Abstract

The mitochondrial contact site and cristae organizing system (MICOS) complex is essential for normal mitochondria biogenesis and morphology. In this issue, Bohnert et al. (2015) and Barbot et al. (2015) demonstrate that a MICOS core subunit, Mic10, is crucial for mitochondrial cristae formation by forming oligomers at the cristae junctions.

The mitochondrial contact site and cristae organizing system (MICOS) complex is essential for normal mitochondria biogenesis and morphology. In this issue, Bohnert et al. (2015) and Barbot et al. (2015) demonstrate that a MICOS core subunit, Mic10, is crucial for mitochondrial cristae formation by forming oligomers at the cristae junctions.

Main Text

It has long been unclear how mitochondrial cristae are formed, and two recent breakthroughs have dramatically changed our view on this topic. First, work from several groups has identified a novel protein complex, MICOS, located at the base of the cristae junctions (Alkhaja et al., 2012; Harner et al., 2011; Hoppins et al., 2011; von der Malsburg et al., 2011). Second, formation of cristae tips has been shown to require the formation of F1Fo-ATPase dimers and oligomers that induce membrane curvature at the cristae tips and play a role in cristae stabilization (Davies et al., 2012; Rabl et al., 2009). In a technical tour de force, two elegant studies in this issue of Cell Metabolism (Barbot et al., 2015; Bohnert et al., 2015) shed additional light on the role of the MICOS complex by showing that oligomerization of one of its core components, Mic10, is essential for formation of cristae junctions.

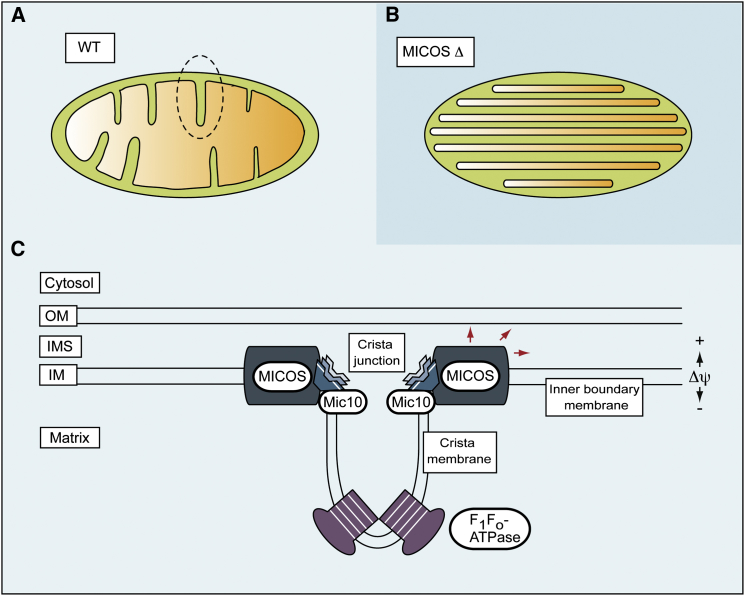

Mitochondria are double-membrane-bound organelles with a complex architecture that is required for their normal metabolic function and that is abnormal in various types of mitochondrial dysfunction (Pfanner et al., 2014). In contrast to the lipid-rich outer mitochondrial membrane that represents a barrier toward the rest of the cell, the inner mitochondrial membrane contains an extremely high protein content and has an enlarged surface area due to its characteristic cristae invaginations (Vogel et al., 2006). Topologically, the inner mitochondrial membrane can be divided into two distinct domains: the inner boundary membrane located in close proximity to the outer mitochondrial membrane and the cristae with lamellar or tubular shapes (Pfanner et al., 2014; Rabl et al., 2009; Vogel et al., 2006) (Figures 1A and 1C). The different domains of the inner mitochondrial membrane have strikingly different protein contents, e.g., the respiratory chain complexes and supercomplexes are highly enriched in cristae membranes, whereas the mitochondrial import and assembly machineries are preferentially found in the inner boundary membrane (Davies et al., 2012; Vogel et al., 2006). Narrow tubular openings termed cristae junctions separate the cristae from the inner boundary membranes and limit the dynamic distribution of proteins (Figure 1C). In addition, cristae junctions partition the metabolite content of the intracristal and the intermembrane spaces, thus influencing the function of the oxidative phosphorylation system (Pfanner et al., 2014). The cristae have also been reported to remodel during apoptosis to facilitate the release of cytochrome c from the intracristal space into the cytosol.

Figure 1.

Mic10 Oligomerization Promotes Cristae Junction Formation

(A) Morphological features of wild-type (WT) mitochondria with characteristic inner-membrane cristae invaginations.

(B) In MICOS mutants (MICOS Δ), the mitochondrial cristae junctions are lost and the inner membrane forms internal membrane stacks.

(C) Schematic representation of inner-membrane complexes determining cristae morphology. The MICOS complex is enriched at cristae junctions and shows multiple interactions with various outer-membrane and inner-membrane proteins (red arrows). Mic10 oligomerization is crucial for membrane bending and the formation of cristae junctions. Dimerization and oligomerization of the F1Fo-ATPase is necessary for the inner-membrane curvature at the cristae tips. Glycine-rich motifs (white stripes) are present in both of the Mic10 transmembrane domains and in subunit c of the Fo-ATP synthase and are thought to drive oligomerization of these proteins. OM, outer mitochondrial membrane; IMS, inter-membrane space; IM, inner mitochondrial membrane.

The MICOS complex is enriched at cristae junctions and consists of at least six proteins (Pfanner et al., 2014). In addition to its role in cristae formation, MICOS also forms contacts with several outer-membrane proteins with roles in mitochondrial protein import and physiology (Pfanner et al., 2014) (Figures 1A–1C). Transient interactions between MICOS and the intermembrane space import receptor Mia40 and cardiolipin (the mitochondrial signature phospholipid) have also been described (von der Malsburg et al., 2011). Yeast studies have revealed strong genetic interactions with the ER-mitochondria encounter structure (ERMES) (Hoppins et al., 2011). These various interactions thus place MICOS in the center of a large organizing network controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and function.

The reports by Barbot et al. (2015) and Bohnert et al. (2015) give mechanistic insights into cristae formation and show that Mic10 plays a central role in forming the inner-membrane curvature at the cristae junctions. Importantly, the two groups base their conclusions on complementary experimental approaches: biochemical in vitro reconstitution assays (Barbot et al., 2015) and molecular characterization of an impressive number of yeast mutants (Bohnert et al., 2015). The fact that the MICOS complex is highly conserved during evolution with five out of the six yeast core subunits having mammalian homologs emphasizes its importance in mitochondrial physiology. Using independent methods, both studies also resolve the previously controversial topology of Mic10 (Alkhaja et al., 2012; Harner et al., 2011; von der Malsburg et al., 2011) and show that this protein has two transmembrane segments that span the inner mitochondrial membrane in a hairpin-like structure so that the short N- and C-terminal ends are located in the intermembrane space. In addition, analysis of characteristic glycine motifs (GxGxGxG) (Alkhaja et al., 2012; Harner et al., 2011) that are found in both of the predicted transmembrane segments of Mic10 show that these residues are important for homo-oligomerization, which in turn facilitates inner-membrane bending and cristae junction formation (Figure 1C). These findings are well in line with previous observations that glycine motifs in transmembrane segments of proteins promote protein-protein interactions and oligomerization in lipid bilayers (Harner et al., 2011). Notably, the glycine rich GxGxGxG motif is also found in the transmembrane segment of subunit c of complex V (F1Fo-ATPase), which homo-oligomerizes to create the Fo ring structure (Figure 1C). Moreover, the GxGxGxG stretch consists of two entwined GxxxG motifs, and such glycine motifs are found in transmembrane domains of the yeast Atp20 and Atp21 subunits that are critical for F1Fo-ATPase dimerization (Alkhaja et al., 2012; Harner et al., 2011). Based on these observations, it is reasonable to assume that interplay between Mic10 oligomerization and F1Fo-ATPase dimerization is necessary to drive cristae formation. It will be exciting to see how the interplay between these multisubunit membrane machineries is coordinated.

Also, other factors, such as different proteolytically processed isoforms of the dynamin-related GTPase Mgm1/Opa1, scaffolding proteins like prohibitins and mitochondrial lipids, have been proposed to play important roles in shaping the inner mitochondrial membrane. However, the involvement of these factors in cristae organization may be indirect, and it is possible that the main effect they have is explained by an altered ratio of proteins to lipids in the inner membrane, which indirectly may lead to an altered inner-membrane organization.

The recent insights into the molecular mechanisms for cristae formation are certainly a major advance in our understanding of mitochondrial ultrastructure. It will be an important goal for the future to understand how the inner-membrane organization impacts oxidative phosphorylation and how cristae can be remodeled to promote apoptosis.

Acknowledgments

N.-G.L. is supported by a European Research Council advanced investigator grant (268897) and by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB829).

Footnotes

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Contributor Information

Dusanka Milenkovic, Email: dusanka.milenkovic@age.mpg.de.

Nils-Göran Larsson, Email: larsson@age.mpg.de.

References

- Alkhaja A.K., Jans D.C., Nikolov M., Vukotic M., Lytovchenko O., Ludewig F., Schliebs W., Riedel D., Urlaub H., Jakobs S., Deckers M. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2012;23:247–257. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-09-0774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbot M., Jans D.C., Schulz C., Denkert N., Kroppen B., Hoppert M., Jakobs S., Meinecke M. Cell Metab. 2015;21:756–763. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.04.006. this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert M., Zerbes R.M., Davies K.M., Mühleip A.W., Rampelt H., Horvath S.E., Boenke T., Kram A., Perschil I., Veenhuis M. Cell Metab. 2015;21:747–755. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.04.007. this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies K.M., Anselmi C., Wittig I., Faraldo-Gómez J.D., Kühlbrandt W. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:13602–13607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204593109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harner M., Körner C., Walther D., Mokranjac D., Kaesmacher J., Welsch U., Griffith J., Mann M., Reggiori F., Neupert W. EMBO J. 2011;30:4356–4370. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppins S., Collins S.R., Cassidy-Stone A., Hummel E., Devay R.M., Lackner L.L., Westermann B., Schuldiner M., Weissman J.S., Nunnari J. J. Cell Biol. 2011;195:323–340. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201107053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfanner N., van der Laan M., Amati P., Capaldi R.A., Caudy A.A., Chacinska A., Darshi M., Deckers M., Hoppins S., Icho T. J. Cell Biol. 2014;204:1083–1086. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201401006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabl R., Soubannier V., Scholz R., Vogel F., Mendl N., Vasiljev-Neumeyer A., Körner C., Jagasia R., Keil T., Baumeister W. J. Cell Biol. 2009;185:1047–1063. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200811099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel F., Bornhövd C., Neupert W., Reichert A.S. J. Cell Biol. 2006;175:237–247. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200605138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von der Malsburg K., Müller J.M., Bohnert M., Oeljeklaus S., Kwiatkowska P., Becker T., Loniewska-Lwowska A., Wiese S., Rao S., Milenkovic D. Dev. Cell. 2011;21:694–707. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]