Abstract

In its largest outbreak, Ebola virus disease is spreading through Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Nigeria. We sequenced 99 Ebola virus genomes from 78 patients in Sierra Leone to ∼2000× coverage. We observed a rapid accumulation of interhost and intrahost genetic variation, allowing us to characterize patterns of viral transmission over the initial weeks of the epidemic. This West African variant likely diverged from central African lineages around 2004, crossed from Guinea to Sierra Leone in May 2014, and has exhibited sustained human-to-human transmission subsequently, with no evidence of additional zoonotic sources. Because many of the mutations alter protein sequences and other biologically meaningful targets, they should be monitored for impact on diagnostics, vaccines, and therapies critical to outbreak response.

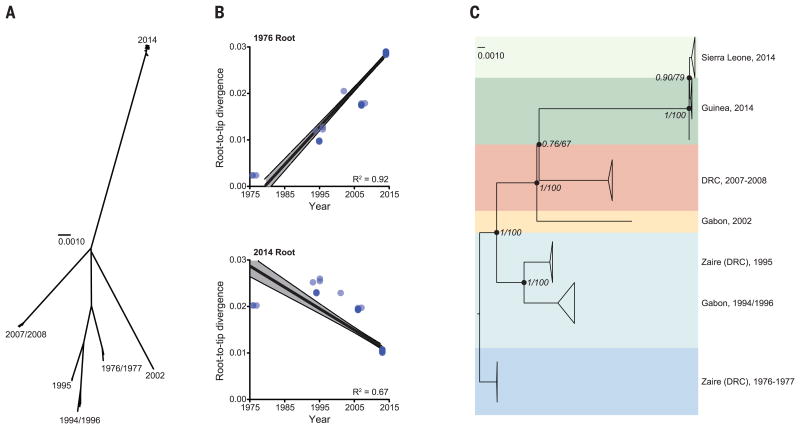

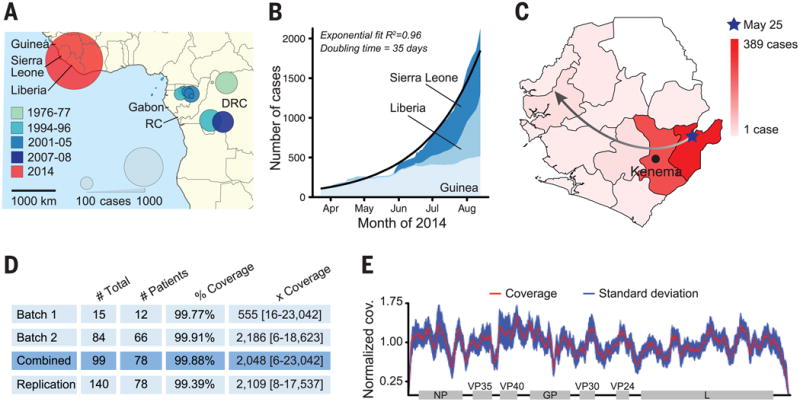

Ebola virus (EBOV; formerly Zaire ebolavirus), one of five ebolaviruses, is a lethal human pathogen, causing Ebola virus disease (EVD) with an average case fatality rate of 78% (1). Previous EVD outbreaks were confined to remote regions of central Africa; the largest, in 1976, had 318 cases (2) (Fig. 1A). The current outbreak started in February 2014 in Guinea, West Africa (3) and spread into Liberia in March, Sierra Leone in May, and Nigeria in late July. It is the largest known EVD outbreak and is expanding exponentially, with a doubling period of 34.8 days (Fig. 1B). As of 19 August 2014, 2240 cases and 1229 deaths have been documented (4, 5). Its emergence in the major cities of Conakry (Guinea), Freetown (Sierra Leone), Monrovia (Liberia), and Lagos (Nigeria) raises the specter of increasing local and international dissemination.

Fig. 1. Ebola outbreaks, historical and current.

(A) Historical EVD outbreaks, colored by decade. Circle area represents total number of cases (RC = Republic of the Congo; DRC = Democratic Republic of Congo). (B) 2014 outbreak growth (confirmed, probable, and suspected cases). (C) Spread of EVD in Sierra Leone by district. The gradient denotes number of cases; the arrow depicts likely direction. (D) EBOV samples from 78 patients were sequenced in two batches, totaling 99 viral genomes [replication = technical replicates (6)]. Mean coverage and median depth of coverage with range are shown. (E) Combined coverage (normalized to the sample average) across sequenced EBOV genomes.

In an ongoing public health crisis, where accurate and timely information is crucial, new genomic technologies can provide near-real-time insights into the pathogen's origin, transmission dynamics, and evolution. We used massively parallel viral sequencing to understand how and when EBOV entered human populations in the 2014 West African outbreak, whether the outbreak is continuing to be fed by new transmissions from its natural reservoir, and how the virus changed, both before and after its recent jump to humans.

In March 2014, Kenema Government Hospital (KGH) established EBOV surveillance in Kenema, Sierra Leone, near the origin of the 2014 outbreak (Fig. 1C and fig. S1) (6). Following standards for field-based tests in previous (7) and current (3) outbreaks, KGH performed conventional polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based EBOV diagnostics (8) (fig. S2); all tests were negative through early May. On 25 May, KGH scientists confirmed the first case of EVD in Sierra Leone. Investigation by the Ministry of Health and Sanitation (MoHS) uncovered an epidemiological link between this case and the burial of a traditional healer who had treated EVD patients from Guinea. Tracing led to 13 additional cases—all females who attended the burial. We obtained ethical approval from MoHS, the Sierra Leone Ethics and Scientific Review Committee, and our U.S. institutions to sequence patient samples in the United States according to approved safety standards (6).

We evaluated four independent library preparation methods and two sequencing platforms (9) (table S1) for our first batch of 15 inactivated EVD samples from 12 patients. Nextera library construction and Illumina sequencing provided the most complete genome assembly and reliable intrahost single-nucleotide variant (iSNV, frequency >0.5%) identification (6). We used this combination for a second batch of 84 samples from 66 additional patients, performing two independent replicates from each sample (Fig. 1D). We also sequenced 35 samples from suspected EVD cases that tested negative for EBOV; genomic analysis identified other known pathogens, including Lassa virus, HIV-1, enterovirus A, and malaria parasites (fig. S3).

In total, we generated 99 EBOV genome sequences from 78 confirmed EVD patients, representing more than 70% of the EVD patients diagnosed in Sierra Leone from late May to mid-June; we used multiple extraction methods or time points for 13 patients (table S2). Median coverage was >2000×, spanning more than 99.9% of EBOV coding regions (Fig. 1, D and E, and table S2).

We combined the 78 Sierra Leonean sequences with three published Guinean samples (3) [correcting 21 likely sequencing errors in the latter (6)] to obtain a data set of 81 sequences. They reveal 341 fixed substitutions (35 nonsynonymous, 173 synonymous, and 133 noncoding) between the 2014 EBOV and all previously published EBOV sequences, with an additional 55 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs; 15 nonsynonymous, 25 synonymous, and 15 noncoding), fixed within individual patients, within the West African outbreak. Notably, the Sierra Leonean genomes differ from PCR probes for four separate assays used for EBOV and pan-filovirus diagnostics (table S3).

Deep-sequence coverage allowed identification of 263 iSNVs (73 nonsynonymous, 108 synonymous, 70 noncoding, and 12 frameshift) in the Sierra Leone patients (6). For all patients with multiple time points, consensus sequences were identical and iSNV frequencies remained stable (fig. S4). One notable intrahost variation is the RNA editing site of the glycoprotein (GP) gene (fig. S5A) (10–12), which we characterized in patients (6).

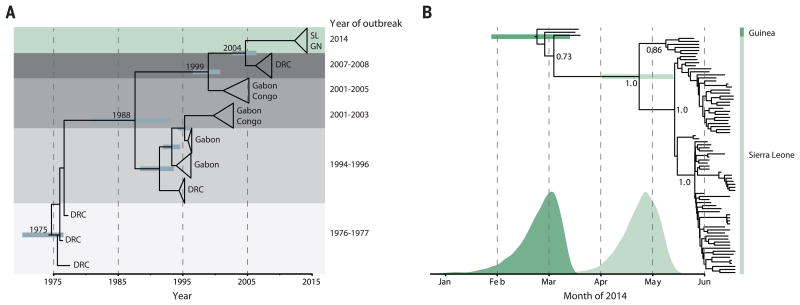

Phylogenetic comparison to all 20 genomes from earlier outbreaks suggests that the 2014 West African virus likely spread from central Africa within the past decade. Rooting the phytogeny using divergence from other ebolavirus genomes is problematic (Fig. 2A and fig. S6) (6, 13). However, rooting the tree on the oldest outbreak reveals a strong correlation between sample date and root-to-tip distance, with a substitution rate of 8 × 10−4 per site per year (Fig. 2B and fig. S7) (13). This suggests that the lineages of the three most recent outbreaks all diverged from a common ancestor at roughly the same time, around 2004 (Fig. 2C and Fig. 3A), which supports the hypothesis that each outbreak represents an independent zoonotic event from the same genetically diverse viral population in its natural reservoir.

Fig. 2. Relationship between outbreaks.

(A) Unrooted phylogenetic tree of EBOV samples; each major clade corresponds to a distinct outbreak (scale bar = nucleotide substitutions per site). (B) Root-to-tip distance correlates better with sample date when rooting on the 1976 branch (R2 = 0.92, top) than on the 2014 branch (R2 = 0.67, bottom). (C) Temporally rooted tree from (A).

Fig. 3. Molecular dating of the 2014 outbreak.

(A) BEAST dating of the separation of the 2014 lineage from central African lineages [SL, Sierra Leone; GN, Guinea; DRC, Democratic Republic of Congo; time of most recent common ancestor (tMRCA), September 2004; 95% highest posterior density (HPD), October 2002 to May 2006]. (B) BEAST dating of the tMRCA of the 2014 West African outbreak (23 February; 95% HPD, 27 January to 14 March) and the tMRCA of the Sierra Leone lineages (23 April; 95% HPD, 2 April to 13 May). Probability distributions for both 2014 divergence events are overlaid below. Posterior support for major nodes is shown.

Genetic similarity across the sequenced 2014 samples suggests a single transmission from the natural reservoir, followed by human-to-human transmission during the outbreak. Molecular dating places the common ancestor of all sequenced Guinea and Sierra Leone lineages around late February 2014 (Fig. 3B), 3 months after the earliest suspected cases in Guinea (3); this coalescence would be unlikely had there been multiple transmissions from the natural reservoir. Thus, in contrast to some previous EVD outbreaks (14), continued human-reservoir exposure is unlikely to have contributed to the growth of this epidemic in areas represented by available sequence data.

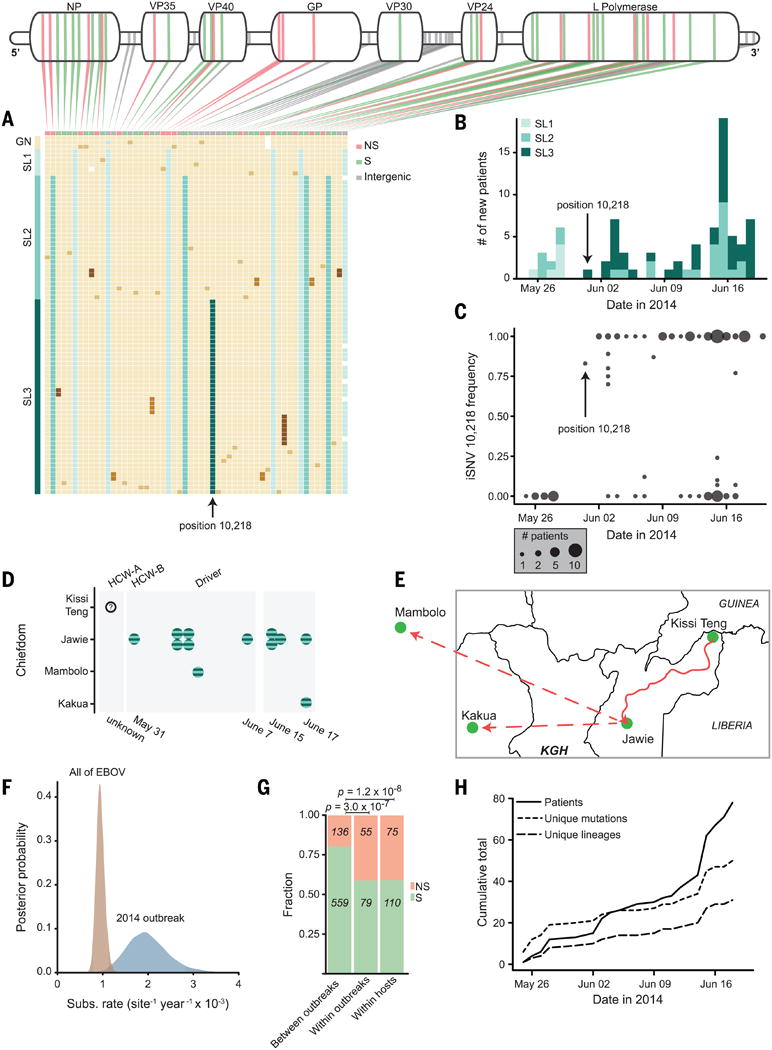

Our data suggest that the Sierra Leone outbreak stemmed from the introduction of two genetically distinct viruses from Guinea around the same time. Samples from 12 of the first EVD patients in Sierra Leone, all believed to have attended the funeral of an EVD case from Guinea, fall into two distinct clusters (clusters 1 and 2) (Fig. 4A and fig. S8). Molecular dating places the divergence of these two lineages in late April (Fig. 3B), predating their co-appearance in Sierra Leone in late May (Fig. 4B); this finding suggests that the funeral attendees were most likely infected by two lineages then circulating in Guinea, possibly at the funeral (fig. S9). All subsequent diversity in Sierra Leone accumulated on the background of those two lineages (Fig. 4A), consistent with epidemiological information from tracing contacts.

Fig. 4. Viral dynamics during the 2014 outbreak.

(A) Mutations, one patient sample per row; beige blocks indicate identity with the Kissidougou Guinean sequence (GenBank accession KJ660346).The top row shows the type of mutation (green, synonymous; pink, nonsynonymous; gray, inter-genic), with genomic locations indicated above. Cluster assignments are shown at the left. (B) Number of EVD-confirmed patients per day, colored by cluster. Arrow indicates the first appearance of the derived allele at position 10,218, distinguishing clusters 2 and 3. (C) Intrahost frequency of SNP 10,218 in all 78 patients (absent in 28 patients, polymorphic in 12, fixed in 38). (D and E) Twelve patients carrying iSNV 10,218 cluster geographically and temporally (HCW-A = unse-quenced health care worker; Driver drove HCW-A from Kissi Teng to Jawie, then continued alone to Mambolo; HCW-B treated HCW-A). KGH = location of Kenema Government Hospital. (F) Substitution rates within the 2014 outbreak and between all EVD outbreaks. (G) Proportion of nonsynonymous changes observed on different time scales (green, synonymous; pink, nonsynonymous). (H) Acquisition of genetic variation over time. Fifty mutational events (short dashes) and 29 new viral lineages (long dashes) were observed (intrahost variants not included).

Patterns in observed intrahost and interhost variation provide important insight about transmission and epidemiology. Groups of patients with identical viruses or with shared intrahost variation show temporal patterns suggesting transmission links (fig. S10). One iSNV (position 10,218) shared by 12 patients is later observed as fixed within 38 patients, becoming the majority allele in the population (Fig. 4C) and defining a third Sierra Leone cluster (Fig. 4, A and D, and fig. S8). Repeated propagation at intermediate frequency suggests that transmission of multiple viral haplotypes may be common. Geographic, temporal, and epidemiological metadata support the transmission clustering inferred from genetic data (Fig. 4, D and E, and fig. S11) (6).

The observed substitution rate is roughly twice as high within the 2014 outbreak as between outbreaks (Fig. 4F). Mutations are also more frequently nonsynonymous during the outbreak (Fig. 4G). Similar findings have been seen previously (15) and are consistent with expectations from incomplete purifying selection (16–18). Determining whether individual mutations are deleterious, or even adaptive, would require functional analysis; however, the rate of non-synonymous mutations suggests that continued progression of this epidemic could afford an opportunity for viral adaptation (Fig. 4H), underscoring the need for rapid containment.

As in every EVD outbreak, the 2014 EBOV variant carries a number of genetic changes distinct to this lineage; our data do not address whether these differences are related to the severity of the outbreak. However, the catalog of 395 mutations, including 50 fixed nonsynonymous changes with 8 at positions with high levels of conservation across ebolaviruses, provides a starting point for such studies (table S4).

To aid in relief efforts and facilitate rapid global research, we have immediately released all sequence data as it is generated. Ongoing epidemiological and genomic surveillance is imperative to identify viral determinants of transmission dynamics, monitor viral changes and adaptation, ensure accurate diagnosis, guide research on therapeutic targets, and refine public health strategies. It is our hope that this work will aid the multidisciplinary international efforts to understand and contain this expanding epidemic.

In memoriam: Tragically, five co-authors, who contributed greatly to public health and research efforts in Sierra Leone, contracted EVD and lost their battle with the disease before this manuscript could be published: Mohamed Fullah, Mbalu Fonnie, Alex Moigboi, Alice Kovoma, and S. Humarr Khan. We wish to honor their memory.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Office of the President of Sierra Leone (President E. Koroma, M. Jones, S. Blyden), the Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation (Minister M. Kargbo, B. Kargbo, M. A. Vandi, A. Jambai), the Kenema District Health Management Team, and the Lassa fever program for their efforts in outbreak response. We thank P. Cingolani, Y.-C. Wu, M. Lipsitch, S. Gunther, S. Baize, N. Wauquier, J. Bangura, V. Lungay, L. Hensley, J. Johnson, M. Voorhees, A. O'Hearn, R. Schoepp, L. Gaffney, J. Kuhn, S. C. Sealfon, J. B. Shapiro, C. Edwards, and Sabeti lab members for technical support and feedback. Supported by the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program (R.S.G.S.), NIH grant GM080177 (S. Wohl), NIH grant 1U01HG007480-01 and the World Bank (C.H.), European Union grant FP7/2007-2013 278433-PREDEMICS and European Research Council grant 260864 (A.R.), Natural Environment Research Council grant D76739X (G.D.), NIH grant 1DP20D006514-01, and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant HHSN272200900049C. Sequence data are available at NCBI (NCBI BioGroup: PRJNA257197). Sharing of RNA samples used in this study requires approval from the Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation.

Footnotes

Supplementary Materials: www.sciencemag.org/content/345/6202/1369/suppl/DCl

Materials and Methods

References (19–44)

References and Notes

- 1.Kuhn JH, et al. Biosecur Bioterror. 2011;9:361–371. doi: 10.1089/bsp.2011.0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke J. Bull World Health Organ. 1978;56:271–293. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baize S, et al. N Engl J Med. 2014 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoal404505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. 2014 www.who.int/csr/don/archive/disease/ebola/en/

- 5.Reynard 0, Volchkov V, Peyrefitte C. Med Sci. 2014;30:671–673. doi: 10.1051/medsci/20143006018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.See supplementary materials on Science Online

- 7.Towner JS, Sealy TK, Ksiazek TG, Nichol ST. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(suppl. 2):S205–S212. doi: 10.1086/520601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panning M, et al. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(suppl 2):S199–S204. doi: 10.1086/520600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malboeuf CM, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanchez A, Trappier SG, Mahy BW, Peters CJ, Nichol ST. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3602–3607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Volchkov VE, et al. Virology. 1995;214:421–430. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Volchkova VA, Dolnik 0, Martinez MJ, Reynard 0, Volchkov VE. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(suppl 3):S941–S946. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dudas G, Rambaut A. PL0S Curr Outbreaks. 2014;6 doi: 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.84eefe5ce43ec9dc0bf0670f7b8b417d. 10.1371/Currents.outbreaks.84eefe5ce43ec9dc0bf0670f7b8b417d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuhn J, Calisher CH, editors. Filoviruses: A Compendium of 40 Years of Epidemiological, Clinical, and Laboratory Studies. Springer; New York: 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schreiber MJ, et al. J Virol. 2009;83:4163–4173. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02445-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wertheim J0, Kosakovsky Pond SL. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:3355–3365. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho SY, Phillips MJ, Cooper A, Drummond AJ. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:1561–1568. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmes EC. J Virol. 2003;11:11296–11298. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.20.11296-11298.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.