Abstract

Background. Human papillomavirus (HPV) causes external genital lesions (EGLs) in men, including condyloma and penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PeIN). We sought to determine the incidence of pathologically confirmed EGLs, by lesion type, among men in different age groups and to evaluate the HPV types that were associated with EGL development.

Methods. HPV Infection in Men (HIM) study participants who contributed ≥2 visits from 2009–2013 were included in the biopsy cohort. Genotyping by an HPV line-probe assay was performed on all pathologically confirmed EGLs. Age-specific analyses were conducted for incident EGLs, with Kaplan–Meier estimation of cumulative incidence.

Results. This biopsy cohort included 2754 men (median follow-up duration, 12.4 months [interquartile range, 6.9–19.2 months]). EGLs (n = 377) were pathologically confirmed in 228 men, 198 of whom had incident EGLs. The cumulative incidence of any EGL was highest among men <45 years old and, for condyloma, decreased significantly over time with age. The genotype-specific incidence of EGL varied by pathological diagnoses, with high- and low-risk genotypes found in 15.6% and 73.2% of EGLs, respectively. Condyloma primarily contained HPV 6 or 11. While PeIN lesions primarily contained HPV 16, 1 PeIN III lesion was positive for HPV 6 only.

Conclusion. Low- and high-risk HPV genotypes contribute to the EGL burden. Men remain susceptible to HPV-related EGLs throughout the life span, making it necessary to ensure the longevity of immune protection against the most common causative HPV genotypes.

Keywords: human papillomavirus (HPV), genotype, age, external genital lesions, penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PeIN), condyloma, HIM Study

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is known to cause external genital lesions (EGLs) in men, including condylomata acuminata, commonly referred to as condyloma or genital warts, as well as penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PeIN), which is believed to be a precursor to penile cancer [1]. While HPV-related condyloma is considered a benign lesion, the substantial economic and psychosocial burden of this clinical manifestation of infection cannot be overlooked. The incidence of penile cancer is increasing globally, with incidence rates in Brazil among the highest worldwide [2] and no routine screening tests available for penile cancer or the precursor PeIN lesions.

Studies of HPV-related EGLs have primarily been limited to condyloma and low-risk HPV genotypes 6 and 11, owing to the rarity of PeIN and the lack of long-term, prospective cohorts of men. Studies to determine the role of other high- or low-risk types in the etiology of these EGLs are similarly limited. A quadrivalent vaccine, offering protection against HPV genotypes 6 and 11 and high-risk HPV genotypes 16 and 18, has been demonstrated as efficacious in men [3] but has not yet been approved for the prevention of penile cancer. This vaccine is also approved only for use in young men (ages 9–26 years); it is recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for males ages 11–22 years and for high-risk males aged up to 26 years, but no HPV vaccine prevention options are currently available for men at older ages.

Further studies of the causative HPV genotypes of benign and precancerous lesions and the ages at which these lesions occur are necessary to inform development of prevention and screening strategies. Using the established HPV Infection in Men (HIM) study cohort, a multinational study of men across the life span from the United States, Brazil, and Mexico, we sought to determine the incidence of pathologically confirmed EGLs, by lesion type, among men in different age groups and to evaluate the HPV types that were associated with EGL development.

METHODS

The biopsy cohort was nested within the HIM study, a prospective, multinational study of HPV in >4000 men from Tampa, Florida, Cuernavaca, Mexico, and Sao Paulo, Brazil. Details of HIM study participants and procedures are published elsewhere [4]. Men in the HIM study biopsy cohort were required to have ≥2 study visits, approximately 6 months apart, following implementation of the HIM study pathology protocol in February 2009 and prior to May 2013.

At each clinic visit, men were examined under 3× light magnification by a trained clinician for the presence of EGLs. An exfoliated cell specimen was collected from the surface of each lesion, using a prewetted polyethylene terephthalate–tipped swab, which was stored in specimen transport medium (STM, Qiagen) at −80°C prior to DNA extraction and HPV genotyping. A tissue sample was also obtained from each lesion by shave excision. Excised tissue was placed in 10% buffered formalin and processed by the Dermatopathology Laboratory at the University of South Florida for histologic diagnosis by 2 independent pathologists. EGLs were categorized as condyloma, suggestive of condyloma, PeIN, or not HPV related, based on previously reported criteria [5]. PeIN lesions were further categorized as PeIN I (low-grade squamous dysplasia), PeIN II (moderate squamous dysplasia), PeIN II/III (moderate squamous dysplasia with focal high-grade dysplasia), and PeIN III (high-grade squamous dysplasia/carcinoma in situ).

A panel of 3 independent pathologists was convened to adjudicate discrepant diagnoses and to perform quality control of diagnoses for 10% of all biopsy specimens. All EGLs that appeared to be HPV related (ie, condyloma and PeIN) or had an unknown etiology on the basis of visual inspection were sent for HPV testing. Only lesions that were clearly not HPV related and had distinct features of other types of lesions, such as herpes simplex virus, pearly penile papules, and Molluscum contagiosum, were not sampled.

Shave excision specimens were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin. DNA was extracted from these formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens by using the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and genotyping was performed to detect HPV DNA, using an AutoBlot 3000H processor (MedTec Biolab) and the INNO-LiPA Genotyping Extra assay (Fujirebio), which detects 28 HPV genotypes classified as high- or low-risk, depending on their association with development of carcinoma (high-risk types: 16, 18, 26, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68, 73, and 82; low-risk types: 6, 11, 40, 43, 44, 54, 69, 70, 71, and 74).

Statistical Methods

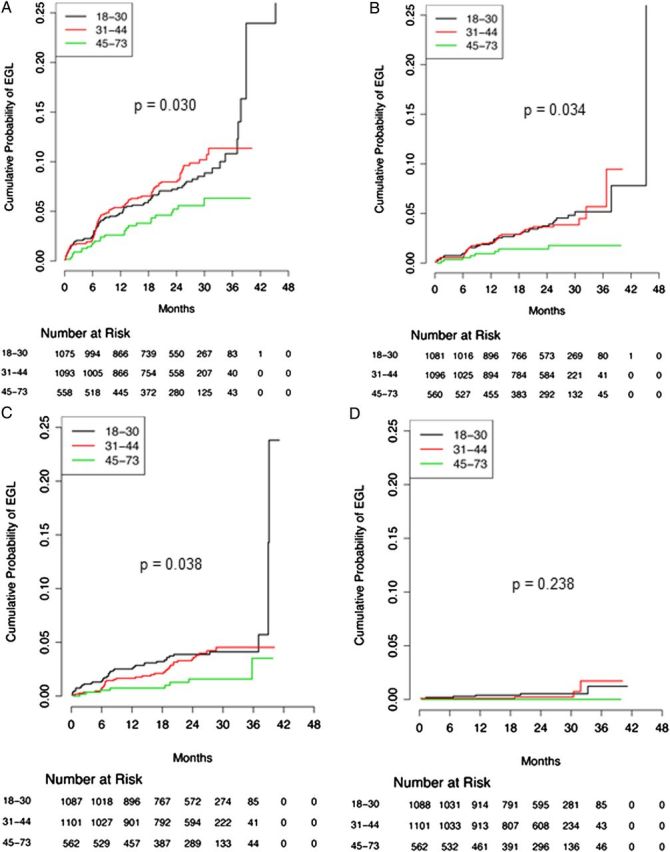

Demographic and sexual behavior characteristics were described for the men included in the HIM study biopsy cohort and those in the HIM study who were not included in the biopsy cohort (Table 1). Age-specific analyses were conducted among men who developed an incident EGL within this cohort, stratified by age group, as follows: 18–30, 31–44, and 45–73 years. An additional EGL category, “condyloma combined,” was also created, which included all results for lesions diagnosed as either condyloma or suggestive of condyloma. For EGL incidence analyses, only the first acquired EGL was considered, and only men who tested negative for any EGL or a type-specific EGL at the biopsy cohort baseline were included. Time to a newly acquired EGL was calculated from baseline to the date of first EGL detection. Person-time incidence was calculated, and the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were based on the number of events modeled as a Poisson variable for the total number of person-months. Kaplan–Meier curves for EGL incidence were generated (Figure 1), and the incidence of EGL over time across the 3 age groups was compared using the log-rank test. The cumulative incidence of developing an EGL within the first 12 months of follow-up was also estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method (Table 2).

Table 1.

Differences in Sociodemographic and Sexual Behavior Characteristics Between Men Included and Men Not Included in the Biopsy Cohort of the Human Papillomavirus Infection in Men Study

| Characteristic | Included (n = 2754) | Not Included (n = 1329) | Overall (n = 4083) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country of residence | |||

| United States | 934 (33.9) | 392 (29.5) | 1326 (32.5) |

| Brazil | 1025 (37.2) | 385 (29.0) | 1410 (34.5) |

| Mexico | 795 (28.9) | 552 (41.5) | 1347 (33.0) |

| Age, y | |||

| Median (IQR) | 34 (25–43) | 29 (23–38) | 32 (24–41) |

| 18–30 | 1090 (39.6) | 708 (53.3) | 1798 (44.0) |

| 31–44 | 1102 (40.0) | 486 (36.6) | 1588 (38.9) |

| 45–73 | 562 (20.4) | 135 (10.2) | 697 (17.1) |

| Race | |||

| White | 1292 (46.9) | 516 (38.8) | 1808 (44.3) |

| Black | 458 (16.6) | 171 (12.9) | 629 (15.4) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 79 (2.9) | 32 (2.4) | 111 (2.7) |

| Mixed race/other | 860 (31.2) | 572 (43.0) | 1432 (35.1) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 1159 (42.1) | 668 (50.3) | 1827 (44.7) |

| Non-Hispanic | 1551 (56.3) | 628 (47.3) | 2179 (53.4) |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 1089 (39.5) | 318 (23.9) | 1707 (41.8) |

| Married/cohabitating | 1349 (49.0) | 592 (44.5) | 1941 (47.5) |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 270 (9.8) | 110 (8.3) | 380 (9.3) |

| Education, y | |||

| ≤12 | 1153 (41.9) | 704 (53.0) | 1857 (45.5) |

| 13–15 | 729 (26.5) | 328 (24.7) | 1057 (25.9) |

| ≥16 | 822 (29.8) | 287 (21.6) | 1109 (27.2) |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never | 1723 (62.6) | 693 (52.1) | 2416 (59.2) |

| Former | 383 (13.9) | 252 (19.0) | 635 (15.6) |

| Current | 602 (21.9) | 375 (28.2) | 977 (23.9) |

| Alcohol intake, drinks/month | |||

| 0 | 641 (23.3) | 299 (22.5) | 940 (23.0) |

| 1–30 | 1174 (42.6) | 597 (44.9) | 1771 (43.4) |

| 31–60 | 316 (11.5) | 143 (10.8) | 459 (11.2) |

| >60 | 506 (18.4) | 245 (18.4) | 751 (18.4) |

| Circumcision | |||

| No | 1706 (61.9) | 863 (64.9) | 2569 (62.9) |

| Yes | 1029 (37.4) | 442 (33.3) | 1471 (36.0) |

| Condom use during vaginal sex | |||

| No recent vaginal sex | 479 (17.4) | 235 (17.7) | 714 (17.5) |

| Always | 402 (14.6) | 255 (19.2) | 657 (16.1) |

| Sometimes | 845 (30.7) | 380 (28.6) | 1225 (30.0) |

| Never | 912 (33.1) | 431 (32.4) | 1343 (32.9) |

| Condom use during anal sex | |||

| No recent anal sex | 1952 (70.9) | 883 (66.4) | 2835 (69.4) |

| Always | 212 (7.7) | 120 (9.0) | 332 (8.1) |

| Sometimes | 188 (6.8) | 94 (7.1) | 282 (6.9) |

| Never | 325 (11.8) | 161 (12.1) | 486 (11.9) |

| Sexual orientation | |||

| MSW | 2270 (82.4) | 1105 (83.1) | 3375 (82.7) |

| MSM | 110 (4.0) | 50 (3.8) | 160 (3.9) |

| MSMW | 209 (7.6) | 62 (4.7) | 271 (6.6) |

| Female sex partners, lifetime no. | |||

| 0–1 | 369 (13.4) | 231 (17.4) | 600 (14.7) |

| 2–9 | 1019 (37.0) | 572 (43.0) | 1591 (39.0) |

| 10–49 | 1046 (38.0) | 383 (28.8) | 1429 (35.0) |

| ≥50 | 245 (8.9) | 66 (5.0) | 311 (7.6) |

| Male anal sex partners, lifetime no. | |||

| 0 | 2260 (82.1) | 1155 (86.9) | 3415 (83.6) |

| 1–9 | 320 (11.6) | 102 (7.7) | 422 (10.3) |

| ≥10 | 136 (4.9) | 48 (3.6) | 184 (4.5) |

| Prior history of HSV2 | |||

| No | 1752 (63.6) | 1117 (84.0) | 2869 (70.3) |

| Yes | 996 (36.2) | 210 (15.8) | 1206 (29.5) |

| Current diagnosis of chlamydial infection | |||

| No | 2712 (98.5) | 1305 (98.2) | 4017 (98.4) |

| Yes | 39 (1.4) | 23 (1.7) | 62 (1.5) |

Data are no. (%) of men, unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviation: HSV2, herpes simplex virus 2; IQR, interquartile range; MSM, men who have sex with men; MSW, men who have sex with women; MSWM, men who have sex with women and men.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves showing differences in cumulative incidence of external genital lesions (EGLs) over time, by age group. A, Any EGL. B, Condyloma. C, Suggestive of condyloma. D, Penile intraepithelial neoplasia. P values were determined using the log-rank test and denote differences across the entire follow-up period, by age group. Values < .05 are considered statistically significant.

Table 2.

Age-Specific Incidence of Incident, Pathologically Confirmed External Genital Lesions (EGLs) Among Men in the Human Papillomavirus Infection Study

| Variable | Pathological Diagnosis |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any EGLa | Condyloma | Suggestive of Condylomab | Condyloma Combinedc | PeIN | Otherd | |

| All ages (n = 2726)e | ||||||

| Men with incident EGLs, no. | 198 | 88 | 85 | 143 | 11 | 68 |

| Person-months | 59 582 | 61 321 | 61 620 | 60 490 | 62 687 | 61 830 |

| Incidence ratef (95% CI) | 4.0 (3.5–4.6) | 1.7 (1.4–2.1) | 1.7 (1.3–2.1) | 2.8 (2.4–3.3) | 0.2 (.1–.4) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) |

| 12-month incidence, % (95% CI) | 4.6 (3.8–5.4) | 1.8 (1.3–2.3) | 1.8 (1.3–2.3) | 3.2 (2.5–3.9) | 0.2 (.0–.4) | 1.4 (.9–1.8) |

| 18–30 y | ||||||

| Men with incident EGLs, no. | 83 | 42 | 41 | 68 | 6 | 21 |

| Person-months | 23 836 | 24 491 | 24 539 | 24 098 | 25 087 | 24 935 |

| Incidence ratef (95% CI) | 4.2 (3.3–5.2) | 2.1 (1.5–2.8) | 2.0 (1.4–2.7) | 3.4 (2.6–4.3) | 0.3 (.1–.6) | 1.0 (.7–1.5) |

| 12-month incidence, % (95% CI) | 4.8 (3.5–6.1) | 2.0 (1.1–2.8) | 2.5 (1.6–3.5) | 3.8 (2.6–5.0) | 0.4 (.0–.8) | 0.8 (.2–1.3) |

| 31–44 y | ||||||

| Men with incident EGLs, no. | 89 | 38 | 36 | 59 | 4 | 34 |

| Person-months | 23 499 | 24 264 | 24 474 | 23 963 | 24 855 | 24 413 |

| Incidence ratef (95% CI) | 4.5 (3.7–5.6) | 1.9 (1.3–2.6) | 1.8 (1.2–2.4) | 3.1 (2.3–3.8) | 0.2 (.1–.5) | 1.7 (1.2–2.3) |

| 12-month incidence, % (95% CI) | 5.4 (4.0–6.8) | 2.1 (1.2–3.0) | 1.6 (.9–2.4) | 3.4 (2.3–4.5) | 0.1 (.0–.3) | 2.1 (1.2–2.9) |

| 45–73 y | ||||||

| Men with incident EGLs, no. | 26 | 8 | 8 | 16 | 0 | 13 |

| Person-months | 12 248 | 12 566 | 12 607 | 12 428 | 12 745 | 12 482 |

| Incidence ratef (95% CI) | 2.6 (1.7–3.7) | 0.8 (.3–1.5) | 0.8 (.3–1.5) | 1.5 (.9–2.5) | 0 (.0–.4) | 1.3 (.7–2.1) |

| 12-month incidence, % (95% CI) | 2.6 (1.2–4.0) | 0.9 (.1–1.8) | 0.7 (.0–1.5) | 1.7 (.6–2.8) | 0.0 (.0–.0) | 1.3 (.3–2.2) |

| Pg | .030 | .034 | .038 | .021 | .238 | .294 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; PeIN, penile intraepithelial neoplasia (I–III).

a Men with ≥1 incident, pathologically confirmed EGL throughout the study period. For men with >1 EGL, incidence rates for the Any EGL category are determined for the first detected lesion; thus, men may contribute fewer person-months in this category than for specific pathological diagnoses.

b Includes lesions suggestive but not diagnostic of HPV infection or condyloma.

c Includes both Condyloma and Suggestive of Condyloma categories.

d Includes various HPV-unrelated skin conditions, such as seborrheic keratosis and skin tags.

e Although the initial cohort included 2754 men, 28 men with prevalent EGLs were excluded in this analysis.

f Specified as the number of cases per 100 person-years.

g Determined using the log-rank test and correspond to overall differences in EGL incidence across the entire follow-up period, by age group. Values < .05 are considered statistically significant.

For genotype-specific analyses, all prevalent and incident lesions were included. In addition to specific HPV types, infections positive for ≥1 type were included in the any HPV group, those positive for ≥1 high-risk HPV type were included in the high-risk HPV group, and those positive for ≥1 low-risk types were included in the low-risk HPV group. Independent analyses were conducted for high-risk and low-risk infections. Additionally, EGLs that were positive for ≥1 high-risk type and ≥1 low-risk type were included in the HR/LR HPV group.

In light of the recent evidence highlighting the efficacy and safety of an investigational nonavalent HPV vaccine that offers protection against HPV types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58 [6, 7], we also explored the relative contribution of these 9 types and the 4 types of the currently licensed vaccine to EGL development in men. EGLs for which DNA from the tissue biopsy specimen contained ≥1 of the quadrivalent vaccine types (HPV 6, 11, 16, or 18) were included in the quadrivalent vaccine group. Specimens that were positive for ≥1 of the nonavalent HPV vaccine types (6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, or 58) were included in the nonavalent vaccine group.

All participants provided written informed consent. Study protocols were approved by the institutional review boards at the University of South Florida (Tampa), the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research and the Centro de Referencia e Treinamento em Doencas Sexualmente Transmissveis e AIDS (Sao Paulo), and the Instituto Nacional de Salud Publica (Cuernavaca).

RESULTS

The HIM study biopsy cohort included 2754 men ages 18–73 years (median age, 32 years). In general, the majority of participants were <45 years of age, white, non-Hispanic, had ≤12 years of education, had never smoked, and were uncircumcised (Table 1). The median length of follow-up for men in the biopsy cohort was 12.4 months (interquartile range, 6.9–19.2 months). Within this cohort, a total of 377 EGLs in 228 men were pathologically confirmed. Of these, 198 men developed an incident EGL during the period of the biopsy cohort. These EGLs were primarily diagnosed as condyloma (n = 158) or suggestive of condyloma (n = 124), with PeIN lesions composing a smaller percentage of the overall diagnoses (n = 14).

Overall, the 12-month cumulative incidence of any EGL was higher among men <45 years of age (4.8% and 5.4% among men aged 18–30 and 31–44 years, respectively, and 2.6% among men aged 45–73 years; P = .030 across the entire follow-up period). The incidence of EGLs also varied by pathological diagnoses: 2.8 cases/100 person-years versus 0.2 cases/100 person-years for condyloma combined and PeIN, respectively. The 12-month cumulative incidence for the condyloma combined category decreased with age (3.8%, 3.4%, and 1.7% for ages 18–30, 31–44, and 45–73 years, respectively; P = .021 across the entire follow-up period). The 12-month cumulative incidence of PeIN also appeared to decrease with age, although this trend did not reach statistical significance over time (0.4%, 0.1%, and 0.0% for ages 18–30, 31–44, and 45–73 years, respectively; P = .238 across the entire follow-up period; Table 2 and Figure 1).

Overall, 291 (77.2%) of the total 377 EGLs identified in this study were HPV positive by INNO-LiPA (Table 3). High-risk genotypes were detected in 59 (15.6%) of EGLs, and low-risk types were detected in 276 (73.2%) of EGLs. Low-risk HPV types, predominantly HPV 6 and HPV 11, were detected primarily in lesions diagnosed as condyloma (79.7% tested positive for low-risk HPV, 49.4% tested positive for HPV 6, and 31.0% tested positive for HPV 11) or suggestive of condyloma (75.8% tested positive for low-risk HPV, 57.3% tested positive for HPV 6, and 18.5% tested positive for HPV 11). In contrast, high-risk HPV types were only detected in 8.2% and 13.7% of EGLs diagnosed as condyloma or suggestive of condyloma, respectively (Table 3). Among all EGLs, 269 (71.4% of all EGLs; 92.4% of HPV-positive EGLs) included ≥1 type targeted by the quadrivalent vaccine, and 282 (74.8% of all EGLs; 96.9% of HPV-positive EGLs) included ≥1 type targeted by the nonavalent vaccine. A total of 44 EGLs (11.7%), 5 of which were PeIN lesions, were characterized as HR/LR HPV.

Table 3.

Prevalence of Mucosal Human Papillomavirus (HPV) DNA Within the Tissue of Prevalent and Incident External Genital Lesions (EGLs) Among 228 Men in the HPV Infection in Men Study

| HPV Type | Pathology-Based Diagnosis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any EGLa (n = 377) | Condyloma (n = 158) | Suggestive of Condylomab (n = 124) | PeIN (n = 14) | Otherc (n = 81) | |

| Any type | 291 (77.2) | 129 (81.6) | 96 (77.4) | 14 (100.0) | 52 (64.2) |

| High-risk type | 59 (15.6) | 13 (8.2) | 17 (13.7) | 12 (85.7) | 17 (21.0) |

| 16 | 17 (4.5) | 2 (1.3) | 4 (3.2) | 8 (57.1) | 3 (3.7) |

| 18 | 3 (0.8) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| 31 | 8 (2.1) | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.9) |

| 33 | 3 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.5) |

| 35 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 39 | 7 (1.9) | 3 (1.9) | 2 (1.6) | 2 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| 45 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 51 | 21 (5.6) | 3 (1.9) | 8 (6.5) | 2 (14.3) | 8 (9.9) |

| 52 | 21 (5.6) | 6 (3.8) | 6 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (11.1) |

| 56 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 58 | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.2) |

| 59 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 68 | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Low-risk type | 276 (73.2) | 126 (79.7) | 94 (75.8) | 7 (50.0) | 49 (60.5) |

| 6 | 179 (47.5) | 78 (49.4) | 71 (57.3) | 2 (14.3) | 28 (34.6) |

| 11 | 95 (25.2) | 49 (31.0) | 23 (18.5) | 4 (28.6) | 19 (23.5) |

| 26 | 5 (1.3) | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.7) |

| 40 | 4 (1.1) | 2 (1.3) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.2) |

| 43 | 3 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.2) |

| 44 | 8 (2.1) | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.9) |

| 53 | 5 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.7) |

| 54 | 6 (1.6) | 2 (1.3) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.7) |

| 66 | 5 (1.3) | 2 (1.3) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.5) |

| 69/71 | 3 (0.8) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.5) |

| 70 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 73 | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| 74 | 19 (5.0) | 8 (5.1) | 6 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (6.2) |

| 82 | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.2) |

| Both high- and low-risk typesd | 44 (11.7) | 10 (6.3) | 15 (12.1) | 5 (35.7) | 14 (17.3) |

| Quadrivalent vaccine typee | 269 (71.4) | 124 (78.5) | 91 (73.4) | 12 (85.7) | 42 (51.9) |

| Nonavalent vaccine typef | 282 (74.8) | 129 (81.6) | 93 (75.0) | 12 (85.7) | 48 (59.3) |

Data are no. (%) of external genital lesions. DNA was detected using an HPV line-probe assay.

Abbreviation: PeIN, penile intraepithelial neoplasia (I–III).

a Pathologically confirmed EGL.

b Includes lesions suggestive but not diagnostic of HPV infection or condyloma.

c Includes various HPV-unrelated skin conditions, such as seborrheic keratosis and skin tags.

d Lesions with coinfections including ≥1 high-risk and ≥1 low-risk HPV type.

e Presence of ≥1 of the HPV genotypes targeted by the licensed quadrivalent vaccine (HPV 6, 11, 16, and 18).

f Presence of ≥1 of the HPV genotypes targeted by the nonavalent vaccine (HPV 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58).

All 14 of the PeIN lesions diagnosed in this cohort were positive for HPV, with 85.7% positive for ≥1 high-risk HPV genotypes. HPV 16 was found in 8 (57.1%) of the PeIN specimens. In contrast, low-risk types were only found in 50% of PeIN lesions (14.3% were positive for HPV 6, and 28.6% were positive for HPV 11; Table 3). While low-risk types were mainly found in PeIN lesions as coinfections with a high-risk genotype, HPV 6 was found as a single infection in 1 PeIN III lesion, and HPV 11 was found as a single infection in 1 PeIN I lesion (Table 4). All PeIN lesions were diagnosed in men <45 years of age, with 8 located on the penile shaft (Table 4). Two incident PeIN lesions contained only HPV types not targeted by either the quadrivalent or the nonavalent vaccine (HPV 39, 51, 68, and 73).

Table 4.

Human Papillomavirus (HPV)–Associated Penile Intraepithelial Neoplasia (PeIN) Lesions Diagnosed in the Biopsy Cohort of the HPV Infection in Men Study

| Age at Diagnosis, y | Biopsy Location | Pathology-Based Diagnosis | HPV Genotype(s)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| 26 | Shaft, left ventral | PeIN I | NA |

| 25 | Meatus | PeIN I | 11 |

| 37 | Coronal sulcus | PeIN I | 39, 68, 73 |

| 24 | Coronal sulcus | PeIN II | 11, 18, 39 |

| 24 | Shaft, right ventral | PeIN II | 51 |

| 26 | Right inguinal | PeIN II | 16 |

| 34 | Shaft, left dorsal | PeIN II | 16 |

| 35 | Shaft, right ventral | PeIN II | 6, 16 |

| 42b | Shaft, left ventral | PeIN II/III | 16 |

| 42b | Shaft, right ventral | PeIN II/III | 16 |

| 24 | Meatus | PeIN III | 6 |

| 26 | Glans penis | PeIN III | 16 |

| 27 | Shaft, left ventral | PeIN III | 11, 16 |

| 42 | Shaft, left dorsal | PeIN III | 16 |

Abbreviations: NA, not available-specimen insufficient for genotyping analysis; PeIN I, mild/low-grade squamous dysplasia; PeIN II, moderate squamous dysplasia; PeIN II/III, moderate squamous dysplasia with focal high-grade dysplasia; PeIN III, high-grade squamous dysplasia/carcinoma in situ.

a HPV genotyping results were obtained using an HPV line-probe assay with DNA extracted from a formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue biopsy specimen.

b Both specimens were from a single participant and underwent diagnostic analysis.

DISCUSSION

In this study, younger men (<45 years old) had the highest risk of developing an EGL, with the incidence of condyloma significantly decreasing with age. However, the EGL incidence did not fall to 0 among men aged 45–70 years, indicating that men remain susceptible to acquiring new HPV-related EGLs throughout the life span. The occurrence of PeIN only among those younger than 45 years is consistent with the concept that these lesions are precursors to penile cancers, which are primarily diagnosed in men ≥60 years of age [8].

Our primary HPV genotype-specific findings for condyloma and PeIN are consistent with previous literature reports: condyloma is primarily caused by low-risk types such as HPV 6 or 11 [9, 10], while PeIN is primarily associated with high-risk types, particularly HPV 16 [11]. However, it is of interest to note that 2 PeIN lesions in our study contained only a single low-risk genotype (HPV 6 or 11). The lone presence of a genotype that is generally considered nononcogenic in these precancerous lesions is consistent with prior published results in which other types of high-grade precancerous anogenital lesions, albeit rarely, were exclusively associated with a single low-risk HPV type [12, 13]. Further research is needed to rule out the possibility of low viral load presence of high-risk HPV genotypes and the clinical significance of HPV 6–related PeIN III, if indeed the lesion was caused by this HPV type.

A moderate increase in protection against EGLs in men is predicted with the nonavalent vaccine, compared with its quadrivalent counterpart, with an additional 4.5% of HPV-positive EGLs in this study harboring ≥1 of the 5 genotypes (HPV 31, 33, 45, 52, or 58) not included in the quadrivalent vaccine. The quadrivalent vaccine has demonstrated long-term immunogenicity in women against vaccine-related HPV and subsequent disease [14, 15], but similar studies have not yet been performed in men, nor have any studies accrued sufficient follow-up from which to draw conclusions regarding protection across decades. The continuous risk of EGLs across all age groups in this study emphasizes the need to explore male vaccination at older ages and to ensure that vaccine-related immunity is retained across the life span of males.

Strengths of this study include the size and multinational nature of the cohort and the occurrence of study visits every 6 months to allow for early detection of lesions; in fact, as lesions suggestive of condyloma had a similar HPV prevalence and type distribution as those diagnosed as condyloma, these may have been diagnosed before they had a chance to fully develop to condyloma. This may have also prevented us from inadvertently excluding lesions that would have self-resolved over a longer period, enabling us to have a more complete understanding of all EGLs resulting from HPV infection. Another strength includes the use of biopsy tissue for genotyping, as the biopsy results have been shown to accurately reflect the HPV genotypes found within these lesions [5]. Potential limitations of this study include the small sample size for PeIN, owing to the rarity of this type of lesion. Differences in collection and diagnosis of lesions may have also varied between countries and pathologists, although the clinical procedures and the pathology panel were designed to minimize discrepancies. While the HPV prevalence in condyloma, particularly of low-risk types 6 and 11, was found to be ≥90% in a number of previous studies [2, 16–18], differences may also be attributed to variations by sex, country (affecting circulating types), and DNA extraction and HPV genotyping methods.

The data presented here are the first results from a large, prospective cohort of men with regard to development of EGLs by genotype and age, laying the groundwork for subsequent studies of other risk factors that may contribute to HPV-related lesion development among men. Ongoing collection of EGL specimens through the HIM study and other male and female cohort studies will likely continue to shape our understanding of the role of specific HPV genotypes in EGL development, including potential interactions between multiple types within a single lesion and the mechanism by which low-risk HPV types contribute to development of precancerous lesions.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank the HIM Study teams and participants in the United States (Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa), Brazil (Centro de Referência e Treinamento em DST/AIDS, Fundação Faculdade de Medicina Instituto do Câncer do Estado de São Paulo, Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, São Paulo), and Mexico (Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública, Cuernavaca).

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (grant R01 CA098803 to A. R. G.) and the American Cancer Society (postdoctoral fellowship PF-13-222-01-MPC to C. M. P. C.).

Potential conflicts of interest. A. R. G. is a current recipient of grant funding from Merck (IISP39582). and A. R. G. and L. L. V. are members of the Merck Advisory Board. J. A. M. receives personal fees from Myriad. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Crispen PL, Mydlo JH. Penile intraepithelial neoplasia and other premalignant lesions of the penis. Urol Clin North Am. 2010;37:335–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forman D, de Martel C, Lacey CJ, et al. Global burden of human papillomavirus and related diseases. Vaccine. 2012;30(suppl 5):F12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giuliano AR, Palefsky JM, Goldstone S, et al. Efficacy of quadrivalent HPV vaccine against HPV Infection and disease in males. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:401–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giuliano AR, Lee JH, Fulp W, et al. Incidence and clearance of genital human papillomavirus infection in men (HIM): a cohort study. Lancet. 2011;377:932–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62342-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anic GM, Messina JL, Stoler MH, et al. Concordance of human papillomavirus types detected on the surface and in the tissue of genital lesions in men. J Med Virol. 2013;85:1561–6. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giuliano AR on behalf of the V503-001 and -002 study teams. Abstracts of the EUROGIN Congress—HPV at a Crossroads: 30 Years of Research and Practice. Safety and tolerability of a novel 9-valent HPV L1 virus-like particle vaccine in boys/girls age 9–15 and women age 16–26 [abstract SS 8-7]; Florence, Italy). 2014. p. 103. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joura E on behalf of the V503-001 study team. Abstracts of the EUROGIN Congress—HPV at a Crossroads: 30 Years of Research and Practice. Efficacy and immunogenicity of a novel 9-valent HPV L1 virus-like particle vaccine in 16- to 26-year-old women [abstract SS 8-4]; Florence, Italy. 2013. p. 102. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baldur-Felskov B, Hannibal CG, Munk C, Kjaer SK. Increased incidence of penile cancer and high-grade penile intraepithelial neoplasia in Denmark 1978–2008: a nationwide population-based study. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:273–80. doi: 10.1007/s10552-011-9876-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawkins MG, Winder DM, Ball SL, et al. Detection of specific HPV subtypes responsible for the pathogenesis of condylomata acuminata. Virol J. 2013;10:137. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan PK, Luk AC, Luk TN, et al. Distribution of human papillomavirus types in anogenital warts of men. J Clin Virol. 2009;44:111–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernandez BY, Goodman MT, Unger ER, et al. Human papillomavirus genotype prevalence in invasive penile cancers from a registry-based United States population. Front Oncol. 2014;4:9. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guimera N, Lloveras B, Lindeman J, et al. The occasional role of low-risk human papillomaviruses 6, 11, 42, 44, and 70 in anogenital carcinoma defined by laser capture microdissection/PCR methodology: results from a global study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1299–310. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31828b6be4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cornall AM, Roberts JM, Garland SM, Hillman RJ, Grulich AE, Tabrizi SN. Anal and perianal squamous carcinomas and high-grade intraepithelial lesions exclusively associated with “low-risk” HPV genotypes 6 and 11. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:2253–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castellsague X, Munoz N, Pitisuttithum P, et al. End-of-study safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of quadrivalent HPV (types 6, 11, 16, 18) recombinant vaccine in adult women 24–45 years of age. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:28–37. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luna J, Plata M, Gonzalez M, et al. Long-term follow-up observation of the safety, immunogenicity, and effectiveness of Gardasil in adult women. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ball SL, Winder DM, Vaughan K, et al. Analyses of human papillomavirus genotypes and viral loads in anogenital warts. J Med Virol. 2011;83:1345–50. doi: 10.1002/jmv.22111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernandez-Suarez G, Pineros M, Vargas JC, et al. Human papillomavirus genotypes in genital warts in Latin America: a cross-sectional study in Bogota, Colombia. Int J STD AIDS. 2013;24:567–72. doi: 10.1177/0956462412474538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aubin F, Pretet JL, Jacquard AC, et al. Human papillomavirus genotype distribution in external acuminata condylomata: a Large French National Study (EDiTH IV) Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:610–5. doi: 10.1086/590560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]