Abstract

Chromatin interactions connect distal regulatory elements to target gene promoters guiding stimulus- and lineage-specific transcription. Few factors securing chromatin interactions have so far been identified. Here, by integrating chromatin interaction maps with the large collection of transcription factor-binding profiles provided by the ENCODE project, we demonstrate that the zinc-finger protein ZNF143 preferentially occupies anchors of chromatin interactions connecting promoters with distal regulatory elements. It binds directly to promoters and associates with lineage-specific chromatin interactions and gene expression. Silencing ZNF143 or modulating its DNA-binding affinity using single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as a surrogate of site-directed mutagenesis reveals the sequence dependency of chromatin interactions at gene promoters. We also find that chromatin interactions alone do not regulate gene expression. Together, our results identify ZNF143 as a novel chromatin-looping factor that contributes to the architectural foundation of the genome by providing sequence specificity at promoters connected with distal regulatory elements.

Chromatin interactions can connect distal regulatory elements to

promoters via protein factors, but few such factors have been identified. Here, the

authors show that zinc-finger protein ZNF143 is a sequence-specific chromatin-looping

factor that connects promoters with distal regulatory elements.

Chromatin interactions can connect distal regulatory elements to

promoters via protein factors, but few such factors have been identified. Here, the

authors show that zinc-finger protein ZNF143 is a sequence-specific chromatin-looping

factor that connects promoters with distal regulatory elements.

Cell fate determination relies on lineage-specific transcription programs set by master transcription factors acting on distal regulatory elements, such as enhancers, and proximal gene promoters1. Distal regulatory elements can be separated from their target promoter(s) over large genomic distances. They are brought in close proximity to one another through chromatin interactions/loops, defining the chromatin architecture of the genome1. Close to 60% of chromatin interactions are cell type specific2,3 and significantly correlate with lineage-specific transcriptional programs2. These chromatin interactions form during cellular differentiation4,5 and set the stage for stimulus-specific transcriptional responses6. Although a role for non-coding RNA was proposed, recent findings suggest that chromatin interactions rely on DNA sequences. For instance, a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) associated with pigmentation modulates a chromatin interaction between a distal enhancer and the promoter of the oculocutaneous albinism II (OCA2) gene7. Similarly, mutations in the DNA recognition sequence for the CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) impinge on the formation of chromatin interactions8.

CTCF is known to directly regulate the formation of chromatin interactions in partnership with the cohesin and/or mediator complexes9. It occupies distal regulatory elements located close to enhancers5,10,11 and defines the boundaries of topological domains when paired with the cohesin complex10,12. Genomic regions bound by the mediator and cohesin complexes anchor interactions regulating lineage-specific gene expression found within topological domains10. Although the mediator and cohesin complexes lack DNA-binding domains, their recruitment to the chromatin commonly coincides with CTCF13,14 or other transcription factors such as the oestrogen receptor alpha15. However, CTCF and oestrogen receptor alpha bind chromatin far from promoter regions15,16 and cohesin-binding sites found at promoters relate to tissue-specific transcription15. This suggests the existence of a yet-to-be identified promoter-bound DNA recognition factor(s) capable of specifying the target gene promoter(s) of distal regulatory elements.

Here we report the enrichment of the zinc-finger protein ZNF143 at anchors of chromatin interactions connecting promoters with distal regulatory elements. Our results indicate that ZNF143 is directly recruited to the promoter of genes engaged in chromatin interactions, where it binds to its DNA recognition sequence. We also show that modulating ZNF143 binding by SNPs directly impacts chromatin interaction frequencies. This reveals the dependency of chromatin interactions on DNA sequence and implies that chromatin interactions can be affected by genetic alterations (genetic variants or mutations) associated with inherited traits and diseases. Overall, our results demonstrate that ZNF143 is a new factor controlling the formation of chromatin interactions.

Results

ZNF143 binds promoters and forms distal phantom events

CTCF and cohesin complex proteins form a cluster distinct from other transcription factors, especially those bound at gene promoters. To identify the transcription factor(s) involved in securing chromatin interactions between promoters and distal regulatory elements, we first looked for factors that bridge promoter factors with the CTCF-cohesin cluster. For this, we correlated the chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-seq signal intensities of more than 70 transcription factors profiled by the Encyclopedia of DNA elements (ENCODE)17 project across all regions of open chromatin (see Methods) in GM12878 or K562 cells. In agreement with previous reports, we find that ZNF143 is unique because it associates with the ‘CTCF-cohesin’ cluster18 in both cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 1). However, we show that its genome-wide-binding profile is most similar to promoter-bound factors (Supplementary Fig. 1). In agreement, ZNF143’s correlation with the CTCF-cohesin cluster relies on its weakest binding sites (Fig. 1a), found primarily at distal regulatory elements defined by the ‘CTCF-rich’ chromatin state19 (Fig. 1b). The strongest ZNF143-binding sites map to promoters (Fig. 1b) bound by RNA polymerase II (POL2; Fig. 1a) and other promoter-associated factors, such as the TATA-binding protein (TBP) and the TBP-associated protein, together forming a ‘promoter’ cluster (Supplementary Fig. 1). This agrees with the reported enrichment of ZNF143’s DNA recognition motif at promoters20. These same strongest ZNF143-binding sites associate with weak CTCF and cohesin binding (Fig. 1a). Of all the transcription factors profiled using ChIP-seq by the ENCODE project, ZNF143 is the only one correlated with the ‘CTCF-cohesin’ and the ‘promoter’ clusters in both GM12878 and K562 cells (Supplementary Fig. 1) indicating its potential role in mediating chromatin interactions involving gene promoters.

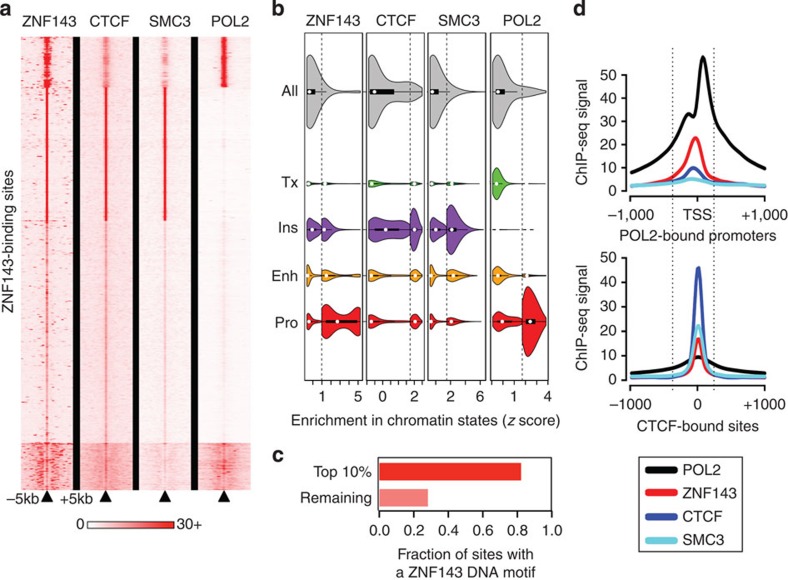

Figure 1. ZNF143 binds promoters and occupies CTCF and cohesin bound distal regulatory elements.

(a) A heatmap of the signal intensities from ChIP-seq assays against ZNF143, CTCF, SMC3 and POL2 across all ZNF143-binding sites (± 5 kilobases (kb)) called in GM12878 cells. (b) Violin plots of the signal intensities from ChIP-seq assays against ZNF143, CTCF, SMC3 and POL2 at their respective binding sites and the distributions of these sites across chromatin states defined by epigenetic modifications. The violin plots are split to show the distribution of the top decile of each factor separately. Enh, Enhancer; Ins, Insulator; Pro, Promoter; Tx, Transcription. (c) A bar plot revealing the fraction of ZNF143 chromatin-binding sites in GM12878 cells that harbour its DNA recognition sequence. (d) The average binding intensity of ZNF143, CTCF, SMC3, and POL2 at POL2-bound promoters (top) and CTCF-binding sites (bottom).

Enriched motif analysis reveals that more than 80% of the strongest ZNF143-binding sites harbour its DNA recognition motif, while it is found in less than 30% of weak binding sites (Fig. 1c). The presence of the motif suggests that ZNF143 is recruited directly to promoters where it binds next to POL2 (Fig. 1d). These results agree with its role as a promoter-bound transcriptional activator20,21,22,23,24. The fact that weak ZNF143-bound sites rarely harbour its DNA recognition motif and align with CTCF and the cohesin complex (Fig. 1b,d), suggests that ZNF143 indirectly binds distal regulatory elements. Although tethering mechanisms allow indirect protein binding to the chromatin25, phantom binding events26,27 resulting from the use of crosslinked cells in ChIP-seq assays where chromatin interaction are stabilized was recently proposed to account for indirect transcription factor binding to the chromatin. Strong ZNF143 binding at sites deprived of its recognition motifs may arise from chromatin interactions from a single enhancer, such as the locus control region (LCR) at the β-globin gene cluster (see below), to multiple gene promoters. Together our results support the direct binding of ZNF143 at promoters and indirect binding to CTCF and the cohesin complex bound distal regulatory elements, which may arise due to chromatin interactions.

ZNF143 occupies the anchors of chromatin interactions

A central feature of chromatin-looping factors is that they occupy anchors of chromatin interactions3. High-resolution (~4 kilobases (kb)) genome-scale maps of chromatin interactions generated from carbon-copy chromatin conformation capture (5C) assays reveal 1,187 and 1,726 intrachromosomal pairs of chromatin interaction anchors in GM12878 and K562 cells, respectively3. Importantly, these chromatin interactions are specific to promoters looping with distal regulatory elements3. Using these data, we determined the proportion of ZNF143-binding sites at chromatin interaction anchors in comparison with the expected overlap calculated using 1,000 random-matched binding sets (RMBSs; see Methods). This revealed the significant enrichment of ZNF143 at chromatin interaction anchors in both GM12878 (P=1.93 × 10−13) and K562 cells (P=3.7 × 10−12; Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2a). This analysis also reveals the enrichment of CTCF and SMC3 at chromatin interaction anchors in GM12878 and K562 cells (P=3.28 × 10−12 and P=3.91 × 10−12 for GM12878 cells and P=6.09 × 10−14, P=2.50 × 10−6 for K562 cells, respectively; Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2a). Nominal significance was detected for RAD21 (P=0.0475 and P=2.01 × 10−4 for GM12878 and K562 cells, respectively; Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2a). None of the seven additional factors (P300, ZNF384, BHLHE40, MAZ, MXI1, TBP and COREST) significantly enriched at chromatin interaction anchors (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2a) share the symmetrical nucleosome positioning or correlation with the ‘CTCF-cohesin’ cluster reported for ZNF143 (refs 17, 18, 28) (Supplementary Fig. 1a). These results agree with recent reports of ZNF143 enrichment within the anchors of chromatin interactions called by paired-end tag sequencing (ChIA-PET) and HiC29,30.

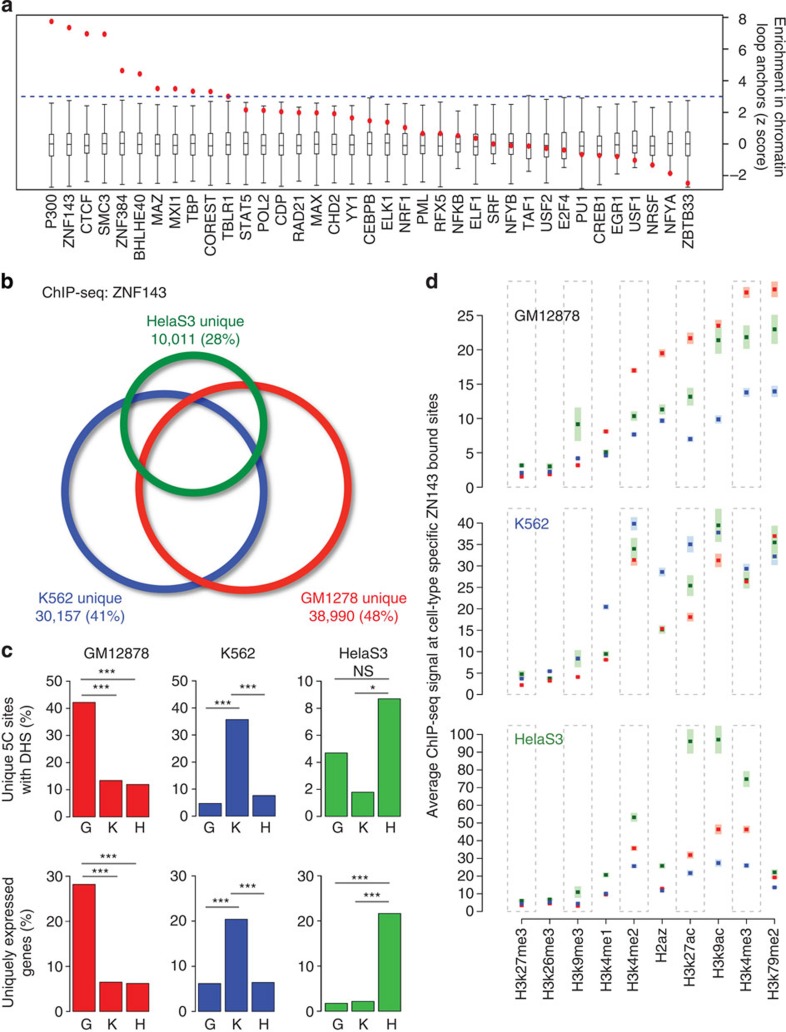

Figure 2. ZNF143 preferentially binds at chromatin interaction anchors.

(a) ZNF143-binding sites across the genome are enriched within the anchors of chromatin interactions reported in 5C assays. The normalized enrichment of ZNF143 and other transcription factors at both ends (anchors) of chromatin loops identified by 5C assays in GM12878 cells is shown. Box plots represent the normalized null distribution derived from the comparison between chromatin interactions and 1,000 RMBSs. Red dots indicate the observed per cent overlap of the transcription factor-binding sites within both 5C interaction anchors value relative to the generated null distribution represented as z scores. (b) Venn diagram depicting shared versus cell type-specific ZNF143-binding sites identified by ChIP-seq assays in GM12878, K562 and HelaS3 cells. (c) The above panel shows the percentage of cell type-specific chromatin interactions defined by 5C assays that harbour a DNaseI hypersensitivity site (DHS) bound by ZNF143 specifically in GM12878, K562 or HelaS3 cells. The bottom panel represents the proportion of promoters (± 2.5 kilobases (kb) from the transcription start site) of genes uniquely expressed in GM12878, K562 or HelaS3 bound by ZNF143 specific to one of these cell lines (G: GM12878, K: K562, H: HelaS3). The P value is derived from a χ2-test; (NS) not significant; *P≤0.05; ***P≤0.001. (d) Signal intensities for 10 different epigenetic modifications profiled by ChIP-seq in GM12878 (red), K562 (blue) and HelaS3 (green) cells across the unique top decile ZNF143-binding sites reported in GM12878 (top panel), K562 (middle panel) and HelaS3 (bottom panel) cells. The shaded area represents the s.e.m.

Considering that different cell types have distinct chromatin architectures, we assessed whether ZNF143-binding events correspond with cell type-specific chromatin interactions and gene expression. First, we compared the ZNF143-binding sites called in GM12878, K562 and HelaS3 cells. This revealed thousands of cell type-specific sites (Fig. 2b) and is similar to what is observed for CTCF and cohesin31,32. Comparing cell type-specific ZNF143-binding sites with chromatin interactions unique to GM12878, K562 or HelaS3 cells revealed that ZNF143 binding directly relates to cell type-specific chromatin interactions (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 2b). Epigenetic modifications, such as the mono- and dimethylation of lysine 4 on histone 3 (H3K4me1 and H3K4me2, respectively) may contribute to the cell type specificity of ZNF143, since these modifications can assist transcription factors binding and relate to cell type-specific binding profiles33,34,35. In agreement, the strongest cell type-specific ZNF143-binding sites harbour epigenetic modifications typical of active chromatin19,36, namely histone 3 lysine 4 monomethylation (H3K4me1), H3K4me2, histone 3 lysine 27 acetylation (H3K27ac) and the histone variant H2A.Z (Fig. 2d). Focusing on genes uniquely expressed in GM12878, K562 or HelaS3 cells reveals that cell type-specific ZNF143 binding correlates with differential gene expression (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 2c).

The cell type-specific association between ZNF143 binding, chromatin interactions and gene expression is exemplified by the LCR found ~50 kb upstream of the β-globin gene cluster. The promoters of the β-globin genes (haemoglobin delta (HBD) and haemoglobin gamma A (HBG1)) are bound by ZNF143 only in K562 cells (Supplementary Fig. 2e). The LCR harbours a single ZNF143-binding site shared between GM12878, K562 and HelaS3 cells (Supplementary Fig. 2e). Using an intercellular feature correlation (IFC) tool (see Methods), we predicted interactions between the LCR and the promoter of the HBD and HBG1 genes in K562 but not in GM12878 or HelaS3 cells (Supplementary Fig. 2d). Chromatin conformation capture (3C) assays confirmed that chromatin interactions connect the LCR and the promoter of the HBD and HBG1 genes only in K562 cells (Supplementary Fig. 2d). This agrees with these genes being expressed exclusively in K562 cells (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Data 1). Chromatin interactions predicted in all three cell lines for a ubiquitously expressed gene, such as the one connecting the TBL1XR1 promoter to an ~160 kb upstream regulatory element, validate by 3C assays in all cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 2e). These results support the preferential binding of ZNF143 at chromatin interaction anchors, including cell type-specific anchors related to lineage-specific transcriptional programs.

ZNF143 is required for chromatin interactions

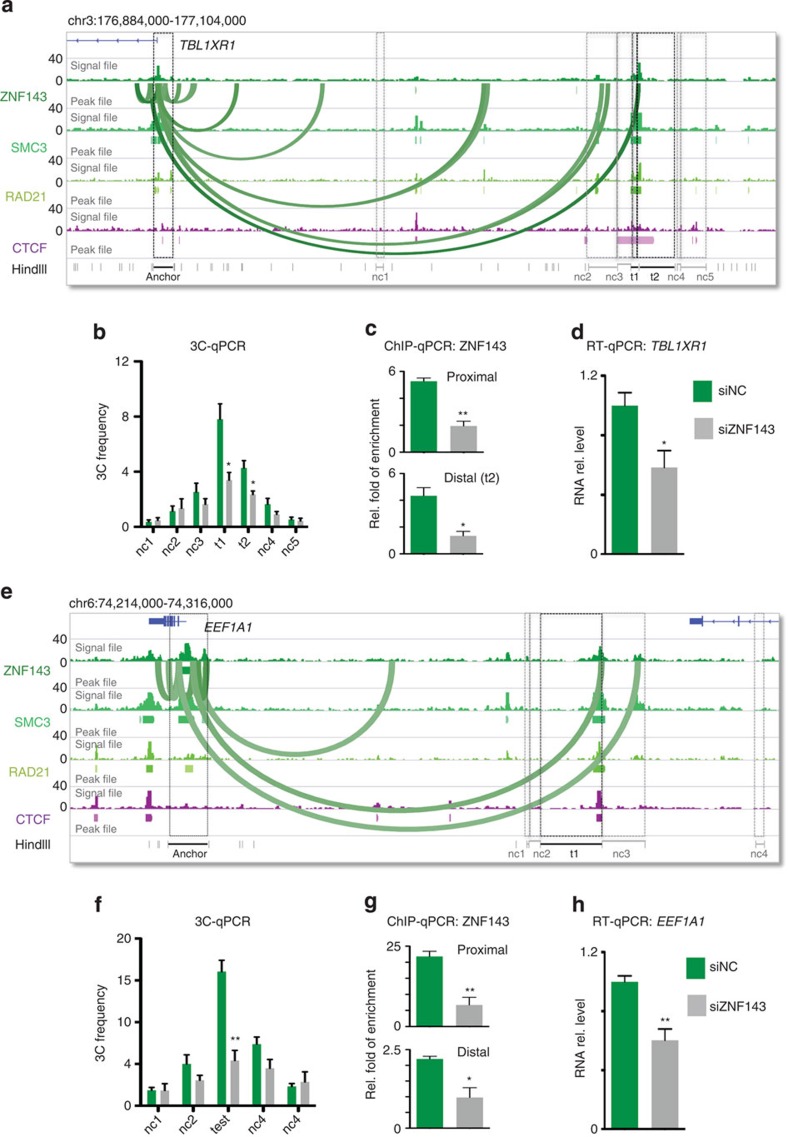

To directly assess the requirement of ZNF143 for the formation of chromatin interactions between promoter and distal regulatory elements, we determined the impact of modulating ZNF143 binding to the chromatin on the frequency of chromatin interactions. We first focused on the chromatin interactions predicted by IFC in HelaS3 cells between distal regulatory elements and the promoter of the transducing beta-like 1 X-linked receptor (TBL1XR1) or the eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1-alpha (EEF1A1) genes (Fig. 3). Using 3C assays anchored at the promoters of the TBL1XR1 or EEF1A1 genes, we validated a series of predicted chromatin interactions (Fig. 3a,b,e,f). Depletion of ZNF143 using small-interfering RNA (siRNA)-based silencing in HelaS3 cells significantly decreased the frequency of these chromatin interactions (Fig. 3b,f). Consistently, a reduction in ZNF143 binding at the distal regulatory elements and promoters of the TBL1XR1 and EEF1A1 genes was observed (Fig. 3c,g), as was a decrease in the expression of both the TBL1XR1 and EEF1A1 genes (Fig. 3d,h). Overall, these results support a role for ZNF143 in chromatin loop formation.

Figure 3. ZNF143 is required for the formation of chromatin interactions.

(a) Chromatin interactions predicted by the IFC analysis anchored on the TBL1XR1 gene promoter are represented by Bezier curves. Signal and peak files for ZNF143, SMC3, RAD21 and CTCF defined by ChIP-seq assays in HelaS3 are presented. Test (t1 and t2) regions (black boxes) and negative control (nc1–5) regions (grey boxes) are shown. (b) 3C assays anchored at the TBL1XR1 gene promoter reveal the interactions frequencies at a number of predicted chromatin interactions in HelaS3 cells transfected with the siRNA control (green bars). These interactions are diminished on silencing ZNF143 (grey bars). (c) ChIP-qPCR assays against ZNF143 at the TBL1XR1 gene promoter (proximal) and distal site (t1) mapping to the chromatin interactions are presented in HelaS3 cells transfected with the siRNA control (green bars). The ChIP signal is diminished on silencing ZNF143 (grey bars). (d) RT–qPCR assays reveal the expression of the TBL1XR1 gene in HelaS3 cells transfected with the siRNA control (green bars) and on silencing ZNF143 (grey bars). (e–h) Similar to a–d but for the EEF1A1 gene locus The P value is derived from a t-test; *P≤0.05; **P≤0.01. t1=test region (black boxes); nc1–4=negative control regions (grey boxes). Error bars indicate the s.e.m. Experiments were performed in triplicate. rel., relative.

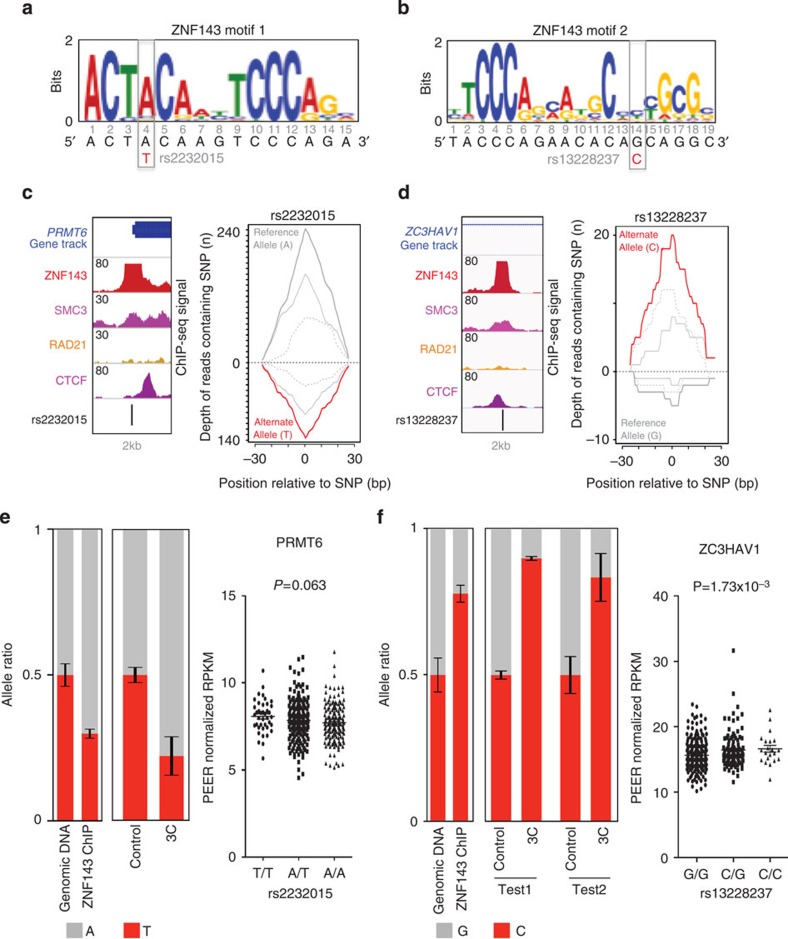

The global depletion of ZNF143 induced by silencing its expression using siRNAs can indirectly impact chromatin interactions. To bypass this limitation, we identified SNPs inducing allele-specific binding of ZNF143 to the chromatin and determined their impact on chromatin interactions. We first identified SNPs heterozygous in GM12878 cells found at ZNF143-bound sites using the genotype data provided by the 1,000 genomes project37. Using our allele-specific binding from ChIP-seq (ABC) tool (see Methods), we then identified 28 SNPs displaying an allele-specific bias in the ZNF143 ChIP-seq reads from GM12878 cells (P<0.005). Two SNPs, rs2232015 and rs13228237, located within the promoter of the protein arginine methyltransferase 6 (PRMT6) and the first intron of the zinc-finger CCCH-type antiviral 1 (ZC3HAV1) genes, respectively (Fig. 4), were in close proximity (~300 bp) to restriction sites for HindIII (enzyme used in the 3C assay). The rs2232015 SNP maps to the fourth position of the ZNF143 DNA recognition sequence (motif 1; Fig. 4a) the most prominent motif found within ~85% of the top 500 sites. The rs13228237 SNP changes the fourteenth position of a reported extension of a ZNF143 DNA recognition sequence22,38 (motif 2; Fig. 4b), which is found within ~25% of the top 500 sites. Consistent with the observation that the actual ZNF143-binding sites are located at gene promoters, ~43% and ~76% of gene promoters (±2.5 kb of the transcription start site) bound by ZNF143 were found to contain motif 1 or motif 2 (motif P values <1 × 10−4) in GM12878 cells, respectively. Interesting, motif 2 appears to be the most prominent ZNF143 motif found at gene promoters and most closely resembles the ZNF143 motif characterized using in vitro methods22,39. The imposed changes to the DNA sequence based on the position-weighted matrix predict preferential binding of ZNF143 to the reference A and the variant C allele of the rs2232015 and rs13228237 SNPs, respectively, compared with the other alleles (Fig. 4a,b). In agreement, 242 reads from the ZNF143 ChIP-seq data, mapping to the rs2232015 SNP, contain the reference A allele and 136 reads contain the variant T allele (P=5.47 × 10−8; Fig. 4c). Likewise, of the 25 reads mapping to the rs13228237 SNP, five contain the reference G allele and 20 contain the variant C allele (P=4.08x10−3; Fig. 4d). Importantly, the signal intensity of the ZNF143-binding site containing the rs13228237 SNP is high (n=175) indicating that this SNP falls within the centre of the inferred ZNF143-binding site and between the positive and negative strand peaks of the unprocessed ChIP-Seq reads (Fig. 4d). Allele-specific ChIP-quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays against ZNF143 in GM12878 cells validated the predicted allelic imbalance for both SNPs (Fig. 4e,f and Supplementary Fig. 3). Consistent with ZNF143 being directly responsible for chromatin loop formation, the decreased binding of ZNF143 to the chromatin caused by the variant allele at the rs2232015 SNP leads to a corresponding allele-specific reduction of the chromatin interaction frequency measured by 3C assays between the PRMT6 promoter and a distal regulatory element ~85 kb away (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. 3). Interestingly, the rs2232015 SNP modulates a portion of the ZNF143 recognition motif that is shared with THAP11 and recently shown in vitro to be dispensable for ZNF143 binding22. These results, while revealing that ZNF143 is required, may indicate that a complex of factors specify chromatin interactions. Similarly, the increased binding of ZNF143 to the chromatin caused by the variant C allele of the rs13228237 SNP leads to an increase in the chromatin interaction frequency between the first intron of the ZC3HAV1 gene and two distal regulatory elements located ~200 kb away (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 3). Interestingly, this ZNF143-binding site is located ~14 kb from the transcription start site of the ZC3HAV1 gene and may represent an unknown isoform of ZC3HAV1 gene. Consistently, a transcription start site was predicted from 5′ cap analysis of gene expression data 89 bp from the rs13228237 in GM12878 by the ENCODE project (Supplementary Fig. 4). Expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) analysis of the rs2232015 and rs13228237 SNPs using RNA-Seq data from lymphoblastoid cells (n=373) (ref. 40) genotyped as part of the 1,000 Genomes Project41 reveals that the ZC3HAV1 expression is modulated by the rs13228237 SNP in lymphoblastoid cells (P=1.73 × 10−3; Fig. 4f). However, the rs2232015 SNP is not significantly associated with the expression of the PRMT6 gene (P=0.063; Fig. 4e). This coincides with a repressed element and poised promoter chromatin state at the distal regulatory element looping to the PRMT6 promoter in the GM12878 cells (Supplementary Fig. 5), which contrasts with the active state at regulatory elements looping to the ZC3HAV1 promoter (Supplementary Fig. 5). Interestingly, the rs2232015 SNP is in strong linkage disequilibrium (r2≥0.95) with two reported eQTLs captured by the rs1762509 and rs9435441 SNPs42,43. The rs1762509 and rs9435441 SNPs lead to allele-specific expression of the PRMT6 gene within the liver cells and monocytes, respectively42,43. Consistently, the interacting distal regulatory element looping to the PRMT6 promoter is in an active state within liver cells (Supplementary Fig. 5). This suggests that chromatin interactions are not sufficient to impact gene expression, as recently reported at the β-globin locus44 and that ZNF143 role in loop formation is not dependent on gene transcription.

Figure 4. Genetic variants modulate ZNF143 binding to the chromatin changing the frequency of chromatin interactions.

(a) Position of the rs2232015 SNP with regards to one of the ZNF143 DNA recognition sequences (motif 1). (b) Position of the rs13228237 with regards to the second ZNF143 DNA recognition sequence (motif 2). (c) Location of the rs2232015 SNP with respect to the binding profiles of ZNF143, SMC3, RAD21 and CTCF in GM12878 cells (left panel). Allele-specific bias in the ZNF143 ChIP-seq reads at the rs2232015 SNP is shown (right panel). The number of reads mapping to the positive strand (solid grey) and negative strand (dashed grey) are also shown for both the reference and variant allele. (d) Same as for c but for the rs13228237 SNP. (e) Allele-specific ChIP-qPCR against ZNF143 and 3C-qPCR results at the rs2232015 SNP in GM12878 cells are presented. Bar charts illustrate the bias in the allele ratio for the rs2232015 SNP in both assays. Error bars indicate the s.e.m. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Results from the eQTL analysis in lymphoblastoid cells are presented for the PRMT6 gene. Expression values are plotted by genotype. Expression values are presented as probabilistic estimation of gene expression residuals (PEER) normalized reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (RPKM). (f) Same as in e but relevant to the rs13228237 SNP. Error bars indicate the s.e.m.

Discussion

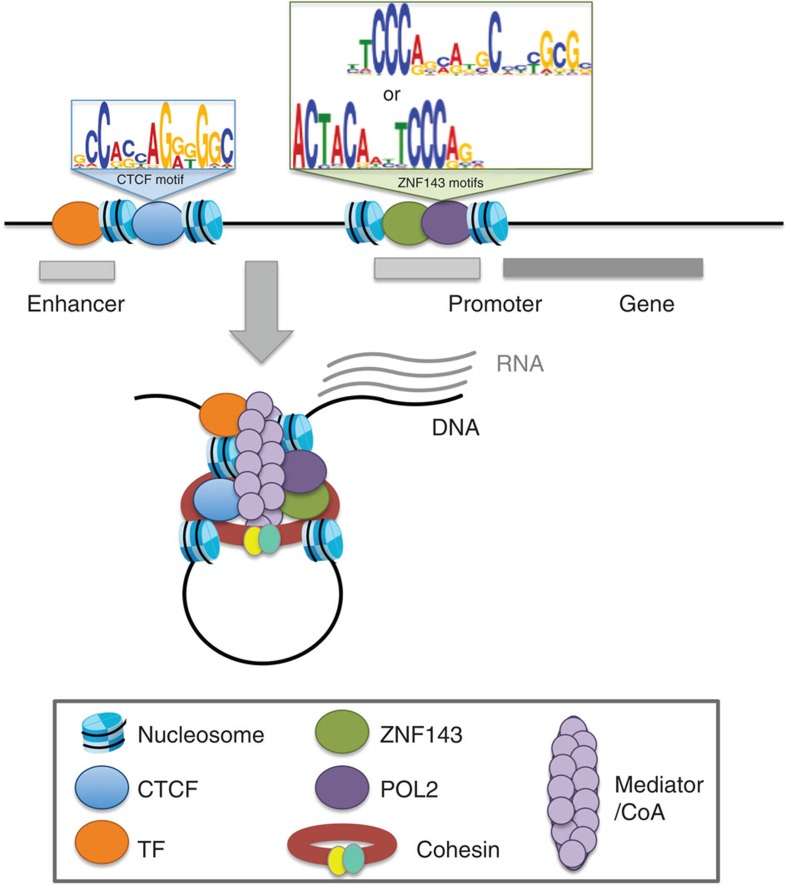

Cellular identity is dependent on lineage-specific transcriptional programmes set by master transcription factors acting at regulatory elements that communicate with one another through chromatin interactions1. Recently, the ENCODE project17 observed well-positioned and symmetrical nucleosomes flanking the binding sites of CTCF, RAD21 and SMC3, which contrasted the variability observed surrounding the binding sites of other transcription factors with the exception of ZNF143 (ref. 17). In agreement with this observation representing a unique feature of chromatin-looping factors, we demonstrate that ZNF143 is required at promoters to stimulate the formation of chromatin interactions with distal regulatory elements (Fig. 5). This aligns with its reported role favouring POL2 occupancy at gene promoters22 and in the assembly of the pre-initiation complex23. The fact that ZNF143 is ubiquitously expressed21 suggests that ZNF143 may be a regulator of the architectural foundations of cell identity. Although the mechanisms accounting for cell type-specific ZNF143-binding profiles are unknown, chromatin interactions were recently reported to be set early during lineage commitment6. In agreement, ZNF143 is required for zebrafish embryo development45, for stem cell identity and for the self-renewal ability of human embryonic stem cells46,47. Altogether, our results reveal that ZNF143 directly binds promoters to secure chromatin interactions with distal regulatory elements. ZNF143 provides a sequence-dependent mechanism for the formation of chromatin interactions that can be modulated by genetic variants underlying inherited traits and diseases.

Figure 5. Schematic representation of chromatin interactions involving gene promoters.

ZNF143 contributes the formation of chromatin interactions by directly binding the promoter of genes establishing looping with distal element bound by CTCF.

Methods

Co-localization of transcription factor binding

Focusing on DHS sites identified by the Hotspots algorithm48 in either GM12878 or K562 cells, we extracted the ChIP-seq signal from model shifted wiggle files49 for ≥75 transcription factors profiled in these cell lines. All these data sets are available through the ENCODE project17,50. Transcription factor ChIP-seq files were downloaded from the ENCODE Data Coordination Center website (http://genome.ucsc.edu/ENCODE/), specifically from the ENCODE/Stanford/Yale/USC/Harvard/ (GEO accession numbers: GSM935277; GSM935283; GSM935294; GSM935301; GSM935309 to GSM935311; GSM935316; GSM935319; GSM935330 to GSM935332; GSM935336 to GSM935338; GSM935340; GSM935343 to GSM935345; GSM935349; GSM935355; GSM935356; GSM935358; GSM935361; GSM935363; GSM935368; GSM935371 to GSM935378; GSM935385; GSM935386; GSM935388; GSM935390 to GSM935394; GSM935401; GSM935402; GSM935407; GSM935409 to GSM935415; GSM935417; GSM935419; GSM935420; GSM935422; GSM935425; GSM935427 to GSM935431; GSM935433; GSM935439; GSM935442; GSM935450; GSM935464; GSM935466 to GSM935475; GSM935478 to GSM935483; GSM935487; GSM935488; GSM935490; GSM935492; GSM935494 to GSM935497; GSM935499 to GSM935507; GSM935516; GSM935518; GSM935520; GSM935521; GSM935524; GSM935532; GSM935539 to GSM935541; GSM935544; GSM935546 to GSM935549; GSM935556 to GSM935559; GSM935562; GSM935564; GSM935565; GSM935568; GSM935569; GSM935573 to GSM935576; GSM935583; GSM935594; GSM935595; GSM935597 to GSM935602; GSM935608; GSM935611 to GSM935613; GSM935616; GSM935618; GSM935631 to GSM935634; GSM935642; GSM935645; GSM935651 to GSM935653; GSM1003602 to GSM1003605; GSM1003608 to GSM1003611; GSM1003616; GSM1003617; GSM1003620 to GSM1003622; GSM1003625; GSM1003634 GSM803338; GSM803341; GSM803342; GSM803346; GSM803347; GSM803349 to GSM803352; GSM803355; GSM803356; GSM803362; GSM803363; GSM803378 to GSM803380; GSM803383; GSM803384; GSM803386 to GSM803392; GSM803401; GSM803402; GSM803406 to GSM803408; GSM803410; GSM803411; GSM803413; GSM803414; GSM803416; GSM803420; GSM803431; GSM803434; GSM803436; GSM803439; GSM803440 to GSM803443; GSM803446; GSM803447; GSM803468 to GSM803471; GSM803473; GSM803477; GSM803485; GSM803494; GSM803496; GSM803504; GSM803505; GSM803508 to GSM803511; GSM803515; GSM803520; GSM803523 to GSM803525; GSM803531 to GSM803534; GSM803537; GSM803538; GSM803540; GSM1010721; GSM1010722; GSM1010729 to GSM1010732; GSM1010744; GSM1010745; GSM1010760; GSM1010771; GSM1010779; GSM1010780; GSM1010782; GSM1010820; GSM1010850; GSM1010867; GSM1010877; GSM1010878; GSM1010881; GSM1010890; GSM1010893 to GSM1010895; GSM1010906) production laboratories. We converted all.bam files to wiggle files (.wig files) using MACs 1.4 (ref. 49). DHS sites called by the Hotspots algorithm for each cell line were downloaded from the ENCODE Data Coordination Center website (http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg19/encodeDCC/wgEncodeUwDnase/).

The maximum signal intensity value of each transcription factor across all DHS sites created the vectors used for the Pearson correlation (r) calculation. Hierarchical clustering was then performed on the resulting correlation matrix using average linkage and 1−r as the distance metric. The input control was included in the analysis as a control. All transcription factors with binding profiles that clustered with the control were dismissed from the final figure. Since we correlated the binding profiles across regions of open chromatin, this analysis not only removes failures but also factors that bind to heterochromatin. This analysis was performed using the first replicate for all transcription factors.

Transcription factor-binding sites across chromatin states

The chromHMM51-derived genomic annotations of chromatin states in GM12878 and K562 cell lines were downloaded from the UCSC genome browser website (http://genome.ucsc.edu). The intersection between genomic annotations and the summit of the binding sites for transcription factors were performed using the BEDTools software package52.

Enrichment of transcription factor binding at looping sites

Carbon-copy chromatin conformation capture (5C) data sets generated in GM12878, K562 and HelaS3 cell lines were downloaded from the ENCODE Data Coordination Center website (http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg19/encodeDCC/wgEncodeUmassDekker5C/) (GEO Accession numbers: GSM970499, GSM970500, GSM970497).

The proportion of paired-end tags (PET) where both interacting anchors overlap transcription factor-binding sites (peak files) was determined using a custom Perl script. The significance of this overlap was compared with that of 1,000 simulated random-matched binding sets (RMBSs) for each transcription factor. Each simulated RMBS matched the experimental set in chromosome distribution, absolute number, and size of the binding sites. We randomly selected binding sites of equal or greater size, trimming larger sites, from the complete set of all possible binding sites defined by the union of all reported binding sites for all transcription factors in a given cell line provided by the ENCODE project. Therefore, the probability of selecting a given binding site was equal to its observed frequency in all of the profiled transcription factors. Two-tailed P values were calculated from z scores using the generated null distributions.

This analysis was performed using the first replicate for all transcription factors and when multiple groups profiled the same factor the first replicate from the larger data set was used.

Identification of uniquely expressed genes

RNA-Seq data for the three cell lines, in four replicates, were downloaded from NCBI gene Expression Omnibus (GEO accession numbers: GSM591661; GSM591673; GSM591664; GSM591664; GSM958728; GSM958730; GSM591670; GSM591671; GSM591682; GSM591659; GSM765402; GSM767848; GSM883635; GSM672833; GSM591666; GSM591668; GSM591679; GSM591660; GSM958729, Supplementary Table 1). Reads were aligned to the human genome hg19 using the TopHat software tool version 2 (ref. 53). To identify genes that are uniquely expressed in each of the three cell lines, we used the Cufflinks software tool version 2.1.1 (ref. 53). First, we filtered all genes that have an FPKM (fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped) value equal to 0 (no expression) in all three cell lines. Next we identified genes that are unique to each cell line (expressed in one cell line and not in the others) and genes found to be expressed in more than one cell line (commonly expressed genes). To identify differentially expressed genes between the three cell lines first, we did a one per one comparison (K562-HelaS3, K562-GM12878 and HelaS3-GM12878). Then we performed one per two comparisons to identify genes differentially expressed in one specific cell line compared with the others.

Predicting chromatin interactions

We predicted chromatin interaction using an intercellular feature correlation (IFC) approach similar to PreSTIGE (http://prestige.case.edu)54 and others19,55,56 to calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) between two DHS sites based on the DNaseI hypersensitivity signals generated by DNase-seq across all cell lines available by the ENCODE project (http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg19/encodeDCC/wgEncodeUwDnase/; GEO accession numbers: GSM736491 to GSM736639). To provide cell type specificity to the correlation analysis, we calculated the correlation coefficient, using DNase-seq data sets from all available cell lines, only at DHS sites identified by the hotspots algorithm48 for K562, GM12878 or HelaS3 independently. This provides for correlated DHS in K562, GM12878 or HelaS3 cells, respectively. We also restricted our analysis to ±500 kb surrounding the DHS anchor site that contained our region of interest (promoter or ZNF143-binding site).

Allele-specific transcription factor binding

To call SNPs displaying an allele-specific bias in transcription factor binding, we developed a software tool, which we refer to as allele-specific binding from ChIP-seq (ABC). ABC directly compares differences in read abundance between reference and variant alleles using a binomial probability test at heterozygous SNPs identified by genotyping. The genotype information for the GM12878 (NA12878) cell line was downloaded from the 1000 Genomes Project’s website (www.1000genomes.org). The ABC approach relies on the number of aligned reads and contains the highest power to detect an allelic imbalance on the edges of an identified binding site, or the maxima of each strand-specific peak, obtained from single-end reads based on technical biases created by short-read sequencing of the ends of ChIP fragments. Thus, ABC also aims to determine the location of a particular genetic variant within a given binding site by assessing the strand distribution of reads containing the two alleles, not to be confused with a strand bias test applied for genotyping algorithms57, since unlike genomic DNA the null expectation of equal coverage of a particular genetic variant by reads in both orientations is not held for reads derived from ChIP-seq assays. In addition, a position bias where the alleles of a genetic variant are not equally distributed along the length of the reads spanning it can be used to identify potential false-positive allele-specific binding or potential transcription factor repositioning events. ABC currently applies the Mann–Whitney U-test to assess a potential position bias. SNPs violating the position test are dismissed.

We restricted our analysis to heterozygous SNPs reported in GM12878 by the 1000 Genomes Project58. We prioritized SNPs mapping to the ZNF143 DNA recognition sequence. ABC was then employed to identify heterozygous SNPs leading to observable allele-specific biases in the sequencing reads obtained from ChIP-seq assays against ZNF143 within GM12878 cells. Finally, we filtered out SNPs found within repetitive regions and known segmental duplications because these variables can confound allele-specific analyses. The ABC code used to identify SNPs causing allele-specific binding can be accessed via GitHub (https://github.com/mlupien/ABC).

For the eQTL analysis, RNA-seq performed on lymphoblastoid cell lines from the 1,000 genomes project41 was obtained from Lappalainen et al.40 (EBI ArrayExpress accessions: E-GEUV-1, E-GEUV-2, E-GEUV-3). 373 European individuals from four populations (CEPH (CEU) Finns (FIN) British (GBR) and Toscani (TSI)) were stratified by SNP genotype. Probabilistic estimation of gene expression residuals PEER59 normalized reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (RPKMs) was associated with SNP genotype using linear regression.

Cell culture and transfection

GM12878, K562 and HelaS3 cells were grown in the RPMI (15% FBS), RMPI (10% FBS) and DMEM (10% FBS) media, respectively. For siRNA transfection, HelaS3 cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA (siNC) or siZNF143 using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Life Technologies, 13378). RNA was extracted 72 h after transfection using Qiagen RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, 74104). Pre-verified Silencer Select siRNAs (Life Technologies, s15192 and s15194) targeting ZNF143 was used: 5′- GCAGAUUGUUUUACAAGGA -3′ and 5′- CGGUCGGUCCUUUACAACA -3′. The GM12878 cells were obtained from the Coriell Institute for Medical Research (www.coriell.org; Catalogue ID GM12878). The K562 and HelaS3 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (www.atcg.org; ATCC number CCL-243 and ATCC number CCL-2.2, respectively).

Chromatin conformation capture (3C) assay

Chromosome Conformation Capture (3C) assays were performed as we previously described60. In brief, cells were counted and balanced to the same number (six million) before the 3C experiments to allow for comparison between different cell types or treatments. Cells were crosslinked and lysed. Chromatin was digested using 400 units of HindIII, followed by ligation with 4,000 units of T4 DNA ligase (NEB M0202S). Crosslinks were reversed by Qiagen proteinase K digestion. 3C products were purified by phenol–chloroform extraction, followed by qPCR. To control for random digestion, ligation and different primer efficiencies, randomly ligated DNA fragments within the tested loci were generated as previously described61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68. A standard curve for the Ct value of each 3C primer pair, anchor and bait, were generated from these randomly ligated DNA fragments. The 3C frequency of each primer pair was normalized to their corresponding standard curves and was further normalized to a loading control, primers hybridized to the genomic region of the RHO gene. Primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP followed by qPCR was performed as we previously described33. In brief, cells were crosslinked and lysed. Chromatin was sonicated and immunoprecipitated with anti-ZNF143 (Novus Biologicals H00007702-M01), followed by reverse crosslinking and DNA extraction. Four μg of anti-ZNF143 was used per five million cells in each experiment. For ChIP assays after siRNA treatment, cells were harvested 72 h after transfection. The number of cells was counted and balanced before ChIP. Primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Gene expression

RNA was isolated from HelaS3 cells using the QIAGEN RNeasy mini kit according to manufacturer’s recommendations. The purified RNA was treated with DNaseI to remove any possible DNA contamination. Reverse transcription PCR (RT) was performed to convert RNA into cDNA using an ABI high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit. The expression level of the queried genes was quantified by qPCR (RT–qPCR), as previously described60. Primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

In vivo allele-specific ChIP assay

In vivo allele-specific ChIP assays were performed as we previously described69. In brief, anti-ZNF143 immunoprecipitated and genomic input DNA was qPCR amplified using allele-specific mismatch amplification mutation assays primers70 to reveal the relative level of enrichment for each allele. To confirm the allele specificity, the PCR product from anti-ZNF143 immunoprecipitated and genomic input DNA were sequenced by Sanger sequencing. Primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

In vivo allele-specific 3C assay

In vivo allele-specific 3C assays were performed as we previously described69. A forward primer hybridizing to a sequence outside of each SNP and its closest HindIII restriction enzyme site was used to target each SNP region. A reverse primer hybridizing to a sequence close to the HindIII site from the distal site was used to target the distal interacting region. Each primer pair was used to amplify the HindIII 3C product from GM12878 cells. The amplified 3C products were assessed by qPCR, using allele-specific mismatch amplification mutation assay primers, to determine the relative level of each allele of the SNP involved in the chromatin loop. Allele specificity was further demonstrated through Sanger sequencing of the amplified 3C products.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Bailey, S. D. et al. ZNF143 provides sequence specificity to secure chromatin interactions at gene promoters. Nat. Commun. 6:6186 doi: 10.1038/ncomms7186 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-5, Supplementary Tables 1-2.

Genes uniquely expressed in G 12878, K562 and HelaS3 cells

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Benjamin Neel, Jason B. Wright and Mathieu Lemaire for discussions and Dr Philippe Carbon for providing the ZNF143 DNA recognition sequence matrix for the motif 2. We also acknowledge the ENCODE Consortium and the ENCODE production laboratories that generated the data sets provided by the ENCODE Data Coordination Center used in this manuscript. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number R01CA155004 (M.L.), R01CA160356 (P.C.S.) and the Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation (M.L.) supported the research reported in this publication. The research content reported is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding sources. M.L holds a young investigator award from the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research and a new investigator salary award from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR). S.D.B. is supported by a Knudson postdoctoral fellowship from the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions The study, or elements of, was conceived by S.D.B., R.C.-S., X.Z. and M.L and led by S.D.B., X.Z. and M.L. The biological assays were conducted by X.Z., K.D. and M.L. Computational analysis relevant to the distribution and enrichment of transcription factors across the genome and/or on chromatin interaction anchors were developed and/or implemented by S.D.B, X.Z., B.A.-Z., P.C.S and M.L. Computational approaches to identify the differential gene expression were performed by M.A. and B.H.-K. O.C. and P.C.S conducted the eQTL analyses. S.D.B., X.Z. and M.L. wrote the manuscript.

04/10/2018

The original HTML version of this Article had an incorrect volume number of 2; it should have been 6. This has now been corrected in the HTML; the PDF version of the Article was correct from the time of publication.

References

- Ong C. T. & Corces V. G. Enhancer function: new insights into the regulation of tissue-specific gene expression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12, 283–293 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G. et al. Extensive promoter-centered chromatin interactions provide a topological basis for transcription regulation. Cell 148, 84–98 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal A., Lajoie B. R., Jain G. & Dekker J. The long-range interaction landscape of gene promoters. Nature 489, 109–113 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser J. et al. Chromatin conformation signatures of cellular differentiation. Genome Biol. 10, R37 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagey M. H. et al. Mediator and cohesin connect gene expression and chromatin architecture. Nature 467, 430–435 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin F. et al. A high-resolution map of the three-dimensional chromatin interactome in human cells. Nature 503, 290–294 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser M., Kayser M. & Palstra R. J. HERC2 rs12913832 modulates human pigmentation by attenuating chromatin-loop formation between a long-range enhancer and the OCA2 promoter. Genome Res. 22, 446–455 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Splinter E. et al. CTCF mediates long-range chromatin looping and local histone modification in the beta-globin locus. Genes Dev. 20, 2349–2354 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong C. T. & Corces V. G. CTCF: an architectural protein bridging genome topology and function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 234–246 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips-Cremins J. E. et al. Architectural protein subclasses shape 3D organization of genomes during lineage commitment. Cell 153, 1281–1295 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure A. J. et al. Cohesin regulates tissue-specific expression by stabilizing highly occupied cis-regulatory modules. Genome Res. 22, 2163–2175 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon J. R. et al. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature 485, 376–380 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt K. S. et al. Cohesin mediates transcriptional insulation by CCCTC-binding factor. Nature 451, 796–801 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parelho V. et al. Cohesins functionally associate with CTCF on mammalian chromosome arms. Cell 132, 422–433 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt D. et al. A CTCF-independent role for cohesin in tissue-specific transcription. Genome Res. 20, 578–588 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T. H. et al. Analysis of the vertebrate insulator protein CTCF-binding sites in the human genome. Cell 128, 1231–1245 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham I. et al. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 489, 57–74 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie D. et al. Dynamic trans-acting factor colocalization in human cells. Cell 155, 713–724 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst J. et al. Mapping and analysis of chromatin state dynamics in nine human cell types. Nature 473, 43–49 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myslinski E., Gerard M. A., Krol A. & Carbon P. A genome scale location analysis of human Staf/ZNF143-binding sites suggests a widespread role for human Staf/ZNF143 in mammalian promoters. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 39953–39962 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myslinski E., Krol A. & Carbon P. ZNF76 and ZNF143 are two human homologs of the transcriptional activator Staf. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 21998–22006 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngondo-Mbongo R. P., Myslinski E., Aster J. C. & Carbon P. Modulation of gene expression via overlapping binding sites exerted by ZNF143, Notch1 and THAP11. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 4000–4014 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James Faresse N. et al. Genomic study of RNA polymerase II and III SNAPc-bound promoters reveals a gene transcribed by both enzymes and a broad use of common activators. PLoS Genet. 8, e1003028 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Negrete I. et al. Adhesion-dependent Skp2 transcription requires selenocysteine tRNA gene transcription-activating factor (STAF). Biochem. J. 436, 133–143 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldring N. et al. Multiple sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins mediate estrogen receptor signaling through a tethering pathway. Mol. Endocrinol. 25, 564–574 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer T. R. et al. DNase I-hypersensitive exons colocalize with promoters and distal regulatory elements. Nat. Genet. 45, 852–859 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J. et al. Chromatin immunoprecipitation indirect peaks highlight long-range interactions of insulator proteins and Pol II pausing. Mol. Cell 53, 672–681 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundaje A. et al. Ubiquitous heterogeneity and asymmetry of the chromatin environment at regulatory elements. Genome Res. 22, 1735–1747 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidari N. et al. Genome-wide map of regulatory interactions in the human genome. Genome Res. 24, 1905–1917 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao S. S. P. et al. A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell 159, 1665–1680 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou C., Dale R. & Dean A. Cell type specificity of chromatin organization mediated by CTCF and cohesin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 3651–3656 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prickett A. R. et al. Genome-wide and parental allele-specific analysis of CTCF and cohesin DNA binding in mouse brain reveals a tissue-specific binding pattern and an association with imprinted differentially methylated regions. Genome Res. 23, 1624–1635 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupien M. et al. FoxA1 translates epigenetic signatures into enhancer-driven lineage-specific transcription. Cell 132, 958–970 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heintzman N. D. et al. Histone modifications at human enhancers reflect global cell-type-specific gene expression. Nature 459, 108–112 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. et al. Androgen receptor regulates a distinct transcription program in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cell 138, 245–256 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barski A. et al. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell 129, 823–837 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abecasis G. R. et al. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature 491, 56–65 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. et al. Sequence features and chromatin structure around the genomic regions bound by 119 human transcription factors. Genome Res. 22, 1798–1812 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaub M., Krol A. & Carbon P. Flexible zinc finger requirement for binding of the transcriptional activator staf to U6 small nuclear RNA and tRNA(Sec) promoters. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 24241–24249 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappalainen T. et al. Transcriptome and genome sequencing uncovers functional variation in humans. Nature 501, 506–511 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin R. M. et al. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature 467, 1061–1073 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeller T. et al. Genetics and beyond—the transcriptome of human monocytes and disease susceptibility. PLoS ONE 5, e10693 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti F. et al. Identification, replication, and functional fine-mapping of expression quantitative trait loci in primary human liver tissue. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002078 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krivega I., Dale R. K. & Dean A. Role of LDB1 in the transition from chromatin looping to transcription activation. Genes Dev. 28, 1278–1290 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbig K. M., Lekven A. C. & Kunkel G. R. The transcriptional activator ZNF143 is essential for normal development in zebrafish. BMC Mol. Biol. 13, 3 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Fang F., Liou Y. C. & Ng H. H. Zfp143 regulates Nanog through modulation of Oct4 binding. Stem Cells 26, 2759–2767 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia N. Y. et al. A genome-wide RNAi screen reveals determinants of human embryonic stem cell identity. Nature 468, 316–320 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John S. et al. Chromatin accessibility pre-determines glucocorticoid receptor binding patterns. Nat. Genet. 43, 264–268 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome. Biol. 9, R137 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENCODE. A user’s guide to the encyclopedia of DNA elements (ENCODE). PLoS Biol. 9, e1001046 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst J. & Kellis M. ChromHMM: automating chromatin-state discovery and characterization. Nat. Methods 9, 215–216 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan A. R. & Hall I. M. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26, 841–842 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C. et al. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc. 7, 562–578 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corradin O. et al. Combinatorial effects of multiple enhancer variants in linkage disequilibrium dictate levels of gene expression to confer susceptibility to common traits. Genome Res. 24, 1–13 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurman R. E. et al. The accessible chromatin landscape of the human genome. Nature 489, 75–82 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffield N. C. et al. Patterns of regulatory activity across diverse human cell types predict tissue identity, transcription factor binding, and long-range interactions. Genome Res. 23, 777–788 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePristo M. A. et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat. Genet. 43, 491–498 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abecasis G. R. et al. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature 467, 1061–1073 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegle O., Parts L., Durbin R. & Winn J. A Bayesian framework to account for complex non-genetic factors in gene expression levels greatly increases power in eQTL studies. PLoS Comput. Biol. 6, e1000770 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Cowper-Sal Lari R., Bailey S. D., Moore J. H. & Lupien M. Integrative functional genomics identifies an enhancer looping to the SOX9 gene disrupted by the 17q24.3 prostate cancer risk locus. Genome Res. 22, 1437–1446 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolhuis B., Palstra R. J., Splinter E., Grosveld F. & de Laat W. Looping and interaction between hypersensitive sites in the active beta-globin locus. Mol. Cell 10, 1453–1465 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright J. B., Brown S. J. & Cole M. D. Upregulation of c-MYC in cis through a large chromatin loop linked to a cancer risk-associated single-nucleotide polymorphism in colorectal cancer cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 1411–1420 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palstra R. J. et al. The beta-globin nuclear compartment in development and erythroid differentiation. Nat. Genet. 35, 190–194 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker J. The three ‘C’ s of chromosome conformation capture: controls, controls, controls. Nat. Methods 3, 17–21 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S. et al. Flexible ordering of antibody class switch and V(D)J joining during B-cell ontogeny. Genes Dev. 27, 2439–2444 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker K. F. et al. Persistent androgen receptor-mediated transcription in castration-resistant prostate cancer under androgen-deprived conditions. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 10765–10779 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne C. S. et al. Active genes dynamically colocalize to shared sites of ongoing transcription. Nat. Genet. 36, 1065–1071 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuerffel R. et al. S-S synapsis during class switch recombination is promoted by distantly located transcriptional elements and activation-induced deaminase. Immunity 27, 711–722 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowper-Sal lari R. et al. Breast cancer risk-associated SNPs modulate the affinity of chromatin for FOXA1 and alter gene expression. Nat. Genet. 44, 1191–1198 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Kadura I., Fu D. J. & Watson D. E. Genotyping with TaqMAMA. Genomics 83, 311–320 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-5, Supplementary Tables 1-2.

Genes uniquely expressed in G 12878, K562 and HelaS3 cells