Abstract

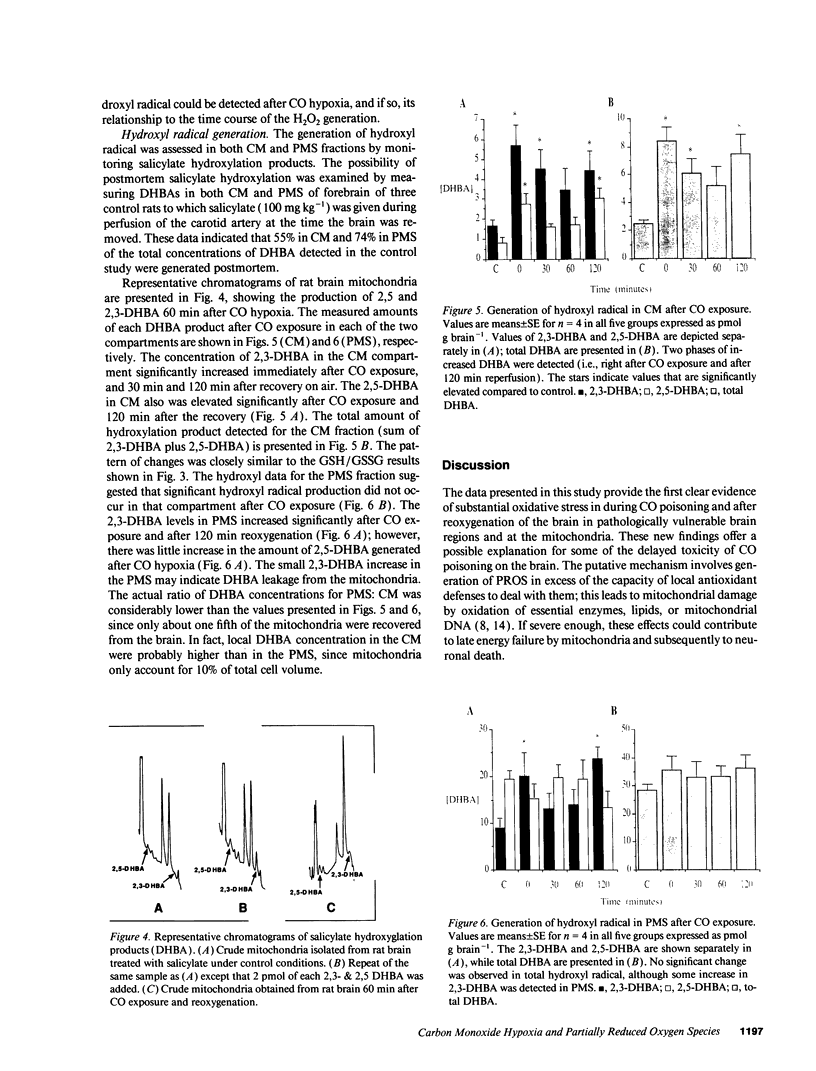

To better understand the mechanisms of tissue injury during and after carbon monoxide (CO) hypoxia, we studied the generation of partially reduced oxygen species (PROS) in the brains of rats subjected to 1% CO for 30 min, and then reoxygenated on air for 0-180 min. By determining H2O2-dependent inactivation of catalase in the presence of 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (ATZ), we found increased H2O2 production in the forebrain after reoxygenation. The localization of catalase to brain microperoxisomes indicated an intracellular site of H2O2 production; subsequent studies of forebrain mitochondria isolated during and after CO hypoxia implicated nearby mitochondria as the source of H2O2. In the mitochondria, two periods of PROS production were indicated by decreases in the ratio of reduced to oxidized glutathione (GSH/GSSG). These periods of oxidative stress occurred immediately after CO exposure and 120 min after reoxygenation, as indicated by 50 and 43% decreases in GSH/GSSG, respectively. The glutathione depletion data were supported by studies of hydroxyl radical generation using a salicylate probe. The salicylate hydroxylation products, 2,3 and 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHBA), were detected in mitochondria from CO exposed rats in significantly increased amounts during the same time intervals as decreases in GSH/GSSG. The DHBA products were increased 3.4-fold immediately after CO exposure, and threefold after 120 min reoxygenation. Because these indications of oxidative stress were not prominent in the postmitochondrial fraction, we propose that PROS generated in the brain after CO hypoxia originate primarily from mitochondria. These PROS may contribute to CO-mediated neuronal damage during reoxygenation after severe CO intoxication.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anderson M. E. Determination of glutathione and glutathione disulfide in biological samples. Methods Enzymol. 1985;113:548–555. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(85)13073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. D., Piantadosi C. A. In vivo binding of carbon monoxide to cytochrome c oxidase in rat brain. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1990 Feb;68(2):604–610. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.68.2.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. D., Piantadosi C. A. Recovery of energy metabolism in rat brain after carbon monoxide hypoxia. J Clin Invest. 1992 Feb;89(2):666–672. doi: 10.1172/JCI115633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark J. B., Nicklas W. J. The metabolism of rat brain mitochondria. Preparation and characterization. J Biol Chem. 1970 Sep 25;245(18):4724–4731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies K. J., Delsignore M. E., Lin S. W. Protein damage and degradation by oxygen radicals. II. Modification of amino acids. J Biol Chem. 1987 Jul 15;262(20):9902–9907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Río L. A., Ortega M. G., López A. L., Gorgé J. L. A more sensitive modification of the catalase assay with the Clark oxygen electrode. Application to the kinetic study of the pea leaf enzyme. Anal Biochem. 1977 Jun;80(2):409–415. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(77)90662-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd R. A., Henderson R., Watson J. J., Wong P. K. Use of salicylate with high pressure liquid chromatography and electrochemical detection (LCED) as a sensitive measure of hydroxyl free radicals in adriamycin treated rats. J Free Radic Biol Med. 1986;2(1):13–18. doi: 10.1016/0748-5514(86)90118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd R. A. Role of oxygen free radicals in carcinogenesis and brain ischemia. FASEB J. 1990 Jun;4(9):2587–2597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutases. An adaptation to a paramagnetic gas. J Biol Chem. 1989 May 15;264(14):7761–7764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grootveld M., Halliwell B. Aromatic hydroxylation as a potential measure of hydroxyl-radical formation in vivo. Identification of hydroxylated derivatives of salicylate in human body fluids. Biochem J. 1986 Jul 15;237(2):499–504. doi: 10.1042/bj2370499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALPERIN M. H., McFARLAND R. A., NIVEN J. I., ROUGHTON F. J. The time course of the effects of carbon monoxide on visual thresholds. J Physiol. 1959 Jun 11;146(3):583–593. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1959.sp006213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B., Gutteridge J. M. Role of free radicals and catalytic metal ions in human disease: an overview. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:1–85. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86093-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyslop P. A., Hinshaw D. B., Halsey W. A., Jr, Schraufstätter I. U., Sauerheber R. D., Spragg R. G., Jackson J. H., Cochrane C. G. Mechanisms of oxidant-mediated cell injury. The glycolytic and mitochondrial pathways of ADP phosphorylation are major intracellular targets inactivated by hydrogen peroxide. J Biol Chem. 1988 Feb 5;263(4):1665–1675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H., Mitchell J. R. Use of isolated perfused organs in hypoxia and ischemia/reperfusion oxidant stress. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:752–759. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86175-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labarca C., Paigen K. A simple, rapid, and sensitive DNA assay procedure. Anal Biochem. 1980 Mar 1;102(2):344–352. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olafsdottir K., Reed D. J. Retention of oxidized glutathione by isolated rat liver mitochondria during hydroperoxide treatment. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988 Mar 17;964(3):377–382. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(88)90038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piantadosi C. A., Tatro L. G. Regional H2O2 concentration in rat brain after hyperoxic convulsions. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1990 Nov;69(5):1761–1766. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.69.5.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell S. R., Hall D. Use of salicylate as a probe for .OH formation in isolated ischemic rat hearts. Free Radic Biol Med. 1990;9(2):133–141. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(90)90116-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai Y., Tanaka A., Ikai I., Yamaoka Y., Ozawa K., Orii Y. Measurement of cytochrome c oxidase activity in human liver specimens obtained by needle biopsy. Clin Chim Acta. 1988 Sep 15;176(3):343–346. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(88)90192-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasame H. A., Ames M. M., Nelson S. D. Cytochrome P-450 and NADPH cytochrome c reductase in rat brain: formation of catechols and reactive catechol metabolites. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1977 Oct 10;78(3):919–926. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(77)90510-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savolainen H., Kurppa K., Tenhunen R., Kivistö H. Biochemical effects of carbon monoxide poisoning in rat brain with special reference to blood carboxyhemoglobin and cerebral cytochrome oxidase activity. Neurosci Lett. 1980 Oct 2;19(3):319–323. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(80)90281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thom S. R. Carbon monoxide-mediated brain lipid peroxidation in the rat. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1990 Mar;68(3):997–1003. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.68.3.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. A., Hess M. L. The oxygen free radical system: a fundamental mechanism in the production of myocardial necrosis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1986 May-Jun;28(6):449–462. doi: 10.1016/0033-0620(86)90027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrens J. F., Freeman B. A., Levitt J. G., Crapo J. D. The effect of hyperoxia on superoxide production by lung submitochondrial particles. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1982 Sep;217(2):401–410. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(82)90518-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama Y., Beckman J. S., Beckman T. K., Wheat J. K., Cash T. G., Freeman B. A., Parks D. A. Circulating xanthine oxidase: potential mediator of ischemic injury. Am J Physiol. 1990 Apr;258(4 Pt 1):G564–G570. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1990.258.4.G564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusa T., Beckman J. S., Crapo J. D., Freeman B. A. Hyperoxia increases H2O2 production by brain in vivo. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1987 Jul;63(1):353–358. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.63.1.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Piantadosi C. A. Prevention of H2O2 generation by monoamine oxidase protects against CNS O2 toxicity. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1991 Sep;71(3):1057–1061. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.3.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]