Abstract

Background. There are few estimates of effectiveness influenza vaccine in preventing serious outcomes due to influenza in older adults.

Methods. Adults aged ≥50 years who sought medical care for acute respiratory illness were enrolled. A nose/throat swab was tested for influenza virus by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction. Clinical and demographic data were collected, including verification of receipt of trivalent inactivated influenza vaccination (IIV-3). Adjusted odds ratios were estimated by multivariable logistic regression models with an L1 penalty on all covariates except vaccination status.

Results. A total of 1047 subjects were enrolled from November through April during 5 influenza seasons during 2006–2012, excluding the 2009–2010 season. Of those enrolled, 927 (88%) had complete influenza virus testing, vaccination status, and demographic data obtained. Of 86 (9.3%) influenza virus–positive patients, 47 (55%) were vaccinated. Of 841 influenza virus–negative patients, 646 (76.8%) were vaccinated. Over 5 influenza seasons, IIV-3 was 58.4% effective (95% confidence interval [CI], 37.0%–75.6%) for the prevention of medically attended laboratory-confirmed influenza illness in adults aged ≥50 years and 58.4% effective (95% CI, 7.9%–81.1%) in adults aged ≥65 years.

Conclusions. Influenza vaccine was moderately effective in preventing influenza-associated medical care visits in older adults.

Keywords: influenza vaccine effectiveness, control-negative, older adults, elderly

Much remains to be learned about influenza vaccine effectiveness, especially in older adults. The case-positive, control-negative study design for vaccine effectiveness has been used extensively in both the United States [1–3] and Europe [4–7] to determine annual influenza vaccine effectiveness. Most of these studies focus on outpatient disease in younger adults. Only a few studies have evaluated whether influenza vaccine prevents influenza-associated hospitalizations in adults ≥65 years of age. These studies reported influenza vaccine effectiveness estimates of 42% (95% confidence interval [CI], 29%–58%) during the 2010–2011 season in Ontario, Canada [8]; 8% (95% CI, −78% to 5%) and 52% (95% CI, 32%–66%) in New Zealand in 2012 [9] and 2013 [10], respectively; and 23% (95% CI, −87% to 68%) during the 2013–2014 season in Navarre, Spain [11]. In this report, we expand on our earlier studies [2, 3] in older adults by combining 5 years of prospectively collected data to evaluate vaccine effectiveness for the prevention of hospitalization for influenza.

METHODS

Data Collection

The data reported in this article were previously collected in several different influenza vaccine effectiveness studies that used slightly different study designs. The 2006–2009 [2] and the 2011–2012 [11] data were used to evaluate vaccine effectiveness in adults ≥50 years of age. The 2008–2009 [1] and 2010–2011 [9] data were collected as part of a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cooperative agreement to assess vaccine effectiveness in all age groups at 4 separate study sites throughout the United States. The resultant combined data set used in this analysis included adults ≥50 years of age with acute respiratory illness or fever who sought medical care at one of 4 surveillance hospitals in Nashville, Davidson County, Tennessee, from November to April during 2006–2012, excluding the 2009–2010 influenza season. The 2009–2010 influenza season was excluded because peak pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus circulation in Davidson County occurred before vaccine was available, making determination of vaccine effectiveness problematic. Patients with ≥1 of the following admission diagnoses (and International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision codes) were eligible: pneumonia (480–486), upper respiratory tract infection (465), bronchitis (466), influenza (487), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (490 to 492; 496), asthma (493), viral illness (079.9) [12], dyspnea (786), acute respiratory failure (518.81), pneumonitis due to solids/liquids (507), or fever (780.6) without localizing symptoms or presenting symptoms of cough, nonlocalizing fever, shortness of breath, sore throat, nasal congestion, or coryza. All who qualified for the study were approached to obtain informed consent either from the patient or the patient's legally authorized representative. In rare instances, when no authorized person was available, a waiver of consent was used, since testing for influenza virus was time sensitive. Only adults incapable of self-consent without a surrogate could be enrolled via a waiver. Research personnel recorded patient-reported symptoms, smoking history, receipt of influenza vaccination, and use of certain medications (including steroids and home oxygen use), using a standard data collection form. One nasal and one throat swab were obtained from each subject and tested for influenza virus in a research laboratory, using CDC primers and probes [1, 3]. After discharge, information abstracted from medical records included demographic data, past medical history, results of microbiologic tests, hospital course (if hospitalized), outcome of illness at discharge, and verification of influenza vaccination status. Study staff verified vaccinations from both the medical record and nontraditional providers, such as retail stores, employers, military, and public health officials. If a participant denied vaccination, we confirmed this with the primary care provider or nursing facility.

Laboratory Analyses

The nasal and throat specimens were aliquoted into a commercial lysis buffer compatible for RNA extraction. All specimens were tested for either β-actin (during the 2006–2008 influenza seasons) or RNase P (during the 2008–2009 and 2010–2012 seasons) to ensure the quality of the specimens obtained. Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) primers and probes for influenza testing were designed by and kindly provided by Steve Lindstrom of the CDC [13]. Testing distinguished between influenza A and B viruses and between influenza A virus subtypes H1N1 and H3N2. If specimens were found to be positive, a confirmatory second assay was performed.

Definitions

A person was considered to be immunized if they were vaccinated at least 2 weeks before the onset of symptoms. Influenza virus–positive cases were defined as participants with positive RT-PCR results on duplicate testing. Influenza virus–negative controls were defined as participants with respiratory illness who tested negative for influenza virus by RT-PCR and had evidence of β-actin or RNase P in the sample. Patients with indeterminate laboratory results or unknown vaccination status were excluded from the analyses. Influenza seasons were defined by the total number of weeks that included all influenza virus–positive specimens obtained from enrolled participants each year.

Covariates

Covariates obtained by self-report or chart review included age in years; sex; race (black or nonblack); current smoking (in the past 6 months); home oxygen use; underlying medical conditions, including diabetes mellitus, chronic liver or kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asplenia (functional or anatomic), and immunosuppression (due to human immunodeficiency virus infection, corticosteroid use, or cancer); timing of admission relative to the onset of influenza season, which was defined as the week of each influenza season; the specific influenza season; and insurance. All covariates were considered as potential confounders.

Analysis

Characteristics of vaccinated and nonvaccinated patients and influenza virus–positive cases and influenza virus–negative controls were compared using the Pearson χ2 test for categorical covariates and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables. Vaccine effectiveness estimates were calculated using the formula [1 − adjusted OR] × 100%, where “OR” denotes the odds ratio [14]. Adjusted ORs for individual years and all years were estimated by multivariable logistic regression models with an L1 penalty on all covariates except vaccination status (LASSO). The model outcome was influenza virus–positive cases or negative controls, and the exposure of interest was vaccination status, with adjustment for the other covariates listed above. Restricted cubic spline function was applied to the variables age and week of influenza season, with 3 knots for each variable. The LASSO method was chosen because the number of parameters to be included in the model was large relative to the number of cases available. The penalty function yields 0 estimates when the parameter values are close to 0 and, thus, the LASSO method can perform the variable selection procedure [15]. To further evaluate the effect of age on vaccine effectiveness, we added the interaction between vaccination and age to the model. In addition, vaccination, age, and the interaction between vaccination and age were exempt from penalization. The 95% point-wise confidence band of age effect was constructed using the 2.5% and 97.5% quantiles of 5000 bootstrap samples. To evaluate the age effect on vaccine effectiveness, the deviance difference between this model and the model without vaccination by age interaction was calculated, and a P value was constructed by assuming that the deviance difference follows an approximately χ2 distribution with 2 degrees of freedom under the null hypothesis.

Two sensitivity analyses were performed. The first analysis collapsed all previously listed high-risk conditions into one variable termed “high risk” with the values “yes” and “no.” The second sensitivity analysis was conducted including patients with any missing covariates (except for immunization status and influenza virus testing results) after performing multiple imputations. All analyses were performed using R3.0.2 (http://www.r-project.org).

RESULTS

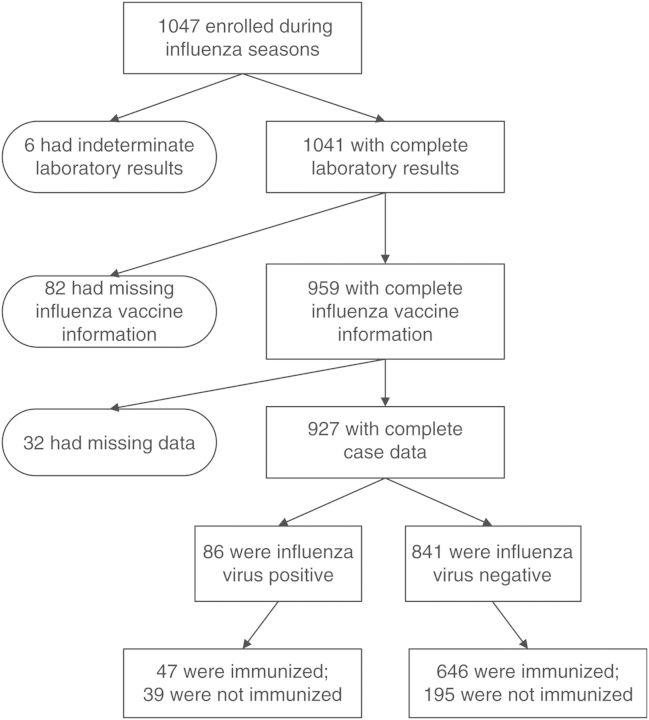

During the 5 influenza seasons, 1047 participants ≥50 years of age were enrolled (Figure 1). Of these, 1041 had complete influenza virus test results (ie, no indeterminate laboratory results), and 927 (88%) also had known vaccination status and complete demographic and clinical information (Figure 1). These 927 participants were more likely to be white (73% vs 55%; P < .001), less likely to have heart disease (48% vs 60%; P = .01), and less likely to have an intensive care unit admission (10% vs 18%; P = .01) than those with incomplete data. Otherwise, the 2 groups were similar.

Figure 1.

Selection of study participants.

A total of 10% of patients were influenza virus positive. Vaccinated subjects were similar to unvaccinated subjects (Table 1), except vaccinated subjects were older (P < .001), less likely to be current smokers (P = .003), less likely to have influenza (P < .001), more likely to be white (P < .001), and more likely to have cardiac disease (P = .01). Influenza virus–positive patients were similar to influenza virus–negative patients, except influenza virus–positive patients were less likely to be vaccinated (P < .001).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Patients, by Influenza Vaccination Status and Influenza Virus Status

| Characteristic | Vaccination Status |

Influenza Virus Status |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Vaccinated (n = 234) | Vaccinated (n = 693) | P values | Negative (N = 841) | Positive (N = 86) | P values | |

| Race | <.001 | .5 | ||||

| White | 62 (144) | 77 (532) | 73 (617) | 69 (59) | ||

| Black | 37 (87) | 22 (149) | 25 (210) | 30 (26) | ||

| Other | 1 (3) | 2 (12) | 2 (14) | 1 (1) | ||

| Age, y | 62.1 (55.7–71.6) | 69.4 (60.8–79.1) | <.001 | 67.8 (59.3–77.6) | 63.9 (56.3–73.6) | .06 |

| Female sex | 62 (146) | 59 (408) | .3 | 59 (499) | 64 (55) | .4 |

| High-risk medical condition | ||||||

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 50 (117) | 55 (383) | .2 | 54 (452) | 56 (48) | .7 |

| Chronic cardiovascular disease | 41 (96) | 51 (351) | .01 | 48 (407) | 46 (40) | .7 |

| Immunosuppressiona | 30 (70) | 33 (231) | .3 | 33 (274) | 31 (27) | .8 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 30 (71) | 37 (257) | .06 | 35 (298) | 35 (30) | .9 |

| Kidney or liver disease | 14 (32) | 18 (126) | .1 | 18 (148) | 12 (10) | .2 |

| Asplenia | 1 (2) | 1 (5) | .8 | 1 (6) | 1 (1) | .6 |

| Current smoking | 31 (72) | 21 (148) | .003 | 23 (193) | 31 (27) | .08 |

| Influenza virus positive | 17 (39) | 7 (47) | <.001 | … | … | |

| Vaccinated | … | … | 77 (646) | 55 (47) | <.001 | |

| ICU admission | 11 (25) | 10 (72) | .9 | 11 (91) | 7 (6) | .3 |

| Death | 1 (2) | 3 (16) | .1 | 3 (17) | 1 (1) | .5 |

| Length of stay, d | 3.0 (2.0–6.0) | 3.0 (2.0–6.0) | .2 | 3.0 (2.0–6.0) | 3.0 (2.0–5.0) | .3 |

| Discharge diagnosisb | .8 | .6 | ||||

| Pneumonia and influenza | 41 (96) | 41 (285) | 41 (345) | 42 (36) | ||

| Other acute respiratory illness | 9 (21) | 8 (57) | 8 (71) | 8 (7) | ||

| Asthma or COPD exacerbation | 26 (61) | 29 (203) | 28 (235) | 34 (29) | ||

| Cardiac disease | 11 (25) | 10 (68) | 10 (88) | 6 (5) | ||

Data are no. (%) of patients or median (interquartile range).

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

a Defined as the presence of one of the following: history of transplantation, human immunodeficiency virus infection, and recent or chronic use of steroids, chemotherapy, or use of other immunosuppressive medications.

b Discharge diagnoses were grouped into 5 categories: pneumonia and influenza (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes: 480–482, 485–488), other acute respiratory illness (033, 034, 077, 372, 381, 382, 384, 385, 388, 460–466, and 473), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma (490–494 and 496), cardiac disease (410, 411, 413, 428, and 785), and other (any remaining codes).

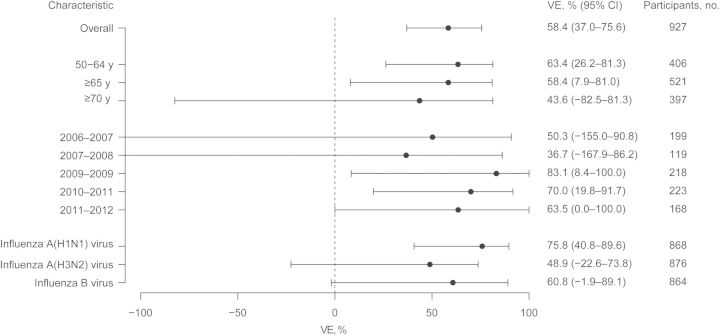

Vaccine effectiveness in adults ≥50 years of age for the prevention of a medically attended, laboratory-confirmed acute respiratory illness due to influenza was 58.4% (95% CI, 37.0%–75.6%). Vaccine effectiveness estimates for those ≥65 years of age were 58.4% (95% CI, 7.9%–81.0%). Over the 5 influenza seasons, vaccine effectiveness ranged from 36.7% to 83.1%, with varying widths of CIs related to seasonal sample sizes (Figure 2). The estimated vaccine effectiveness was graphed as a function of age, with increasing age associated with lower vaccine effectiveness and wider CIs (Figure 3). Despite the visual appearance of a decrease of vaccine effectiveness with age, the trend was not statistically significant (P = .19).

Figure 2.

Vaccine effectiveness (VE), overall, by age, by influenza season, and by influenza virus type or subtype. For confidence intervals (CIs), lower limits less than −100% are truncated at −100% in the graph. Beside each value of VE is the number of participants in each group.

Figure 3.

Vaccine effectiveness as a function of patient age. A LASSO logistic regression model was fitted for influenza regressed on vaccination, with adjustment for age at enrollment, sex, race, current smoking, home oxygen use, underlying medical condition, timing of admission relative to influenza season, specific influenza season, insurance, and site of enrollment. Restricted cubic spline was applied to age and week of influenza season variables, with 3 knots for each variable. The interaction between vaccination and age was also included in the model. Vaccination, age (linear and nonlinear), and interactions between vaccination and age were not penalized. The gray zone is a 95% point-wise confidence band.

Vaccine effectiveness was determined individually for influenza A(H1N1), A(H3N2), and B viruses. Vaccine effectiveness was highest for influenza A(H1N1) virus, with an estimated effectiveness of 75.8% (95% CI, 40.8%–89.6%), followed by 60.8% (95% CI, −1.9% to 89.1%) for influenza B virus. Effectiveness for influenza A(H3N2( virus was 48.9% (95% CI, −22.6% to 73.8%).

The sensitivity analysis collapsing high-risk variables into a single variable gave an overall vaccine effectiveness of 63.6% (95% CI, 37.7%–76.3%), higher than the estimate of 58.4% (95% CI, 37.0%–75.6%) when the high-risk variables were individually included. The second sensitivity analyses, which used imputed data, produced results similar to that for the complete data set (vaccine effectiveness, 59.7%; 95% CI, 39.1%–76.3%).

DISCUSSION

Influenza vaccine effectiveness appeared to vary yearly, likely in part because of differences in circulating influenza viruses, changes in vaccine composition, and matches between the circulating strains and vaccine strains. However, annual estimates were imprecise, and over the 5 years, the influenza vaccine was moderately effective for the prevention of healthcare visits. Using 5 years of prospectively collected data, we found vaccine effectiveness for the prevention of medically attended visits to be 58.4% (95% CI, 37.0%–75.6%) for adults ≥50 years of age and 58.4% (95% CI, 7.9%–81.0%) for adults ≥65 years of age.

Yearly influenza vaccine effectiveness estimates are calculated in the United States and Europe [7, 16, 18–20]. This study combines data from multiple years and shows that the overall impact of the immunization of older adults over several seasons is moderately effective for the prevention of hospitalizations.

Vaccine effectiveness appeared to decline with age, but we had an insufficient sample size to determine modest declines due to age. Because of small numbers of influenza cases in adults ≥70 years of age, our estimates of vaccine effectiveness in that age group are imprecise. It is unclear whether the low number of cases is due to the very high vaccination rates in this population, delay in presentation with lower concentrations of virus, or atypical presentations that may not be captured by our enrollment criteria. This older population, which is at the greatest risk for influenza-associated morbidity and mortality, has been the most difficult group in which to establish vaccine effectiveness estimates. A randomized controlled trial in 1991 [17] showed vaccine effectiveness in adults ≥60 years of age but was not powered to determine the vaccine effectiveness in adults aged ≥70 years, for which the total sample size was 544 (vaccine effectiveness, 57% (95% CI, −36% to 87%) [16]. Our vaccine effectiveness estimate in adults ≥70 years of age was 43.6% (95% CI, −82.5% to 81.3%). Studies of this high-risk group in the United States are challenging, in part because of high vaccination rates.

In our sensitivity analysis, the collapsed high-risk indicator model yielded a lower vaccine effectiveness estimate than the model controlling for individual disease risk factors (51.6% vs 61.9%), implying that the collapsed high-risk indicator model might not be able to control all of the confounding effects from disease risk factors. Thus, the use of state-of-the-art shrinkage methods like LASSO may enhance our ability to include a large number of covariates when performing vaccine effectiveness studies using the case-positive, control-negative study design, when the number of study subjects is small.

Influenza vaccine effectiveness also relies on the similarity between circulating and vaccine strains. We found that this was true in our results. The 2006–2007 influenza season [2] had poor matching of circulating and vaccine strains, and the 2007–2008 [2] had a fair match of strains. These 2 seasons had the lowest vaccine effectiveness estimates. The 3 remaining seasons had better matching between vaccine and circulating strains and higher vaccine effectiveness estimates. Vaccines for the 2008–2009 [2] and the 2011–2012 [23] influenza seasons were good matches for both influenza A virus strains but poor matching for the influenza B virus strain alone. The 2010–2011 [24] had good matching for all three strains.

This study has several limitations. First, the study was conducted at a single study site, and it is unclear whether these results can be generalizable to other locations. Second, there were small numbers of influenza virus detections in each study year, making it difficult to determine vaccine effectiveness for individual study years. Thus, the results of this study are a composite of vaccine effectiveness over 5 years, representing several different vaccine strains. Data on the duration of symptoms were not reliably collected in the first year of the study and were not included in the analyses. Some controls could truly be cases; this would result in a bias toward the null hypothesis and yield conservative estimates of vaccine effectiveness. Last, high-dose influenza vaccine was licensed for 2 years of the study, but uptake was very low. Therefore, no estimates of the effectiveness of high-dose vaccine could be determined.

This study highlights the need for more-effective vaccines in older adults. Until newer vaccines are available, the current inactivated influenza vaccine is moderately effective and should be used in older adults to prevent medically attended acute respiratory infections due to influenza virus.

Notes

Disclaimer. The funders did not participate in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Vaccine Treatment and Evaluation Units (grant N01 AI25462; K. M. E., site principal investigator [PI]), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (grant 1U181P000184-01; M. G., site PI), RTI/CDC (contract 200-2008-24624 to RTI International; M. G., site PI); the National Institute on Aging (grant 1R01AG043419; H. K. T., PI); and the Vanderbilt Clinical and Translational Science Award Program (award 1 UL1 RR024975, from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health).

Potential conflicts of interest. H. K. B. T. has received funding from Sanofi-Pasteur and MedImmune. M. R. G. has received funding from MedImmune. J. V. W. has served as a consultant for Quidel. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Griffin MR, Monto AS, Belongia EA, et al. Effectiveness of non-adjuvanted pandemic influenza A vaccines for preventing pandemic influenza acute respiratory illness visits in 4 U.S. communities. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Talbot HK, Griffin MR, Chen Q, Zhu Y, Williams JV, Edwards KM. Effectiveness of seasonal vaccine in preventing confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations in community dwelling older adults. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:500–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talbot HK, Zhu Y, Chen Q, Williams JV, Thompson MG, Griffin MR. Effectiveness of influenza vaccine for preventing laboratory-confirmed influenza hospitalizations in adults, 2011–2012 influenza season. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:1774–7. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amour S, Voirin N, Regis C, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness among adult patients in a University of Lyon hospital (2004–2009) Vaccine. 2011;30:821–4. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castilla J, Godoy P, Dominguez A, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in preventing outpatient, inpatient, and severe cases of laboratory-confirmed influenza. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:167–75. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castilla J, Martinez-Artola V, Salcedo E, et al. Vaccine effectiveness in preventing influenza hospitalizations in Navarre, Spain, 2010–2011: Cohort and case-control study. Vaccine. 2011;30:195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kissling E, Valenciano M. Early estimates of seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness in Europe, 2010/11: I-MOVE, a multicentre case-control study. Euro Surveill. 2011;16 doi: 10.2807/ese.16.11.19818-en. pii:19818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwong JC, Campitelli MA, Gubbay JB, et al. Vaccine effectiveness against laboratory-confirmed influenza hospitalizations among elderly adults during the 2010–2011 season. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:820–7. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turner N, Pierse N, Bissielo A, et al. Effectiveness of seasonal trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine in preventing influenza hospitalisations and primary care visits in Auckland, New Zealand, in 2013. Euro Surveill. 2014;19 pii:20884. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turner N, Pierse N, Bissielo A, et al. The effectiveness of seasonal trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine in preventing laboratory confirmed influenza hospitalisations in Auckland, New Zealand in 2012. Vaccine. 2014;32:3687–93. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castilla J, Martinez-Baz I, Navascues A, et al. Vaccine effectiveness in preventing laboratory-confirmed influenza in Navarre, Spain: 2013/14 mid-season analysis. Euro Surveill. 2014;19 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2014.19.6.20700. pii:20700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Treanor JJ, Talbot HK, Ohmit SE, et al. Effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccines in the United States during a season with circulation of all three vaccine strains. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:951–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falsey AR, Hennessey PA, Formica MA, Cox C, Walsh EE. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in elderly and high-risk adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1749–59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kandun IN, Wibisono H, Sedyaningsih ER, et al. Three Indonesian clusters of H5N1 virus infection in 2005. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2186–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orenstein WA, Bernier RH, Dondero TJ, et al. Field evaluation of vaccine efficacy. Bull World Health Organ. 1985;63:1055–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J Stat Softw. 2010;33:1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flannery B, Thaker SN, Clippard J, et al. Interim estimates of 2013–14 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness—United States, February 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:137–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Interim adjusted estimates of seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness—United States, February 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:119–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Early estimates of seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness—United States, January 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:32–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valenciano M, Kissling E, Cohen JM, et al. Estimates of pandemic influenza vaccine effectiveness in Europe, 2009–2010: results of Influenza Monitoring Vaccine Effectiveness in Europe (I-MOVE) multicentre case-control study. PLoS Med. 2011;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000388. e1000388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Govaert TM, Thijs CT, Masurel N, Sprenger MJ, Dinant GJ, Knottnerus JA. The efficacy of influenza vaccination in elderly individuals. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. JAMA. 1994;272:1661–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thijs C, Beyer WE, Govaert PM, Sprenger MJ, Dinant GJ, Knottnerus A. Mortality benefits of influenza vaccination in elderly people. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:460–1. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70161-0. author reply 463–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Update: influenza activity—United States, September 30 November 24, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:990–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2010–2011 Influenza (Flu) Season. http://www.cdc.gov/flu/pastseasons/1011season.htm . Accessed September 24, 2014.