Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To investigate miR-155 in the SOD1 mouse model and human sporadic and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

METHODS

Nanostring microRNA, microglia and immune gene profiles, protein mass spectrometry and RNA-seq analyses were measured in spinal cord microglia, splenic monocytes and spinal cord tissue from SOD1 mice and in spinal cord tissue of familial and sporadic ALS. miR-155 was targeted by genetic ablation or by peripheral or centrally administered anti-miR-155 inhibitor in SOD1 mice.

RESULTS

In SOD1 mice we found loss of the molecular signature that characterizes microglia and increased expression of miR-155. There was loss of the microglial molecules P2ry12, Tmem119, Olfml3, transcription factors Egr1, Atf3, Jun, Fos, Mafb and the upstream regulators Csf1r, Tgfb1 and Tgfbr1 which are essential for microglial survival. Microglia biological functions were suppressed including phagocytosis. Genetic ablation of miR-155 increased survival in SOD1 mice by 51d in females and 27d in males and restored the abnormal microglia and monocyte molecular signatures. Disease severity in SOD1 males was associated with early upregulation of inflammatory genes including Apoe in microglia. Treatment of adult microglia with APOE suppressed the M0-unique microglia signature and induced a M1-like phenotype. miR-155 expression was increased in the spinal cord of both familial and sporadic ALS. Dysregulated proteins that we identified in human ALS spinal cord were restored in SOD1G93A/miR-155−/− mice. Intraventricular anti-miR-155 treatment derepressed microglial miR-155 targeted genes and peripheral anti-miR-155 treatment prolonged survival.

INERPRETATION

We found overexpression of miR-155 in the SOD1 mouse and in both sporadic and familial human ALS. Targeting miR-155 in SOD1 mice restores dysfunctional microglia and ameliorates disease. These findings identify miR-155 as a therapeutic target for the treatment of ALS.

INTRODUCTION

There is evidence that the immune system plays a role in ALS, though these mechanisms are not well understood.1 Although ALS is not primarily considered an inflammatory or immune mediated disease, immune mechanisms appear to play a role in pathogenesis of the disease. In both ALS patients and animal models, inflammatory responses are observed.1–10 Furthermore, non-neuronal cells such as microglia11 and astrocytes12 are activated during disease progression and evidence suggests that they contribute to neuronal death.12 It has been reported that microglia adopt an pro-inflammatory (M1) phenotype in SOD1 mice13 and are neurotoxic.14, 15 In addition, selective ablation of mutant SOD1 in astrocytes and microglial cells by conditional deletion11 and neonatal wild type bone marrow transplantation5 increased motor neuron survival and lifespan. Deletion of galectin-3, which is induced in an anti-inflammatory (M2) microglia phenotype,16 exacerbates microglial activation and accelerates disease progression in a SOD1 mouse model.17

We previously reported that there is recruitment of Ly6CHi peripheral inflammatory monocytes to the spinal cord of SOD1G93A mice and that anti-Ly6C-mediated modulation of Ly6C monocytes reduced their recruitment to the spinal cord, diminished neuronal loss and extended survival.8 Furthermore, we found a unique microRNA signature in Ly6CHi monocytes both in SOD1 mice and in CD14+/CD16− monocytes from ALS patients and in spinal cord microglia of SOD1 mice. These experiments led to the discovery of miR-155 as being one of the major affected biological pathways in the animal model and in human ALS.8 Thus, we found that miR-155 was highly upregulated in the spinal cord-derived CD39+ resident microglia in SOD1 mice and to some extent in peripheral and recruited monocytes.8

miR-155 plays an important role in inflammatory responses. miR-155 promotes tissue inflammation by enhancing the generation of Th17 cells,18 is highly upregulated during macrophage inflammatory responses19–22 and is upregulated in multiple sclerosis lesions.23, 24 Furthermore, miR-155 has been implicated in increasing pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion by targeting SOCS1 mRNA.25 We and others have shown that targeting of miR-155 either by genetic manipulation or by using a miR-155 inhibitor attenuates disease in the EAE model of multiple sclerosis.18, 26 Of note, miR-155 deficient animals are phenotypically normal and breed well, despite dysregulation of cells in the immune compartment.27, 28

Based on our findings of a pro-inflammatory signature in both peripheral monocytes and microglia in ALS and the known role of miR-155 in inflammation, we investigated the role of miR-155 in ALS by creating SOD1 mice that were deficient for miR-155 and by treating animals at the onset of disease with anti-miR-155 given either peripherally or into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). We hypothesized that if the inflammatory features of monocytes and microglial cells played an important role in the SOD1 model of ALS, attenuation or downregulation of these pro-inflammatory processes by miR-155 ablation would attenuate the disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

B6/SJL-SOD1G93A Tg, SOD1-wild type (WT), and non-Tg mice were provided by Prize4Life or purchased from the Jackson Laboratories. miR-155−/− B6.Cg-Tg males and females were obtained from Jaxmice laboratories. SOD1G93A on a B6 congenic background obtained from Jaxmice laboratories were bred with non-Tg C57Bl/6 miR-155−/− mice. Non-transgenic miR-155−/− were then backcrossed to F1-SOD1G93A/miR-155−/+ to produce F2-SOD1G93A/miR-155−/− and SOD1G93A/miR-155+/− mice which had a deletion of one or two miR-155 alleles. qPCR analysis showed a high copy number of mSOD1 in all F2 progeny compared to the original breeders (SOD1G93A/miR-155+/+). Control low-copy SOD1 being used as a control for qPCR analysis mice were purchased from JaxMice. We also measured the copy number of SOD1 protein by quantitative mass spectrometry analysis and found no difference between F2-SOD1G93A/miR-155−/− and SOD1G93A/miR-155+/− mice (see Fig 9B and Supplementary Table 11). All mice were housed with sterile food and water ad libitum. All animals were housed in temperature and humidity controlled rooms, maintained on a 12h/12h light/dark cycle (lights on at 7:00) and age- and gender-matched in each experiment. All strains were kept in identical housing conditions. Animals were euthanized through CO2 inhalation. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Harvard Medical School approved all experimental procedures involving animals.

Figure 9. Genetic ablation of miR-155 reverses impaired microglia phagocytic function in SOD1 mice.

(A) Representative confocal micrographs of phagocytosing microglia isolated from spinal cord of WT/miR-155+/−, WT/miR-155−/−, SOD1/miR-155+/− and SOD1/miR-155−/− female mice at 120 days of age. Microglia were incubated for 2 hours with fluorescently-labeled UV-irradiated neurons and stained with anti-IBA1 antibody. (B) Orthogonal projections of confocal z-stacks shows intracellular engulfed dead neuron in microglia. (C) Bar graphs comparing engulfed UV-irradiated neurons per microglia cell (mean ± s.e.m) (ns, non-significant; ****, P < 0.0001; one-way ANOVA; Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons test). Counts preformed from 70 cells in each group from biological duplicates.

Clinical evaluation of SOD1 mice

Animals were assessed clinically by neurobehavioral testing (rotarod performance and neurologic score) and survival of experimental groups of SOD1 mice with different expression levels of miR-155 in females and males as described previously.8

Spinal cord microglia isolation and sorting

Mice were transcardially perfused with ice-cold phosphate-buffer saline (PBS) and their spinal cords were dissected. Tissue was homogenized using a Teflon-stick homogenizer. Single cell suspensions were prepared and centrifuged over a 37%/70% discontinuous Percoll gradient (GE Healthcare), mononuclear cells isolated from the interface, and total cell count determined. Isolated cells were labeled with combination of FRCLS and CD11b antibodies to specifically sort resident microglia followed by total RNA isolation and gene/miRNA expression profiling. Cell sorting was performed using a Becton Dickinson FACSARIA cell sorter.

Flow Cytometry

For fluorescent-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis, mice were transcardially perfused with 50ml 0.01 M PBS and their spinal cords were homogenized using a Teflon-stick homogenizer. Mononuclear cells were separated through Percoll (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) gradient centrifugation. Cells were pre-blocked with anti-CD16/CD32 (clone 2.4G2, BD Biosciences, 5 μg ml−1), and stained on ice for 30 min with combinations of CD11b-PE-Cy™7 (clone N418, eBioscience, 5 μg ml−1) and FCRLS (clone 4G11, 5 μg ml−1)29 conjugated to APC (Biolegend). Appropriate antibody IgG isotype controls (BD Biosciences) were used for all staining. FACS analysis was performed on a LSR machine (BD Biosciences), and data analyzed with FlowJo Software (TreeStar).

Primary adult mouse microglia culture

We used our previous described protocol to culture directly isolated adult microglia from CNS ex vivo.29 In brief, resident microglia were isolated from spinal cords of non-transgenic miR-155+/−, non-transgenic miR-155−/−, SOD1G93A/miR-155−/+ and SOD1G93A/miR-155−/− mice at age of 120 days. Mononuclear cells were separated through Percoll (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) 37%/70% gradient centrifugation (1200 rpm, room temperature, with minimal acceleration and no brake using a swinging bucket rotor). Mononuclear cells were isolated from the interface. Cells were stained on ice for 20 min with anti-FCRLS mAb at 1:200 dilution in blocking buffer containing 0.25% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich) in HBSS (Invitrogen). Cell sorting was performed using Becton Dickinson FACSARIA cell sorter. Sorted microglia were cultured in 12-well plate (6.5×104 cells/well in 2 ml) in poly-D-lysine coated plates (BD Biosciences), and grown in microglia culture medium (DMEM/F-12 Glutamax; Invitrogen; supplemented with 10% FCS, 100U ml−1 penicillin, 100 mg ml−1 streptomycin and mouse recombinant carrier free MCSF 10ng/ml (R&D Systems) and 50ng/ml human recombinant TGFβ1 (Miltenyi Biotec) for 5 days at 37°C, 5% CO2. Cells were cultured for at least 5 days without changing media before phagocytosis assay.

Isolation of hippocampal neurons

Primary hippocampal neurons were used for phagocytosis assay described below. The cells were prepared from embryos at age E18.5. Cerebral cortices and hippocampi were isolated and freed from meninges. Tissues were first digested with 0.25% trypsin in Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) for 15 min at 37°C, then washed three times with HBSS and triturated with fire-polished glass pipettes until single cells were obtained. Cell suspension was then filtered through a 70 and a 40 μm cell strainer and subjected to a spin at 1000g for a few minutes. Supernatant was removed and cell pellet was resuspended with 10 ml of HBSS. Cell density was then determined with a hemocytometer and cells were seeded at different densities according to the experimental design and need. We used Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s media (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS for the initial plating, and the medium was changed to Neurobasal supplemented with 1× B27 (Invitrogen) in 3 h. Half medium was changed every 3 days.

Microglia phagocytosis assay

To determine the phagocytic ability of microglial cells we have adopted previous protocol30 with slight modification. In brief, hippocampal neurons, as described above, were treated with ultraviolet light for 153min. The cells were stained 6h post-exposure to UV with 5(6)-TAMRA, succinimidyl ester (Invitrogen), and washed thoroughly with cold PBS before they were used for incubation with cell culture and fed on to adult microglia isolated from non-transgenic miR-155-+/−, non-transgenic miR-155−/−, SOD1G93A/miR-155−/+ and SOD1G93A/miR-155−/− mice at age of 120 days, as described above. Microglia cells (1 × 104) were cultured in 8-well Nunc™ Lab-Tek™ II Chamber Slide™ System (Thermo Scientific). After 2 hours at 373°C and 5% CO2, cells were washed and fixed with 2.5% PFA for 20 min in room temperature. Slides were blocked in 0.05% Triton X-100, 0.1% Tween 20, and 2% horse serum, followed by incubation with rabbit anti-Iba1 (1:500; Wako, cat. no. 019-19741) for 1h at room temperature. Slides were then washed for 53min three times at room temperature in 0.05% Tween-20 (Sigma) in PBS, followed by incubation with Alexa-fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc.) for 13h at room temperature. Coverslips were washed again with 0.05% Tween-20 (Sigma) in PBS (53min, three times) and mounted with polyvinyl alcohol with diazabicylo-octane anti-fading agent or ProLong® Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen). Slides were analyzed using confocal microscopy and ImageJ software. Quantitative analysis of engulfed UV-irradiated neurons per microglia cell was performed in a blind manner.

LNA-anti-miR-155 treatment

We used LNA-anti-miR-155 (5′-TcAcAATtaGmCAtTA-3′) and scrambled LNA-anti-miR-155 (5′-TcAam CATt aGAmCtTA-3′) both purchased from Exiqon. We used liposome complexes of the oligonucleotides and Invivofectamine31 for treatment with anti-miR-155. Three injections were given peripherally (ip) every second day. For CNS treatment, we administered 2mg/kg of anti-miR-155 at disease onset as defined by body weight loss of 5% of the mouse maximal weight (approximately 90 days of age) with one injection given stereotaxically into the lateral cerebral ventricle using the following coordinates: anteroposterior, −0.4 mm; mediolateral, 1 mm; dorsoventral, −2.3 mm relative to bregma, with the help of a pump-driven Hamilton microsyringe fitted with a 33-gauge stainless-steel needle.

RNA isolation

Total RNA was extracted using mirVanaTM miRNA isolation kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA (20–40ng) was used in 20–40μl of reverse transcription reaction (high-capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit; Applied Biosystems) and 3ng RNA in 5μL reverse transcription reaction with specific miRNA probes (Applied Biosystems). qPCR reactions were performed in duplicates or triplicates. mRNA or miRNAs levels were normalized relative to GAPDH or U6, respectively, by the formula 2^(−ΔCt), where ΔCt = CtmiR-X-CtU6 or GAPDH. All data are mean of duplicates, and the standard errors of mean were calculated between duplicates or triplicates. Real time PCR reaction was performed using Vii7 (Applied Biosystems). All qRT-PCRs were performed in duplicate or triplicate, and the data are presented as mean ± standard error of mean (s.e.m).

Human spinal cord specimens

Post mortem spinal cord specimens were obtained from Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) pathology department at the time of autopsy from 8 patients with sporadic ALS (sALS), 2 patients with familial ALS (fALS), and 10 control subjects. Both fALS patient carried the SOD1 A4V mutation. One was a 54-year-old male with disease duration of 77 months and a post mortem interval of 24 hours. The second was a 51-year-old female with disease duration of 13 months and a post mortem interval of 12 hours. All ALS patients were at least 18 years old and met El Escorial Criteria for possible, probable, or definite ALS. Of the 10 ALS subjects, 9 subjects had limb symptom onset and 1 subject’s symptom onset location was unknown. Of the 10 control subjects, all were clinically neurologically normal at the time of death (see Table 2). Neuropathological examination confirmed the clinical diagnosis for all ALS subjects. Spinal cord samples from ALS subjects were received from the Massachusetts Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) via the Neurological Clinical Research Institute (NCRI) at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) under approved research protocols. Samples from control subjects were received from Department of Neuropathology at Massachusetts General Hospital. Specimens were taken from the lumbar region of each spinal cord; however, the region of one HC cord sample (HC A12-200) was unspecified. Samples were stored at −80°C until used. All post mortem samples were obtained and used in accordance with the policies of in the institutional review boards at Massachusetts General and Brigham and Women’s Hospitals. Tissues were used for immunohistochemical and profile analysis.

Table 2.

CSF samples - Demographic and clinical features of study participants.

| Characteristic | Disease Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| sALS | fALS | Healthy | |

| Number of patients | 10 | 4 | 10 |

|

| |||

| Disease duration (months) +/− SD | 22.9 +/−15.3 | 9.3 +/− 5.2 | n/a |

|

| |||

| Age in Years +/− SD | 57.8 +/− 17.2 | 37.1 +/− 13.3 | 53.3 +/− 16.1 |

|

| |||

| Percent Male | 80% | 75% | |

|

| |||

| Site of Disease Onset | |||

| Bulbar | 10% | 0% | n/a |

| Cervical | 20% | 0% | n/a |

| Lumbar | 20% | 50% | n/a |

| Unknown | 50% | 50% | n/a |

Cerebrospinal fluid samples

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was collected from patients recruited from the MGH multidisciplinary ALS Clinic and NCRI. The MGH institutional review board approved the study and all subjects underwent informed consent procedure prior to being enrolled in the study. ALS patients were at least 18 years old and met El Escorial Criteria for the diagnosis of ALS. Study volunteers providing CSF were enrolled over the period from 09/05/1997 to 03/15/2011. For all participants, demographic information was collected at the time of biofluid collection. For patients with ALS, disease information in the form of disease duration and region of disease onset were also collected. CSF samples were collected from 10 patients with sporadic ALS, 4 patients with familial ALS who carried the SOD1 mutation, and 10 volunteers without a history of neurologic disease or relatives with ALS (see Table 3). One patient with sporadic ALS had upper motor neuron predominant symptoms. CSF was obtained via lumbar puncture performed by an experienced neurologist and collected into polystyrene tubes prior to processing. Within 30 minutes of collection, CSF samples were centrifuged at approximately 1780 RCF for 10 min. The supernatant was immediately aliquoted into 0.5ml polypropylene cryovials with screw tops for storage at −80C. The use of rigorous standard operating procedures ensured high quality and uniform samples.

TABLE 3. Dysregulated biological functions in spinal cord microglia from SOD1G93A mice.

Early and late downregulated and upregulated cluster genes datasets (see Supplementary Table 1) were uploaded separately and used for comparison in IPA functional analysis.

| Functions Annotation | p-Value | Activation z-score |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

|

Early Downregulated (60 days of age) genes

| ||

| Maturation of phagocytes | 2.10E-11 | −2.055 |

| Cell cycle progression | 6.65E-06 | −2.091 |

| Binding of cells | 2.77E-05 | −2.491 |

| Proliferation of cells | 3.23E-05 | −3.647 |

| Transactivation of RNA | 1.48E-04 | −3.085 |

| Aggregation of blood cells | 3.73E-04 | −2.211 |

| Weight loss | 6.26E-04 | 2.393 |

| Stimulation of leukocytes | 7.46E-04 | −2.181 |

| Synthesis of prostaglandin | 8.30E-04 | −2.184 |

| Synthesis of DNA | 9.32E-04 | −2.09 |

|

| ||

|

Late Downregulated (End-stage) genes

| ||

| Cell movement of phagocytes | 1.61E-07 | −2.661 |

| Recruitment of blood cells | 1.19E-06 | −2.041 |

| Mortality | 1.01E-05 | 2.433 |

| Adhesion of blood cells | 1.71E-05 | −2.2 |

| Cellular homeostasis | 6.54E-05 | −3.162 |

| Necrosis | 1.86E-04 | −2.422 |

| Activation of leukocytes | 1.90E-04 | −2.006 |

| Release of Ca2+ | 2.07E-04 | −2 |

| Protein kinase cascade | 3.35E-04 | −2.19 |

| Phagocytosis of cells | 8.66E-04 | −2.453 |

| Phosphorylation of protein | 5.10E-04 | −2.387 |

| Fatty acid metabolism | 1.03E-03 | −2.54 |

| Binding of antigen presenting cells | 1.15E-03 | −2 |

| Cell death of macrophages | 1.92E-03 | −2.219 |

| Ion homeostasis of cells | 2.34E-03 | −2.768 |

|

| ||

|

Upregulated (End-stage) genes

| ||

| Chemotaxis of macrophages | 2.14E-10 | 2.2 |

| Migration of antigen presenting cells | 3.72E-07 | 2.178 |

| Degeneration of cells | 5.27E-06 | −2.137 |

| Quantity of myeloid cells | 1.93E-05 | 2.195 |

Immunohistochemistry

Transverse cryosections of the spinal cord (30 μm) were treated with a permeabilization/blocking solution containing 10% FCS, 2% bovine serum albumin, 1% glycine, and 0.05% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 hour. Primary antibodies rabbit anti-P2ry12 pAb (1:200, validated in ref.29), mouse anti-NeuN (1:500; Millipore) and rabbit anti-Iba1 (1:500; Wako) were diluted in blocking solution in PBS containing 0.05% Triton X-100 and 10 % horse serum and 2% BSA. Human spinal cord ventral horn sections (30 μm) were treated the permeabilization/blocking solution and stained with goat anti-APOE pAb (1:2000, Millipore). Sections were incubated with the primary antibody for 12 hours at 4°C, washed for 53min three times at room temperature in 0.05% Tween-20 (Sigma) in PBS and incubated with the secondary antibodies in blocking solution for 1 hour at room temperature while protected from light. Secondary antibodies used for immunohistochemistry were donkey anti-rat Cy3 and donkey anti-mouse FITC, donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor® 647 at a dilution of 1:500. Sections were then washed for 53min three times at room temperature in 0.05% Tween-20 (Sigma) in PBS and coverslipped in ProLong® Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen). Secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc and Abcam. Control sections (not treated with primary antibody) were used to distinguish specific from nonspecific staining or autofluorescent components. For DAB (Diaminobenzidine substrate) staining (Fig 6A), endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked in methanol with 0.02 % hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) for 30 min. Prior to staining with P2ry12 (1:750), Iba1 (1:1000) and iNOS (rabbit anti NOS II, AB 16311; EMD Milipore Corporation, Temecula CA, USA), non-specific antibody binding was blocked by incubating the sections with 10 % fetal calf serum (FCS) in Dako buffer (Dako). Primary antibodies were applied in 10 % FCS/Dako buffer at 4 °C overnight. Secondary antibodies biotinylated anti-rabbit 1:1500 (Jackson; 712065152) or anti-rat (Jackson; 712065153) were applied for 1 h at room temperature (RT) in 10 % FCS/Dako buffer. Finally, the sections were incubated with avidin peroxidase (1:100, Sigma Aldrich) in 10 % FCS/Dako buffer for 1 h at RT. Antibody binding was routinely visualized using DAB (Sigma Aldrich). The sections were counterstained with haematoxylin, dehydrated and mounted in Eukitt. Quantification of immunoreactive cells (Fig 6B) were performed on sections of the lumbar spinal cord per animal at a magnification of 20× in a microscopic filed of 0.27 mm2, which covered the entire anterior horn (grey matter) and the adjacent anterior column (white matter). Values presented in Fig. 6B were re-calculated as cells per mm2 of tissue.

Figure 6. Genetic ablation of miR-155 prevents M1-polarization in spinal cord microglia from SOD1 mice.

(A) Representative immunihistochemical micrographs of lumbar spinal cords of Non-Tg/miR-155−/−, SOD1/miR-155+/− and SOD1/miR-155−/− female mice (n = 4) at 117 days of age. Scale bars represent 50 μm. (B) Quantification of immunoreactive cells in the entire anterior horn (grey matter) and the adjacent anterior column (white matter). Values represent cells/mm2 (mean ± s.e.m) (one-way ANOVA; Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons test).

Mass spectrometry analysis: Protein extraction, digestion and tandem mass tagging (TMT) labeling

Cerebrospinal fluid (1:1 equal volume with lysis buffer), spinal cord and spleen tissues were mechanically lysed with a homogenizer with SDS lysis buffer [2.5 % SDS w/v, PhosStop (Roche, Madison, WI) phosphatase inhibitors, EDTA free protease inhibitor cocktail (Promega, Madison, WI) and 50 mM HEPES, pH 8.5]. Lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min, reduced with 5 mM DTT and cysteine residues were alkylated with iodoacetamide (14 mM) as previously described.32 Protein content was separated from impurities by methanol-chloroform precipitation. Protein pellets were resuspended in 8 M Urea containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 8.5) and concentrations were measured by BCA assay (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) prior to protease digestion. Protein lysates were diluted to 4 M urea and digested with LysC (Wako, Japan) in a 1/100 enzyme/protein ratio overnight (RT) or subjected to sequential LysC and trypsin protease digestion. Protein extracts undergoing sequential digestion were diluted further to a 1.5 M urea concentration and trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI) was added to a final 1/200 enzyme/protein ratio for 6 hours at 37 °C. Digests were acidified with 20% formic acid (FA) to a pH ~ 2 and subjected to C18 solid-phase extraction (SPE) (Sep-Pak, Waters, Milford, MA).

Isobaric labeling of the digested peptides was accomplished with 6-plex or 10-plex tandem mass tag (TMT) reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). Reagents, 0.8 mg, were dissolved in 42μl dry acetonitrile (ACN) and 10 μl was added to 100 μg of peptides dissolved in 100 μl of 200mM HEPES, pH 8.5. After 1hr (RT), the reaction was quenched by adding 4 μl of 5% hydroxylamine. Labeled peptides were combined, acidified with FA (pH ~2) and diluted to a final ~5% ACN concentration prior to C18 SPE on Sep-Pak cartridges (100 mg).

Data normalization and analysis

Heatmaps were generated employing Multi Experiment Viewer v 4.8. Expression values were transformed using the mean and standard deviation of the row (gene) of the matrix to which the value belongs, using the following formula: Value = [(Value) − Mean(Row)]/[Standard deviation(Row)]. Hierarchical clustering analysis was performed using Pearson correlation (average linkage clustering method). K-means clustering used Pearson correlation for distance measures.

IPA (Ingenuity®) analysis

Data were analyzed through the use of IPA (Ingenuity® Systems, www.ingenuity.com). Differentially expressed genes and miRNAs (with corresponding fold-changes and P values) were incorporated in canonical pathways and bio-functions and were used to generate biological networks. Uploaded dataset for analysis were filtered using the following cutoff definitions: 1.5-fold change, P<0.05 (in human datasets).

Nanostring mouse microglia MG400 chip design

The MG400 chip was designed using quantitative Nanostring nCounter platform as described previously.29

Nanostring human microglia MG447 chip design

The MG447 chip was designed using quantitative Nanostring nCounter platform based on MG400 chip. The chip includes 447 genes related to: 1) 376 microglial genes; 2) 40 inflammation genes which we found affected in microglia in mouse models of SOD1, EAE and AD; 3) 25 known/predicted miR-155 targeted genes and 4) 6 housekeeping genes (see Supplementary Table 5).

Quantitative Nanostring nCounter miRNA/gene expression profile

Nanostring nCounter technology (www.nanostring.com) allows expression analysis of multiple genes (up to 800 genes) from a single sample. We performed nCounter multiplexed target profiling of inflammation genes in mice (nCounter® Mouse Inflammation Kit) and immune genes in human (nCounter® GX Human Immunology Kit) which consist of genes differentially expressed during inflammation and immune responses, nCounter miRNA (nCounter Mouse and Human miRNA Assay Kits) and Nanostring MG400 and MG447 microglia chips (see above). 100 ng per samples of total RNA were used in nCounter analysis according to the manufacturer’s suggested protocol.

Statistical analysis

Unless otherwise indicated, data are presented as means ± s.e.m. and two-tailed Student’s t-tests (unpaired) or ANOVA multiple comparison tests were used to assess statistical significance (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001) and calculated with GraphPad Prism 6 software (La Jolla, CA).

Study approval

Animal protocols were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Harvard Medical School and are according to NIH guidelines. Concerning the use of human materials, the study was approved by the MGH and BWH institutional review boards and all subjects who provided cerebrospinal fluid underwent informed consent prior to being enrolled in the study. ALS patients were at least 18 years old and met El Escorial Criteria for possible, probable, or definite ALS.

Accession codes

The gene and miRNA data have been deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under the ID code GSE52947 and protein data has been deposited in PeptideAtlas under the ID code PASS00368.

RESULTS

The unique molecular signature that characterizes microglia is lost in SOD1G93A mice

We have previously identified a unique molecular signature in adult microglia (M0) encompassing both genes, microRNAs and proteins,29 which represent so called ‘resting’ state of microglia.33 The identification of a molecular microglial signature can now be used to determine the features that account for microglia CNS homeostatic function, as well as neurotoxic versus protective properties. Using this signature, we generated a Nanostring-based microglia chip termed MG400 which contains unique and enriched microglial genes and known inflammatory genes. Furthermore, we generated two microglial specific antibodies (FCRLS and P2RY12) which react with resident microglia, but not with infiltrating monocytes or macrophages.29 We used anti-FCRLS mAb to sort microglia from the spinal cord of SOD1 mice during various stages of disease progression and we profiled the microglia using the MG400 chip. We found that 224 microglia specific genes were significantly downregulated in SOD1 mice vs. wild type (WT) littermates. 78 genes were downregulated beginning at 30 days of age and 146 genes were downregulated beginning at age 60 days of age. In addition, 16 genes related to inflammation including Apoe, Ccl2, Axl and Csf1 were upregulated (Supplementary Table 1). Importantly, most of the unique 106 microglial genes which we identified previously29 were downregulated beginning at 30 days of age. Moreover, all microglial transcription factors including Egr1, Fos and Atf3 were significantly downregulated (Fig 1A and Supplementary Table 1). Concomitant with this, upstream regulators such as Tgfb1 and Tgfbr1 which we found to have a crucial biological function in the development of microglia29 were downregulated beginning at 30 days of age. In addition, Mertk and Gas6, which play an important role in suppression of innate inflammatory pathways34 were significantly downregulated (Fig 1B). qPCR analysis confirmed the downregulation of the microglial specific gene P2ry12 and suppression of Tgfb1 and Tgfbr1, and upregulation of Apoe (Fig 1C). Immunohistochemical analysis using the P2ry12 microglia specific antibody29 showed complete loss of signal in the spinal cord at end-stage disease (Fig 1D). Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) based on the MG400 profile showed that the TGFβ network was suppressed in spinal cord microglia (Fig 1E). Most microglial biological functions were suppressed; at early stages of disease, pathways related to phagocytosis were most significantly downregulated whereas at later stages of disease, pathways related to cellular homeostasis were downregulated. On the other hand, genes related to chemotaxis of macrophages including Apoe, C3ar1, Ccl2, Ccl4, Csf1 and Tlr2 were upregulated (Table 1).

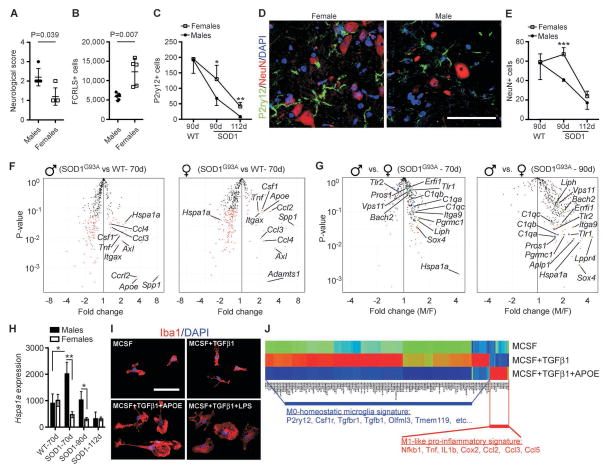

Figure 1. The unique molecular signature that characterizes microglia is lost in SOD1G93A mice.

(A) Heatmap of significantly affected 78 enriched and unique microglial genes P<0.05, Student’s t test, 2-tailed. (B) Gene expression of selected microglial specific molecules as measured by MG400 chip. (C) qPCR validation of P2ry12, Tgfb1, Tgfbr1 and Apoe genes. Bars show mean ± s.e.m (n = 5). Shown is one representative of two individual experiments. (D) Representative immunofluorescent images of P2ry12+ resident microglia, NeuN+ neurons co-stained with nuclear staining (DAPI) in ventral horn of WT and SOD1G93A mice at end-stage. Scale bars represent 50 μm. (E) IPA analysis shows inhibition of TGFβ pathway related molecules in spinal cord microglia from SOD1 mice at end-stage. For each molecule in the dataset the expression fold change as compared to spinal cord microglia from WT littermates is presented. Legend shows prediction state and relationships.

TABLE 1.

Spinal cord samples - Demographic and clinical features of study participants.

| Characteristic | ALS (n=10)a | Controls (n=10) |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years ± SD | 60.2 ± 9.5 | 65.9 ± 13.6 |

|

| ||

| Male/Female ratio | 7:3 | 5:5 |

|

| ||

| Disease duration (months) ± SDb | 31.6 ± 22.2c | N/A |

|

| ||

| Mean post mortem (PMI) interval (hours) ± | 18.4± 6.2d | 32.2 ± 21.6d |

|

| ||

| Site of Disease Onset | ||

| Bulbar | 0% (n=0) | N/A |

| Cervical | 30% (n=3) | N/A |

| Lumbar | 60% (n=6) | N/A |

| Unknown | 10% (n=1) | N/A |

8 sALS subjects and 2 fALS subjects.

Disease onset taken as the first of the month for subjects who could identify the month, but not the day of disease onset.

Disease duration unknown for 2 ALS subjects.

PMI unknown for 1 ALS subject and 1 control subject.

Disease duration: time from symptoms onset to death.

We performed microRNA target scan analysis based on the MG400 profile and identified miR-155 as the most significantly activated (P = 3.52E-08) based on multiple direct targets of microglial genes (Supplementary Table 2). These findings are consistent with our previous observation that miR-155 was the most upregulated miRNA in spinal cord microglia from SOD1G93A mice.8 Importantly, Csf1r is among the genes directly targeted by miR-15535, 36 and it is known that microglia are absent in Csf1r−/− mice37 or mice treated with CSF1R inhibitors.38 In summary, we found profound loss of the unique molecular and functional signature in microglia associated with disease progression in SOD1G93A mice.

Identification of molecular signature in human lumbar ventral horn and CSF from ALS subjects

In order to determine the molecular signature in human ALS and to compare it to our findings in the SOD1G93A mice, we extensively profiled human lumbar spinal cords from healthy control (HC) and ALS subjects (Table 2) by Nanostring microRNA and gene profile, quantitative protein mass spectrometry and RNA-seq analysis. We found 117 dysregulated microRNAs in ALS subjects (P<0.05) (Supplementary Table 3). Among the upregulated microRNAs, miR-155 was the most upregulated microRNA (9.1 fold as compared to healthy controls). Increased expression of miR-155 in both sALS and fALS forms of ALS was validated by qPCR (Fig 2A). Nanostring profiling of immune genes identified 44 genes which were significantly affected (P<0.05) (Supplementary Table 4). In addition we profiled lumbar ventral horn from HC and ALS subjects with our newly generated human microglial chip (MG447) based on the MG400 chip.29 We found 116 dysregulated genes in ALS subjects (P<0.05) (Supplementary Table 5). 20 genes were upregulated including APOE, APOD and APOC1 (Fig 2B) and 96 microglial genes were downregulated. Among the downregulated genes we identified JARID2 and CSF1R (Fig 2C), which were previously validated as direct targets of miR-155.18 Consistent with a decreased expression of Entpd1 and P2ry12 genes in spinal cord microglia in SOD1 mice (Fig 1A) we found that these microglial specific genes29 were significantly downregulated in spinal cord from ALS subjects (Fig 2D).

Figure 2. Identification of molecular signature in human lumbar ventral horn from ALS subjects.

(A) qPCR validation of miR-155. Relative expression in HC (black circles), sALS (black squares) and fALS (red squares) were calculated using the comparative Ct (2-ΔΔCt) method. miRNA expression level was normalized against U6 miRNA. PCRs were run in triplicates per subject. Each data point represents an individual subject. (B) qPCR validation of upregulated APOE, APOD and APOC1 genes. (C) qPCR validation of downregulated miR-155 direct gene targets CSF1R and JARID2. (D) qPCR validation of downregulated microglia specific ENTPD1 and P2RY12 genes. PCRs were run in triplicates per subject. Each data point represents an individual subject. Horizontal bars denote mean ± s.d. Statistical analysis by Student’s t test, 2-tailed. (E) Apolipoproteins relative expression as measured by TMT-quantitative proteomics (see Supplementary Table 6). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.01, Student’s t test, 2-tailed. (F) Western blot analysis of APOE in human lumbar spinal cords. (G) Immunohistochemical analysis of APOE in human ventral horn spinal cord from HC, fALS and sALS subjects.

Quantitative TMT mass spectrometry analysis identified significantly dysregulated (P<0.05) 552 proteins in ALS subjects (Supplementary Table 6). The major upregulated proteins identified were related to the apolipoprotein family molecules (Fig 2E). Western blot analysis also demonstrated increased APOE in the spinal cord of ALS subjects (Fig 2F). Concurrent with this, immunohistochemical analysis of APOE in human ventral horn from fALS and sALS subjects showed increased signal in all ALS specimens (Fig 2G).

Our data are consistent with a recent report that APOE is upregulated in microglia in SOD1 mice.39 In addition, we performed quantitative mass spectrometry of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples from sALS and fALS subjects and found increased levels of APOB, APOC1, APOD, APOF and APOE in both sALS and fALS (Supplementary Table 7). Moreover, we performed RNA-seq analysis of lumbar spinal cord tissue from sALS and fALS (Supplementary Table 8) and compared the affected genes to our proteomic data set (Supplementary Table 6). We found the identical 21 upregulated and 23 downregulated molecules in the analysis of both data sets (Table 4). Among these molecules, APOE, APOC1 and S100A6 were significantly upregulated. Interestingly, S100A6 has been found highly expressed in SOD1 mice and ALS subjects40 and enhances SOD1 aggregation.41 Moreover, molecules related to myelin including PLP1 and MOBP were significantly downregulated. These findings are consistent with a recent study reporting degeneration of oligodendrocytes in ALS.42 Based on the identified molecular signature in human lumbar spinal cords from ALS subjects we performed IPA analysis of biological functions and found that the most significantly affected function is related to movement disorders (P = 2.76E-24).

Table 4. Similarly affected genes and proteins in lumbar spinal cord from ALS subjects.

21 upregulated and 23 downregulated molecules of at least 1.5 fold in both datasets identified by quantitative proteomics analysis (see Supplementary Table 6) and RNA-se

| Gene Symbol | Entrez Gene Name | Location | Type | Fold change RNASeq | Fold change protein | p value RNASeq | p value protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Upregulated molecules | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| TSTD1 | thiosulfate sulfurtransferase (rhodanese)-like domain containing 1 | Cytoplasm | other | 4.1 | 1.5 | 2.63E-02 | 2.29E-03 |

| RBP4 | retinol binding protein 4, plasma | Extracellular Space | transporter | 3.6 | 4.2 | 2.41E-02 | 3.39E-03 |

| C10orf116 | adipogenesis regulatory factor | Nucleus | other | 3.2 | 2.5 | 6.36E-04 | 7.33E-04 |

| APOC1 | apolipoprotein C-l | Extracellular Space | transporter | 2.7 | 3.2 | 1.67E-05 | 1.73 E-02 |

| S100A4 | S100 calcium binding protein A4 | Cytoplasm | other | 2.7 | 3.9 | 2.02E-04 | 5.91E-05 |

| LYZ | lysozyme | Extracellular Space | enzyme | 2.6 | 1.9 | 1.06E-04 | 7.27E-03 |

| HP | haptoglobin | Extracellular Space | peptidase | 2.5 | 3.0 | 7.37E-03 | 3.60E-02 |

| APOE | apolipoprotein E | Extracellular Space | transporter | 2.5 | 1.9 | 4.08E-05 | 4.50E-05 |

| LSP1 | lymphocyte-specific protein 1 | Cytoplasm | other | 2.5 | 3.1 | 9.30E-03 | 5.29E-03 |

| PDLIM4 | PDZ and LIM domain 4 | Plasma Membrane | other | 2.4 | 1.6 | 1.52E-03 | 1.68E-02 |

| MATN2 | matrilin 2 | Extracellular Space | other | 2.3 | 3.9 | 1.03E-03 | 1.92E-02 |

| SOD3 | superoxide dismutase 3, extracellular | Extracellular Space | enzyme | 2.2 | 2.7 | 7.25E-03 | 7.62E-03 |

| LGALS3 | lectin, galactoside-binding, soluble, 3 | Extracellular Space | other | 2.1 | 3.1 | 1.40 E-03 | 1.32E-02 |

| COL6A2 | collagen, type VI, alpha 2 | Extracellular Space | other | 2.1 | 2.4 | 1.70E-02 | 1.11E-02 |

| S100A6 | S100 calcium binding protein A6 | Cytoplasm | transporter | 2.0 | 2.1 | 3.90E-04 | 1.39E-02 |

| TAGLN2 | transgelin 2 | Cytoplasm | other | 1.8 | 1.7 | 9.14 E-03 | 5.91E-03 |

| CLIC1 | chloride intracellular channel 1 | Nucleus | ion channel | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.74E-02 | 2.83E-02 |

| C7 | complement component 7 | Extracellular Space | other | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.49E-02 | 4.01E-02 |

| ANXA2 | annexin A2 | Plasma Membrane | other | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.58E-02 | 7.84E-03 |

| VIM | vimentin | Cytoplasm | other | 1.7 | 3.0 | 2.63E-02 | 9.26E-03 |

| PTGDS | prostaglandin D2 synthase 21kDa (brain) | Cytoplasm | enzyme | 1.5 | 1.5 | 2.92E-02 | 3.19E-03 |

|

| |||||||

| Downregulated molecules | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| MAOA | monoamine oxidase A | Cytoplasm | enzyme | −1.5 | −1.7 | 3.65E-02 | 1.86E-03 |

| MT-CO2 | cytochrome c oxidase subunit II | Cytoplasm | enzyme | −1.6 | −2.0 | 8.15E-03 | 3.04E-04 |

| SLC39A10 | solute carrier family 39 (zinc transporter), member 10 | Extracellular Space | transporter | −1.6 | −2.0 | 3.16E-02 | 1.54E-02 |

| TBC1D4 | TBC1 domain family, member 4 | Cytoplasm | other | −1.7 | −1.7 | 7.80 E-03 | 5.85E-03 |

| DNM3 | dynamin 3 | Cytoplasm | enzyme | −1.8 | −1.7 | 4.50 E-02 | 2.41E-03 |

| SLC1A2 | solute carrier family 1 (glial high affinity glutamate transporter), member 2 | Plasma Membrane | transporter | −1.8 | −2.0 | 1.00E-02 | 2.04E-03 |

| FMNL2 | formin-like 2 | Cytoplasm | other | −1.8 | −1.7 | 3.35E-02 | 2.20E-03 |

| PLP1 | proteoliprd protein 1 | Plasma Membrane | other | −1.8 | −2.0 | 3.95E-02 | 8.48E-03 |

| STK39 | serine threonine kinase 39 | Nucleus | kinase | −1.9 | −1.7 | 4.40 E-02 | 1.30E-02 |

| CDK18 | cyclin-dependent kinase 18 | Cytoplasm | kinase | −1.9 | −1.7 | 4.44E-02 | 3.05E-03 |

| MT-CYB | cytochrome b | Cytoplasm | enzyme | −1.9 | −1.7 | 2.46E-04 | 1.01E-02 |

| CLDND1 | claudin domain containing 1 | Plasma Membrane | other | −2.0 | −1.7 | 2.24E-02 | 4.38E-02 |

| PIP4K2A | phosphatidyliinositol-5-phosphate 4-kinase, type II, alpha | Cytoplasm | kinase | −2.0 | −1.7 | 8.06E-03 | 3.47E-04 |

| PKP4 | plakophilin 4 | Plasma Membrane | other | −2.3 | −1.7 | 3.79E-05 | 1.05E-02 |

| ENPP6 | ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 6 | Cytoplasm | enzyme | −2.3 | −2.0 | 2.63E-02 | 1.13E-03 |

| ANLN | anillin, actin binding protein | Cytoplasm | other | −2.4 | −2.0 | 1.51E-03 | 5.79E-03 |

| MOBP | myelin-associated oligodendrocyte basic protein | Cytoplasm | other | −2.5 | −2.0 | 4.48E-05 | 2.90E-03 |

| DNAJA4 | DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily A, member 4 | Nucleus | other | −2.6 | −1.7 | 9.77E-05 | 1.36E-02 |

| PLCL1 | phospholipase C-Ike 1 | Cytoplasm | enzyme | −2.6 | −2.0 | 5.97E-04 | 1.34E-03 |

| MT-ND2 | MTND2 | Cytoplasm | enzyme | −2.9 | −2.0 | 2.36E-07 | 1.79E-05 |

| KCNJ16 | potassium inwardly-rectifying channel, subfamily J, member 16 | Plasma Membrane | ion channel | −2.9 | −2.5 | 9.30E-05 | 3.60E-02 |

| GJB6 | gap junction protein, beta 6, 30kDa | Plasma Membrane | transporter | −3.2 | −2.0 | 1.32E-04 | 3.91E-02 |

| HSPH1 | heat shock 105kDa/110kDa protein 1 | Cytoplasm | other | −6.4 | −1.4 | 1.50E-13 | 1.22E-02 |

Genetic ablation of miR-155 delays disease onset and extends survival in SOD1 mice

To assess the role of miR-155 in the SOD1 model of ALS, SOD1G93A on a B6 congenic background (high transgene copy number) were bred with non-Tg C57Bl/6 miR-155−/− mice. Non-transgenic miR-155−/− were then backcrossed to F1-SOD1G93A/miR-155−/+ to produce F2-SOD1G93A/miR-155−/− and SOD1G93A/miR-155+/− mice which had a deletion of one or two miR-155 alleles. We found that genetic ablation of miR-155 prolonged survival by 51 days in females (n=9–10/group) and by 27 days in males (n=9–10/group) (Fig 3A), extended time to reach a neurologic score of one by 62 days in females and 58 days in males, (Fig 3B and Supplementary Movie 1), enhanced rotarod performance (Fig 3C), reduced body weight loss (Fig 3D), and delayed early and late disease onset in females (Fig 3E). Interestingly, late phase was not significantly affected by genetic ablation of miR-155 in males (Fig 3F). Cumulative results of statistical analysis of SOD1G93A/miR-155−/+ and SOD1G93A/miR-155−/− mice in females and males are shown in Fig 3G.

Figure 3. Genetic ablation of miR-155 delays disease onset and extends survival in SOD1 mice.

(A) Kaplan-Meier analysis of the probability of surviving as function of age in SOD1/miR-155+/− and SOD1/miR-155−/− mice. Mantel-Cox’s F-test comparison showed prolonged survival by 51 days (P < 0.0001) in SOD1/miR-155−/− (n = 10) vs. SOD1/miR-155+/− (n = 10) female and prolonged survival by 27 days (P < 0.0001) in SOD1/miR-155−/− (n = 10) vs. SOD1/miR-155+/− (n = 9) male mice. (B) Time-to-event analysis for disease neurologic onset (neurological severity score of 1 and 2). Of note, neurologic scores 1 and 2 were based on the Prize4Life ‘Working with ALS Mice’ guidelines. (C) Rotarod performance as a function of age in female and male mice. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. (D) Weight loss plotted for SOD1/miR-155+/− and SOD1/miR-155−/− female and male mice. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. (E) Duration of an early disease phase (drop of 5% of the mouse maximal weight) and a later disease phase (from 5% weight loss to end-stage) in females (E) and males (F). Data represent mean ± s.e.m. Student’s t test, 2-tailed. (G) Cumulative results of statistical analysis of SOD1G93A/miR-155−/+ and SOD1G93A/miR-155−/− groups in females and male mice.

Early activation of inflammatory genes in microglia correlates with disease severity in SOD1 males

We found that genetic ablation of miR-155 had greater effect on female survival (51 days) as compared to males (27 days) SOD1 mice. Previous work reported a gender effect on lifespan in SOD1 mouse models, with an accelerated disease progression and shortened lifespan in male mice.43, 44 Since the loss of the unique microglia molecular signature was associated with disease progression in SOD1G93A mice (Fig 1), we further investigated whether dysregulated gene expression in microglia is linked to gender in the SOD1 model. At the age of 112 days SOD1 males show a higher neurological score compared to females (Fig 4A). We found that the absolute number of FACS-sorted FCRLS+ microglia in the spinal cord was lower in SOD1 males as compared to females (Fig 4B). When we used an additional microglial specific marker (P2ry12) to analyze resident microglia29 by immunohistochemical analysis we also found that the number of P2ry12+ microglia was lower at 90 and 112 days in males as compared to females (Fig 4C). In addition, P2ry12+ microglia in males exhibited a more dystrophic morphology associated with deramified, atrophic and fragmented processes as compared to females at 112 days of age (Fig 4D). Furthermore, the number of NeuN+ neurons was lower in males at 90 days of age (Fig 4E) than in females. Next, we performed gene expression profiling using the MG400 microglial chip of FACS-sorted FCRLS+ spinal cord microglia from SOD1 males and females vs. gender matched WT-littermates. At 70 days of age (presymptomatic stage) SOD1 males showed greater upregulation of inflammatory genes as compared to females (Fig 4F). Among these genes Apoe and Spp1 (osteopontin) were the most upregulated in males (Fig 4F and Supplementary Table 9). Next, we compared the gene expression profile of SOD1 males vs. females at presymptomatic (70d) and onset (90d) stages. We found that males had higher expression of inflammatory genes including TLR and complement signaling related proteins. This trend was increased at 90 days of age (Fig 4G). Interestingly, Hspa1a (HSP70) was significantly downregulated in SOD1 females starting at 30d of age as compared to WT females (Fig 1B), whereas in males, the expression of Hspa1a was significantly upregulated at 70d and downregulated at 112d of age (Fig 4H).

Figure 4. Gender differences in SOD1 mice.

(A) Neurologic score in B6/SJL-SOD1G93A males and females mice at 112 days of age. (B) Absolute numbers of sorted FCRLS+ microglia from spinal cord of SOD1 males (n = 5) and females (n =5) at 112d of age. Student’s t test, 2-tailed. (C) Quantitative analysis of P2ry12+ microglia. (D) Representative immunofluorescent images of P2ry12+ microglia and NeuN+ neurons co-stained with nuclear staining (DAPI) in lumbar level ventral horn from SOD1G93A female and male mice at 112d of age. Scale bars represent 60 μm. (E) Quantitative analysis of NeuN+ neurons in ventral horn lumbar level from WT and SOD1 males (n = 5) vs. females (n =5) at 90d and 112d of age. Data represents mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, by factorial ANOVA and Fisher’s post hoc test. (F) Volcano plots based on Nanostring MG400 expression data from SOD1 spinal cord sorted FCRLS+ microglia. Red dots show significantly affected genes (p<0.05 by Student’s t test, 2-tailed). (G) Volcano plots based on Nanostring gene expression data from SOD1 spinal cord sorted FCRLS+ microglia (see complete gene expression data in Supplementary Table 9). (H) Hspa1a gene expression based on Nanostring MG400 chip analysis. (I) Representative confocal images of adult spinal cord microglia stained with Iba1 and DAPI. Microglia were cultured for 5 days in the presence of MCSF or MCSF+TFGβ1 and treated for additional 24h with recombinant APOE (100ng/ml) or LPS (100ng/ml). Similar results were obtained in five independent experiments. (J) Heatmap of significantly affected microglial genes based on Nanostring MG400 expression profile in WT cultured adult microglia treated with MCSF, TGFB1 and APOE (complete gene expression data show in Supplementary Table 12). Each lane represents mean of two different experiments with pooled spinal cord microglia (n = 5 mice per group).

APOE suppresses the M0-microglia signature and induces a M1-like phenotype

As described above, we identified gender differences in SOD1 mice associated with significant upregulation of inflammatory genes including Apoe. APOE regulates cholesterol and lipid metabolism in the brain, but has also been implicated in regulating inflammatory responses in neurodegenerative disorders.45 However, the underlying molecular mechanism of APOE related neuroinflammation regulation in microglia is unknown. We recently found that Apoe gene expression is downregulated in microglia during development and inversely correlated with the induction of the M0-unique microglia signature.29 In addition, we found that suppression of microglial genes was associated with an increase of Apoe, which was one of the most upregulated molecules in spinal cord microglia from SOD1 mice (Fig 1B and C and Supplementary Table 1) as well in spinal cord and CSF from ALS subjects (Fig 2 and Supplementary Tables 6–8). Thus, we investigated whether APOE suppresses the M0-unique signature in microglia. We found that adult microglia incubated with recombinant APOE (100ng/ml) changed their morphology from resting bipolar to the amoeboid form within 24h (Fig 4I). MG400 analysis showed that APOE induced expression of M1-associated molecules including NfkB, Tnfa, Il1b, Ccl2, Ccl3 and Ccl5 and suppressed M0-microglia molecules including Csf1r, Tgfb1 and Tgfbr1 (Fig 4J) which are essential for microglia development29 and survival.37, 38

Genetic ablation of miR-155 reverses the abnormal molecular signature of microglia and splenic monocytes in SOD1 mice

To investigate the role of miR-155 on spinal cord microglia molecular signature abnormalities, we performed FACS analysis for resident microglia using anti-FCRLS mAb which recognizes resident microglia.29 We showed previously that CD39+ microglia undergo apoptosis and are reduced in the spinal cord of SOD1G93A mice.8 A decrease in CD39 (Entpd1 gene) both in mouse (Fig 1A) and human (Fig 2D) could lead to the inability to identify resident microglia using anti-CD39 antibody. Furthermore, we could not use anti-P2ry12 antibody as P2ry12 gene expression was decreased during disease progression (Fig 1B and C) and protein expression is absent in spinal cord microglia from SOD1 mice at end-stage (Fig 1D). Thus, because the Fcrls gene expression is not decreased during disease progression in SOD1 mice (Fig 1B), we used anti-FCRLS mAb to isolate resident microglia. FACS analysis demonstrated decreased number of CD11b+/FCRLS− cells and increased number of CD11b+/FCRLS+ microglia in SOD1G93A/miR-155−/− mice (Fig 5A and B). Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated significant increase of NeuN+ neurons in the ventral horn in SOD1G93A/miR-155−/− vs. SOD1G93A/miR-155+/− mice (Fig 5C). We then profiled spinal cord microglia and splenic Ly6CHi monocytes, which we previously found to have a pro-inflammatory profile.8 Genetic ablation of miR-155 in SOD1 mice reduced the expression of 16 pro-inflammatory genes including Tnf, Fasl, Ccl2 and Nos2 in spinal microglia (Fig 5D) and 14 proinflammatory genes including Tnf, Il1b, Fasl, Nos2 and Ccr2 in Ly6CHi splenic monocytes by at least two-fold (Fig 5E and Supplementary Table 10).

Figure 5. Genetic ablation of miR-155 reverses the abnormal microglia gene/miRNA signature and functions in SOD1 mice.

(A) Representative FACS analysis of spinal cord-derived mononuclear cells stained with FCRLS (resident microglia) and CD11b (myeloid cells). Note, increased number of FCRLS−/CD11b+ cells in SOD1/miR155+/+ (n = 3) or SOD1/miR155+/− (n = 5) in comparison to SOD1/miR155−/− (n = 5) mice. (B) Absolute number of sorted cells per spinal cord. (C) Quantification of NeuN+ cells in ventral horn of WT non-Tg/miR-155+/+ (n = 4) at age of 117d, SOD1/miR-155+/− (n = 4) and SOD1/miR155−/− (n = 4) mice. Data represents mean ± s.d. Student’s t test, 2-tailed. Nanostring inflammation chip analysis in (D) spinal cord microglia and (E) splenic Ly6CHi monocytes. (F) MG400 profile in spinal cord microglia. (G) Top-50 dysregulated microglial genes are shown. Bars show fold difference vs. Non-Tg/miR-155+/− mice. (H) miRNA profile in spinal cord microglia. (I) 41 dysregulated miRNAs are shown. Bars show fold difference vs. Non-Tg/miR-155+/− mice. For complete gene/miRNA data see Supplementary Table 10. Data are representative of three different experiments with cells pooled from Non-Tg/miR-155+/− (n = 4), SOD1/miR-155+/− (n = 5) and SOD1/miR155−/− (n = 5) female mice. Heatmap and hierarchical clustering shows dysregulated genes of at least two fold.

As described above, we found that the unique molecular microglia signature is lost in SOD1G93A mice (Fig 1). To investigate the effect of miR-155 on these microglial abnormalities, we profiled gene expression of sorted FCRLS+ spinal cord microglia from non-Tg/miR-155+/−, SOD1/miR-155+/− and SOD1/miR-155−/− mice. We found that deletion of miR-155 in SOD1 mice derepressed 240 microglial genes and reduced the expression of genes such as Ccl2, Ccl4, Axl and Apoe (Fig 5F). Figure 5G shows the derepression effect of miR-155 deletion on the top 50 (of 240) microglial specific genes. Of note, miR-155 deletion also induced the expression of some genes to a level above the expression in non-Tg/miR-155+/− mice (Fig 5G). The miRNA profile in spinal cord microglia showed that 70 affected miRNAs were restored in SOD1/miR-155−/− mice (Fig 5H and I). We then performed immunohistochemical analysis of the spinal cord in which we stained for iNOS (Nos2; inducible nitric oxide synthase, M1 marker46) and P2RY12 (M0 unique microglial marker29) in SOD1/miR-155+/− mice as compared to SOD1/miR-155−/− mice and control mice (Non-Tg/miR-155−/−). Of note, no differences were observed between Non-Tg/miR-155−/− and WT mice. As shown by staining and quantification, we found a decrease in P2RY12 and an increase in iNOS in SOD1miR-155+/− mice and this was restored in SOD1/miR-155−/− mice (Fig 6A and B). Most of the directly targeted miR-155 genes were derepressed in SOD1/miR-155−/− mice (Fig 7A). The transcription factors which we found as the most highly enriched in microglia Egr1, Atf3, Jun, Fos, and Mafb29 were derepressed by targeting miR-155 in SOD1 mice including Csf1r and Tgfbr1 upstream regulators essential for microglia development and survival. 29, 37, 38 Moreover, out of 73 microglial genes which we found significantly downregulated in spinal cord microglia from SOD1 mice beginning at 30 days of age (Fig 1A), 66 genes were derepressed at least 1.5-fold in SOD1/miR-155−/− mice as compared to SOD1/miR-155+/− mice (Supplementary Table 10). Major biological functions, such as maturation of phagocytes and chemotaxis of macrophages, which were dysregulated in microglia from SOD1 mice (Table 1) returned to the normal levels observed in non-Tg mice in SOD1/miR-155−/− mice (Fig 7B and Supplementary Table 10).

Figure 7. Genetic ablation of miR-155 derepresses targeted genes in spinal cord microglia from SOD1 mice.

(A) Derepressed miR-155-targeted genes in SOD1/miR-155−/− mice. Bars show expression relative to Non-Tg/miR-155+/− female mice (dashed line). (B) Microglial functions in SOD1/miR-155+/− and SOD1/miR-155−/− mice. IPA functional analysis based on early and late downregulated and upregulated genes detected with MG400 chip.

Genetic ablation of miR-155 reverses the abnormal molecular signature of spinal cord in SOD1 mice

We also investigated whether targeting of miR-155 had a global effect on the abnormal molecular signature in whole lumbar spinal cord tissue in SOD1 mice. We performed quantitative mass spectrometry proteomic analysis on lumbar spinal cord from non-Tg/miR-155+/−, SOD1G93A/miR-155+/− and SOD1G93A/miR-155−/− mice. We found that out of 142 affected proteins we identified in SOD1G93A/miR-155+/− mice, 102 were restored by at least 1.5-fold in SOD1G93A/miR-155−/− mice (Supplementary Table 11). Among these proteins, Apod, Apoe and S100a6 were restored approximately to the level of non-Tg/miR-155+/− mice (Fig 8A). Although SOD1 protein expression was high in both SOD1G93A/miR-155+/− and SOD1G93A/miR-155−/− mice as compared to non-Tg/miR-155+/− mice, the level of SOD1 expression was not affected by miR-155 deletion (Fig 8B). We also observed normalization of the abnormal miRNA signature in lumbar spinal cord of SOD1 mice (Fig 8C and Supplementary Table 11).

Figure 8. Genetic ablation of miR-155 reverses the abnormal miRNA and proteomic signatures of spinal cord in SOD1 mice.

(A) 57 derepressed proteins by at least two-fold in SOD1G93A/miR-155−/− vs. SOD1G93A/miR-155+/− female mice. Bars show expression relative to Non-Tg/miR-155+/− female mice. (B) Upregulated proteins in SOD1 mice which are not affected by genetic ablation of miR-155. (C) 56 derepressed miRNAs by at least two-fold in SOD1G93A/miR-155−/− vs. SOD1G93A/miR-155+/− mice. Bars show expression relative to Non-Tg/miR-155+/− mice. For complete protein/miRNA data see Supplementary Table 11.

Genetic ablation of miR-155 restores phagocytic function of microglia in SOD1 mice

We found that pathways related to phagocytic function were the most downregulated in spinal cord microglia in SOD1 mice (Table 1). It has been proposed that impaired phagocytosis by microglia occurs during aging47, in Alzheimer’s disease48 and its models,49 in multiple sclerosis50, 51 and in a mouse model of Rett syndrome.30 To investigate whether there is impaired microglia phagocytic function in SOD1 mice and whether targeting miR-155 reverses it, we measured phagocytosis of dead neurons by directly isolated microglia from the spinal cord of non-transgenic miR-155+/−, non-transgenic miR-155−/−, SOD1G93A/miR-155−/+ and SOD1G93A/miR-155−/− mice at age of 120 days. We found that microglia from SOD1G93A/miR-155+/− mice are impaired to phagocyte dead neurons and genetic ablation of miR-155 restores their phagocytic ability (Fig 9).

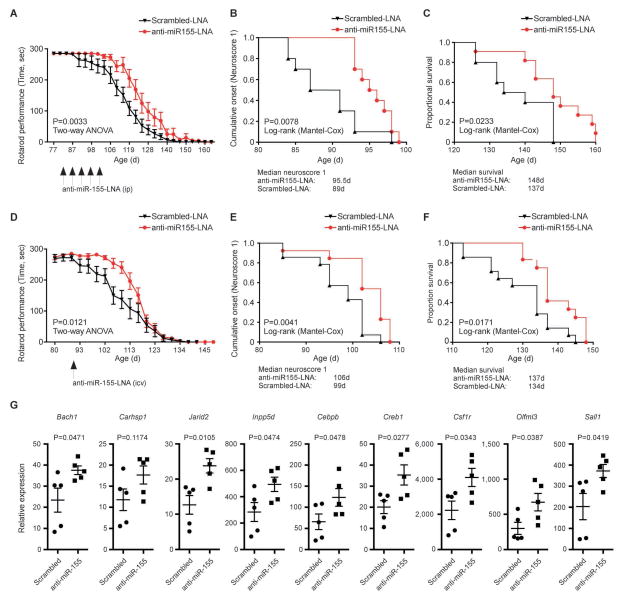

Targeting miR-155 with peripheral and centrally administered anti-miR-155 delays disease onset and extends survival in SOD1 mice

We treated SOD1 mice with anti-miR-155 given both peripherally and intraventricularly to determine if treatment affected miR-155 targeted genes and prolonged survival. Because we found overexpression of miR-155 both peripherally (monocytes) and centrally (microglia),8 we investigated the effect of targeting both of these compartments with anti-miR-155. We used Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA™) containing miRNA inhibitor, currently being tested in humans to target miR-122 in hepatitis C.52, 53 We used LNA-anti-miR-155 (5′-TcAcAATtaGmCAtTA-3′) and scrambled LNA-anti-miR-155 (5′-TcAam CATt aGAmCtTA-3′). To determine dosage, we treated diseased SOD1 mice with 0.2, 2 and 20mg/kg of anti-mIR-155 at 90 days of age, a time at which we identified a pro-inflammatory signature in splenic Ly6CHi monocytes and increased expression of miR-155.8 We used liposome complexes of the oligonucleotides and Invivofectamine31 for treatment with anti-miR-155. Three injections were given peripherally (ip) every second day. We found reversal of the inflammatory profile of Ly6CHi monocytes with both 2 and 20mg/kg as compared to PBS or scrambled anti-miR-155. An identical effect was observed with 2mg/kg given iv. No effect was observed with 0.2mg/kg. We did not find an effect of peripherally administered anti-miR-155 on the pro-inflammatory microglia profile (data not shown). After establishing the dose, we administered 2mg/kg of anti-miR-155 (ip) beginning at disease onset as defined by body weight loss of 5% of the mouse maximal weight (82 days of age) twice weekly (82d, 85d, 92d, 95d and 103d) for a total of 5 injections (ending on day 103). We found increased rotarod performance (Fig 10A), delayed time to reach a neuroscore of 1 (6.5 days) (Fig 10B) and increased survival (11 days) (Fig 10C) in peripherally treated animals.

Figure 10. Peripheral and central administration of anti-miR-155 delays disease onset and extends survival in SOD1 mice.

(A-C) SOD1G93A (B6/SJL high copy) male mice were treated peripherally (ip) with 2 mg/kg of anti-miR-155-LNA (n = 11) and 2 mg/kg of scrambled miR-155-LNA (control group) (n = 10) beginning at disease onset as defined by body weight loss (82 days of age) twice weekly. (A) Rotarod performance as a function of age. Arrows show time of injections. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. P = 0.0033, factorial ANOVA and Fisher’s post hoc test. (B) Time-to-event analysis for disease neurologic onset (neurological severity score of 1). Disease onset was significantly delayed by 6.5 days (P = 0.0078) in anti-miR-155-LNA treated mice. (C) Kaplan-Meier analysis of the probability of surviving as function of age. Mantel-Cox’s F-test comparison demonstrates increased survival by 11 days (P = 0.0233) in anti-miR-155-LNA treated mice vs. control group. (D-F) SOD1G93A (B6/SJL high copy) male mice were treated with one injection given into the lateral ventricles of 2 mg/kg of anti-miR-155-LNA (n = 13) and 2 mg/kg of scrambled miR-155-LNA (n = 14) at disease onset as defined by body weight loss (90 days of age). (D) Rotarod performance as a function of age. Arrow shows time of injection. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. P = 0.0121, factorial ANOVA and Fisher’s post hoc test. (E) Time-to-event analysis for disease neurologic onset (neurological severity score of 1). Disease onset was significantly delayed by 7 days (P = 0.0041) in anti-miR-155-LNA treated mice vs. control group. (F) Kaplan-Meier analysis of the probability of surviving as function of age. Mantel-Cox’s F-test comparison demonstrates increased survival by 3 days (P = 0.0171) in anti-miR-155-LNA treated mice vs. control group. (G) qPCR analysis of miR-155-targeted genes in FACS-sorted spinal cord FCRLS+ microglia from treated SOD1G93A (B6/SJL high copy) male mice. Mice were treated with one injection given into the lateral ventricle of 2mg/kg of anti-miR-155-LNA (n = 5) and 2mg/kg of scrabbled miR-155-LNA (n = 5) at 120 days of age. FCRLS+ microglia were sorted 5 days post-injection. Student’s t test, 2-tailed.

Next, to determine whether targeting miR-155 by central administration can restore microglia dysregulation in SOD1 mice, we administered 2mg/kg of antimiR-155 at disease onset as defined by body weight loss (90 days of age) with one injection given into the lateral ventricles. We found increased rotarod performance (Fig 10D), delayed time to reach a neuroscore of one (7 days) (Fig 10E) and increased survival (3 days) (Fig 10F). In order to determine if CSF treatment affected miR-155 targets in microglia, we sorted FCRLS+ spinal cord microglia from CNS treated animals and performed qPCR analysis. As shown in Figure 10G, we observed a derepression of miR-155 targeted genes. Thus, treatment with anti-miR-155 affects clinical disease in SOD1 mice by targeting either peripheral monocytes or brain microglia. Our results are consistent with a recent report that anti-miR-155 given in combination both peripherally and into the CNS extended survival in SOD1 mice by 10 days.54

DISCUSSION

We identified a crucial role for miR-155 in the SOD1 mouse model of ALS. Genetic ablation of miR-155 had pronounced effects both on clinical disease and the pro-inflammatory features of monocytes and microglia in SOD1 mice. In addition, we found that administration of anti-miR-155 given peripherally ameliorated disease. Genetic ablation of miR-155 reversed 72% of the dysregulated proteins in the spinal cord of SOD1 mice. These observations have direct relevance to human ALS as many of the dysregulated proteins we observed in SOD1 mice were also found dysregulated in human ALS spinal cord.

Our previous studies identified a unique microglia molecular signature related to nervous system development in which TGFβ plays a crucial role.29 Furthermore, we demonstrated that in the normal state, resident microglia are not ‘quiescent’, but are actively involved in maintaining CNS homeostasis. In the present study, we found that this microglial signature is lost during disease progression in SOD1 mice. Indeed, all microglia specific genes were downregulated except for genes related to chemotaxis of macrophages. Thus, gene expression of P2ry12, a unique microglial molecule29 was reduced in spinal cord microglia and not detected at protein level at end-stage of disease in SOD1 mice and in spinal cords from ALS subjects. In addition, CD39 gene expression was downregulated both in mice and humans. CD39 is the dominant cellular ectonucleotidase that degrades nucleotides to nucleosides, including adenosine and microglia are the only cells in the CNS which express CD39.8, 55 Microglia migrate in response to ATP and inhibition of CD39 impedes ATP triggered migration. Co-stimulation of purinergic and CD39 receptors is a requirement for microglial migration.56 Extracellular ATP can act as a mediator during inflammatory responses by binding to P2 purinergic receptors.57 CNS injury is accompanied by release of nucleotides, serving as signals for microglial activation or chemotaxis. Moreover, previous studies reported that P2ry12 is highly expressed in the ‘quiescent’ state, but dramatically reduced after microglial activation; deletion of P2ry12 diminished microglial movement following CNS injury.58 Interestingly, deletion of P2X7 receptor exacerbates gliosis and motorneuron death in the ALS model.59 We found that most microglia biological functions including phagocytic abilities and cell migration were suppressed. Thus, microglia appear to lose major homeostatic biological functions in the ALS model.

We found upregulation of apolipoproteins including APOE in microglia from SOD1 mice and increased apolipoproteins in the CSF and spinal cord tissue of both sALS and fALS subjects. Importantly, we found that gender differences in SOD1 mice were associated with early upregulation of inflammatory genes including Apoe in males. We recently found that Apoe expression is downregulated in microglia during development.29 In the present study, we found that the majority of microglial specific genes were downregulated prior to disease onset concomitant with increased Apoe expression. Treatment of adult microglia with APOE suppressed the M0 microglia signature and induced a M1-like phenotype. Genetic ablation of miR-155 restored the expression of microglial genes and attenuated expression of Apoe in the spinal cord of SOD1 mice. These results demonstrate that the APOE pathway is a major pro-inflammatory mediator in microglia during disease progression in SOD1 mice and thus may also be a potential target of therapy in ALS.

It was recently reported by Chiu et al that resident microglia increase in the spinal cord during disease progression in SOD1 mice and that the microglia-specific gene Olfml3 increased >5-fold in whole SOD1G93A spinal cord. Chiu et al concluded that resident microglia increase in spinal cords during disease progression and monocytes do not.39 Although we are in agreement that Olfml3 is a microglial specific gene29 we did not find it increased in microglia in SOD1 mice. In fact, we found that all microglia specific transcriptional factors including Egr1, Atf3, Fos and Mafb were downregulated. In addition, upstream regulators related to microglia development and survival such as Tgfb1, Tgfbr1 and Csf1r were also downregulated. Consistent with this, we found that miR-155 is the most upregulated miRNA in microglia and spinal cord tissue of both SOD1G93A mice and ALS subjects. Previous studies showed that miR-155 directly targets Csf1r36 and Olfml360 and these genes along with the microglial signature were suppressed in spinal cord microglia. Of note, a recent study showed that targeting Csf1r ablate microglia.38 These findings are consistent with the decrease in microglia we observed. We also found downregulation of the TGFβ1 pathway in microglia from SOD1 mice. It has been shown that overexpression of miR-155 reduces TGFβ1 production by repression of SMAD221 and SMAD5.61 Moreover, using our novel anti-FCRLS mAb which specifically recognizes resident microglia29 in SOD1G93A/miR-155−/− mice we found decreased numbers of monocytes (CD11b+/FCRLS− cells) and increased numbers of microglia (CD11b+/FCRLS+ cells). Thus, genetic ablation of miR-155 both restored microglia and decreased recruited monocytes in the spinal cord of SOD1 mice.

Most subjects with ALS have the sporadic as apposed to familial forms linked to specific gene mutations. Nonetheless, the clinical characteristics of the sporadic and familial forms are similar. In our previous study, we found that the microRNA/gene signatures in peripheral monocytes from sALS and fALS patients were similar. In the current study, we found that miR-155 was the top upregulated microRNA in the spinal cord tissue from both sALS and fALS donors. Thus treatment with anti-miR-155 would be relevant to both groups of patients.

Our findings identify a new direction for the treatment of ALS by targeting the innate immune system. It is not known whether peripheral vs. intrathecal treatment with anti-miR-155 would be most beneficial, though fewer side effects would be expected with intrathecal delivery. It should be emphasized that although we found biologic effects with both peripheral and intraventricular administration of anti-miR-155, systemic treatment given 5 times resulted in greater survival as compared to one intraventricular treatment whereas changes in microglia were observed only with intraventricular treatment. Of note, genetic ablation of miR-155 reversed the pro-inflammatory signature of both peripheral Ly6CHi splenic monocytes and spinal cord FCRLS+ microglia. Thus our results cannot at this time identify the most effective route for treatment of ALS patients with anti-miR-155, both because different compartments are affected and because we did not test multiple intraventricular treatments. It is possible that targeting both compartments may be most effective. The identification of a unique inflammatory signature for blood monocytes in ALS patients8 provides a biomarker that could be used to monitor the effect of anti-miR-155 treatment given peripherally and measurement of CSF biomarkers such as apolipoproteins could be used to monitor the effect of anti-miR-155 treatment given into the nervous system.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Movie 1. SOD1G93A/miR-155−/− (left) and SOD1G93A/miR-155+/− (right) mice at the age of 145 days of age.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. J. Kipnis and Dr. N. Derecki (University of Virginia) for assistance with microglia phagocytosis assay, Ulricke Köck for performing immunohistochemical analysis, D. Kozoriz for the FACS sorting, and N. Kassam for support in antibody generation. This work was supported by the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Association (1V78RI and ALSA2087); a grant from the Department of Defense, ALS Research program (AL120029); the National Multiple Sclerosis Society fellowship and Junior Faculty award from the Nancy Davis Foundation for Multiple Sclerosis; the Edward N. & Della L. Thome Memorial Foundation; theNational Multiple Sclerosis Society (6002048) and the NIH (1R01NS088137 and R01AG043975). We thank Prize4Life, a non-profit organization dedicated to the discovery of treatments and a cure for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, for providing SOD1 mice.

Footnotes

Authorship

O.B. and H.L.W. conceived the study, designed experiments and wrote the paper. O.B., R.C., G.M., S.K., P.M.W., C.E.D., Z.F., D.J.G., O.K., R.E.F., A.K. and H.L. performed experiments. M.P.J. and S.P.G performed mass spectrometry experiments. N.P. performed RNAseq analysis. A.K. and R.E.F. performed neurons isolation. M.P.F., R.J.L., J.B. and M.E.C. provided human specimens and clinical data. All authors were participants in the discussion of results, determination conclusions and review of the manuscript.

Potential conflicts of interest

Brigham’s and Women Hospital has a patent on the use of miR-155 inhibitors as a therapy for ALS.

References

- 1.McGeer PL, McGeer EG. Inflammatory processes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 2002 Oct;26(4):459–70. doi: 10.1002/mus.10191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beers DR, Henkel JS, Zhao W, Wang J, Appel SH. CD4+ T cells support glial neuroprotection, slow disease progression, and modify glial morphology in an animal model of inherited ALS. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008 Oct 7;105(40):15558–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807419105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee R, Mosley RL, Reynolds AD, et al. Adaptive immune neuroprotection in G93A-SOD1 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mice. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(7):e2740. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiu IM, Phatnani H, Kuligowski M, et al. Activation of innate and humoral immunity in the peripheral nervous system of ALS transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Dec 8;106(49):20960–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911405106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beers DR, Henkel JS, Xiao Q, et al. Wild-type microglia extend survival in PU.1 knockout mice with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006 Oct 24;103(43):16021–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607423103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henkel JS, Engelhardt JI, Siklos L, et al. Presence of dendritic cells, MCP-1, and activated microglia/macrophages in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis spinal cord tissue. Ann Neurol. 2004 Feb;55(2):221–35. doi: 10.1002/ana.10805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lincecum JM, Vieira FG, Wang MZ, et al. From transcriptome analysis to therapeutic anti-CD40L treatment in the SOD1 model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature genetics. 2010 May;42(5):392–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butovsky O, Siddiqui S, Gabriely G, et al. Modulating inflammatory monocytes with a unique microRNA gene signature ameliorates murine ALS. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2012 Sep 4;122(9):3063–87. doi: 10.1172/JCI62636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mizwicki MT, Fiala M, Magpantay L, et al. Tocilizumab attenuates inflammation in ALS patients through inhibition of IL6 receptor signaling. Am J Neurodegener Dis. 2012;1(3):305–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swarup V, Phaneuf D, Dupre N, et al. Deregulation of TDP-43 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis triggers nuclear factor kappaB-mediated pathogenic pathways. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2011 Nov 21;208(12):2429–47. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boillee S, Yamanaka K, Lobsiger CS, et al. Onset and progression in inherited ALS determined by motor neurons and microglia. Science. 2006 Jun 2;312(5778):1389–92. doi: 10.1126/science.1123511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagai M, Re DB, Nagata T, et al. Astrocytes expressing ALS-linked mutated SOD1 release factors selectively toxic to motor neurons. Nature neuroscience. 2007 May;10(5):615–22. doi: 10.1038/nn1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobayashi K, Imagama S, Ohgomori T, et al. Minocycline selectively inhibits M1 polarization of microglia. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e525. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liao B, Zhao W, Beers DR, Henkel JS, Appel SH. Transformation from a neuroprotective to a neurotoxic microglial phenotype in a mouse model of ALS. Exp Neurol. 2012 Sep;237(1):147–52. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]