Abstract

A multiplex real-time PCR (quantitative PCR [qPCR]) assay detecting herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) DNA together with an internal control was developed on the BD Max platform combining automated DNA extraction and an open amplification procedure. Its performance was compared to those of PCR assays routinely used in the laboratory, namely, a laboratory-developed test for HSV DNA on the LightCycler instrument and a test using a commercial master mix for VZV DNA on the ABI7500fast system. Using a pool of negative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples spiked with either calibrated controls for HSV-1 and VZV or dilutions of a clinical strain that was previously quantified for HSV-2, the empirical limit of detection of the BD Max assay was 195.65, 91.80, and 414.07 copies/ml for HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV, respectively. All the samples from HSV and VZV DNA quality control panels (Quality Control for Molecular Diagnostics [QCMD], 2013, Glasgow, United Kingdom) were correctly identified by the BD Max assay. From 180 clinical specimens of various origins, 2 CSF samples were found invalid by the BD Max assay due to the absence of detection of the internal control; a concordance of 100% was observed between the BD Max assay and the corresponding routine tests. The BD Max assay detected the PCR signal 3 to 4 cycles earlier than did the routine methods. With results available within 2 h on a wide range of specimens, this sensitive and fully automated PCR assay exhibited the qualities required for detecting simultaneously HSV and VZV DNA on a routine basis.

INTRODUCTION

Herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and -2, respectively) and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) are human double-stranded DNA viruses belonging to the Herpesviridae family. In immunocompetent hosts, benign vesicular eruption of the skin and mucosa occurs during either the primary infection or reactivation episodes (1). However, life-threatening manifestations, mainly related to virus neurovirulence, can be observed (2), HSV-1 and VZV being the first and second most common causes of viral encephalitis, respectively (3, 4). These viruses are associated with mortality and morbidity, especially when treatment with acyclovir is delayed (5). HSV-2 is more likely responsible for meningitis (1). HSV-2 and VZV are also implicated in neonatal infections (1, 6, 7).

Due to similarities in the clinical presentations of the diseases caused by these 3 herpesviruses and other pathogens, virological testing is often needed. Accurate and specific diagnosis is of special importance in cases of severe infection or in infection occurring in immunosuppressed patients who can present atypical clinical pictures (8). In replacement of cell culture and immune detection of viral antigens, molecular assays are currently the main tool used for the virological diagnosis of infections related to HSV and VZV. This trend is due to the multiple advantages of nucleic acid testing (NAT), including the rapid availability of results, its adaptation to a wide diversity of clinical specimens, the capacity for automation, and, mostly, its high sensitivity and specificity. Several FDA-approved or CE-marked in vitro diagnostic (IVD) kits are available for detecting these viruses in various specimens (9–11). However, all of them propose separate detection for HSV and VZV DNA, and only a few multiplex assays including both agents have been published as laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) (10, 12).

Although detection of viral DNA is the gold standard for the virological diagnosis of neurological severe infections (3), to date, no commercial fully automated PCR assay detecting both HSV and VZV is available. However, an FDA-approved assay for HSV detection in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was recently validated for clinical use (13, 14). As low viral loads (<500 copies/ml) are not infrequent in CSF of patients suffering encephalitis associated with HSV (15–20), it was recommended to reach a sensitivity of at least 200 copies/ml for the detection of this agent in CSF (21). The same need for sensitive tests is found with encephalitis associated with VZV (15, 22).

The recently commercialized BD Max system (Becton Dickinson, Pont-de-Claix, France) combines the extraction and amplification steps on the same instrument, shortening the hands-on time and allowing its use in emergency molecular diagnostic testing. Dedicated analyte kits (23–26) but also master mix from other companies (27) and laboratory-developed methods (28) can be used on this open, fully automated platform. Recently, the BD Max system was used to perform in 2 separate assays a real-time PCR test detecting HSV and VZV in skin and mucosal lesions (29).

The present work was aimed at developing on the BD Max instrument a laboratory-developed HSV/VZV PCR assay able to detect HSV and VZV DNA in the same reaction tube. The sensitivity of the BD Max assay was shown to be similar to that of PCR assays routinely used in the laboratory on various types of clinical specimens, including CSF.

(The data were previously presented at the 30th Clinical Virology Symposium [April 2014, Daytona Beach, FL].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Positive controls used for sensitivity determination.

Commercially available quantified standards of HSV-1 and VZV claimed to contain 10,000 copies/ml of each target (Qnostics, Glasgow, United Kingdom) were used to check the empirical sensitivity of the new assay. Given that the HSV-2 control was not convenient due to the fact that the strain sequence is not referenced in GenBank, a clinical strain of HSV-2 was chosen as a positive control. For the three controls, serial dilutions were performed in a pool of CSF samples that tested negative for HSV and VZV before DNA extraction. Their viral load, expressed as copies per milliliter, was measured using the HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV R-gene kit (bioMérieux SA, Verniolles, France) (30).

QCMD panels.

The 2013 HSV and VZV panels of the Quality Control for Molecular Diagnostics organization (QCMD; Glasgow, United Kingdom) were tested retrospectively. Each panel contained 9 presumably positive specimens and 1 negative specimen.

Clinical specimens.

For clinical validation, 180 specimens of various origins were retrospectively analyzed by the routine and BD Max assays, including 38 CSF samples. All were residual specimens previously analyzed in the laboratory for diagnosis of HSV or VZV infection and stored at −20°C. This research was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki declaration of the rights of patients.

Primers and probes.

For HSV, both the routine and BD Max assays targeted the viral DNA polymerase gene and were able to detect HSV-1 and HSV-2 without type differentiation, as previously described (31). For VZV, the BD Max assay targeted the viral DNA polymerase gene (32) whereas the routine assay targeted glycoprotein 19 (11). For the BD Max multiplex assay, primers targeting the sample process control (SPC) were added to the PCR master mix; this internal control consists of a fragment of Drosophila melanogaster genome (GenBank sequence accession no. AC246436; nucleotides 35779 to 35978) cloned in a pUC119 derivative (GenBank sequence accession no. U07650.1). The sequences of primers and probes used for the BD Max multiplex assay are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of primers and probes used in this study for BD Max multiplex assaya

| Target | Length of product (bp) | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Tm, °C (% CG) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSV | 92 | Forward: CATCACCGACCCGGAGAGGGAC | 66.9 (68) |

| Reverse: GGGCCAGGCGCTTGTTGGTGTA | 69.0 (63) | ||

| Probe: FAM-CCGCCGAACTGAGCAGACACCCGCGC-BHQ1 | 79.8 (73) | ||

| VZV | 63 | Forward: CGGCATGGCCCGTCTAT | 56 (64.7) |

| Reverse: TCGCGTGCTGCGGC | 50 (78.6) | ||

| Probe: YY-ATTCAGCAATGGAAACACACGACGCC-BHQ1 | 54.4 (50) | ||

| SPC | 149 | Forward: GGATCTAGCCGTGTGCCCGCT | 66.8 (66) |

| Reverse: GGCATGGAGGTTGTCCCATTTGTG | 64.5 (54) | ||

| Probe: ATTO647n-TTGATGCCTCTTCACATTGCTCCACCTTTCCT-BHQ3 | 67.8 (45) |

Abbreviations: HSV, herpes simplex virus; VZV, varicella-zoster virus; YY, Yakima Yellow; SPC, sample process control; BHQ, black hole quencher; FAM, 6-carboxyfluorescein; Tm, melting temperature; ATTO, German company that manufactures the corresponding fluorophore.

Routine assay for detection of HSV genome.

The extraction step was performed on 200 μl of sample using the NucliSens easyMAG instrument with the Specific B protocol, as recommended by the manufacturer (bioMérieux SA, Marcy l'Etoile, France). For CSF specimens, 100 μl of Basematrix diluent (InGen, Chilly-Mazarin, France) was added during the lysis step in order to increase the extraction efficiency, as previously recommended (33). The elution volume was 50 μl. Five microliters of extract was mixed with 10 pmol of each HSV primer, 4 pmol of the HSV probe (Table 1), and the LightCycler FastStart DNA Master HybProbe (Roche, Meylan, France) in a glass capillary. The cycling conditions on LightCycler 1.0 were as previously published (31); a total of 55 cycles was performed, and every positive signal was interpreted as positive without a threshold cycle (CT) cutoff value. No internal control was present for this assay.

Routine assay for detection of VZV genome.

The extraction conditions are similar to those described above for the HSV routine assay. Ten microliters of extract was added to 15 μl of ready-to-use VZV R-gene master mix before cycling on an ABI7500fast system (Applied Biosystems) as recommended by bioMérieux. An internal control was included through extraction with the sample.

BD Max assay.

The PCR master mix consisted of 10 pmol of each primer and 4 pmol of the probe for HSV and VZV and 8 pmol of each primer and 4 pmol of the probe for the SPC (Table 1), in a final volume of 7.5 μl containing the RealTime Ready DNA Probe Master (Roche) for one test. This mixture of reagents, considered a batch, was prealiquoted in BD Max snap-in tubes, sealed using colored cover foil with the Axygen PlateMax semiautomated plate sealer (Axygen Scientific, Union City, CA, USA; 1 time for 8 s at 180°C), and stored at −20°C until use. It was shown to be stable for at least 12 weeks (data not shown), which allows testing of the positive and negative controls at the beginning and end of each batch use, without intermediate controls for each run.

The BD Max HSV/VZV/SPC multiplex assay was fully automated. A 200-μl volume of sample, together with 550 μl of DNA-free water, was added to the sample buffer tube. A snap-in tube containing the master mix was thawed and snapped into the BD Max ExK DNA-1 reagent strip containing all the materials (pipette tips and waste) and reagents (wash buffer and elution buffer) necessary for the DNA extraction step, as well as the SPC template that was coextracted and coamplified with the viral targets for controlling the full process. After the sample buffer tube and the strip were placed on the BD Max instrument, the automated method was started. The sample lysis was performed onboard at 62°C for 9 min. The cycling conditions consisted of denaturation for 60 s at 98°C followed by 55 cycles of 5.7 s at 98°C and 33.3 s at 62°C. The results were available within 1.5 h for fewer than 5 samples; 6 to 9 min was necessary for testing each series of 4 additional samples. Up to 24 specimens can be tested in the same run for a total time of 130 min.

The CT cutoff value of SPC that was used for considering a sample to be invalid was 29.6, which corresponds to the mean of the SPC of the 87 negative clinical specimens plus 2 standard deviations, in accordance with a previous study (34).

Statistical analysis.

The limit of detection (LoD) of the assays was estimated by PriProbit analysis (version 1.63) (35). The LoD of the assay corresponded to the value of viral DNA load detected with 95% probability and the estimation of its 95% confidence interval (95% CI). The Spearman coefficient was used for correlation analyses.

RESULTS

Reproducibility of BD Max assay.

Five replicates of each serial dilution of positive controls for HSV-1, HSV-2, or VZV were tested to evaluate the intra- and interassay reproducibility of the multiplex BD Max assay (Table 2). Reproducibility of the CT value for the SPC was also satisfactory with a coefficient of variation (CV) of <5% (data not shown). No cross-contamination was observed when alternating highly positive and negative samples in the same run (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Reproducibility of BD Max assay for known copy numbers of HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV DNA diluted in a pool of HSV- and VZV-negative CSF specimensa

| Viral load (copies/ml) | Interrun |

Intrarun |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of positive replicates | Mean CT ± SD (% coefficient of variation) | No. of positive replicates | Mean CT ± SD (% coefficient of variation) | |

| HSV-1 | ||||

| 3,333 | 5 | 35.66 ± 0.62 (1.74) | 5 | 35.08 ± 0.85 (2.42) |

| 1,111 | 5 | 37.88 ± 0.96 (2.53) | 5 | 38.76 ± 1.05 (2.72) |

| 370 | 5 | 42.00 ± 2.26 (5.39) | 5 | 43.64 ± 1.72 (3.94) |

| HSV-2 | ||||

| 39,800 | 5 | 30.16 ± 1.39 (4.60) | 5 | 29.66 ± 0.56 (1.89) |

| 3,980 | 5 | 33.64 ± 1.19 (3.53) | 5 | 32.38 ± 0.37 (1.14) |

| 398 | 4 | 36.38 ± 0.90 (2.47) | 4 | 35.58 ± 0.54 (1.51) |

| VZV | ||||

| 3,333 | 5 | 31.42 ± 0.68 (2.15) | 5 | 31.32 ± 0.58 (1.85) |

| 1,111 | 5 | 33.24 ± 0.95 (2.86) | 5 | 32.98 ± 0.71 (2.15) |

| 370 | 5 | 36.70 ± 1.78 (4.84) | 5 | 38.98 ± 2.45 (6.28) |

Each sample was tested in five replicates.

Sensitivity of BD Max assay.

The empirical sensitivity of the BD Max assay was determined by using serial dilutions of positive controls from 10 independent determinations as described above. The LoD of the BD Max multiplex assay was 195.65 copies/ml (95% CI, 117.41, 828.07), 91.80 copies/ml (95% CI, 37.90, 1,499.20), and 414.07 copies/ml (95% CI, 234.80, 1,303.80) for HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV, respectively.

Validation of BD Max assay by using external quality controls.

The 20 specimens of the 2013 QCMD panels were tested by the routine and BD Max assays. As shown in Table 3, all of the specimens were reliably detected by both assays, including those exhibiting very low viral DNA loads (<500 copies/ml). Specimens expected to be negative for HSV or VZV DNA tested negative by both assays.

TABLE 3.

Detection of HSV and VZV DNA in specimens of 2013 QCMD panels using routine and multiplex BD Max assays

| QCMD specimen | Expected result from QCMD |

CT by assay |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Routine assayb |

BD Max assay |

|||||

| DNA content (origin) | Sample concn (copies/ml)a | HSV | VZV | HSV | VZV | |

| HSVDNA13-07 | HSV-1 (MacIntyre strain) | 9,840 | 34.82 | NTc | 30.24 | Negd |

| HSVDNA13-01 | HSV-1 (95/1906) | 9,795 | 34.96 | NT | 30.03 | Neg |

| HSVDNA13-08 | HSV-1 (95/1906) | 490 | 38.45 | NT | 34.72 | Neg |

| HSVDNA13-04 | HSV-1 (MacIntyre strain) | 189 | 40.19 | NT | 38.00 | Neg |

| HSVDNA13-02 | HSV-2 (MS) | 6,353 | 32.71 | NT | 29.06 | Neg |

| HSVDNA13-03 | HSV-2 (09-015681) | 4,335 | 32.36 | NT | 28.24 | Neg |

| HSVDNA13-05 | HSV-2 (MS) | 249 | 39.74 | NT | 33.97 | Neg |

| HSVDNA13-09 | HSV-2 (09-015681) | 91 | 44.46 | NT | 34.13 | Neg |

| HSVDNA13-10 | VZV | NAe | Neg | 29.30 | Neg | 28.69 |

| HSVDNA13-06 | Negative | Neg | NT | Neg | Neg | |

| VZVDNA13-04 | VZV (OKA) | 25,586 | NT | 29.11 | Neg | 28.66 |

| VZVDNA13-05 | VZV (63/1444) | 2,576 | NT | 33.47 | Neg | 30.91 |

| VZVDNA13-01 | VZV (Ellen strain) | 2,249 | NT | 33.56 | Neg | 31.32 |

| VZVDNA13-06 | VZV (OKA) | 1,140 | NT | 33.65 | Neg | 31.46 |

| VZVDNA13-07 | VZV (9/84) | 783 | NT | 34.91 | Neg | 32.00 |

| VZVDNA13-08 | VZV (63/1444) | 226 | NT | 37.14 | Neg | 34.64 |

| VZVDNA13-10 | VZV (Ellen strain) | 118 | NT | 37.76 | Neg | 34.84 |

| VZVDNA13-02 | VZV (9/84) | 61 | NT | 39.44 | Neg | 35.15 |

| VZVDNA13-03 | HSV-1 | 10,000 | 35.12 | Neg | 30.47 | Neg |

| VZVDNA13-09 | Negative | NT | Neg | Neg | Neg | |

As determined by QCMD.

The routine tests that were used as comparators were a laboratory-developed test for HSV DNA on LightCycler and a test using a commercial master mix for VZV DNA on ABI7500fast.

NT, not tested.

Neg, negative.

NA, not available.

Clinical validation of BD Max assay.

From the 180 tested clinical samples, no amplification of the SPC target was observed for 2 CSF samples (1.11% with comparison to the total number of samples and 7.14% with comparison to the number of CSF samples) using the BD Max HSV/VZV/SPC assay, suggesting the presence of PCR inhibitors; despite an additional cycle of freezing/thawing, the SPC target remained undetected. These 2 samples that displayed no atypical characteristics in terms of aspect or consistency were found negative for HSV and VZV by the routine assays, with a correct amplification of the internal control present in the VZV assay.

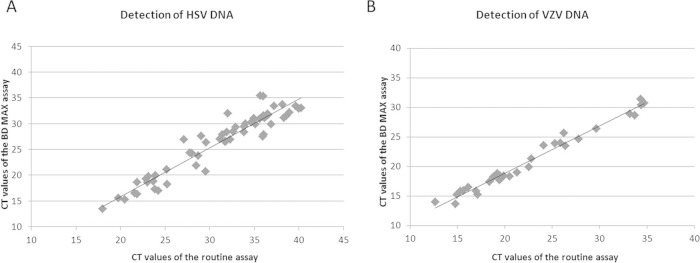

All of the remaining 178 specimens were found concordant by both assays for the two viruses, corresponding to a total agreement of 100% for both HSV and VZV (kappa coefficient of 1 with a 95% confidence interval of 0.974 to 1 for both targets). Table 4 depicts the distribution of the results obtained with different kinds of specimens using the multiplex BD Max assay. As shown in Fig. 1, the CT values of specimens found positive for HSV (n = 61 specimens) or VZV (n = 31 specimens) were highly correlated by comparing the BD Max and routine assays. Of note, the BD Max assay detected the PCR signal 3 to 4 cycles earlier than did the routine methods.

TABLE 4.

Clinical analysis of the 180 specimens tested in the study using multiplex HSV/VZV/SPC assay on BD Max platform

| Type of specimen | No. of specimens with result by BD Max assay: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSV positive | VZV positive | HSV and VZV positive | Negative | Invalid | |

| CSF | 9 | 1 | 0 | 26 | 2 |

| Neonatal swab | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 |

| Genital swab | 10 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Oral or nasal swab | 11 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| Cutaneous swab | 8 | 26 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Ocular swab | 1 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 |

| Respiratory secretion | 17 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 0 |

| Amniotic fluid | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| Serum | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

FIG 1.

Correlation of the CT values of the clinical specimens found positive by routine and multiplex BD Max HSV/VZV/SPC assays. (A) Specimens found positive for HSV (Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.91, P < 0.0001). (B) Specimens found positive for VZV (Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.98, P < 0.0001).

DISCUSSION

The laboratory-developed HSV/VZV/SPC BD Max assay presented here is a multiplex assay aimed at detecting both HSV and VZV DNA, allowing the use of only one test in routine settings for the clinical diagnosis of these 2 infectious agents in various clinical specimens, including CSF. Although not differentiating between HSV-1 and HSV-2, it was shown to be at least as sensitive as the molecular assays routinely used in the laboratory for separately detecting HSV and VZV DNA.

In addition to HSV and VZV targets, an internal control, named SPC, was incorporated into the new assay in order to prevent false-negative results. As SPC is included in the extraction strip, this DNA is extracted and amplified concomitantly with the viral targets, allowing the control of the full process on the BD Max platform. The presence of PCR inhibitors has been reported in several types of specimens, including whole blood, CSF, and amniotic fluid. Of note, this control is absent in the HSV test routinely used in the laboratory. As described with other HSV molecular assays (36–39), the prevalence of PCR inhibition was low in this study (1.1%) and concerned CSF specimens only. Approximately 7% of the tested CSF samples were found invalid; the test would need to be validated on a larger number of CSF samples for verifying whether this observation is anecdotal or corresponds to a recurrent phenomenon with this type of sample, which could be a limitation for the test. In the case of inhibition, the specimen should be retested after dilution or a freeze-thawing cycle.

The level of analytical sensitivity for detecting HSV and VZV DNA in CSF specimens is critical. The lack of sensitivity of most of the HSV DNA assays tested during an international external quality assessment performed more than 10 years ago conducted by Schloss et al. recommends that the analytical sensitivity of NAT for the diagnosis of HSV encephalitis should be close to 200 genome copies/ml (22). Several studies confirmed that the HSV DNA load can be low in CSF in the case of encephalitis (15–20). The VZV DNA load in CSF can also be low (15), especially in the case of VZV-associated vasculopathy (22), meningitis (40, 41), and encephalitis (21), leading to the recommendation of combining the titration of VZV antibodies in CSF with the direct detection of viral DNA (3, 42). Few of the assays published in the literature (10) have been tested for LoD estimation, and only one met the criterion of 200 copies/ml for HSV in CSF specimens (43); another one exhibited a correct sensitivity but was validated for cutaneous and mucous swabs only (44). Concerning the test described in the present report, the LoDs were shown to be less than 200 and 500 copies/ml for HSV and VZV, respectively. This high sensitivity was confirmed on the 2013 QCMD panels; it validates the use of the present assay for detecting simultaneously HSV and VZV DNA in CSF and in other specimens exhibiting low viral loads, such as peripheral blood specimens or swabs taken from late cutaneous or mucosal lesions (45).

A limit of the current assay is the lack of distinction between HSV-1 and HSV-2. Although HSV typing could be useful in certain clinical situations, notably in chronic infection occurring in immunosuppressed patients or in severe diseases such as encephalitis and neonatal infections (46–48), the therapeutic issue is not dependent upon the HSV serotype in most cases (49–51). Consequently, HSV typing can be performed in a further step by using specific primers able to distinguish between the two types (10).

The BD Max platform combines the extraction and amplification steps with reduced hands-on time and full automation. Moreover, the master mix can be prepared as a batch that is validated once before use and is stable for approximately 12 weeks, avoiding the daily use of controls in addition to the clinical specimen, thus reducing the cost. The result can be obtained in less than 2 h, allowing the use of this assay for rapid testing done by non-molecular diagnostic staff in case of emergency, especially for the etiological diagnosis of viral encephalitis. In the future, other targets could be implemented in the assay either by using the two remaining channels of detection or by introducing a second master mix in the new extraction strips available from BD, which could allow the additional detection of other neurotropic pathogens such as enteroviruses, Streptococcus pneumoniae, or Neisseria meningitidis.

In conclusion, this new test targeting HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV, together with an internal control (SPC), is the first multiplex laboratory-developed assay for the simultaneous detection of DNA of these viruses in various clinical specimens, including CSF, on the fully automated BD Max platform; due to its high sensitivity and reliability, it is suitable for implementation in emergency medicine laboratories.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Noémie Bossu, Lucie Dancert, and Margot Chasseur are acknowledged for technical assistance.

This study received the financial support of Becton Dickinson (protocol no. 1208034) without influence on its design and on the evaluation of results. S.P., P.O.V., and A.E. received travel grants from Becton Dickinson. The other two authors have no conflict of interest to declare in relation to the results of this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Steiner I, Kennedy PG, Pachner AR. 2007. The neurotropic herpes viruses: herpes simplex and varicella-zoster. Lancet Neurol 6:1015–1028. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70267-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rozenberg F, Deback C, Agut H. 2011. Herpes simplex encephalitis: from virus to therapy. Infect Disord Drug Targets 11:235–250. doi: 10.2174/187152611795768088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Venkatesan A, Tunkel AR, Bloch KC, Lauring AS, Sejvar J, Bitnun A, Stahl J-P, Mailles A, Drebot M, Rupprecht CE, Yoder J, Cope JR, Wilson MR, Whitley RJ, Sullivan J, Granerod J, Jones C, Eastwood K, Ward KN, Durrheim DN, Solbrig MV, Guo-Dong L, Glaser CA, International Encephalitis Consortium. 2013. Case definitions, diagnostic algorithms, and priorities in encephalitis: consensus statement of the International Encephalitis Consortium. Clin Infect Dis 57:1114–1128. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mailles A, Stahl J-P, Steering Committee and Investigators Group. 2009. Infectious encephalitis in France in 2007: a national prospective study. Clin Infect Dis 49:1838–1847. doi: 10.1086/648419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stahl JP, Mailles A, De Broucker T, Steering Committee and Investigators Group. 2012. Herpes simplex encephalitis and management of acyclovir in encephalitis patients in France. Epidemiol Infect 140:372–381. doi: 10.1017/S0950268811000483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corey L, Wald A. 2009. Maternal and neonatal herpes simplex virus infections. N Engl J Med 361:1376–1385. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0807633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith CK, Arvin AM. 2009. Varicella in the fetus and newborn. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 14:209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Styczynski J, Reusser P, Einsele H, de la Camara R, Cordonnier C, Ward KN, Ljungman P, Engelhard D, Second European Conference on Infections in Leukemia. 2009. Management of HSV, VZV and EBV infections in patients with hematological malignancies and after SCT: guidelines from the Second European Conference on Infections in Leukemia. Bone Marrow Transplant 43:757–770. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson NW, Buchan BW, Ledeboer NA. 2014. Light microscopy, culture, molecular, and serologic methods for detection of herpes simplex virus. J Clin Microbiol 52:2–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01966-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan F, Day S, Lu X, Tang Y-W. 2014. Laboratory diagnosis of HSV and varicella zoster virus infections. Future Virol 9:721–731. doi: 10.2217/fvl.14.61. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fan F, Stiles J, Mikhlina A, Lu X, Babady NE, Tang Y-W. 2014. Clinical validation of the Lyra direct HSV 1+2/VZV assay for simultaneous detection and differentiation of three herpesviruses in cutaneous and mucocutaneous lesions. J Clin Microbiol 52:3799–3801. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02098-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stöcher M, Hölzl G, Stekel H, Berg J. 2004. Automated detection of five human herpes virus DNAs by a set of LightCycler PCRs complemented with a single multiple internal control. J Clin Virol 29:171–178. doi: 10.1016/S1386-6532(03)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gitman MR, Ferguson D, Landry ML. 2013. Comparison of Simplexa HSV 1 & 2 PCR with culture, immunofluorescence, and laboratory-developed TaqMan PCR for detection of herpes simplex virus in swab specimens. J Clin Microbiol 51:3765–3769. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01413-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Binnicker MJ, Espy MJ, Irish CL. 2014. Rapid and direct detection of herpes simplex virus in cerebrospinal fluid by use of a commercial real-time PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol 52:4361–4362. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02623-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aberle SW, Puchhammer-Stöckl E. 2002. Diagnosis of herpesvirus infections of the central nervous system. J Clin Virol 25(Suppl 1):S79–S85. doi: 10.1016/S1386-6532(02)00037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ziyaeyan M, Alborzi A, Borhani Haghighi A, Jamalidoust M, Moeini M, Pourabbas B. 2011. Diagnosis and quantitative detection of HSV DNA in samples from patients with suspected herpes simplex encephalitis. Braz J Infect Dis 15:211–214. doi: 10.1016/S1413-8670(11)70177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang JW, Lin M, Chiu L, Koay ESC. 2010. Viral loads of herpes simplex virus in clinical samples—a 5-year retrospective analysis. J Med Virol 82:1911–1916. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schloss L, Falk KI, Skoog E, Brytting M, Linde A, Aurelius E. 2009. Monitoring of herpes simplex virus DNA types 1 and 2 viral load in cerebrospinal fluid by real-time PCR in patients with herpes simplex encephalitis. J Med Virol 81:1432–1437. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poissy J, Champenois K, Dewilde A, Melliez H, Georges H, Senneville E, Yazdanpanah Y. 2012. Impact of herpes simplex virus load and red blood cells in cerebrospinal fluid upon herpes simplex meningo-encephalitis outcome. BMC Infect Dis 12:356. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy RF, Caliendo AM. 2009. Relative quantity of cerebrospinal fluid herpes simplex virus DNA in adult cases of encephalitis and meningitis. Am J Clin Pathol 132:687–690. doi: 10.1309/AJCP0KN1PCHEYSIK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schloss L, van Loon AM, Cinque P, Cleator G, Echevarria J-M, Falk KI, Klapper P, Schirm J, Vestergaard BF, Niesters H, Popow-Kraupp T, Quint W, Linde A. 2003. An international external quality assessment of nucleic acid amplification of herpes simplex virus. J Clin Virol 28:175–185. doi: 10.1016/S1386-6532(03)00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Persson A, Bergström T, Lindh M, Namvar L, Studahl M. 2009. Varicella-zoster virus CNS disease—viral load, clinical manifestations and sequels. J Clin Virol 46:249–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dalpke AH, Hofko M, Zimmermann S. 2012. Comparison of the BD Max methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) assay and the BD GeneOhm MRSA achromopeptidase assay with direct- and enriched-culture techniques using clinical specimens for detection of MRSA. J Clin Microbiol 50:3365–3367. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01496-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verhoeven PO, Carricajo A, Pillet S, Ros A, Fonsale N, Botelho-Nevers E, Lucht F, Berthelot P, Pozzetto B, Grattard F. 2013. Evaluation of the new CE-IVD marked BD MAX Cdiff assay for the detection of toxigenic Clostridium difficile harboring the tcdB gene from clinical stool samples. J Microbiol Methods 94:58–60. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riedlinger J, Beqaj SH, Milish MA, Young S, Smith R, Dodd M, Hankerd RE, Lebar WD, Newton DW. 2010. Multicenter evaluation of the BD Max GBS assay for detection of group B streptococci in prenatal vaginal and rectal screening swab specimens from pregnant women. J Clin Microbiol 48:4239–4241. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00947-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biswas JS, Al-Ali A, Rajput P, Smith D, Goldenberg SD. 2014. A parallel diagnostic accuracy study of three molecular panels for the detection of bacterial gastroenteritis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 33:2075–2081. doi: 10.1007/s10096-014-2177-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kenicer J, Hardie A, Hamilton F, Gadsby N, Templeton K. 2014. Comparative evaluation of the Diagenode multiplex PCR assay on the BD Max system versus a routine in-house assay for detection of Bordetella pertussis. J Clin Microbiol 52:2668–2670. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00212-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dalpke AH, Hofko M, Zimmermann S. 2013. Development and evaluation of a real-time PCR assay for detection of Pneumocystis jirovecii on the fully automated BD MAX platform. J Clin Microbiol 51:2337–2343. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00616-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cárdenas AM, Edelstein PH, Alby K. 2014. Development and optimization of a real-time PCR assay for detection of herpes simplex and varicella-zoster viruses in skin and mucosal lesions by use of the BD Max open system. J Clin Microbiol 52:4375–4376. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02237-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frobert E, Billaud G, Casalegno J-S, Eibach D, Goncalves D, Robert J-M, Lina B, Morfin F. 2013. The clinical interest of HSV1 semi-quantification in bronchoalveolar lavage. J Clin Virol 58:265–268. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kessler HH, Mühlbauer G, Rinner B, Stelzl E, Berger A, Dörr HW, Santner B, Marth E, Rabenau H. 2000. Detection of herpes simplex virus DNA by real-time PCR. J Clin Microbiol 38:2638–2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weidmann M, Armbruster K, Hufert FT. 2008. Challenges in designing a Taqman-based multiplex assay for the simultaneous detection of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 and varicella-zoster virus. J Clin Virol 42:326–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ginocchio CC, Zhang F, Malhotra A, Manji R, Sillekens P, Foolen H, Overdyk M, Peeters M. 2005. Development, technical performance, and clinical evaluation of a NucliSens basic kit application for detection of enterovirus RNA in cerebrospinal fluid. J Clin Microbiol 43:2616–2623. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2616-2623.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noordhoek GT, Weel JFL, Poelstra E, Hooghiemstra M, Brandenburg AH. 2008. Clinical validation of a new real-time PCR assay for detection of enteroviruses and parechoviruses, and implications for diagnostic procedures. J Clin Virol 41:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sakuma M. 1998. Probit analysis of preference data. Appl Entomol Zool 33:339–347. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mengelle C, Sandres-Sauné K, Miédougé M, Mansuy JM, Bouquies C, Izopet J. 2004. Use of two real-time polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) to detect herpes simplex type 1 and 2-DNA after automated extraction of nucleic acid. J Med Virol 74:459–462. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hodgson J, Zuckerman M, Smith M. 2007. Development of a novel internal control for a real-time PCR for HSV DNA types 1 and 2. J Clin Virol 38:217–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hobson-Peters J, O'Loughlin P, Toye P. 2007. Development of an internally controlled, homogeneous polymerase chain reaction assay for the simultaneous detection and discrimination of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 and varicella-zoster virus. Mol Cell Probes 21:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heaton PR, Espy MJ, Binnicker MJ. 2015. Evaluation of 2 multiplex real-time PCR assays for the detection of HSV-1/2 and varicella zoster virus directly from clinical samples. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 81:169–170. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aberle SW, Aberle JH, Steininger C, Puchhammer-Stöckl E. 2005. Quantitative real time PCR detection of varicella-zoster virus DNA in cerebrospinal fluid in patients with neurological disease. Med Microbiol Immunol (Berl) 194:7–12. doi: 10.1007/s00430-003-0202-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rottenstreich A, Oz ZK, Oren I. 2014. Association between viral load of varicella zoster virus in cerebrospinal fluid and the clinical course of central nervous system infection. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 79:174–177. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen JI. 2013. Herpes zoster. N Engl J Med 369:1766–1767. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1310369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Finnström N, Bergsten K, Ström H, Sundell T, Martin S, Wutzler P, Sauerbrei A. 2009. Analysis of varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus in various clinical samples by the use of different PCR assays. J Virol Methods 160:193–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2009.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rose L, Herra CM, Crowley B. 2008. Evaluation of real-time polymerase chain reaction assays for the detection of herpes simplex virus in swab specimens. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 27:857–861. doi: 10.1007/s10096-008-0502-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Magaret AS, Wald A, Huang M-L, Selke S, Corey L. 2007. Optimizing PCR positivity criterion for detection of herpes simplex virus DNA on skin and mucosa. J Clin Microbiol 45:1618–1620. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01405-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whitley RJ, Roizman B. 2001. Herpes simplex virus infections. Lancet 357:1513–1518. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04638-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.LeGoff J, Péré H, Bélec L. 2014. Diagnosis of genital herpes simplex virus infection in the clinical laboratory. Virol J 11:83. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-11-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fatahzadeh M, Schwartz RA. 2007. Human herpes simplex virus infections: epidemiology, pathogenesis, symptomatology, diagnosis, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol 57:737–763. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roizman B, Knipe DM, Whitley RJ. 2007. Herpes simplex viruses, p 2503–2601. In Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, Straus SE (ed), Fields virology, 5th ed, vol 2 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garland SM, Steben M. 2014. Genital herpes. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 28:1098–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2014.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Albrecht MA. 2014. Treatment of genital herpes simplex virus infection. In Post TW. (ed), UpToDate. UpToDate, Waltham, MA: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-genital-herpes-simplex-virus-infection. [Google Scholar]