Abstract

Associations of maternal self-report anxiety-related symptoms with mother–infant 4-month face-to-face play were investigated in 119 pairs. Attention, affect, spatial orientation, and touch were coded from split-screen videotape on a 1-s time base. Self- and interactive contingency were assessed by time-series methods. Because anxiety symptoms signal emotional dysregulation, we expected to find atypical patterns of mother–infant interactive contingencies, and of degree of stability/lability within an individual’s own rhythms of behavior (self-contingencies). Consistent with our optimum midrange model, maternal anxiety-related symptoms biased the interaction toward interactive contingencies that were both heightened (vigilant) in some modalities and lowered (withdrawn) in others; both may be efforts to adapt to stress. Infant self-contingency was lowered (“destabilized”) with maternal anxiety symptoms; however, maternal self-contingency was both lowered in some modalities and heightened (overly stable) in others. Interactive contingency patterns were characterized by intermodal discrepancies, confusing forms of communication. For example, mothers vigilantly monitored infants visually, but withdrew from contingently coordinating with infants emotionally, as if mothers were “looking through” them. This picture fits descriptions of mothers with anxiety symptoms as overaroused/fearful, leading to vigilance, but dealing with their fear through emotional distancing. Infants heightened facial affect coordination (vigilance), but dampened vocal affect coordination (withdrawal), with mother’s face—a pattern of conflict. The maternal and infant patterns together generated a mutual ambivalence.

Face-to-face play elicits the infant’s most advanced communication capacities, and its developmental importance is widely recognized (Field, 1995; Jaffe, Beebe, Feldstein, Crown, & Jasnow, 2001; Lewis & Feiring, 1989; Malatesta, Culver, Tesman, & Shepard, 1989; Tronick 1989). The negative effects of postnatal maternal depressive symptoms on mother– infant communication and child development have been extensively documented (Cohn, Campbell, Matias, & Hopkins, 1990; Field, 1995; Murray, Fiori-Cowley, Hooper, & Cooper, 1996; Tronick, 1989). But little work has investigated the effects of maternal anxiety-related symptoms on mother–infant face-to-face play in early infancy, the subject of this report.

Whereas attention to the effects of prenatal maternal anxiety symptoms has increased (O’Connor, Heron, Golding, Beveridge & Glover, 2002), the effects of postnatal maternal anxiety symptoms in early infancy remain less examined (Kaitz & Maytal, 2005; Matthey, Barnett, Howie, & Kavanagh, 2003; Miller, Pallant, & Negri, 2006). Britton (2005) noted that even moderate postpartum maternal anxiety is associated with adverse parenting. Anxious mothers evidence diminished feelings of efficacy in the parenting role (Gondoli & Silverber,1997; Porter & Hsu, 2003), reduced coping capacity (Barnett & Parker, 1986), decreased behavioral competence (Teti & Gelfand, 1991), reduced positive emotional tone (Nicol-Harper, Harvey, & Stein, 2007), less warmth and more criticism (Weinberg & Tronick, 1998), more intrusion (Feldman, 2007; Weinberg & Tronick, 1998, Wijnroks, 1999), and less active engagement (Murray, Cooper, Creswell, Schofield, & Sack, 2007). Infants of anxious mothers cry more (Papousek & von Hofacker, 1998). Mothers with comorbid depression and anxiety symptoms (vs. depressed mothers) are less positive (less smiling, less exaggerated facial expressiveness, less game-playing and imitating); their infants spend less time smiling and more time in distressed brow and crying (Field et al., 2005).

Weinberg and Tronick (1998) reported that psychiatrically ill mothers (panic disorder, major depressive disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder) versus controls are more disengaged with their infants in face-to-face play (less vocalizing, fewer interest expressions, less touch, and less shared focus of attention on objects). During the reunion episode of the still-face paradigm with mother, as well as during an interaction with strangers, proband infants were more negative (less interest, more anger and sadness, more fuss/cry), indicating more difficulty repairing the interaction after the disruption. The strangers were more disengaged (less touching, greater physical distance) when interacting with proband infants.

Reduced maternal sensitivity has been associated with maternal anxiety symptoms in some studies (Feldman, Greenbaum, Mayes, & Erlich, 1997; Nicol-Harper et al., 2007; Warren et al., 2003), especially when infants have high negative affect (Mertesacker, Bade, Haverkock, & Pauli-Pott, 2004). But other studies have failed to find reduced maternal sensitivity (Kaitz, Maytal, Devor, Bergman, & Mankuta, 2010; Murray et al., 2007). Feldman (2007) found increased maternal intrusion and lower infant social involvement in more anxious mothers during 4-month face-to-face interaction. Weinberg, Beeghly, Olson, and Tronick (2008) failed to find any differences in anxious mothers or their infants at 6 months. Kaitz et al. (2010) found that anxious mothers showed more exaggerated behaviors and that their infants showed less negative affect in the still-face and reunion episodes of the still-face paradigm; but otherwise, there were no maternal or infant differences despite detailed microanalytic video coding and extensive testing. Warren et al. (2003) found no differences during face-to-face communication in infants of panic disorder mothers, but did document increased infant cortisol levels. Murray et al. (2007) found no behavioral differences in infants of socially phobic mothers at 10 weeks, but infants were less responsive to a stranger.

Whereas many of these studies have highlighted the importance of maternal anxiety symptoms for child development, there is still relatively little detailed description of the effects of maternal anxiety symptoms on early mother–infant face-to-face communication. Where studies have begun to analyze communication in detail, results have been absent, scarce, or contradictory. Thus, more detailed description is needed to understand the nature of communication disturbances that may be associated with maternal anxiety-related symptoms.

A DYADIC SYSTEMS VIEW OF COMMUNICATION

A dyadic systems view of face-to-face communication informs our research (Beebe & Lachmann, 2002; Jaffe et al., 2001). Because each person must monitor and coordinate with the partner, as well as regulate inner state, in this view all interactions are a simultaneous product of self-and interactive processes (Gianino & Tronick, 1988; Sander, 1977; Thomas & Martin, 1976; Tronick, 1989). Fogel (1993) described all behavior as unfolding in the individual while also modifying and being modified by the changing behavior of the partner. Although rarely studied together, both self- and interactive processes are essential to communication. Both intrapersonal and interpersonal behavioral rhythms provide the ongoing temporal information necessary to predict and coordinate with one’s partner, so that each can anticipate how the other will proceed (Feldman, 2006; Warner, 1992).1

We study self- and interactive processes with measures of “contingency,” a term we use interchangeably with “predictability” and “coordination.” Contingencies are defined as predictability of behavior over time, analyzed by time-series techniques. Interactive contingency picks up consistently occurring, moment-to-moment adjustments that each individual makes to changes in partner behavior. It is defined as the predictability of each partner’s behavior from that of the other, over time (lagged cross-correlation), translated into the metaphor of expectancies of “how I affect you,” and “how you affect me.” Self-contingency (auto-correlation) indexes the degree to which any prior state predicts the next observed state, and is considered one form of self-regulatory process (Thomas & Malone, 1976; Warner, 1992). It is interpreted as the stability/lability of each person’s own behavior over time, in the presence of a particular partner.

Contingency processes are the foundation of social communication. Contingency in social behavior reduces uncertainty about what is likely to happen next (Warner, 1992). By 4 months, infants are adept at perceiving contingent relations, as well as discriminating degrees thereof, and generating expectancies (predictions) based upon them (DeCasper & Carstens, 1980; Haith, Hazan, & Goodman, 1988; Watson, 1985). They are highly sensitive to the ways in which their behaviors are contingently responded to (DeCasper & Carstens, 1980; Hains & Muir, 1996; Haith et al., 1988; Murray & Trevarthen, 1985; Tarablusy, Tessier, & Kappas, 1996; Watson, 1985). The nature of each partner’s contingent coordination with the other, termed “mutual regulation” by Tronick (1989), affects the infant’s ability to attend, process information, and modulate behavior and emotional state (Hay, 1997). Contingency processes are essential to the creation of infant and maternal social expectancies and interactive efficacy, and infant cognitive and social development (Feldman, 2007; Hay, 1997; Lewis & Goldberg, 1969; Murray & Cooper, 1997; Trevarthen, 1977; Tronick, 1989).

THE MEANING OF HIGHER AND LOWER DEGREES OF SELF- AND INTERACTIVE CONTINGENCY

Contradictory theories of the meaning of interactive contingency have proposed that (a) high coordination is optimal for communication (Chapple, 1970), (b) high coordination indexes communicative distress (Gottman, 1979), or (c) our position (Beebe et al., 2007; Beebe et al., 2008a; Jaffe et al., 2001), an optimal midrange model in which both excessive and insufficient coordination index social distress (see Cohn & Elmore, 1988; Kaitz & Maytal, 2005; Warner, Malloy, Schneider, Knoth, & Wiler, 1987). Social experiences that force the infant to pay too much or too little attention to the partner may disturb the infant’s ability to modulate his or her emotional state while processing information, and are likely to disturb social and cognitive development (Hay, 1997).

Our previous work has documented that high or low poles of interactive contingency during mother–infant face-to-face play predicted attachment insecurity (Beebe et al., 2010; Jaffe et al., 2001; Markese, Beebe, Jaffe, & Feldstein, 2008), maternal depression (Beebe et al., 2008a), and maternal self-criticism and dependency (Beebe et al., 2007). Other research has converged on such a model, in which distress biases the system toward both heightened interactive contingency (in some modalities) and lowered (in others) (Belsky, Rovine, & Taylor, 1984; Hane, Feldstein, & Dernetz, 2003; Leyendecker, Lamb, Fracasso, Scholmerich, & Larson, 1997; Lewis & Feiring, 1989; Malatesta et al., 1989; Roe, Roe, Drivas, & Bronstein, 1990).

We interpret heightened interactive contingency as an effort to create more predictability in contexts of novelty, challenge, or threat, translated into “activation” or “vigilance.” Vigilance for social signals is an important aspect of social intelligence, likely an evolutionary advantage with uncertainty or threat (Ohman, 2002). Clinically, this picture might translate into a mother who is “trying too hard” or “following too closely.” We interpret low coordination as “inhibition” or “withdrawal,” where metaphorically each partner is relatively “alone” in the presence of the other (Beebe et al., 2000; Jaffe et al., 2001). The partner’s lowered interactive contingency compromises the individual’s ability to anticipate consequences of his or her own actions for the partner, lowering interactive agency. Mothers and infants heighten and/or lower their self-and interactive contingencies not out of conscious intention but based on procedurally organized action sequences. Our use of the term procedural includes a view of the infant as an active agent in the construction of procedural knowledge.

Self-contingency has seen little study. Whereas other researchers have either ignored self-contingency (e.g., Stern, 1971) or removed it statistically (Cohn & Tronick, 1988; Jaffe et al., 2001), we treat it as a variable in its own right (see Badalamenti & Langs, 1990; Crown et al., 1996; Thomas & Malone, 1979; Warner, 1992). When one’s ongoing behavioral stream is less predictable, we infer lowered ability to anticipate one’s next move, a “destabilization.” In contrast, heightened self-contingency indicates behavior tending toward an overly steady, nonvarying process, translated into the metaphor of “self-stabilization.”

In examining vocal rhythms in adult conversations of unacquainted pairs, Warner (1992) found lowered self-contingency associated with lowered contingent coordination with the partner’s behavior, and with a less positive evaluation of the conversation. Our prior work has shown primarily lowered self-contingency associated with maternal depression and self-criticism. However, we found heightened as well as lowered infant self-contingency associated with infant disorganized attachment, and heightened infant self-contingency in the context of the novel stranger (Beebe et al., 2007; Beebe et al., 2008a; Beebe et al., 2010; Beebe et al., 2009). Thus, both poles of heightened and lowered self-contingency may be problematic.

COMMUNICATION MODALITIES

Face-to-face communication generates multiple simultaneous emotional signals which, although typically congruent, may be discordant in the context of disturbance (Shackman & Pollak, 2005). Using detailed video microanalysis, we investigate whether specific modalities of the face-to-face exchange (attention, affect, touch, and spatial orientation) differ in patterns of self- and interactive contingency, defining different aspects of disturbance. Building on our prior findings examining maternal depression (Beebe et al., 2008a) and infant disorganized attachment (Beebe et al., 2010), we hypothesize that distress in either partner may be associated with intermodal discordances, generating confusing communication patterns. Only examination of separate modalities can identify such discordances (also see Bahrick, Hernandez-Reif, & Flom, 2005; Keller, Lohaus, Volker, Cappenberg, & Chasiotis, 1999; Van Egeren, Barratt, & Roach, 2001; Weinberg & Tronick, 1994; Yale, Messinger, Cobo-Lewis, & Delgado, 2003). For example, in our prior work, depressed (vs. control) mothers showed lowered gaze, but heightened facial, contingent coordination with their infants (Beebe et al., 2008a).

Using separate modalities, we analyze visual attention (gaze), affect (facial and vocal), touch, and orientation. Gaze, facial affect, and vocalization have been well studied, and mothers are contingently responsive to infants in these modalities (Bigelow, 1998; Cohn & Tronick, 1988; Keller et al., 1999; Van Egeren et al., 2001). Infants are sensitive to variations in the form, intensity, and timing of adult gaze and facial and vocal behavior, and are capable of coordinating with them to apprehend attentional and affective states (Gusella, Muir, & Tronick, 1988; Jaffe et al., 2001; Messinger, 2002; Muir & Hains, 1993; Murray & Cooper, 1997; Stern, 1985; Trevarthen, 1977; Tronick, 1989).

Infant touch is important for infant self-soothing (Tronick, 1989; Weinberg & Tronick, 1994). In studies of face-to-face interaction, infants use more self-touch (a) during the still-face experiment (Weinberg & Tronick, 1996), (b) when mother leaves the room or a stranger enters (Trevarthen, 1977), (c) when infants view a noncontingent “replay” of the mother’s behavior (Murray & Trevarthen, 1985), or (d) when infants will be classified Avoidant Attachment at 12 months (Koulomzin et al., 2002).

Affectionate to intrusive patterns of maternal touch are a central, but less examined, modality (Feldman, 2007; Field, 1995; Moreno, Posada, & Goldyn, 2006; Stepakoff, Beebe, & Jaffe, 2000; Stack, 2001). Van Egeren et al. (2001) documented bidirectional contingency between mother touch and infant vocalization. Maternal touch can compensate when facial or vocal communication is not available, as in the still-face experiment (Pelaez-Nogueras, Field, Hossain, & Pickens, 1996; Stack & Arnold, 1998; Stack & Muir, 1992). For example, self-critical mothers showed difficulty joining the infant’s direction of gaze and difficulty entering the infant’s emotional ups and downs, but compensated by becoming overly involved with touch, a more concrete modality than face or gaze (Beebe et al., 2007).

Maternal spatial orientation (sitting upright, leaning forward, looming in) and infant head orientation (from enface to arch) organize approach–avoid patterns which are central means of regulating proximity (Beebe & Stern, 1977; Demetriades, 2003; Kushnick, 2002; Stern, 1971; Tronick, 1989). We did not analyze maternal vocal behavior. [Our automated vocal rhythm measure (Jaffe et al., 2001) will be used in a separate report.]

APPROACH OF THE STUDY

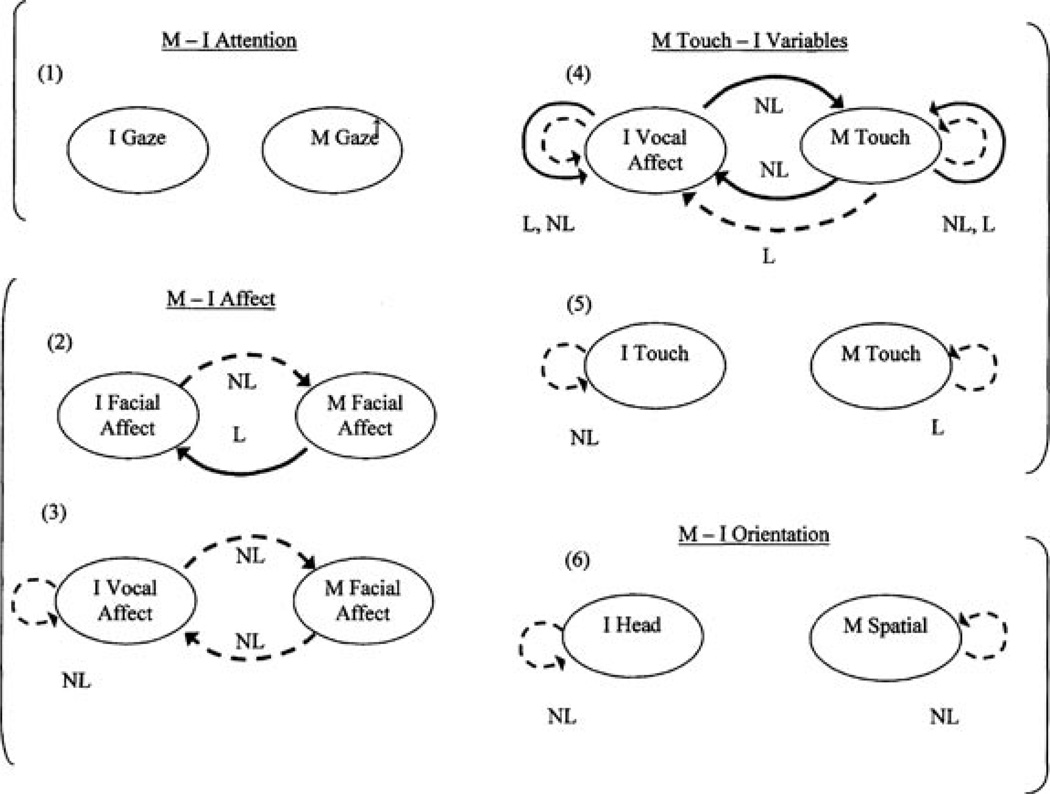

We generated six mother–infant “modality pairings,” attempting to examine the same modality in both partners where possible (Pairings 1, 2, 5, and 6):

infant gaze–mother gaze

infant facial affect–mother facial affect

infant vocal affect–mother facial affect

infant vocal affect–mother touch

infant touch–mother touch

infant head orientation–mother spatial orientation.

These six modality pairings address the four domains of visual attention (Pairing 1), affect (Pairings 2 & 3), maternal touch (Pairings 4 & 5), and spatial orientation (Pairing 6). We examine infant vocal affect as a second way of exploring infant emotional response to maternal facial affect (Hsu & Fogel, 2003). We examine maternal touch in relation to infant vocal affect and touch, reasoning that infants may respond to intrusive touch with vocal distress or increased touch (see Van Egeren et al., 2001).

The specificity of this approach allows us to “unpack” interactions which might be coded as interactive errors (Tronick, 1989) or communication errors (Lyons-Ruth, Bronfman, & Parsons, 1999). It identifies intermodal discrepancies, which may be intrapersonal or dyadic. Thus, this approach allows us to more clearly understand what the infant’s experience might be. For example, we may identify difficulties in the regulation of attention, separate from the regulation of affect. Interactive contingency of gaze examines the degree to which each partner follows the direction of the other’s visual attention, on and off the partner’s face. Interactive contingency of affect was examined as two patterns of affective “mirroring,” the degree to which partners share direction of affective change: (a) facial affect mirroring and (b) cross-modal maternal facial affect–infant vocal affect mirroring. The coordination of infant touch and maternal touch examines the degree to which, as infants touch more, mothers touch more affectionately (and vice versa) and whether the relative affectionate quality of maternal touch affects infant likelihood of touch (and vice versa). In this context, we can examine whether maternal touch might be a compensatory modality when attention or affect is problematic. Maternal contingent spatial coordination with infant head orientation measures mutual approach and withdrawal patterns (mother’s likelihood of leaning forward or looming in as the infant reorients toward enface; and reciprocally, mother’s likelihood of sitting back in an upright posture as the infant orients away). Infant head-orientation coordination with maternal spatial orientation measures the infant’s likelihood of being involved in a maternal approach—infant withdrawal pattern (infant’s likelihood of arching away as mother looms in Beebe & Stern’s, 1977, “chase and dodge” pattern, and reciprocally, the infant’s likelihood of reorienting as mother sits back).

In this article, we investigate associations of maternal self-reported anxiety-related symptoms with mother–infant self- and interactive contingencies in the six modality pairings listed earlier. As a function of higher (vs. lower) maternal anxiety symptoms, we investigate (a) which partner (mother/infant) shows altered 4-month contingency, (b) the type of contingency (self/interactive) that is altered, (c) whether contingency is increased or decreased, and (d) the modality of contingency that is altered. We also explore whether maternal anxiety symptoms are associated with differences in qualitative features of behavior (e.g., intrusive maternal touch).

We examine the effects of maternal anxiety symptoms irrespective of depressive-symptom status, following most previous studies, reflecting the high prevalence of comorbid anxious and depressive states (Austin, 2004; Heron, O’Connor, Evans, Golding, & Glover, 2004; Kaufman & Charney, 2000; Matthey et al., 2003; Miller et al., 2006). The anxiety symptoms of the assessment method we used, the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Spielberger, Gorsuch, & Lushene, 1983), are not specific to anxiety or depression but they do reflect internal discomfort and likely heightened stress. Some researchers hold that the STAI indexes general distress and negative affectivity more so than anxiety specifically (Nitschke, Heller, Imig, McDonald, & Miller, 2001; Pizzagalli et al., 2002). Thus, we do not address anxiety disorder, but a more general distress.

HYPOTHESES

Building on our documentation of an “optimal midrange” model of interactive contingency (Jaffe et al., 2001), in which both heightened and lowered degrees of vocal rhythm contingency predicted different categories of insecure attachment, we hypothesize that maternal anxiety symptoms bias mother–infant communication toward both heightened interactive contingency (in some modalities) and lowered (in others). Because we analyze each modality separately, heightened (or lowered) contingency with maternal anxiety will be evident in different modalities. For example, we previously documented that in dyads where mothers had higher depressive symptoms, mothers and infants had both higher contingencies (in affect) and lower contingencies (in gaze) than did dyads with lower maternal symptoms (Beebe et al., 2008a). Such findings are conceptually midrange, or consistent with our optimal midrange model, rather than statistically nonlinear. Similarly, because our prior work noted earlier has identified both heightened and lowered self-contingency in contexts such as maternal distress, infant attachment insecurity, and the challenge of the novel stranger, we anticipate that in the context of maternal anxiety symptoms, we will find both heightened and lowered self-contingencies of both partners.

Building on our prior findings examining maternal depression and self-criticism, and infant disorganized attachment (Beebe et al., 2007; Beebe et al., 2008a; Beebe et al., 2010), we hypothesize that distress in either partner may be associated with intermodal discordances, generating confusing communication patterns.

In the absence of much literature, we hypothesize about heightened and/or lowered interactive contingencies in specific modalities. Building on Kaitz and Maytal’s (2005) view that anxious mothers may be “underresponsive” (i.e., withdrawn, self-absorbed), dealing with their own fear and overarousal by emotional distancing, we anticipate that anxious mothers will show lowered interactive contingencies in affective modalities. Based on the suggestion that anxious mothers also may be “overreactive,” and the concept that anxious mothers may be vigilant in response to their own fearfulness and overaroused inner state (Barlow, 1991; Kaitz & Maytal, 2005), looking to see what will happen, we anticipate that these mothers will show heightened interactive contingencies in gaze. If there are difficulties in the regulation of affect or visual attention, as we expect, we anticipate mothers will compensate with heightened interactive contingency of touch (see Beebe et al., 2007; Pelaez-Nogueras et al., 1996; Stack & Muir, 1992).

We anticipate that infants will show heightened contingent coordination with their mothers in some modalities, in an effort to process aspects of the mother’s disturbed communication. Following de Rosnay, Cooper, Tsigaras, and Murray (2006), we anticipate that infants will be overly sensitive to maternal affective communications, showing heightened interactive contingencies in affective modalities. We also anticipate that infants will show lowered contingency with mothers in the other modalities, consistent with a description of infants of anxious mothers as withdrawn, or avoidant (Feldman, 2007; Kaitz & Maytal, 2005). If these hypotheses are verified, combinations of both heightened and lowered interactive contingencies may yield intermodal discordances, generating confusing communication patterns, as proposed earlier.

In addition to process measures of contingency over time, we also used content measures of qualitative features of behavior. We hypothesize that maternal anxiety symptoms are associated with maternal intrusive touch and negative facial affect, and negative infant vocal affect reflecting distress/ irritability (de Rosnay et al., 2006; Feldman, 2007; Kaitz & Maytal, 2005; Papousek & von Hofacker, 1998; Weinberg & Tronick, 1998).

THE PROBLEM OF LOW SCORES IN SELF-REPORT SCALES

Self-report scales constitute the central measurement of maternal distress in child development research. Such scales are vulnerable to “denial” of distress (Shedler, Mayman, & Manis, 1993), so that low scores may be difficult to interpret. Using coronary reactivity, Schedler, Mayman, and Manis (1993) showed that some subjects with low self-report depression had lower coronary reactivity; but for subjects clinically judged “distressed,” lower depression scores were correlated with higher coronary reactivity. Debate exists as to whether low-scoring mothers might be “denying” their distress. Pickens and Field (1993) showed that infants of low-scoring mothers (Beck Depression Inventory) had more negative facial expressions, whereas Tronick, Beeghly, Weinberg, and Olson (1997) argued that low scores on The Center for Epidemiological Studies Repression Scale (the CES-D) represented “postpartum exuberance.” Lyons-Ruth, Zoll, Connell, and Grunebaum (1986) found that mothers who scored zero on the CES-D were high on covert hostility and interference during mother–infant interaction. Blank (1986) found that very low anxiety symptom scores (but not high) were associated with feeding difficulties and altered cortisol levels. Some mothers at the low end may indeed be distress-free whereas others may deny distress. Shedler et al. (1993) solved this problem with an independent measure of distress.

Consistent with Shedler et al. (1993), our prior work on maternal distress (depression, self-criticism, and dependency; Beebe et al., 2007; Beebe et al., 2008a) showed that altered self- and interactive contingency patterns were similar at both high and low poles of distress (compared to dyads with mothers scoring midrange in distress), suggesting that both poles of scores may be problematic. We reasoned that some mothers volunteering for a study of infant social development may be motivated to “downplay,” and possibly “deny,” distress. Building on our prior work, in this study we hypothesize that high and low poles of maternal anxiety also will show similar patterns of altered contingencies. We explore low scores using nonlinear analyses of anxiety symptoms in relation to contingency. If our hypothesis is confirmed, report of very low symptoms may be problematic; however, we remain cautious: Without an independent distress measure, some participants at the low pole may be distress-free.

Earlier, we hypothesized an “optimum midrange” model of contingency: Both low as well as high contingencies, in different communication modalities, may be associated with higher anxiety. Here, our examination of low as well as high anxiety scores constitutes another type of “optimum midrange” model of anxiety: Low as well as high poles of self-report anxiety may have similar altered contingencies, compared to mothers scoring midrange in anxiety. The former is a “conceptual” midrange model of contingency whereas the latter is a statistically nonlinear approach to anxiety.

METHOD

Participants

Recruitment

Within 24 hr of delivering a healthy, full-term singleton infant without major complications, 152 primiparous mothers were recruited from an urban university hospital for a study of infant social development involving a 4-month lab visit. Participants were 18 years or older, married or living with a partner, with a home telephone. Mothers meeting criteria were consecutively approached. At 6 weeks, mothers were invited to participate by telephone. At 4 months, 119 mothers came to the lab, were videotaped with their infants, and then filled out anxiety-symptom scales. No mothers were in treatment or medicated. There were no differences in ethnicity, education, or infant gender between the 119 participants and the 152 recruited.

Demographic Description

Mothers were 53.0% White, 28.0% Hispanic, 17.5% Black, 1.5% Asian; well-educated (3.8% without high-school diploma, 8.3% without college, 28.8% some college, 59.1% college+); mean age was 29 (SD = 6.5, range = 18–45) years. Of 119 infants, 65 were male, and 54 were female.

Procedure

Scheduling of videotaping took into account infants’ schedules. Mothers (seated opposite infants who were seated on a table) were instructed to play with their infants as they would at home, but without toys, for approximately 10 min (necessary to obtain vocal rhythm data for a separate report). A special-effects generator created a split-screen view from input of two synchronized cameras focused on mother and infant.

Measurement of anxiety symptoms

The STAI (Spielberger et al., 1983), a 40-item self-report scale, has items such as “nervous,” “jittery,” “high strung,” “rattled,” and “overexcited.” State-Anxiety (SAS) evaluates how respondents feel “right now, at this moment.” Trait-Anxiety (SAT) evaluates how participants “generally feel” with an identical set of items. SAS and SAT have been shown to be highly correlated. Test-retest coefficients for SAT range from .73 to .86 for college students, but are lower for SAS, as expected. Both forms have high internal consistency (α coefficients: SAS = .87, SAT = .90). We chose SAT, rather than SAS, to evaluate how mothers characterize themselves in general. Because SAT and the CES-D were correlated (r = .65), a subsequent report will analyze both scales in the same analyses. Here, we report on SAT alone, more comparable to the literature. SAT was treated as a continuous variable in all data analyses.

Behavioral coding

The first uninterrupted, continuous-play minutes of videotaped mother– infant play were coded on a 1-s time base (see Cohn & Tronick, 1988; Field, Healy, Goldstein, & Guthertz, 1990) by coders blind to anxiety status, using Tronick and Weinberg’s (1990) timing rules. Codes were used to create ordinalized behavioral scales for data analysis (required by time-series techniques). Definitions of behavioral scales follow. Gaze: on-off partner’s face; mother facial affect: mock surprise, smile 3, smile 2, smile 1, “oh” face, positive attention, neutral, “woe” face, negative face (frown, grimace, compressed lips); infant facial affect: high positive, low positive, interest/neutral, mild negative (frown, grimace), negative (pre-cry, cry-face); infant vocal affect: positive/neutral, none, fuss/whimper, angry protest/cry; mother spatial orientation: upright, forward, loom; infant head orientation: en face, en face + head down, 30-to 60-degree avert, 30- to 60-degree avert + head down, 60- to 90-degree avert, arch; mother touch: affectionate, static, playful, none, caregiving, jiggle/bounce, oral, object-mediated, into the center of the body, rough, intrusive; infant touch: none, 1, or 2+ of the following behaviors within 1s: touch/suck own skin, touch mother, touch object (Hentel, Beebe, & Jaffe, 2000). A dyadic code, chase and dodge, was defined as a minimum 2-s sequence in which infant averts head 30 degrees or more from vis-à-vis and mother moves her head or body in the direction of the infant’s movement (Kushnick, 2002). We also constructed composite facial– visual “engagement” scales for mother and infant. Please refer to our Web site Appendices A, B, and C for further coding details (http://nyspi.org/Communication_Sciences/index.html).

Doctoral students in psychology independently coded mothers and infants. Reliability estimates (Cohen’s κ) were computed on a per-dyad basis, for 30 randomly selected dyads (tested in three waves to prevent coder “drift”), for ordinalized scales (except mother touch, where κs were computed for the separate behaviors). Mean κs are presented for the 30 dyads (infants: gaze .80, face .78, touch .75, vocal affect .89, head orientation .71; mothers: gaze .83, face .68, touch .90; spatial orientation .89; dyadic chase and dodge .89).

Data Analysis

Analyses of qualitative features of behavior

We first explored associations of maternal anxiety symptoms with qualitative features of behavior, tested as means of the ordinalized behavioral scales, as well as rates of specific “behavioral extremes.” Although main effects of multilevel models could be interpreted for associations with means of behavioral scales, we chose to separately test for effects, without having controlled for the various other variables in our models, more comparable to the literature. For 4-month qualitative features of behaviors (scale means and rates of behavioral extremes), we used correlations and independent-samples t tests.

Because the means of the behavioral scales have yielded little in our previous work, we moved to an exploration of “behavioral extremes” (see Beebe et al., 2010; Lyons-Ruth et al., 1999; Tomlinson, Cooper, & Murray, 2005). For example, the mean of the ordinalized maternal touch scale includes the full range of maternal touch behaviors coded whereas the behavioral extreme of the low end of this scale, intrusive touch, identifies a specific, clinically meaningful behavior. The precise definitions of behaviors in question were critical in our previous work. In our behavioral extremes approach, we investigate whether associations with anxiety symptoms can be found in (a) the mere existence of a particular clinically relevant behavior (i.e., maternal intrusive touch), (b) the mean percentage of time per individual that it was used, or (c) its excessive use (≥20% time). Analyses were tailored to each behavior, as appropriate to the distributions (i.e., many were skewed).

Self- and interactive contingency

The second goal was to investigate associations of maternal anxiety symptoms with self- and interactive contingency. Modeling the complexity of real-time interactions remains difficult. Whereas traditional time-series approaches are considered state-of-the-art, the multilevel time-series models used in this study have many advantages.2 The SAS PROC MIXED program (Littell, Milliken, Stoup, & Wolfinger, 1996; McArdle & Bell, 2000; Singer, 1998) was used to estimate “random” (individual differences) and “fixed” (common model) effects on the pattern of self- and self-with-other behavior over 150 s.3 The models examined six modality pairings, including one (on/off gaze) in which the dependent variable is dichotomous and therefore analyzed by SAS GLIMMIX (Cohen, Chen, Hamgiami, Gordon, & McArdle, 2000; Goldstein, Healy, & Rasbash, 1994; Littell et al., 1996; for details of statistical models, see Chen & Cohen, 2006). These analyses use all 150 s coded from videotape for each individual. In these models, repeated observations on individuals are the basic random data, just as single individual variables are the basic units of analyses in cross-sectional data. Fixed effects, in contrast, indicate average effects over the full sample, so that it is possible to estimate the extent to which a single overall model accounts for the individual differences reflected in the random model.

Preliminary analyses estimated the number of seconds over which lagged effects were significant and their magnitude across the group (fixed model estimates). For each dependent variable, measures of prior self- or partner behavior, “lagged variables,” were computed as a weighted average of the recent prior second. Typically, the prior 3 s sufficed to account for these lagged effects on the subsequent behavior.4 The estimated coefficient for the effects of these lagged variables on current behavior over the subsequent 147 s of interaction indicates the level of self- or interactive contingency: the larger the coefficient, the stronger the contingency. Each subsequent analysis included both self- and interactive contingency; thus, estimated coefficients of one form of contingency control for the other.

Tests of hypotheses use fixed rather than random effects. In preparation for tests of anxiety symptoms (SAT), a “basic model” of fixed (average) effects was produced for each behavioral dependent variable. The modeling process for predicting the time-varying ordinalized behavioral scale in question (e.g., mother facial affect) considered all demographic variables (maternal ethnicity, education, and age; infant gender), effects of lagged variables as described earlier, and all possible two-way interactions between control variables and self- and interactive contingency. Effects of lagged variables on current behavior represent the average contingency across the participants. Therefore, when testing for effects of SAT, any differences in the magnitude of these estimated coefficients in the fixed effects model reflect influences of SAT on self- and interactive contingency. Because our goal was an examination of the effects of SAT on contingency, we post on our Web site (http://nyspi.org/Communication_Sciences/index.html) Appendix D, the “basic model” tables of self- and interactive contingency (three for each of the six modality pairings, for a total of 18 tables). Prior basic across-group analyses (Beebe et al., 2008b) showed positive signs for self-contingency, and for interactive contingency with the exception of Pairing 6: mother spatial orientation-infant head orientation (mother negative sign, infant positive sign).

Variables in the “basic” multilevel model were added in these steps following the intercept of the dependent variable: (1) self- and partner lagged variables, (2) demographic variables, (3) conditional effects between demographic variables, (4) conditional effects of demographic variables with lagged self- and lagged partner behavior. Following each basic model, a conditional model examined the effect of SAT on each ordinalized behavioral scale and statistical interactions of SAT with self- and interactive contingency.5 Linear and quadratic conditional effects of SAT on self- and interactive contingency were assessed in the same models; linear and quadratic components each controlled for the other. Only those demographic variables from the basic models that also were associated with SAT could possibly confound these effects. Because none were associated with SAT, all demographic variables were dropped from further consideration. Each model included a chi-square test of improvement of fit to the data. SAT was used as a continuous variable, centered by its mean. Standardized regression coefficients are presented in the tables. Type I error was set at p < .05 for each model of the six modality pairings; all tests were two-tailed. With 119 dyads × 150 s = 17,850 s per partner per communication modality, we had ample power to detect effects.

Linear components evaluated the conditional effects of higher (vs. lower) SAT scores on self- and interactive contingency; results were interpreted as characterizing higher SAT scores. Nonlinear components evaluated quadratic conditional effects of SAT; results were interpreted as characterizing movement toward the high and low poles, compared to dyads where mothers scored midrange in SAT. Where nonlinear analyses were significant, movement toward both high and low poles of SAT scores were associated with similar alternations in self- and interactive contingency (similar in direction, but not necessarily absolute amount).

Our interpretations occurred in two phases. Consistent with prior literature, we first evaluated findings associated with higher SAT scores. Here, we interpreted the linear as well as the higher portion of the nonlinear effects of SAT (right-hand side of graphed effects) on self- and interactive contingency. In the second phase, we examined nonlinear findings to evaluate whether movement away from the center toward high and low poles of SAT scores was associated with similar increases (or decreases) in self- and interactive contingency.

RESULTS

We first present descriptive information on Spielberger Trait Anxiety (SAT), followed by univariate tests of associations of SAT with ordinalized behavioral scales (facial affect, etc.). Effects of SAT on contingencies are then addressed. Consistent with the literature, we first present contingency findings associated with higher anxiety symptoms, whether linear or nonlinear. We then return to nonlinear equations to evaluate whether contingency findings of low-scoring SAT dyads look similar to those of high-scoring dyads.

Description of Trait Anxiety Symptoms (SAT)

The range of SAT scores at 4 months was 20 to 60 (possible 20–80). Mean SAT was 33.72 (SD = 9.05), close to norms of working adults (M = 33.75, SD = 9.2). SAT was correlated with SAS, r = .662.6 Maternal anxiety symptoms were not correlated with infant gender, maternal education, age, or ethnicity. A histogram of SAT (http://nyspi.org/Communication_Sciences/index.html, Appendix E) shows a skewed distribution (skewness = .72, SE = .22). Representation at the high and low ends are adequate for our conclusions, but the high end is more differentiated (extending to SD above the mean) than is the low end (extending to SD below the mean). The distribution mean is approximately 34, the Mdn is 32, and the mode is 26 to 28. Using an interquartile range, a score of 27 and below defines the low 25% of participants; 40+ defines the upper 25%. These considerations will make our interpretation of the low anxiety-symptom pole in the nonlinear analyses more conservative. In a community sample of 1,076 women postpartum, mothers scoring higher than 1 SD above the mean on SAT (43+) were at greater risk for anxiety-related disorders (Gilboa, Granat, Feldman, Kvint, & Merlov, 2004). Our upper quartile is in this range.

Are Maternal Anxiety Symptoms Associated With Qualitative Behavioral Features?

Appendix F (http://nyspi.org/Communication_Sciences/index.html) presents the results of testing associations of anxiety symptoms with means of the behavioral scales (Appendix F1) and rates of behavioral extremes (Appendix F2, tested as percent time, except where indicated as “ever”). Regarding the means of the behavioral scales, there were no significant associations of maternal anxiety with infant means of behavioral scales [gaze, facial affect, vocal affect, engagement, touch and head orientation (http://nyspi.org/Communication_Sciences/index.html, see Appendix A for definitions of scales)]. There was one (of five possible) significant association of maternal anxiety with maternal means of behavioral scales [gaze (tested as %time), facial affect, engagement, touch, and spatial orientation]. Mothers with higher (vs. lower) anxiety symptoms gazed at infants a greater percent of the time, r = .214, p < .05.

The testing of behavioral extremes is exploratory because there is no literature on which to base hypotheses; however, our previous analysis of associations of mother and infant self- and interactive contingency with infant attachment in this dataset did yield rich findings using the approach of behavioral extremes (Beebe et al., 2010). The following infant behavioral “extremes” were tested (as %time, except where indicated as “ever”) for associations with higher anxiety: (a) negative facial affect, (b) negative vocal affect, (c) distress (facial or vocal), (d) discrepant affect (facial/vocal), (e) no touch, (f) touch own skin, (g) touch mother, (h) touch object, (i) head avert or arch, (j) avert (60–90 degrees) (ever), (k) arch (ever), (l) engagement–positive affect/gaze off, (m) engagement–look angled for escape, and (n) engagement–negative affect/gaze on. None showed significant associations with anxiety.

The following maternal behavioral extremes were tested for associations with higher anxiety: (a) negative facial affect, (b) positive facial affect (smile 2, smile 3, mock surprise), (c) interruptive touch, (d) intrusive touch, (e) loom, (f) mother positive/infant distressed, (g) woe face, and (h) chase + dodge (ever). No analyses were significant. A nonsignificant trend (p = .08) toward more negative maternal facial expressions with anxiety was evident, consistent with our hypothesis.

Maternal gaze was significant in one of five behavioral means tested (20% of analyses); however, once measures of means and behavioral extremes are combined, many maternal tests were run. This maternal gaze finding will need replication.

Are Higher Maternal Anxiety Symptoms Associated With Altered Contingencies?

In this section, we present contingency findings associated with higher SAT scores, whether linear or nonlinear. Using multilevel time-series analysis, we report the effects of SAT on estimates (β) of self- and interactive contingency. Nonlinear effects refer to the higher portion of the effects (the right-hand portion of the graphed effects). For example, in linear findings, mothers with higher maternal anxiety symptoms may show altered contingency (higher or lower) compared to mothers scoring lower in symptoms; in nonlinear findings, mothers with higher symptoms may show altered contingency (higher or lower) compared to mothers scoring midrange in symptoms. Next, both sets of effects are summarized as contingency patterns associated with higher maternal anxiety symptoms. These linear and nonlinear estimates are presented in Table 1 and are illustrated in Figure 1. Significant effects in Table 1 indicate that when mothers had elevated anxiety symptoms (by 1 SD from the mean), contingency is lowered (negative sign), or heightened (positive sign).

TABLE 1.

Maternal Anxiety Trait (SAT) and Self- and Interactive Contingency: Linear and Nonlinear Effects

| INFANT |

MOTHER |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE β | p | β | SE β | p | ||

| Pattern 1 | Infant Gaze | Mother Gaze | |||||

| I→I | 3.634 | .069 | <.001 | M→M | 2.450 | .113 | <.001 |

| SAT × I→I | −.038 | .064 | .553 | SAT×M→M | .028 | .093 | .761 |

| SAT2 × I→I | −.028 | .045 | .534 | SAT2 ×M→M | .074 | .073 | .310 |

| M→I | .640 | .164 | <.001 | I→M | .618 | .096 | <.001 |

| SAT ×M→I | −.081 | .138 | .559 | SAT × I→M | −.002 | .084 | .981 |

| SAT2 × M→I | −.024 | .097 | .807 | SAT2 × I→M | −.027 | .061 | .658 |

| Pattern 2 | Infant Facial Affect | Mother Facial Affect | |||||

| I→I | .626 | .009 | <.001 | M→M | .545 | .010 | <.001 |

| SAT × I→I | −.016 | .009 | .089 | SAT×M→M | .002 | .009 | .780 |

| SAT2 × I→I | −.011 | .006 | .077 | SAT2 ×M→M | .002 | .007 | .766 |

| M→I | .059 | .012 | <.001 | I→M | .154 | .010 | <.001 |

| SAT × M→I | .032 | .010 | .002 | SAT × I→M | −.003 | .010 | .762 |

| SAT2 × M→I | −.006 | .008 | .451 | SAT2 × I→M | −.014 | .006 | .027 |

| Pattern 3 | Infant Vocal Affect | Mother Facial Affect | |||||

| I→I | .632 | .010 | <.001 | M→M | .620 | .009 | <.001 |

| SAT × I→I | .004 | .010 | .672 | SAT×M→M | .008 | .008 | .313 |

| SAT2 × I→I | −.029 | .007 | <001 | SAT2 ×M→M | −.001 | .006 | .820 |

| M→I | .003 | .001 | <.001 | I→M | 1.714 | .188 | <.001 |

| SAT ×M→I | .001 | .0004 | .254 | SAT × I→M | .153 | .183 | .403 |

| SAT2 × M→I | −.001 | .0004 | .036 | SAT2 × I→M | −.315 | .140 | .025 |

| Pattern 4 | Infant Vocal Affect | Mother Touch | |||||

| I→I | .660 | .010 | <.001 | M→M | .751 | .007 | <.001 |

| SAT × I→I | .018 | .009 | .050 | SAT ×M→M | .016 | .006 | .011 |

| SAT2 × I→I | −.035 | .007 | <001 | SAT2 ×M→M | −.013 | .005 | .006 |

| M→I | .0003 | .002 | .871 | I→M | .023 | .036 | .526 |

| SAT × M→I | −.004 | .002 | .009 | SAT × I→M | −.062 | .035 | .076 |

| SAT2 × M→I | .002 | .001 | .049 | SAT2 × I→M | .060 | .027 | .028 |

| Pattern 5 | Infant Touch | Mother Touch | |||||

| I→I | .791 | .007 | <.001 | M→M | .739 | .007 | <.001 |

| SAT × I→I | −.003 | .006 | .577 | SAT ×M→M | .010 | .039 | .010 |

| SAT2 × I→I | −.016 | .005 | .001 | SAT2 ×M→M | −.007 | .005 | .152 |

| M→I | .004 | .002 | .015 | I→M | .101 | .039 | .010 |

| SAT ×M→I | .0004 | .001 | .781 | SAT × I→M | .016 | .034 | .640 |

| SAT2 × M→I | −.001 | .001 | .236 | SAT2 × I→M | −.016 | .028 | .575 |

| Pattern 6 | Infant Head | Mother Spatial | |||||

| I→I | .677 | .010 | <.001 | M→M | .747 | .010 | <.001 |

| SAT × I→I | .010 | .008 | .200 | SAT ×M→M | −.008 | .007 | .268 |

| SAT2 × I→I | −.020 | .005 | <001 | SAT2 ×M→M | −.021 | .006 | <001 |

| M→I | −.022 | .021 | .301 | I→M | −.006 | .003 | .100 |

| SAT ×M→I | −.010 | .017 | .568 | SAT ×I→M | −.002 | .003 | .460 |

| SAT2 × M→I | .020 | .015 | .159 | SAT2 × I→M | .001 | .002 | .735 |

Notes. SAT = Spielberger Anxiety Trait. Scale was centered by its mean. Standardized estimated fixed effects of maternal anxiety, and effects of anxiety in interaction with mother self- and interactive contingency (M → M/SAT, I → M/SAT) based on the mother “multilevel basic models” (see http://nyspi.org/Communication_Sciences/index.html, Appendix D). Standardized estimated fixed effects of maternal anxiety, and effects of anxiety in interaction with infant self- and interactive contingency (I → I/SAT, M → I/SAT) based on the infant “multilevel basic models” (see http://nyspi.org/Communication_Sciences/index.html, Appendix D). All parameter entries are maximum likelihood estimates fitted using SAS GLIMMIX Macro. All βs are standardized. Both anxiety as a linear effect and its linear conditional effect on self- and interactive contingency were included in all nonlinear models, but are not presented here. Pattern 2 indicates that when mothers had elevated anxiety symptoms, infant interactive contingency was heightened by .032; when mothers had both elevated and lowered anxiety symptoms (by 1 SD above and below the mean), maternal interactive contingency was lowered by −.014. Significant effects are in bold.

Figure 1.

- Summary of all linear (L) and nonlinear (NL) (Table 1) associations of maternal anxiety (SAT, Spielberger Trait) with self- and interactive contingency; NL findings for high end of anxiety only; L+ NL indicates effects that are both linear and nonlinear; Face = Facial Affect, VcA = Vocal Affect, Tch = Touch, I Head = Infant Head Orientation, M Sptl = Mother Spatial Orientation.

- I → M= Infant behavior (lagged) predicts Mother behavior (current second), i.e., “Mother coordinates with Infant;” M → I= Mother behavior (lagged) predicts Infant behavior (current second), i.e., “Infant coordinates with Mother.”

- ---> As maternal anxiety increases, contingency is lower, by multi-level regression models.

- → As maternal anxiety increases, contingency is higher, by multi-level regression models.

- If NO ARROW: No significant effects of maternal anxiety.

- (1)-(6) indicate the 6 modality pairings examined, grouped by domains: attention (pattern 1), affect (2, 3), mother touch (4, 5), spatial orientation (6).

- ↑ Indicates greater percent time mother gazing at infant face in more anxious mothers.

In Figure 1, arrows which curve from infant to mother represent maternal interactive contingency (vice versa for infant); arrows which curve back into one partner’s behavior represent self-contingency. The notation I → M for interactive contingency indicates that lagged infant behavior in the prior few seconds predicts maternal behavior in the current moment: Mother contingently coordinates with infant (vice versa: M → I). Broken arrows represent findings in which higher anxiety symptoms generated lowered contingency values; unbroken arrows represent findings in which higher anxiety symptoms generated heightened contingency values (compared to lower anxiety symptoms for linear equations; compared to midrange anxiety symptoms for nonlinear equations).The absence of arrows represents no effects of anxiety symptoms.

Brackets in margins of Figure 1 demarcate four domains: attention (Pairing 1), affect (Pairings 2, 3), mother touch in relation to infant behavior (Pairings 4, 5), and orientation (Pairing 6). The notation L indicates linear effects, and NL denotes nonlinear effects. Where both L and NL effects are significant, the L relation characterizes more of the group than does the NL.

Pairing 1: Infant Gaze–Mother Gaze: Self-contingency: no findings; Interactive contingency: no findings.

Pairing 2: Infant Facial Affect–Mother Facial Affect: Self-contingency: no findings; Interactive contingency: Mothers with higher (vs. midrange) anxiety symptoms lowered their facial coordination with infant facial affect, but infants of more (vs. less) symptomatic mothers showed the opposite pattern of heightened facial coordination with maternal facial affect. Table 1 shows that when mothers had elevated anxiety symptoms (by 1 SD above the mean), maternal interactive contingency was lowered by −.014, and infant interactive contingency was heightened by .032.

Pairing 3: Infant Vocal Affect–Mother Facial Affect: Self-contingency: With higher (vs. midrange) maternal anxiety symptoms, infant vocal affect self-contingency was lowered; Interactive contingency: Mothers with higher (vs. midrange) anxiety symptoms lowered facial coordination with infant vocal affect, and their infants likewise lowered vocal affect coordination with mother facial affect.

Pairing 4: Infant Vocal Affect–Mother Touch: Self-contingency: With higher maternal anxiety symptoms, infant vocal affect self-contingency was both (a) heightened [compared to infants of more (vs. less) symptomatic mothers] and (b) lowered (compared to infants of midrange anxiety scoring mothers). With higher anxiety symptoms, maternal touch self-contingency was both (a) heightened (compared to mothers scoring lower in symptoms) and (b) lowered (compared to mothers scoring midrange); Interactive contingency: Mothers with higher (vs. midrange) anxiety symptoms heightened their touch coordination with infant vocal affect. Infants of more symptomatic mothers (a) lowered their vocal affect coordination with maternal facial affect (compared to infants of lower symptom mothers) and (b) heightened their vocal affect coordination with maternal facial affect (compared to infants of midrange symptom scoring mothers).

Pairing 5: Infant Touch–Mother Touch: Self-contingency: With higher (vs. midrange) maternal anxiety symptoms, infant touch self-contingency was lowered, and with higher (vs. lower) maternal symptoms, maternal touch self-contingency was heightened; Interactive contingency: no findings.

Pairing 6: Infant Head Orientation–Mother Spatial Orientation: Self-contingency: With higher (vs. midrange) maternal anxiety symptoms, self-contingency of both infant head orientation and maternal spatial orientation were lowered; Interactive contingency: no findings.

In summary, of equations run (48 linear and nonlinear), 33% (16 of 48) were significant, a nonrandom pattern of findings. Of infant equations run, 37.5% (9 of 24) were significant; of mother equations run, 29.2% (7 of 24). Of significant equations, self-contingency accounted for 56.25%.

Are Alterations in Contingency Associated With the Low Pole of Anxiety Symptom Scores Similar to Those Associated With the High Pole? Nonlinear Analyses

The previous section described findings of dyads in which mothers endorsed higher anxiety symptoms. We now return to the nonlinear analyses of Table 1, graphed in Web site Appendix G (http://nyspi.org/Communication_Sciences/index.html), to interpret findings at the low anxiety symptom pole. Where significant, nonlinear analyses show that alterations in contingencies associated with movement toward the low pole are similar (in direction, but not necessarily in absolute amount) to those associated with the high pole (vs. dyads with midrange scores). Of the significant equations, 69% (11 of 16) were nonlinear.

Pairing 1: Infant Gaze–Mother Gaze: Self-contingency: no nonlinear finding; Interactive contingency: no nonlinear finding.

Pairing 2: Infant Facial Affect–Mother Facial Affect: Self-contingency: no nonlinear finding; Interactive contingency: As maternal anxiety symptoms were elevated (by 1 SD from the mean) toward the high pole, and lowered (by 1 SD) toward the low pole, mothers showed similar decreases in facial coordination with infant facial affect (vs. mothers scoring midrange in anxiety symptoms). This effect is more pronounced at the high symptom end (http://nyspi.org/Communication_Sciences/index.html, Appendix G).

Pairing 3: Infant Vocal Affect–Mother Facial Affect: Self-contingency: As maternal anxiety symptoms moved toward high and low poles, infants showed similar decreased vocal affect self-contingency (vs. infants whose mothers scored midrange in symptoms), more pronounced at the high pole; Interactive contingency: As maternal anxiety symptoms moved toward the high and low poles, (a) mothers showed decreased facial coordination with infant vocal affect, and (b) infants showed decreased vocal affect coordination with maternal facial affect. These effects are more pronounced at the high pole.

Pairing 4: Infant Vocal Affect–Mother Touch: Self-contingency: Compared to dyads in which mothers scored midrange in anxiety symptoms, as symptoms moved toward high and low poles, (a) infants showed decreased vocal affect self-contingency, an effect more pronounced at the high pole; and (b) mothers showed very subtle decreased touch self-contingency; Interactive contingency: Compared to dyads in which mothers scored midrange in anxiety symptoms, as symptoms moved toward high and low poles, (a) infants showed increased vocal affect coordination with maternal touch; and (b) mothers showed increased touch coordination with infant vocal affect.

Pairing 5: Infant Touch–Mother Touch: Self-contingency: As maternal anxiety symptoms moved toward high and low poles, infants showed subtle decreases in touch self-contingency (vs. infants whose mothers scored midrange in symptoms). Because the effect is so subtle at the low pole, this effect is interpreted at the high pole only (http://nyspi.org/Communication_Sciences/index.html, Appendix G); Interactive contingency: no nonlinear finding.

Pairing 6: Infant Head Orientation–Mother Spatial Orientation: Self-contingency: Compared to dyads in which mothers scored midrange in anxiety symptoms, as symptoms moved toward high and low poles, (a) infants showed very subtle decreases in head orientation self-contingency, and (b) mothers showed decreases in spatial orientation self-contingency. Because the effect is so subtle at the low pole, this effect on maternal self-contingency is interpreted at the high pole only; as symptoms increase, the decrease in self-contingency accelerates; Interactive contingency: no nonlinear finding.

DISCUSSION

We investigated the effects of maternal self-reported trait anxiety symptoms on mother–infant face-to-face communication at 4 months. After noting descriptive information, we describe the qualitative features of behavior associated with maternal anxiety symptoms. The meaning of heightened and lowered contingencies is then addressed, as is our hypothesis that distress biases the communication system toward both heightened self- and interactive contingencies (in some modalities) and lowered self- and interactive contingencies (in others). We then describe the picture of higher maternal anxiety symptoms in relation to contingencies across the modalities of attention, affect, touch, and spatial orientation. Our question of whether contingency patterns of dyads at the low pole of anxiety symptoms look similar to those at the high pole is addressed next. We then interpret our self- and interactive contingency findings as forms of self- and interactive regulation. Finally, limitations of the study, and implications for early intervention, are noted.

Descriptive Information

In our low-risk community group, the incidence of anxiety symptoms was no different from that of the general population. Associations between anxiety symptoms and infant gender, and maternal age, education, and ethnicity, were absent.

Qualitative Features of Behavior Associated With Maternal Anxiety Symptoms

Only one qualitative feature of behavior was identified: mothers with higher (vs. lower) anxiety-related symptoms spent a greater percentage of time looking at their infants’ faces. A nonsignificant trend (p = .08) toward more negative maternal facial expressions is consistent with clinical observation in this group as well as with our hypothesis, but would require replication. Otherwise, higher (vs. lower) symptom dyads did not differ in qualitative behavioral features (see http://nyspi.org/Communication_Sciences/index.html Appendices F1 & F2). The absence of qualitative features may reflect the low-risk nature of this community sample.

Hypotheses Regarding Interactive and Self- Contingency

Differences were found in self- and interactive contingency rather than in behavioral qualities, a striking finding (also see Beebe et al., 2007). Contingency addresses the process of relating over time whereas behavioral qualities address specific rates of behaviors, taken out of time. Regarding interactive contingency, findings were consistent with our hypothesis that across the system of both partners and all communication modalities, maternal anxiety symptoms bias the system toward both heightened values (in some modalities) and lowered values (in others). Consistent with our prediction, mothers with anxiety-related symptoms lowered their interactive contingencies in affective modalities: They lowered facial affect coordination with infant facial and vocal affect. We anticipated that these mothers would show heightened interactive contingencies in gaze; instead, we found that mothers spent more time gazing at their infants. As anticipated, we found heightened maternal touch coordination, and infants of mothers with anxiety-related symptoms heightened their facial affect coordination with maternal facial affect. However, not consistent with our prediction, infants lowered their vocal affect coordination with maternal facial affect. We did not substantiate our prediction that infants would show lowered contingency with mothers in modalities other than affect. Instead, we found a complex pattern involving infant vocal affect and maternal touch (discussed later).

Regarding self-contingency, we hypothesized both lowered and heightened values associated with anxiety symptoms; instead, infant self-contingency was lowered in four (of five) significant equations. In the only exception, infants heightened self-contingency of vocal affect paired with maternal touch. Thus, infant activity rhythms of facial and vocal affect, touch, and head orientation were largely “destabilized” when mothers reported anxiety-related symptoms. Lowered self-contingency indicates a lowered ability to anticipate one’s own ongoing behavioral stream, so that one knows less what to expect of oneself. The cues by which one knows oneself are less predictable, yielding a decreased sense of coherence over time. In our prior work, lowered infant self-contingency was evident with maternal depression, self-criticism, and dependency (Beebe et al., 2007; Beebe et al., 2008a).

Consistent with our hypothesis, mothers with anxiety-related symptoms showed self-contingency patterns that were both heightened [mother touch paired with infant touch and vocal affect (L)], and lowered [spatial orientation, and mother touch paired with infant vocal affect (NL), consistent with an optimum midrange model of contingency. Maternal dysregulated inner state can thus manifest in self-contingencies that are both too high and too low. We now turn to a detailed discussion of findings.

The Picture of Higher Maternal Anxiety Symptoms

Gaze

Although we conjectured that mothers with anxiety symptoms would show heightened gaze contingency, instead they showed heightened time looking at their infants’ faces. This finding may reflect maternal efforts to monitor “what is happening,” out of fear that the contact “will not work,” or in an effort to see if “everything is okay.” It is a vigilance consistent with an overly aroused maternal state. Gaze vigilance toward the face of the partner is consistent with the literature on anxiety documenting that attentional vigilance for emotional faces is higher in anxious individuals (Bradley & Mogg, 1999; Fox, Russo, & Dutton, 2002).

Facial affect

Consistent with our prediction (also see Kaitz & Maytal, 2005), mothers with anxiety symptoms lowered their facial coordination with infant facial affect, an affective “withdrawal.” In contrast, their infants showed the opposite, a heightened facial coordination with maternal facial affect, indicating an affective “approach” or “vigilance.” This finding is consistent with our prediction, and with de Rosnay et al.’s (2006) suggestion that infants of symptomatic mothers may be overly sensitive to maternal affective communication. This infant “facial approach”–maternal “facial withdrawal” is a pattern of interpersonal conflict. Mothers may need to withdraw from infant facial affect to protect their own overly aroused inner state, but infants may need to be facially vigilant in a compensatory effort to monitor and “stay with” a mother who is affectively withdrawn.

Maternal gaze/face discordance

It is striking that mothers with anxiety symptoms showed more time gazing at infants’ faces, yet lowered their facial coordination with infant facial affect: a form of intermodal discordance likely to be confusing to infants. To illustrate, although these mothers looked more at infant faces, when infants showed happy faces, these mothers were less likely to show delight; when infants showed distressed faces, these mothers were less likely to show facial empathy. Thus, these mothers vigilantly monitored infants visually, but they did not emotionally respond empathically to infants. This maternal facial–emotional withdrawal is construed as a “violation” of a universal expectation that one’s emotional state will be acknowledged through a correlated change in the partner (Tronick, 1989), yielding a concordant state. Vigilant visual monitoring, without empathic emotional response, suggests that mothers may be “looking through” the infants’ faces, as if the infant is not “seen” or experienced, consistent with Kaitz and Maytal’s (2005) description that symptomatic mothers seem self-absorbed or detached. This maternal pattern may be a self-protective effort to dampen arousal and partially disengage, to avoid further distress.

Maternal facial affect–infant vocal affect

Mothers with anxiety symptoms and their infants both lowered their coordination in this pattern, a mutual affective withdrawal likely sensed by each partner. Infants also showed lowered self-contingency of vocal affect, a self-destabilization. The lowered infant self-predictability may be more difficult to “read” and thus may contribute to lowered maternal coordination. Integrating the aforementioned finding, these mothers lowered their facial coordination with both infant facial and vocal affect—a striking maternal emotional withdrawal. Lowered maternal facial coordination decreases infant interactive “efficacy:” It is harder for infants to anticipate consequences of their facial/vocal affect on mothers’ facial affect.

Infant discordant coordination with mother’s face

Integrating the two infant facial and vocal findings noted earlier, infants heightened their facial affect coordination (vigilance), but dampened their vocal affect coordination (withdrawal), with mother’s face. Infants may become facially vigilant to maternal facial affect to resolve the conflicting maternal signals of heightened gaze but dampened facial coordination or to compensate for maternal emotional withdrawal and their own lowered efficacy. Yet, infants dampened their vocal affect coordination with maternal facial affect, an inhibition or withdrawal. The two findings together generate a remarkable infant intrapersonal intermodal discordance, or conflict. The combination of maternal gaze/facial affect discordance and infant facial/vocal affect discordance can be seen as a mutual perplexity, a mutual affective ambivalence,7 confusing to both partners. This finding elucidates with unique specificity how mothers and infants together may construct communication disturbances.

Maternal touch–infant vocal affect

In our prior across-group analysis of these mothers and infants (Beebe et al., 2008b), we documented that mothers coordinate their touch with infant vocal affect. As infant vocal affect becomes more positive, maternal touch patterns are more affectionate, and vice versa. The “average” infant across the group, however, did not reciprocally coordinate vocal affect with maternal touch.

Here, we document that with increasing anxiety symptoms, as infant vocal affect becomes more positive, mothers are even more likely to touch with affectionate patterns; vice versa, as infant vocal affect inevitably becomes more negative, mothers are even more likely to touch with less affectionate patterns (see Figure 1). It is striking that mothers dampened their facial coordination with infant vocal affect (as noted earlier), but heightened their touch coordination with infant vocal affect, an intermodal discordance.

We suggest that this higher maternal touch coordination reflects a compensatory maternal effort to make contact, consistent with reports that maternal touch “repairs” the effects of the still-face experiment on the infant (Stack & Muir, 1992). It also may reflect a tendency toward “doing” rather than “feeling,” in an attempt to ward off helplessness (Chorpita & Barlow, 1998). Most mothers with anxiety symptoms also heightened their touch self-contingency, a self-stabilization. Thus, mothers with anxiety symptoms have a more self-stable and more highly coordinated touch pattern. This touch pattern may be more “readable” by the infant, and may indicate a maternal compensatory effort to “repair” the interaction, which is disrupted in the affective modalities, as noted earlier. Nevertheless, this “repair” falls apart when infants inevitably become vocally distressed.

It is striking that infants of mothers with anxiety symptoms showed coordination with maternal touch whereas the “average” infant across the group did not (Beebe et al., 2008b). Moreover, most infants lowered their coordination with maternal touch, a withdrawal. This is a conflictual interactive contingency pattern of maternal “approach:” infant “withdrawal.” Thus, most infants withdrew from mothers in their compensatory touch coordination efforts. Most infants also heightened their self-contingency of vocal affect, a self-stabilization.

However, at the high end of symptom scores, in this mother touch–infant vocal affect pairing, infants showed a heightened coordination, a vigilance, and a lowered self-contingency, a destabilization. Thus, at the high end of scores, infants and mothers generated a mutual interactive vigilance. We interpret mutual vigilance as a dyadic attempt to create more predictability in the context of stress (Jaffe et al., 2001), a mutual compensatory effort.

Mother spatial orientation–infant head orientation

Although there were no interactive contingency findings in this pattern, both mothers and infants showed lowered self-contingency, a mutual orientational destabilization. Thus, as mothers with anxiety symptoms moved among spatial orientations of sitting upright, to leaning forward, to looming in, they were less predictable. This lowered predictability disturbs the “spatial frame” of the face-to-face encounter, a background sense of spatial structure that mothers usually provide. It also generates infant difficulty in decoding and predicting maternal behavior, decreasing infant sense of agency. Similarly, as their infants oriented their heads in a continuum from enface toward arch, they were less predictable, generating less clear signals to mothers as to whether they were staying enface, “going out” toward arch, or “coming back in.”

In summary, mothers with anxiety-related symptoms vigilantly monitored infants visually, but withdrew from contingently coordinating with infant affective ups and downs, and thus did not emotionally respond empathically to infants. Infants were intently looked at, but not emotionally responded to, as if mothers were “looking through” them. This picture fits descriptions of anxious mothers in the literature as overaroused and fearful, leading to vigilance, but simultaneously emotionally withdrawn and less sensitive, dealing with their fear and overarousal through emotional distancing (Barlow, 1991; Kaitz & Maytal, 2005; Feldman et al., 1997; Nicol-Harper et al., 2007; Warren et al., 2003). For their part, infants heightened facial affect coordination (vigilance), but dampened vocal affect coordination (withdrawal), with mother’s face, a pattern of conflict regarding mother’s face. We interpret the combination of maternal gaze/facial affect discordance and infant facial/vocal affect discordance as a mutual perplexity, a mutual affective ambivalence. In the context of these affect and visual attention-regulation difficulties, mothers heightened their contingent touch coordination with infant vocal affect, perhaps a compensatory effort, but infants mostly withdrew from coordinating with maternal touch. Finally, both mothers and infants exhibited a mutual orientational destabilization, generating difficulty in each partner in predicting what the other will do next, in spatial orientation.

We suggest that these maternal patterns of emotional withdrawal, attentional/facial discordance, and maternal discordant coordination with infant vocal affect are highly unusual. Moreover, these patterns introduce a “primary disturbance” similar to, but not as extreme as, the “still-face” experiment (Tronick, 1989). The remarkable infant conflicting responses to maternal facial affect is reminiscent of Weinberg and Tronick’s (1996) description of infant ambivalence during the reunion episode following the still-face. In the reunion episode (compared to baseline play), infants show even more joyful faces, but they also continue the increased incidence of sadness and anger shown during the still-face. Like Weinberg and Tronick (1996), our findings also document remarkable differentiation, specificity, and discordance in infant intermodal emotional organization, which can be described as infants in conflict.

Evaluating Low and High Poles of Maternal Anxiety Symptoms

Because self-report scales are vulnerable to denial (Shedler et al., 1993), we hypothesized that very low anxiety-symptom scores may be associated with communication difficulties similar to those of very high scores. Testing this notion with nonlinear analyses, 69% of findings were nonlinear. Where mothers endorsed either high or low symptom poles, dyads showed roughly similar patterns of altered contingency, compared to dyads in which mothers had midrange anxiety-symptom scores. Next, we note only those patterns with significant nonlinear findings.

Regarding maternal interactive contingency, mothers at both high and low poles of anxiety symptoms (more pronounced at the high pole) dampened facial coordination with infant facial/vocal affect shifts, but heightened touch coordination with infant vocal affect. Regarding infant interactive contingency, infants of mothers at both high and low poles lowered vocal affect coordination with maternal facial affect (more pronounced at the high pole), but heightened vocal affect coordination with maternal touch. Regarding maternal self-contingency, mothers at both the high and low poles similarly showed very subtle decreases in touch self-contingency, and decreases in spatial orientation self-contingency (at the high pole only). Regarding infant self-contingency, infants of mothers at both high and low poles showed decreases in vocal affect self-contingency (more pronounced at the high pole), subtle decreases in touch self-contingency (at the high pole only), and subtle decreases in head-orientation self-contingency.

Although we are intrigued by these nonlinear findings indicating difficulty at the very low pole of anxiety symptoms, we remain cautious. Some mothers reporting very few or no symptoms may indeed be less vulnerable whereas others may be using denial. Long-term consequences for infant development in dyads in which mothers have very low distress scores are unclear (Lyons-Ruth et al., 1986). Because of the clinical significance of maternal denial of distress, and disagreement as to its existence and consequences, further research is needed (Pickens & Field, 1993; Tronick et al., 1997; Weinstein & Kahn, 1955).

Implications of Contingency Findings for the Concept of “Regulation”

The concept of regulation is defined differently in varying research traditions (Campos, Frankel, & Camras, 2004; Cole, Martin, & Dennis, 2004; Davidson, Jackson, & Kalin, 2000). Our contingency measures, assessing predictability of behavior over time, qualify as one definition of regulation (Cohn & Tronick, 1988; Jaffe et al., 2001). Comparing Cole et al.’s (2004) review of definitions of regulation, our approach fits their “analysis of temporal relations” using time-based methods, illustrated with the work of Cohn and Tronick (1988): “well-suited to inferring that each person’s behavior regulates that of the partner” (Cole et al., 2004, p. 324). Thus, we construe our self- and interactive contingency findings as forms of self- and interactive regulation and as relevant to that literature (see Beebe & Lachmann, 2002; Cohn & Tronick, 1988; Sander, 1977; Stern, 1985; Tronick, 1989). Although this approach is familiar for interactive regulation, it is less so for self-regulation (but see Downey & Coyne, 1990; Thomas & Malone, 1979; Warner, 1992).

Limitations of the Study