Abstract

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis (LYG) is a lymphoproliferative disease involving the lungs most frequently; however, it may also involve the kidneys, skin and especially the central nervous system. Unique initial presentation of spinal involvement is extremely rare and epidural lesion of thoracic spine has not been reported. The prognosis for LYG has been reported to be poor, and there currently exists no satisfactory established treatment protocol. The purpose of this study is to report a case of successful treatment with surgery and rituximab combination therapy in thoracic spinal LYG.

Keywords: Lymphomatoid granulomatosis, Epstein-Barr virus, Spine

INTRODUCTION

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis (LYG) is a rare angiocentric and angiodestructive lymphoproliferative disease with granulomatous reaction involving the lungs most frequently, However, it may also involve the kidneys, skin and especially the central nervous system4,6,9,11).

LYG is characterized by an infiltration of atypical lymphocytoid and plasmocytoid cells, with granulomatous inflammation in an angiocentric and angiodestructive polymorphic cellular infiltrate6,8). There has been only one case report of spinal involvement of LYG8). Presentation as a thoracic epidural lesion has not been reported. Therefore the purpose of this study is to submit the first report about the case with thoracic spinal LYG after diagnosis with B-precursor childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). After surgical decompression with biopsy on the spinal lesion, diagnosis of grade II LYG was made and rituximab was administered. The patient is in good neurological condition without recurrence at the 6-year follow-up.

CASE REPORT

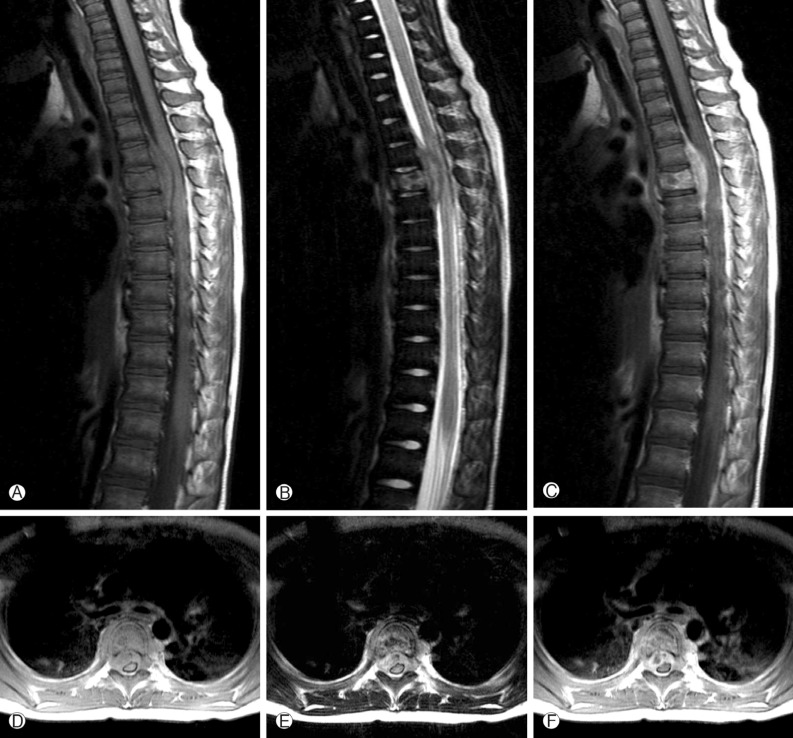

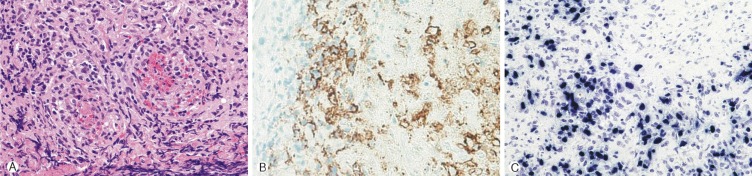

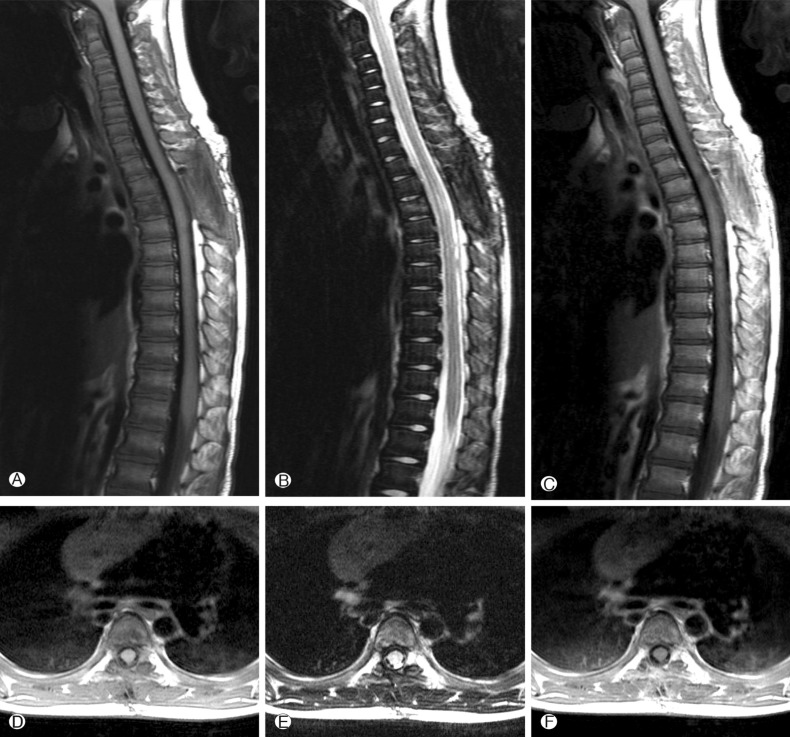

A 4-year-old girl was diagnosed with B-precursor ALL with the involvement of kidneys and pancreas in November, 2004. Treatment was initiated according to the Pediatric Oncology Group (POG) protocol 900612). On April 12, 2006, the patient was admitted to pediatric clinic with a complaint of intermittent fever for 3 days. On April 19, 2006, 7 days after the admission, the patient developed a gait disturbance. Neurological examination revealed paraparesis of grade 3 on Medical Research Council (MRC) Muscle Strength Grading Scale1) with increased deep tendon reflex in both ankles, knee jerks, and bilateral positive babinski sign, but her senses were intact. Laboratory findings were inconclusive in blood cell counts, serum and urine. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) findings were as follows: elevation of protein (243.3mg/dL), and decrease of glucose (44mg/dL). Neither microorganisms nor malignant lymphocytes were detected in the CSF. The condition was suspected to be an acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy and was treated with intravenous immunoglobulin (400 mg/kg/day) for 5 days. However, her paraparesis was aggravated to grade 1 on MRC Muscle Strength Grading Scale from April 26, 2006, 14 days after the admission, and spinal MRI was performed. T2 weighted MRI demonstrated heterogeneous high signal intensity infiltration on T4 vertebral body and subligamental spreading soft tissue mass on T3-5 epidural space from T4 posterior vertebral body, causing spinal cord compression (Fig. 1). On April 27, 2006, laminectomy of T3, 4 with open biopsy were performed. The epidural mass was encircling the spinal cord mainly on ventral surface and was slightly grey to yellow, solid and compact nature. The mass was almost completely removed. A histopathologic examination showed an angiocentric distribution of polymorphous lymphoid infiltrate, with extensive necrosis. Immunohistoche mical staining for CD3 and CD20 showed the predominance of mature T cells and atypical B cells (Fig. 2). In situ hybridization revealed positivity for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) encoded RNA in a few lymphocytes, confirming the diagnosis of grade II LYG. One-week post-operative neurologic examination showed paraparesis grade 3 on MRC scale, and bare independent walking but as she still had gait impairment, she received rehabilitation. After four weeks of the surgery, she restored her normal state and could walk quite well. At that time, there were no pulmonary lesions, so we suspected the spinal lesion as the primary involvement site. Two weeks after, chest and abdomen CT revealed multiple low density nodular mass on the liver and the lower lobe of the left lung. Histopathologically, lesions were not blastic in appearance and in immunophenotype, and the lesions were negative for CD10, Tdt, and CD22, so we ruled out the relapse of ALL. She was treated with rituximab (275mg/m2/day, 4 times per week) for 4 weeks and intravenous high dose methylprednisolone (30mg/kg per day for 3 days, 20mg/kg per day for 2 days and 10mg/kg per day for 2 days). Chest and abdomen CT showed marked improvement of the lesions 3 months after the treatment compared with the lesions in the images obtained before the treatment. She was discharged from our hospital in July 2006. A follow-up MRI study performed 4 months after the operation documented no evidence of residual mass or recurrence (Fig. 3). Chest and abdomen CT performed 1 year after the operation showed no demonstrable focal lesion in lung field and mediastinum and unremarkable abdominal organs. Her weakness improved and she was able to walk independently and had no gait impairment. But unfortunately we failed to take additional follow-up of MRI for the patient, as she was terrified to take MRI and full sedation was not possible. Moreover the parents of the patient did not agree with the idea of taking MRI one more time because she was in good state at that time. To date, her condition remained stable without recurrence.

Fig. 1. Preoperative Sagittal and axial T1-weighted images (A, D) show a mass with iso signal intensity and T2-weighted images (B, E) show a heterogeneous signal mass relative to the spinal cord. And T1-weighted with gadolinium images (C, F) show heterogeneous high signal enhanced infiltration on T4 ver tebral body and subligamental spreaded epidural mass compressing the spinal cord at the T3-5 level.

Fig. 2. (A) Angiocentricity of atypical lymphoid cells are noted (hematoxylin and eosin stain, orignial magnification ×400). (B) Atypical large lymphoid cells show membranous CD20 immunoreactivity (Immunostain, orignial magnification ×400). (C) Atypical large lymphoid cells show positive signal for Epstein-Barr virus in situ hybridization (EBV in situ hybridization, original magnification ×400).

Fig. 3. Postoperative sagittal and axial T1-weighted (A, D), T2-weighted (B, E) and T1-weighted with gadolinium(C, F) images show no residual mass.

DISCUSSION

LYG is a rare lymphoproliferative disease characterized by angiocentric and angiodestructive EBV-positive B-cell proliferation of uncertain malignant potential, which might be associated with exuberant reactive T cell infiltration2,9). LYG affects men more than women with ratio 2 to 1 and presents mainly in adults between the fourth and sixth decades of life, although patients of all ages can be affected. Its occurrence in children is quite rare4). There were three cases of lymphomatoid granulomatosis with onset after ALL. Two of these patients died of the disease, only one obtained benefit from acyclovir therapy7).

LYG usually affects lungs primarily, and it may also present several significant extrapulmonary manifestations, affecting skin, kidney, spleen, and the central nervous system. Involvement of the spine has been rarely reported. To my best knowledge, this is the first report of thoracic spinal LYG presenting with unique progressive myelopathy. Because of its rarity, the definite diagnosis of LYG is difficult. However, numerous granulomatous lesions in the central nervous system and lungs are highly suggestive of LYG.

Median survival of patients with LYG is less than two years. LYG with central nervous system involvement, observed in approximately 30% of the affected patients, indicates poor prognosis4,9,11). There was only one case report about LYG with spinal involvement. In that case, LYG involve cervical spinal cord, and the patient submitted four cycles of adjuvant cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (CHOP). But the patient died 5 months after the treatment due to systemic progression of the disease7).

A grading system of LYG is based on the number of atypical lymphocytes, EBV-positive B-cells and amount of necrosis5). Pathophysiologically, grade I lesions consist of a polymorphous angiocentric and angiodestructive infiltrate of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histocytes, with or without eosinophils. Large lymphoid cells or immunoblasts were less than five in high power field (×400) or absent. If large lymphoid cells or immunoblasts were present, there would be no cellular atypia and minimal-to-absent necrosis. Grade II lesions consisted of large lymphoid cells with less than twenty EBV-positive cells in high power field with some cellular atypia in small lymphoid cells, and necrosis was more common. Grade III lesions, angiocentric lymphomas, consisted of large atypical cells with more than twenty EBV positive cells in high power field with the marked cytologic atypia in both small and large lymphoid cells4,13).

To date, no standard treatment has been established for LYG and treatments approach to systemic LYG include drugs acting on the immune system(corticosteroids, interferon alfa-2b, cyclosporine A, anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody-rituximab), mono- or combined chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and autologous stem cell transplantation. Several treatments with rituximab have been reported, with or without chemotherapy or radiotherapy3,9,10,15). Rituximab was approved for the treatment of recurrent, poorly differentiated refractory or follicular CD20 positive B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma14). In this case, immunohistochemical staining for CD3 and CD20 showed the predominance of mature T cells and atypical B cells. In situ hybridization revealed positive EBV encoded RNA in a few lymphocytes, confirming the diagnosis of grade II LYG.

The patient experienced rapid worsening of neurological symptoms and absence of systemic involvement on pre-operative laboratory findings and radiological imaging, and she therefore was treated with surgical decompression and biopsy on the T3-5 epidural lesion and improved neurologic symptoms. Surgical decompression can improve neurological morbidity of the patient. However, appropriate chemotherapy is highly needed as systemic progression of LYG make poor prognosis. The patient responded to rituximab therapy well without adverse effects, and her condition remained stable for 6 years. Therefore it was suggestive that decompression and rituximab is suitable as the initial therapy for symptomatic spinal LYG.

CONCLUSION

This case described an unusual occurrence of thoracic spinal LYG in a 4-year-old girl. Childhood LYG is a rare disease but should be considered in the nodular pulmonary infiltrates and central nervous system manifestations, especially in the past diagnosis of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Awareness of the features of LYG can lead to earlier diagnosis and prompt appropriate therapy.

References

- 1.Amidei C. Measurement of physiologic responses to mobilisation in critically ill adults. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2012;28:58–72. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heslop HE. Biology and treatment of Ebstein-Barr virus-associated non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2005;1:260–266. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2005.1.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jordan K, Grothey A, Grothe W, Kegel T, Wolf HH, Schmoll HG. Successful treatment of mediastinal lymphomatoid granulomatosis with rituximab monotherapy. Eur J Haematol. 2005;74(3):263–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2004.00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kendi AT, McKinney AM, Clark HB, Kieffer SA. A Pediatric Case of Low-Grade Lymphomatoid granulomatosis Presenting with a Cerebellar Mass. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:1803–1805. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipford EH, Jr, Margolick JB, Longo DL, Fauci AS, Jaffe ES. Angiocentric immumoproliferative lesions: a clinicopathological spectrum of post-thymic T-cell proliferations. Blood. 1998;72:1674–1681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lucantoni C, De Bonis P, Doglietto F, Esposito G, Larocca LM, Mangilola A, et al. Primary cerebral lymphomatoid granulomatosis : report of four cases and literature review. J Neurooncol. 2009;94(2):235–242. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-9834-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moertel CL, Carlson-Greeb B, Watterson J, Simonton SC. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis after childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: report of effective therapy. Pediatrics. 2001;107(5):E82. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.5.e82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montano N, Lucantoni C, Larocca LM, Papacci F, Meglio M. Cervical extramedullary lymphomatoid granulomatosis. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18(6):851–853. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2010.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao R, Vugman G, Leslie WT, Loew J, Venugopal P. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis treated with rituximab and chemotherapy. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2003;1(11):658–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sebire NJ, Haselden S, Malone M, Davies EG, Ramsay AD. Isolated EBV lymphoproliferative disease in a child with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome manisfesting as cutaneous lymphomatoid granulomatosis and responsive to anti-CD20 immunotherapy. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56(7):555–557. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.7.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tateishi U, Terae S, Ogata A, Sawamura Y, Suzuki Y, Abe S, et al. MR imaging of the brain in Lymphomatoid granulomatosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:1283–1290. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitehead VM, Shuster JJ, Vuchich MJ, Mahoney DH, Jr, Lauer SJ, Payment C, et al. Accumulation of methotrexate and methotrexate polyglutamates in lymphoblasts and treatment outcome in children with B-progenitor-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Pediatric Oncology Group study. Leukemia. 2005;19(4):533–536. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yen HL, Tsai SC, Liu SM. Infiltrating spinal angiolipoma. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15:1170–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2007.07.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yin H, Wan H, Hu XP, Li XB, Wang W, Liu H, et al. Rituximab induction therapy in highly sensitized kidney transplant recipients. Chin Med J. 2011;124(13):1928–1932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaidi A, Kampalath B, Peltier WL, Vesole DH. Successful treatment of systemic and central nervous system lymphomatoid granulomatosis with rituximab. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45(4):777–780. doi: 10.1080/10428190310001625854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]