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16859–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503783102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths-Jones S. miRBase: the microRNA sequence database. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;342:129–38. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-123-1:129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths-Jones S, Grocock RJ, van Dongen S, Bateman A, Enright AJ. miRBase: microRNA sequences, targets and gene nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D140–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengst U, Cox LJ, Macosko EZ, Jaffrey SR. Functional and selective RNA interference in developing axons and growth cones. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5727–32. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5229-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin P, Zarnescu DC, Ceman S, Nakamoto M, Mowrey J, Jongens TA, Nelson DL, Moses K, Warren ST. Biochemical and genetic interaction between the fragile X mental retardation protein and the microRNA pathway. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:113–7. doi: 10.1038/nn1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr MK, Churchill GA. Experimental design for gene expression microarrays. Biostatistics. 2001a;2:183–201. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/2.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr MK, Churchill GA. Statistical design and the analysis of gene expression microarray data. Genet Res. 2001b;77:123–8. doi: 10.1017/s0016672301005055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konecna A, Heraud JE, Schoderboeck L, Raposo AA, Kiebler MA. What are the roles of microRNAs at the mammalian synapse? Neurosci Lett. 2009;466:63–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosik KS. The neuronal microRNA system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:911–20. doi: 10.1038/nrn2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kren BT, Wong PY, Sarver A, Zhang X, Zeng Y, Steer CJ. MicroRNAs identified in highly purified liver-derived mitochondria may play a role in apoptosis. RNA Biol. 2009;6:65–72. doi: 10.4161/rna.6.1.7534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krichevsky AM, King KS, Donahue CP, Khrapko K, Kosik KS. A microRNA array reveals extensive regulation of microRNAs during brain development. RNA. 2003;9:1274–81. doi: 10.1261/rna.5980303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krichevsky AM, Sonntag KC, Isacson O, Kosik KS. Specific microRNAs modulate embryonic stem cell-derived neurogenesis. Stem Cells. 2006;24:857–64. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kye MJ, Liu T, Levy SF, Xu NL, Groves BB, Bonneau R, Lao K, Kosik KS. Somatodendritic microRNAs identified by laser capture and multiplex RT-PCR. RNA. 2007;13:1224–34. doi: 10.1261/rna.480407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Yalcin A, Meyer J, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Identification of tissue-specific microRNAs from mouse. Curr Biol. 2002;12:735–9. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00809-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landgraf P, Rusu M, Sheridan R, Sewer A, Iovino N, Aravin A, Pfeffer S, Rice A, Kamphorst AO, Landthaler M, Lin C, Socci ND, Hermida L, Fulci V, Chiaretti S, Foa R, Schliwka J, Fuchs U, Novosel A, Muller RU, Schermer B, Bissels U, Inman J, Phan Q, Chien M, Weir DB, Choksi R, De Vita G, Frezzetti D, Trompeter HI, Hornung V, Teng G, Hartmann G, Palkovits M, Di Lauro R, Wernet P, Macino G, Rogler CE, Nagle JW, Ju J, Papavasiliou FN, Benzing T, Lichter P, Tam W, Brownstein MJ, Bosio A, Borkhardt A, Russo JJ, Sander C, Zavolan M, Tuschl T. A mammalian microRNA expression atlas based on small RNA library sequencing. Cell. 2007;129:1401–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Bates DJ, An J, Terry DA, Wang E. Up-regulation of key microRNAs, and inverse down-regulation of their predicted oxidative phosphorylation target genes, during aging in mouse brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:944–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugli G, Larson J, Martone ME, Jones Y, Smalheiser NR. Dicer and eIF2c are enriched at postsynaptic densities in adult mouse brain and are modified by neuronal activity in a calpain-dependent manner. J Neurochem. 2005;94:896–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugli G, Torvik VI, Larson J, Smalheiser NR. Expression of microRNAs and their precursors in synaptic fractions of adult mouse forebrain. J Neurochem. 2008;106:650–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05413.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin KC, Zukin RS. RNA trafficking and local protein synthesis in dendrites: an overview. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7131–4. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1801-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashov AK, Chintalgattu V, Islamov RR, Lever TE, Pak ES, Sierpinski PL, Katwa LC, Van Scott MR. RNAi pathway is functional in peripheral nerve axons. FASEB J. 2007;21:656–70. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6155com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natera-Naranjo O, Aschrafi A, Gioio AE, Kaplan BB. Identification and quantitative analyses of microRNAs located in the distal axons of sympathetic neurons. RNA. 2010;16:1516–29. doi: 10.1261/rna.1833310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen L, Klausen M, Helboe L, Nielsen FC, Werge T. MicroRNAs show mutually exclusive expression patterns in the brain of adult male rats. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CS, Tang SJ. Regulation of microRNA expression by induction of bidirectional synaptic plasticity. J Mol Neurosci. 2009;38:50–6. doi: 10.1007/s12031-008-9158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pena JT, Sohn-Lee C, Rouhanifard SH, Ludwig J, Hafner M, Mihailovic A, Lim C, Holoch D, Berninger P, Zavolan M, Tuschl T. miRNA in situ hybridization in formaldehyde and EDC-fixed tissues. Nat Methods. 2009;6:139–41. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasethupathy P, Fiumara F, Sheridan R, Betel D, Puthanveettil SV, Russo JJ, Sander C, Tuschl T, Kandel E. Characterization of small RNAs in Aplysia reveals a role for miR-124 in constraining synaptic plasticity through CREB. Neuron. 2009;63:803–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schratt G. microRNAs at the synapse. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:842–9. doi: 10.1038/nrn2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sempere LF, Freemantle S, Pitha-Rowe I, Moss E, Dmitrovsky E, Ambros V. Expression profiling of mammalian microRNAs uncovers a subset of brain-expressed microRNAs with possible roles in murine and human neuronal differentiation. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R13. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-3-r13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel G, Obernosterer G, Fiore R, Oehmen M, Bicker S, Christensen M, Khudayberdiev S, Leuschner PF, Busch CJ, Kane C, Hubel K, Dekker F, Hedberg C, Rengarajan B, Drepper C, Waldmann H, Kauppinen S, Greenberg ME, Draguhn A, Rehmsmeier M, Martinez J, Schratt GM. A functional screen implicates microRNA-138-dependent regulation of the depalmitoylation enzyme APT1 in dendritic spine morphogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:705–16. doi: 10.1038/ncb1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skup M. Dendrites as separate compartment - local protein synthesis. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 2008;68:305–21. doi: 10.55782/ane-2008-1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward O, Reeves TM. Protein-synthetic machinery beneath postsynaptic sites on CNS neurons: association between polyribosomes and other organelles at the synaptic site. J Neurosci. 1988;8:176–84. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-01-00176.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton MA, Schuman EM. Dendritic protein synthesis, synaptic plasticity, and memory. Cell. 2006;127:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Tian QB, Kuromitsu J, Kawai T, Endo S. Characterization of mRNA species that are associated with postsynaptic density fraction by gene chip microarray analysis. Neurosci Res. 2007;57:61–85. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent P, Mulle C. Kainate receptors in epilepsy and excitotoxicity. Neuroscience. 2009;158:309–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LL, Zhang Z, Li Q, Yang R, Pei X, Xu Y, Wang J, Zhou SF, Li Y. Ethanol exposure induces differential microRNA and target gene expression and teratogenic effects which can be suppressed by folic acid supplementation. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:562–79. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wibrand K, Panja D, Tiron A, Ofte ML, Skaftnesmo KO, Lee CS, Pena JT, Tuschl T, Bramham CR. Differential regulation of mature and precursor microRNA expression by NMDA and metabotropic glutamate receptor activation during LTP in the adult dentate gyrus in vivo. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31:636–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07112.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CW, Zeng F, Eberwine J. mRNA transport to and translation in neuronal dendrites. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2007;387:59–62. doi: 10.1007/s00216-006-0916-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.