Abstract

Despite the myriad of different sensory domains encoded in bacteria, only a few types are known to control the cell cycle. Here we use a forward genetic screen for Caulobacter crescentus motility mutants to identify a conserved single-domain PAS (Per-Arnt-Sim) protein (MopJ) with pleiotropic regulatory functions. MopJ promotes re-accumulation of the master cell cycle regulator CtrA after its proteolytic destruction is triggered by the DivJ kinase at the G1-S transition. MopJ and CtrA syntheses are coordinately induced in S-phase, followed by the sequestration of MopJ to cell poles in Caulobacter. Polarization requires Caulobacter DivJ and the PopZ polar organizer. MopJ interacts with DivJ and influences the localization and activity of downstream cell cycle effectors. Because MopJ abundance is upregulated in stationary phase and by the alarmone (p)ppGpp, conserved systemic signals acting on the cell cycle and growth phase control are genetically integrated through this conserved single PAS-domain protein.

The bacterium Caulobacter crescentus is a model organism for research on the bacterial cell cycle and cell division processes. Here, Sanselicio et al. show that the MopJ protein contributes to the control of cell cycle and growth in C. crescentus.

The bacterium Caulobacter crescentus is a model organism for research on the bacterial cell cycle and cell division processes. Here, Sanselicio et al. show that the MopJ protein contributes to the control of cell cycle and growth in C. crescentus.

Cellular motility is responsive to external signals such as nutritional changes, but it is also regulated by cues induced systemically during each cell division cycle1,2. This latter characteristic has been successfully exploited in motility screens to uncover cell cycle regulators in the model bacterium Caulobacter crescentus (herein Caulobacter), an aquatic α-Proteobacterium that is easily synchronized by density-gradient centrifugation owing to a cell cycle-regulated capsule3,4,5,6. Motility is conferred by the polar flagellum, a structure that is required for the dispersal of the swarmer cell type. Caulobacter divides asymmetrically into a swarmer cell that resides in a G1-like quiescent state and harbours the flagellum and several pili at the same cell pole, and a replicative (S-phase) cell whose old cell pole is decorated by a cylindrical extension of the cell envelope (the stalk) tipped by an adhesive holdfast (Fig. 1a)2. Flagellar motility along with adhesive properties (conferred by the polar pili and holdfast) and cell division are wired into the C. crescentus cell cycle circuitry at the transcriptional level by the master cell cycle regulator CtrA7, a DNA-binding response regulator (RR) of the OmpR family4 whose synthesis is activated in S-phase by the transcriptional regulator GcrA8. Following its synthesis, CtrA activates many developmentally regulated promoters, including those of motility, pilus, holdfast and cell division genes7,9,10,11. CtrA also functions as negative regulator of gene expression and, directly and/or indirectly, inhibits firing of the origin of DNA replication (Cori). Cori fires only once during the Caulobacter cell cycle and is bound by CtrA at multiple sites12,13.

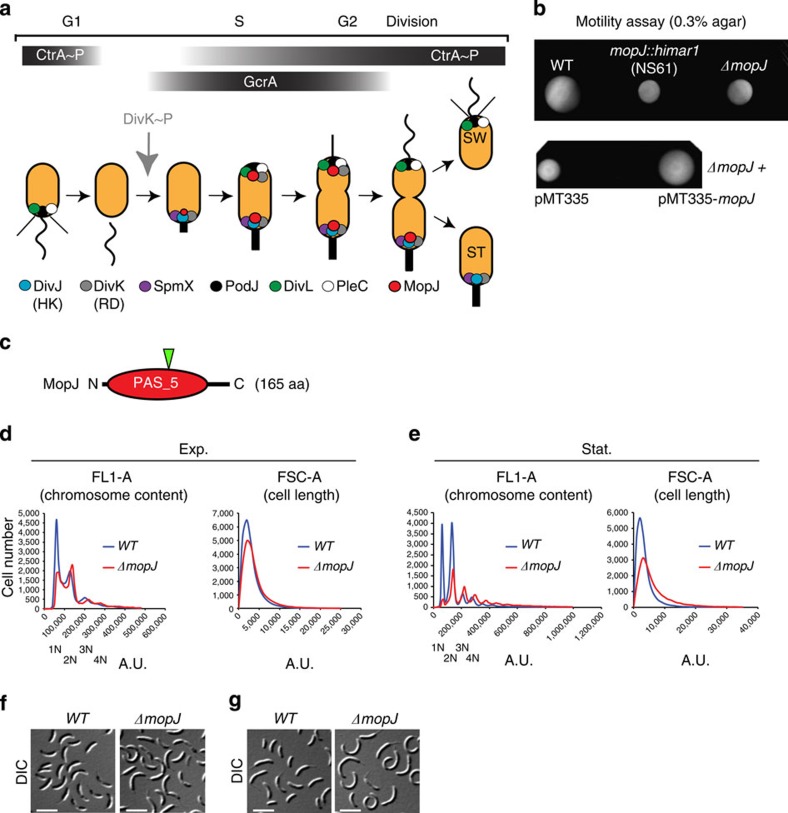

Figure 1. MopJ, a pleiotropic regulator controlling motility and cell cycle progression in Caulobacter crescentus.

(a) Model showing the localization of His-Asp signalling proteins and its regulators along with MopJ during Caulobacter crescentus cell cycle. The black bars show the abundance of the transcriptional regulators CtrA (and phosphorylated CtrA, CtrA∼P) and GcrA. The grey arrow indicates when phosphorylation of the DivK receiver domain (RD) by the DivJ histidine kinase (HK) commences. Phosphorylated DivK (DivK∼P) is present henceforth. The thin vertical line in black represents the flagellum before it rotates (wavy line). The thick vertical line in black represents the stalk. The thin slanted black lines represent the polar pili. (b) (Upper panel) Motility assay on swarm agar plate of WT, mopJ::himar and ΔmopJ cells. (Lower panel) complementation of ΔmopJ cells harbouring the empty vector pMT335 or pMT335-mopJ. (c) Scheme of domain organization of MopJ from N- to C-terminus indicated by the total amino-acid (aa) length. The green arrowhead points to the residue in the mopJ coding sequence that was disrupted by the himar1 transposon insertion. (d,e) FACS analysis of WT and ΔmopJ cells. Genome content (FL1-A channel) and cell size (FSC-A channel) were analysed by FACS during exponential (d, Exp.) and stationary (e, Stat.) phases in M2G. G1 (1 N) and G2 cell (2 N) peaks of fluorescence intensity are readily visible (particularly in Stat. phase cells) and are labelled accordingly. S-phase cells are reflected by the broad intermittent signal (absent in Stat. phase cells). (f,g) Differential interference contrast (DIC) images of WT and ΔmopJ cells during Exp. (f) and Stat. (g) phases in M2G.

The DNA-binding activity of RRs such as CtrA is regulated by phosphorylation at a conserved (Asp) residue, a step that is often executed directly by a histidine kinase (HK)7. Before the phosphate can be accepted by the RRs, the dimeric HK trans-auto-phosphorylates a conserved histidine (His) in an ATP-dependent manner. However, phosphorylation of RRs can also occur indirectly by way of two intermediary components in the His-Asp phosphorylation pathway, an Asp-containing receiver domain and a His-containing phosphor-transfer domain14. Complex regulatory schemes emerge when such multi-component His-Asp pathways are arranged in tandem15. The accumulation of phosphorylated CtrA (CtrA∼P) underlies such a complex His-Asp pathway topology15,16,17. CtrA∼P is present in G1-phase, degraded at the G1-S transition by the ClpXP protease18,19, to enable the initiation of DNA replication, and then re-synthesized and phosphorylated during S-phase (Fig. 1a). The removal of CtrA∼P at the G1-S transition is induced when the DivJ HK phosphorylates its substrate, the DivK receiver domain, which downregulates both the phosphorylation and half-life of CtrA via the DivL tyrosine kinase15,16,20,21,22,23,24. CtrA abundance and stability are also regulated by the conserved alarmone (p)ppGpp, which tunes cell cycle progression in response to nutritional signals25,26,27,28,29.

Superimposed on the temporal events is the spatial regulation of these His-Asp pathway components (Fig. 1a)30. At the G1-S transition, DivJ is recruited to the stalked pole by its localization factor SpmX, an event that also is required for optimal DivJ kinase activity in vivo3,31,32. DivK is enriched at the poles as well, enhancing kinase activity33, but a significant fraction of DivK is also dispersed17,34. DivK activity is antagonized by the phosphatase PleC that is recruited to the pole opposite the stalk by its localization factor PodJ32,35,36,37. A pleiotropic effector of protein polarization in C. crescentus is the polar organizing protein Z that is thought to self-assemble into a polar matrix at both cell poles to sequester proteins like SpmX, DivJ, DivK and others38,39,40,41. Although the DivJ and SpmX complex is unipolar, DivK localization is bipolar and promoted by SpmX and DivJ activity17,38, indicating that DivK localization opposite the stalk is regulated by another factor. The sequestration of DivK to the stalked pole is governed by DivJ, even in the absence of kinase activity17.

Here, we report a screen for motility mutants that unearthed a conserved and cell cycle-regulated single-domain PAS (Per-Arnt-Sim)42 protein (MopJ) that promotes CtrA accumulation during exponential growth and in stationary phase. MopJ is localized to the cell poles where it acts on downstream cell cycle signalling proteins, whereas upstream cell cycle regulators promote MopJ polarization. Our work unveils MopJ as a modulator of the spatio-temporal circuitry controlling bacterial cell cycle progression and as a regulatory node through which stationary phase and (p)ppGpp-dependent nutritional signals are integrated.

Results

MopJ is a pleiotropic regulator of motility

Our previous comprehensive transposon mutagenesis screen for strains with a motility defect on swarm (0.3%) agar that led to the identification of the spmX gene3 also yielded one mutant strain (NS61, Fig. 1b) harbouring a himar1 insertion in the uncharacterized gene CCNA_00999 (at nucleotide position 1082252 of the Caulobacter crescentus wild-type (WT) strain NA1000 (ref. 43). This gene is predicted to encode a single-domain PAS protein (PAS_5, pfam07310, residues 15–147, Fig. 1c) that is 165 residues in length and is henceforth referred to as MopJ (motility PAS domain associated with DivJ, see below). The PAS domain, a five-stranded antiparallel β-sheet flanked by several α-helices, is generally used to bind small-molecule ligands and is structurally related to the GAF regulatory (GMP-specific and -regulated cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase, Adenylyl cyclase and Escherichia coli transcription factor FhlA) domain often encoded on the same polypeptide42. Orthologues of MopJ are also encoded in the genomes of distantly related α-Proteobacteria (Supplementary Fig. 1) such as the animal pathogen Brucella melitensis (BMEI0738), the plant pathogen Agrobacterium tumefaciens (Atu1754) and the plant symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti (SMc01000). These proteins exhibit a similar domain organization with MopJ, that is, a single PAS_5 domain without any associated regulatory or effector domain (Fig. 1c). The himar1 transposon in NS61 lies near the middle of the mopJ gene (that is, after codon 89, Fig. 1c), presumably disrupting its function. In support of this notion, an in-frame deletion of mopJ (ΔmopJ) in WT cells recapitulated the motility defect observed in the mopJ::himar1 mutant on soft agar (Fig. 1b). As the motility defect of ΔmopJ cells can be corrected by supplying mopJ in trans on a plasmid (pMT335-mopJ) under the control of the vanillate-inducible promoter Pvan (Supplementary Fig. 2a), we conclude that MopJ is a hitherto uncharacterized regulator of motility in C. crescentus.

As inactivation of cell cycle regulators often results in pleiotropic defects in C. crescentus including a reduction of motility5 caused by a change in the fraction of G1-phase cells in the population, we probed for such changes by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of exponentially growing WT and ΔmopJ cells stained with the nucleic acid dye SYTOX Green (Fig. 1d). A lower G1:G2 cell ratio was observed in ΔmopJ cultures compared with WT, while the number of S-phase cells seemed unaffected. By contrast, stationary WT or ΔmopJ cultures contained few S-phase cells, confirming that the majority of cells are no longer replicating (Fig. 1e). Although stationary WT cells have an equal tendency to arrest either in G1- or G2-phase, stationary ΔmopJ cells are enriched in G2-phase over G1-phase. Consistent with these findings, differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy and FACS revealed only slight increase in cell length caused by the ΔmopJ mutation in exponential phase (Fig. 1d,f), whereas in stationary phase many ΔmopJ cells are elongated and appear to divide aberrantly (Fig. 1e,g).

Taken together, our results reveal MopJ as a novel pleiotropic regulator of motility and of normal cell cycle progression in C. crescentus. Specifically, MopJ promotes the accumulation of G1-phase cells in exponential phase and of G1- and G2-phase cells in stationary phase.

MopJ acts on the CtrA regulon and is induced by (p)ppGpp

Knowing that MopJ impacts both motility and the abundance of G1 cells, we tested if MopJ affects the expression of the CtrA regulon, as this includes motility, division and G1-phase genes9,10,12. In addition, this master transcriptional regulator is a likely target of MopJ because it also regulates the initiation of chromosome replication4,12. To this end, we measured if β-galactosidase (LacZ) expression from CrA-regulated promoters is altered in exponential and stationary phase WT and ΔmopJ cells harbouring PpilA-, PsciP- or PfljM-lacZ promoter probe plasmids (harbouring LacZ under the control of the promoter of the pilA pilin gene, the sciP repressor gene or the fljM minor flagellin gene, Fig. 2a,b) that are directly activated by CtrA9,10,44 versus a podJ promoter reporter (Supplementary Fig. 3A) that is repressed by CtrA. Although only a modest reduction in LacZ activity (14–25%, depending on the CtrA-activated promoter, see Supplementary Table 1) was discernible in exponentially growing ΔmopJ cells compared with WT cells (Fig. 2a), this difference was accentuated in stationary phase (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 1) and even further magnified in a reporter that is indirectly activated by CtrA such as PfljK-lacZ, in which the promoter of the major flagellin gene fljK drives LacZ expression (Fig. 2a,b and Supplementary Table 1). PfljK is a target of the FlbD activator whose expression in turn is directly and positively regulated by CtrA9,10.

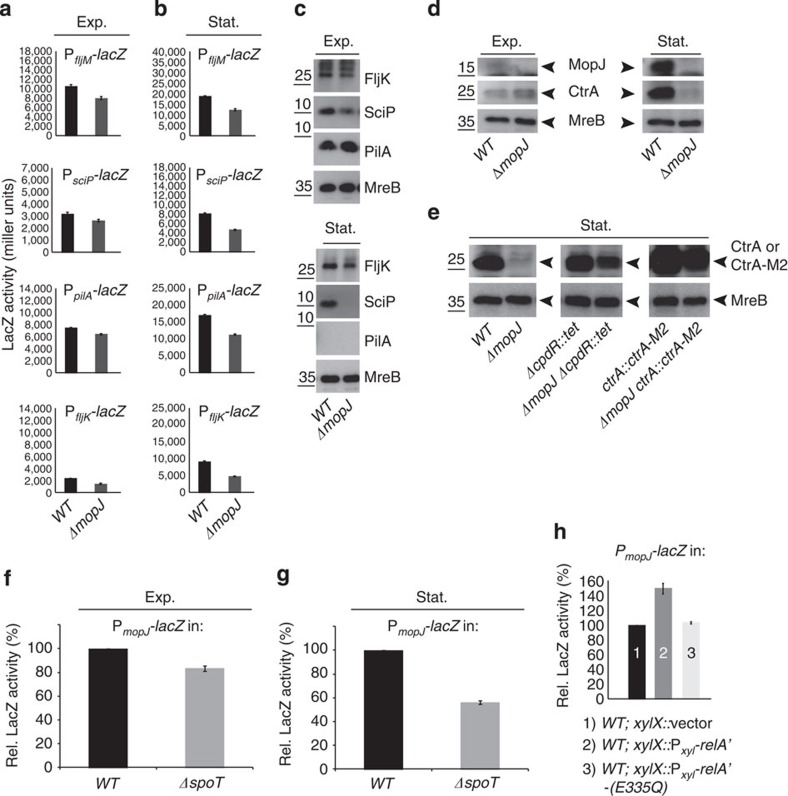

Figure 2. MopJ promotes CtrA accumulation and is regulated by (p)ppGpp.

(a,b) Promoter-probe assays of transcriptional reporters carrying the fljM, sciP, pilA or fljK promoter fused to a promoterless lacZ gene in WT and ΔmopJ cells in exponential (a, Exp.) and stationary (b, Stat.) phase. The graphs show lacZ-encoded β-galactosidase activities measured in Miller Units. (c) Immunoblot showing the steady-state levels of the major flagellin FljK, the SciP-negative regulator and the PilA structural subunit of the pilus filament in WT and ΔmopJ cells in Exp. and Stat. phase. The steady-state levels of the MreB actin are shown as a loading control (see Supplementary Fig. 4A). (d) Immunoblots showing CtrA and MopJ abundance in Exp. and Stat. phase ΔmopJ versus WT cells. Steady-state levels of MreB are shown as loading control (see Supplementary Fig. 4B). (e) Accumulation of CtrA is increased in ΔmopJ cells during Stat. phase either by inactivation of a proteolytic regulator encoded by cpdR (ΔcpdR::tet) or by appending an M2 (FLAG) epitope to the C-terminus of CtrA (ctrA::ctrA-M2). Immunoblot showing the steady-state levels of CtrA in WT, ΔmopJ, ΔcpdR::tet and ΔmopJ ΔcpdR::tet cells and the levels of CtrA-M2 in ctrA::ctrA-M2 and ΔmopJ ctrA::ctrA-M2 cells. Steady-state levels of MreB are shown as loading control. (f,g) Promoter-probe assays of transcriptional reporters carrying the PmopJ-lacZ in WT and ΔspoT cells in Exp. (f) and Stat. (g) phase. (h) LacZ assays with PmopJ-lacZ promoter-probe plasmid in WT and cells expressing the constitutive active form of E. coli RelA (RelA') and the catalytic mutant (RelA'-E335Q) fused to the FLAG tag in the presence of xylose. (a,b,f,g,h) Error bar (black bar) is shown as standard deviation (s.d., n=3).

Immunoblotting using polyclonal antibodies to FljK, SciP and PilA confirmed the trends observed with the LacZ transcriptional reporters (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 4a). (Note that the PilA protein is absent from stationary phase WT cells for reasons that are currently unknown, but is likely operating at the post-transcriptional level (compare Fig. 2b,c and Supplementary Fig. 4a). Immunoblotting using antibodies to CtrA revealed that CtrA abundance is strongly dependent on MopJ in stationary phase (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 4b), consistent with the exacerbated effects on CtrA and its regulon in stationary ΔmopJ cells compared with WT cells. Stabilizing CtrA either by masking the C-terminal recognition motifs for ClpXP in CtrA (using the ctrA::ctrA-M2 allele45) or by inactivating the gene encoding the CpdR proteolytic activator of CtrA16,20 restores CtrA abundance to near WT levels (Fig. 2e), indicating that CtrA proteolysis by the ClpXP protease contributes to downregulation of CtrA levels in stationary ΔmopJ cells.

Next, we raised antibodies to MopJ to probe for commensurate changes in MopJ abundance in stationary phase versus exponential phase. In support of the stationary phase defects of ΔmopJ cells described above, we observed that MopJ was barely detectable in lysates from exponential phase cells, but is abundant in lysates from stationary phase cells (Fig. 2d and see Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 4b). As the alarmone (p)ppGpp accumulates in stationary phase when nutrients become exhausted in bacteria25,46, we asked if the stationary phase induction of MopJ requires the (p)ppGpp-synthase/hydrolase SpoT27,28,47. To resolve this question, we conducted β-galactosidase (LacZ) measurements in cells harbouring a transcriptional reporter, in which a promoterless lacZ gene is fused to the mopJ promoter (PmopJ-lacZ). Accordingly, we measured PmopJ-lacZ activity during exponential and stationary phase in the presence or absence of SpoT (that is, in WT and ΔspoT cells, respectively), observing a strong (50%) reduction of PmopJ-lacZ expression in stationary cells lacking SpoT (Fig. 2f,g). To demonstrate that (p)ppGpp induction is sufficient for the PmopJ-lacZ induction even in exponential phase cells, we induced (p)ppGpp synthesis in exponential phase cells using the constitutively active (p)ppGpp synthase RelA' from E. coli47 and detected a commensurate increase in PmopJ-lacZ activity (Fig. 2h). By contrast, no induction was observed upon induction of the catalytic mutant derivative RelA'-E335Q (Fig. 2h), demonstrating that (p)ppGpp is necessary and sufficient for induction of PmopJ-lacZ.

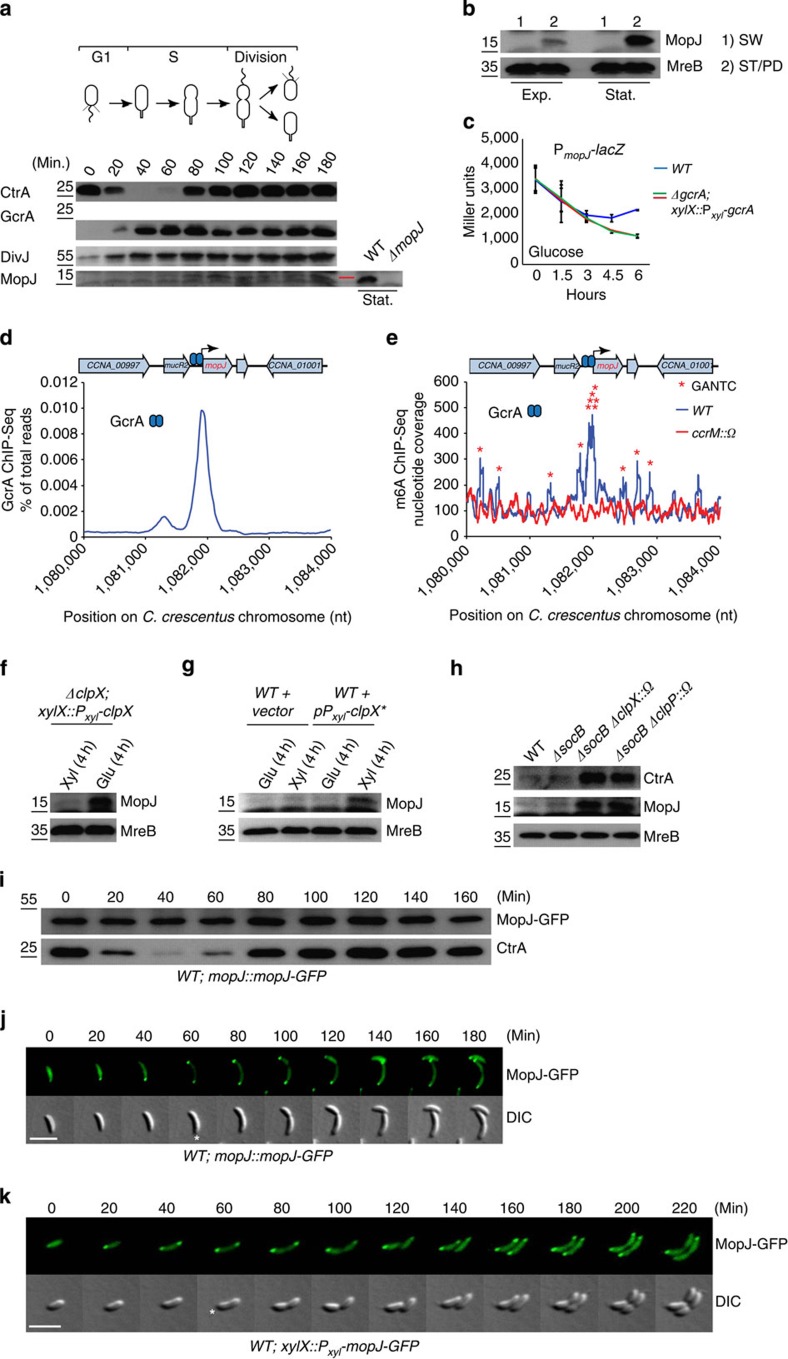

Figure 3. Multi-layered spatiotemporal regulation of MopJ.

(a) Immunoblots showing steady-state levels of MopJ, GcrA, CtrA and DivJ in synchronized WT cells and MopJ in stationary (Stat.) phase (a, right, see Supplementary Fig. 5a,b). The red line marks the position of MopJ. (b) MopJ levels in exponential (Exp.) or stationary (Stat.) phase swarmer (SW) and stalked (ST)/predivisional (PD) cells detected using antibodies to MopJ (see Supplementary Fig. 5c). (c) LacZ measurements (Miller units) of PmopJ-lacZ in WT (blue) and two independent ΔgcrA xylX::Pxyl-gcrA (red and green) mutants, during 6 h (hours) of inhibition (glucose) of gcrA expression. Note the decline in activity upon dilution of overnight cells is due to the prior induction in stationary phase by (p)ppGpp (see Fig. 2f–h and Supplementary Fig. 3b). Error bar (black bar) is shown as s.d. (n=3). (d) Occupancy of GcrA (blue ovals) at the mopJ locus in WT cells as determined by chromatin immunoprecipitation coupled to deep-sequencing (ChIP-Seq) using polyclonal antibodies to GcrA50. Occupancy is shown as percentage of total reads in the precipitated sample as a function of the chromosome coordinates. (e) Trace of N6-methyladenosine (m6A) marked DNA at mopJ locus in WT cells (blue trace) and ΔccrM::Ω (red trace) from ChIP-Seq experiment performed with antibodies to m6A50. Occupancy is shown as percentage of total nucleotide coverage in sequencing as a function of the chromosome coordinates at the mopJ locus. Stars show the positions of 5′-GANTC-3′ sequences that are methylated by the CcrM methyltransferase at the N6 position of adenine. (f–h) Immunoblots showing the steady-state levels of MopJ in ΔclpX xylX::Pxyl-clpX cells with (Xyl, xylose) or without (Glu, glucose) induction of Pxyl for 4 h (f), upon induction of the dominant negative form ClpX* from Pxyl for 4 h (g), and in WT, ΔsocB and ΔsocBΔclpX::Ω, ΔsocBΔclpP::Ω double mutants (h) along with CtrA and MreB (control). (i) Immunoblot showing MopJ-GFP and CtrA levels in synchronized mopJ::mopJ-GFP cells (see Supplementary Fig. 5d). (j,k) Time-lapse fluorescence imaging of live mopJ::mopJ-GFP cells (j) or WT xylX::Pxyl-mopJ-GFP cells (k). White asterisk denotes stalked pole. (a,i,j,k) Numbers indicate minutes after synchronization.

Thus, MopJ acts on CtrA and its regulon, especially in stationary phase, and (p)ppGpp signalling by SpoT induces MopJ at the transcriptional level in stationary phase cells.

Coordinated synthesis of MopJ and CtrA in S-phase

The functional relationship between MopJ and CtrA is further reinforced by their concurrent accumulation during the cell cycle, coordinated by the S-phase regulator GcrA. Immunoblotting revealed that MopJ appears during the cell cycle coincident with or slightly ahead of CtrA and follows the accumulation of GcrA and DivJ (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 5a,b). Separation of exponential and stationary phase WT cells into swarmer (G1-phase) and stalked/pre-divisional (S-phase) cell fractions showed MopJ to be absent from the former and present in the latter (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 5c). The MopJ expression pattern matches that of the TipF flagellar regulator, an unstable protein that is expressed from a GcrA-activated promoter in early S-phase and is subsequently proteolysed in a manner that depends on the ClpXP protease48. Measuring LacZ activity in GcrA-depleted cells harbouring the PmopJ-lacZ reporter, we observed a strong reduction after 6 h of depletion relative to WT (Fig. 3c) or to GcrA-replete cells (Supplementary Fig. 3b), indicating that GcrA also acts positively on this promoter. In support of this, previous chromatin immunoprecipitation coupled to deep-sequencing experiments revealed that GcrA binds PmopJ (Fig. 3d) efficiently in vivo and that it harbours N6-methyladenosine (m6A, Fig. 3e) marks, a hallmark of a class of promoters that fire in S-phase and that require methylation for efficient activation and binding of GcrA in vitro and in vivo49,50.

Interestingly, MopJ features two terminal alanine residues that resemble (class I) C-terminal recognition motifs of the ClpXP protease51 and MopJ was previously found associated with the ClpP protease in pull-down assays52. We therefore investigated if ClpXP regulates MopJ abundance in vivo. To this end, we used immunoblotting to monitor the abundance of MopJ in cells from which the ClpX ATPase component of the ClpXP proteolytic machine had been depleted (Fig. 3f) or in cells intoxicated with a dominant negative version of ClpX (Fig. 3g)53. We found steady-state levels of MopJ to be elevated under these conditions. Moreover, the abundance of MopJ and CtrA, a known ClpXP substrate18, is elevated upon disruption of the clpX or the clpP gene in ΔsocB mutant cells (Fig. 3h). (Note that inactivation of clpX or clpP is lethal in WT cells, but no longer in ΔsocB cells, in which the gene encoding the SocB toxin has been deleted54). Finally, the levels of a MopJ variant harbouring GFP fused to the C-terminus (MopJ-GFP) expressed from PmopJ no longer fluctuate during the cell cycle (Fig. 3I and Supplementary Fig. 5d) and confers motility to a comparable level as the untagged (WT) version (Supplementary Fig. 2b).

In sum, a combination of GcrA-controlled synthesis and ClpXP-dependent proteolysis restricts MopJ accumulation to S-phase and ensures that re-synthesis of CtrA and its reinforcement factor MopJ (see above) is linked, thus optimally reinforcing CtrA accumulation and function. Moreover, as MopJ is also induced in stationary phase by (p)ppGpp, an adaptive (nutritional) feed exists into the cell cycle.

Bipolar localization of MopJ requires the DivJ kinase

Superimposed on the temporal regulation of MopJ is its cell cycle-controlled polar sequestration revealed in time-lapse fluorescence microscopic imaging of live mopJ::mopJ-GFP cells (Fig. 3j). Although diffuse fluorescence was observed in G1-phase (swarmer) cells, MopJ-GFP localizes first to the stalked pole during the transition into S-phase (stalked) cells and adopted a bipolar localization until MopJ-GFP dispersed from the opposite pole at the time of cell division (Fig. 3j). MopJ-GFP localized in a similar way when expressed constitutively from the xylose-inducible Pxyl promoter (Fig. 3k), compared with expression from its native promoter in S-phase, providing further evidence that the cell cycle-regulated localization occurs even when MopJ is expressed ectopically. Imaging of MopJ-GFP (Fig. 4a) or GFP-MopJ (Supplementary Fig. 6) expressed from the xylX locus in unsynchronized C. crescentus cultures also revealed monopolar and bipolar localization patterns. Consistent with the time-lapse imaging, MopJ-GFP is bipolar in pre-divisional cells, but is dispersed from the pole opposite the stalk in deeply constricted cells (Figs 3j,k and 4a), a characteristic also observed for the DivK RR that is phosphorylated by the DivJ kinase (Fig. 1a). Further reinforcing the parallels between MopJ and DivK (bi)polarity, we observed that MopJ-YFP and DivK-CFP co-localize in C. crescentus WT cells (Fig. 4b). This prompted us to explore if MopJ and DivK rely on a common localization mechanism. Indeed, in the absence of DivJ, DivK-GFP delocalized34 (Fig. 4c) and MopJ-GFP as well (Fig. 4a,d and Supplementary Fig. 7a,b). Moreover, a truncated version (residues 1–392) of DivJ containing the HisKA domain, but lacking the ATPase (HATPase_c) domain, is sufficient to direct MopJ-GFP and DivK-GFP to the stalked pole, but no longer to the opposite pole (Fig. 4c,d and Supplementary Fig. 7a,b). Thus, as was reported for DivK-GFP previously, MopJ-GFP requires DivJ kinase activity to be sequestered to the pole opposite the stalk, but its sequestration to the stalked pole occurs independently of kinase activity17 (Fig. 4c,d). A further truncated version of DivJ (residues 1–329) no longer supported polar localization of MopJ-GFP and DivK-GFP (Fig. 4c,d and Supplementary Fig. 7a,b), indicating that the dimerization/phosphor-acceptor (HisKA) domain and/or a determinant encoded from residues 329 to 392 is critical to recruit MopJ and DivK to the stalked pole. By contrast, expression of full-length DivJ from a comparable plasmid reinstated bipolarity upon MopJ-GFP and DivK-GFP (Fig. 4c,d and Supplementary Fig. 7a,b). As both derivatives of DivJ can still localize to the stalked pole (albeit 50% less efficient for the shorter version, Supplementary Fig. 8), this experiment confirms that residues 329–392 of DivJ encode for the localization determinants of MopJ and DivK. We conclude that DivJ integrates the bipolar localization of two dissimilar effectors, MopJ and DivK, to the stalked pole and, in early pre-divisional cells, also to the opposite pole.

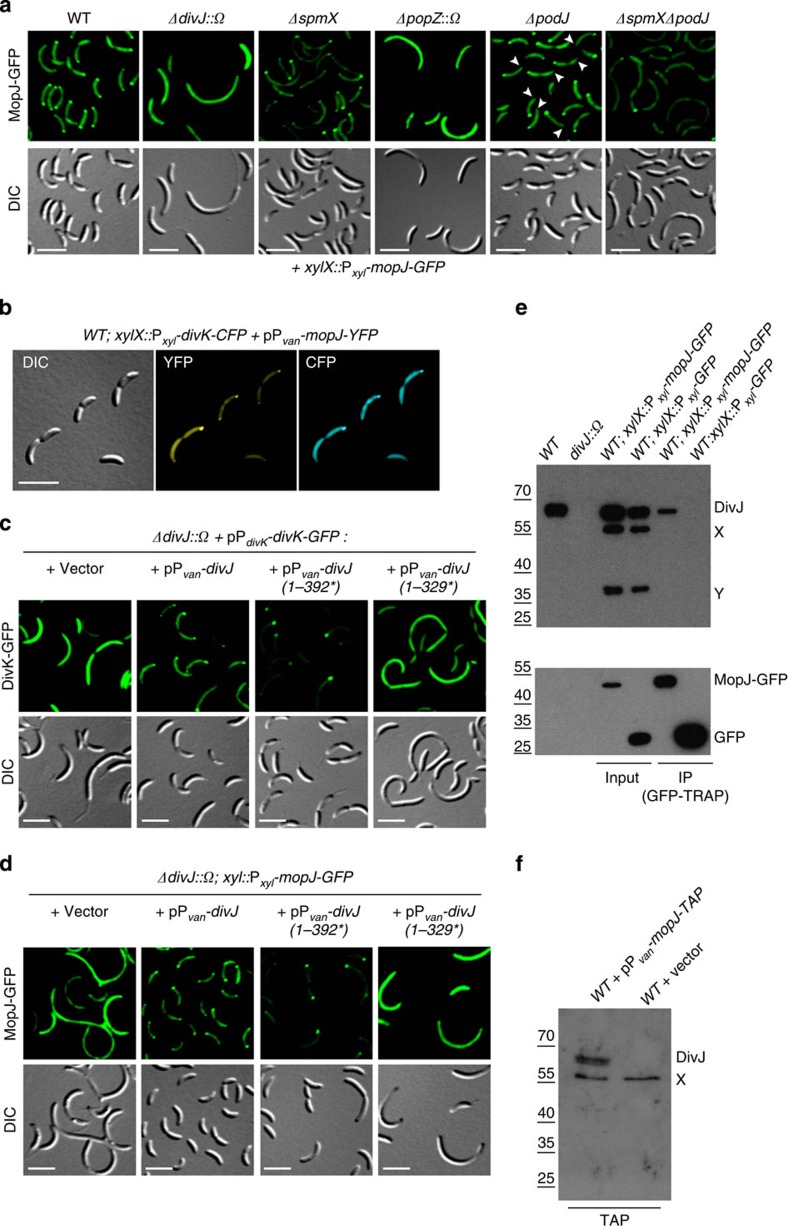

Figure 4. Polar localization of MopJ requires the DivJ kinase and the PopZ polar scaffold.

(a) Fluorescence and DIC images of live C. crescentus WT, ΔdivJ::Ω, ΔspmX, ΔpopZ::Ω, ΔpodJ or ΔpodJΔspmX cells expressing MopJ-GFP under the control of xylose promoter (Pxyl) at the xylX locus. White arrowheads point to the flagellated pole. (b) Co-localization of DivK-CFP expressed from Pxyl at the xylX locus in WT cells and MopJ-YFP expressed from Pvan on pMT374. The corresponding DIC image is also shown. (c) Fluorescence and DIC images of ΔdivJ::Ω cells expressing DivK-GFP fusion from pMR10-divK-GFP and various versions of DivJ, including full-length DivJ, DivJ-392 (short version of divJ encoding a truncated protein without histidine kinase domain) or DivJ-329 (short version of divJ encoding a truncated protein without kinase and dimerization domains) under the control of the vanillate promoter (Pvan) from pMT335. The control harbouring the empty vector is also shown. (d) Fluorescence and DIC images of ΔdivJ::Ω cells expressing MopJ-GFP under the control of Pxyl and the different forms of DivJ from pMT335 as described in c. (e) Co-immunoprecipitation (IP) of DivJ with MopJ-GFP from a GFP-TRAP affinity matrix (ChromoTek GmbH). Precipitated samples were probed for the presence of DivJ and GFP by immunoblotting using antibodies to DivJ (upper) and GFP (lower). Cell lysates used as input are also shown. (f) Tandem-affinity-purification (TAP) of MopJ-TAP from Pvan on pMT335 followed by immunoblotting of the samples for the presence of DivJ using polyclonal antibodies to DivJ. In e and f, X and Y denote nonspecific proteins that react with the antiserum or degradation products.

In support of the notion that a physical interaction between MopJ and DivJ underlies the localization of MopJ to the stalked pole, co-immunoprecipitation experiments revealed that DivJ is pulled-down with MopJ-GFP from cellular lysates of a WT strain expressing MopJ-GFP from Pxyl (Fig. 4e). By contrast, DivJ was not detectable in comparable pull-downs from lysates of the WT strain expressing GFP from Pxyl (Fig. 4e). Furthermore, DivJ was also recovered with MopJ in tandem-affinity purification experiments55 conducted with lysates of WT cells expressing MopJ-TAP from Pvan (Fig. 4f). Having shown that MopJ resides in a complex with DivJ, we then tested whether overexpression of MopJ can affect the DivJ-regulated subcellular distribution of the other DivJ-interacting effector DivK17,34 (Fig. 5a,b). Live-cell imaging of DivK-GFP in cells overexpressing MopJ from Pvan revealed an enhancement of DivK-GFP polar localization and a concomitant reduction of the cytoplasmic fluorescence that correlated with the strong induction of MopJ upon the addition of vanillate (Fig. 5a,b), without affecting DivK∼P levels noticeably by in vivo phosphorylation analysis (Fig. 5c). However, we found that ΔmopJ cells are sensitized towards elevated DivK levels from a plasmid expressing DivK under the control of Pxyl, suggesting that extra DivK17 further curbs the CtrA pathway in ΔmopJ cells (in which activation of the CtrA regulon is already disturbed, see above) to inhibit growth (Fig. 5d) and division (Fig. 5e) more than in WT cells. Taken together, these experiments show that MopJ binds DivJ and depends on it for its own polar localization, while promoting the polar sequestration of DivK and attenuating its activity.

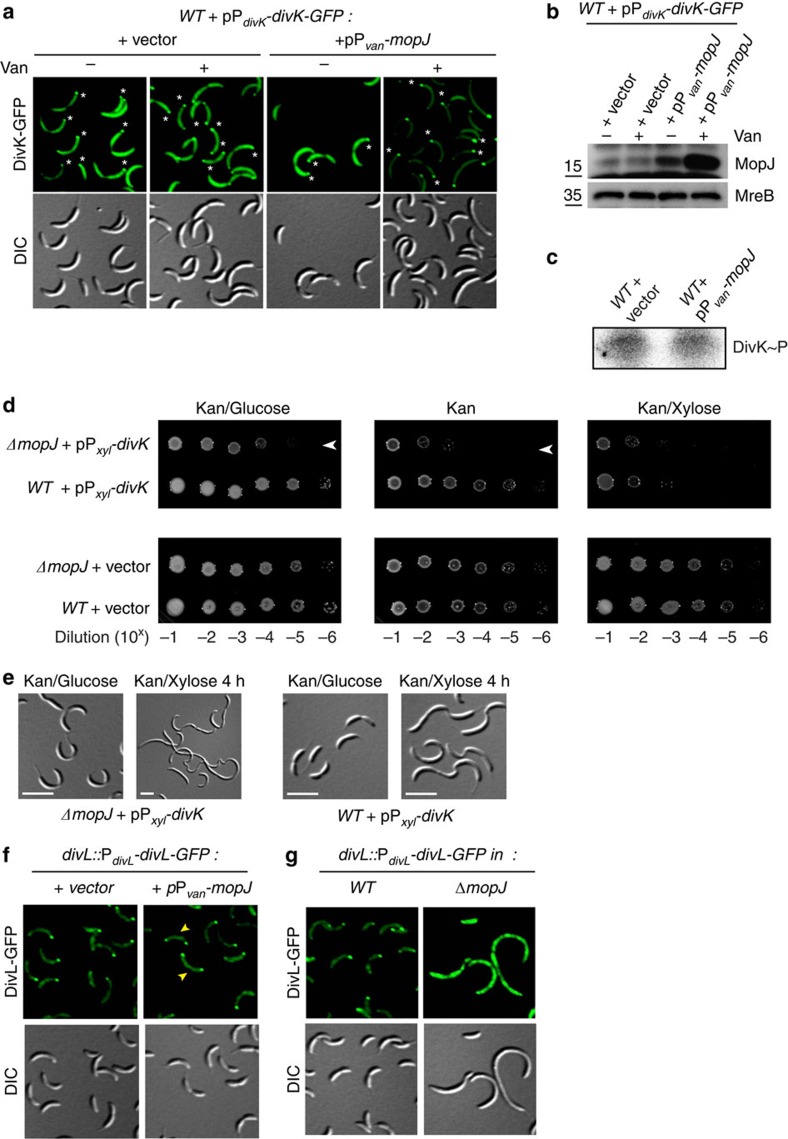

Figure 5. MopJ affects DivK localization and function.

(a) Fluorescence and DIC imaging of WT cells harbouring pMR10-divK-GFP and pMT335-Pvan-mopJ with (+) or without (−) induction (50 μM of vanillate) of MopJ from Pvan on pMT335. The controls harbouring pMR10-divK-GFP and the empty vector (pMT335) are also shown. The position of stalks are indicated by a white asterisk. (b) Immunoblot showing the steady-state levels of MopJ in strains used in a. Steady-state levels of MreB are shown as a loading control. (c) In vivo phosphorylation of cultures with 32P followed by immunoprecipitation reveals DivK∼P levels in WT cells harbouring pMT335 or pMT335-mopJ (Pvan-mopJ) after with vanillate (50 μM). (d) Effect of ΔmopJ mutation on viability in the presence of extra DivK. Efficiency of plating assays of WT and ΔmopJ cells harbouring the empty vector (pMR10) or the Pxyl-divK expression plasmid (pMR10-Pxyl-divK). Serial tenfold dilutions of cells plated on PYE agar with kanamycin and glucose (kan+gluc, glucose represses Pxyl), kanamycin (kan, background expression from Pxyl) and kanamycin and xylose (kan+xyl, xylose induces Pxyl) agar. (e) DIC (differential interference contrast) imaging of cells described in d in glucose or 4 h after induction with xylose (0.3%). The medium was supplemented with kanamycin (5 μg ml−1). (f) Effect of MopJ overexpression on DivL-GFP localization. The empty vector (pMT335) or the Pvan-mopJ plasmid (pMT335-mopJ) was transformed into divL::PdivL-divL-GFP cells and the resulting cells imaged by DIC and fluorescence microscopy 4 h after induction with vanillate (50 μM). Yellow arrowheads point to cells with bipolar DivL-GFP. (g) Effect of mopJ deletion on DivL-GFP localization. The divL::PdivL-divL-GFP allele was transduced in WT and ΔmopJ cells and the resulting cells imaged by DIC and fluorescence microscopy.

Examining possible effects on downstream components, we found that MopJ overexpression not only alters the subcellular distribution of DivK, but also that of its interaction partner, the tyrosine kinase DivL24 that localizes primarily to the pole opposite the stalk15,22,56 (Fig. 1a). Overexpression of MopJ caused a near fivefold increase in the fraction of bipolar DivL-GFP (expressed from the native promoter at the divL locus in lieu of endogenous DivL; Fig. 5f and Supplementary Fig. 9). Conversely, in cells lacking MopJ, DivL-GFP was largely delocalized (Fig. 5g) and a divL::Tn5 mutation (in which Tn5 is inserted upstream of the region encoding the HisKA domain) did not impact MopJ-GFP localization (Supplementary Fig. 10). The previous observation that DivL is delocalized in the absence of DivJ56 is consistent with our findings, as we showed above that DivJ is also required for the polarization of MopJ-GFP. Intriguingly, DivL localization is thought to be dependent on the onset of DNA replication57. The result that MopJ is required for DivL localization and MopJ expression requires GcrA is noteworthy, as it could provide an explanation for the finding that DivL polarization (and the concomitant re-accumulation of CtrA that this event regulates) requires S-phase entry57. GcrA expression and S-phase entry are known to be dependent on the replication initiator DnaA58.

In sum, MopJ is both target (via DivJ) and effector (via DivK and DivL) of the Caulobacter spatiotemporal cell cycle network and is thus perfectly positioned to reinforce CtrA with the synthesis of both proteins in S-phase and is genetically linked as expression of both proteins is directly induced by GcrA.

A second localization pathway controls polarization of MopJ

Although DivJ is necessary for the bipolar localization of MopJ, two findings indicate that it is not sufficient for bipolarity. First, MopJ is localized to the pole opposite the stalk (Fig. 4a), where no focus of DivJ is observed32. Second, MopJ is still polarized when DivJ is delocalized by inactivation of its localization factor SpmX (that is, in ΔspmX mutant cells, Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 11)3. Taken together, this indicates that other factors must promote polarization of MopJ. As it is also conceivable that DivJ simply targets MopJ to the membrane or fastens it there, we also explored whether the bipolar scaffolding protein PopZ that forms adhesive patches at both cell poles26,36,38,39,40 might keep MopJ-GFP polarized. Live-cell imaging revealed that MopJ-GFP is dispersed in ΔpopZ::Ω mutant cells (Fig. 4a). As PopZ has also been likened to a molecular plug that prevents diffusion away from the cell pole, we predicted that an additional factor promotes MopJ-GFP localization to the pole opposite the stalk. The PodJ polarity protein is known to attract regulatory proteins of CtrA to the pole opposite the stalk36,37,59,60. We observed MopJ-GFP to be monopolar in ΔpodJ mutant cells, unable to assemble into foci at the pole opposite the stalk regardless of whether SpmX was present or not (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 11). This dependence of MopJ-GFP on PodJ for localization to the flagellated pole not only supports the existence of distinct recruitment mechanisms of MopJ-GFP for each cell pole in WT cells, but also provides an explanation of why DivL is no longer localized to the flagellated pole in ΔpodJ cells59. It also points to a possible explanation of how DivJ might influence MopJ localization to the pole opposite the stalk. As the expression of the gene encoding the PerP periplasmic protease that cleaves PodJ is strongly and directly upregulated by CtrA in ΔdivJ::Ω mutant cells9,10,61, we hypothesize that DivJ promotes the localization of MopJ at the pole opposite the stalk indirectly through PodJ (or another DivJ-dependent protein).

Discussion

A single-domain PAS protein, MopJ, is not only regulated by cell cycle cues, but also integrates nutritional and growth phase regulatory signals to exert topological control over conserved components of a bacterial cell cycle network (Fig. 6). The identification of MopJ enabled us to illuminate two important and hitherto enigmatic cell cycle events. The first conundrum was how the master regulator CtrA can re-accumulate in S-phase4, a time when DivK is still phosphorylated and signals the removal of CtrA30,34. Unless the proteolytic cascade is attenuated and/or the rate of synthesis is potentiated such that it exceeds proteolysis, CtrA accumulation should be suppressed or curbed. We found that the PAS-domain protein MopJ indeed enhances CtrA accumulation and acts on DivK and its target DivL15. MopJ re-accumulation is temporally linked with that of CtrA through the S-phase-specific transcriptional activator GcrA that binds the ctrAP1 and the mopJ promoter8,49,50, thus reinforcing CtrA re-synthesis with the coordinated synthesis of its enhancing factor MopJ in S-phase.

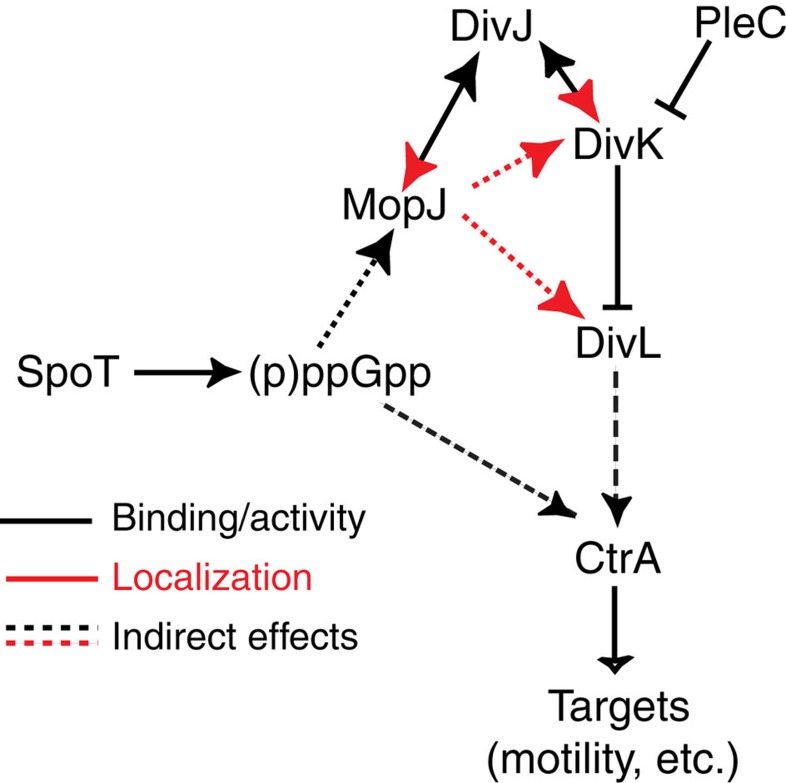

Figure 6. Proposed action of MopJ on the Caulobacter cell circuitry.

Summary scheme depicting the interactions of MopJ with the cell circuitry as determined in this work. Effects on protein localization are shown in red, whereas interactions shown in black designate direct interactions that generally result in activation (arrow, DivJ-DivK) or inhibition (T-bar, PleC-DivK, DivK-DivL). The scheme also shows the effects of the alarmone (p)ppGpp in inducing MopJ and the maintenance of CtrA25,26,28,47 (see Discussion).

By discovering that MopJ acts at the same subcellular site as the CtrA His-Asp phosphorelay components DivJ, DivK and DivL, we were able to identify MopJ as an important missing link connecting DivL polarization to DivJ (Fig. 6) and likely to the onset of DNA replication. MopJ polarization requires the polar organizer PopZ and the DivJ kinase. With the previous findings that polar localization of DivJ is itself dependent on PopZ assembly at polar sites38,40, our work extends this spatiotemporal regulatory network by showing that MopJ associates with DivJ (Fig. 4), enhances the sequestration of DivK to the cell poles (attenuating DivK function, Fig. 5), governs subcellular localization of DivL and facilitates CtrA accumulation and expression of its target promoters (Fig. 2).

The stationary phase and (p)ppGpp-based induction of MopJ unveils a concerted feed-forward mechanism underlying signal integration during bacterial cell cycle progression, acting on an essential master transcriptional regulator in different phases of growth (Fig. 6). Why MopJ abundance increases in stationary phase remains to be determined, but our experiments suggest that this inductions occurs at the transcriptional level as the activity of the mopJ promoter is elevated in stationary phase and is inducible in nutrient replete conditions when (p)ppGpp levels are raised artificially in exponential phase (Fig. 2). As (p)ppGpp signals nutrient starvation by globally reprogramming RNA polymerase and is induced in stationary phase in many bacteria46, the induction of MopJ is likely mediated at the level of promoter activity. It is also possible that MopJ synthesis is further reinforced at the level of protein stability by inhibiting ClpXP-mediated proteolysis (Fig. 3). It is not obvious why MopJ should be induced in stationary phase when nutrients are exhausted to enhance the cell cycle regulator CtrA. However, it is known that CtrA levels are maintained in the presence of (p)ppGpp26,28,47, and our results raise the possibility that this effect is (at least partially) mediated by (induced) MopJ. In light of the fact that the number of cells undergoing DNA replication is strongly diminished in stationary phase, with cells accumulating predominantly in G1 and G2 phase (Fig. 1), along with the fact that CtrA acts on replication control4,12, we suspect that CtrA is responsible or at least contributes to this replication arrest. In support of this, cells no longer exhibit a normal stationary phase arrest in the absence of MopJ (Fig. 1), and the abundance of CtrA is strongly reduced under these conditions (Fig. 2). Such stationary-phase-induced replication arrest may be further accentuated by other (p)ppGpp-dependent mechanisms, such as the reduction of the replication initiator DnaA, an unstable protein62,63, when (p)ppGpp levels are high26,28,47. It is also noteworthy that in contrast to this specific cell cycle control mechanism on the level of a master regulator, (p)ppGpp induces a general growth arrest and a state of antibiotic tolerance (known as persistence) in E. coli and likely other bacteria through a shutdown of macromolecular synthesis by type II toxin–antitoxin systems that are activated indirectly upon accumulation of (p)ppGpp64.

(p)ppGpp-induced replication arrest mechanism(s) are also operational in other α-Proteobacteria25, as a nutritional down-shift induces a cell cycle arrest in S. meliloti65. Although CtrA is not known to bind the origin of replication in Sinorhizobium fredii directly10, CtrA may inhibit replication initiation indirectly as was recently also suggested to be the case for Caulobacter13 and reinforcement of CtrA by induced MopJ presents an appealing and conceivable possibility. This is mechanistically distinct from the (p)ppGpp-based replication arrest at the level of DNA primase described for the Gram-positive soil bacterium Bacillus subtilis66, a member of the Firmicutes, clearly showing that evolution has found elegant solutions to the same problem.

Methods

Growth conditions

Caulobacter crescentus NA1000 (ref. 43) and derivatives were cultivated at 30 °C in peptone yeast extract (PYE)-rich medium or in M2 minimal salts plus 0.2% glucose (M2G) supplemented by 0.4% liquid PYE5. E. coli S17-1 and EC100D (Epicentre Technologies) were cultivated at 37 °C in Luria Broth (LB)-rich medium. 1.5% agar was added into M2G or PYE plates and motility was assayed on PYE plates containing 0.3% agar. Antibiotic concentrations used for C. crescentus include kanamycin (solid: 20 μg ml−1; liquid: 5 μg ml−1), tetracycline (1 μg ml−1), spectinomycin (liquid: 25 μg ml−1), spectinomycin/streptomycin (solid: 30 and 5 μg ml−1, respectively), gentamycin (1 μg ml−1) and nalidixic acid (20 μg ml−1). When needed, D-xylose or sucrose was added at 0.3% final concentration, glucose at 0.2% final concentration and vanillate 500 or 50 μM final concentration. For the experiments in stationary phase in PYE, cultures with an OD660nm >1.4 were used.

Swarmer cell isolation, electroporation, biparental mating and bacteriophage φCr30-mediated generalized transduction were performed as described in ref. 5. Briefly, swarmer cells were isolated by Ludox or Percoll density-gradient centrifugation at 4 °C, followed by three washes and final re-suspension in pre-warmed (30 °C) M2G. Electroporation was done using 1 mm gap electroporation cuvettes at 1.5 kV in an Eppendorf 2510 electroporator and 6 ml exponential phase cells that had been washed three times in sterile water. Biparental matings were done using exponential phase E. coli S17-1 donor cells and Caulobacter recipient cells washed in PYE and mixed at 1:10 ratio on a PYE plate. After 4–5 h of incubation at 30 °C, the mixture of cells was plated on PYE harbouring nalidixic acid (to counter select E. coli) and the antibiotic that the conjugated plasmid confers resistance to. Generalized transductions were done by mixing 50 μl ultraviolet-inactivated transducing lysate with 500 μl exponential phase recipient cells, incubation for 2 h, followed by plating on PYE containing antibiotic to elect for the transduced DNA.

Bacterial strains, plasmids and oligonucleotides

Bacterial strains, plasmids and oligonucleotides used in this study are listed and described in Supplementary Tables 3–5, respectively.

Co-immunoprecipitation

When the culture (50 ml) reached OD660nm=0.4–0.6 in the presence of xylose, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6,000g for 10 min. The pellet was then washed in 10 ml of dilution/wash buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5); 150 mM NaCl; 0.5 mM EDTA) and lysed for 15 min at room temperature in 1 ml of lysis buffer (dilution/wash buffer+0.5% NP40, 10 mM MgCl2, two protease inhibitor tablets (for 50 ml of buffer; Complete EDTA-free, Roche), 1 × Ready-Lyse lysozyme (Epicentre), 50 U of DNase I )Roche)). Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 7,000g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was incubated for 1 h (or overnight) at 4 °C with GFP-Trap_A beads (ChromoTek GmbH) previously washed three times with 500 μl of dilution/wash buffer. The sample was then centrifuged at 2,500g for 2 min at 4 °C and the supernatant was removed. The beads were washed three times with 500 μl of dilution/wash buffer and finally resuspended in 2 × SDS sample buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 6.8), 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 1% β-mercaptoethanol, 12.5 mM EDTA, 0.02% Bromophenol Blue), heated to 95 °C for 10 min and stored at −20 °C.

Tandem affinity purification (TAP)

The TAP procedure was based on that described by ref. 55. Briefly, when the culture (1 l) reached OD660nm=0.4–0.6 in the presence of 50 μM vanillate, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6,000g for 10 min. The pellet was then washed in 50 ml of buffer I (50 mM sodium phosphate at pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) and lysed for 15 min at room temperature in 10 ml of buffer II (buffer I+0.5% n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside, 10 mM MgCl2, two protease inhibitor tablets (for 50 ml of buffer II; Complete EDTA-free, Roche), 1 × Ready-Lyse lysozyme (Epicentre), 500 U of DNase I (Roche)). Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 7,000g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was incubated for 2 h at 4 °C with IgG Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare Biosciences) that had been washed once with IPP150 buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP40). After incubation, the beads were washed at 4 °C three times with 10 ml of IPP150 buffer and once with 10 ml of TEV cleavage buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP40, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT). The beads were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with 1 ml of TEV solution (TEV cleavage buffer with 100 U of TEV protease per millilitre (Promega)) to release the tagged complex. CaCl2 (3 μM) was then added to the solution. The sample with 3 ml of calmodulin-binding buffer (10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM magnesium acetate, 1 mM imidazole, 2 mM CaCl2, 0.1% NP40) was incubated for 1 h at 4 °C with calmodulin beads (GE Healthcare Biosciences) that previously had been washed once with calmodulin-binding buffer. After incubation, the beads were washed three times with 10 ml of calmodulin-binding buffer and eluted five times with 200 μl IPP150 calmodulin elution buffer (calmodulin-binding buffer substituted with 2 mM EGTA instead of CaCl2). The eluates were then concentrated using Amicon Ultra-4 spin columns (Ambion).

β-Galactosidase assays

β-Galactosidase assays were performed at 30 °C as described previously3. 50 μl of cells grown in PYE at OD660nm=0.1–0.6 were lysed with chloroform and mixed with 750 μl of Z buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM KCl and 1 mM MgSO4 heptahydrate). 200 μl of ONPG (4 mg ml−1 o-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside in 0.1 M KPO4 pH 7.0) was added and the reaction timed. When a medium-yellow colour developed the reaction was stopped with 400 μl of 1 M Na2CO3. The OD420nm of the supernatant was determined and the units were calculated with the equation: U=(OD420nm × 1000)/(OD660nm × time (in min) × volume of culture (in ml)). For the stationary phase experiments, stationary phase cultures were diluted in PYE to obtain an OD660nm=0.1–0.6 and quickly lysed with chloroform. Following steps were performed as above. For GcrA depletion experiments in PYE using strain NA1000 ΔgcrA::Ω xylX::Pxyl-gcrA, PYE supplemented with 0.3% xylose overnight cultures were harvested and washed three times with PYE, and then restarted in appropriate PYE supplemented with 0.3% xylose or PYE supplemented with 0.2% glucose medium for 0, 1.5, 3, 4.5 and 6 h at 30 °C. Experimental values represent the averages of three independent experiments.

MopJ purification and production of antibodies

MopJ-short protein, lacking the first N-terminal 45 residues, was expressed from pET28a in E. coli Rosetta (DE3)/pLysS (Novagen) and purified under native conditions using Ni2+ chelate chromatography. A 5-ml overnight culture was diluted into 1 l of pre-warmed LB. When cells reached OD660nm=0.3–0.4, 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside was added to the culture and growth continued. After 3 h, cells were pelleted and resuspended in 25 ml of lysis buffer (10 mM Tris HCl (pH 8), 0.1 M NaCl, 1.0 mM b-mercaptoethanol, 5% glycerol, 0.5 mM imidazole Triton X-100 0.02%). Cells were sonicated (Sonifier Cell Disruptor B-30; Branson Sonic Power. Co.) on ice using 12 bursts of 20 s at output level 5.5. After centrifugation at 4,300g for 20 min, the supernatant was loaded onto a column containing 5 ml of Ni-NTA agarose resin pre-equilibrated with lysis buffer. Column was rinsed with lysis buffer, 400 mM NaCl and 10 mM imidazole, both prepared in lysis buffer. Fractions were collected (in 300 mM Imidazole buffer, prepared in lysis buffer) and used to immunize New Zealand white rabbits (Josman LLC).

Immunoblot analysis

Pelleted cells were re-suspended in 1 × SDS sample buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 1% β-mercaptoethanol, 12.5 mM EDTA, 0.02% Bromophenol Blue), heated to 95 °C for 10 min and stored at −20 °C. Protein samples were separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and blotted on polyvinylidenfluoride membranes (Merck Millipore). Membranes were blocked for 1 h with Tris-buffered saline (TBS), 0.05% Tween-20 and 5% dry milk and then incubated for an additional 1 h with the primary antibodies diluted in TBS, 0.05% Tween-20, 5% dry milk. The different polyclonal antisera to PilA (1:5,000 dilution), FljK (1:10,000), CtrA (1:10,000) and SciP (1:2,000) were used as described before10. The other antibodies were used at following dilutions: anti-GcrA (1:10,000)8, anti-MreB (1:20,000)67, anti-DivJ (1:10,000)32 and anti-MopJ (1:4,000). Commercial monoclonal (Roche, CH) and polyclonal antibodies to GFP were used at 1:5,000 and 1:10,000 dilutions, respectively. The membranes were washed four times for 5 min in PBS and incubated for 1 h with the secondary antibody (HRP-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibody, Jackson ImmunoResearch) diluted 1:20,000 in TBS, 0.05% Tween-20 and 5% dry milk. The membranes were finally washed again four times for 5 min in PBS and revealed with Immobilon Western Blotting Chemoluminescence HRP substrate (Merck Millipore) and Super RX-film (Fujifilm).

Microscopy

PYE or M2G cultivated cells in exponential growth phase were immobilized using a thin layer of 1% agarose. For time-lapse experiments, synchronized cells were immobilized using a thin layer of 1% agarose in M2G supplemented with 0.4% PYE. Fluorescence and contrast microscopy images were taken with an Alpha Plan-Apochromatic × 100/1.46 DIC(UV) VIS-IR oil objective on an Axio Imager M2 microscope (Zeiss) with acquisition at 535 nm (enhanced green fluorescent protein), 580 nm (yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)) and 480 nm (cyan fluorescent protein (CFP); Visitron Systems GmbH) and a Photometrics Evolve camera (Photometrics) controlled through Metamorph V7.5 (Universal Imaging). Images were processed using Metamorph V7.5.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

FACS experiments were performed as described previously50. Cells in exponential growth phase (OD660nm=0.3–0.6) or in stationary phase (diluted to obtain an OD660nm=0.3–0.6), cultivated in M2G, were fixed in ice-cold 70% ethanol solution. Fixed cells were re-suspended in FACS staining buffer, pH 7.2 (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCitrate, 0.01% Triton X-100) and then treated with RNase A (Roche) at 0.1 mg ml−1 for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were stained in FACS staining buffer containing 0.5 μM of SYTOX Green nucleic acid stain solution (Invitrogen) and then analysed using a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer instrument (BD Biosciences). Flow cytometry data were acquired and analysed using the CFlow Plus V1.0.264.15 software (Accuri Cytometers Inc.). 20,000 cells were analysed from each biological sample. The forward scattering (FSC-A) and Green fluorescence (FL1-A) parameters were used to estimate cell sizes and cell chromosome contents, respectively. Experimental values represent the averages of three independent experiments. Relative chromosome number was directly estimated from the FL1-A value of NA1000 cells treated with 20 μg ml−1 Rifampicin for 3 h at 30 °C, done in ref. 50. Rifampicin treatment of cells blocks the initiation of chromosomal replication, but allows ongoing rounds of replication to finish.

In vivo phosphorylation-immunoprecipitation experiments

In vivo phosphorylation measurements by 32P labelling of WT cultures harbouring pMT335 or pMT335-mopJ after induction with vanillate (50 μM), followed by immunoprecipitation with antibodies to DivK as described in the study by Radhakrishnan et al.3. Briefly, a freshly grown colony was picked from a PYE plate, washed with M5G medium lacking phosphate and was cultivated overnight in M5G with 0.05 mM phosphate to an optical density of 0.3 at 660 nm. One millilitre of culture was labelled for 4 min at 28 °C using 30 μCi of γ-[32P]ATP. Upon lysis, proteins were immunoprecipitated with 3 μl of anti-DivK antiserum and Protein A agarose (Roche, CH) and the precipitates were resolved by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and radiolabelled DivK was quantified.

Strain constructions

NA1000 ΔmopJ

Deletions were introduced using SacB-based counterselection using 3% sucrose. Briefly, pNPTS138-ΔmopJ-KO was first introduced into NA1000 (WT) by intergeneric conjugation and then plated on PYE harbouring kanamycin (to select for recombinants) and nalidixic acid to counter select E. coli donor cells5. A single homologous recombination event at the CCNA_00999 locus of kanamycin-resistant colonies was verified by PCR. The resulting strain was grown to stationary phase in PYE medium lacking kanamycin. Cells were then plated on PYE supplemented with 3% sucrose and incubated at 30 °C. Single colonies were picked and transferred in parallel onto plain PYE plates and PYE plates containing kanamycin. Kanamycin-sensitive cells, which had lost the integrated plasmid due to a second recombination event, leaving a deleted version of mopJ behind (ΔmopJ), were then identified for disruption of the mopJ locus by PCR.

NA1000 ΔspmXΔpodJ

pNPTS138-ΔspmX-KO3 was first introduced into NA1000 ΔpodJ36 by intergeneric conjugation and then plated on PYE harbouring kanamycin (to select for recombinants) and nalidixic acid to counter select E. coli donor cells. A single homologous recombination event at the CCNA_02255 locus of kanamycin-resistant colonies was verified by PCR. The resulting strain was treated as above.

NA1000 mopJ::himar1

mopJ::himar1 allele (himar1 insertion at nt 1082252, KanR) was transduced into NA1000 from NS61 using φCr30-mediated generalized transduction.

Strains harbouring pMT335 or pMT335-derived plasmids

pMT335 or pMT335-mopJ was introduced by electroporation and then plated on PYE plates harbouring gentamycin.

NA1000 ΔsocB ΔclpP::Ω and ΔsocB ΔclpX::Ω

The ΔclpP::Ω (SpcR) or ΔclpX::Ω (SpcR)19 allele was introduced into NA1000 ΔsocB as described in ref. 54 by φCr30-mediated transduction followed by selection on plates harbouring spectinomycin.

NA1000 xylX::P xyl -clpX*

pMO88 (ref. 68) was introduced into NA1000 by electroporation and then plated on PYE harbouring tetracycline. The resulting strain was grown to stationary phase in PYE medium containing tetracycline.

NA1000 ctrA::ctrA-M2 and ΔmopJ ctrA::ctrA-M2

The ctrA::ctrA-M2 allele45 was introduced into NA1000 or ΔmopJ by φCr30-mediated transduction on PYE plates harbouring kanamycin.

NA1000 ΔcpdR::tetR and ΔmopJ ΔcpdR::tetR

The ΔcpdR::tet (TetR) allele was transduced from ΔcpdR:: tet16 into NA1000 ΔmopJ followed by selection on PYE plates harbouring tetracycline.

Strains harbouring pMR10 or derivatives

Plasmids were introduced by electroporation, followed by selection of transformants on PYE plates harbouring tetracycline (pMR20) or kanamycin (pMR10).

Strains harbouring xylX::P xyl -mopJ-GFP

pCWR282 (pXGFP4-mopJ) was introduced into C. crescentus by electroporation and then plated on PYE harbouring kanamycin (to select for recombinants). A single homologous recombination event at the xyl locus of kanamycin-resistant colonies was verified by PCR.

Strains harbouring xylX::P xyl -divJ-GFP, xylX::P xyl -divJ392-GFP or xylX::P xyl -divJ329-GFP

pXGFP4-divJ, pXGFP4-divJ392 or pXGFP4-divJ329 were introduced into C. crescentus by electroporation and then plated on PYE harbouring kanamycin (to select for recombinants). A single homologous recombination event at the xyl locus of kanamycin-resistant colonies was verified by PCR.

Strains harbouring pMR10-divK-GFP and pMT335 or pMT335-mopJ

pMT335-mopJ was introduced into strains harbouring pMR10-divK-GFP (PdivK-divK-GFP) by electroporation and then plated on PYE harbouring kanamycin and gentamycin.

NA1000 mopJ::P mopJ -mopJ-GFP

pGFP4-mopJ was introduced into NA1000 ΔmopJ by electroporation and then plated on PYE harbouring kanamycin (to select for recombinants). A single homologous recombination event at the mopJ locus of kanamycin-resistant colonies was verified by PCR.

NA1000 xylX::P xyl -GFP-mopJ

pXGFP4-C1-GFP-mopJ was introduced into NA1000 by electroporation and then plated on PYE harbouring kanamycin. A single homologous recombination event at the xyl locus of kanamycin-resistant colonies was verified by PCR.

NA1000 xylX::P xyl -divK-CFP P van -mopJ-YFP

pMT374-mopJ-YFP was introduced into NA1000 xylX::Pxyl-divK-CFP17 by electroporation and then selected on PYE plates harbouring tetracycline and kanamycin.

Strains harbouring placZ290 or derivatives

placZ290 or derivatives10 were introduced into C. crescentus strains by electroporation and then plated on PYE harbouring tetracycline.

NA1000 xylX::pXTCYC4 placZ290-PmopJ

placZ290-PmopJ was introduced into NA1000 xylX::pXTCYC4 (ref. 47) by electroporation and then plated on PYE harbouring gentamycin and tetracycline.

NA1000 harbouring xylX::pXTCYC447, xylX::pXTCYC4-relA'-FLAG or xylX::pXTCYC4-relA'(E335Q)-FLAG and placZ290-PmopJ

placZ290-PmopJ was introduced into NA1000 xylX::pXTCYC4 (ref. 47), xylX::pXTCYC4-relA'-FLAG or xylX::pXTCYC4-relA'(E335Q)-FLAG47 by electroporation and then plated on PYE harbouring gentamycin and tetracycline.

NA1000 divL::divL-GFP and ΔmopJ divL::divL-GFP

divL-GFP::kan allele69 (KanR) was transduced into NA1000 ΔmopJ using φCr30-mediated generalized transduction.

divL::divL-GFP strains harbouring pMT335 or derivatives

Plasmids were introduced into divL::divL-GFP strains by electroporation and then plated on PYE harbouring kanamycin and gentamycin.

EC100D pET28a-mopJshort

pET28a-mopJshort was introduced into EC100D by electroporation and then plated on LB harbouring kanamycin.

Plasmid constructions

pCWR296 (pNPTS138-ΔmopJ-KO)

The plasmid construct used for mopJ (CCNA_00999) deletion was made by PCR amplification of two fragments. The first, a 568-bp fragment (nt 1081464–1082022, NA 1000 genome coordinates, flanked by an EcoRI site at the 5′end and a BamHI at the 3′end) was amplified using primers delmopJ_1-BamHI and delmopJ_1-EcoRI (sequences for all the primers used in this work can be found in Supplementary Table 5). The second, a 447-bp fragment (nt 1082446–1082880, flanked by a BamHI site at the 5′end and a HindIII site at the 3′end) was amplified using primers delmopJ_2-HindIII and delmopJ_2-BamHI. These two fragments were first digested with appropriate restriction enzymes and then triple ligated into pNTPS138 (M.R.K. Alley, Imperial College London, unpublished) that had been previously restricted with HindIII and EcoRI. This construct deletes 423 nt of the mopJ-coding sequence (nt 1082023–1082445, or codons 14–154 of the annotated CCNA_00999 coding sequence).

pMT335-mopJ (pUG16)

The mopJ-coding sequence (nt 1081990–1082481, NA1000 genome) was PCR amplified from the NA1000 strain using the mopJ-NdeI and mopJ-EcoRI primers. This fragment was digested with NdeI/EcoRI and cloned into NdeI/EcoRI-digested pMT335 (ref. 70).

pMT335-divJ

The divJ-coding sequence (nt 1220499–1222292) was PCR amplified from the NA1000 strain using the divJ-NdeI and divJ-MunI primers. This fragment was digested with NdeI/MunI and cloned into NdeI/EcoRI-digested pMT335.

pMT335-divJ392

The divJ392-coding sequence (short divJ form without sequence encoding for kinase domain, nt 1220499–1221674) was PCR amplified from the NA1000 strain using the divJ-NdeI and divJ392-MunI primers. This fragment was digested with NdeI/MunI and cloned into NdeI/EcoRI-digested pMT335.

pMT335-divJ329

The divJ329-coding sequence (short divJ form without sequence encoding for dimerization and kinase domains, nt 1220499–1221485) was PCR amplified from the NA1000 strain using the divJ-NdeI and divJ329-MunI primers. This fragment was digested with NdeI/MunI and cloned into NdeI/EcoRI-digested pMT335.

pXGFP4-divJ

The divJ-coding sequence without stop codon (nt 1220499–1222289) was PCR amplified from the NA1000 strain using the divJ-NdeI and divJ_fusion-MunI primers. This fragment was digested with NdeI/MunI and cloned into NdeI/EcoRI-digested pXGFP4 (M.R.K. Alley, Imperial College London, unpublished).

pXGFP4-divJ392

The divJ392-coding sequence (short divJ form without sequence encoding for kinase domain, nt 1220499–1221674) was PCR amplified from the NA1000 strain using the divJ-NdeI and divJ392fusion-MunI primers. This fragment was digested with NdeI/MunI and cloned into NdeI/EcoRI-digested pXGFP4.

pXGFP4-divJ329

The divJ329-coding sequence (short divJ form without sequence encoding for dimerization and kinase domains, nt 1220499–1221485) was PCR amplified from the NA1000 strain using the divJ-NdeI and divJ329fusion-MunI primers. This fragment was digested with NdeI/MunI and cloned into NdeI/EcoRI-digested pXGFP4.

pET28a-mopJshort

The mopJ-coding sequence lacking the first 132 bp from the start codon (nt 1082122–1082481) was PCR amplified from the NA1000 strain using the mopJshort-NdeI and mopJ-EcoRI primers. This fragment was digested with NdeI/EcoRI and cloned into NdeI/EcoRI-digested pET28a (Novagen).

pCWR282 (pXGFP4-mopJ)

The mopJ-coding sequence without stop codon (nt 1081990–1082478) was PCR amplified from the NA1000 strain using the mopJ-NdeI and mopJfusion-BamHI primers. This fragment was digested with NdeI/BamHI and cloned into NdeI/BamHI-digested pXGFP4.

pGFP4-mopJ

The mopJ-coding sequence without stop codon and the upstream region of 640 bp (nt 1081990–1082478) were PCR amplified from the NA1000 strain using the mopJ-NheI and mopJfusion-BamHI primers. This fragment was digested with NheI/BamHI and cloned into pXGFP4, previously digested with NheI/BamHI to remove the PxylX locus.

pXGFP4-C1-GFP-mopJ

The mopJ-coding sequence (nt 1081993–1082481), in which start codon ATG was replaced with GTC, was PCR amplified from the NA1000 strain using the mopJfusion-BglII and mopJ-EcoRI primers. This fragment was digested with BglII/EcoRI and cloned into BglII/EcoRI-digested pXGFP4-C1 (M.R.K. Alley, Imperial College London, unpublished).

placZ290-PmopJ

The mopJ promoter region (−228 to +78 relative to the ATG, nt 1081990–1081992) was PCR amplified using PmopJ-EcoRI and PmopJ-XbaI primers using NA1000 chromosomal DNA as a template. This fragment was digested by EcoRI-XbaI and cloned into EcoRI-XbaI-digested placZ290 promoter probe vector.

Author contributions

S.S., M.B., S.K.R. and P.H.V conceived and designed the experiments. S.S., M.B., L.T., S.K.R. and P.H.V. performed the experiments. S.S., M.B., S.K.R. and P.H.V analysed the data. S.S. and P.H.V. wrote the paper.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Sanselicio, S. et al. Topological control of the Caulobacter cell cycle circuitry by a polarized single-domain PAS protein. Nat. Commun. 6:7005 doi: 10.1038/ncomms8005 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-11, Supplementary Tables 1-5 and Supplementary References

Acknowledgments

Funding support is from SNF grant #31003A_143660 (to P.H.V.) and Fondation pour des bourses d'études Italo-Suisses (to S.S.). We thank Sean Crosson (University of Chicago), Jim Gober (UCLA), Kathleen Ryan (UC Berkeley), Lucy Shapiro (Stanford University), Urs Jenal (University of Basel), Mike Laub (MIT), Christine Jacobs-Wagner (Yale University) and Justine Collier (University of Lausanne) for materials, Gaël Panis for help with illustrations and FACS.

References

- Guttenplan S. B. & Kearns D. B. Regulation of flagellar motility during biofilm formation. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 37, 849–871 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skerker J. M. & Laub M. T. Cell-cycle progression and the generation of asymmetry in Caulobacter crescentus. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 325–337 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishnan S. K., Thanbichler M. & Viollier P. H. The dynamic interplay between a cell fate determinant and a lysozyme homolog drives the asymmetric division cycle of Caulobacter crescentus. Genes Dev. 22, 212–225 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quon K. C., Marczynski G. T. & Shapiro L. Cell cycle control by an essential bacterial two-component signal transduction protein. Cell 84, 83–93 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely B. Genetics of Caulobacter crescentus. Methods Enzymol. 204, 372–384 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardissone S. et al. Cell cycle constraints on capsulation and bacteriophage susceptibility. eLife 3, doi: 10.7554/eLife.03587 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laub M. T., Shapiro L. & McAdams H. H. Systems biology of Caulobacter. Annu. Rev. Genet. 41, 429–441 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzendorff J. et al. Oscillating global regulators control the genetic circuit driving a bacterial cell cycle. Science 304, 983–987 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiebig A. et al. A cell cycle and nutritional checkpoint controlling bacterial surface adhesion. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004101 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumeaux C. et al. Cell cycle transition from S-phase to G1 in Caulobacter is mediated by ancestral virulence regulators. Nat. Commun. 5, 4081 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laub M. T., McAdams H. H., Feldblyum T., Fraser C. M. & Shapiro L. Global analysis of the genetic network controlling a bacterial cell cycle. Science 290, 2144–2148 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quon K. C., Yang B., Domian I. J., Shapiro L. & Marczynski G. T. Negative control of bacterial DNA replication by a cell cycle regulatory protein that binds at the chromosome origin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 120–125 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastedo D. P. & Marczynski G. T. CtrA response regulator binding to the Caulobacter chromosome replication origin is required during nutrient and antibiotic stress as well as during cell cycle progression. Mol. Microbiol. 72, 139–154 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West A. H. & Stock A. M. Histidine kinases and response regulator proteins in two-component signaling systems. Trends Biochem. Sci. 26, 369–376 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsokos C. G., Perchuk B. S. & Laub M. T. A dynamic complex of signaling proteins uses polar localization to regulate cell-fate asymmetry in Caulobacter crescentus. Dev. Cell 20, 329–341 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biondi E. G. et al. Regulation of the bacterial cell cycle by an integrated genetic circuit. Nature 444, 899–904 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam H., Matroule J. Y. & Jacobs-Wagner C. The asymmetric spatial distribution of bacterial signal transduction proteins coordinates cell cycle events. Dev. Cell 5, 149–159 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien P., Perchuk B. S., Laub M. T., Sauer R. T. & Baker T. A. Direct and adaptor-mediated substrate recognition by an essential AAA+ protease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 6590–6595 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenal U. & Fuchs T. An essential protease involved in bacterial cell-cycle control. EMBO J. 17, 5658–5669 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iniesta A. A., McGrath P. T., Reisenauer A., McAdams H. H. & Shapiro L. A phospho-signaling pathway controls the localization and activity of a protease complex critical for bacterial cell cycle progression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 10935–10940 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung D. Y. & Shapiro L. A signal transduction protein cues proteolytic events critical to Caulobacter cell cycle progression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 13160–13165 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iniesta A. A., Hillson N. J. & Shapiro L. Cell pole-specific activation of a critical bacterial cell cycle kinase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 7012–7017 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Ohta N. & Newton A. An essential, multicomponent signal transduction pathway required for cell cycle regulation in Caulobacter. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 1443–1448 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Ohta N., Zhao J. L. & Newton A. A novel bacterial tyrosine kinase essential for cell division and differentiation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 13068–13073 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutte C. C. & Crosson S. Bacterial lifestyle shapes stringent response activation. Trends Microbiol. 21, 174–180 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesley J. A. & Shapiro L. SpoT regulates DnaA stability and initiation of DNA replication in carbon-starved Caulobacter crescentus. J. Bacteriol. 190, 6867–6880 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stott K. V. et al. (p)ppGpp modulates cell size and the initiation of DNA replication in Caulobacter crescentus in response to a block in lipid biosynthesis. Microbiology 161, 553–564 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutte C. C., Henry J. T. & Crosson S. ppGpp and polyphosphate modulate cell cycle progression in Caulobacter crescentus. J. Bacteriol. 194, 28–35 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutte C. C. & Crosson S. The complex logic of stringent response regulation in Caulobacter crescentus: starvation signalling in an oligotrophic environment. Mol. Microbiol. 80, 695–714 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsokos C. G. & Laub M. T. Polarity and cell fate asymmetry in Caulobacter crescentus. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 15, 744–750 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciochetti S. A., Lane T., Ohta N. & Newton A. Protein sequences and cellular factors required for polar localization of a histidine kinase in Caulobacter crescentus. J. Bacteriol. 184, 6037–6049 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler R. T. & Shapiro L. Differential localization of two histidine kinases controlling bacterial cell differentiation. Mol. Cell 4, 683–694 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul R. et al. Allosteric regulation of histidine kinases by their cognate response regulator determines cell fate. Cell 133, 452–461 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs C., Hung D. & Shapiro L. Dynamic localization of a cytoplasmic signal transduction response regulator controls morphogenesis during the Caulobacter cell cycle. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 4095–4100 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matroule J. Y., Lam H., Burnette D. T. & Jacobs-Wagner C. Cytokinesis monitoring during development; rapid pole-to-pole shuttling of a signaling protein by localized kinase and phosphatase in Caulobacter. Cell 118, 579–590 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viollier P. H., Sternheim N. & Shapiro L. Identification of a localization factor for the polar positioning of bacterial structural and regulatory proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 13831–13836 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinz A. J., Larson D. E., Smith C. S. & Brun Y. V. The Caulobacter crescentus polar organelle development protein PodJ is differentially localized and is required for polar targeting of the PleC development regulator. Mol. Microbiol. 47, 929–941 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman G. R. et al. Caulobacter PopZ forms a polar subdomain dictating sequential changes in pole composition and function. Mol. Microbiol. 76, 173–189 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman G. R. et al. A polymeric protein anchors the chromosomal origin/ParB complex at a bacterial cell pole. Cell 134, 945–955 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebersbach G., Briegel A., Jensen G. J. & Jacobs-Wagner C. A self-associating protein critical for chromosome attachment, division, and polar organization in Caulobacter. Cell 134, 956–968 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laloux G. & Jacobs-Wagner C. Spatiotemporal control of PopZ localization through cell cycle-coupled multimerization. J. Cell Biol. 201, 827–841 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry J. T., Crosson S. & Ligand-binding P. A. S. domains in a genomic, cellular, and structural context. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 65, 261–286 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks M. E. et al. The genetic basis of laboratory adaptation in Caulobacter crescentus. J. Bacteriol. 192, 3678–3688 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skerker J. M. & Shapiro L. Identification and cell cycle control of a novel pilus system in Caulobacter crescentus. EMBO J. 19, 3223–3234 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domian I. J., Quon K. C. & Shapiro L. Cell type-specific phosphorylation and proteolysis of a transcriptional regulator controls the G1-to-S transition in a bacterial cell cycle. Cell 90, 415–424 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potrykus K. & Cashel M. p)ppGpp: still magical? Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 62, 35–51 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez D. & Collier J. Effects of (p)ppGpp on the progression of the cell cycle of Caulobacter crescentus. J. Bacteriol. 196, 2514–2525 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis N. J. et al. De- and repolarization mechanism of flagellar morphogenesis during a bacterial cell cycle. Genes Dev. 27, 2049–2062 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fioravanti A. et al. DNA binding of the cell cycle transcriptional regulator GcrA depends on N6-adenosine methylation in Caulobacter crescentus and other Alphaproteobacteria. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003541 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray S. M., Panis G., Fumeaux C., Viollier P. H. & Howard M. Computational and genetic reduction of a cell cycle to its simplest, primordial components. PLoS Biol. 11, e1001749 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn J. M., Neher S. B., Kim Y. I., Sauer R. T. & Baker T. A. Proteomic discovery of cellular substrates of the ClpXP protease reveals five classes of ClpX-recognition signals. Mol. Cell 11, 671–683 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat N. H., Vass R. H., Stoddard P. R., Shin D. K. & Chien P. Identification of ClpP substrates in Caulobacter crescentus reveals a role for regulated proteolysis in bacterial development. Mol. Microbiol. 88, 1083–1092 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osteras M., Stotz A., Schmid Nuoffer S. & Jenal U. Identification and transcriptional control of the genes encoding the Caulobacter crescentus ClpXP protease. J. Bacteriol. 181, 3039–3050 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aakre C. D., Phung T. N., Huang D. & Laub M. T. A bacterial toxin inhibits DNA replication elongation through a direct interaction with the beta sliding clamp. Mol. Cell 52, 617–628 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig O. et al. The tandem affinity purification (TAP) method: a general procedure of protein complex purification. Methods 24, 218–229 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciochetti S. A., Ohta N. & Newton A. The role of polar localization in the function of an essential Caulobacter crescentus tyrosine kinase. Mol. Microbiol. 56, 1467–1480 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iniesta A. A., Hillson N. J. & Shapiro L. Polar remodeling and histidine kinase activation, which is essential for Caulobacter cell cycle progression, are dependent on DNA replication initiation. J. Bacteriol. 192, 3893–3902 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier J. Regulation of chromosomal replication in Caulobacter crescentus. Plasmid 67, 76–87 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis P. D. et al. The scaffolding and signalling functions of a localization factor impact polar development. Mol. Microbiol. 84, 712–735 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duerig A. et al. Second messenger-mediated spatiotemporal control of protein degradation regulates bacterial cell cycle progression. Genes Dev. 23, 93–104 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. C. et al. Cytokinesis signals truncation of the PodJ polarity factor by a cell cycle-regulated protease. EMBO J 25, 377–386 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas K., Liu J., Chien P. & Laub M. T. Proteotoxic stress induces a cell-cycle arrest by stimulating Lon to degrade the replication initiator DnaA. Cell 154, 623–636 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbatyuk B. & Marczynski G. T. Regulated degradation of chromosome replication proteins DnaA and CtrA in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol. Microbiol. 55, 1233–1245 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisonneuve E. & Gerdes K. Molecular mechanisms underlying bacterial persisters. Cell 157, 539–548 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Nisco N. J., Abo R. P., Wu C. M., Penterman J. & Walker G. C. Global analysis of cell cycle gene expression of the legume symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3217–3224 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. D., Sanders G. M. & Grossman A. D. Nutritional control of elongation of DNA replication by (p)ppGpp. Cell 128, 865–875 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figge R. M., Divakaruni A. V. & Gober J. W. MreB, the cell shape-determining bacterial actin homologue, co-ordinates cell wall morphogenesis in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol. Microbiol. 51, 1321–1332 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]