Background: PDE6, the rod photoreceptor phosphodiesterase, is the key effector enzyme in phototransduction.

Results: EM reconstructions of PDE6 complexed with various probes are presented.

Conclusion: Fitting of x-ray structures yielded an atomic model of the catalytic subunits, and the locations of other structural features are indicated.

Significance: These data offer the most complete view to date of the PDE6 holoenzyme.

Keywords: conformational change, cryo-electron microscopy, phosphodiesterases, phototransduction, retina, tertiary structure

Abstract

The cGMP phosphodiesterase of rod photoreceptor cells, PDE6, is the key effector enzyme in phototransduction. Two large catalytic subunits, PDE6α and -β, each contain one catalytic domain and two non-catalytic GAF domains, whereas two small inhibitory PDE6γ subunits allow tight regulation by the G protein transducin. The structure of holo-PDE6 in complex with the ROS-1 antibody Fab fragment was determined by cryo-electron microscopy. The ∼11 Å map revealed previously unseen features of PDE6, and each domain was readily fit with high resolution structures. A structure of PDE6 in complex with prenyl-binding protein (PrBP/δ) indicated the location of the PDE6 C-terminal prenylations. Reconstructions of complexes with Fab fragments bound to N or C termini of PDE6γ revealed that PDE6γ stretches from the catalytic domain at one end of the holoenzyme to the GAF-A domain at the other. Removal of PDE6γ caused dramatic structural rearrangements, which were reversed upon its restoration.

Introduction

Members of the type I family of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases, comprising PDE1-PDE113 (1, 2), operate in a sink-source relationship with cyclase enzymes to control the levels of the key second messengers cGMP and cAMP. PDEs are targets of several widely used drugs and remain a major target for drug development. The family is defined by a conserved catalytic domain, outside of which family members display diverse domain structures and regulatory mechanisms. Five mammalian subfamilies contain non-catalytic cyclic nucleotide binding regulatory GAF domains: PDE2, PDE5, PDE6, PDE10, and PDE11. The cGMP-specific PDE6 isozymes of vertebrate rod and cone photoreceptors are unique in containing two tightly bound inhibitory γ subunits (3, 4). PDE6 is a heterotetramer containing two γ subunits as well as the homologous α and β subunits in rods (PDE6αβγγ) or the related α′ subunits in cones (PDE6α′α′γγ). Each α or β subunit contains two N-terminal GAF domains (GAFa and GAFb) and a C-terminal catalytic domain. High resolution structures are available for isolated domains or fragments of PDE isozymes, including PDE6 and PDE5 (5–10), and a crystal structure of nearly full-length PDE2A (11) includes both GAF and catalytic domains. Although several low resolution structures of PDE6 based on electron microscopy in negative stain have been published (12–14), the structural relationships between the GAF and catalytic domains is unknown. In addition, the location and conformation of the PDE6γ subunits are largely unknown.

PDE6γ binds to the catalytic domains of α/β subunits, where its C-terminal residues block the active site (10, 15–20, 63). In the course of the phototransduction cascade, the G protein transducin α subunit (Gαt) sequesters the PDE6γ C terminus, relieving the inhibition (5, 17, 21). PDE6γ binding is also strongly coupled to cGMP binding at noncatalytic sites in the GAFa domain (22–26). Such interdomain regulation by the 9.7-kDa PDE6γ polypeptide requires either proximity of GAFa and catalytic domains in the quaternary structure, a highly extended conformation for PDE6γ, or long range allosteric control. Cross-linking studies (20, 27, 64) support a PDE6γ extended conformation, with contact made between PDE6γ and all three domains of the catalytic subunits, but direct structural evidence is lacking.

We have used cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to determine the overall structure of PDE6. The higher resolution map revealed previously unseen features of the PDE6 structure and permitted definitive orientation of the GAF domains. Visualization of antibody Fab fragments bound to the C or N terminus of PDE6γ was used to investigate the positioning of the inhibitory subunit in the holoenzyme, and imaging of PDE6·PrBP/δ complexes revealed the locations of the PrBP/δ binding sites and the C-terminal prenylations of PDE6α/β. Finally, we characterized a dramatic structural rearrangement of the catalytic subunits in the absence of PDE6γ.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Extraction and Purification of PDE6

Extraction and purification of PDE6 from bovine rod outer segment (ROS) membranes were as described (28). Briefly, ROS were prepared from 300 frozen dark-adapted bovine retinas (InVision BioResources, Seattle, WA) and purified by sucrose gradient fractionation. For PDE6 purification, several ROS preparations were pooled, bleached in room light, and sequentially washed with moderate salt buffer (10 mm MOPS, pH 7.4, 30 mm NaCl, 60 mm KCl, 2 mm MgCl2) and low salt buffer (5 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 0.5 mm MgCl2) to produce a highly-enriched PDE6 extract. PDE6 was purified with hydroxyapatite chromatography (Bio-Rad) using a step gradient elution with phosphate buffers to remove HSP90 contamination (28) followed by HPLC gel filtration using a Bio-Sil SEC 250–5 column (Bio-Rad). Purified PDE6 was concentrated with a Centricon-50 (Millipore) and stored in 20 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 2 mm DTT, and 40% glycerol at −20 °C.

PDE6 used for complex formation with PrBP/δ was purified from 800 bovine retinas as previously described (3). Briefly, ROS membranes were purified by sucrose gradient centrifugation and washed 5 times with isotonic buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.1 m NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.1 mm DTT) followed by hypotonic buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mm EDTA, 0.1 mm DTT). Hypotonic supernatants were concentrated using Vivaspin 15 concentrators (Sartorius Stedim, Goettingen Germany). PDE6 was purified by gel filtration chromatography (SD200, Amersham Biosciences/GE Healthcare) in 100 mm NaCl, 10 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 1 mm DTT. Typical yields were ∼1.5 mg of ∼99% pure PDE6.

Purification of Fab Fragments

ROS-1 hybriboma cells (29) were kindly provided by Dr. Richard L. Hurwitz (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston TX), and ascites fluid containing ROS-1 monoclonal antibody (mAb) was produced by Maine Biotechnology Services, Inc. (Portland, ME). ROS-1 mAb was purified with ImmunoPure Immobilized protein L (Pierce) following the manufacturer's instructions. The pure fractions of ROS-1 mAb were pooled and dialyzed against digestion buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 7.6, 50 mm NaCl, 1.25 mm EDTA, 20 mm cysteine). Purified ROS-1 mAb was concentrated and digested with papain (Sigma) at a ratio of 10 μg of papain to 1 mg of mAb in digestion buffer at 37 °C for at least 4 h. After confirming by SDS-PAGE that the digestion was complete, the protease was inactivated by incubating with 75 mm iodoacetamide at room temperature for 30 min. The Fab fragment was purified using ImmunoPure Immobilized protein L. For human influenza hemagglutinin (HA) Fab, HA mAb clone 16B12 (Covance) was digested with papain as above. The Fab fragment was purified with a BioSuite weak-cation exchange CM column (Waters) in a gradient of 30 mm MES, pH 6.3, versus 30 mm MES, pH 6.3, with 1 m sodium acetate and a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The purity of the Fab fragments was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining.

Expression and Purification of Recombinant PDE6γ

Synthetic bovine PDE6γ subunit cDNA (30) was subcloned into to the pET14b vector (Novagen), thereby adding an N-terminal His6 tag. PDEγ constructs containing the N-terminal His6 tag as well as the HA epitope (YPYDVPDYA) at either the N or C terminus, separated from the PDE6γ sequence by the linker SGGGGS, were cloned by PCR. Recombinant PDE6γ was expressed in BL21(DE3)pLysS Escherichia coli (Novagen). PDE6γ in inclusion bodies was solubilized with 6 m guanidinium chloride and purified with a Ni-NTA Fastflow (Qiagen) column under denaturing conditions following the manufacturer's protocol followed by a HPLC C4 reverse-phase column (VyDac, Discovery Sciences) as described (31). Purified recombinant PDE6γ was lyophilized by SpeedVac to remove acetonitrile and trifluoroacetic acid and stored at −80 °C.

Preparation of PDE6·ROS-1-Fab Complexes

Purified ROS-1 Fab was mixed with purified PDE6 at a Fab:PDE6 molar ratio of 2:1 and incubated at 4 °C for 30 min. The complex was purified by gel filtration (Bio-Sil SEC-250-5, Bio-Rad) in 20 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl. The pure complexes were examined by SDS-PAGE, concentrated, filtered through a 0.2-μm spin-X cellulose acetate filter (Costar), and used directly for cryo-EM.

Limited Proteolysis of PDE6 and Preparation of PDE6·HA-Fab Complexes

Purified PDE6 was treated with trypsin in PDE6 assay buffer (10 mm MOPS, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm MgCl2, and 0.1 mm EDTA) for 8 min at room temperature at a PDE6:trypsin molar ratio of 100:1. Soybean trypsin inhibitor (Sigma) was added at a 10-fold molar excess over trypsin to terminate the proteolysis. Trypsinized PDE6 (tPDE6) was purified by gel filtration (Bio-Sil SEC-250-5, Bio-Rad) in 20 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 100 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgCl2. The activity of tPDE6 was monitored with a pH assay (28, 32).

To prepare PDE6·HA-Fab complexes, purified tPDE6 was mixed with HA-Fab and N or C terminally HA-tagged PDE6γ at a molar ratio of 1:2.5:2.5 and incubated at 4 °C for 4 h. Complexes were purified by gel filtration as above. All recombinant PDE6γ proteins were tested for inhibitory function, indicating catalytic domain binding, as well as for mediation of cGMP binding to the GAF domain.

Expression and Purification of Recombinant Human PrBP/δ

PrBP/δ cDNA was amplified by PCR from a human retina cDNA library and cloned into a pET151/D-TOPO vector (Invitrogen). The construct was expressed in BL21 Codon+ E. coli cells (Stratagene) in ZY autoinduction media for 6 h at 37 °C and then overnight at 19 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended, and lysed with 10 mg/ml lysozyme in lysis buffer (20 mm imidazole, 700 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris pH 7.4, 1 mm DTT) and protease inhibitors (PMSF, aprotinin, leupeptin, pepstatin) for 1 h at 4 °C followed by sonication. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation, and soluble PrBP/δ protein was bound to a Ni2+-Sepharose column (Amersham Biosciences/GE Healthcare), washed with 10 column volumes of lysis buffer, and eluted with 300 mm imidazole in 700 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris, pH 7.4, and 1 mm DTT. Fractions were assayed by SDS-PAGE, pooled, and dialyzed against 2 liters of 20 mm NaCl, 25 mm Tris, pH 7.4, and 1 mm DTT. PrBP/δ was purified to homogeneity by anion exchange (HiTrap Q FF, GE Healthcare Life Sciences) with a 20–1000 mm NaCl gradient in 25 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 1 mm DTT, and gel filtration (SD200, Amersham Biosciences/GE Healthcare) in 100 mm NaCl, 10 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 1 mm DTT.

Preparation of PDE6·PrBP/δ Complexes

A 3-fold molar excess of pure recombinant PrBP/δ was added to purified PDE6 and incubated at 4 °C for a minimum of 4 h. The complex was purified by gel filtration chromatography (SD200, Amersham Biosciences/GE Healthcare) in 10 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT. Fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and pure fractions were combined and concentrated. The complex was stored in 40% glycerol at −20 °C.

PDE6·PrBP/δ complexes were dialyzed against gel filtration buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgCl2) at 4 °C overnight to remove glycerol, concentrated with a Centricon-50, and purified by gel filtration (Bio-Rad, Bio-Sil SEC 250–5) in gel filtration buffer. The purity of the fractions was confirmed by SDS-PAGE, and the peak fractions were pooled and diluted to 0.2–0.3 mg/ml with gel filtration buffer. In some experiments, complexes were dialyzed, concentrated, filtered through a 0.2-μm cellulose acetate filter, and used directly for cryo-EM.

cGMP Binding Assay

To determine whether the HA-tagged PDE6γ could regulate cGMP binding to the non-catalytic sites in the GAF domains of PDE6αβ, cGMP binding in the non-catalytic sites was measured using a modification of the assay described by Cote (33). tPDE6 in 10 mm MOPS, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm MgCl2, and 0.1 mm EDTA was incubated at 30 °C for 2 h to deplete the endogenous cGMP and purified by gel filtration. The cGMP-free tPDE6 was reconstituted with HA-tagged PDE6γ as described above. The reconstituted PDE6 was incubated in 20 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl with or without additional trypsin for 90 s at room temperature. Soybean trypsin inhibitor was added at a 10-fold molar excess over trypsin in all samples, then the reaction buffer was added to give final concentrations of 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 30 mm NaCl, 60 mm KCl, 1 mm phosphate, protease inhibitor mixture (2 μg/ml aprotinin, 2 μg/ml chymostatin, 0.5 μg/ml leupeptin, 0.7 μg/ml pepstatin A, 30 μg/ml trypsin inhibitor, 1.56 mg/ml benzamide, 0.1 μm E64, and 0.16 mm Pefabloc), 0.5 mg/ml ovalbumin, 1 mm zaprinast, and 0.1 mm EDTA. The samples were incubated with 1.5 μm cGMP solution containing [3H]cGMP (Amersham Biosciences) at room temperature for 3 or 20 min. 60 μl of the reaction mixture was directly filtered through pre-wet nitrocellulose membranes (Type HA, 0.45 μm, Millipore) in a vacuum manifold (Hoefer Scientific Instruments) and quickly rinsed 3 times with 3 ml of ice-cold buffered ammonium sulfate (10 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 95% saturated ammonium sulfate). [3H]cGMP retained on the membranes was quantified by scintillation counting.

Electron Microscopy

For cryo-electron microscopy, protein solutions at 0.2–0.5 mg/ml were applied to glow-discharged Quantifoil grids (Quantifoil Micro Tools) with 2.0-μm holes. A Vitrobot Mark III (FEI) set to 22 °C and 95% humidity was used for freezing. Images in ice were obtained using a JEOL2010F microscope equipped with a Gatan liquid nitrogen cryoholder and 4k × 4k CCD camera. CCD images were acquired using a dose of 15–18 e/Å2 and magnification of 60,000 × (1.81 Å/pixel). For negative stains, specimens were applied to carbon-coated copper grids and stained with 2% uranyl acetate. PDE6 and tPDE6 samples in negative stain were imaged for single-particle data collection with a JEOL 1200EX microscope at 100 KV at a dose of 15–18 e/Å2 and a magnification of 60,000×. For tomogram data collection tPDE6 samples were imaged with a JEM2100 microscope with SerialEM software (34) at 200 KV. Single-axis tilt series of negatively stained grids were collected from −60 to +60° in 2° increments with an average dose of 25 e/Å2 per micrograph and magnification of 60,000× (1.82 Å/pixel).

Image processing was performed using EMAN (35). For processing images of ice-embedded PDE6, 12,970 particles were selected and corrected for the contrast transfer function using Ctfit. The structure was refined using C1 symmetry and either an initial model generated from reference-free class averages or a cylinder starting model. The two refined models were essentially similar. After multiple rounds of iterative alignment, classification, reconstruction, and refinement, a final C1 three-dimensional map was generated from a set of 9200 particles and low-pass filtered to 22 Å.

For the PDE6·ROS-1-Fab complex, a total of 21,100 particles were picked from ice images and corrected for the contrast transfer function using Ctfit. After an initial three-dimensional model was generated as described for PDE6, three noise-seeded models were generated and used as initial models in the Multirefine procedure. A model with two Ros-1 Fabs bound with a population of ∼15,000 particles emerged and was subject to further refinement using standard iterative projection matching, class averaging, and Fourier reconstruction. The final three-dimensional maps with C1 and C2 symmetry were generated from 12,373 particles. The resolution was determined by splitting data into even and odd halves to generate a “gold standard” Fourier shell correlation (FSC) curve, which indicated a resolution of ∼18 Å and ∼17 Å for the C1 and C2 models, respectively, at FSC = 0.5 and ∼11 Å at FSC = 0.143. The PDE6·ROS-1-Fab map has been deposited in the EMDataBank with accession code EMD-6258.

PDE6·HA-Fab complexes were imaged in ice. For the N-terminally labeled complex, ∼13,000 particles of PDE6·HA-PDE6γ·HA-Fab were subjected to multiple iterations of Multirefine using different starting models, as described for the PDE6·ROS-1-Fab complex, generating three final models. The particles corresponding to the model with the largest population (∼8500 particles) were used to generate an averaged map that was low-pass-filtered at 30 Å resolution. The same procedure was used for the C-terminally labeled complex (PDE6·PDE6γ-HA·HA-Fab). Starting with ∼8000 particles, three models were generated with Multirefine, and the ∼4500 particles corresponding to the most populated conformation were selected and used to generate an averaged map and low-pass-filtered at 30 Å.

For the PDE6·PrBP/δ complex imaged in ice, a total of ∼4100 particles (with both single and double occupancy of the two PrBP/δ binding sites) were selected and used for standard refinement procedures in EMAN. A low resolution map (30 Å) of PDE6 generated from ice images was used as the starting model for the iterative refinement procedure. The consistency between projections of the three-dimensional reconstruction and reference-based class averages supports the accuracy of the map. The final three-dimensional map with C2 symmetry imposed was generated from ∼3500 particles and low-pass-filtered to 30 Å. A low resolution map of negatively stained PDE6 was constructed from about 1000 particles, as described above for PDE6·PrBP/δ.

tPDE6 tilt series alignment and three-dimensional tomographic reconstruction were performed with IMOD software (36). For standard single-particle analysis of tPDE6, 4100 negatively stained particles were picked from 45 micrographs (inclined from +40.26° to −47.82°) and subjected to Multirefine based on three starting models with C2 symmetry imposed. The resulting three subgroups contained 1450, 1370, and 1280 particles, and the final models were low-pass-filtered at 30 Å after a single iterative refinement with C2 symmetry. Similar models were obtained from an independent data set of 15,560 negatively stained particles imaged without tilt (not shown). For single-particle tomography, 120 sub-volumes were averaged with or without C2 symmetry imposed.

Fitting of GAFa, GAFb, and Fab x-ray structures into the PDE6·ROS-1-Fab map was performed using UCSF Chimera (37). Fitting results for GAFb and Fab structures were confirmed with Foldhunter (38). Fitting of the PDE catalytic domain was done manually, with constraints as described under “Results.” Fitting of PrBP/δ and Fab in low resolution maps was done manually. Molecular graphics were rendered using Chimera (37) and PyMOL (Schrödinger).

RESULTS

Low Resolution Structure of PDE6 in Vitreous Ice

A typical field of PDE6 molecules suspended in vitreous ice is shown in Fig. 1A. Despite the much lower image contrast obtained in ice, bell-like “front” views resembling those previously observed in negative stain (12–14) could clearly be seen as well as less feature-rich views representing side or top/bottom orientations. A final map was generated from ∼9200 particles (Fig. 1C), and comparison of class averages and corresponding model projections (Fig. 1B) indicates good agreement of the model with the data.

FIGURE 1.

Three-dimensional structure of PDE6. A, a field of PDE6 suspended in vitreous ice. Scale bar, 200 Å. B, comparison of model projections (left) and corresponding class averages (right). C, three-dimensional map of PDE6. The map is filtered to 22 Å and displayed at an isosurface threshold approximating the PDE6 molecular mass of 220 kDa. Scale bar, 40 Å.

The overall appearance of the map is similar to that of previously reported models of PDE6 imaged in negative stain (12–14), exhibiting a flattened and extended shape with two prominent cavities. Most of the structure has an approximate 2-fold symmetry as a consequence of the 84% sequence similarity between the PDE6α and PDE6β subunits. There is a clear asymmetry in the top portion, which has previously been attributed to the N terminus of PDE6α/β (13), where the homology between PDEα and PDE6β is low, with 31% identity in the first 90 amino acids compared with 74% overall.

Improved Resolution Using PDE6·ROS-1-Fab Complexes and 2-Fold Symmetry

To provide greater mass and additional features to improve alignment, PDE6 was imaged in complex with the ROS-1 Fab (Fig. 2). Compared with PDE6 alone, front and top/bottom views of PDE6·ROS-1-Fab complexes contain clearly visible extra density on two sides (Fig. 2A). A three-dimensional reconstruction was generated from 12,373 particles in vitreous ice (Fig. 2). The overall shape of the PDE6·ROS-1-Fab three-dimensional structure is similar to that of PDE6 alone, with the addition of extra density protruding from the bottom in approximately 2-fold symmetrical positions (Fig. 3A). This extra density is well fit by a Fab molecule (Fig. 3B), providing unambiguous assignment as the ROS-1-Fab and localization of the ROS-1 binding site. This antibody has high affinity for the holo-PDE6 complex, PDE6αβγγ, but low affinity for either PDE6γ or PDE6αβ, and its binding inhibits activation of PDE6 by trypsin, histone 2B, or activated G protein (29, 39–41).4 These observations suggest that ROS-1 specifically recognizes the complex of PDE6γ with the catalytic subunits and likely binds at the interface between them. The 2-fold symmetry indicates that the two ROS-1 binding sites are likely composed of structurally similar sites on PDE6α/γ and PDE6β/γ, and the catalytic domains are related to one another in an approximately symmetric way.

FIGURE 2.

Three-dimensional structure of PDE6·ROS-1-Fab. A, a field of PDE6·ROS-1-Fab complexes suspended in vitreous ice. Examples of front, side, and top/bottom views are indicated with circles, hexagons, and squares, respectively. Scale bar, 200 Å. Inset, class averages of front and top/bottom views, with extra density indicated by arrows. B, three-dimensional maps with no symmetry (C1) or 2-fold rotational symmetry (C2) imposed during reconstruction. Three different views of the reconstruction are shown at 100% isosurface volume according to the molecular mass of the PDE6·ROS-1-Fab complex (320 kDa). Lines shown in the bottom view (iii) indicate the plane of the page in i and ii. Scale bar, 40 Å. C, enlarged view of the GAF domains in the C1 and C2 maps shown at a higher density threshold level. D, distribution of particle orientations. E, gold standard FSC curves for PDE6·ROS-1-Fab C1 and C2 maps indicate a resolution of ∼18.4 and ∼17.3 Å, respectively, at FSC = 0.5 and ∼11 Å at FSC = 0.143.

FIGURE 3.

Fab fitting in the PDE6·ROS-1-Fab structure. A, superposition of the PDE6·ROS-1-Fab C1 map, filtered to 22 Å (gray), with the PDE6 map (cyan). B, crystal structure of an Fab fragment (PDB ID 12E8 (62)) with surface low-pass filtered to 11 Å (top). Fitting of the Fab structure into the PDE6·ROS-1-Fab C1 and C2 maps (middle, bottom). Complementarity-determining regions for 12E8 are shown in green.

To further improve the resolution, C2 symmetry was imposed during the reconstruction, yielding a final map with resolution of ∼17 Å by the conservative 0.5 FSC criterion and ∼11 Å by the alternative criterion of 0.143 FSC (42) (Fig. 2E). The overall shape of the C1 and C2 maps are similar (Fig. 2, B and C). Although asymmetric features such as the PDE6α/β N terminus are averaged out by symmetry imposition, other structures of the GAF and catalytic domains are more clearly revealed.

The greatly improved resolution of this structure compared with that of PDE6 alone is highlighted by the clear visualization of α helices in the catalytic subunits and the cavity between the constant and variable domains of the Fab, which is <5 Å wide. The new structure reveals a long dimer interface between the GAF domains of PDE6α and PDE6β, similar to that of PDE2A (11) (PDB ID 3IBJ) (Figs. 2 and 4). The entire PDE2A GAF domains fit reasonably well in the PDE6 map (Fig. 4A), although the fit is improved by permitting independent orientation of the GAFa and GAFb domains (Fig. 4B). The difference in relative orientations between the GAF domains in PDE2A and PDE6 is highlighted in Fig. 6. These results are contrary to previously published PDE6 GAF domain orientations based on a low resolution map (14), but in good agreement with a recently published model of PDE6 (64). The location of the non-catalytic cGMP binding site, inferred from the fitting of the cone PDE6C GAFa/cGMP crystal structure (9) (PDB ID 3DBA), is shown in Fig. 4C.

FIGURE 4.

Orientation of the GAF domains. A, comparison of the PDE2A (PDB 3IBJ (11)) and PDE6·ROS-1-Fab structures. Left, the PDE6 C2 model shown with fitting of the intact PDE2A GAF domains (purple). Right, x-ray structure of PDE2A at 11 Å with GAF domain sequences also shown as ribbons (purple). B, independent fitting of GAFa domains from chicken cone PDE6C (PDB 3DBA (9)) (orange, blue) and GAFb domains from PDE2A (cyan, green). C, alignment of GAFa domain structures from PDE2A (pink) and PDE6C (orange) crystals, showing the location of the non-catalytic cGMP binding site in PDE6C (blue).

FIGURE 6.

Comparison of PDE6 and PDE2A domain organization. The PDE6αβ atomic model is composed of the GAFa domain from chicken cone PDE6C (PDB 3DBA (9)), GAFb domain from PDE2A (PDB 3IBJ (11)), and catalytic domain from PDE5/6 (PDB 3JWR (10)), fit as in Figs. 3 and 4. Selected homologous sequences are marked in matching colors to guide the eye. The approximate changes in relative orientation between the catalytic and GAFa domains, relative to GAFb, are indicated.

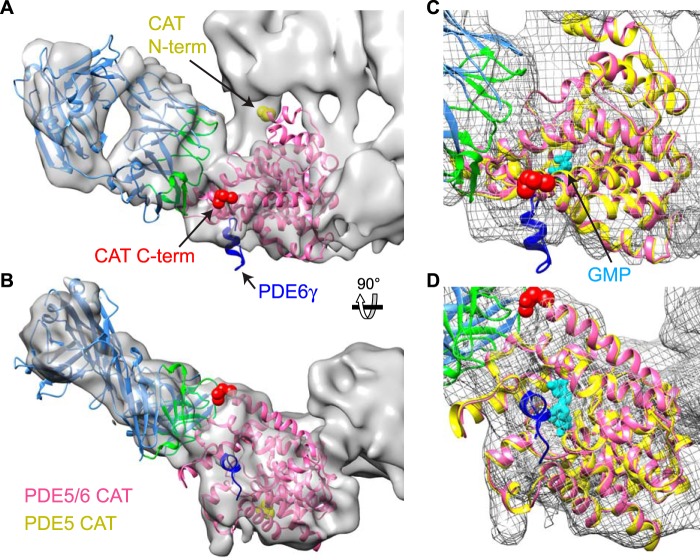

The catalytic domain contains fewer features to guide the fitting, and the orientation is therefore subject to more uncertainty. Nevertheless, when constrained so that the N-terminal residues of the catalytic domain (yellow spheres, Fig. 5, A and B) are close to the GAFb domain, as needed for continuity, a satisfactory fit was obtained. The most C-terminal residues (red spheres, Fig. 5, A and B), which lead to the membrane-binding C-terminal isoprenylated peptides, are positioned near the base of the structure. Fitting the PDE5/6 chimeric catalytic domain crystal structure (PDB ID 3JWR), which contains 17 residues of PDE6γ (10), in this orientation places the PDE6γ C terminus near the ROS-1 binding site (Fig. 5, A and B), consistent with the γ-subunit-dependent binding of the ROS-1 mAb (29). Alignment with the PDE5A catalytic domain/GMP structure (8) (PDB ID 1T9S) (Fig. 5, C and D) shows the active site with bound product, GMP (cyan), facing away from the GAF domains and toward the base, facing solvent at the enzyme surface. The difference in relative orientation of the catalytic domains in PDE6 and PDE2A is shown in Fig. 6. Although this striking difference in arrangements is surprising, given the nearly identical folds of the PDE6 and PDE2 catalytic domains, it is supported by a recently published comprehensive model of PDE6 constrained by cross-linking and mass spectrometry (64).

FIGURE 5.

Orientation of the catalytic domain. Front (A and C) and bottom (B and D) views of the PDE6·ROS-1-Fab map with fitting of catalytic domain crystal structures. A and B, the PDE5/6 chimera structure (PDB 3JWR (10)) is shown as a pink ribbon, with the N terminus (yellow spheres), C terminus (red spheres), and the PDE6γ-(71–87) peptide (blue) indicated. The Fab structure is as in Fig. 3. C and D, enlarged view of the catalytic domain, with the crystal structures of the PDE5/6 chimera (pink) and PDE5A/GMP (PDB 1T9S (8)) (yellow) aligned. GMP is shown in cyan.

PDE6·PrBP/δ Structure

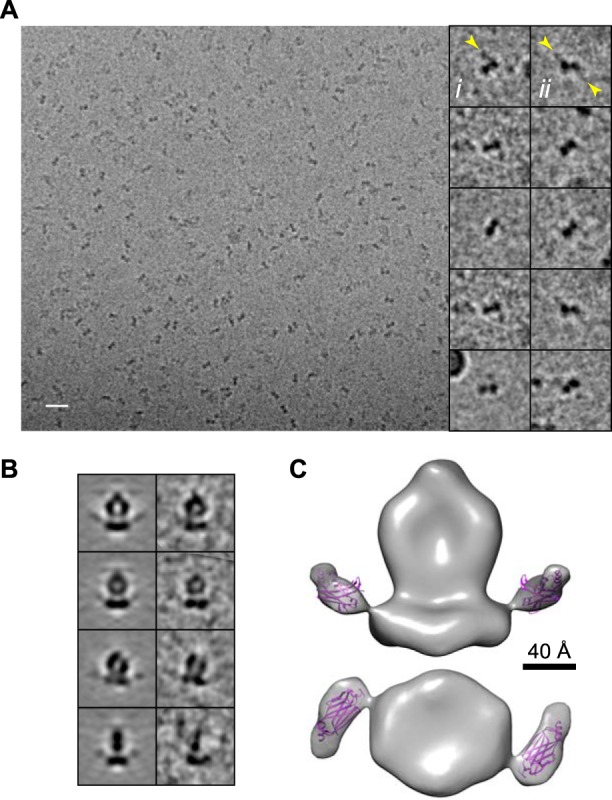

PrBP/δ is a 17.5-kDa protein that binds to the farnesyl and geranylgeranyl modifications at the C terminus of PDE6α and PDE6β, respectively (43–45). To obtain a structure of PrBP/δ-bound PDE6, complexes were imaged in vitreous ice. Visual inspection of micrographs revealed a heterogeneous mixture of particles that appeared to contain 0 (∼35%), 1 (∼40%), or 2 (∼25%) bound PrBP/δ molecules. Examples of single particles with one or two bound PrBP/δ are shown in Fig. 7A, i and ii, respectively. 3523 particles with either single or double occupancy of the PrBP/δ binding sites were used for reconstruction with C2 symmetry imposed (Fig. 7, B and C). The structure is similar to the low resolution map of PDE6, with extra mass near the base, consistent with previous evidence from projection maps (14). The crystal structure of PrBP/δ (46) fits well into the extra mass. The PrBP/δ binding site is in good agreement with the modeled locations of the PDE6α/β C termini (compare Figs. 5 and 7C), further supporting our fitting of the catalytic domain.

FIGURE 7.

Three-dimensional structure of PDE6·PrBP/δ. A, left, a typical field of PDE6·PrBP/δ complexes suspended in vitreous ice. Scale bar, 200 Å. Right, gallery of individual particles in top/bottom view orientation, with one (i) or two (ii) PrBP/δ bound (yellow arrows). B, comparison of class averages (right) and corresponding projections (left) of the final model. C, front and bottom views of the three-dimensional model of PDE6·PrBP/δ low-pass filtered to 30 Å. Scale bar, 40 Å. The crystal structure of PrBP/δ (purple; PDB ID 1KSH (46)) was fit into the extra mass at the base of the catalytic domain.

Disposition of PDE6γ Subunits

To identify the locations of the N and C termini of PDE6γ, PDE6 with the γ subunit removed by limited trypsin digestion (tPDE6) was reconstituted with recombinant PDE6γ tagged with HA epitopes at the N or C terminus. Complexes with a Fab fragment from a monoclonal antibody specific for the HA epitope were imaged (Fig. 8A). Significant heterogeneity was observed, particularly with the N-terminal tag, presumably either because of the flexible linker between the HA tag and PDEγ or because the N terminus is not always associated with PDE6αβ. The reconstructions shown represent the majority populations. The results reveal added mass of the correct size and shape for an Fab fragment at the “top” of the structure, i.e. near the GAFa domain, for the N-terminal epitope tag, and near the catalytic domain for the C-terminal tag, consistent with previous cross-linking results (20, 27, 64). The distance between the two HA-Fab binding sites is ∼90 Å (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8.

Localization of the N- and C terminus of PDE6γ. A, reconstructions of tPDE6 reconstituted with HA-PDE6γ or PDE6γ-HA and complexed with HA-Fab. Ribbon diagrams of an Fab structure (PDB 12E8 (62)) are shown in purple. B, the distance between the HA epitopes in PDE6 reconstituted with HA-PDE6γ and PDE6γ-HA was estimated by superimposing the two maps.

Effect of PDE6γ on PDE6 Structure

Removal of PDE6γ by limited trypsin digestion had a dramatic effect on PDE6 structure (Fig. 9). The bell-like particles characteristic of PDE6 front views were largely absent, with most particles (∼80%) appearing donut-like in projection (Fig. 9A). Removal of PDE6γ also introduced significant conformational heterogeneity. Using the EMAN (35) Multirefine routine with three starting models yielded three similarly populated conformations (Fig. 9D), potentially representing a range of dynamically interchangeable conformations that may well include more than three different states. To further confirm the structural rearrangement of tPDE6, an independent map was constructed by single particle tomography (47, 48) using 120 sub-volumes from tomograms of negatively stained samples (Fig. 9E). The overall features of the models generated from standard single particle procedures and single-particle tomography are similar.

FIGURE 9.

Reversible conformational change in PDE6 upon removal of PDE6γ. A, example field and single particle gallery of tPDE6 imaged in negative stain. Scale bar, 200 Å. Examples of bell- and donut-shaped particles are indicated by circles and squares, respectively. B, class averages of tPDE6 and PDE6 or tPDE6 in the presence of excess recombinant PDE6γ. C, Coomassie-stained gel of PDE6 before and after trypsin treatment and reconstituted with recombinant PDE6γ. D, single particle Multirefine procedure starting with ∼4100 particles and three initial models yielded three similarly populated subsets of particles. The models (with C2 symmetry imposed) were low-pass filtered to 30 Å and are shown in three orthogonal views. E, C1 and C2 maps constructed by single particle tomography using 120 sub-volumes are shown in the same orientations as in D. F, comparison of PDE6 and tPDE6 maps from samples in negative stain. Three-dimensional maps (with C2 symmetry) are shown in an isosurface representation with the contour level approximating the PDE6 and tPDE6 molecular mass of 220 and 200 kDa, respectively. The atomic model of PDE6αβ, as shown in Fig. 6, is docked into the PDE6 map. The tPDE6 map is shown with a speculative rearrangement of the domains.

In addition to removal of PDE6γ, trypsin treatment also results in cleavage of the catalytic subunits near the C terminus (49). However, the structural rearrangement was reversed upon reconstitution of tPDE6 with recombinant PDE6γ (Fig. 9B), confirming that it is in fact the PDE6γ polypeptide that is essential for conformational stability of PDE6.

DISCUSSION

Imaging of PDE6·ROS-1-Fab complexes in ice has provided greater structural detail than previously available, permitting fitting of all three catalytic subunit domains with reasonable confidence (see Figs. 2–6). The resulting orientation of domains is significantly different from that reported previously (14). The most striking feature of the new higher resolution map is the long dimer interface, which was not discernible in low resolution structures (12–14). Whereas the overall domain organizations of PDE6αβ and PDE2A are similar, the relative positions of the domains are different (see Fig. 6). Although catalytic domains are conserved and structurally similar among PDE family members, their orientation with respect to GAF domains appears to be variable. The catalytic domains of PDE6 and PDE2A are in strikingly different orientations, possibly reflecting the different modes of regulation of the enzymatic activity. In the full-length PDE2A crystal the two catalytic domains are oriented such that the two substrate binding sites occlude each other at the dimer interface, and it was proposed that cGMP binding to the GAFb domain causes the catalytic domains to move apart (11). In contrast, the PDE6 catalytic site is occluded by PDE6γ; sequestration of the PDE6γ C terminus by Gαt is required for activation (10, 15–18).

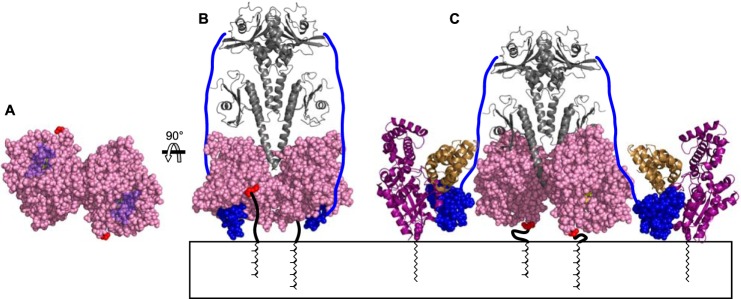

The precise orientation of PDE6 with respect to the membrane is unknown; a proposed model is shown in Fig. 10. Both the PrBP/δ binding sites (see Fig. 7) and the catalytic domain fitting (see Fig. 5) place the membrane-anchoring prenyl chains of PDE6α and -β near the outer edge of the catalytic domains. This location, far away from the long axis of the catalytic domain region, suggests that PDE6 maintains a relatively upright orientation (Fig. 10, A and B). The catalytic domain fitting suggests that the catalytic cGMP binding site and the C terminus of PDE6γ are at the “bottom” face of the molecule (Fig. 10A, see Fig. 5). An active site location near the membrane surface fits well with biochemical studies of PDE6 activation by Gαt; efficient activation requires that both the activated Gαt subunit and PDE6 have intact lipidated membrane binding regions and requires a membrane surface on which they interact (50, 51). Moreover, the nature of the phospholipids forming the surface has a strong effect on the efficiency of activation (50–55). However, the fact that PDE6 is easily eluted from ROS membranes in hypotonic conditions (3, 28) indicates that the catalytic domains probably do not make extensive interactions with the lipid bilayer. Rather, the membrane may enhance PDE6 activation by favoring the optimal interaction between PDE6 and Gαt and/or the correct PDE6 conformational change.

FIGURE 10.

Model of PDE6 membrane interaction. A and B, PDE6 model as described in Fig. 6. The C-terminal residue in the catalytic domain structure is shown in red, and the PDE6γ-(71–87) peptide in blue. A, bottom view with PDE6γ rendered transparent to reveal the inhibitor 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (yellow) bound in the active site. B, front view with diagram of the C-terminal residues not present in the catalytic domain crystal (thick black line) and attached farnesyl and geranylgeranyl groups. The remainder of PDE6γ (residues 1–70) is drawn as a blue line. C, proposed model of PDE6 activation. Catalytic domains are rotated 90 ° in opposite directions, about their N termini, to expose the catalytic sites. PDE6γ-(50–87) is shown in the crystal structure of the complex with Gαt (purple) and an RGS-9 fragment (brown) (PDB 1FQJ (5)).

To allow Gαt access to the PDE6γ C terminus and exposure of the active site, a change in orientation with respect to the membrane may be necessary. Both PDE6α and -β have ∼40 additional amino acids C-terminal to the region homologous with the PDE5/6 chimera construct (10) used for fitting. It is therefore possible, despite the location of the prenyl chains in the PDE6·PrBP/δ structure (see Fig. 7), that stretching out of one of these C termini could allow the entire enzyme to tilt to one side while still keeping both prenyl chains in the membrane. We also propose an alternative possible mechanism whereby the catalytic domains rotate in opposite directions such that both PDE6α and -β C termini approach the membrane and the active sites become accessible (Fig. 10C). PDE6γ regions that do not interact with Gαt can potentially stabilize the domain arrangement through contacts with both the catalytic domains and the GAFa domain (20, 27, 56, 64) (see Fig. 8).

The arrangement of domains is likely to be dynamic. For example, there is a significant difference in the relative orientations of the GAFa and GAFb domains of PDE2A in unliganded and nucleotide-bound states (11, 57). Dynamic arrangement is also suggested by the severe but reversible reorganization observed upon removal of PDE6γ by limited trypsin digest (see Fig. 9). Although the tPDE6 structure demonstrates the ability of PDE6 to undergo dramatic reversible domain rearrangements, its physiological relevance is unknown. Trypsinization of PDE6 causes degradation and/or dissociation of the entire PDE6γ peptide (58). In contrast, when activated by transducin, PDE6γ is displaced from the active site but may remain bound to the complex (50, 51, 56, 59, 60). In addition, the C-terminal cleavages of PDE6α and -β caused by trypsin (49), although not sufficient for the rearrangement, may contribute to structural instability. Regardless, the apparently normal structure of tPDE6 reconstituted with recombinant PDE6γ supports the use of this model system in structural studies, such as in the HA-Fab labeling experiments.

Our data place the PDE6γ C terminus at the catalytic domain, as expected, and the N terminus near the GAFa domain (see Fig. 8). In addition to its role in inhibiting enzyme activity at the catalytic domain, PDE6γ also participates in reciprocal regulation of cGMP binding to the non-catalytic sites in the GAF domains. Binding of PDE6γ enhances the affinity for cGMP at the non-catalytic sites, and binding of cGMP to the GAF domains in turn increases the affinity of the catalytic domains for PDE6γ (22–25). It has been proposed on the basis of cross-linking, mutagenesis, and genetic studies that the N-terminal region of PDE6γ binds directly to one or both of the GAFa domains of PDE6αβ (20, 27, 61, 64). Our data provide direct structural evidence supporting this type of interaction for both copies of PDE6γ in the holoenzyme.

In the crystal structure of a C-terminal fragment of PDE6γ bound to activated transducin (5), residues 50–87, comprising almost half of the molecule, assume a compact globular structure in its complex with activated G protein and RGS protein. Biochemical evidence indicates that these proteins and PDE6αβ bind PDE6γ simultaneously (56, 60), so this compact structure is likely compatible with tight binding to PDE6αβ. In this scenario, nearly the entire N-terminal half of the molecule must adopt an extended chain conformation to reach from the catalytic base of PDE6 to the GAFa domains. Even if only the structured part of PDE6γ (residues 76–87) visible in its complex with the catalytic fragment of the PDE5/6 chimera (10) is globular in the native heterotetramer, the remainder of PDE6γ would still have to adopt a largely extended conformation to reach the GAFa domain.

The results presented here allow the wealth of biochemical data about PDE6 and the related PDE5 isozymes to be placed in the context of a three-dimensional structure. The structural models presented pose many hypotheses about structure-function relationships that can now be addressed by combining biochemical and mutagenesis studies with further cryo-EM studies using site-specific labels.

Acknowledgments

We thank Justine Malinski for initiating this project. We thank Steven Ludtke, Donghua Chen, and the personnel of the National Center for Macromolecular Imaging for advice and technical assistance. Molecular graphics images were produced using the UCSF CHIMERA package from the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco (supported by National Institutes of Health Grants P41-RR001081 and P41-GM103311).

Note Added in Proof

References 63 and 64 and the accompanying text were not included in the version of this article that was published on March 25, 2015, as a Paper in Press. This error has been corrected.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-EY07981 (to T. G. W.), R01-EY008123 (to W. B.), P41-GM103832, and P41-RR002250. This work was also supported by the Welch Foundation, Q-0035.

The map of PDE6·ROS-1-Fab has been deposited in the EMDataBank with accession code EMD-6258.

J. A. Malinski and T. G. Wensel, unpublished observations.

- PDE

- phosphodiesterase

- tPDE6

- trypsinized PDE6

- ROS

- rod outer segment

- FSC

- Fourier shell correlation

- PrBP

- prenyl-binding protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Conti M., Beavo J. (2007) Biochemistry and physiology of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: essential components in cyclic nucleotide signaling. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76, 481–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Francis S. H., Turko I. V., Corbin J. D. (2001) Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: relating structure and function. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 65, 1–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baehr W., Devlin M. J., Applebury M. L. (1979) Isolation and characterization of cGMP phosphodiesterase from bovine rod outer segments. J. Biol. Chem. 254, 11669–11677 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Deterre P., Bigay J., Forquet F., Robert M., Chabre M. (1988) cGMP phosphodiesterase of retinal rods is regulated by two inhibitory subunits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 2424–2428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Slep K. C., Kercher M. A., He W., Cowan C. W., Wensel T. G., Sigler P. B. (2001) Structural determinants for regulation of phosphodiesterase by a G protein at 2.0 Å. Nature 409, 1071–1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Card G. L., England B. P., Suzuki Y., Fong D., Powell B., Lee B., Luu C., Tabrizizad M., Gillette S., Ibrahim P. N., Artis D. R., Bollag G., Milburn M.V., Kim S. H., Schlessinger J., Zhang K. Y. (2004) Structural basis for the activity of drugs that inhibit phosphodiesterases. Structure 12, 2233–2247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Huai Q., Liu Y., Francis S. H., Corbin J. D., Ke H. (2004) Crystal structures of phosphodiesterases 4 and 5 in complex with inhibitor 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine suggest a conformation determinant of inhibitor selectivity. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 13095–13101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhang K. Y., Card G. L., Suzuki Y., Artis D. R., Fong D., Gillette S., Hsieh D., Neiman J., West B. L., Zhang C., Milburn M. V., Kim S. H., Schlessinger J., Bollag G. (2004) A glutamine switch mechanism for nucleotide selectivity by phosphodiesterases. Mol. Cell 15, 279–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Martinez S. E., Heikaus C. C., Klevit R. E., Beavo J. A. (2008) The structure of the GAF A domain from phosphodiesterase 6C reveals determinants of cGMP binding, a conserved binding surface, and a large cGMP-dependent conformational change. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 25913–25919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barren B., Gakhar L., Muradov H., Boyd K. K., Ramaswamy S., Artemyev N. O. (2009) Structural basis of phosphodiesterase 6 inhibition by the C-terminal region of the γ-subunit. EMBO J. 28, 3613–3622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pandit J., Forman M. D., Fennell K. F., Dillman K. S., Menniti F. S. (2009) Mechanism for the allosteric regulation of phosphodiesterase 2A deduced from the x-ray structure of a near full-length construct. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 18225–18230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kameni Tcheudji J. F., Lebeau L., Virmaux N., Maftei C. G., Cote R. H., Lugnier C., Schultz P. (2001) Molecular organization of bovine rod cGMP-phosphodiesterase 6. J. Mol. Biol. 310, 781–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kajimura N., Yamazaki M., Morikawa K., Yamazaki A., Mayanagi K. (2002) Three-dimensional structure of non-activated cGMP phosphodiesterase 6 and comparison of its image with those of activated forms. J. Struct. Biol. 139, 27–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goc A., Chami M., Lodowski D. T., Bosshart P., Moiseenkova-Bell V., Baehr W., Engel A., Palczewski K. (2010) Structural characterization of the rod cGMP phosphodiesterase 6. J. Mol. Biol. 401, 363–373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lipkin V. M., Dumler I. L., Muradov K. G., Artemyev N. O., Etingof R. N. (1988) Active sites of the cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase γ-subunit of retinal rod outer segments. FEBS Lett. 234, 287–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brown R. L. (1992) Functional regions of the inhibitory subunit of retinal rod cGMP phosphodiesterase identified by site-specific mutagenesis and fluorescence spectroscopy. Biochemistry 31, 5918–5925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Skiba N. P., Artemyev N. O., Hamm H. E. (1995) The carboxyl terminus of the γ-subunit of rod cGMP phosphodiesterase contains distinct sites of interaction with the enzyme catalytic subunits and the α-subunit of transducin. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 13210–13215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Granovsky A. E., Natochin M., Artemyev N. O. (1997) The γ subunit of rod cGMP-phosphodiesterase blocks the enzyme catalytic site. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 11686–11689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Granovsky A. E., Artemyev N. O. (2000) Identification of the γ subunit-interacting residues on photoreceptor cGMP phosphodiesterase, PDE6α′. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 41258–41262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guo L.-W., Muradov H., Hajipour A. R., Sievert M. K., Artemyev N. O., Ruoho A. E. (2006) The inhibitory γ subunit of the rod cGMP phosphodiesterase binds the catalytic subunits in an extended linear structure. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 15412–15422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wensel T. G., Stryer L. (1986) Reciprocal control of retinal rod cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase by its γ subunit and transducin. Proteins 1, 90–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Arshavsky V. Y., Dumke C. L., Bownds M. D. (1992) Noncatalytic cGMP-binding sites of amphibian rod cGMP phosphodiesterase control interaction with its inhibitory y-subunits: a putative regulatory mechanism of the rod photoresponse. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 24501–24507 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Norton A. W., D'Amours M. R., Grazio H. J., Hebert T. L., Cote R. H. (2000) Mechanism of transducin activation of frog rod photoreceptor phosphodiesterase: allosteric interactions between the inhibitory γ subunit and the noncatalytic cGMP-binding sites. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 38611–38619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mou H., Cote R. H. (2001) The catalytic and GAF domains of the rod cGMP phosphodiesterase (PDE6) heterodimer are regulated by distinct regions of its inhibitory γ subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 27527–27534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yamazaki M., Li N., Bondarenko V. A., Yamazaki R. K., Baehr W., Yamazaki A. (2002) Binding of cGMP to GAF domains in amphibian rod photoreceptor cGMP phosphodiesterase (PDE): identification of GAF domains in PDE αβ subunits and distinct domains in the PDE γ subunit involved in stimulation of cGMP binding to GAF domains. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 40675–40686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huang D., Hinds T. R., Martinez S. E., Doneanu C., Beavo J. A. (2004) Molecular determinants of cGMP binding to chicken cone photoreceptor phosphodiesterase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 48143–48151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Muradov K. G., Granovsky A. E., Schey K. L., Artemyev N. O. (2002) Direct interaction of the inhibitory γ-subunit of rod cGMP phosphodiesterase (PDE6) with the PDE6 GAFa domains. Biochemistry 41, 3884–3890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wensel T. G., He F., Malinski J. A. (2005) Purification, reconstitution on lipid vesicles, and assays of PDE6 and its activator G protein, transducin. Methods Mol. Biol. 307, 289–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hurwitz R. L., Bunt-Milam A. H., Beavo J. A. (1984) Immunologic characterization of the photoreceptor outer segment cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 8612–8618 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brown R. L., Stryer L. (1989) Expression in bacteria of functional inhibitory subunit of retinal rod cGMP phosphodiesterase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 4922–4926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. He W., Cowan C. W., Wensel T. G. (1998) RGS9, a GTPase accelerator for phototransduction. Neuron 20, 95–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liebman P. A., Pugh E. N., Jr. (1982) Gain, speed, and sensitivity of GTP binding vs PDE activation in visual excitation. Vision Res. 22, 1475–1480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cote R. H. (2005) Cyclic guanosine 5′-monophosphate binding to regulatory GAF domains of photoreceptor phosphodiesterase. Methods Mol. Biol. 307, 141–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mastronarde D. N. (2005) Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J. Struct. Biol. 152, 36–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ludtke S. J., Baldwin P. R., Chiu W. (1999) EMAN: semiautomated software for high-resolution single-particle reconstructions. J. Struct. Biol. 128, 82–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mastronarde D. N. (1997) Dual-axis tomography: an approach with alignment methods that preserve resolution. J. Struct. Biol. 120, 343–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., Ferrin T. E. (2004) UCSF Chimera: a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jiang W., Baker M. L., Ludtke S. J., Chiu W. (2001) Bridging the information gap: computational tools for intermediate resolution structure interpretation. J. Mol. Biol. 308, 1033–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hurwitz R. L., Beavo J. A. (1984) Immunotitration analysis of the rod outer segment phosphodiesterase. Adv. Cyclic Nucleotide Protein Phosphorylation Res. 17, 239–248 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lee R. H., Lieberman B. S., Hurwitz R. L., Lolley R. N. (1985) Phosphodiesterase-probes show distinct defects in rd mice and Irish setter dog disorders. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 26, 1569–1579 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kolandaivelu S., Huang J., Hurley J. B., Ramamurthy V. (2009) AIPL1, a protein associated with childhood blindness, interacts with α-subunit of rod phosphodiesterase (PDE6) and is essential for its proper assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 30853–30861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rosenthal P. B., Henderson R. (2003) Optimal determination of particle orientation, absolute hand, and contrast loss in single-particle electron cryomicroscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 333, 721–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Anant J. S., Ong O. C., Xie H. Y., Clarke S., O'Brien P. J., Fung B. K. (1992) In vivo differential prenylation of retinal cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase catalytic subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 687–690 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cook T. A., Ghomashchi F., Gelb M. H., Florio S. K., Beavo J. A. (2000) Binding of the delta subunit to rod phosphodiesterase catalytic subunits requires methylated, prenylated C-termini of the catalytic subunits. Biochemistry 39, 13516–13523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhang H., Liu X. H., Zhang K., Chen C.-K., Frederick J. M., Prestwich G. D., Baehr W. (2004) Photoreceptor cGMP phosphodiesterase δ subunit (PDEδ) functions as a prenyl-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 407–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hanzal-Bayer M., Renault L., Roversi P., Wittinghofer A., Hillig R. C. (2002) The complex of Arl2-GTP and PDEδ: from structure to function. EMBO J. 21, 2095–2106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Walz J., Typke D., Nitsch M., Koster A. J., Hegerl R., Baumeister W. (1997) Electron tomography of single ice-embedded macromolecules: three-dimensional alignment and classification. J. Struct. Biol. 120, 387–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schmid M. F., Booth C. R. (2008) Methods for aligning and for averaging 3D volumes with missing data. J. Struct. Biol. 161, 243–248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Catty P., Deterre P. (1991) Activation and solubilization of the retinal cGMP-specific phosphodiesterase by limited proteolysis. Eur. J. Biochem. 199, 263–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Malinski J. A., Wensel T. G. (1992) Membrane stimulation of cGMP phosphodiesterase activation by transducin: Comparison of phospholipid bilayers to rod outer segment membranes. Biochemistry 31, 9502–9512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Melia T. J., Malinski J. A., He F., Wensel T. G. (2000) Enhancement of phototransduction protein interactions by lipid surfaces. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 3535–3542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Miller J. L., Litman B. J., Dratz E. A. (1987) Binding and activation of rod outer segment phoshodiesterase and guanosine triphosphate binding protein by disc membranes: influence of reassociation method and divalent cations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 898, 81–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Litman B. J., Niu S.-L., Polozova A., Mitchell D. C. (2001) The role of docosahexaenoic acid containing phospholipids in modulating G protein-coupled signaling pathways. J. Mol. Neurosci. 16, 237–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mitchell D. C., Niu S.-L., Litman B. J. (2003) DHA-rich phospholipids optimize G-protein-coupled signaling. J. Pediatr. 143, S80–S86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. He F., Mao M., Wensel T. G. (2004) Enhancement of phototransduction G protein-effector interactions by phosphoinositides. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 8986–8990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Guo L.-W., Hajipour A. R., Ruoho A. E. (2010) Complementary interactions of the rod PDE6 inhibitory subunit with the catalytic subunits and transducin. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 15209–15219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Martinez S. E., Wu A. Y., Glavas N. A., Tang X.-B., Turley S., Hol W. G., Beavo J. A. (2002) The two GAF domains in phosphodiesterase 2A have distinct roles in dimerization and in cGMP binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 13260–13265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hurley J. B., Stryer L. (1982) Purification and characterization of the y regulatory subunit of the cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase from retinal rod outer segments. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 11094–11099 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Catty P., Pfister C., Bruckert F., Deterre P. (1992) The cGMP phosphodiesterase-transducin complex of retinal rods. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 19489–19493 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sitaramayya A., Harkness J., Parkes J. H., Gonzalez-Oliva C., Liebman P. A. (1986) Kinetic studies suggest that light-activated cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase is a complex with G-protein subunits. Biochemistry 25, 651–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gal A., Orth U., Baehr W., Schwinger E., Rosenberg T. (1994) Heterozygous missense mutation in the rod cGMP phosphodiesterase β-subunit gene in autosomal dominant stationary night blindness. Nat. Genet. 7, 64–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Trakhanov S., Parkin S., Raffaï R., Milne R., Newhouse Y. M., Weisgraber K. H., Rupp B. (1999) Structure of a monoclonal 2E8 Fab antibody fragment specific for the low-density lipoprotein-receptor binding region of apolipoprotein E refined at 1.9 Å. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55, 122–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zhang X. J., Skiba N. P., Cote R. H. (2010) Structural requirements of the photoreceptor phosphodiesterase γ-subunit for inhibition of rod PDE6 holoenzyme and for its activation by transducin. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 4455–4463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zeng-Elmore X., Gao X. Z., Pellarin R., Schneidman-Duhovny D., Zhang X. J., Kozacka K. A., Tang Y., Sali A., Chalkley R. J., Cote R. H., Chu F. (2014) Molecular architecture of photoreceptor phosphodiesterase elucidated by chemical cross-linking and integrative modeling. J. Mol. Biol. 426, 3713–3728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]