Abstract

Purpose

To investigate patterns in pharmacological treatment for patients with schizophrenia, we examined antipsychotic polypharmacy across multiple outpatient healthcare settings and their association with hospital admission.

Methods

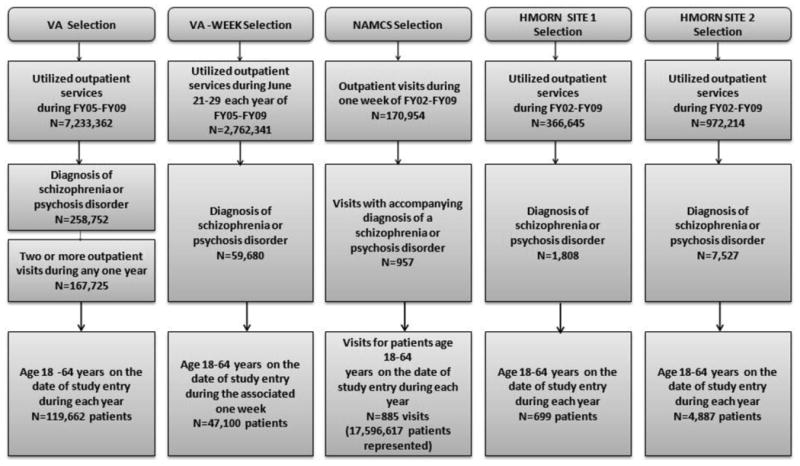

This multi-system study utilized data on patients diagnosed with schizophrenia, including 119,662 Veterans in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system, 553 and 4,887 patients in two private, integrated health systems (HMO), and outpatients (17,596,617 visits in 1-week look-back) from a nationally representative sample of U.S. residents seeking care outside federal systems (National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, NAMCS). Antipsychotic polypharmacy was defined as the use of more than one antipsychotic agent during the covered period (week, year). The prevalence and trend of antipsychotic polypharmacy was assessed in each system (2002-2009 or 2005-2009) and their association with one-year hospital admission using multivariable logistic regression.

Results

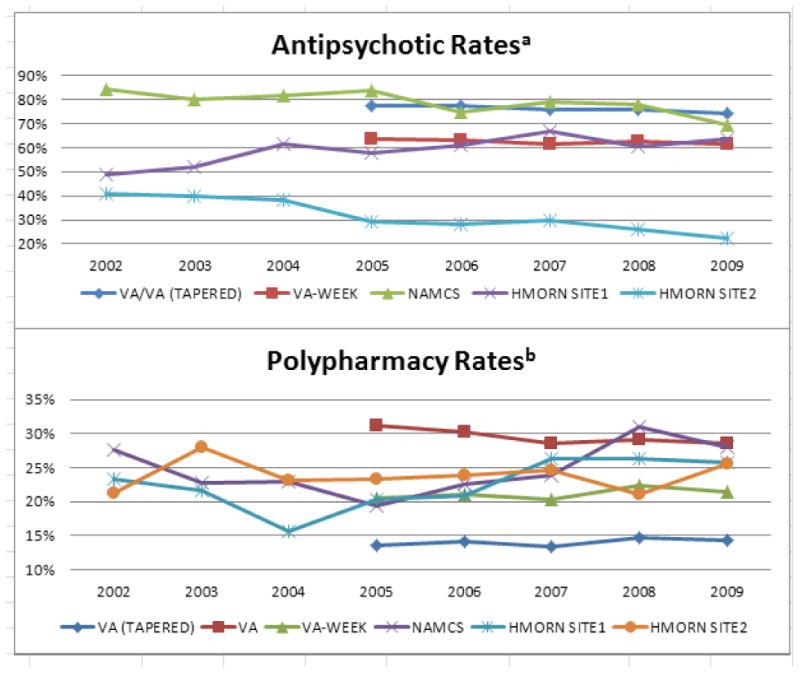

Annual antipsychotic treatment in the VA ranged 74-78% each year, with the lowest rates observed in the HMO (49-67% site 1, 22-41% site 2) per pharmacy fill data; NAMCS ranged 69-84% per clinician-reported prescriptions. Polypharmacy rates depended on the defined covered period. The VA had lower polypharmacy rates when data were restricted to the one-week covered period used in non-federal systems (20-22% vs. 19-31% NAMCS). In each system, polypharmacy was associated with increased odds of admission (odds ratio ranging 1.4-2.4).

Conclusions

The unadjusted longitudinal trends suggest tremendous system variations in antipsychotic use among patients with schizophrenia. Cross-system comparisons are inherently subject to uncertainty due to variation in the amount and type of data collected. Given the current debate over healthcare access and costs, electronic systems to signal polypharmacy could assist in identifying patients requiring more complex clinical and pharmacy management, individuals at substantially higher risk for adverse events. Such enhanced sentinel detection and follow-up care could ultimately lead to improved clinical practice and fiscal well-being.

Keywords: schizophrenia, antipsychotics, polypharmacy, Veterans, health care systems

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a complicated mental illness requiring lifelong treatment with antipsychotic drugs.1 Schizophrenia imparts social and cognitive impairment, pervasively affecting memory, attention, motor skills, executive functioning and intelligence.2 Continuous use of antipsychotic drugs is recommended, uniquely for schizophrenia among major mental illnesses. Although antipsychotic monotherapy is the standard approach for managing symptoms of schizophrenia,3-6 multiple antipsychotic medications may be prescribed. Several factors contribute to pharmacological treatment patterns in caring for patients with schizophrenia, including patient-level issues, provider prescribing decisions, health system culture, and organizational structure.7 Given the challenges and costs of treating individuals with schizophrenia, the prescribing trends of antipsychotic monotherapy and polypharmacy may vary across healthcare systems.

A number of international guidelines recommend antipsychotic monotherapy, using second-generation antipsychotics (SGA) as first-line medications for the treatment of schizophrenia.4,8-13 While first-generation antipsychotics are acceptable in terms of efficacy, they may be avoided or considered second-line treatment because of their irreversible adverse effects (e.g., tardive dyskinesia).14,15 However, antipsychotic polypharmacy, defined as the concurrent use of more than one antipsychotic drug for a single clinical condition, is increasingly prescribed. 16,17 Indeed, since 1996, studies have shown the rate of antipsychotic polypharmacy has increased among patients with schizophrenia, with the extent of polypharmacy varying by the populations under study, the treatment setting, and how antipsychotic polypharmacy was defined and measured.18 Specifically, high rates of antipsychotic polypharmacy among both outpatients and inpatients with schizophrenia have been reported: (1) up to 20% for patients receiving care in the Department of Veterans Affairs in fiscal year 2000; 19 (2) 35% for outpatients in the public mental health system during the 2-year period 1996-1998;20 (3) up to 40% of outpatients in Medicaid claims data in 1998-2000;16 and (4) 38-55% of inpatients in Asian countries from 2001-2009.21,22 Some plausible reasons for these figures include patient or clinician dissatisfaction with treatment effects, bothersome side effects, or undetected poor adherence leading to persistent symptoms that are incorrectly attributed to ineffective pharmacotherapy. Nonetheless, prescribing multiple antipsychotics may result in adverse outcomes, such as emergency department visits from adverse drug reactions or psychiatric admissions,23 while also increasing direct treatment costs for the system, metabolic disturbance, indirect societal burden and impaired quality of life for the patient.24-26

Few studies have assessed the differential longitudinal prevalence of polypharmacy between healthcare systems for patients with schizophrenia. Most studies examined broad antipsychotic polypharmacy rates across countries,27,28 although one older study compared combinations of psychotropic drugs targeting the same set of symptoms (acute paranoid schizophrenia) in California, New York, Pennsylvania, and Texas based upon a survey of psychiatrists.29 To the best of our knowledge, only two studies have compared pharmacotherapy for patients with schizophrenia across multiple types of healthcare systems.30,31 In the first study of national data, patients with schizophrenia treated in the Department of Veterans Affairs healthcare system were more likely to receive an antipsychotic medication and more likely to be dosed above treatment recommendations than in the private sector. However, it did not appear that physical comorbidities were included for case-mix adjustment or that longitudinal pharmacologic patterns were measured.30 The second study, using data from 1994-1996, found that outpatients receiving care in the Veterans Health Administration in two states were less likely to receive an antipsychotic medication than patients outside of this system.31 Despite these prior studies, no large-scale multi-system studies have investigated this issue in the last decade. With the growing national concern regarding increased polypharmacy prescribing for patients with schizophrenia, coupled with concern over the high cost of duplicative or non-evidence-based treatment (or excess emergency department or inpatient care costs), new data are needed to inform policy and clinical decisions.

In this study, we compared longitudinal data on antipsychotic prescribing and polypharmacy among patients diagnosed with schizophrenia in multiple healthcare systems representing different organizational structures: 1) the nationwide Veterans Health Administration, the Department of Veterans Affairs' health care system (VA); 2) non-federal outpatient settings nationwide; and 3) two large not-for-profit healthcare systems in the southwestern and Great Lakes areas of the United States. We also modeled one-year hospital admission as a function of polypharmacy (versus monotherapy), adjusting for patient characteristics and disease burden. As an additional methodological aim, we examined how the availability of different amounts of data, depending on the source of information, affected the apparent rates of antipsychotic prescribing and polypharmacy.

Methods

This study utilized a retrospective design relying on several sources of data, including a public use dataset and data from multiple healthcare systems for which approval was obtained from the respective institutional review boards (IRB). Patients were 18-64 years old on the date of study entry and were diagnosed with schizophrenia or an unspecified psychotic disorder. These disorders were defined by ICD-9-CM codes from the medical record (295 excluding 295.5 latent [used for persons with symptoms but no psychotic episode before a schizophrenia diagnosis can be definitively assigned]; or 298.9). The unspecified psychotic disorder code was included when it was determined that one healthcare system did not typically employ the 295 codes but used 298.9 instead. The latent schizophrenia code was rare, appearing on the records of 135 VA patients, all of whom also had other codes for schizophrenia; the use of 295.5 may be an error. No cases were noted in the other data sources. Elderly patients were excluded to reduce the impact of “burn-out” in older patients with schizophrenia as these patients typically have few positive symptoms, derive little benefit from antipsychotics, may be at increased risk of death from antipsychotics, and are therefore less likely to be prescribed antipsychotics.32,33

National Representative Sample (NAMCS)

The public use dataset was obtained from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) to represent nationwide non-federal healthcare utilization for patients with schizophrenia during fiscal year 2002 (FY02; Oct. 2001-Sep. 2002) through FY09.34 NAMCS data contain information on non-federal office-based physician visits obtained through sampling a set of clinics and requesting these clinics to report on a systematic random sample during a single week of patient visits. A total of 885 visits over 8 years representing more than 17 million community-based outpatients diagnosed with schizophrenia or a psychotic disorder were identified from this national sample. Clinicians responding to this survey provided answers based on the past week at their practice. Pharmacy fill data are not assessed by the NAMCS survey although the survey does collect clinician-reported prescription medications.

National Federal Sample (VA)

For study inclusion, patients receiving VA care must have had two or more outpatient dates of care for which a diagnosis of schizophrenia or psychotic disorder was recorded with the same ICD-9-CM code. Data were only available for VA patients in the years 2005-2009 due to IRB approvals. VA data were extracted from the VA's all-electronic medical records system for patients treated during FY05-FY09. For the VA cohort, we obtained data on all 119,662 veterans diagnosed with schizophrenia or psychotic disorder system-wide. Similar to the NAMCS data, the VA sample entailed rolling enrollment (new patients enter the cohort each year with some overlapping cases). The major difference between VA and NAMCS healthcare settings was that VA data captured year-round health care utilization and pharmacy fills per patient rather than one week of data. It is unclear from NAMCS methods how far back into the patient chart the survey responses reach. Thus, for comparability we also assessed one week (June 21-June 28, per year analyzed) of use for VA patients during each fiscal year in order to resemble NAMCS data, identifying 47,100 patients (VA-WEEK).

Private Healthcare Systems (HMORN)

For the private, not-for-profit health care systems, we used data from two sites (site 1 and site 2) of the Health Maintenance Organization Research Network (HMORN) Virtual Data Warehouse. The HMORN is a federation of 19 care-and-coverage healthcare systems that have developed a set of standardized data definitions in order to create uniform health care measures from member data, primarily health care claims, from the year 2000 onward.35-37 We identified 699 patients at site 1 and 4,887 patients at site 2 diagnosed with schizophrenia or psychotic disorder during FY02-FY09. There were insufficient numbers for a meaningful one-week look-back.

Measures

Within each system of care (NAMCS, VA, and HMORN), patient demographic characteristics were obtained: age at baseline, gender, race, and ethnicity. Age was used to create a variable representing a decade effect in the proposed models, and ethnicity was dichotomously defined as Hispanic (yes/no). Case-mix adjusters included Charlson comorbidity score and the Selim total comorbidity score (physical and mental), with comorbidity indices calculated at patients' first year of entry. The Charlson comorbidity sums weighted indicators (with weights ranging from 1-6) of 19 conditions associated with post-hospitalization one year mortality,38 and the Selim sums indicators of 30 chronic physical illnesses and 6 mental health conditions.39 Both the Charlson and Selim scores are commonly used to adjust for case-mix. There is some overlap in codes (e.g., some cancer, diabetes and cardiovascular diagnosis codes), however, the two case-mix adjusters can be used together because they capture different aspects of disease burden. Shared variance between these summary measures produced a correlation of 0.53 (28% shared variance) in a recent study conducted with a chronically ill cohort of Veterans.40

Antipsychotic drugs were classified as either first-generation (chlorpromazine or promazine, fluphenazine, haloperidol, mesoridazine, molindone, perphenazine, thioridazine, thiothixene, trifluoperazine, pimozide, loxapine, prochlorperazine, droperidol, and chlorprothixene) or second-generation agents (aripiprazole, clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, ziprasidone, paliperidone, and asenapine). The main outcome of interest was the rate of antipsychotic polypharmacy, which was assessed each year and defined as having filled prescriptions for two or more antipsychotic medications concurrently in a year, or in one week in VA-WEEK sample. In addition to using complete VA utilization data and one-week utilization data to define polypharmacy, a third method of analysis employed tapered polypharmacy. Tapered polypharmacy acknowledges that clinicians may want patients to switch drugs, for example from risperidone to aripiprazole. Tapered polypharmacy for VA outpatients (VA TAPERED) was defined as before but allowed up to 60 days overlap in refill periods. This approach accommodates the practice of gradually decreasing the dose of a drug being discontinued while gradually increasing the dose of the drug being substituted. These cases would not be considered polypharmacy as they represent a planned transition from one antipsychotic to another. In the other data sources, we were unable to determine whether concurrent use represented tapering off one medication and onto another or intentional, ongoing use of two or more antipsychotics. A secondary outcome was the proportion of patients across systems prescribed any antipsychotic medication each year. Finally, we examined one-year all-cause hospitalization as an outcome.

Analysis Plan

Means and frequencies were calculated describing patient characteristics for each unique system data source. Analyses were performed in SAS, version 9.2 (© SAS Inc, Cary, NC), with survey procedures used for the NAMCS weighted data.41 To compare yearly prevalence and trends of antipsychotic polypharmacy, we first determined the proportion of patients with schizophrenia who received any antipsychotic medication and then the proportion of those taking antipsychotics who received antipsychotic polypharmacy. Logistic regression was employed. For each healthcare system, we modeled antipsychotic polypharmacy (vs. monotherapy) among patients prescribed antipsychotics as a function of patient characteristics. In these models, the outcome was polypharmacy during the one week of utilization for patients in the one-week data models (VA-WEEK and NAMCS) and polypharmacy during the year following study entry in the remaining models (VA TAPERED, non-tapered, HMORN sites 1 and 2). The relative odds of receiving antipsychotic polypharmacy were estimated as a function of demographic covariates and first year in the study. Patients with first entrance year in FY09 were excluded from the multivariable models since one-year follow-up polypharmacy could not be measured. Logistic regression also modeled risk of one-year hospital admission for each healthcare system separately, adjusting for patient characteristics. A maximum type I error rate of α = 0.05 was applied to all analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics among the four systems are displayed in Table 1. Among the 119,662 VA patients with schizophrenia, only 7% were women, whereas women accounted for 45% of the estimated NAMCS sample, 51% of the HMORN site 1 sample of 699 patients and 49% of the HMORN site 2 sample of 4,887 patients. VA patients were older with a mean age of 50.6 years (SD = 8.8) compared to 43.3 years (SD = 12.2) for NAMCS, 40.5 (SD = 14.9) for HMORN site 1 and 41.3 (SD=12.7) for HMORN site 2. Both the Charlson comorbidity score and Selim comorbidity index were higher among VA patients than non-VA patients. Race differed by sample. African Americans were more numerous in the VA and HMORN site 2 samples (34% VA and 52% site 2 vs 21% NAMCS and 14% site 1). Hispanic ethnicity was more common among VA, NAMCS and HMORN site 1 patients compared to site 2 (7% VA, 6% NAMCS, 3% site 1 vs. 1% site 2). For the 47,100 VA patients in the one-week sample, descriptive statistics were very similar to the VA patients as a whole with slightly lower proportion Hispanic.

Table 1. Characteristics of Schizophrenia Patients in Four Health Care Settings: Veterans Health Administration (VA), National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), and Two HMO Research Network Sites (HMORN).

| Characteristics | VA (N=119,662) FY05-FY09 |

VA-WEEK (N=47,100) FY05-FY09 |

NAMCS (N=885) FY02-FY09 |

HMORN SITE 1 (N=699) FY02-FY09 |

HMORN SITE 2 (N=4,887) FY02-FY09 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| Age in years | 50.6 ± 8.8 | 51.5 ± 8.5 | 43.3 ± 12.2 | 40.5 ± 14.9 | 41.3 ± 12.7 |

| Selim Mental | 1.9 ± 1.1 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 1.2 ± 0.7 | 1.1 ± 0.9 | 1.5 ± 1.0 |

| Selim Physical | 1.9 ± 1.7 | 0.3 ± 0.8 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 1.7 | 1.2 ± 1.8 |

| Selim Total a | 3.8 ± 2.2 | 1.5 ± 1.0 | 1.3 ± 0.8 | 2.4 ± 1.8 | 2.7 ± 2.2 |

| Charlson | 0.8 ± 1.5 | 0.2 ± 0.6 | 0.1 ± 0.5 | 0.8 ± 1.8 | 0.6 ± 1.5 |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 8,331 (7.0) | 3,487 (7.4) | 401 (45.2) | 362 (51.8) | 2,391 (48.9) |

| Male | 111,331 (93.0) | 43,613 (92.6) | 484 (54.8) | 337 (48.2) | 2,496 (51.1) |

| Race | |||||

| White | 69,290 (57.9) | 27,768 (59.0) | 663 (74.1) | 472 (67.5) | 2,043 (41.8) |

| Black | 40,857 (34.1) | 16,138 (34.2) | 177 (21.4) | 96 (13.7) | 2,565 (52.5) |

| Other | 3,225 (2.7) | 1,345 (2.9) | 45 (4.5) | 11 (1.5) | 126 (2.6) |

| Unknown | 6,290 (5.3) | 1,849 (3.9) | 0 (0.0) | 120 (17.2) | 153 (3.1) |

| Hispanic | |||||

| Yes | 8,197 (6.8) | 2,958 (6.3) | 58 (6.6) | 19 (2.7) | 54 (1.1) |

| No | 105,175 (87.9) | 42,293 (89.8) | 767 (86.7) | 347 (49.6) | 1,230 (25.2) |

| Unknown | 6,290 (5.3) | 1,849 (3.9) | 60 (6.8) | 333 (47.6) | 3,603 (73.7) |

| Antipsychotic Types b | |||||

| None | 38,478 (32.2) | 18,536 (39.4) | 196 (22.1) | 361 (58.1) | 3308 (78.1) |

| First Only | 8,979 (7.5) | 3,747 (8.0) | 118 (13.3) | 17 (2.7) | 81 (1.9) |

| Second Only | 47,774 (39.9) | 19,324 (41.0) | 395 (44.6) | 177 (28.5) | 616 (14.5) |

| First & Second | 9,830 (8.2) | 2,621 (5.6) | 81 (9.2) | 21 (3.4) | 48 (1.1) |

| 2 or more Second | 14,601 (12.2) | 2,872 (6.1) | 95 (10.7) | 45 (7.2) | 182 (4.3) |

The Selim total index ranges from 0-36 (Selim Physical, range: 0-30; Selim Mental, range: 0-6); higher scores indicate more chronic physical and mental illness. The Charlson comorbidity score ranges from 0-37 with higher scores indicating greater risk of one-year post-discharge mortality.

The assessment of antipsychotic types was limited to patients with 1-year of available follow-up data after enrollment for VA, HMORN SITE 1, and HMORN SITE 2; antipsychotic types were measured in a 1-week period for VA-WEEK and NAMCS.

Prevalence of Antipsychotic Use and Polypharmacy

Trends over time in the use of antipsychotics and in antipsychotic polypharmacy for patients with schizophrenia prescribed antipsychotic medications are depicted in Figure 1. The table describes prescribing patterns in each system of care, including the VA sampled one-week of care and tapered polypharmacy. Overall, the proportion of VA patients having schizophrenia and prescribed some form of antipsychotic pharmacological treatment stayed fairly consistent during FY05-FY09 with 74% to 78% each year. The VA one-week sample had a stable trend with lower antipsychotic rates (62%-64%) each year. Across all healthcare systems, NAMCS had the highest antipsychotic rates (84%, 79% and 78%) in FY05, FY07 and FY08 while VA whole sample had the highest antipsychotic rates in FY06 (77%) and FY09 (74%). HMORN site 2 had the lowest antipsychotic rates (22%-30%) from FY05-FY09. In contrast, non-VA estimates of antipsychotic use revealed much greater variability across the same years, ranging from 69% to 84% for NAMCS and from 49% to 67% for HMORN site 1, and HMORN site 2 had the lowest rates with 22% to 41%. In addition, taking antipsychotics was more prevalent in nationwide systems (VA and NAMCS) than in the private, not-for-profit health care systems (HMORNs). For patients taking antipsychotics, the VA cohorts demonstrated relatively consistent polypharmacy prevalence for the years FY05-FY09: 13%-15% for tapered, 29%-31% for non-tapered and 20%-22% for the sampled one-week. Conversely, the non-federal national sample from NAMCS estimated a fluctuating polypharmacy trend during the respective years (19%-31%), while the non-national samples from HMORN also demonstrated more variable polypharmacy rates (16%-26% site 1 and 21%-26% site 2).

Figure 1. Antipsychotic and Polypharmacy Rates among Patients with Schizophrenia in Four Health Care Settings: Veterans Health Administration (VA), National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), and Two HMO Research Network Sites (HMORN).

a Among patients with schizophrenia who had visits in that year period.

b Among patients with schizophrenia who received an antipsychotic and had visits in that year period.

Multivariable Models of Antipsychotic Polypharmacy across Systems

The results of the multivariable logistic regression models comparing patient characteristics associated with antipsychotic polypharmacy are reported in Table 2 along with results from the various approaches to defining polypharmacy within the VA sample. Significant associations were not observed in the national non-federal settings (NAMCS). However, younger age (modeled in decades) was associated with increased odds of antipsychotic polypharmacy in VA non-tapered model and VA one-week model (OR = 0.79, 95% CI: 0.78-0.81 one-year; and OR = 0.91, 95% CI: 0.88-0.94 one-week). The odds ratios of 0.69 and 0.82 for age in the HMORN systems of care correspond to approximately 31% and 18% lower relative odds of polypharmacy for each decade of older age for sites 1 and 2, respectively. For all VA patients with schizophrenia, increased odds of antipsychotic polypharmacy were also observed for female veterans with the non-tapered method (OR = 1.11, 95% CI: 1.05-1.18). Greater total comorbidity per Selim was associated with increased risk of polypharmacy among all VA patients (OR = 1.09, 95% CI: 1.08-1.09) and patients in both HMORN sites (OR = 1.46, 95% CI: 1.15-1.86 site 1; OR=1.13, 95% CI: 1.04-1.23 site 2), indicating an approximate 9%, 46%, and 13% cumulative increased odds per additional chronic illness, respectively; but decreased risks of polypharmacy were observed for VA tapered sample (OR=0.97 per additional Selim condition, 95% CI: 0.96-0.98) and VA one-week sample (OR=0.94 per additional Selim condition; 95% CI: 0.91-0.97). Yet, the Charlson comorbidity score was associated with polypharmacy only for the VA tapered approach (OR=1.04, 95% CI: 1.02-1.06).

Table 2. Factors Associated with Antipsychotic Polypharmacy (vs. Monotherapy) among Patients with Schizophrenia across Four Systems: Veterans Health Administration (VA), National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), and Two HMO Research Network Sites (HMORN).

| Characteristics a | VA (TAPERED) | VA | VA-WEEK | NAMCS | HMORN SITE 1 | HMORN SITE 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) |

P-Value | OR (95% CI) |

P-Value | OR (95% CI) |

P-Value | OR (95% CI) |

P-Value | OR (95% CI) |

P-Value | OR (95% CI) |

P-Value | |

| Age (in decades) | 0.98 (0.95,1.00) |

0.082 | 0.79 (0.78,0.81) |

<0.001 | 0.91 (0.88,0.94) |

<0.001 | 0.84 (0.69,1.02) |

0.074 | 0.69 (0.54,0.89) |

0.004 | 0.82 (0.73,0.93) |

0.002 |

| Female | 1.07 (0.99,1.16) |

0.105 | 1.11 (1.05,1.18) |

<0.001 | 0.93 (0.83,1.04) |

0.193 | 1.0 (0.67,1.61) |

0.876 | 1.08 (0.58,2.03) |

0.812 | 1.23 (0.89,1.68) |

0.211 |

| FY02 | 0.83 (0.35,1.98) |

0.679 | 0.99 (0.39,2.51) |

0.977 | 0.82 (0.45,1.48) |

0.509 | ||||||

| FY03 | 0.69 (0.25,1.91) |

0.233 | 0.56 (0.18,1.73) |

0.314 | 1.17 (0.62,2.23) |

0.631 | ||||||

| FY04 | 0.70 (0.25,1.91) |

0.484 | 0.42 (0.13,1.35) |

0.144 | 0.97 (0.48,1.92) |

0.926 | ||||||

| FY05 | 1.61 (1.46,1.77) |

<0.001 | 1.12 (1.05,1.19) |

<0.001 | 1.35 (1.23,1.47) |

<0.001 | 0.60 (0.30,1.18) |

0.137 | 0.40 (0.11,1.51) |

0.177 | 1.10 (0.56,2.16) |

0.784 |

| FY06 | 0.96 (0.85,1.08) |

0.469 | 0.91 (0.84,0.98) |

0.010 | 0.54 (0.48,0.60) |

<0.001 | 0.68 (0.27,1.76) |

0.430 | 0.73 (0.24,2.18) |

0.568 | 0.93 (0.46,1.89) |

0.837 |

| FY07 | 0.90 (0.79,1.03) |

0.110 | 0.96 (0.88,1.04) |

0.274 | 1.01 (0.91,1.13) |

0.838 | 0.75 (0.37,1.53) |

0.432 | 1.09 (0.37,3.17) |

0.878 | 1.31 (0.66,2.61) |

0.440 |

| Charlson (range:0-37) | 1.04 (1.02,1.06) |

<0.001 | 0.99 (0.98,1.00) |

0.113 | 1.00 (0.94,1.06) |

0.975 | 0.55 (0.21,1.45) |

0.228 | 0.78 (0.49,1.24) |

0.288 | 0.94 (0.84,1.06) |

0.292 |

| Selim Total (range: 0-36) | 0.97 (0.96,0.98) |

<0.001 | 1.09 (1.08,1.09) |

<0.001 | 0.94 (0.91,0.97) |

0.001 | 1.20 (0.93,1.56) |

0.169 | 1.46 (1.15,1.86) |

0.002 | 1.13 (1.04,1.23) |

0.003 |

Each year (FY02-FY07) in the model denotes patients' study entry, where FY08 was used as reference. FY09 was not included as the outcome of one-year polypharmacy could not be assessed. VA data prior to FY05 was not available.

Multivariable Models of One-year Admission to Hospital across Systems

We also examined multivariable logistic regression models of one-year admission to hospital in VA and HMORN samples. The model was not conducted on the NAMCS sample due to its lack of follow-up information. Increased antipsychotic polypharmacy was significantly associated with increased odds of one-year admission in all models, with odds ratio 1.41 to 2.44 (OR=1.87, 95% CI: 1.77-1.97 VA tapered; OR=2.44, 95% CI: 2.34-2.54 VA one-year; OR=1.41, 95% CI: 1.33-1.51 VA one-week; OR=2.22, 95% CI: 1.25-2.95 HMORN site 1; OR=1.57, 95% CI: 1.18-2.08 HMORN site 2).

Discussion

This study compared antipsychotic medication use and polypharmacy for patients diagnosed with schizophrenia (or a non-specific psychotic disorder) across healthcare systems, including a national federal system (VA), a national non-federal healthcare setting (NAMCS), and two non-federal healthcare systems (HMORN). As a result of the completeness of VA data, several methods of analyses were compared when assessing antipsychotic polypharmacy among patients with schizophrenia. Our examination of the unadjusted longitudinal trends, both in the VA system and among non-federal US clinics, suggests tremendous variation in the use of antipsychotics for these patients. In particular, we did not see evidence of ongoing increases in antipsychotic polypharmacy.

Rates of antipsychotic use across the nationwide NAMCS outpatient clinics and VA system were similar and greater than the rates found within the HMORN healthcare systems. However, it is concerning that higher rates of antipsychotic use were not observed when a constant medication regimen is the recommended practice to manage schizophrenia. The lower rates could reflect patients who fill their prescriptions outside of the studied systems, which may be less common in the VA due to patients' greater service-connected disability and lower copayments. NAMCS provided the only data where patients were not necessarily covered by some form of health insurance (16% or less). As a result, these patients may incur increased prescription costs and restrict their use of antipsychotics due to financial burden. Medicaid policies may impose limits on polypharmacy. These data suggest that different treatment settings exhibit different prescribing patterns, perhaps partly influenced by formulary decisions or copayment policies. The latter point is well documented concerning its impact on cost-related problems obtaining refills for patients with schizophrenia.42,43 This finding was consistent with those reported in several VA studies,30,31,44 in which national VA samples were more likely to receive antipsychotic medications, while the opposite was observed in VA outpatients from two states. Yet low treatment rates were observed among the patients accessing care in integrated care-and-coverage systems.

Antipsychotic polypharmacy prevalence and trends among patients varied between the different healthcare systems, with generally higher and more stable rates observed among the whole sample of VA patients. However, other methods of analysis using VA data revealed lower rates. Several potential explanations for the higher rates of polypharmacy in VA can be offered: (1) VA patients have more comprehensive medication coverage, and therefore the system might better afford multiple drugs. Here, cost would be less of a barrier to seek prescription fills, 45,46 although copays can still be a major deterrent for VA patients with schizophrenia.43 (2) More stabilized rates are likely due to the fact that federal systems, including VA, are typically less subjective to funding fluctuations, and thus, able to provide consistent care to its patients. This consistently includes nationwide medical record access when patients move from one VA to another. (3) Selim and Charlson scores reflecting physical and mental health comorbidities were higher in VA patients with schizophrenia than other systems. That is, more complicated clinical presentations may affect prescribing decisions, including antipsychotic polypharmacy, to help patients achieve symptomatic relief. (4) VA users are less likely to drop out of care since the psychiatric sector has the lowest likelihood of mental health treatment dropout compared with the general medical care.47 (5) VA data may have been more complete leading to an apparent difference that might be an artifact of the data available.

In addition, non-VA patients usually do not have uniform coverage and benefit levels,48 so the fluctuation in polypharmacy rates for non-federal patients may reflect policy or coverage changes. Within the civilian systems, lower rates of any antipsychotic use were observed for the HMORN sites compared to NAMCS, however, relatively similar rates of polypharmacy were observed across these systems. These patients differ from NAMCS patients in that all have healthcare coverage.

It is noteworthy that VA patients were distinctly older and more likely to be male, reflective of the composition of military personnel and a predominantly Vietnam era schizophrenia cohort. However, this profile is evolving as younger Veterans from the ongoing Global Wars on Terrorism enter the system, along with a much higher presence of women in the military. VA patients also appeared to have more comorbidities than the non-federal systems under study, indicating an overall sicker population.49 This is consistent with VA's focus on catering to the least advantaged veterans. However, when implementing the one-week method of analysis to simulate data obtained from the NAMCS, the smaller sample of VA patients appeared to have similar rates of comorbidity to both NAMCS and HMORN. This study's findings suggest that the quality of the data and the method used to examine polypharmacy dramatically affect results obtained.50 Still, all sources with follow-up data confirmed a positive correlation between polypharmacy and hospital admission. For some, antipsychotic polypharmacy may lead to adverse events. Alternatively, we recognize that the most difficult to treat patients could be receiving polypharmacy, and concomitantly, be the patients most likely to be admitted due to their illness severity regardless of polypharmacy. Polypharmacy may identify patients who are not stabilized on antipsychotic medication, or refractory to multiple antipsychotics, or covertly non-adherent.

Notably, a few effective interventions have been developed to curb the problem of overprescribing antipsychotics,51 including educational approaches for patients and clinicians. Generally, assertive interventions appear to be more effective in reducing antipsychotic polypharmacy than passive interventions. While there is insufficient evidence to support the utility of many forms of polypharmacy, specific sequences and combinations of antipsychotics may be beneficial for some patients. Certainly additional research is warranted to develop interventions that address the problem of excessive prescription medication burden while teasing out appropriate polypharmacy. Data from the current study suggest that interventions may need to be adapted for different healthcare systems with varying patient risks for polypharmacy. To empirically inform practice guidelines, research is also needed to more intensively explore the impact of growing polypharmacy practices on health outcomes and their personal and systemic costs. Electronic systems to signal polypharmacy could assist in identifying patients requiring more complex treatment and those who are at risk for adverse events, ultimately leading to improved clinical practice and fiscal well-being.

Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. First, NAMCS relies upon office visit level survey data while the other samples utilized patient level data extracted from medical records, which could have contributed to differences in observed polypharmacy rates. Second, the samples had limited comparability in terms of patient demographics, although we also view the diversity across healthcare system types as a notable strength, providing confirmation of the overall trends in polypharmacy while highlighting the degree of variation. Third, we did not have the ability to investigate other important factors or associated outcomes such as previous treatments, patient side-effect profiles, uncommon psychiatric conditions not captured by Selim, severity of illness, mortality rates, or other factors related to treatment decisions, cost of treatment, provider behavior, pharmacy formulary policies changing over time, or medication copayment policies. Fourth, data were only available for VA patients in the years 2005-2009 due to IRB approval (see Figure 2 for patient flow). Fifth, lack of follow-up information in NAMCS doesn't allow us to model temporally subsequent outcomes in this sample. Sixth, due to the small samples from two HMORN sites, we only assessed these two samples yearly from FY02-FY09 rather than use one-week look back periods. Finally, prescribing pharmacy data of VA and self-reported medication data without fill information of NAMCS may not truly reflect actual antipsychotic use of the patients.52,53 Whether patients were adherent to their fills was also a limitation. However, despite these limitations, this study presented a rare comparison of the use of antipsychotics for patients with schizophrenia or psychotic disorders in four healthcare settings with at least two national samples using recent data (FY02-FY09).

Figure 2. Study Design Flow Chart.

Conclusion

Despite the PORT guidelines' recommendation of antipsychotic monotherapy, nearly one-fifth of patients with schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders in most of the healthcare systems were prescribed antipsychotic polypharmacy. Recognizing that the treatment of an individual patient can be more complex than accounted for in initial guidelines, and that qualitative factors concerning multiple antipsychotics should be evaluated, antipsychotic polypharmacy represents a system-wide problem to be continually monitored as such practices were found to be associated with hospital admission.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures: This work was supported by the Center for Applied Health Research, a research center jointly sponsored by Central Texas Veterans Health Care System and Scott & White Healthcare in Temple, TX, and by grants from Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development #IIR-09-335 (PI: Laurel A. Copeland). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

The authors declare no financial or other conflicts of interests.

Contributor Information

FangFang Sun, Center for Applied Health Research, jointly sponsored by Central Texas Veterans Health Care System and Scott & White Healthcare, Temple, TX.

Eileen M. Stock, Center for Applied Health Research, jointly sponsored by Central Texas Veterans Health Care System and Scott & White Healthcare, Temple, TX; Texas A&M Health Sciences Center, College of Medicine, Bryan, TX.

Laurel A. Copeland, Central Texas Veterans Health Care System, Temple, TX; Center for Applied Health Research, jointly sponsored by Central Texas Veterans Health Care System and Scott & White Healthcare, Temple, TX; Texas A&M Health Sciences Center, College of Medicine, Bryan, TX.

John E. Zeber, Health Outcomes Core, jointly sponsored by Central Texas Veterans Health Care System and Scott & White Healthcare, Temple, TX; Texas A&M Health Sciences Center, College of Medicine, Bryan, TX.

Brian K. Ahmedani, Center for Health Policy & Health Services Research at Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, MI.

Sandra B. Morissette, VA VISN 17 Center of Excellence for Research on Returning War Veterans, Waco, TX; Texas A&M Health Sciences Center, College of Medicine, Bryan, TX.

References

- 1.Mikell CB, McKhann GM, Segal S, McGovern RA, Wallenstein MB, Moore H. The hippocampus and nucleus accumbens as potential therapeutic targets for neurosurgical intervention in schizophrenia. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2009;87(4):256–265. doi: 10.1159/000225979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'carroll R. Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2000;6:161–168. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faries D, Ascher-Svanum H, Zhu B, Correll C, Kane J. Antipsychotic monotherapy and polypharmacy in the naturalistic treatment of schizophrenia with atypical antipsychotics. BMC Psychiatry. 2005;5:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-5-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kreyenbuhl J, Buchanan RW, Dickerson FB, Dixon LB. The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2009. Schizophr Bull. 2010 Jan;36(1):94–103. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehman AF, Kreyenbuhl J, Buchanan RW, et al. The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2003. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(2):193–217. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM. Translating research into practice: the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24(1):1–10. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young AS, Sullivan G, Duan N. Patient, provider, and treatment factors associated with poor-quality care for schizophrenia. Ment Health Serv Res. 1999 Dec;1(4):201–211. doi: 10.1023/a:1022369323451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, et al. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010 Jan;36(1):71–93. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004 Feb;161(2 Suppl):1–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller AL, Crismon ML, Rush AJ, et al. The Texas medication algorithm project: clinical results for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(3):627–647. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore TA, Buchanan RW, Buckley PF, et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project antipsychotic algorithm for schizophrenia: 2006 update. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007 Nov;68(11):1751–1762. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Guidance on the use of newer (atypical) antipsychotic drugs for the treatment of schizophrenia. Technology Appraisal Guidance London. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 13.The expert consensus guideline series. Treatment of schizophrenia 1999. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(Suppl 11):3–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel MX, Haddad PM, Chaudhry IB, McLoughlin S, Husain N, David AS. Psychiatrists' use, knowledge and attitudes to first- and second-generation antipsychotic long-acting injections: comparisons over 5 years. J Psychopharmacol. 2010 Oct;24(10):1473–1482. doi: 10.1177/0269881109104882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Attard A, Taylor DM. Comparative effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenia: what have real-world trials taught us? CNS Drugs. 2012 Jun 1;26(6):491–508. doi: 10.2165/11632020-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganguly R, Kotzan JA, Miller LS, Kennedy K, Martin BC. Prevalence, trends, and factors associated with antipsychotic polypharmacy among Medicaid-eligible schizophrenia patients, 1998-2000. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004 Oct;65(10):1377–1388. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams EO, Stock EM, Copeland LA, et al. Payer Types Associated with Antipsychotic Polypharmacy in an Ambulatory Care Setting. Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Services Research. 2012 Sep;3(3):149–155. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goren JL, Parks JJ, Ghinassi FA, et al. When is antipsychotic polypharmacy supported by research evidence? Implications for QI. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008 Oct;34(10):571–582. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kreyenbuhl J, Valenstein M, McCarthy JF, Ganoczy D, Blow FC. Long-term combination antipsychotic treatment in VA patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006 May;84(1):90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Covell NH, Jackson CT, Evans AC, Essock SM. Antipsychotic prescribing practices in Connecticut's public mental health system: rates of changing medications and prescribing styles. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28(1):17–29. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goh YL, Seng KH, Chuan AS, Chua HC. Reducing antipsychotic polypharmacy among psychogeriatric and adult patients with chronic schizophrenia. Perm J Spring. 2011;15(2):52–56. doi: 10.7812/tpp/11-017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiang YT, Wang CY, Si TM, et al. Antipsychotic polypharmacy in inpatients with schizophrenia in Asia (2001-2009) Pharmacopsychiatry. 2012 Jan;45(1):7–12. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1286345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dolder CR, McKinsey J. Antipsychotic polypharmacy among patients admitted to a geriatric psychiatry unit. J Psychiatr Pract. 2011 Sep;17(5):368–374. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000405368.20538.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loosbrock DL, Zhao Z, Johnstone BM, Morris LS. Antipsychotic medication use patterns and associated costs of care for individuals with schizophrenia. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2003 Jun;6(2):67–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller AL, Craig CS. Combination antipsychotics: pros, cons, and questions. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28(1):105–109. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu B, Ascher-Svanum H, Faries DE, Correll CU, Kane JM. Cost of antipsychotic polypharmacy in the treatment of schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiivet RA, Llerena A, Dahl ML, et al. Patterns of drug treatment of schizophrenic patients in Estonia, Spain and Sweden. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1995 Nov;40(5):467–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1995.tb05791.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sim K, Su A, Fujii S, et al. Antipsychotic polypharmacy in patients with schizophrenia: a multicentre comparative study in East Asia. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004 Aug;58(2):178–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02102.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheppard C, Beyel V, Fracchia J, Merlis S. Polypharmacy in psychiatry: a multi-state comparison of psychotropic drug combinations. Dis Nerv Syst. 1974 Apr;35(4):183–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leslie DL, Rosenheck RA. Benchmarking the quality of schizophrenia pharmacotherapy: a comparison of the Department of Veterans Affairs and the private sector. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2003 Sep;6(3):113–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenheck RA, Desai R, Steinwachs D, Lehman A. Benchmarking treatment of schizophrenia: a comparison of service delivery by the national government and by state and local providers. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000 Apr;188(4):209–216. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200004000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen CI, Cohen GD, Blank K, et al. Schizophrenia and older adults. An overview: directions for research and policy. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry Winter. 2000;8(1):19–28. doi: 10.1097/00019442-200002000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang PS, Schneeweiss S, Avorn J, et al. Risk of death in elderly users of conventional vs. atypical antipsychotic medications. N Engl J Med. 2005 Dec 1;353(22):2335–2341. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Statistics NCfH. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey 2008. [Accessed February 6, 2008]; ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NAMCS/

- 35.Go AS, Magid DJ, Wells B, et al. The Cardiovascular Research Network: a new paradigm for cardiovascular quality and outcomes research. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2008 Nov;1(2):138–147. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.801654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stevens AB, Sanghi S. Emerging frontiers in healthcare research and delivery.: the 16th Annual HMO Research Network Conference, March 21-24, 2010, Austin, Texas. Clin Med Res. 2010 Dec;8(3-4):176–178. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2010.974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Copeland L, Sun F, Haller I, et al. PS3-47: Rural Health Research Initiative in the HMORN: A New Scientific Interest Group. Clin Med Res. 2013 Sep;11(3):142. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Selim AJ, Fincke G, Ren XS, et al. Comorbidity assessments based on patient report: results from the Veterans Health Study. J Ambul Care Manage. 2004 Jul-Sep;27(3):281–295. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200407000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Copeland LA, Zeber JE, Wang CP, et al. Patterns of primary care and mortality among patients with schizophrenia or diabetes: a cluster analysis approach to the retrospective study of healthcare utilization. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:127. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hing E, Cherry DK, Woodwell DA. National ambulatory medical care survey: 2003 summary. Advance data from vital and health statistics. 2005;(365) Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad365.pdf. [PubMed]

- 42.Soumerai S. Unintended outcomes of medicaid drug cost-containment policies on the chronically mentally ill. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(Suppl 17):19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zeber JE, Grazier KL, Valenstein M, Blow FC, Lantz PM. Effect of a medication copayment increase in veterans with schizophrenia. Am J Manag Care. 2007 Jun;13(6 Pt 2):335–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shekelle PG, Asch S, Glassman P, Matula S, Trivedi A, Miake-Lye I. Comparison of Quality of Care in VA and Non-VA Settings: A Systematic Review. Washington (DC): 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Piette JD, Heisler M. Problems due to medication costs among VA and non-VA patients with chronic illnesses. Am J Manag Care. 2004 Nov;10(11 Pt 2):861–868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piette JD, Wagner TH, Potter MB, Schillinger D. Health insurance status, cost-related medication underuse, and outcomes among diabetes patients in three systems of care. Med Care. 2004 Feb;42(2):102–109. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000108742.26446.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olfson M, Mojtabai R, Sampson NA, et al. Dropout from outpatient mental health care in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009 Jul;60(7):898–907. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.7.898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watkins KE, Smith B, Paddock SM, et al. Program Evaluation of VHA Mental Health Services: Capstone Report. 2011 http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2011/RAND_TR956.pdf.

- 49.Morgan RO, Teal CR, Reddy SG, Ford ME, Ashton CM. Measurement in Veterans Affairs Health Services Research: veterans as a special population. Health Serv Res. 2005 Oct;40(5 Pt 2):1573–1583. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00448.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stock EM, Copeland LA, Tsan JY, Zeber JE, Cooper TL. Method of Analysis as a Factor in Models of Admission among Veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan Deployments. 2012 In Review. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tani H, Uchida H, Suzuki T, Fujii Y, Mimura M. Interventions to reduce antipsychotic polypharmacy: A systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2012 Nov 14; doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cramer JA, Rosenheck R. Compliance with medication regimens for mental and physical disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 1998 Feb;49(2):196–201. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Dolder CR, Leckband SG, Jeste DV. Prevalence of and risk factors for medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia: a comprehensive review of recent literature. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002 Oct;63(10):892–909. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]