Abstract

OBJECTIVES

The cognitive characteristics of individuals with Severe Compulsive Hoarding behaviors (SCH) are not well understood and existing studies have largely focused on individuals with SCH and concurrent anxiety disorders. The present study was conducted to evaluate the frequency with which SCH co-occurs with LLD and to compare the cognitive characteristics of individuals with late life depression and concurrent SCH (LLD+SCH) to that of LLD individuals without SCH (LLD).

METHODS

Participants included 52 LLD individuals who received psychiatric and neuropsychological evaluations as part of a larger study. Cognitive performance on measures of memory, attention, language, information processing speed, and categorization/problem solving ability was evaluated for each participant using standard neuropsychological measures. Measures of depression and anxiety symptom severity were also obtained.

RESULTS

Seven (13%) of the 52 LLD participants reported significant SCH behaviors. The two groups (LLD+SCH; LLD) did not differ with respect to demographic characteristics or severity of depression or anxiety. Individuals with LLD+SCH demonstrated significantly poorer performance on two measures of categorization/problem solving ability relative to individuals with isolated LLD. Clinically significant impairments on measures of categorization ability, information processing speed, and verbal memory were more common for SCH+LLD than LLD participants.

CONCLUSIONS

Our preliminary results suggest that SCH behaviors in LLD are associated with specific aspects of executive dysfunction characterized by categorization deficits and to a lesser extent information processing speed and verbal memory deficits. Further study of cognitive functioning in older adults with LLD and SCH may clarify the underlying cognitive characteristics of the SCH syndrome.

Keywords: Severe compulsive hoarding, late life depression, cognitive impairment, executive dysfunction, categorization, information processing speed, memory, attention

INTRODUCTION

While not currently identified as a psychiatric disorder, severe compulsive hoarding (SCH) is a behavioral syndrome typically defined as the excessive acquisition of and inability or unwillingness to discard seemingly useless items, causing significant distress or functional impairment, and resulting in living and/or work spaces that are unusable for their intended purposes (Steketee and Frost, 2003; Frost and Hartl, 1996; Saxena, 2007). Hoarding symptoms often begin between the ages of 10–13, although treatment-seeking for SCH is uncommon before age 40, and the incidence and recognition of SCH increases substantially among those over age 55 (Grisham et al., 2006; Mathews et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2001; Pertusa et al., 2008a; Best-Lavigniac, 2006; Frost and Gross, 1993b). Overall, the prevalence of SCH in the general population has been estimated at 4% (Samuels et al., 2008) and SCH is associated with a tremendous public health burden (Frost et al., 2000a; Tolin et al., 2008a). Specifically, SCH has been associated with an increased risk of morbidity and mortality, disability, home fires, eviction, and pest infestation and each year public service agencies expend tremendous time and financial resources on hoarding-related problems (Frost et al., 2000a; Tolin et al., 2008a; Snowdon et al., 2007; Best-Lavigniac, 2006; Kim et al., 2001; Frost et al., 1999). As examples, SCH has been identified as a direct contributor to up to 6% of deaths by house fire, 8–12% of compulsive hoarders have experienced or been threatened with eviction, and up to 3% have had a child or elder removed from the house due to safety concerns (Tolin et al., 2008b; Frost et al., 1999).

SCH is increasingly being conceptualized as a discrete clinical syndrome(Wu and Watson, 2005; Grisham et al., 2005) resulting from frontally-mediated cognitive dysfunction (Frost and Hartl, 1996; Hartl et al., 2005; Hartl et al., 2004; Grisham et al., 2007; Lawrence et al., 2006; Mataix-Cols et al., 2004; Luchian et al., 2007; Wincze et al., 2007; Steketee and Frost, 2003) and as such, identifying the cognitive characteristics of SCH represents a critical component of developing interventions to treat and/or prevent this debilitating syndrome. SCH behaviors most commonly occur in conjunction with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) (Steketee and Frost, 2003; Pertusa et al., 2008a; Saxena, 2007; Samuels et al., 2008; Samuels et al., 2007; Frost et al., 2000b; Frost et al., 1996) and, to date, most studies of cognitive functioning in SCH have been conducted among individuals with concurrent OCD. In these studies, SCH has been strongly linked to poorer performance on measures of categorization/ problem-solving ability and decision-making (Lawrence et al., 2006). Other studies have shown that OCD individuals with SCH behaviors had slower and more variable reaction times, increased impulsivity, and decreased sustained attention on visual attention tasks, as well as decreased spatial attention and short term visual memory, relative to both normal controls and a clinical sample comprised largely of individuals with anxiety disorders(Grisham et al., 2007). Deficits of visual learning, visual memory, and verbal memory have also been reported in a largely non-OCD SCH group relative to normal controls (Hartl et al., 2004).

Based on the existing literature it would appear that executive dysfunction, characterized primarily by categorization dysfunction, may be a central cognitive component of SCH. Additionally, this categorization dysfunction may either contribute to, or be influenced by, deficient sustained attention, slowed information processing speed, and memory impairments. The conceptualization of categorization deficits as a primary feature of SCH is supported by the fact that one of the most consistent cognitive symptoms reported by individuals with SCH is the inability to categorize objects, i.e., to identify the most salient characteristics of objects, and to group objects based on shared characteristics (Frost and Gross, 1993a; Wincze et al., 2007; Luchian et al., 2007). Additionally, recent findings suggest that SCH individuals often report greater distress associated with categorization tasks and take longer to completing these tasks than do non-hoarders, particularly when the items to be sorted have personal relevance (Wincze et al., 2007; Luchian et al., 2007).

Despite the emerging literature suggesting that categorization deficits may be a central cognitive component of SCH, at present very little is known about the cognitive characteristics of SCH in non-OCD individuals. Such studies would represent a significant avenue to further clarify the cognitive characteristics of SCH, particularly given several recent studies suggest that SCH does occur in the absence of other obsessive-compulsive symptoms (Pertusa et al., 2008b; Wincze et al., 2007). The study of cognitive functioning in individuals with SCH and concurrent late life depression (LLD) may hold particular promise to clarify the cognitive characteristics of SCH in non-OCD populations for several reasons. First, there is emerging evidence to suggest that depression is very common among individuals with SCH (Frost et al., 2009; Timpano et al., 2009; Winsberg et al., 1999), particularly in older adults (Ayers et al., 2009; Grisham et al., 2008; Saxena et al., 2007). Second, LLD is prevalent in the general population with recent estimates indicating that up to 14% of the general elderly population experience depressive symptoms meeting criteria for Major Depressive Disorder(Anstey et al., 2007) and the comorbidity of OCD in this patient population is relatively low(Mulsant et al., 1996). Third, mild cognitive impairments, and in particular frontally mediated deficits of executive functioning, are common in LLD (Butters et al., 2004; Kohler et al.; Butters et al., 2000). Further, it is well known that LLD is often a concurrent aspect or prodrome of several neurodegenerative disorders of late life that cause cognitive impairments and which are also associated with SCH(Nakaaki et al., 2007; Schweitzer et al., 2002; Lopez et al., 1995; Marx and Cohen-Mansfield, 2003). However, to our knowledge, there have been no studies conducted to date that have specifically evaluated the co-occurrence of SCH in LLD, or studies which have evaluated the cognitive characteristics of individuals with SCH and concurrent LLD in comparison to depressed individuals without SCH behaviors.

The current study was conducted to generate preliminary data on the co-occurrence of SCH with LLD as well as the cognitive characteristics of individuals with LLD and concurrent SCH in comparison to individuals with isolated LLD. We hypothesized that SCH would be more common in LLD than in the general population and that LLD individuals with SCH behaviors would exhibit poorer performance on measures of executive functioning that require visual categorization ability, both with respect to overall performance and the time to complete these tasks, relative to LLD individuals without SCH.

METHODS

Participants

Participants included 52 older adults who completed a neuropsychological evaluation as part of a larger study investigating cognitive functioning in LLD. In total, 123 participants were recruited for study participation through media advertisements. Seventy-one participants were excluded from participation in the study because they did not meet DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder (n=52), had a prior diagnosis of dementia or MMSE score of <25 at the initial screening evaluation (n=2), were taking anti-depressant medications (n=4), reported psychotic symptoms or had a past diagnosis of psychotic disorder or other Axis I disorder including OCD (n=8), had acute medical illness (n=1), had a history of significant head trauma (n=1), were not fluent in English (n=1), or if they had sensory limitations that precluded participation in neuropsychological testing (n=2). The remaining 52 participants were enrolled in the study and all participants provided informed consent to participate in the study. All study procedures were approved by a committee for human research institutional review board and participants were financially compensated for their time.

Measures

Measures of cognitive functioning and severity of symptoms of depression and anxiety were obtained for each participant during a single assessment period. The specific measures utilized and outcome variables for each of these measures are described below. Unless specified otherwise the normative data utilized for each cognitive test were obtained from the test manual. Additionally, demographic information (age, years of education) and onset of depression (early, late) was obtained for each participant. Late onset depression was designated for individuals with onset of their first major depressive episode after the age of 55 and early onset depression was designated for individuals with a history of depressive episodes at, or before, the age of 55.

AUDITORY MEMORY

Hopkins Verbal Learning Test - Revised (HVLT-R) (Brandt and Benedict, 2001)

The HVLT-R is a measure of memory for lists of verbally presented information. The two outcome variables utilized for this test were age-corrected scaled scores for the total number of correct responses on the learning and delayed free recall trials.

VISUAL MEMORY

Brief Visuospatial Memory Test - Revised (BVMT-R) (Benedict, 1997)

The BVMT-R is a measure of visual memory. The outcome variables utilized were age-corrected scaled scores for the number of total correct responses on the learning trials and the delayed free recall trial.

VISUOSPATIAL FUNCTIONING

Judgment of Line Orientation (JLO)(Benton, 1994)

The JLO is a motor free measure of visuospatial discrimination ability. The outcome variable utilized was a scaled score based on the total correct responses referenced to an age matched sample(Steinberg BA, 2005b).

Motor Free Visual Perception Test, Third Edition (MVPT-3)(Colarusso, 2005)

The MVPT is a motor free test of visual perception ability. The outcome variable utilized for this test was an age-corrected scaled score based on the total number of correct responses.

ATTENTION/WORKING MEMORY

Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third Edition Letter Number Sequencing (LNS) subtest(Wechsler, 1997)

The LNS subtest is a measure of auditory working memory, sequencing ability, and cognitive set shifting ability. The outcome variable utilized for this subtest was an age-corrected scaled score based on the total number of correct responses.

Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third Edition Digit Span subtest (Wechsler, 1997)

This test assesses auditory working memory and focused attention. The outcome variable utilized for this subtest was an age-corrected scaled score based on the total number of correct responses provided.

INFORMATION PROCESSING SPEED

Symbol Digit Modalities Test- Oral version (SDMT)(Smith, 2002)

The oral version of the SDMT is a motor free measure of information processing speed and visual working memory. The outcome variable utilized for this measure was an age- and education-corrected scaled score for the total number of correct responses.

The Stroop Color and Word Test (SCWT)(Golden and Freshwater, 2002)

The SCWT is a commonly utilized instrument of response inhibition, ability to maintain cognitive set, and information processing speed. The total number of correct responses on the color word trial was utilized as the outcome variable for this test with scaled scores based on age and education matched normative data(Steinberg BA, 2005a).

LANGUAGE/VERBAL ABSTRACT REASONING

Wechsler Adult Intelligence Test-Third Edition Similarities subtest(Wechsler, 1997)

The similarities subtest is a measure of abstract verbal reasoning ability. The primary outcome variable for this measure was an age-corrected scaled score calculated based on the total number of correct responses.

The Boston Naming Test (BNT)(Kaplan et al., 1983)

The BNT is a commonly utilized measure of confrontation naming ability. The short form(Lansing et al., 1999) of this test was utilized with age- and education-corrected scaled scores based on the total number of correct responses(Steinberg BA, 2005b) as the outcome variable.

CATEGORIZATION/PROBLEM SOLVING

The Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) Card Sorting Test(Delis et al., 2001)

The Card Sorting subtest of the D-KEFS is a measure of categorization of visual-spatial features, concept formation, cognitive flexibility, and problem solving skills. The two outcomes measures utilized were an age-corrected scaled score for the total number of correct responses and the average time to complete the first two card sort trials (seconds).

SEVERITY OF SYMPTOMS OF DEPRESSION AND ANXIETY

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale(Hamilton, 1960)

The Hamilton Depression Rating scale (HDRS) is a 24-item instrument utilized to assess severity of depressive symptoms. Scores range from 0 to 75; high scores indicate greater severity of depression.

Beck Anxiety Inventory(Beck and Steer, 1988)

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) is a 21 item scale utilized to assess symptoms of anxiety. Scores for each item range from 0 to 3 with a total score of 63; high scores indicated greater severity of anxiety.

ESTIMATED INTELLIGENCE

The National Adult Reading Test (NART)(Nelson and Willison, 1991)

The NART is a clinically validated measure utilized to estimate the premorbid intelligence of individuals suspected of cognitive decline. The outcome variable utilized was the estimated Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale full scale IQ score based on the number of correct responses on this measure.

PROCEDURES STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Psychiatric diagnoses were made by licensed psychologists utilizing DSM-IV criteria(APA, 1994) based on information obtained from the structured clinical interview for Diagnosis of DSM disorders (SCID)(First, 1997). A designation of SCH was made for individuals who: 1) self reported that hoarding behaviors were a significant problem area that they would like to address in treatment, 2) that hoarding behaviors caused significant functional impairment, and 3) that hoarding of objects resulted in limitations on the use of their residence. All psychiatric diagnoses and designations of SCH were reviewed at a consensus conference comprised of psychologists, social workers, and a neuropsychologist. Measures of cognitive functioning were administered by trained research staff under the supervision of a licensed neuropsychologist. Cognitive impairment was defined as performance falling at or below the 10th percentile (SS<7) when referenced to the normative data previously specified for each measure.

Statistical analyses were conducted as follows. We first conducted Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances and established that demographic and clinical data in both groups had equal variances. Next, we conducted t-tests for independent samples to evaluate group differences (LLD, LLD+SCH) on the demographic and clinical variables (age, education, depression and anxiety severity, and estimated premorbid intelligence) and a Pearson’s chi-square test to evaluate for gender differences between the two groups. We then conducted t-tests for independent samples to compare the two groups on measures of cognitive functioning on primary outcome variables. We subsequently conducted Pearson’s chi-square test to evaluate if the two groups differed with respect to the proportion of cognitive impairment demonstrated for each cognitive test. Because this work was exploratory we did not correct for multiple comparisons. A significance level of p < .05 was utilized for each statistical comparison.

RESULTS

Participants included 34 females (65%) and 18 males. The mean age of participants was 70.6 (SD= 7.0) and the mean level of education was 16.2 years (SD= 2.6). The ethnic distribution of the sample was made up of Caucasian (73%), African American (10%), Asian (10%), American Indian (5%), and Pacific Islander (2%) individuals. The mean Hamilton depression rating score for the sample was 22.8 (SD=2.7), twenty participants (38%) reported experiencing late onset depression, and the mean score on the Beck Anxiety Inventory was 18.0 (SD=12.0). The mean estimated full scale IQ score for the sample was 116.4 (SD=6.5). Seven individuals (13%) diagnosed with LLD reported significant SCH behaviors.

The two groups (LLD+SCH; LLD) did not differ with respect to age, education, gender, estimated full scale IQ score, onset of depression, or anxiety and depression severity (Table 1). On measures of neuropsychological functioning, LLD+SCH individuals showed poorer performance than LLD individuals in categorization ability/visual problem solving as assessed by the D-KEFS card sorting test for both the total number of correct responses t= −2.23, df = 45, p = .03 and the average time (seconds) to complete the sorting trials t = 2.77, df = 44, p = .01. There were no significant group differences demonstrated on the remaining measures of neuropsychological function.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Neuropsychological Functioning for Late Life Depression (LLD) Participants with/without Severe Compulsive Hoarding (SCH) Behaviors

| LLD (n=45) | LLD with SCH (n=7) | Statistical Test | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 70.2 (6.5) | 72.9 (9.9) | t (1,50)= 0.92 | .36 |

| Education | 16.2 (2.5) | 15.6 (3.1) | t (1,50)= −0.66 | .53 |

| Gender (male) | 16 (36%) | 2 (29%) | χ2 (1) = 0.13 | .79 |

| Hamilton Depression Rating Scale | 22.8 (2.7) | 23.4 (2.8) | t (1,50)= 0.61 | .55 |

| Onset of Depression (Late) | 3 (42.9%) | 17 (37.7%) | χ2 (1) = 0.6 | .81 |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory | 17.2 (11.1) | 23.1 (17.0) | t (1,49)= 1.23 | .23 |

| Estimated Full Scale IQ score | 116.5 (6.2) | 115.3 (8.1) | t (1,50)= 0.48 | .63 |

| AUDITORY MEMORY | ||||

| HVLT Learning Trials | 7.9 (3.6) | 7.1 (2.6) | t (1,50)= −0.54 | .59 |

| HVLT Delayed Recall | 8.1 (4.0) | 7.0 (3.3) | t (1,50)= −0.72 | .47 |

| VISUAL MEMORY | ||||

| BVMT-R Learning Trials | 7.6 (4.5) | 7.0 (5.6) | t (1,50)= −0.35 | .73 |

| BVMT-R Delayed Recall | 8.2 (4.7) | 8.3 (4.7) | t (1,50)= 0.05 | .96 |

| VISUAL SPATIAL PROCESSING | ||||

| Motor Free Visual Perception Test | 9.9 (4.3) | 7.4 (4.0) | t (1, 50)= −1.41 | .16 |

| Judgment of Line Orientation | 11.5 (2.9) | 10.0 (4.0) | t (1, 50)= −1.20 | .24 |

| LANGUAGE/ VERBAL REASONING | ||||

| WAIS III Similarities | 11.8 (4.2) | 11.2 (1.7) | t (1,50)= −0.36 | .72 |

| Boston Naming Test | 9.8 (4.8) | 8.6 (4.0) | t (1,50)= −0.63 | .53 |

| ATTENTION/WORKING MEMORY | ||||

| WAIS III Digit Span Test | 11.0 (3.0) | 9.2 (1.8) | t (1,45)= −1.44 | .16 |

| WAIS III Letter Number Sequencing | 10.2 (3.4) | 8.4 (4.6) | t (1,50)= −1.21 | .23 |

| INFORMATION PROCESSING SPEED | ||||

| Symbol Digit Modalities Test | 7.8 (2.9) | 6.2 (3.3) | t (1,50)= −1.30 | .20 |

| Stroop Color Word Test | 8.7 (3.2) | 7.0 (1.9) | t (1,49)= −1.33 | .19 |

| CATEGORIZATION / PROBLEM SOLVING | ||||

| DKEFS Card Sort Total Correct | 9.5 (2.9) | 6.7 (2.8) | t (1,45)= −2.23 | .03 |

| DKEFS Card Sort Time (seconds) | 23.4 (20.3) | 52.2 (31.0) | t (1,44)= 2.77 | .01 |

HVLT= Hopkins Verbal Learning Test; BVMT-R = Brief Visual Memory Test Revised; WAIS= Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale; DKEFS=Delis Kaplan Executive Function System

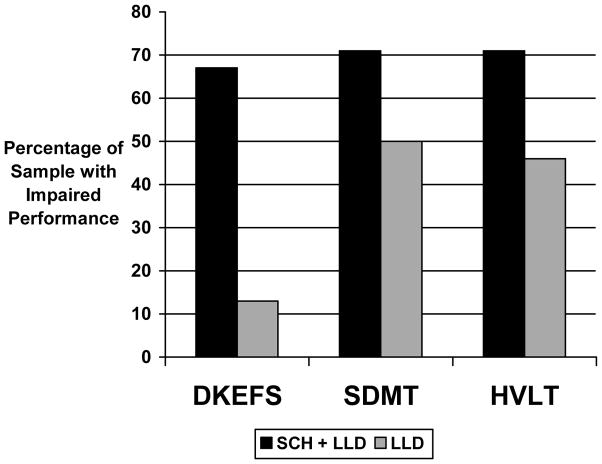

When cognitive impairment was examined as a categorical variable (i.e. percentage of individuals falling at or below the 10th percentile for each measure) a significantly greater proportion of the LLD+SCH group demonstrated impairment relative to LLD participants on the measures of categorization ability (D-KEFS card sorting task; 67% vs 13%; χ2 = 8.18, df=1, p=.003), information processing speed (SDMT; 71% vs 50%; χ2 = 3.71, df=1, p=.05), and verbal memory (HVLT delayed recall; 71% vs 46%; χ2 = 4.05, df=1, p=.04). The frequency of cognitive impairments on each of the remaining neuropsychological measures did not differ between the two groups.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to examine the relationship between SCH and frontally-mediated cognitive function among individuals with LLD. Although not our primary aim, we were also able to examine two clinically relevant features of SCH -- the frequency to which SCH co-occurs with LLD, and the relationship between SCH and measures of anxiety and depression. Our results suggest that SCH behaviors are common among individuals with LLD, as over 10% of LLD participants in our treatment study also reported significant SCH behaviors that were consistent with previously established definitions for this behavioral syndrome(Frost and Hartl, 1996). The frequency at which SCH co-occurred with LLD in our sample was significantly higher than estimates of the prevalence of SCH in the general population 4% (Samuels et al., 2008). Further, our results indicate that the LLD+SCH group did not differ from the LLD group with respect to depression severity, age of depression onset, or anxiety symptom severity, with the latter finding being relatively unexpected given other findings that suggest that SCH individuals often report significant distress related to anxious symptomatology(Timpano et al., 2009).

In our view, our most significant findings were that when compared to individuals with isolated LLD, individuals with LLD+SCH demonstrated both significantly poorer functioning on measures of categorization ability and an increased incidence of clinically significant cognitive impairment on categorization tasks (67% vs 13%). Together, these findings provide compelling support for the conceptualization of SCH as being a frontally mediated behavioral syndrome characterized by underlying executive dysfunction. Our findings are consistent with the extant literature suggesting that categorization tasks are particularly difficult for individuals with SCH (Frost and Gross, 1993a; Wincze et al., 2007; Luchian et al., 2007) as well as previous findings documenting similar deficiencies in individuals with SCH and concurrent OCD in younger adults(Lawrence et al., 2006).

While performance discrepancies on measures of attention, information processing speed, memory, and visuospatial processing between our two sample groups did not reach statistical significance, individuals with LLD+SCH did perform more poorly in each of these cognitive domains relative to our LLD comparison group as might be expected from the extant literature (Grisham et al., 2007; Hartl et al., 2004). Further, a greater proportion of individuals with LLD+SCH demonstrated clinically significant impairments on measures of information processing speed and verbal memory than the LLD group. Collectively, these results suggest that further study of cognitive functioning in these domains is warranted in larger studies of SCH in LLD to determine the degree to which cognitive inefficiencies in these domains may be caused by, or contribute to, categorization deficits. Additionally, our results also suggest that evaluating the incidence of specific types of cognitive impairments may be a more useful way to characterize the cognitive characteristics of SCH in LLD than raw score comparisons.

There are several significant limitations to our study that should be discussed in relation to our findings. First, and perhaps most significant, our study was based on a clinical sample of convenience, and as such the sample size of individuals with LLD+SCH was quite small. As a result, we may not have had the statistical power to demonstrate cognitive performance decrements in other cognitive domains for LLD+SCH individuals and our positive findings may have been heavily influenced by the performance of a few individuals in our LLD+SCH sample. Additionally, we did not utilize a structured rating scale to classify the severity of SCH behaviors in our sample. Although we employed patient reports of SCH behaviors that caused significant distress and functional impairment as our criteria for SCH, we did not rate the severity of these behaviors with instruments typically utilized for this purpose such as the Saving Inventory-Revised(Frost et al., 2004). Such an approach would have enabled us to more clearly identify the cognitive correlates of SCH behaviors. Further, we did not obtain information regarding the age of onset of SCH behaviors and as such are not able to comment on the degree to which these behaviors were chronic, or if the onset coincided with symptoms of LLD. While some recent studies have found that a late onset of hoarding behaviors is relatively uncommon(Ayers et al., 2009), numerous other studies have implicated the manifestation of SCH behaviors in later life related to neurodegenerative disease(Nakaaki et al., 2007; Marx and Cohen-Mansfield, 2003; Mendez and Shapira, 2008), suggesting that SCH may arise as a result of varied etiologies. These findings may partially explain the increased prevalence of this disorder in older adults (Grisham et al., 2006; Mathews et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2001; Pertusa et al., 2008a; Best-Lavigniac, 2006) but also indicate that age of onset of SCH behaviors may be an important area of future study with regard to the cognitive characteristics of SCH.

As all participants in this study were thoroughly evaluated in a diagnostic assessment, we can report that these SCH behaviors were not associated with current diagnoses of OCD in this study. However, we did not utilize a normal control group in our analyses by design, as all individuals with SCH in our study had a concurrent diagnosis of LLD we felt that a comparison to normal control participants would not have been useful in identifying differences in cognitive functioning associated with SCH in this sample. In future studies, however, utilizing additional comparison groups of individuals with SCH in the absence of LLD and non-psychiatric control participants will be valuable in further identifying the cognitive correlates of SCH. Other limitations of the study include our inability to evaluate the degree to which LLD+SCH individuals differed from LLD individuals with respect to performance on sustained visual attention tasks, areas of documented inefficiency in other clinical populations of SCH (Hartl et al., 2004), as we did not employ continuous performance tasks in the larger study. Further, we were unable to evaluate the degree to which categorization tasks caused distress among our two patient groups which would have also been an interesting comparison in this patient population.

CONCLUSIONS

We believe our results offer compelling preliminary data to suggest that SCH is common in older adults with LLD and that SCH in this population is primarily associated with executive dysfunction characterized by categorization deficits. Continued study of cognitive functioning in SCH represents a critical step in determining the underlying neurobiological etiology of this debilitating syndrome, which in turn could influence the development of new treatments to prevent or minimize the impact of SCH.

FIGURE 1.

Proportion of Participants with Clinically Significant Impairments on Neuropsychological Measures for Late Life Depression Participants with/without Severe Compulsive Hoarding (SCH) Behaviors (n=52)

HVLT= Hopkins Verbal Learning Test Delayed Recall; SDMT = Symbol Digit Modalities Test; DKEFS=Delis Kaplan Executive Function System Card Sort

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIMH Grants K08 MH081065, K24 MH074717, R01 MH63982, and R24 MH077192. The information in this manuscript and the manuscript itself are new and original and have never been published either electronically or in print. There are no financial or other relationships that could be interpreted as a conflict of interest affecting this manuscript. We would like to acknowledge Erin Gillung, Claudine Catledge, Nicole Duffy, and Eamonn McKay for their work with participant recruitment and data management for this project.

Footnotes

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: This research was supported by NIMH Grants K08 MH081065, K24 MH074717, R01 MH63982, and R24 MH077192

References

- Anstey KJ, von Sanden C, Sargent-Cox K, Luszcz MA. Prevalence and risk factors for depression in a longitudinal, population-based study including individuals in the community and residential care. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:497–505. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31802e21d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. American Psychiatric Association; Washington DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ayers CR, Saxena S, Golshan S, Wetherell JL. Age at onset and clinical features of late life compulsive hoarding. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009 doi: 10.1002/gps.2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Steer RA. Beck Anxiety Inventory. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict RH. Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; Lutz: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Benton AL. Judgement of Line Orientation. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; Lutz: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Best-Lavigniac J. Hoarding as an adult: overview and implications for practice. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2006;44:48–51. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20060101-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt J, Benedict RHB. Hopkins Verbal Learning Test - Revised. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; Lutz, FL: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Butters MA, Becker JT, Nebes RD, Zmuda MD, Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, Reynolds CF., 3rd Changes in cognitive functioning following treatment of late-life depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1949–54. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.12.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butters MA, Whyte EM, Nebes RD, Begley AE, Dew MA, Mulsant BH, Zmuda MD, Bhalla R, Meltzer CC, Pollock BG, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Becker JT. The nature and determinants of neuropsychological functioning in late-life depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:587–95. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.6.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colarusso RP, Hammill DD. Motor-Free Visual Perception Test. Academic Therapy Publications; Novato: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Kaplan E, Kramer JH, Ober BA. Delis-Kaplan Executive Function Scale (D-KEFS) The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I), Clinician Version. American Psychiatric Publishing; Arlington, VA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Frost R, Gross RC. The hoarding of possessions. Behav Res Ther. 1993a;31:367–81. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(93)90094-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Gross RC. The hoarding of possessions. Behav Res Ther. 1993b;31:367–81. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(93)90094-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Hartl TL. A cognitive-behavioral model of compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther. 1996;34:341–50. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Krause MS, Steketee G. Hoarding and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Behav Modif. 1996;20:116–32. doi: 10.1177/01454455960201006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Steketee G, Grisham J. Measurement of compulsive hoarding: saving inventory-revised. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42:1163–82. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Steketee G, Williams L. Hoarding: a community health problem. Health Soc Care Community. 2000a;8:229–234. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2000.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Steketee G, Williams LF, Warren R. Mood, personality disorder symptoms and disability in obsessive compulsive hoarders: a comparison with clinical and nonclinical controls. Behav Res Ther. 2000b;38:1071–81. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Steketee G, Youngren VR, Mallya GK. The threat of the housing inspector: a case of hoarding. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1999;6:270–8. doi: 10.3109/10673229909000339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Tolin DF, Steketee G, Fitch KE, Selbo-Bruns A. Excessive acquisition in hoarding. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23:632–9. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden C, Freshwater SM. Stroop Color and Word Test. Stoelting: Wood Dale; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Grisham JR, Brown TA, Liverant GI, Campbell-Sills L. The distinctiveness of compulsive hoarding from obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2005;19:767–79. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisham JR, Brown TA, Savage CR, Steketee G, Barlow DH. Neuropsychological impairment associated with compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:1471–83. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisham JR, Frost RO, Steketee G, Kim HJ, Hood S. Age of onset of compulsive hoarding. J Anxiety Disord. 2006;20:675–86. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisham JR, Steketee G, Frost RO. Interpersonal problems and emotional intelligence in compulsive hoarding. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:E63–71. doi: 10.1002/da.20327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl TL, Duffany SR, Allen GJ, Steketee G, Frost RO. Relationships among compulsive hoarding, trauma, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:269–76. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl TL, Frost RO, Allen GJ, Deckersbach T, Steketee G, Duffany SR, Savage CR. Actual and perceived memory deficits in individuals with compulsive hoarding. Depress Anxiety. 2004;20:59–69. doi: 10.1002/da.20010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. Boston Naming Test (Revised) Lea & Febiger; Philadelphia: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Steketee G, Frost RO. Hoarding by elderly people. Health Soc Work. 2001;26:176–84. doi: 10.1093/hsw/26.3.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler S, Thomas AJ, Barnett NA, O'Brien JT. The pattern and course of cognitive impairment in late-life depression. Psychol Med. 40:591–602. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansing AE, Ivnik RJ, Cullum CM, Randolph C. An empirically derived short form of the Boston naming test. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1999;14:481–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence NS, Wooderson S, Mataix-Cols D, David R, Speckens A, Phillips ML. Decision making and set shifting impairments are associated with distinct symptom dimensions in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuropsychology. 2006;20:409–19. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.20.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez OL, Gonzalez MP, Becker JT, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Sudilovsky A, DeKosky ST. Symptoms of depression in Alzheimer's disease, frontal lobe-type dementia, and subcortical dementia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;769:389–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb38153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchian SA, McNally RJ, Hooley JM. Cognitive aspects of nonclinical obsessive-compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:1657–62. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx MS, Cohen-Mansfield J. Hoarding behavior in the elderly: a comparison between community-dwelling persons and nursing home residents. Int Psychogeriatr. 2003;15:289–306. doi: 10.1017/s1041610203009542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mataix-Cols D, Wooderson S, Lawrence N, Brammer MJ, Speckens A, Phillips ML. Distinct neural correlates of washing, checking, and hoarding symptom dimensions in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:564–76. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.6.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews CA, Nievergelt CM, Azzam A, Garrido H, Chavira DA, Wessel J, Bagnarello M, Reus VI, Schork NJ. Heritability and clinical features of multigenerational families with obsessive-compulsive disorder and hoarding. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144:174–82. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez MF, Shapira JS. The spectrum of recurrent thoughts and behaviors in frontotemporal dementia. CNS Spectr. 2008;13:202–8. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900028443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulsant BH, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Shear MK, Sweet RA, Miller M. Comorbid anxiety disorders in late-life depression. Anxiety. 1996;2:242–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-7154(1996)2:5<242::AID-ANXI6>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaaki S, Murata Y, Sato J, Shinagawa Y, Hongo J, Tatsumi H, Mimura M, Furukawa TA. Impairment of decision-making cognition in a case of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) presenting with pathologic gambling and hoarding as the initial symptoms. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2007;20:121–5. doi: 10.1097/WNN.0b013e31804c6ff7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson H, Willison J. National Adult Reading Test (NART) nferNelson Publishing Company Ltd; London: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Pertusa A, Fullana MA, Singh S, Alonso P, Menchon JM, Mataix-Cols D. Compulsive Hoarding: OCD Symptom, Distinct Clinical Syndrome, or Both? Am J Psychiatry. 2008a doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07111730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertusa A, Fullana MA, Singh S, Alonso P, Menchon JM, Mataix-Cols D. Compulsive hoarding: OCD symptom, distinct clinical syndrome, or both? Am J Psychiatry. 2008b;165:1289–98. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07111730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels JF, Bienvenu OJ, 3rd, Pinto A, Fyer AJ, McCracken JT, Rauch SL, Murphy DL, Grados MA, Greenberg BD, Knowles JA, Piacentini J, Cannistraro PA, Cullen B, Riddle MA, Rasmussen SA, Pauls DL, Willour VL, Shugart YY, Liang KY, Hoehn-Saric R, Nestadt G. Hoarding in obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from the OCD Collaborative Genetics Study. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:673–86. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels JF, Bienvenu OJ, Grados MA, Cullen B, Riddle MA, Liang KY, Eaton WW, Nestadt G. Prevalence and correlates of hoarding behavior in a community-based sample. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46:836–44. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S. Is compulsive hoarding a genetically and neurobiologically discrete syndrome? Implications for diagnostic classification. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:380–4. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.3.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S, Brody AL, Maidment KM, Baxter LR., Jr Paroxetine treatment of compulsive hoarding. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:481–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer I, Tuckwell V, O'Brien J, Ames D. Is late onset depression a prodrome to dementia? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17:997–1005. doi: 10.1002/gps.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. Symbol Digit Modalities Test. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Snowdon J, Shah A, Halliday G. Severe domestic squalor: a review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2007;19:37–51. doi: 10.1017/S1041610206004236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg BA, BL, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ. Mayo's Older American Normative Studies: Age-and IQ-Adjusted Norms for the Trail Making Test, The Stroop Test, and MAE Controlled Oral Word Association Test. Clin Neuropsychol. 2005a;19:329–77. doi: 10.1080/13854040590945210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg BA, BL, Smith GE, Langellotti C, Ivnik RJ. Mayo's Older Americans Normative Studies: Age- and IQ-Adjusted Norms for the Boston Naming Test, The MAE Token Test, and the Judgment of Line Orientation Test. Clin Neuropsychol. 2005b;19:280–328. doi: 10.1080/13854040590945229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steketee G, Frost R. Compulsive hoarding: current status of the research. Clin Psychol Rev. 2003;23:905–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timpano KR, Buckner JD, Richey JA, Murphy DL, Schmidt NB. Exploration of anxiety sensitivity and distress tolerance as vulnerability factors for hoarding behaviors. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26:343–53. doi: 10.1002/da.20469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G, Fitch KE. Family burden of compulsive hoarding: results of an internet survey. Behav Res Ther. 2008a;46:334–44. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G, Gray KD, Fitch KE. The economic and social burden of compulsive hoarding. Psychiatry Res. 2008b;160:200–11. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale- Third Edition, Administration and Scoring Manual. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wincze JP, Steketee G, Frost RO. Categorization in compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winsberg ME, Cassic KS, Koran LM. Hoarding in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a report of 20 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:591–7. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n0905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu KD, Watson D. Hoarding and its relation to obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:897–921. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]