Atypical haemolytic-uraemic syndrome (aHUS) is a disease of uncontrolled complement alternative pathway activation. Eculizumab induces terminal complement blockade (TCB), and is safe and effective for aHUS treatment as evidenced by its recent approval by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Commission.

A 26-year-old woman was admitted 1 week after her first childbirth for aHUS with creatinine 6.2 mg/dL (550 µmol/L), haemoglobin 3.6 g/dL (36 g/L), lactate dehydrogenase 2155 U/L (upper normal limit 248), 9% schizocytes and platelet count 49 × 103/µL (49 × 109/L). She had a medical history of Crohn's disease 5 years earlier and a skin melanoma 3 years earlier. Family history was remarkable with her father's brother presenting two renal graft losses related to aHUS despite plasma exchange (PE). The patient and her uncle both carried combined heterozygous mutations in genes coding for Factor H (p.Lys1186Thr) and Factor I (p.Ile322Thr).

Daily PE was started with 60 mL/kg fresh frozen plasma substitution for 80 kg body weight with an initial positive haematological response without improvement of renal function requiring haemodialysis. Due to family history and suspected genetic background that was confirmed later, the patient was switched to eculizumab [1–3], 900 mg on Day 3 post-admission (PA). Placental retention was subsequently diagnosed and treated but a second 900 mg eculizumab infusion 10 days-PA was not effective in controlling aHUS (decreasing platelet count). Daily PE was re-started without supplemental eculizumab.

During eculizumab treatment, complement activity measured with a validated sensitized sheep erythrocytes lysis assay (CH50) is expected to be <10% as observed in hereditary C5 deficiency [4]. We considered that complete TCB would be achieved for a serum CAE (complement activation enzyme immunosorbent assay, Diasorin®) [5] value <0.5 U/mL, (normal range 63–145 U/mL), corresponding to CH50 <10%. Patient serum CAE was 77 U/mL before the first eculizumab administration. Following the first three eculizumab administrations, complete TCB was maintained for a maximum of 4 days. On Day 39-PA, because of a continuous drop in platelet count from 161 to 81 × 103/µL despite intensive PE and as other causes of thrombocytopenia than aHUS were ruled out, eculizumab was resumed at a higher dose (1200 mg) and administrated whenever CAE activity increased over 0.5 U/mL.

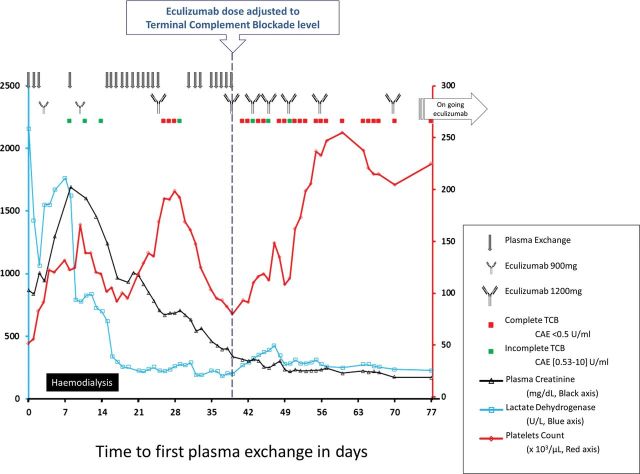

Under complete and sustained TCB, the outcome was rapidly positive (Figure 1): blood count normalized and the patient recovered normal renal function [serum creatinine stabilized to 0.8 mg/dL(75 µmol/L) without proteinuria after 6 months-PA] on the approved eculizumab dosing regimen. Far from aHUS trigger, eculizumab was tapered from 18 months-PA, and the patient had no signs of aHUS at the last follow-up 2 months after interrupting eculizumab.

Fig. 1.

Treatment regimen and clinical course of a patient with complement factor H and complement factor I gene mutations presenting post-partum (aHUS). Time is represented from the day of admission that corresponded to the first PE. Patient was switched to eculizumab on Day 3 but the platelet count expected improvement was not observed and PE was restarted few days after the first three doses without supplemental eculizumab dosing after each session. During eculizumab therapy, TCB was measured using the CAE assay. On Day 39, the patient was considered plasma-exchange resistant and thereafter eculizumab administration was decided each time CAE was increasing over 0.5 UI/mL (green spot). Until Day 50, TCB was sustained for a maximum of only 3 to 4 days after each dose; therefore, the patient received eculizumab twice weekly. From Day 56, eculizumab administered according to the approved dose regimen of every 14 days resulted in favourable haematological and renal outcomes.

This is the first case of post-partum aHUS treated with eculizumab and the first description of TCB functional assessment to guide eculizumab dose and frequency of administration so as to obtain permanent complete complement blockade. This pragmatic therapeutic option seems to be adequate to rescue acute phases of aHUS, when the expected improvement does not occur under the recommended dose regimen of eculizumab. The degree of uncontrolled complement activation likely is influenced by the genetic background and the magnitude of the biological stress such as post-partum status [2, 6].

Conflict of interest statement

Alexion honoraria: C.L. for lectures and expert testimony, V.F.B. and C.C. for consultancy. Y.D. and C.B. have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Olivier Gerbouin, Pharmacist, the nurses of the Nephrology Department and the technicians of the Immunology Laboratory for their valuable help. We are also grateful to the Alexion physician team for providing eculizumab.

References

- 1.Lapeyraque AL, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Robitaille P. Efficacy of eculizumab in a patient with factor-H-associated atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:621–624. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1719-3. doi:10.1007/s00467-010-1719-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noris M, Caprioli J, Bresin E, et al. Relative role of genetic complement abnormalities in sporadic and familial aHUS and their impact on clinical phenotype. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1844–1859. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02210310. doi:10.2215/CJN.02210310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sellier-Leclerc AL, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Dragon-Durey MA, et al. Differential impact of complement mutations on clinical characteristics in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2392–2400. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006080811. doi:10.1681/ASN.2006080811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aguilar-Ramirez P, Reis ES, Florido MP, et al. Skipping of exon 30 in C5 gene results in complete human C5 deficiency and demonstrates the importance of C5d and CUB domains for stability. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:2116–2123. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.10.035. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2008.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaskowski TD, Martins TB, Litwin CM, et al. Comparison of three different methods for measuring classical pathway complement activity. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:137–139. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.1.137-139.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fakhouri F, Roumenina L, Provot F, et al. Pregnancy-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome revisited in the era of complement gene mutations. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:859–867. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009070706. doi:10.1681/ASN.2009070706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]