Abstract

Data in the literature regarding the factors that predict unfavorable outcomes in adult herpetic meningoencephalitis (HME) cases are scarce. We conducted a multicenter study in order to provide insights into the predictors of HME outcomes, with special emphasis on the use and timing of antiviral treatment. Samples from 501 patients with molecular confirmation from cerebrospinal fluid were included from 35 referral centers in 10 countries. Four hundred thirty-eight patients were found to be eligible for the analysis. Overall, 232 (52.9%) patients experienced unfavorable outcomes, 44 died, and 188 survived, with sequelae. Age (odds ratio [OR], 1.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02 to 1.05), Glasgow Coma Scale score (OR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.77 to 0.93), and symptomatic periods of 2 to 7 days (OR, 1.80; 95% CI, 1.16 to 2.79) and >7 days (OR, 3.75; 95% CI, 1.72 to 8.15) until the commencement of treatment predicted unfavorable outcomes. The outcome in HME patients is related to a combination of therapeutic and host factors. This study suggests that rapid diagnosis and early administration of antiviral treatment in HME patients are keys to a favorable outcome.

INTRODUCTION

Encephalitis due to herpes simplex virus (HSV) is the most frequent form of sporadic fatal encephalitis in the world and accounts for 10 to 20% of all viral encephalitis cases worldwide (1–3). The annual incidence for herpetic meningoencephalitis (HME) is around 0.2 to 0.4 adults per 100,000 (4). In addition, patients with HME experience exceedingly high unfavorable outcomes, including death and long-term sequelae, despite treatment (5–8).

Previous studies (9, 10) have assessed outcomes, in particular by comparing the efficacies of herpetic antiviral drugs. To the best of our knowledge, data thoroughly assessing the predictors of unfavorable outcome in HME patients do not exist in the literature. One more potential limitation of the studies published was that they included cases without virological confirmation (11–13), thus blurring the inferences made. Hence, in this multinational study, we included only HME patients with a definite virological diagnosis. Consequently, our study makes use of data from the largest case series ever reported in the literature to determine the predictors of unfavorable outcome in HME.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

This retrospective multicenter study included hospitalized patients from referral centers in 10 countries (Croatia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Egypt, France, Iraq, Italy, Lebanon, Slovenia, and Turkey) between 2000 and 2013. Only adult patients (>15 years of age) with HME were included. No control groups were included for this study. The institutional review board of the Dr. Lütfi Kirdar Training and Research Hospital in Istanbul, Turkey, approved the study, which was exempt from the requirement for informed patient consent.

The inclusion criteria comprised both of the following: (i) positive cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-PCR result for herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1), HSV-2, or both in a patient with meningoencephalitis and (ii) the unlikely presence of any other infectious disease of the brain.

Definitions.

Meningoencephalitis was defined as a clinical, radiological, and/or laboratory presentation compatible with encephalitis (3, 8, 14) and meningitis (1, 15). The clinical findings related to encephalitis mainly included changes in consciousness and/or language, behavioral abnormalities, memory impairment, and seizures. The magnetic resonance imaging, electrophysiological studies, and/or CSF analysis data were used to provide clues regarding the encephalitic component of the disease (3). Meningitis was identified by the presence of an abnormal number of leukocytes in the CSF, along with compatible clinical findings, like fever, headache, meningism, cranial nerve palsies, or altered consciousness (16). Unfavorable outcome was defined as patients who died of HME or survived with sequelae. New-onset convulsion was defined as a convulsion observed between the onset of symptoms and the start of antiviral treatment for HME. Immunosuppression was defined as a patient who was under a long-term steroid treatment or had a disease(s) causing immunosuppression, such as malignancy, autoimmune disease, or diabetes. Motor symptoms were defined as locomotor deficiency, paresis, tetraparesis, hemiparesis, quadriparesis, quadriplegia, spasticity, left foot drop, or disrupted motoric skills.

Statistical analysis.

Statistics were done using the software package Stata 13.1 (StataCorp, TX, USA). In the univariate analysis, categorical variables were compared by Pearson's chi-square test and where applicable by Fisher's exact test. Continuous variables were compared by Student's t test or by the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, depending on the normality assumption for which the Shapiro-Wilk and Shapiro-Francia tests were used.

A total of 3% (15/438) of the observations were missing. The pattern of missingness indicated this as “missing completely at random.” Therefore, missing observations were not filled via a multiple imputation procedure.

A binary logistic regression model was constructed via a bootstrap resampling procedure described in detail elsewhere (17). Briefly, the data set was replaced by resampling 200 times during the logistic regression analysis of the full model, consisting of all potential variables. Eventually, variables with frequencies of >30% of the bootstrapped data sets with a 0.1 significance threshold were included in the final model. The final model was tested with logistic regression, including all possible interaction terms. Colinearity was also tested and eliminated.

RESULTS

In this study, data from 501 HME patients were submitted from 35 referral centers in 10 countries (Turkey [n = 144], Denmark [n = 127], France [n = 64], Slovenia [n = 54], Croatia [n = 32], Iraq [n = 30], the Czech Republic [n = 23], Italy [n = 12], Lebanon [n = 8], and Egypt [n = 7]). Sixty-three patients were excluded, due to either missing critical data or the absence of molecular confirmation, leaving 438 patients eligible for outcome analysis. HSV-1/2 PCR was found to be positive in 105 patients. HSV-1 DNA was positive in 300 cases, and HSV-2 DNA was positive in 79 cases. A brain biopsy was not performed in any of the patients. In this study, 375 (85.6%) patients received intravenous aciclovir, and in 53 (12.1%) cases, oral valaciclovir was given following intravenous aciclovir treatment. Nine cases were treated with valaciclovir. Finally, one case received intravenous ganciclovir following intravenous aciclovir. The mean ± standard deviation (SD) treatment duration of the aciclovir-only arm was 21.6 ± 12.3 days, while valaciclovir alone was given for a mean ± SD of 10.3 ± 4.6 days. In the group receiving intravenous aciclovir followed by oral valaciclovir, the drugs were given for 15.5 ± 10.7 and 32.7 ± 18.9 days, respectively. The mean ± SD dose of intravenous aciclovir was 36.7 ± 5.7 mg/kg of body weight/day. In this study, 232 (52.9%) patients experienced unfavorable outcomes. Forty-four HME patients died, and 188 survivors of the disease had experienced sequelae at the end of antiviral treatment. Overall, there were 313 disorders attributed to HME in 188 patients with sequelae. Memory disorder (n = 62), behavioral disorders (n = 55), speech impairment (n = 53), motor symptoms (n = 40), epilepsy (n = 34), cognitive impairment (n = 29), headache (n = 13), psychiatric disorders (n = 10), balance disorder (n = 6), and visual disturbances (n = 5) were the frequent unfavorable outcomes. Tinnitus, sleeping disorder, coma, autoimmune encephalitis, neurogenic bladder, and autonomy loss were seen in a single case each.

The baseline characteristics of the study group are presented in Table 1. Briefly, the study group consisted of patients with a mean (± SD) age of 50.6 (± 18.3) years, and 48.4% (212/438) were of the male gender. Almost half of the patients (44.5% [195/438]) received antiviral treatment during the first 2 days after the onset of symptoms. The median elapsed time between the onset of symptoms and antiviral treatment was 3 days (interquartile range [IQR], 1 to 5 days). In this study, 10% (44/438) died, while 42.9% (188/438) survived with severe sequelae. A univariate comparison of the variables between the patients with favorable and unfavorable outcomes is presented in Table 2. Age, male gender, longer time gap between the onset of symptoms and antiviral treatment, lower Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores, and convulsion were significantly different in the patients with unfavorable outcomes compared to those in the patients with favorable outcomes. Among these, however, only age, GCS score, and time to antiviral treatment were included in the final model (Table 3).

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Variable | Dataa |

|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) (yr) | 50.58 ± 18.27 |

| Gender | |

| Women | 226 (51.6) |

| Men | 212 (48.4) |

| Elapsed time between OS & AVT (days)b | |

| ≤2 | 195 (44.5) |

| >2 and ≤7 | 191 (43.6) |

| >7 | 47 (10.7) |

| Missing data | 5 (1.1) |

| Glasgow Coma Scale score (median [IQR]) | 14 (13–15) |

| New-onset convulsionc | |

| No | 343 (78.3) |

| Yes | 91 (20.8) |

| Missing data | 4 (0.9) |

| Immunosuppressiond | |

| No | 379 (86.5) |

| Yes | 59 (13.5) |

| Outcome | |

| Favorable | 206 (47.0) |

| Unfavorable | 232 (53.0) |

| Died | 44 (10.0) |

| Survived with severe sequela(e) | 188 (42.9) |

Values are no. (%) of patients, unless otherwise indicated. Total n = 438.

Elapsed time between onset of symptoms (OS) and the start of antiviral treatment (AVT).

Defined as a convulsion observed before therapy.

Defined as long-term steroid use or other immunosuppressive state.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of variables among patients with favorable and unfavorable outcomes

| Variable | Data for outcome ofa: |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Favorable | Unfavorable | ||

| Age (mean ± SD) (yr) | 44.50 ± 16.80 | 55.97 ± 17.86 | <0.001 |

| Gender | 0.005 | ||

| Women | 121 (58.7) | 105 (45.3) | |

| Men | 85 (41.3) | 127 (54.7) | |

| Elapsed time between OS & AVT (days)b | <0.001 | ||

| ≤2 | 113 (55.7) | 82 (35.7) | |

| >2 and ≤7 | 78 (38.4) | 113 (49.1) | |

| >7 | 12 (5.9) | 35 (15.2) | |

| Glasgow Coma Scale score (mean ± SD) | 13.80 ± 2.15 | 12.57 ± 3.05 | <0.001 |

| New-onset convulsionc | 31 (15.1) | 60 (26.2) | 0.005 |

| Immunosuppressiond | 24 (11.7) | 35 (15.1) | 0.29 |

Values are no. (%) of patients, unless otherwise indicated.

Elapsed time between onset of symptoms (OS) and the start of antiviral treatment (AVT).

Defined as a convulsion observed before therapy.

Defined as long-term steroid use or other immunosuppressive state.

TABLE 3.

Final model, including independent predictors of unfavorable outcome

| Variable | ORa | 95% CI |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | |||

| Age (yr) | 1.04 | 1.02 | 1.05 | 0.000 |

| Glasgow Coma Scale score | 0.84 | 0.77 | 0.93 | 0.000 |

| Elapsed time (days)b | ||||

| >2 and ≤7 | 1.80 | 1.16 | 2.79 | 0.009 |

| >7 | 3.75 | 1.72 | 8.15 | 0.001 |

OR, odds ratio.

Elapsed time between onset of symptoms and administration of antiviral treatment.

This multivariate model found that a delay in establishing an effective antiviral treatment significantly increases the risk of unfavorable outcome. Accordingly, a delay of >7 days causes a significant increase in unfavorable outcome among patients. This is documented by the multivariate model, in which the odds ratio for a delay in the onset of aciclovir treatment of >7 days being 3.75 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.72 to 8.15) and that for 2 to 7 days being 1.80 (95% CI, 1.16 to 2.79) are significant, whereas the odds ratio for ≤2 days being 0.48 (95% CI, 0.32 to 0.74; P = 0.001) is protective (estimates made by univariate logistic regression).

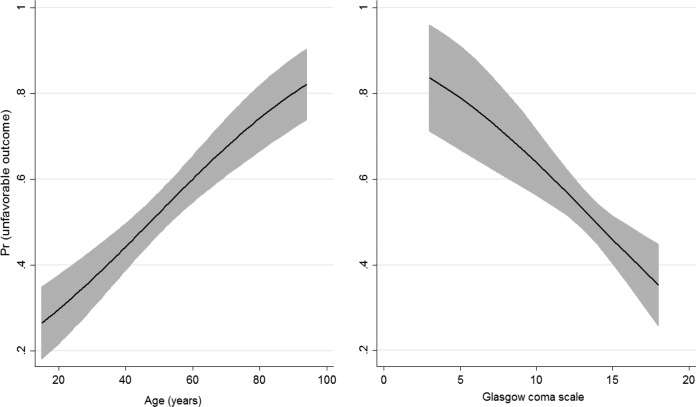

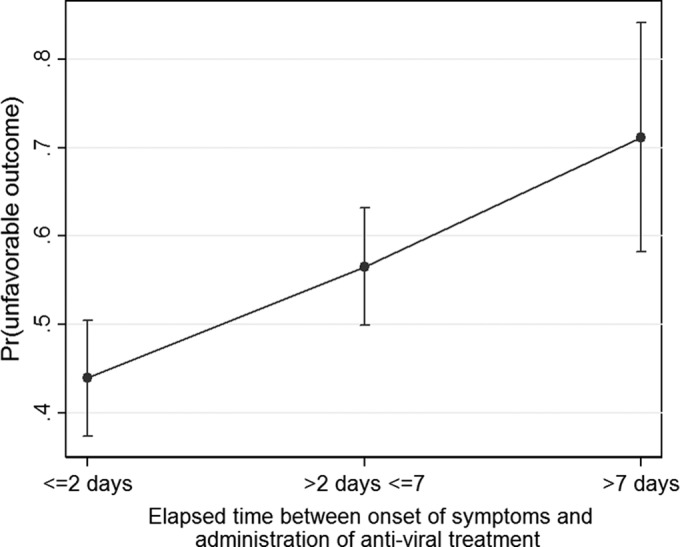

The predicted percentages of unfavorable outcome versus elapsed time since the onset of symptoms are presented in Fig. 1, where unfavorable outcome increases from 0.44 to 0.71 depending on the delay in establishing an effective antiviral treatment. The observed outcomes against the predicted outcomes estimated by the logistic regression analysis were in perfect agreement (Fig. 2).

FIG 1.

Predictions (Pr, probability) of antiviral treatment timing for unfavorable outcome. The data are presented as the mean values with the 95% CI.

FIG 2.

Observed outcomes against predicted outcomes estimated by the model.

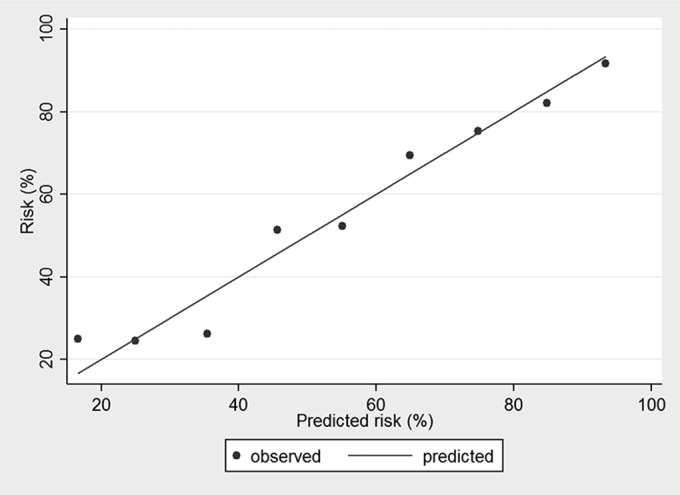

The multivariate model documented that age and GCS score independently predict unfavorable outcome. The relationship between these and outcome is shown in Fig. 3. Briefly, unfavorable outcome was more frequent with increasing age, at >80% among the geriatric patients. An interaction between age and male gender was also found, indicating that elderly males experienced more unfavorable outcomes. Lower GCS scores were found to be associated with more unfavorable outcome, at >80% in patients with scores lower than five.

FIG 3.

Predictive margins of age and Glasgow Coma Scale score on unfavorable outcome. The data are presented as the mean values with the 95% CI.

DISCUSSION

There are a number of published reports with relatively small case series assessing unfavorable outcome in HME. Advanced age (10, 18, 19), lower GCS score (10), greater extent of brain involvement (20, 21), low serum albumin level (18), longer duration of disease (20), delayed aciclovir use (18, 19, 21–24), the presence of red blood cells in the CSF (19), and immunosuppression (24) have been found to be associated with poorer outcomes in HME. In this study, we detected that a combination of therapeutic and host factors contributed to the outcomes in HME patients. Advancing age, delayed start of antivirals, and worsening of consciousness determined by the GCS contributed to the development of unfavorable outcomes in these patients. In a relatively large study by Raschilas (22), higher Simplified Acute Physiology Score II and a delay in the initiation of antiviral therapy were associated with poor prognosis. These results are quite in accordance with those of this study. On the other hand, the data in the literature related to the efficacy of treatment in HSV-2 meningitis are rather unclear (25, 26).The host parameters directly affect the course of central nervous system (CNS) infections. In different types of CNS infections, increasing age and lower GCS scores have long been known to be associated with poor outcomes (27–29). Our HME data were also in accordance with those regarding other infectious CNS disorders and with the initial reports of adult HME series (10, 18, 19). According to our results, patients with a GCS score of less than five experienced unfavorable outcome more frequently. Added to that, older males were more likely than were others to have unfavorable outcomes from HME. Convulsions are also believed to occur in patients with poor outcomes (30). In this study, we did not determine a significant relationship between new-onset convulsions and poor outcome in HME patients.

In daily medical practice, the use of aciclovir at standard dosages has been reported to be of paramount importance in HME patients (1, 3, 8). However, the importance of the optimal timing of aciclovir administration in the improvement of outcomes has been unclear. Added to that, the benefit of the empirical use of aciclovir in patients with a likely diagnosis of encephalitis, rather than in those with confirmed HSV encephalitis, has not yet been proven in a randomized controlled clinical trial (1). In a previous study (31), 17 out of 24 (71%) of patients with suspected encephalitis did not receive empirical aciclovir in the emergency department but rather after inpatient admission (median time, 16 h; 95% CI, 7.5 to 44 h). In this study, three of five confirmed HSV encephalitis cases were not given aciclovir in the emergency department (31). In a large previous study (22), a mean ± SD delay of 5.5 ± 2.9 days elapsed between the onset of symptoms and the initiation of antiviral treatment. These data indicate that an early start to antiviral treatment in HME patients is not likely. This study suggests that aciclovir administered within the first 2 days after the onset of symptoms significantly contributed to better outcomes. The goal of empirical antiviral treatment is to improve the prognoses in patients who are ultimately proven to have HME. Thus, suspected encephalitis patients should urgently be given antiviral treatment when the results of diagnostic studies are pending.

Although it would be very difficult to prospectively provide such a large cohort, the major limitation of this study is its retrospective design. The discrimination between pure meningitis and pure encephalitis is very difficult in a retrospective study, since they have been known to be two interrelated syndromes with quite similar clinical presentations; thus, we cautiously erred in favor of not discriminating between these two diseases. On the other hand, the major problem was the microbiological confirmation of HSV cases due to diagnostic difficulties in previous studies (32, 33). Since PCR testing in the CSF has an overall sensitivity and specificity of >95% with HME (8), we view the inclusion of only CSF-PCR-positive cases to be a strength of the study. Added to that, the predicted and observed probabilities of the final model in this study were in perfect agreement.

In conclusion, the outcome in HME patients is directly related to both therapeutic and host factors. Host factors, like age, gender, unconsciousness, and seizures, detected during initial evaluation, as well as coexistent immunosuppressive conditions, may not be preventable for the treating clinician. However, the major concerns should be both the rapid diagnosis and early start to antiviral treatment in either suspected or proven HME cases.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beckham JD, Tyler KL. 2015. Encephalitis, p 1144–1163. In Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ (ed), Mandell, Douglass, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases, 8th ed Elsevier Co., Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hjalmarsson A, Blomqvist P, Skoldenberg B. 2007. Herpes simplex encephalitis in Sweden, 1990–2001: incidence, morbidity, and mortality. Clin Infect Dis 45:875–880. doi: 10.1086/521262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tunkel AR, Glaser CA, Bloch KC, Sejvar JJ, Marra CM, Roos KL, Hartman BJ, Kaplan SL, Scheld WM, Whitley RJ, Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2008. The management of encephalitis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 47:303–327. doi: 10.1086/589747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michael BD, Sidhu M, Stoeter D, Roberts M, Beeching NJ, Bonington A, Hart IJ, Kneen R, Miller A, Solomon T, North West Neurological Infections Network. 2010. Acute central nervous system infections in adults–a retrospective cohort study in the NHS North West region. QJM 103:749–758. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcq121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stahl JP, Mailles A, De Broucker T, Steering Committee and Investigators Group. 2012. Herpes simplex encephalitis and management of acyclovir in encephalitis patients in France. Epidemiol Infect 140:372–381. doi: 10.1017/S0950268811000483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pewter SM, Williams WH, Haslam C, Kay JM. 2007. Neuropsychological and psychiatric profiles in acute encephalitis in adults. Neuropsychol Rehabil 17:478–505. doi: 10.1080/09602010701202238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dagsdóttir HM, Sigurethardóttir B, Gottfreethsson M, Kristjansson M, Love A, Baldvinsdóttir GE, Guethmundsson S. 2014. Herpes simplex encephalitis in Iceland 1987–2011. Springerplus 3:524. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solomon T, Michael BD, Smith PE, Sanderson F, Davies NW, Hart IJ, Holland M, Easton A, Buckley C, Kneen R, Beeching NJ, National Encephalitis Guidelines Development and Stakeholder Groups. 2012. Management of suspected viral encephalitis in adults–Association of British Neurologists and British Infection Association National Guidelines. J Infect 64:347–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sköldenberg B, Forsgren M, Alestig K, Bergström T, Burman L, Dahlqvist E, Forkman A, Fryden A, Lövgren K, Norlin K, Olding-Stenkvist I, Uhnoo I, De Vahl K. 1984. Acyclovir versus vidarabine in herpes simplex encephalitis. Randomised multicentre study in consecutive Swedish patients. Lancet ii:707–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitley RJ, Alford CA, Hirsch MS, Schooley RT, Luby JP, Aoki FY, Hanley D, Nahmias AJ, Soong SJ. 1986. Vidarabine versus acyclovir therapy in herpes simplex encephalitis. N Engl J Med 314:144–149. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198601163140303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Child N, Croxson MC, Rahnama F, Anderson NE. 2012. A retrospective review of acute encephalitis in adults in Auckland over a five-year period (2005–2009). J Clin Neurosci 19:1483–1485. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Modi A, Atam V, Jain N, Gutch M, Verma R. 2012. The etiological diagnosis and outcome in patients of acute febrile encephalopathy: a prospective observational study at tertiary care center. Neurol India 60:168–173. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.96394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mailles A, Stahl JP, Steering Committee and Investigators Group. 2009. Infectious encephalitis in France in 2007: a national prospective study. Clin Infect Dis 49:1838–1847. doi: 10.1086/648419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Studahl M, Lindquist L, Eriksson BM, Gunther G, Bengner M, Franzen-Rohl E, Fohlman J, Bergstrom T, Aurelius E. 2013. Acute viral infections of the central nervous system in immunocompetent adults: diagnosis and management. Drugs 73:131–158. doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tunkel AR, Hartman BJ, Kaplan SL, Kaufman BA, Roos KL, Scheld WM, Whitley RJ. 2004. Practice guidelines for the management of bacterial meningitis. Clin Infect Dis 39:1267–1284. doi: 10.1086/425368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tunkel AR, van de Beek D, Scheld MW. 2015. Acute meningitis, p 1097–1137. In Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ (ed), Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases, 8th ed Elsevier Co., Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sauerbrei W, Schumacher M. 1992. A bootstrap resampling procedure for model building: application to the Cox regression model. Stat Med 11:2093–2109. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780111607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riera-Mestre A, Gubieras L, Martinez-Yelamos S, Cabellos C, Fernandez-Viladrich P. 2009. Adult herpes simplex encephalitis: fifteen years' experience. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 27:143–147. doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poissy J, Champenois K, Dewilde A, Melliez H, Georges H, Senneville E, Yazdanpanah Y. 2012. Impact of herpes simplex virus load and red blood cells in cerebrospinal fluid upon herpes simplex meningo-encephalitis outcome. BMC Infect Dis 12:356. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sili U, Kaya A, Mert A, HSV Encephalitis Study Group. 2014. Herpes simplex virus encephalitis: clinical manifestations, diagnosis and outcome in 106 adult patients. J Clin Virol 60:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaplan CP, Bain KP. 1999. Cognitive outcome after emergent treatment of acute herpes simplex encephalitis with acyclovir. Brain Inj 13:935–941. doi: 10.1080/026990599121133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raschilas F, Wolff M, Delatour F, Chaffaut C, De Broucker T, Chevret S, Lebon P, Canton P, Rozenberg F. 2002. Outcome of and prognostic factors for herpes simplex encephalitis in adult patients: results of a multicenter study. Clin Infect Dis 35:254–260. doi: 10.1086/341405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheybani F, Arabikhan HR, Naderi HR. 2013. Herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE) and its outcome in the patients who were admitted to a tertiary care hospital in Mashhad, Iran, over a 10-year period. J Clin Diagn Res 7:1626–1628. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/5661.3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan IL, McArthur JC, Venkatesan A, Nath A. 2012. Atypical manifestations and poor outcome of herpes simplex encephalitis in the immunocompromised. Neurology 79:2125–2132. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182752ceb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ihekwaba UK, Kudesia G, McKendrick MW. 2008. Clinical features of viral meningitis in adults: significant differences in cerebrospinal fluid findings among herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster virus, and enterovirus infections. Clin Infect Dis 47:783–789. doi: 10.1086/591129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landry ML, Greenwold J, Vikram HR. 2009. Herpes simplex type-2 meningitis: presentation and lack of standardized therapy. Am J Med 122:688–691. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Misra UK, Kalita J, Roy AK, Mandal SK, Srivastava M. 2000. Role of clinical, radiological, and neurophysiological changes in predicting the outcome of tuberculous meningitis: a multivariable analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 68:300–303. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.68.3.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erdem H, Elaldi N, Oztoprak N, Sengoz G, Ak O, Kaya S, Inan A, Nayman-Alpat S, Ulu-Kilic A, Pekok AU, Gunduz A, Gozel MG, Pehlivanoglu F, Yasar K, Yilmaz H, Hatipoglu M, Cicek-Senturk G, Akcam FZ, Inkaya AC, Kazak E, Sagmak-Tartar A, Tekin R, Ozturk-Engin D, Ersoy Y, Sipahi OR, Guven T, Tuncer-Ertem G, Alabay S, Akbulut A, Balkan II, Oncul O, Cetin B, Dayan S, Ersoz G, Karakas A, Ozgunes N, Sener A, Yesilkaya A, Erturk A, Gundes S, Karabay O, Sirmatel F, Tosun S, Turhan V, Yalci A, Akkoyunlu Y, Aydin E, Diktas H, Kose S, Ulcay A, Seyman D, Savasci U, Leblebicioglu H, Vahaboglu H. 2014. Mortality indicators in pneumococcal meningitis: therapeutic implications. Int J Infect Dis 19:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erdem H, Kilic S, Coskun O, Ersoy Y, Cagatay A, Onguru P, Alp S, Members of the Turkish Bacterial Meningitis in the Elderly Study Group. 2010. Community-acquired acute bacterial meningitis in the elderly in Turkey. Clin Microbiol Infect 16:1223–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pandey S, Rathore C, Michael BD. 2014. Antiepileptic drugs for the primary and secondary prevention of seizures in viral encephalitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 10:CD010247. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010247.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benson PC, Swadron SP. 2006. Empiric acyclovir is infrequently initiated in the emergency department to patients ultimately diagnosed with encephalitis. Ann Emerg Med 47:100–105. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitley RJ, Cobbs CG, Alford CA Jr, Soong SJ, Hirsch MS, Connor JD, Corey L, Hanley DF, Levin M, Powell DA. 1989. Diseases that mimic herpes simplex encephalitis. Diagnosis, presentation, and outcome. NIAD Collaborative Antiviral Study Group. JAMA 262:234–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whitley RJ, Soong SJ, Linneman C Jr, Liu C, Pazin G, Alford CA. 1982. Herpes simplex encephalitis. Clinical assessment. JAMA 247:317–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]