The meaning of the term “inflammation” has undergone considerable evolution. Originally defined by Celsus’ four cardinal signs of “tumor, rubor, calor et dolor” (1), inflammation typically displays extravasation of blood cells—granulocytes in the beginning, and lymphocytes soon thereafter. The word “neuroinflammation,” however, is increasingly used to identify a radically different set of conditions that are specific to the central nervous system (CNS). Whereas viral, bacterial, and autoimmune diseases of the CNS can resemble their extraneural counterparts morphologically, the concept of “neuroinflammation” has gradually expanded to also describe diseases that display none of Celsus’ cardinal signs, do not attract conventional inflammatory cells, and that most neuropathologists would classify as degenerative rather than inflammatory. These “inflammatory” changes are restricted to a cell type exclusive to the CNS: the microglia.

Neuroinflammation is frequently viewed as deleterious to neurological function. Proliferation and activation of microglia occurs in most neurological diseases, from epilepsy to prion diseases. Consequently, the immune system is a major therapeutic target, even in CNS diseases whose primary pathogenesis is not obviously immunological. Indeed, the use of intravenously administered immunoglobulin to slow progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is entering Phase III clinical trials, and some patients with a fatal genetic demyelinating disease, X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy, now receive curative bone marrow transplants (BMTs) (2). Unfortunately, although there have been some victories, several high-profile immunotherapy trials for neurological diseases have recently failed (3). Few treatment options exist for patients, making the study of neuroimmune-mediated pathogenesis imperative.

In CNS inflammation, the blood-brain barrier (BBB) limits entry of patrolling bone marrow (BM)–derived immune cells. Instead, resident microglia perform normal surveillance. Microglia become rapidly activated in response to injury, undergoing morphological and molecular changes often associated with neurotoxicity. These changes are evident in postmortem human brain specimens, animal models of disease, and more recently, with the use of positron emission tomography with radiolabeled benzodiazepine receptor ligands in human patients (4). Their proximity to pathology and an arsenal of potentially cytotoxic molecules make microglia a prime suspect in neurological disease. However, growing evidence about the origin and function of microglia underscores the complexity of this association and the importance of distinguishing microglia from BM-derived macrophages. Here, we highlight our current understanding of microglia in disease with an emphasis, where possible, on recent in vivo experimental data.

What Are Microglia?

Microglia are parenchymal tissue macrophages with delicate branching processes (“ramified,” or treelike) that include 10% of cells in the CNS.

Unlike CNS macrophages found in the meninges, choroid plexus, and perivascular space, microglia derive from macrophages produced by primitive hematopoiesis in the yolk sac (5). These primitive macrophages migrate to the developing neural tube, where they give rise to microglia (6). BM-derived monocytes do not contribute to the mature microglial pool in the absence of conditioning irradiation to the CNS, suggesting that microglia are sustained by local progenitors (Fig. 1) (7, 8).

Fig. 1.

Microglia derive from yolk-sac macrophages formed during primitive hematopoiesis beginning at embryonic day 7.5 (E7.5) (the embryo is depicted at E11.5 for illustrative purposes). Primitive macrophages migrate to the developing nervous system where they become microglia and reside throughout life. Local progenitors sustain the microglial population. In contrast, other CNS macrophages—found in the perivascular (Virchow-Robin) space, meninges, and choroid plexus—derive from precursor blood monocytes. Monocytes are formed in the BM from hematopoietic stem cells. Hematopoiesis in the BM is dependent on a transcription factor, Myb. However, this protein is dispensable for the formation of primitive macrophages.

Yolk sac–derived macrophages develop independently of Myb, a requisite transcription factor for stem cell development in the BM (9). Microglia and BM-derived macrophages thus represent two genetically distinct myeloid populations.

These differences imply different functions for microglia and infiltrating macrophages, which are increasingly apparent in mouse models of disease (10, 11). Better methods are needed to specifically identify and manipulate each of these cell types Highly motile processes of “resting” microglia constantly survey the local microenvironment and rapidly respond to nearby injury with directed process or cell body migration (12, 13). Microglia clear apoptotic cells and are involved in both elimination and maintenance of synapses for proper neural circuit wiring. Some of these functions continue into adulthood. As our tools and technology for studying microglia grow, so too will our understanding of their role in the healthy brain (14).

Gene expression and morphological changes associated with microglial activation have been extensively studied (15). For example, neurons inhibit microglial activation through both receptorligand interactions that are dependent on contact (i.e., CD200 and its receptor) and secreted molecules such as fractalkine (CX3CL1) acting on the microglial receptor CX3CR1 [reviewed in (16)]. Derepression of these inhibitory influences likely promotes microglial activation. Recently, two pro-apoptotic caspases, capase-8 and caspase-3/7, were shown to promote microglial activation downstream of the pattern recognition receptor Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) in vitro (17). In a chemical-lesion model of Parkinson’s disease (PD), pharmacological inhibition of caspase-3/7 suppressed the induction of proinflammatory mediators, such as inducible nitric oxide synthase and tumor necrosis factor–a, and provided modest protection against dopaminergic neuron loss. In postmortem brain specimens from AD and PD patients, caspase expression increases in activated microglia. Furthermore, signaling through estrogen receptor b (ERb) suppresses inflammatory responses of both microglia and astrocytes in vitro (18). Administration of ERb ligands prevented progression of experimental autoimmune encephalitis (EAE), a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. The induction of EAE has been attributed to microglia (19) as well as monocyte infiltration (11), making it difficult to ascribe this effect specifically to microglial responses. Pumping Up Microglial Function to Treat AD Accumulation of b-amyloid (Ab) is a hallmark of AD, which contributes to the pathogenesis of both familial and sporadic AD (20). The net deposition of Ab equals production minus clearance, meaning that the mechanisms of clearance are as important as those of Ab generation. In vitro experiments strongly suggest a role for microglia in Ab phagocytosis but are wrought with technical constraints common to existing microglia culture systems. First, the nonphysiological addition of serum to growth media provides opsonins and activating substances microglia do not normally see in the CNS. Secondly, many of these studies are hampered by the inability to isolate microglia from other macrophages.

Two recent studies suggest that microglia do not influence Ab deposition or facilitate its clearance in multiple AD mouse models (10, 21). Selective depletion of microglia with the use of a lineage-ablation approach revealed no change in plaque formation, total Ab load, or neurotoxicity in an AD mouse model (21). This finding establishes that although microglia accumulate around Ab plaques, these cells do not contribute to their maintenance or clearance, at least on a short-term basis. To clarify a role for macrophages, BM chimeras were generated using lead to protect the brain and prevent peripheral monocyte infiltration (10). Selective loss of chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) in perivascular macrophages decreased the ability of these cells to phagocytose Ab and promoted an accumulation of Ab deposits surrounding the vasculature in another mouse model of AD. Restricted loss of CCR2 to this peripheral compartment resulted in cerebral amyloid angiopathy (22), supporting a role for perivascular macrophages in Ab clearance from the CNS. But maybe these mouse models do not fully mirror the situation in humans, as polymorphisms in the microglial receptor TREM2 have emerged among the most potent risk modifiers for AD (23, 24).

Although microglia may be dispensable for Ab clearance and disease progression in mice, can they be coaxed into helping to clear Ab? The strongest evidence for this concept comes from the observation that Ab plaques can be potently cleared by antibodies against pyroglutamyl-Ab, an Ab isoform that seems to exist only within plaques (25). Hence, Ab can be cleared not only by creating an immunological sink in the periphery, but also by antibodies that selectively opsonize plaques.

Furthermore, polymorphisms of apolipoprotein E (apoE), a lipoprotein modulating phagocytic functions, are the most substantial genetic risk factor for sporadic AD. Expression of apoE expression is controlled by transcription factors—nuclear hormone receptors peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARg) and liver X receptors (LXRs)—whose long-term activation reverses neuropathological changes in Ab-overexpressing mice (26). LXR and PPARg exert their function by forming heterodimers with retinoid X receptors (RXRs); treatment of Ab mice with the RXR agonist bexarotene decreases Ab levels and plaque burden and even restores cognitive functions (27), but only if mice express apoE. Though efficacy trials are needed to test off-label use of bexarotene (28), RXR agonism represents a promising therapeutic target for AD treatment.

Alternative Views of Repair

A key mechanism by which nuclear receptor activation promotes Ab clearance may be the polarization, or differential activation patterns, of microglia. Macrophages, and probably microglia, are tuned for different types of host defense and protection, depending on the presence of available cytokines. Classical, or “M1,” polarizing signals arm macrophages to elicit proinflammatory and cytotoxic mediators, whereas alternatively activated “M2” macrophages can dampen inflammation and promote tissue regeneration (29). Although these two phenotypes probably fall on a continuum, PPARs act as master regulators of the M2 phenotype in macrophages. Pioglitazone, a PPARg agonist that confers protection in Aboverexpressing mice, strongly induces expression of M2-associated genes in microglia and macrophages (30).

Microglia and macrophage subsets may be beneficial in traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI). After SCI, peripheral monocytes infiltrate the injury site and differentiate into macrophages. These infiltrating cells are necessary for the limited functional recovery observed after SCI (31). Furthermore, both M1 and M2 macrophages are found at the injury site, with M2s constituting only a minority of cells. Interestingly, when isolated M2 macrophages are injected intraspinally after SCI, the expression level of M2-associated genes declines, suggesting that the injured CNS microenvironment suppresses the M2 phenotype (32).

Several findings suggest that proinflammatory macrophages are detrimental to CNS repair. Ablation of CX3CR1, which is expressed by microglia and some macrophages, promotes functional recovery after SCI and results in smaller lesions (33). Peripheral loss of CX3CR1, which normally follows injury, prevents the infiltration of Ly6Clo/iNOS+ (iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase) macrophages. It is unknown if the latter subset is M1-like, though CX3CR1−/− mice exhibit decreased expression of proinflammatory cytokines in CNS macrophages and microglia after SCI. It is also possible that microglial loss of CX3CR1 contributes to CNS repair, perhaps by influencing the profile of infiltrating cells. Although functional recovery was limited, these data suggest that proinflammatory M1 macrophages are detrimental to repair.

Under certain circumstances, boosting inflammation can also promote CNS regeneration. Lens injury, or intraocular injection of TLR2 agonists, promotes axon regeneration after optic nerve injury, and combinatorial therapy with neuron-specific Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog (PTEN) deletion and increased cyclic adenosine monophosphate facilitates long-distance axon regeneration and partial behavioral recovery (34). Finally, zymosan-activated macrophages stimulate axon regeneration—although when administered alone, they also trigger some neurotoxicity (35), highlighting the delicate balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory signals after CNS injury.

Although the above studies do not directly address the importance of microglial polarization in CNS repair, a study aimed at understanding the phenomenon of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)–induced neuroprotection may hold some clues (36). LPS is a TLR4 ligand that, when administered intraperitoneally, causes strong, proinflammatory microglial activation. Intrastriatal LPS injection is profoundly neurotoxic, yet repeated low-dose exposure to LPS affords neuroprotection against subsequent CNS injuries, an effect prevented by TLR4 ablation. The mechanism of preconditioning is intriguing because low-dose LPS treatment does not cause BBB breakdown or monocyte infiltration. Ablation of TLR4 from circulating immune cells did not suppress LPS-induced microglial activation and partial protection from cryogenic brain injury, whereas administration of wild-type (WT) BM to TLR4−/− mice abolished those effects (36). Thus, expression of TLR4 by microglia, but not macrophages, is required for LPS-induced preconditioning. Finally, gene-expression analyses of the whole brain after preconditioning reveal an increase in M2-associated transcripts, suggesting that LPS-conditioned microglia may be activated through an alternative pathway. Although the causality of M2 microglia in repair and protection needs further validation, these findings indicate that microglia are capable soldiers for CNS repair.

Microglia: Your Ally Against Prions

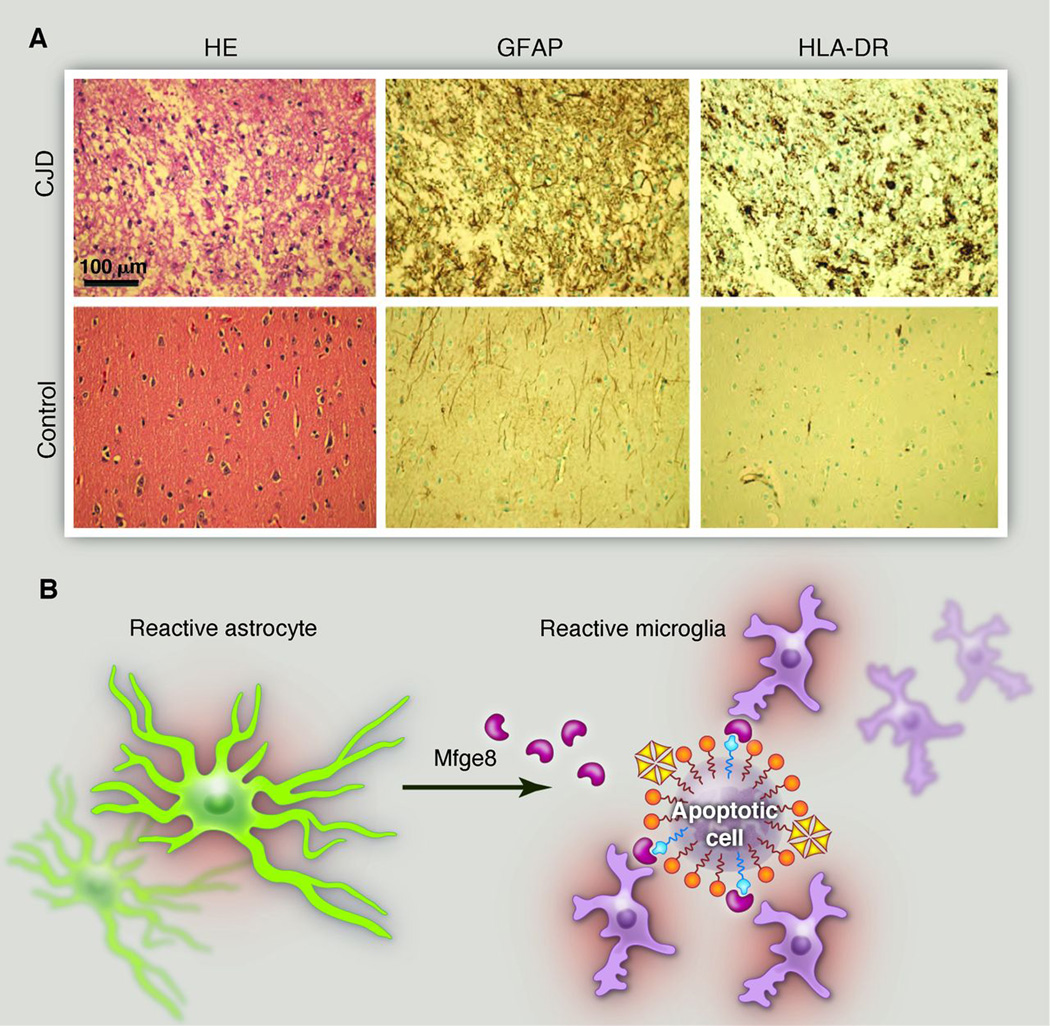

Although most brain diseases exhibit some degree of neuroinflammation, the most dramatic instance of microglial and astrocytic activation is undoubtedly seen in prion disease. Progressive protein misfolding and aggregation of disease-associated prion protein (PrPSc) leads to fatal spongiform encephalopathies. At the terminal stage, the cortex of a patient with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease often resembles a monoculture of excessively activated astrocytes and micro glia, with very few remaining neurons (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Microglia and prions. (A) The cerebral cortex of a patient who died of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD). The pyramidal cells are almost entirely obliterated and replaced by a monoculture of microglia and, to a lesser extent, astrocytes. Note the pseudolaminar pattern of vacuolation (“status spongiosus”), which indicates a ribbon of pathological prion deposition. HE, hematoxylin and eosin staining; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein (an astrocyte marker); HLA-DR, human leukocyte antigen class II. (B) By virtue of its dual binding domains for both phosphatidyl serine and integrins, the secreted factor Mfge8 can bridge apoptotic cells and phagocytes (56). The excessive accumulation of PrPSc in Mfge8-deficient mice infected with prions suggests that microglia use the Mfge8 pathway to clear aggregated and misfolded proteins (38). Mfge8 is produced by astrocytes in the brain and by follicular dendritic cells in lymphoid organs, demonstrating that stromal cells secrete a local “licensing factor” that arms hematopoietic cells and enables the disposal of toxic detritus (57, 58).

Microglia and macrophages can phagocytose PrPSc aggregates in vitro, but in vivo removal of PrPSc is relatively inefficient (37), and in the final stage of disease, prions ultimately win against microglia. Moreover, whereas phagocytosis is probably beneficial, failure to degrade prions may transform microglia into well-meaning yet lethal saboteurs that spread the disease by virtue of their motility.

To sort out the function of microglia in prion disease, cerebellar organotypic cultured slices from CD11b-HSVTK mice were treated with ganciclovir to induce microglial depletion (38). Surprisingly, loss of microglia resulted in vastly enhanced PrPSc deposits and augmented prioninfectivity titers. This effect was recapitulated in vivo with loss of milk fat globule–epidermal growth factor 8 protein (Mfge8), an astrocytesecreted protein that binds phosphatidyl serine on the surface of apoptotic cells and promotes phagocytic clearance. Mfge8-deficient mice exhibited accelerated prion pathogenesis and increased numbers of apoptotic cell corpses, suggesting that Mfge8-mediated apoptotic cell clearance quells prion accumulation (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, the effect of Mfge8 depletion was visible in only certain mouse strains, implying the existence of further polymorphic determinants of prion removal, potentially including the Del-1 immunoregulator (39). Although astrocytes may also contribute to phagocytosis of these cells, these experiments reveal a protective function for microglia in prion disease and potential insights about the cross talk between microglia and astrocytes in neuroinflammation.

Development Complements Neurodegeneration

Developmental elimination of inappropriate synapses is critical for the proper wiring of the CNS. This process is mediated by proteins in the classical complement cascade, a robust immune signaling pathway that tags debris or pathogens for phagocytosis by immune cells (40). During development, complement proteins C1q andC3 become localized to synapses.

Recently, microglia were identified as the phagocytes responsible for elimination of tagged synapses via complement receptor 3(CR3) signaling (Fig. 3A and B)(41). Immuno–electron microscopy revealed the active phagocytosis of presynaptic elements by microglia in the healthy, developing lateral geniculate nucleus(LGN). Mice without CR3or C3 cannot effectively prune synapses, as evidenced by a sustained deficit in segregation of eye-specific axonal projections to the LGN. Microglia likely sculpt neural circuits throughout the CNS, because they also contribute in the developing hippocampus(42).

Fig. 3.

Microglia prune synapses during development in a complement-dependent manner. Segregation of eye-specific inputs in the LGN requires the expression of CR3 (A) and C3. KO, knockout. Scale bar, 100 µm. (B) Microglia in the developing LGN contain phagocytosed synaptic elements and cholera toxin B subunit–labeled axons from both the contralateral and ipsilateral eyes, except in mice with deficient C3 signaling. [(A) and (B) are reproduced with permission from Neuron (41)] (C) This developmental process, in which an unknown factor released by astrocytes induces expression of C1q by neurons and microglia to promote C3-dependent synapse elimination, may be reactivated in neurodegenerative disease. [Adapted from (43)]

If complement proteins tag synapses for elimination by microglia during development, could this underlie the synaptic loss observed in this and other neurodegenerative diseases (Fig. 3C)? Examination of human brain tissue reveals strong induction of the complement cascade in many neurodegenerative diseases (43).

In a mouse model of glaucoma, one of the most common neurodegenerative diseases, complement pathway expression is up-regulated long before retinal ganglion cell death (40). Immunohistochemistry revealed that robust C1q immunoreactivity in the microglia of mutant mice precede pathological changes, suggesting that induction is an early event in pathogenesis (44). Importantly loss of C1q strongly protected mutant mice from glaucoma.

Interestingly, microglial activation and synapse loss precede pathologic changes in mice carrying the Pro301→Leu301 human tau mutation (45) and beg the question of whether complement cascade inhibition could limit tauopathy in this model. Mice expressing a soluble variant of the natural complement inhibitor, complement receptor-related gene/protein y (sCrry) had decreased tau aggregation. In addition, inducing abnormal tau expression in mice lacking Cd59a, a potent inhibitor of the terminal stages of the complement cascade, resulted increased tau aggregation and neuron loss compared with mice expressing the inhibitor (46).

Thus, complement cascade suppression is neuroprotective. The relation between complement induction and synapse loss in neuropathology is not yet clear. Neurodevelopment suggests that neural activity and signaling from astrocytes may induce complement expression (40). Are synapses in neurodegenerative disease inappropriately tagged, or are they inefficiently remodeled by aging or sick microglia? Understanding these mechanisms will likely reveal novel therapeutic strategies and clarify the function of microglia in neurodegenerative disease.

Microglia and Psychiatric Disease

Because microglia sculpt neural circuits, can dysfunction contribute to neurodevelopmental or psychiatric disorders? In an unexpected paradigm shift, immune cells may play a crucial role in diseases that are traditionally considered to be neuronal, including autism-spectrum and obsessive-compulsive disorders.

Pathological grooming in mice, reminiscent of the human impulsive-control disorder trichotillomania, is due to loss of Hoxb8 in the hematopoietic compartment (47). Mice with complete loss or specific deletion of Hoxb8 in Tie2-expressing cells (myeloid and endothelial cells) spent twice as long grooming as their littermates, leading to hair loss and skin lesions. Lethal irradiation of Hoxb8−/− mice followed by BM reconstitution with WT cells rescues this phenotype. Donor BM from animals without B or T cells successfully restored normal grooming in Hoxb8−/− mice, suggesting that expression of Hoxb8 by myeloid cells is compulsory for normal grooming. Because this strategy was employed for transplantation, donor cells engrafted into recipient brains, making it difficult to discern if Hoxb8 is required in microglia, macrophages, or both.

Microglia may also have an impact on Rett’s syndrome, an X-linked autism spectrum disorder caused by the loss of function of methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2). MeCP2 selectively binds methylated DNA (48) and controls the expression of epigenetically “imprinted” genes. Girls affected by Rett’s syndrome can develop normally during the first 6 to 18 months of life before developmental regression and the onset of seizures, irregular breathing, and progressive neurological signs. The connection between MeCP2 loss-of-function mutations and Rett’s syndrome suggests that control of imprinting is crucial to neuronal function.

In male mice, MeCP2–/y causes growth retardation, tremor, apnea, and gait and locomotor abnormalities. Loss of MeCP2 in neurons recapitulates the full knockout phenotype. Intriguingly, selective return of MeCP2 function to either microglia or astrocytes arrests Rett’s syndrome pathology (49, 50). Quite surprisingly, restoration of MeCP2 expression in astrocytes of juvenile MeCP2-deficient mice prolonged life span, repaired respiratory function, and reversed neuronal abnormalities (50). Given the non–cell-autonomous effects of MeCP2, WT BM transplanted into MeCP2-deficient mice led to a dramatic improvement in life span, breathing patterns, and locomotor activity, compared with mice transplanted with MeCP2-deficient BM (49). Preventing the engraftment of donor cells into the CNS by head shielding during irradiation eliminated the benefits of MeCP2 reconstitution, suggesting that MeCP2+ microglia are required for the effect. The mechanism is unclear but may relate to phagocytic ability, because infusion of annexin V to prevent recognition of debris by phagocytes prevents the therapeutic effects of MeCP2 reconstitution. Thus, MeCP2’s CNS function may be related to transcription of secreted factors necessary for normal neuronal development or redundancy of MeCP2-mediated functions by microglia, astrocytes, and neurons.

The findings with Hoxb8 and MeCP2 highlight an emerging principle in treating neurological diseases: If microglial dysfunction underlies a specific pathology, BMT may be an effective therapy. This theory has been successfully pioneered in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (2) and is being tested as a last-resort treatment for aggressive multiple sclerosis (51). Importantly, both of these conditions are associated with autoimmune infiltration of lymphocytes. Transplantation-based treatments for other neurological diseases, though exciting, warrant caution given the high risks of BMT. In addition, the emerging discord between microglial and BM-derived macrophage function necessitates future studies to determine whether engrafted BM-derived donor cells function like microglia.

Scapegoat or Saboteur?

One may be forgiven for concluding that our understanding of microglial biology is lacking, despite decades of research in this area (52). Yet, compelling experimental and clinical evidence exists in support of the notion that microglia act as both as “bad cop” and “good cop” in distinct circumstances.

Trying to identify the best microglial response to injury is difficult. The relationship of M1- and M2-polarized microglia is complex, because M1s might promote axon regeneration but be neurotoxic, and M2s may lack the necessary environmental signals to maintain their phenotype. At least in AD mouse models, increasing the M2 phenotype is promising, but the jury is still out for other diseases. Furthermore, overactivation or activation status may not be the only way in which microglia contribute to disease. Disruption of normal homeostatic functions of microglia lead to neural circuitry abnormalities, which could contribute to conditions lacking overt inflammation, such as neuropsychiatric disease (53). It seems likely that our understanding of microglial function in health and disease will continue to divest from that of other CNS and infiltrating macrophages. Such investigations require the development of new tools to manipulate microglia. Finally, whereas microglia are the resident myeloid cells of the CNS, astrocytes become reactive after injury, promote glial scar formation, are important components of neuroinflammation (54), and may function as phagocytes (55). The interplay between microglia and astrocytes is exciting and largely unexplored territory for inquiry. The findings in relation toMfge8-mediated microglial phagocytosis of prion protein (38) and the as-yet unidentified astrocyte signal that induced complement deposition at synapses are just the beginning (40). The function of astrocytes in disease and their cross talk with microglia may hold important clues about neurological pathogenesis.

Summary

Although the CNS was historically considered to be immune-privileged, the emerging presence of microglia in health and disease demonstrates that the CNS and the immune system are tightly coupled. Although CNS inflammation may have some differences from other tissues, it is every bit as nuanced. Studies investigating the contribution of microglia to disease processes identify beneficial, detrimental, and dispensable functions for these cells. However, new tools to specifically study microglial function as distinct from that of macrophages are now crucial to provide new insight into neuroinflammation and pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

A.A. is the recipient of an Advanced Grant of the European Research Council and is supported by grants from the European Union (PRIORITY, LUPAS), the Swiss National Foundation, the Foundation Alliance BioSecure, the Clinical Research Focus Program of the University of Zurich, and the Novartis Research Foundation. B.A.B. is a cofounder of Annexon, Inc., a company that is making drugs for neurological diseases.

References

- 1.Celsus AC. De Medicina. Firenze, Italy: Nicolaus Laurentii; 1478. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cartier N, et al. Science. 2009;326:818. doi: 10.1126/science.1171242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Callaway EE. Nature. 2012;489:13. doi: 10.1038/489013a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schweitzer PJ, Fallon BA, Mann JJ, Kumar JSD. Drug Discov. Today. 2010;15:933. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alliot F, Godin I, Pessac B. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 1999;117:145. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ginhoux F, et al. Science. 2010;330:841. doi: 10.1126/science.1194637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ajami B, Bennett JL, Krieger C, Tetzlaff W, Rossi FMV. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:1538. doi: 10.1038/nn2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hickey WF, Vass K, Lassmann H. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1992;51:246. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulz C, et al. Science. 2012;336:86. doi: 10.1126/science.1219179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mildner A, et al. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:11159. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6209-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ajami B, Bennett JL, Krieger C, McNagny KM, Rossi FMV. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14:1142. doi: 10.1038/nn.2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nimmerjahn A, Kirchhoff F, Helmchen F. Science. 2005;308:1314. doi: 10.1126/science.1110647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wake H, Moorhouse AJ, Jinno S, Kohsaka S, Nabekura J. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:3974. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4363-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tremblay ME, et al. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:16064. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4158-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lucin KM, Wyss-Coray T. Neuron. 2009;64:110. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ransohoff RM, Cardona AE. Nature. 2010;468:253. doi: 10.1038/nature09615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burguillos MA, et al. Nature. 2011;472:319. doi: 10.1038/nature09788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saijo K, Collier JG, Li AC, Katzenellenbogen JA, Glass CK. Cell. 2011;145:584. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heppner FL, et al. Nat. Med. 2005;11:146. doi: 10.1038/nm1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jonsson T, et al. Nature. 2012;488:96. doi: 10.1038/nature11283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grathwohl SA, et al. Nat. Neurosci. 2009;12:1361. doi: 10.1038/nn.2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El Khoury J, et al. Nat. Med. 2007;13:432. doi: 10.1038/nm1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guerreiro R, et al. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012 10.1056/ NEJMoa1211851. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jonsson T, et al. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012 10.1056/NEJMoa1211103. [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeMattos RB, et al. Neuron. 2012;76:908. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mandrekar-Colucci S, Landreth GE. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2011;15:1085. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.594043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cramer PE, et al. Science. 2012;335:1503. doi: 10.1126/science.1217697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lowenthal J, Hull SC, Pearson SD. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:488. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1203104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chawla A, Nguyen KD, Goh YPS. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011;11:738. doi: 10.1038/nri3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mandrekar-Colucci S, Karlo JC, Landreth GE. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:10117. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5268-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shechter R, et al. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000113. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kigerl KA, et al. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:13435. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3257-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donnelly DJ, et al. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:9910. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2114-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Lima S, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012;109:9149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119449109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gensel JC, et al. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:3956. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3992-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen Z, et al. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:11706. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0730-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hughes MM, Field RH, Perry VH, Murray CL, Cunningham C. Glia. 2010;58:2017. doi: 10.1002/glia.21070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kranich J, et al. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:2271. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi EY, et al. Science. 2008;322:1101. doi: 10.1126/science.1165218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stevens B, et al. Cell. 2007;131:1164. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schafer DP, et al. Neuron. 2012;74:691. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paolicelli RC, et al. Science. 2011;333:1456. doi: 10.1126/science.1202529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stephan AH, Barres BA, Stevens B. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2012;35:369. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Howell GR, et al. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:1429. doi: 10.1172/JCI44646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshiyama Y, et al. Neuron. 2007;53:337. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Britschgi M, et al. J. Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:220. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen S-K, et al. Cell. 2010;141:775. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meehan RR, Lewis JD, McKay S, Kleiner EL, Bird AP. Cell. 1989;58:499. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90430-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Derecki NC, et al. Nature. 2012;484:105. doi: 10.1038/nature10907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lioy DT, et al. Nature. 2011;475:497. doi: 10.1038/nature10214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fassas A, et al. Neurology. 2011;76:1066. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318211c537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.del Rio-Hortega P, Penfield W. Bull. Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1892;41:278. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Blank T, Prinz M. Glia. 2012 10.1002/glia.22372. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zamanian JL, et al. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:6391. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6221-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cahoy JD, et al. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:264. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4178-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hanayama R, et al. Nature. 2002;417:182. doi: 10.1038/417182a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kranich J, et al. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:1293. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krautler NJ, et al. Cell. 2012;150:194. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]