Abstract

A 76-year-old woman with compression fracture of L1 underwent percutaneous balloon kyphoplasty using polymethyl methacrylate. Three years after kyphoplasty of L1, the patient was readmitted with severe low back pain. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed progressive collapse of L1 vertebra and new compression fracture at T12. There were no signs of infection. As conservative treatment failed, combined surgery consisting of anterior corpectomy of T12 and L1, interposition of a titanium mesh cage filled with autologous rib graft, and anterior instrumentation of T11-L2 was performed. Histologic examination showed granulomatous inflammation surrounding the cement. Polymerase chain reaction and culture of the specimen confirmed the diagnosis of tuberculosis. The anti-tuberculous medications were administered for 10 months, and the patient recovered without any sequelae. Tuberculous spondylitis should be included in the differential diagnosis of spondylitis after cement augmentation. If conservative antibiotic therapy fails, resection of the infected bone-cement complex is indicated.

Keywords: Cementoplasty, Vertebroplasty, Kyphoplasty, Complications, Infection, Spinal tuberculosis

INTRODUCTION

Percutaneous kyphoplasty has been proved to be effective in the treatment of osteoporotic compression fractures7,11,12). Itinvolves balloon inflation and injection of polymethyl methacrylate into the fractured vertebra. It can dramatically relieve pain and may restore height of vertebral body7,11,12). Although the complication rate is low, many complications including cement leakage, emboli to the brain, lung and heart, intraoperative rib fractures, and subsequent fractures of the adjacent or augmented vertebrae have been reported in the recent literature4,14). However, infectious complications after cement augmentation are still rarely reported2,8,13,16,17). Tuberculous infections are even more rare, and to the best of our knowledge, only 2 cases of tuberculous spondylitis after cement augmentation have been reported3,10). Here we report a case of tuberculous spondylitis after kyphoplasty and its successful management with a review of the literature.

CASE REPORT

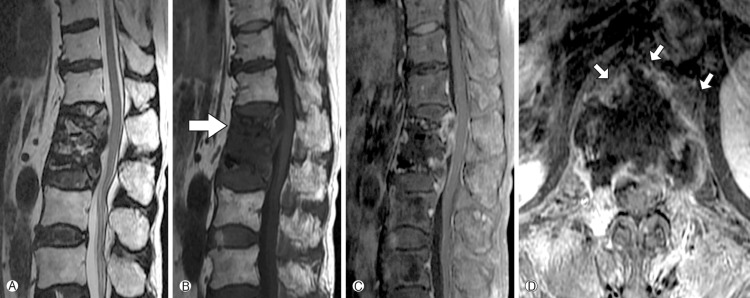

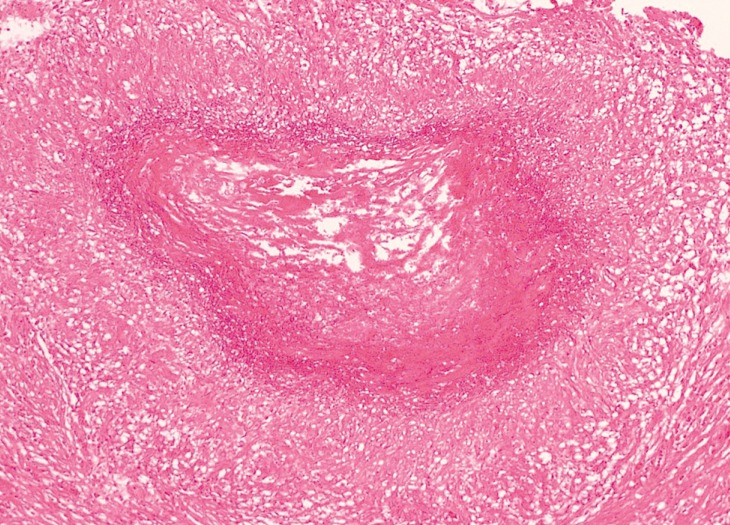

A 76-year-old woman visited our clinic for severe low back pain recently aggravated without any predisposing factor. The patient had a medical history of type II diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Simple radiographs of the lumbar spine showed a compression fracture of L1. Mag- netic resonance imaging (MRI) scan revealed a benign compression fracture of L1. The patient was admitted to our department for kyphoplasty of L1. Blood pressure was maintained within the normal range and blood sugar level was well regulated. T-score for bone densitometry was calculated to be -4.3. Chest radiographs did not show any signs of pulmonary disease. Percutaneous kyphoplasty was performed under local anesthesia without any complications. The severe low back pain disappeared immediately after kyphoplasty. Three years later, the patient presented to the pain clinic complaining of recurrent low back pain. The patient underwent lumbar epidural block and facet joint block. Several days later, the patient returned to our department due to aggravation of low back pain and development of fever. Laboratory tests revealed elevated inflammatory markers, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin levels. Empirical broad-spectrum antibiotics were administered. MRI scan was conducted and showed new compression fracture at T12, paravertebral abscess, and spondylitis of T12 and L1 (Fig. 1). We suspected bacterial spondylitis, as there was no typical evidence of tuberculous spondylitis including commencement of infection at the anterior aspect of the vertebral body adjacent to the endplate. The patient did not respond to antibiotic treatment and there was no decrease in inflammatory markers. The patient complained of intolerable lower back pain and radiating leg pain. We performed surgery for tissue biopsy, pathogen identification and spinal decompression. Total corpectomy of T12 and L1 was performed using a transdiaphragmatic retropleural-retroperitoneal approach. Then anterior reinforcement with a titanium mesh cage filled with autologous rib graft was performed. The necrotic tissue was biopsied and cultured. However, the bacterial culture was negative. Histologic examination of the resected specimen revealed a granulomatous inflammation with caseous necrosis (Fig. 2). Therefore, specific polymerase chain reaction and acid-fast bacilli stain were subsequently carried out and they confirmed the diagnosis of a tuberculous infection. Subsequent tuberculosis culture showed evidence for mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antibiotics were promptly changed to anti-tuberculous medications including isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. Approximately three months after the surgery and anti-tuberculous medications, inflammatory markers decreased to subclinical levels. The anti-tuberculous medications were administered for 10 months, and the patient recovered without any sequelae.

Fig. 1. Magnetic resonance images (A: T2-weighted images, B: T1-weighted images, C: Enhanced sagittal T1-weighted images, D: Enhanced axial T1-weighted images). They demonstrate progressive collapse of the previously augmented L1 vertebra. They also demonstrate a new compression fracture at T12 (large arrow), paravertebral abscess, and spondylitis of T12 and L1 (small arrow).

Fig. 2. Histologic examination of the resected infected tissue shows chronic granulomatous inflammation with caseous necrosis consistent with tuberculosis (H&E staining, ×100).

DISCUSSION

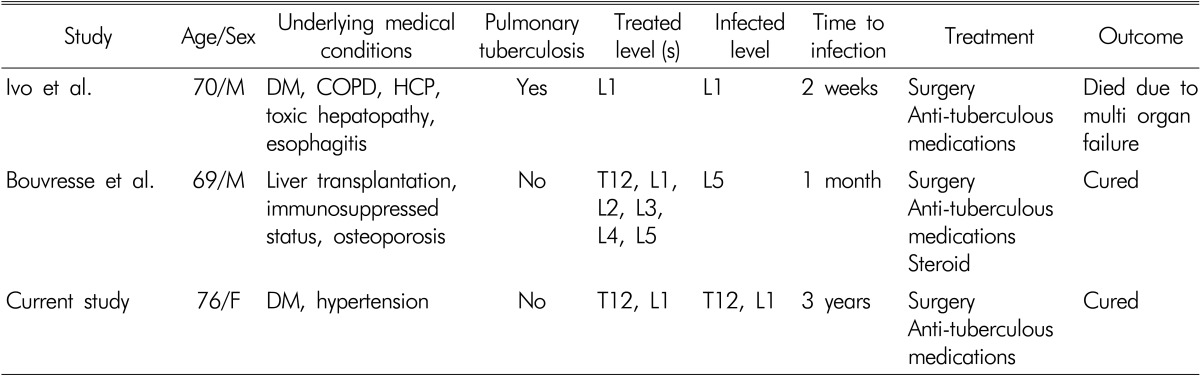

There are several reports of episodes of serious local infections after cement augmentation in patients with any history ofsystemic infection13,16). Reports of cases of spinal tuberculosis after cement augmentation are extremely rare, with only 2 cases being reported in the literature with PubMed search (Table 1)3,10). The worldwide incidence of tuberculosis continues to increase6). Although spinal tuberculosis accounts for 2% of all tuberculosis cases, its incidence is increasing in parallel with the growing numbers of immunocompromised patients10).

Table 1. Summary of 3 cases of tuberculous spondylitis after cement augmentation.

DM: diabetes mellitus, COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, HCP: hypertensive cardiomyopathy

The occurrence of tuberculous spondylitis can be explained in several ways. In case of active pulmonary tuberculosis, hematogenous spreading from the lung to the vertebra is the most probable mechanism10). As cultures of bronchial washings confirmed the diagnosis of tuberculosis, the case reported by Ivo can be explained to have been caused by hematogenous spreading10). However, the present case and the case reported by Bouvresse showed no evidence of active pulmonary tuberculosis3). Since in most of the cases reported in the literature, the patients did not suffer from pulmonary tuberculosis, local reacti- vation of quiescentmycobacteria can be suggested as another probable mechanism3,10). Mycobacteria divide asymmetrically, generating a population of cells that grow at different rates, have different sizes, and differ in how susceptible they are to antibiotics, increasing the chances that at least some will survive1). In addition, mycobacteria-infected macrophages at the primary site of infection may migrate and initiate tuberculous spondylitis3). Ivo suggested that cement augmentation may act as a trigger for serious tuberculous or nontuberculous infections by unknown mechanisms10). The term locus minoris resistentiae indicates a place of less resistance3). This concept explains why tuberculous and nontuberculous mycobacterial infections arise at the site of injury. According to this concept, cement augmentation can be considered as surgical trauma, and hence tuberculous spondylitis may develop easily. There is another possibility of tuberculous spondylitis being initially misdiag- nosed as benign compression fracture. Clinical and radiological features of tuberculous spondylitis and benign com- pression fracture are similar5). However, in our case, it is unclear whether kyphoplasty triggered a local tissue response thereby increasing susceptibility to tuberculous spondylitisor we performed kyphoplasty on an infected vertebra since the time between kyphoplasty and the occurrence of tuberculous spondylitis was more than three years. In the case of tuberculous spondylitis, the lungs are rarely involved and there are no specificsigns or symptoms9,15). Although MRI scan is currently the most accurate imaging study, it still may not differentiate betweentuberculous spondylitis and benign compression fracture in some cases5). Therefore, the diagnosis of spinal tuberculosis is difficult and often delayed. All patients cannot be diagnosed as tuberculous spondylitis preoperatively. The patient in the case reported by Ivo initially took broad spectrum antibiotics while our patient underwent conservative treatment for two months10). As the correct diagnosis and specific treatment is essential, a physician should be aware of this disease entity to avoid any delay in diagnosis and treatment. In case of presence of any risk factors for tuberculosis, adequate microbiological and histologic examination is necessary. Also, if no pathogen is cultured from tissue specimens of infective spondylitis, performing tuberculosis culture should be considered. Active investigation including microbiological and histologic examination is of utmost importance to avoid any delay in correct diagnosis and specific treatment. If medical treatment fails, the surgical resection of the infected vertebrae is recommended with careful consideration of the patient's general medical condition.

CONCLUSION

Tuberculous spondylitis should be included in the differential diagnosis of spondylitis after cement augmentation. If conservative antibiotic therapy fails, resection of the infected bone-cement complex is indicated.

References

- 1.Aldridge BB, Fernandez-Suarez M, Heller D, Ambravaneswaran V, Irimia D, Toner M, et al. Asymmetry and aging of mycobacterial cells lead to variable growth and antibiotic susceptibility. Science. 2012 doi: 10.1126/science.1216166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alfonso Olmos M, Silva Gonzalez A, Duart Clemente J, Villas Tome C. Infected vertebroplasty due to uncommon bacteriasolved surgically: A rare and threatening life complication of a common procedure: Report of a case and a review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31(20):E770–E773. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000240202.91336.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouvresse S, Chiras J, Bricaire F, Bossi P. Pott's disease occurring after percutaneous vertebroplasty: An unusual illustration of the principle of locus minoris resistentiae. J Infect. 2006;53(6):e251–e253. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burton AW, Rhines LD, Mendel E. Vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty: A comprehensive review. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;18(3):e1. doi: 10.3171/foc.2005.18.3.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Currie S, Galea-Soler S, Barron D, Chandramohan M, Groves C. Mri characteristics of tuberculous spondylitis. Clin Radiol. 2011;66(8):778–787. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dye C. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis. Lancet. 2006;367(9514):938–940. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68384-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felder-Puig R, Piso B, Guba B, Gartlehner G. [kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty for the management of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures: A systematic review] Orthopade. 2009;38(7):606–615. doi: 10.1007/s00132-009-1446-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaye M, Fuentes S, Pech-Gourg G, Benhima Y, Dufour H. [spondylitis following vertebroplasty. Case report and review of the literature] Neurochirurgie. 2008;54(4):551–555. doi: 10.1016/j.neuchi.2008.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hadadi A, Rasoulinejad M, Khashayar P, Mosavi M, Maghighi Morad M. Osteoarticular tuberculosis in tehran, iran: A 2-year study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16(8):1270–1273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ivo R, Sobottke R, Seifert H, Ortmann M, Eysel P. Tuberculous spondylitis and paravertebral abscess formation after-kyphoplasty: A case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35(12):E559–E563. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ce1aab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGirt MJ, Parker SL, Wolinsky JP, Witham TF, Bydon A, Gokaslan ZL, et al. Vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty for the treatment of vertebral compression fractures: An evidenced-based review of the literature. Spine J. 2009;9(6):501–508. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moon BG. The comparative study for clinical and radiologic results of unilateral kyphoplasty and bilateral vertebroplasty. Korean J Spine. 2010;7(4):242–248. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mummaneni PV, Walker DH, Mizuno J, Rodts GE. Infected vertebroplasty requiring 360 degrees spinal reconstruction: Long-term follow-up review. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;5(1):86–89. doi: 10.3171/spi.2006.5.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nussbaum DA, Gailloud P, Murphy K. A review of complications associated with vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty as reported to the food and drug administration medical device related web site. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;15(11):1185–1192. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000144757.14780.E0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pertuiset E. Medical therapy of bone and joint tuberculosis in 1998. Rev Rhum Engl Ed. 1999;66(3):152–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shin JH, Ha KY, Kim KW, Lee JS, Joo MW. Surgical treatment for delayed pyogenic spondylitis after percutaneous vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty. Report of 4 cases. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;9(3):265–272. doi: 10.3171/SPI/2008/9/9/265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vats HS, McKiernan FE. Infected vertebroplasty: Case report and review of literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31(22):E859–E862. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000240665.56414.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]