Abstract

Importance

Mobile smart phones are rapidly emerging as an effective means of communicating with many Americans. Using mobile applications, they can access remote databases, track time and location, and integrate user input to provide tailored health information.

Objective

A smart phone mobile application providing personalized, real-time sun protection advice was evaluated in a randomized trial.

Design

The trial was conducted in 2012 and had a randomized pretest-posttest controlled design with a 10-week follow-up.

Setting

Data was collected from a nationwide population-based survey panel.

Participants

The trial enrolled a sample of n=604 non-Hispanic and Hispanic adults from the Knowledge Panel® aged 18 or older who owned an Android smart phone.

Intervention

The mobile application provided advice on sun protection (i.e., protection practices and risk of sunburn) and alerts (to apply/reapply sunscreen and get out of the sun), hourly UV Index, and vitamin D production based on the forecast UV Index, phone's time and location, and user input.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Percent of days using sun protection and time spent outdoors (days and minutes) in the midday sun and number of sunburns in the past 3 months were collected.

Results

Individuals in the treatment group reported more shade use but less sunscreen use than controls. Those who used the mobile app reported spending less time in the sun and using all protection behaviors combined more.

Conclusions and Relevance

The mobile application improved some sun protection. Use of the mobile application was lower than expected but associated with increased sun protection. Providing personalized advice when and where people are in the sun may help reduce sun exposure.

Introduction

The rapid proliferation and enormous reach of mobile computing devices, including smart phones and tablet computers, are transforming the communication experience.1,2 An increasing number of adults are using them to run mobile apps and access the Internet from anywhere,3,4 including to obtain health information.2

While there is no comprehensive theory explaining how mobile interventions improve health (i.e., mHealth),1,5,6 they may be effective for several reasons. Mobile devices can enhance engagement with health information1,5 by proactively, unobtrusively, confidentially, and repeatedly reaching out to users, requesting their attention,1,7,8 creating an urgency to respond,9 and delivering advice in real-time, on their schedules, 24/7, and anywhere.1,8 These properties should elevate the ecological validity of the health information by tailoring it to each user “in-the-moment” when and where it is most meaningful.1,5,7,10 They should creating social support through its presence, relevancy, urgency, and interactivity and ability to increase adults' accountability, deliver emotional support7 and create a sense of volition, choice, and control.11 Moreover, mobile devices can manage time and location dependences, access remote databases,12 and deliver reminders for action. All of these attributes could be used to improve self-efficacy and response efficacy13 and provide cues to action14 to motivate risk-reduction behaviors.

In this project, we conducted the first evaluation of a mobile application that provided sun protection advice to reduce the risk of skin cancer. It is estimated that approximately 2 million non-melanoma skin cancers (i.e., basal and squamous cell carcinoma) and 76,100 cutaneous malignant melanoma (43,890 males; 32,210 females) will be diagnosed in 2014,15 costing $1.4 billion dollars annually for treatment16,17 It was hypothesized that the mobile application would increase sun protection practices and decrease sunburn prevalence by improving sun protection norms, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and intentions.13

Methods

Sample

Participants were recruited from the Knowledge Panel®, a survey panel representative of the U.S. adult population administered by GfK, Inc. GfK identified panel members that met eligibility requirements (i.e., non-Hispanic or Hispanic white, 18 years of age or older, and a U.S. resident) and invited them to participate through their online system. Adults were screened on smart phone ownership (participation was limited to adults with Android handsets) and eligible individuals signed a consent form and completed the baseline survey online. Recruitment occurred from July 10 – 23, 2012. Participants received credit in the Knowledge Panel® system.

Procedures

The trial involved a randomized pretest-posttest controlled design. Potential participants were randomized invited to join the study. Those that consented and completed the baseline survey in GfK's online system were enrolled. Participants assigned to the treatment group received instructions through the online system to download, install and use the Solar Cell mobile app. An online guide was provided, along with email and telephone technical assistance. Seven weeks after randomization, treatment group participants were sent a reminder through the online system to use the mobile app. Ten weeks after the recruitment period began (Sept 18), all participants received the invitation for the posttest survey; posttesting concluded on October 3rd. A small group of participants failed to indicate they had completed their pretest in the online system so they did not receive the posttest invitation. However, they were eligible and randomized, so they were re-contacted for posttesting in December. All procedures and forms were approved by the Western Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Solar Cell Mobile App

The Solar Cell mobile app was available for Android smart phones and has been described in detail elsewhere.18 In brief, it provided personalized sun protection advice based on: 1) 5-day hour-by-hour UV Index forecasts issued daily by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for each 0.5° latitude-longitude grid in North America (approximately 40 mi. × 40 mi.), 2) time and location from the phone, and 3) personal information from the user (i.e., skin phenotype, height, weight, age, clothing coverage, use of sunscreen and its SPF, and use of medications increasing sun sensitivity). Using algorithms based on published literature, Solar Cell provided the following advice: a) risk of sunburn (time until sunburn and level of risk [low, moderate, extreme]), b) time until reapplication of sunscreen, c) recommended sun protection practices (sunglasses, sunscreen, hats, protective clothing, shade, and go indoors), d) current forecasted UV Index, and e) estimated amount of vitamin D produced by the skin. Pop-up screens provided educational information. Visual and audible alerts signaled when users needed to reapply sunscreen, achieved the recommended daily dose of vitamin D, and were at extreme risk of sunburn. Users could indicate when they were in the sun, in the shade, or indoors. Risk of sunburn was adjusted for skin phenotype, use of sunscreen and shade, and being indoors.

Measures

Outcome measures assessed exposure to the midday sun, sun protection practices, and sunburn prevalence in the past 3 months at baseline and posttest, the a priori primary outcomes. The surveys were pretested to ensure the questions were understandable and easily answered, using cognitive interviewing procedures with non-Hispanic white adults (n=2 males and 3 females).

Sun Exposure and Sun Protection Practices

Sun exposure and protection practices were assessed with validated open-ended measures from the published literature. Sun exposure was measured by asking participants to report the number of days and number of hours spent in the sun between 10 am and 4 pm (solar noon ± 3 hours) in the past three months.19 Participants next reported the number of those days that they practiced each of seven sun protection behaviors, which were converted to percentage of days engaged in each practice, i.e., wearing sunscreen with sun protection factor (SPF) of 15 or higher, sunscreen lip balm with SPF 15 or higher, clothing that protected the skin from the sun, a hat with a wide brim, and sunglasses, keeping time in the sun to a minimum, and staying in the shade. The mean percent of practicing all sun protection behaviors was also calculated. Sunburn prevalence was assessed with two questions: whether participants had ever been sunburned and how many times they were sunburned in the past 3 months (defined as being red and/or painful from exposure to the sun).20

Moderators and Mediators

Potential effect moderators and theoretic mediators were measured at baseline and posttest, again using measures from the literature. Moderators included demographics, skin phenotype (based on hair color, eye color, and skin tanability),21 2-item tanning image scale (I think I look healthier when I tan; I think I look better when I tan [Cronbach's α=0.86 at baseline; 0.92 at posttest]),22 and personal history of skin cancer (has doctor ever told you that you have had skin cancer). Participants who tend to take fewer precautions, such as males and younger adults23 and those who have more sun-sensitive skin and a history of skin cancer might respond more to the mobile app's advice while tanners may resist it.

Theoretic mediators from Social Cognitive Theory24 were assessed by items created by the authors: a) descriptive norms (on the average out of 100 people like you, how many do you think will [a] get sunburned while outdoors this summer and [b] protect their skin from the sun this summer) and injunctive norms (most of my family think [a] getting a sun tan is not a good thing and [b] getting a sun tan is not a good thing [α=0.76 at baseline; 0.74 at posttest; 5-point Likert scale, 1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree]; most of my family think people should protect their skin from the sun and most of my friends think people should protect their skin from the sun [α=0.67 at baseline; 0.66 at posttest; 5-point Likert scales]), b) self-efficacy expectations (I am confident I can [a] avoid getting sunburned while outdoors in the summer sun (5-point Likert scale) and [b] practice sun safety that is wear sunscreen, protective clothing, a hat, and sunglasses the next time you go out in the sun [1=not at all confident, 4=very confident]), and c) outcome expectations (it is not so complicated to protect my skin from the sun; two items assessing fit and ease – protecting my skin from the sun fits well with my outdoor activities and it is easy to protect my skin from the sun [α=0.68 at baseline; 0.71 at posttest; 5-point Likert scales]). Intentions to spend time in the sun to get a tan and a two-item scale on sun protection - whether or not participant (a) planned (yes/no) and (b) was willing (1=very unwilling, 5=very willing) to protect skin from the sun when outdoors in the future (α=0.75 at baseline; 0.76 at posttest) were assessed.

Statistical Analysis

The effect of Solar Cell was tested by comparing percent of days practicing sun protection behaviors, time spent outdoors in the midday sun, and sunburn prevalence between treatment and control group. Comparisons were performed on posttest values, using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) and controlling for baseline values and demographic covariates (identified by stepwise elimination at p < 0.10, two-tailed). Initially, comparisons were performed on participants who completed the posttest. Then, missing values were imputed and comparisons re-run to assess effects of loss to follow-up. Potential moderators of Solar Cell's effect was probed by testing two-way interactions between the moderator (with levels as appropriate) and treatment group in the ANCOVA models. All tests were performed using p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

Results

Profile of the Sample

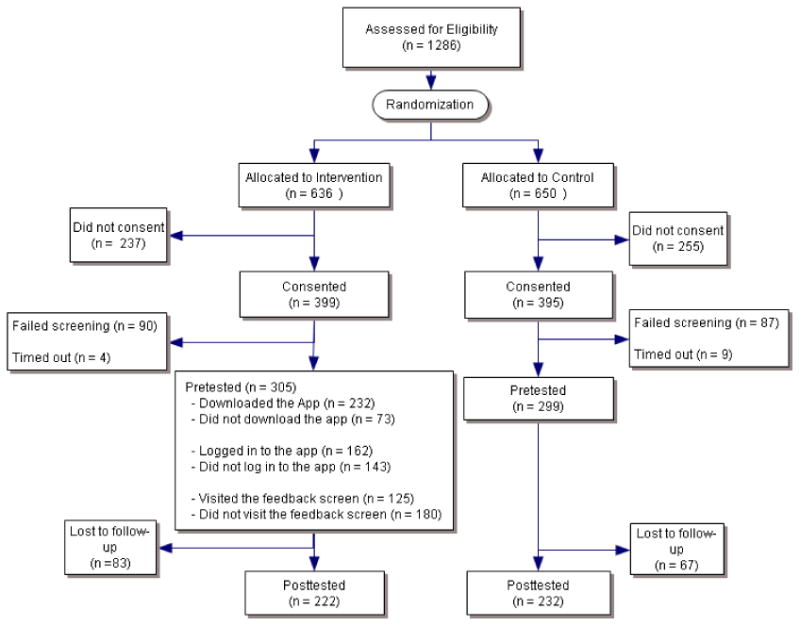

Overall, 604 individuals out of 1,286 invited were enrolled in the trial (See CONSORT diagram in Figure 1). A total of 682 individuals (n=331 in treatment group; n=351 in control group) did not consent or were deemed ineligible. Of those enrolled, 150 participants (25%; n=83 in treatment group [27%]; n=67 in the control group [22%]) were lost to follow-up at posttest, leaving 454 participants with complete data (n=222 in treatment group; n=232 in control group).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram for the trial – this shows the participation, loss, and follow-up of participants.

Participants had a diverse profile (Table 1). However, participants were younger, more educated, and more affluent and lived in large households, and fewer were Hispanic whites than in the U.S. population. Specifically, they ranged in age from 18 to 80 (68.5% under age 45) and were well educated ( . The sample contained 9.6% Hispanic whites but was equally divided on gender. Also, 24.2% had high-risk skin phenotypes (4 or 5 on Phenotypic Index) and nearly a third had been diagnosed with skin cancer. The average household size was 3.1 persons; 62.7% had incomes of $50,000 or greater); three-quarters were employed; the majority was married (nearly half had child <18 in household and three-quarters were heads of households); and about two-thirds owned their home. Participants were enrolled from 48 states (except of Idaho and Hawaii; 15.9% Northeast, $25.3% Midwest, $33.5% South, and 25.3% West), with 87.6% living in metropolitan areas. Randomization produced groups with no statistically significant differences in demographics, sun protection practices, time spent in the sun, or sunburn prevalence at baseline, except that the treatment group had fewer participants classified as head of household (73.4%) than the control group (80.3%, p<0.05). There were very few differences associated with loss to follow-up: Those completing the posttest were older (M=39.58 years, p<0.05) and more owned their home (71.4%, p<0.05) than those not completing it (M=36.79 years; 62.0%).Use of Solar Cell Mobile App

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

| Demographics | n=604 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean (SD) | 38.89 (13.15) |

| Education | <4 year college grad | 58.9% |

| 4-year college degree | 25.7% | |

| Post graduate degree | 15.4% | |

| Race / Ethnicity | White, Non-Hispanic | 90.4% |

| Hispanic | 9.6% | |

| Other, Non-Hispanic | 0.0% | |

| Gender | Female | 47.9% |

| Male | 52.1% | |

| Skin score (Phenotypic Index) | 1 = Lowest risk for skin cancer | 15.1% |

| 2 | 25.7% | |

| 3 | 35.0% | |

| 4 | 20.9% | |

| 5 = Highest risk for skin cancer | 3.3% | |

| Skin cancer | No | 69.5% |

| Yes | 30.5% | |

| Household head | No | 23.2% |

| Yes | 76.8% | |

| Household size | Mean (SD) | 3.13 (1.51) |

| Housing type | A one-family house detached from any other house | 71.4% |

| A one-family house attached to one or more houses | 6.9% | |

| A building with 2 or more apartments | 18.4% | |

| A mobile home | 3.3% | |

| Income | Less than $25,000 | 16.4% |

| $25,000 - $49,999 | 20.9% | |

| $50,000 - $99,999 | 36.2% | |

| $100,000 or more | 26.5% | |

| Marital status | Married or living with partner | 69.2% |

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated | 8.0% | |

| Never married | 22.8% | |

| MSA status | Non-Metro | 12.4% |

| Metro | 87.6% | |

| Region | Northeast | 15.9% |

| Midwest | 25.3% | |

| South | 33.5% | |

| West | 25.3% | |

| Ownership status of living quarters | Rented for cash or occupied without payment of cash rent | 31.0% |

| Owned or being bought by you or someone in your household | 69.0% | |

| Kids under 18 | No | 55.0% |

| Yes | 45.0% | |

| Employment status | Not working | 24.7% |

| Working | 75.3% |

Of the 305 people in the treatment group, 232 (76.1%) downloaded Solar Cell but only 125 (41.0%) used it (i.e., ran the app and received the feedback screen) at least once after installing it (downloading and use was detected by web servers). The majority of those who used Solar Cell (76.0%) did so 1 to 5 times (16.0% 6 to 10 times and 8.0% 11 or more times]). These users created 166 profiles and ran existing profiles 532 times.

Effect of Solar Cell Mobile App on Sun Protection Practices

Solar Cell appeared to weakly affect sun protection practices at posttest (Table 2). Individuals assigned to Solar Cell and completing the posttest reported they used shade a higher proportion of time at posttest than controls. However, individuals assigned to Solar Cell also said they used sunscreen a lower proportion of time. No other significant differences were detected. When missing posttest values were imputed, none of the sun protection practices differed significantly by experimental group.

Table 2. Results of ANCOVA models comparing outcomes by experimental group.

| Outcome Measures | Control | Treatment | Test statistic | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sunburn Prevalence in Past 3 Months | ||||

| Sunburned1, 2, 4, 6, 17 (n=450) | 28.9%† | 27.5% | χ2=1.58 | 0.21 |

| Number of sunburns1, 3 (n=445) | 0.62§ | 0.60 | F=0.03 | 0.87 |

| Time Spent Outdoors in the Sun Between 10 am and 4 pm in Past 3 Months | ||||

| Number of days1, 5, 16 (n=451) | 42.63§ | 44.86 | F=0.98 | 0.32 |

| Number of hours1, 3, 5, 16 (n=447) | 123.73§ | 123.18 | F=0.00 | 0.96 |

| Sun Protection Practices While Outdoors in the Sun Between 10 am and 4 pm in the Past 3 Months | ||||

| Percent of days wearing sunscreen with SPF 15 or greater1, 3, 5, 6, 12, 14 (n=352) | 34.5%§ | 28.6% | F=3.95 | 0.048 |

| Percent of days wearing a sunscreen lip balm with SPF 15 or greater1, 5 (n=359) | 18.9%§ | 18.7% | F=0.01 | 0.94 |

| Percent of days wearing clothing that protected the skin from the sun1, 5, 9, 17 (n=357) | 19.9%§ | 24.4% | F=1.93 | 0.17 |

| Percent of days wearing a hat with a wide brim1, 5, 7, 12, 15, 16 (n=376) | 17.3%§ | 15.8% | F=0.39 | 0.53 |

| Percent of days wearing sunglasses1, 10, 15 (n=394) | 69.9%§ | 64.8% | F=2.80 | 0.09 |

| Percent of days keeping time in the sun to a minimum1, 5, 7, 17 (n=354) | 51.0%§ | 57.2% | F=2.61 | 0.11 |

| Percent of days staying in the shade1, 5, 9, 15, 17 (n=329) | 33.7%§ | 41.0% | F=4.51 | 0.03 |

| Mean percent of days using all sun protection practices1, 5, 7, 17 (n=413) | 37.1%§ | 37.3% | F=0.02 | 0.90 |

Actual means

Least square means

Covariates controlled in the models:

Baseline value;

Age;

Education;

Race/Ethnicity;

Gender;

Skin score (Phenotypic Index);

Skin cancer;

Household head;

Household size;

Housing type;

Income;

Marital status;

MSA status;

Ownership status of living quarters;

Kids under 18;

Employment status; and

Do you agree or disagree that I look healthier and better when I tan?

Effect of Solar Cell Mobile App on Sunburn Prevalence and Time Outdoors in the Midday Sun

There was no statistically significant difference between treatment groups on posttest sunburn prevalence (Table 1). The mobile app did not affect the amount of time users spent outdoors in the midday sun. They did not spend more days or hours in the sun than controls (Table 1).

Moderators of Effect of Solar Cell on Sun Protection Practices

The effect of Solar Cell on sun protection practices was moderated by preferences for a sun tan. Participants with stronger sun tan preferences assigned to Solar Cell reported using protective clothing while outdoors on a greater percentage of days than those in the control group (F=4.48, p=0.03; eTable 1). With lower sun tan preferences, the Solar Cell group reported lower use of protective clothing than controls.

Effect of Using Solar Cell on Sun Protection and Exposure Outcomes

We probed whether the amount of Solar Cell usage was predictive of outcomes, defining use as whether participants ran the mobile app and received thefeedback screen, which provided the sun safety advice. Analyses were conducted only within the treatment group on participants completing the posttest. Individuals who used Solar Cell also reported a larger mean percentage of time practicing all sun protection behaviors combined than non-users (Table 3). Use of Solar Cell was unrelated to sunburn prevalence, although means did suggest that participants who used it had fewer sunburns than those who did not (Table 3). Participants who used the app spent a larger percentage of days keeping their time in the sun to a minimum and fewer hours outdoors in the midday sun (but not fewer days) than those who did not use it (Table 3).

Table 3. Results of ANCOVA models comparing outcomes by whether participant used Solar Cell.

| Outcome Measures | Use of Solar Cell* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did Not Use | Used | Test statistic | p-value | |

| Sunburn Prevalence in the Past 3 Months | ||||

| Sunburned1, 2, 4, 6, 17 (n=219) | 32.3%† | 20.7% | χ2=2.34 | 0.13 |

| Number of sunburns1, 3 (n=218) | 0.78§ | 0.43 | F=3.35 | 0.07 |

| Time Spent Outdoors in the Sun Between 10 am and 4 pm in the Past 3 Months | ||||

| Number of days1, 5, 16 (n=221) | 45.77§ | 41.67 | F=1.60 | 0.21 |

| Number of hours1, 3, 5, 16 (n=218) | 135.30§ | 98.66 | F=5.89 | 0.02 |

| Sun Protection Practices While Outdoors in the Sun Between 10 am and 4 pm in the Past 3 Months | ||||

| Percent of days wearing sunscreen with SPF 15 or greater1, 3, 5, 6, 11, 14 (n=171) | 26.5%§ | 29.9% | F=0.63 | 0.43 |

| Percent of days wearing a sunscreen lip balm with SPF 15 or greater1, 5 (n=176) | 17.7%§ | 17.5% | F=0.00 | 0.96 |

| Percent of days wearing clothing that protected the skin from the sun1, 5, 9, 17 (n=172) | 18.8%§ | 26.4% | F=2.54 | 0.11 |

| Percent of days wearing a hat with a wide brim1, 5, 7, 11, 15, 16 (n=183) | 12.0%§ | 13.0% | F=0.11 | 0.74 |

| Percent of days wearing sunglasses1, 10, 15 (n=192) | 62.5%§ | 65.4% | F=0.43 | 0.51 |

| Percent of days keeping time in the sun to a minimum1, 5, 7, 17 (n=180) | 49.3%§ | 60.4% | F=4.19 | 0.04 |

| Percent of days staying in the shade1, 5, 9, 15, 17 (n=170) | 40.2%§ | 40.2% | F=0.00 | 0.99 |

| Mean percent of days using all sun protection practices1, 5, 7, 17 (n=202) | 33.8%§ | 39.4% | F=4.07 | 0.04 |

Use was defined as running Solar Cell and receiving the feedback screen at least once.

Actual means

Least square means

Covariates controlled in the models:

Baseline value;

Age;

Education;

Race/Ethnicity;

Gender;

Skin score (Phenotypic Index);

Skin cancer;

Household head;

Household size;

Housing type;

Income;

Marital status;

MSA status;

Ownership status of living quarters;

Kids under 18;

Employment status; and

Do you agree or disagree that I look healthier and better when I tan?

Solar Cell when used had favorable effects on sun protection in some subgroups, specifically those defined by employment, household size, and gender. Participants not employed reported more days wearing wide-brim hats when using Solar Cell than those not using it (F=8.57, p<0.01; eTable 1); individuals who worked displayed little difference. In large households, participants using Solar Cell reported staying in the shade when outdoors on more days than those not using it (F=5.81, p<0.01; eTable 1). Also, using Solar Cell was associated with reporting spending fewer hours outdoors in the midday sun (between 10 am and 4 pm) by females; there was no difference in men (F=4.88, p=0.03; eTable 1).

Effect of Solar Cell on Theoretical Mediators

The main effect of Solar Cell on theoretical mediators – injunctive and descriptive norms, self-efficacy and outcome expectations, and intentions – was not statistically significant between treatment and control groups (eTable 2). However, two demographic characteristics moderated the effect of Solar Cell on injunctive norms and self-efficacy expectations. Participants living in non-metro areas assigned to Solar Cell reported lower injunctive norms for sun protection by family and friends than controls (F=5.98, p=0.01; Table 3). Lower income individuals assigned to Solar Cell were more confident they could practice sun safety than controls (F=3.53, p=0.01; higher income participants assigned to Solar Cell were less confident; Table 3).

Discussion

The Solar Cell mobile app appeared to promote sun protection practices, especially when it was used. Specifically, it increased use of shade. Shade can substantially reduce exposure to solar ultraviolet radiation (UVR),25 it needs to be available for it to be used. By contrast, Solar Cell reduced the use of sunscreen, which is not altogether unfavorable. Sunscreen, while a popular practice,23 is frequently not used properly to maximize its protective value.26 Many adults under apply it and/or fail to reapply it to receive its full protective value.27 Thus, health authorities recommend sunscreen be used as a secondary practice after staying indoors or in the shade and wearing protective clothing, hats and eyewear.28 Still, a recent SMS text messaging intervention did increase sunscreen use by middle school students.29

Solar Cell may be more effective with some groups than others. Women in the United States seem to practice more sun protection than men, and they may have been more responsive to Solar Cell's advice.23 The positive impact on individuals who preferred a suntan is a positive outcome, for tanning preferences may make them spend a large amount of time in the sun. When used, Solar Cell also benefited non-working participants and those in larger households by increasing use of wide brimmed hats, an uncommon precaution,23 and shade. Non-working participants may have more time to use and learn Solar Cell's advice than working individuals. Participants in larger households probably had more children; they may have followed Solar Cell's advice either over concern for their children's safety or to set a good example. It was somewhat unexpected that more affluent individuals who used Solar Cell had lower self-efficacy expectations than those who did not use it. Perhaps, more affluent adults were over-confident and Solar Cell showed them that sun protection was more complicated than they believed, which could make them try harder to take proper precautions.

It is disappointing that Solar Cell did not reduce sunburns, although neither did a recent text messaging intervention with adolescents.29 A recent meta-analysis showed variation in success of mobile interventions employing text messaging with those focused on smoking cessation and physical activity most successful.30 The lack of impact on sunburn prevalence may have occurred because use of Solar Cell was lower than expected, despite extensive usability testing, clear expectation that enrollees use it, and advice adults indicated they desired (e.g., estimates of the risk of sunburn)..18 Intervention attrition and declining and/or low use has been observed with other technology-based interventions (e.g., web-based interventions31-34) and with mobile interventions,35-39 despite the apparent enthusiasm for health-related mobile apps. . Unfortunately, commercial data indicates that most people who download apps fail to use them regularly.40 In our formative research,18 some individuals predicted that they would use the mobile app to learn sun protection and then discontinue use, a trend observed with a diabetes self-management mobile app.41 Some participants also may have tried Solar Cell and felt they already knew its advice. Increased use of Solar Cell was associated with improvements in sun protection practices and less time spent in the midday sun, so, future research on implementation strategies for mobile interventions is an important consideration both in randomized trials and when evidence-based interventions are translated more broadly.42-44

Fortunately, there was no evidence that providing advice on sunburn risk on a mobile app adjusted in real time for UV level and sun protection actions caused adults to spend more time outdoors and increase their high-risk UVR exposure. This unfavorable side effect has been observed with sunscreen45 and personal UV meters.46 However, Solar Cell, when used, appeared to motivate participants to try intentionally to reduce their time in the sun. The advice in Solar Cell was designed to help individuals make more informed decisions regarding sun exposure and sun protection by not only displaying the risk of sunburn but also advocating sun protection practices appropriate for the real-time UVR level and showing how taking these precautions decreased risk of sunburn, also in real time. The combination of tailored sun protection and real-time personal exposure information provided by the mobile app may be one way to avoid this undesirable side effect of sun protection technologies.47 Consistent with this conclusion, feedback on UVR exposure provided online to students and teachers in a primary school in Australia resulted in lower sun exposure of students.48

There were several strengths in the trial. The sample was large and recruited nationwide; randomization created equivalent groups; and few differences were associated with loss to follow-up, all implying that the evaluation was unbiased. However, there were notable shortcomings. Generalizability may be limited by the racial and education composition of the sample. The trial enrolled only non-Hispanic and Hispanic whites; however, the incidence of skin cancer is far higher among non-Hispanic whites than in other racial/ethnic groups and increasing in Hispanic whites.49,50 Likewise, the sample had high education, but smart phone ownership reflects this trend. Outcome measures were assessed by self-report but we used validated, reliable measures. The measures of sun protection practices and time spent outdoors were newly validated19 and used for one of the first times in a trial. As discussed above, the inability to get most intervention group participants to use Solar Cell was a major weakness. GfK would not provide us direct contact with participants. It was difficult to assist them with technical problems and we were only able to remind participants to download and use the mobile app one time after randomization.

Smart phone mobile apps have potential to deliver disease prevention interventions to a large and growing segment of the U.S. population, engage them proactively, confidentially, and repeatedly, and provide real-time personalized advice when and where they need it. Solar Cell, one of the first sun safety mobile apps evaluated in a randomized trial, may help adults with high risk skin types or who spend a lot of time outdoors make effective prevention decisions that reduce dangerous doses of UVR.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Mr. Craig Long at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration for his help in obtaining the daily UV Index forecast data.

Funding/Support: The research reported in this paper was supported by a contract from the National Cancer Institute (HHSN261201100108C).

| Funding/Sponsor was involved? | |

| Design and conduct of the study | No |

| Collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data | No |

| Preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript | No |

| Decision to submit the manuscript for publication | No |

Footnotes

Author Contribution: Dr. Buller and Ms. Liu had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: D. Buller, Berwick, Lantz, M. Buller, Kane, and Liu.

Acquisition of data: D. Buller, Kane, and Shane.

Analysis and interpretation of data: D. Buller, Berwick, Lantz, M. Buller, Kane, and Liu.

Drafting of the manuscript: D. Buller, Kane, and Liu.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: D. Buller, Berwick, Lantz, M. Buller, Kane, Shane, and Liu.

Statistical analysis: Buller, Berwick, and Liu.

Obtaining funding: D. Buller, Berwick, Lantz, and M. Buller.

Administrative, technical, or material support: D. Buller, Berwick Lantz, M. Buller, Kane, Shane, and Liu.

Study supervision: D. Buller, Kane, and Shane.

Financial Disclosure: Mary Buller is owner of Klein Buendel, Inc. Ms. Buller is David Buller's spouse. Ms. Buller and Dr. Buller receive a salary from Klein Buendel, Inc.

No other conflicts of interest are reported.

Reference List

- 1.Abroms L, Padmanabhan P, Evans W. Mobile phones for health communication to promote behavior change. In: Noar S, Harrington N, editors. E-Health Applications: Promising Strategies for Behavior Change. 1 ed. New York, NY: Routledge; 2012. pp. 147–166. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fox S. Health topics. [Accessed June 20, 2014];Pew Internet & American Life Project Web site. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2011/HealthTopics.aspx. Updated February 1, 2011.

- 3.Zickuhr K. Generations and their gadgets. [Accessed May 8, 2014];Pew Internet & American Life Project Web site. http://www.pewinternet.org/∼/media//Files/Reports/2011/PIP_Generations_and_Gadgets.pdf. Updated February 3, 2011.

- 4.Fox S. The social life of health information, 2011. [Accessed June 20, 2014];Pew Internet & American Life Project Web site. http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2009/8-The-Social-Life-of-Health-Information.aspx. Updated May 12, 2011.

- 5.Riley W, Rivera D, Atienza A, Nilsen W, Allison S, Mermelstein R. Health behavior models in the age of mobile interventions: are our theories up to the task? Trans Behav Med. 2011;1(1):53–71. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0021-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coomes CM, Lewis MA, Uhrig JD, Furberg RD, Harris JL, Bann CM. Beyond reminders: a conceptual framework for using short message service to promote prevention and improve healthcare quality and clinical outcomes for people living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2012;24(3):348–357. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.608421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fjeldsoe B, Miller Y, Marshall A. Text messaging interventions for chronic disease management and health promotion. In: Noar S, Harrington N, editors. E-Health Applications: Promising Strategies for Behavior Change. 1st ed. New York, NY: Routledge; 2012. pp. 167–186. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suffoletto B, Callaway C, Kristan J, Kraemer K, Clark DB. Text-message-based drinking assessments and brief interventions for young adults discharged from the emergency department. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36(3):552–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parrott R. Motivation to attend to health messages: presentation of content and linguistic considerations. In: Maibach E, Parrott R, editors. Designing Health Messages: Approaches From Communication Theory and Public Health Practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1995. pp. 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heron KE, Smyth JM. Ecological momentary interventions: incorporating mobile technology into psychosocial and health behaviour treatments. Br J Health Psychol. 2010;15(Pt 1):1–39. doi: 10.1348/135910709X466063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Westmaas JL, Bontemps-Jones J, Bauer JE. Social support in smoking cessation: reconciling theory and evidence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(7):695–707. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linsalata D, Slawsby A. Addressing Growing Handset Complexity With Software Solutions. Framingham, MA: IDC Analyze the Future; 2005. Aug, Report No.: IDCUS05WP002070. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: a Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janz NK, Champion VL, Strecher VJ. The health belief model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice. 3 ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts & Figures 2014. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bickers DR, Lim HW, Margolis D, et al. The burden of skin diseases: 2004 a joint project of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Society for Investigative Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(3):490–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ekwueme DU, Guy GP, Jr, Li C, Rim SH, Parelkar P, Chen SC. The health burden and economic costs of cutaneous melanoma mortality by race/ethnicity-United States, 2000 to 2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5 Suppl 1):S133–S143. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buller D, Berwick M, Shane J, Kane I, Lantz K, Buller M. User-centered development of a smart phone mobile application delivering personalized real-time advice on sun protection. Trans Behav Med. 2013;3(3):326–334. doi: 10.1007/s13142-013-0208-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hillhouse J, Turrisi R, Jaccard J, Robinson J. Accuracy of self-reported sun exposure and sun protection behavior. Prevention Science. 2012;13(5):519–531. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0278-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shoveller JA, Lovato CY. Measuring self-reported sunburn: challenges and recommendations. Chronic Dis Can. 2001;22(3-4):83–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanetsky PA, Rebbeck TR, Hummer AJ, et al. Population-based study of natural variation in the melanocortin-1 receptor gene and melanoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66(18):9330–9337. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banerjee SC, Greene K, Bagdasarov Z, Campo S. ‘My friends love to tan’: examining sensation seeking and the mediating role of association with friends who use tanning beds on tanning bed use intentions. Health Educ Res. 2009;24(6):989–998. doi: 10.1093/her/cyp035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buller D, Cokkinides V, Hall H, et al. Prevalence of sunburn, sun protection, and indoor tanning behaviors among Americans: systematic review from national surveys. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5 Suppl 1):114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gies P, Mackay C. Measurements of the solar UVR protection provided by shade structures in New Zealand primary schools. Photochem Photobiol. 2004;80(2):334–339. doi: 10.1562/2004-04-13-RA-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buller DB, Andersen PA, Walkosz BJ, et al. Compliance with sunscreen advice in a survey of adults engaged in outdoor winter recreation at high-elevation ski areas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(1):63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diffey BL. When should sunscreen be reapplied? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45(6):882–885. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.117385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization Ultraviolet radiation and the INTERSUN programme: Sun protection. [Accessed January 29, 2014];Simple precautions in the sun. http://www.who.int/uv/sun_protection/en/

- 29.Hingle MD, Snyder AL, McKenzie NE, et al. Effects of a short messaging service-based skin cancer prevention campaign in adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.06.014. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Head KJ, Noar SM, Iannarino NT, Grant Harrington N. Efficacy of text messaging-based interventions for health promotion: a meta-analysis. Social Science & Medicine. 2013;97:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leslie E, Marshall AL, Owen N, Bauman A. Engagement and retention of participants in a physical activity website. Prev Med. 2005;40(1):54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eysenbach G. The law of attrition. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7(1):e11. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7.1.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glasgow RE, Nelson CC, Kearney KA, et al. Reach, engagement, and retention in an Internet-based weight loss program in a multi-site randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9(2) doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.2.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buller DB, Floyd AHL. Internet-based interventions for health behavior change. In: Noar SM, Harrington NG, editors. EHealth Applications: Promising Strategies for Behavior Change. 1 ed. New York, NY: Routledge; 2012. pp. 59–78. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buller D, Borland R, Bettinghaus E, Shane JH, Zimmerman MA. Randomized trial of a smartphone mobile application compared to text messaging to support smoking cessation. Telemedicine and eHealth. 2014;20(3):206–214. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steinberg DM, Levine EL, Askew S, Foley P, Bennett GG. Daily text messaging for weight control among racial and ethnic minority women: randomized controlled pilot study. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(11):e244. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hashemian TS, Kritz-Silverstein D, Baker R. Text2Floss: the feasibility and acceptability of a text messaging intervention to improve oral health behavior and knowledge. Journal of public health dentistry. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jphd.12068. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Becker S, Miron-Shatz T, Schumacher N, Krocza J, Diamantidis C, Albrecht UV. mHealth 2.0: experiences, possibilities, and perspectives. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2014;2(2):e24. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen DK, Nardone B, Cotton M, West DP, Kundu RV. Use of a mobile application to characterize a remote and global population of acne patients and to disseminate peer-reviewed acne-related health education. JAMA Dermatology. 2014;150(6):660–662. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.9524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Localytics Localytics app stickiness index: Q2 2014. [Accessed September 2, 2014];Localytics Web site. http://www.localytics.com/resources/app-stickiness-index-q2-2014/. Updated 2014.

- 41.Tatara N, Arsand E, Skrovseth SO, Hartvigsen G. Long-term engagement with a mobile self-management system for people with type 2 diabetes. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2013;1(1):e1. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fixsen DL, Blase KA, Naoom SF, Wallace F. Core implementation components. Res Soc Work Pract. 2009;19(5):531–540. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Belig AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, Hecht J, Minicucci DS, Ory M. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: best practices and recommendations from the NIH behavior change consortium. Healthy Psychology. 2004;23:443–451. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rabin BA, Glasgow RE, Kerner JF, Klump MP, Brownson RC. Dissemination and implementation research on community-based cancer prevention: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4):443–456. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Autier P, Boniol M, Dore JF. Sunscreen use and increased duration of intentional sun exposure: still a burning issue. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(1):1–5. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carli P, Crocetti E, Chiarugi A, et al. The use of commercially available personal UV meters does cause less safe tanning habits: a randomized controlled trial. Photochem Photobiol. 2008;84(3):758–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Autier P. Sunscreen abuse for intentional sun exposure. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(s3):40–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kimlin M, Parisi A. Usage of real-time ultraviolet radiation data to modify the daily erythemal exposure of primary schoolchildren. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2001;17(3):130–135. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0781.2001.170305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu XC, Eide MJ, King J, et al. Racial and ethnic variations in incidence and survival of cutaneous melanoma in the United States, 1999-2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5 Suppl 1):S26–S37. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cockburn MG, Zadnick J, Deapen D. Developing epidemic of melanoma in the Hispanic population of California. Cancer. 2006;106(5):1162–1168. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.