Abstract

The Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi is dependent on purine salvage from the host environment for survival. The genes bbb22 and bbb23 encode purine permeases that are essential for B. burgdorferi mouse infectivity. We now demonstrate the unique contributions of each of these genes to purine transport and murine infection. The affinities of spirochetes carrying bbb22 alone for hypoxanthine and adenine were similar to those of spirochetes carrying both genes. Spirochetes carrying bbb22 alone were able to achieve wild-type levels of adenine saturation but not hypoxanthine saturation, suggesting that maximal hypoxanthine uptake requires the presence of bbb23. Moreover, the purine transport activity conferred by bbb22 was dependent on an additional distal transcriptional start site located within the bbb23 open reading frame. The initial rates of uptake of hypoxanthine and adenine by spirochetes carrying bbb23 alone were below the level of detection. However, these spirochetes demonstrated a measurable increase in hypoxanthine uptake over a 30-min time course. Our findings indicate that bbb22-dependent adenine transport is essential for B. burgdorferi survival in mice. The bbb23 gene was dispensable for B. burgdorferi mouse infectivity, yet its presence was required along with that of bbb22 for B. burgdorferi to achieve maximal spirochete loads in infected mouse tissues. These data demonstrate that both genes, bbb22 and bbb23, are critical for B. burgdorferi to achieve wild-type infection of mice and that the differences in the capabilities of the two transporters may reflect distinct purine salvage needs that the spirochete encounters throughout its natural infectious cycle.

INTRODUCTION

Purine nucleobases are required for the synthesis of DNA and RNA. Consequently, purine biosynthesis and/or transport is a critical process across all kingdoms of life. Moreover, nucleobase transporters represent possible therapeutic targets for cancer and infectious diseases (1).

Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease, has a limited genome and lacks the enzymes required for de novo purine biosynthesis (2–6). Therefore, purine salvage from host environments is important for B. burgdorferi survival and pathogenesis (7–9). Recently, our laboratory established that the genes bbb22 and bbb23, located on B. burgdorferi essential circular plasmid 26 (cp26), together encode a purine transport system that is required for hypoxanthine transport and contributes to adenine and guanine transport (7). Spirochetes lacking both bbb22 and bbb23 are noninfectious in mice (7). Conversely, these genes are dispensable for B. burgdorferi growth in nutrient-rich medium in vitro (7).

The bbb22 and bbb23 genes encode proteins within cluster COG2252 of the nucleobase cation symporter-2 superfamily (NCS2) (7), which includes permeases found in bacteria, fungi, and plants that are specific for adenine, hypoxanthine, and/or guanine (10–16). The Aspergillus nidulans AzgA transporter, the founding member of this family of transporters, has specificity for adenine, hypoxanthine, and guanine (10, 11, 13). In other species, however, specific purine transport functions have been attributed to distinct proteins. For example, Escherichia coli harbors two high-affinity adenine permeases, PurP and YicO, and two high-affinity hypoxanthine-guanine permeases, YjcD and YgfQ (12, 15). Similarly, Bacillus subtilis has distinct uptake systems for hypoxanthine-guanine and adenine (16, 17). The Arabidopsis thaliana proteins Azg1 (AtAzg1) and AtAzg2 have been shown to be plant adenine-guanine transporters (14) although hypoxanthine uptake has yet to be examined for these proteins. The B. burgdorferi BBB22 and BBB23 open reading frames (ORFs) share 79.8% and 78.3% identity at the nucleic acid and amino acid levels, respectively, and are adjacent genes on cp26. This suggests that the two genes may be paralogs (7). Although the transport activities conferred by bbb22 and bbb23 together closely resemble the adenine-hypoxanthine-guanine permease function of AzgA (7, 10, 13), the individual contributions of bbb22 and bbb23 to the uptake of specific purines remain unknown. Although the overall amino acid sequences of the BBB22 and BBB23 proteins are highly conserved, sufficient sequence divergence may occur within two of the six putative periplasmic loops, which may allow for differential substrate specificity between the two proteins. In addition, it is possible that the two genes may confer the same transport functions but are differentially expressed (7).

Here, we analyzed the individual roles of bbb22 and bbb23 in purine transport and murine infection. Our findings demonstrated that BBB22 and BBB23 were each capable of hypoxanthine, adenine, and guanine uptake, albeit with differing affinities. Moreover, bbb22, but not bbb23, alone restored murine infectivity to Δbbb22-bbb23 (Δbbb22-23) spirochetes. Nonetheless, the spirochetes carrying bbb22 alone were unable to achieve spirochete loads in the infected mouse tissues equivalent to the bbb22-23+ spirochete loads. Together, these data suggest that both bbb22 and bbb23 are critical for B. burgdorferi to achieve wild-type levels of purine transport and mouse infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial clones and growth conditions.

Escherichia coli strain DH5α was grown in LB broth or on LB agar plates at 37°C. Gentamicin and spectinomycin were used at 10 μg/ml and 300 μg/ml, respectively. All B. burgdorferi clones were generated in the low-passage-number B31 A3-68-ΔBBE02-Δbbb22-23 clone, which lacks genes bbb22-23 and bbe02 and plasmids cp9 and linear plasmid 56 (lp56) (7). B. burgdorferi clones were grown in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly II (BSKII) medium at 35°C. Gentamicin, streptomycin, and kanamycin were used at 40 μg/ml, 50 μg/ml, and 200 μg/ml, respectively.

5′ RACE.

Total RNA was isolated with TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies) from a 50-ml culture of B. burgdorferi clone B31 A3 grown in BSKII medium to a density of 4 × 107 spirochetes/ml (log phase) or from a 5-ml culture at a density 2 × 108 spirochetes/ml (stationary phase). 5′ Rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5′ RACE) using a 5′ RACE System for Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends, version 2.0 (Life Technologies), was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Four micrograms of RNA was used per reaction volume along with gene-specific primers 1297, 1298, and 1299 for bbb22, primers 1316, 1317, and 1318 for the transcript within bbb23, and primers 1300, 1301, and 1302 for bbb23 (Table 1). Nested PCR products were purified using a PCR purification kit (Qiagen), and the 5′ end of each transcript was determined by sequence analysis (Genewiz).

TABLE 1.

Primers and probes used in this study

| Primer no. | Primer name | Sequence (5′–3′)a |

|---|---|---|

| 1006 | BBB23 ORF 1392-BamHI-Fwd | CCCGGGGGATCCTTGAAAATATTTTTAAACAATAAAAAGGAAAGTTT |

| 1007 | BBB23 ORF 1356-Fwd-BamHI | CCCGGGGGATCCATGGGTAAGTATGTAAAAGGTTTATTTTTT |

| 1011 | BBB23 ORF 1392-Rev-SalI | CCCGGGGTCGACTTACAGATCTTCTTCAGAAATAAGTTTTTGTTCATAGCC |

| 1123 | recA-F | AATAAGGATGAGGATTGGTG |

| 1124 | recA-R | GAACCTCAAGTCTAAGAGATG |

| 1137 | flaB-TaqMan-Fwd | TCTTTTCTCTGGTGAGGGAGCT |

| 1037 | pUC18F | CCCAGTCACGACGTTGTAAAAC |

| 1138 | flaB-TaqMan-Rev | TCCTTCCTGTTGAACACCCTCT |

| 1140 | nid-TaqMan-Fwd | CACCCAGCTTCGGCTCAGTA |

| 1141 | nid-TaqMan-Rev | TCCCCAGGCCATCGGT |

| 1166 | BBB23 TaqMan Fwd | GCACTAGTTACCGCAACCTGTCT |

| 1167 | BBB23 TaqMan Rev | CTCATTCCAGAAGCCAATGCT |

| 1168 | BBB22 TaqMan Fwd | GAATCAATCCAAAGAAACATTGTTAT |

| 1169 | BBB22 TaqMan Rev | AGTTGCAGTAACTAATGCGCCAAT |

| 1297 | BBB22 GSP-1A | TACTGCGCTTTCTGGAC |

| 1298 | BBB22 GSP-1B | AATTTGCAATACTTTCCCTAGC |

| 1299 | BBB22 GSP-1D | GCTGATGTTAAGCAAGTTGCAG |

| 1300 | BBB23 GSP-1A | CCTGGGCACCTTCTAAAT |

| 1301 | BBB23 GSP-1B | AGTTTATAATTTGCTCCCTTACTC |

| 1302 | BBB23 GSP-1D | TGCTGTTAGACAGGTTGCG |

| 1316 | BBB22 IVET RACE GSP1 | GGCAAAAAAAACTGCAAATAGAAATAATG |

| 1317 | BBB22 IVET RACE GSP2 | GCCGTCTACCAGTAATATTTTTTTTGC |

| 1318 | BBB22 IVET RACE GSP3 | ATTGAACAAGAGAATAAAAACTATTGATATAAAAGTCC |

| 1525 | BBB23-cmyc-HindIII Rev | CCCGGGAAGCTTTTACAGATCTTCTTCAGAAATAAGTTTTTGTTCATAGCCA TAAATAAATTTAATAATAAAAATTAAGC |

| 1526 | BBB23 promoter KpnI Fwd | CCCGGGGGTACCTATTTTCAAACTTTACCTGACAGCG |

| 1527 | BBB23 promoter BamHI Rev | CCCGGGGGATCCTAATAATTATTAGGCTTTTAATTCTTTTTAAA |

| 1528 | BBB22 BamHI-Fwd | CGGGATCCTCTCCTGTACTGCTAATATTATGC |

| 1529 | BBB22 HindIII- Rev | CCCAAGCTTGACTCTTTTTTATGATTTATAATTTAGG |

| 1577 | flaBp-fwd-KpnI | CCCGGGGGTACCTGTCTGTCGCCTCTTGTGGCT |

| 1578 | flaBp-Rev-BamHI | GGGGGATCCGATTGATAATCATATATCATTCCT |

| 1668 | pUC18R | AGCGGATAACAATTTCACACAG |

| 1139 | flaB TaqMan probe | 6-FAM-AAACTGCTCAGGCTGCACCGGTTC-TAMRA |

| 1142 | nid TaqMan probe | 6-FAM-CGCCTTTCCTGGCTGACTTGGACA-TAMRA |

| 1575 | BBB22 TaqMan probe | 6-FAM-AGCATGGCATACATAATAGCTGTTAATCCGGC-TAMRA |

| 1576 | BBB23 TaqMan probe | 6-FAM-CTAATGGGACTTTATACCAATACGCCTT-TAMRA |

FAM, 6-carboxyfluorescein; TAMRA, 6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine. Restriction sites are in boldface.

Generation of plasmids containing bbb22 and bbb23.

A sequence region of 107 bp upstream of the BBB23 ORF containing the bbb23 promoter (23p) (7) and flaB promoter sequence were amplified from B. burgdorferi B31 clone A3 genomic DNA using Phusion enzyme (Thermo Scientific) and the primer pair 1526 and 1527 and the pair 1577 and 1578 (Table 1), respectively. The B. burgdorferi shuttle vector pBSV2G (18) and promoter fragments were digested with restriction enzymes KpnI and BamHI, ligated, and cloned in E. coli. Plasmids were confirmed by restriction digestion and DNA sequence analysis. The annotated BBB23 ORF sequence was amplified from B31 A3 genomic DNA using Phusion enzyme (Thermo Scientific) and the primer pair 1006 and 1525. A subsequent PCR using the primer pair 1006 and 1011 (Table 1) and the PCR product derived from primer pair 1006 and 1525 (Table 1) as a template was used to replace the 3′ HindIII restriction site with SalI. The bbb23 gene was ligated into pBSV2G 23p and pBSV2G flaBp plasmids using restriction enzymes BamHI and SalI and cloned in E. coli. Plasmids pBSV2G 23p-bbb23+ and pBSV2G flaBp-bbb23+ were confirmed by restriction digestion and DNA sequence analysis. DNA fragments containing the bbb22 ORF and 1,466 bp of upstream sequence (bbb22 distal promoter, 22distp) or the bbb22 ORF and 160 bp of upstream sequence (bbb22 proximal promoter, 22proxp) were amplified from B31 A3 genomic DNA using Phusion enzyme (Thermo Scientific) and the primer pair 1007 and 1529 and the pair 1528 and 1529, respectively (Table 1). The DNA fragments were ligated into the pBSV2G vector using BamHI and HindIII restriction sites and the plasmids were cloned in E. coli. Plasmids pBSV2G 22distp-bbb22+ and pBSV2G 22proxp-bbb22+ were confirmed by restriction digestion and DNA sequence analysis (Genewiz).

Reintroduction of bbb22 and bbb23 into bbb22-23 mutant spirochetes.

B. burgdorferi clone B31 A3-68-ΔBBE02-Δbbb22-23 was transformed with 20 μg of plasmid pBSV2G 23p-bbb23+, pBSV2G flaBp-bbb23+, pBSV2G 22proxp-bbb22+, or pBSV2G 22distp-bbb22+, and the transformants were selected in BSK1.5X semisolid medium containing 1.7% agarose and 40 μg/ml gentamicin at 37°C in 2.5% CO2 for 6 to 8 days. B. burgdorferi transformants were confirmed by colony PCR using primers 1037 and 1668 (Table 1). The endogenous plasmid content of each new B. burgdorferi clone was confirmed by PCR analysis (8) to be the same as that of the B31 A3-68-Δbbe02-Δbbb22-23 parent clone (7) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

B. burgdorferi clones used in this study

| B. burgdorferi clonea | Shuttle vector | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Δbbb22-23 | pBSV2G | 7 |

| bbb22-23+ | pBSV2G bbb22-23+ | 7 |

| 23p-bbb23+ | pBSV2G 23p-bbb23+ | This work |

| flaBp-bbb23+ | pBSV2G flaBp-bbb23+ | This work |

| 22proxp-bbb22+ | pBSV2G 22proxp-bbb22+ | This work |

| 22distp-bbb22+ | pBSV2G 22distp-bbb22+ | This work |

All of the clones had the following genotype: B31 A3-68 bbe02::flgBp-kan bbb22-23::flaBp-aadA cp9− lp56−.

RNA extraction from in vitro-grown cultures.

B. burgdorferi clones bbb22-23+, Δbbb22-23, 23p-bbb23+, flaBp-bbb23+, 22proxp-bbb22+, and 22distp-bbb22+ (Table 2) were grown to a density of 2 × 108 spirochetes/ml in BSKII medium containing the appropriate antibiotics. A total of 2 × 108 spirochetes were harvested at 5,800 × g for 10 min. RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies) or a Direct-zol RNA miniprep kit (Epigenetics) and resuspended in 50 μl of diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated distilled H2O (dH2O). RNA samples were DNase treated using Turbo DNA-free (Life Technologies) and were confirmed to be free of B. burgdorferi genomic DNA contamination by PCR using primers 1123 and 1124. One microliter of SUPERaseIn RNase inhibitor (Life Technologies) was added to prevent RNA degradation, and samples were stored at −80°C.

Gene expression analysis.

A total of 400 ng of B. burgdorferi RNA, extracted from late stationary-phase spirochetes as described above, was used to synthesize cDNA with an iScript Select cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) using random hexamer primers. Reaction mixtures lacking reverse transcriptase were run in tandem as negative controls. TaqMan real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using 400 ng of cDNA, IQ Super Mix (Bio-Rad), and the following primer/probe sets: 1168, 1169, and 1575 (bbb22); 1166, 1167, and 1576 (bbb23); and 1137, 1138, and 1139 (flaB) (Table 1). mRNA transcript copy numbers for bbb22 and bbb23 were normalized to flaB mRNA copy numbers. All data sets were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey's posttest (GraphPad Prism, version 5.0).

Radioactive transport assays.

B. burgdorferi clones were grown to a state of late stationary-phase starvation at a density of 2 × 108 spirochetes/ml. Radioactive transport assays were performed as previously described (7). Briefly, to initiate the metabolism of the starved spirochetes, the bacteria were preincubated at 37°C for 30 min in 1-ml reaction volumes containing HN buffer (50 mM HEPES and 50 mM NaCl, pH 7.4), 6 mM glucose, and 1.4% rabbit serum (Pelfreez). This amount of rabbit serum was estimated to contain ∼90 nM hypoxanthine and ∼5 nM adenine (19, 20), both of which represented less than 10% of the lowest concentrations of [3H]hypoxanthine and [3H]adenine used in the kinetic assays described below. Thirty-minute uptake experiments were performed using 2.5 μM [3H]hypoxanthine monohydrochloride (specific activity, 20 Ci/mmol) (PerkinElmer) or 0.396 μM [2,8-3H]adenine (specific activity, 15 Ci/mmol) (PerkinElmer), and samples were analyzed at 10 s and 2, 5, 8, 15, and 30 min following the addition of radioactivity. The amounts of hypoxanthine and adenine uptake were converted to femtomoles/5 × 107 spirochetes as previously described (7). Initial rate experiments were performed using 1.0 to 2.5 μM [3H]hypoxanthine monohydrochloride (specific activity, 20 Ci/mmol) (PerkinElmer) or 0.066 to 0.396 μM [2,8-3H]adenine (specific activity, 15 Ci/mmol) (PerkinElmer), and samples were analyzed at 10, 20, 30, 45, and 60 s following the addition of radioactivity. The rates of purine uptake (fmol/5 × 107 spirochetes/s) were estimated for each purine concentration by linear regression, and the Km values were determined using GraphPad Prism, version 5.0. Data sets were compared using an unpaired t test or two-way ANOVA using GraphPad Prism, version 5.0.

For the [3H]hypoxanthine uptake assays in the presence of cold competitors, B. burgdorferi clones were grown and prepared as described above. Stock solutions (1 mM) of each cold competitor, hypoxanthine, guanine, adenine, and cytosine, were prepared in 8 mM NaOH. All the reactions were carried out in a 1-ml volume containing 1 × 109 spirochetes, 250 nM [3H]hypoxanthine, and either 5 μl of cold competitor (5 μM final concentration, 20-fold excess) or 5 μl of 8 mM NaOH alone (40 μM final concentration). This final concentration of NaOH in the reaction mixture was not found to affect the ability of the spirochetes to transport [3H]hypoxanthine (data not shown). Aliquots (100 μl) containing 108 spirochetes were removed 15 min following the addition of radioactivity and were analyzed as previously described (7). The percent [3H]hypoxanthine uptake for each reaction condition was calculated relative to the amount of [3H]hypoxanthine transport in the absence of competitor. bbb22-23+ spirochetes (Table 2) heated to 95°C for 15 min (heat killed) served as the negative control for all transport experiments.

Mouse infection experiments.

The University of Central Florida (UCF) is accredited by International Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. All the mouse experiments were done according to the guidelines of National Institutes of Health (NIH) and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of UCF. Groups of 6- to 8-week-old C3H/HeN female mice (Harlan) were inoculated with B. burgdorferi clone bbb22-23+, Δbbb22-23, 23p-bbb23+, flaBp-bbb23+, 22proxp-bbb22+, or 22distp-bbb22+ (Table 2). Mice were inoculated intraperitoneally (80%) and subcutaneously (20%) with a total dose of 1 × 104 or 1 × 107 spirochetes. Inoculum cultures were analyzed for the endogenous plasmid content by PCR and plated on solid BSK medium, and individual colonies from each population were analyzed for the presence of virulence plasmids lp25, lp28-1, and lp36 (9). All inoculum cultures carried the expected endogenous plasmid content (Table 2), and 70 to 100% of individual colonies from each clone were confirmed to contain all three virulence plasmids. Blood for serological analysis was collected prior to inoculation and at 3 weeks postinoculation. Mouse infection was determined by serology and spirochete reisolation from tissues as previously described (7).

Quantitation of spirochete loads in mouse tissues.

Ear, heart, and joint tissues were collected for DNA extraction from mice 3 weeks postinoculation. DNA extraction was performed as previously described (8). Real-time quantitative PCR was performed using 100 ng of DNA from infected mouse tissues. The number of B. burgdorferi genomes was determined using the standard curve method to quantify the number of B. burgdorferi flaB copies using flaB primers (1137 and 1138) and probe (1139) (96% efficiency). The standard curve for B. burgdorferi DNA was generated using 0.001 ng, 0.01 ng, 0.1 ng, 1.0 ng, and 10.0 ng of B. burgdorferi genomic DNA. Our assay was found to have a limit of detection of 5 to 10 B. burgdorferi genomes per reaction. The number of mouse genomes was quantified using mouse nid primers (1140 and 1141) and probe (1142) (100% efficiency) (Table 1). The standard curve for mouse DNA was generated using 5.5 × 103, 5.5 × 104, 5.5 × 105, and 5.5 × 106 nid copies (8). All qPCRs were performed using IQ supermix (Bio-Rad), as previously described (8). The data were reported as the number of B. burgdorferi genomes/104 mouse genomes, and the data sets were compared using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's posttest using GraphPad Prism, version 5.0.

RESULTS

The bbb22 and bbb23 genes are separate transcripts.

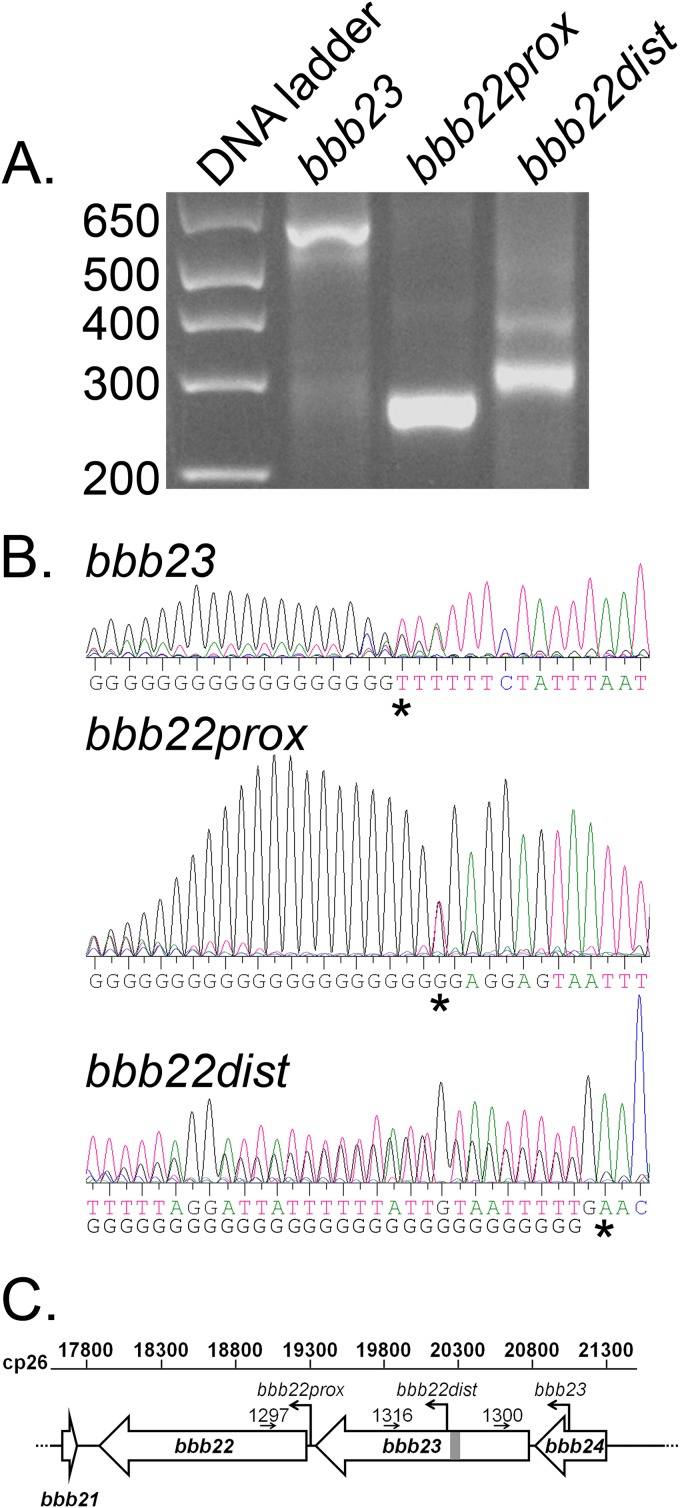

We previously demonstrated that genes bbb22-23, present on circular plasmid 26 (cp26), encode purine permeases and together are essential for B. burgdorferi mouse infection (7). However, the individual contributions of bbb22 and bbb23 to purine transport and mouse infection remain unknown. The annotated bbb22 and bbb23 open reading frames are separated by a 109-bp intergenic region (4), suggesting that these two genes may be transcribed separately and therefore may play distinct roles in the ability of B. burgdorferi to salvage purines. Rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) was used to identify the 5′ ends of the bbb22 and bbb23 transcripts. The transcription start site for bbb23 was found to be 260 bp upstream of the annotated bbb23 open reading frame (ORF), which corresponds to nucleotide 21082 on cp26 and is 225 bp within the 3′ end of bbb24 (Fig. 1). The transcription start site for bbb22 (bbb22prox) was found to be 16 bp upstream of the annotated bbb22 ORF at nucleotide 19338 on cp26 (Fig. 1). In addition, an in vivo expression technology (IVET)-based genetic screen performed by our laboratory to identify B. burgdorferi sequences that are expressed during murine infection (21) identified a candidate promoter sequence (B. burgdorferi IVE fragment 103 [Bbive103], nucleotides 20322 to 20238 on cp26) within and in the same orientation to the bbb23 ORF. Consistent with this finding, 5′ RACE analysis using RNA isolated from in vitro-grown spirochetes validated the presence of a transcription start site at nucleotide 20219, 17 bp downstream of the Bbive103 sequence (bbb22dist) (Fig. 1), indicating that this promoter is active both in vitro and in vivo. The double sequence observed in the sequence analysis of the bbb22dist 5′ RACE PCR product (Fig. 1B) reflects detection of both the transcript derived from the putative distal promoter for bbb22 and the bbb23 transcript itself. Together, these data indicate that bbb23 and bbb22 have distinct transcription start sites and that an additional transcription start site is present 897 bp upstream of bbb22 within bbb23.

FIG 1.

Genes bbb22 and bbb23 each harbor their own promoters. Rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5′ RACE) analysis of the transcription start sites for the bbb23, bbb22prox, and bbb22dist transcripts was performed using RNA extracted from B31 clone A3 B. burgdorferi. (A) Transcript-specific 5′ anchored nested PCR products generated from the 5′ RACE analysis. Data shown are representative of two replicate experiments. The DNA ladder is shown in base pairs. (B) DNA sequence chromatographs of the DNA sequence of the 5′ RACE products shown in panel A. Both sequences detected for bbb22dist are shown. The 5′ nucleotide of each transcript is indicated with a star. (C) Schematic diagram of the genetic organization of genes bbb22 and bbb23. Transcription start sites identified in panel B are shown as bent arrows and labeled with the corresponding transcripts names. The B. burgdorferi IVET in vivo active promoter sequence within the BBB23 ORF is shown as a light gray box. The locations and numbers of the transcript-specific primers used to generate the cDNA for the 5′ RACE analysis are indicated. A ruler for the nucleotide coordinates on cp26 is shown.

A long 5′ UTR within bbb23 is required for wild-type expression of bbb22.

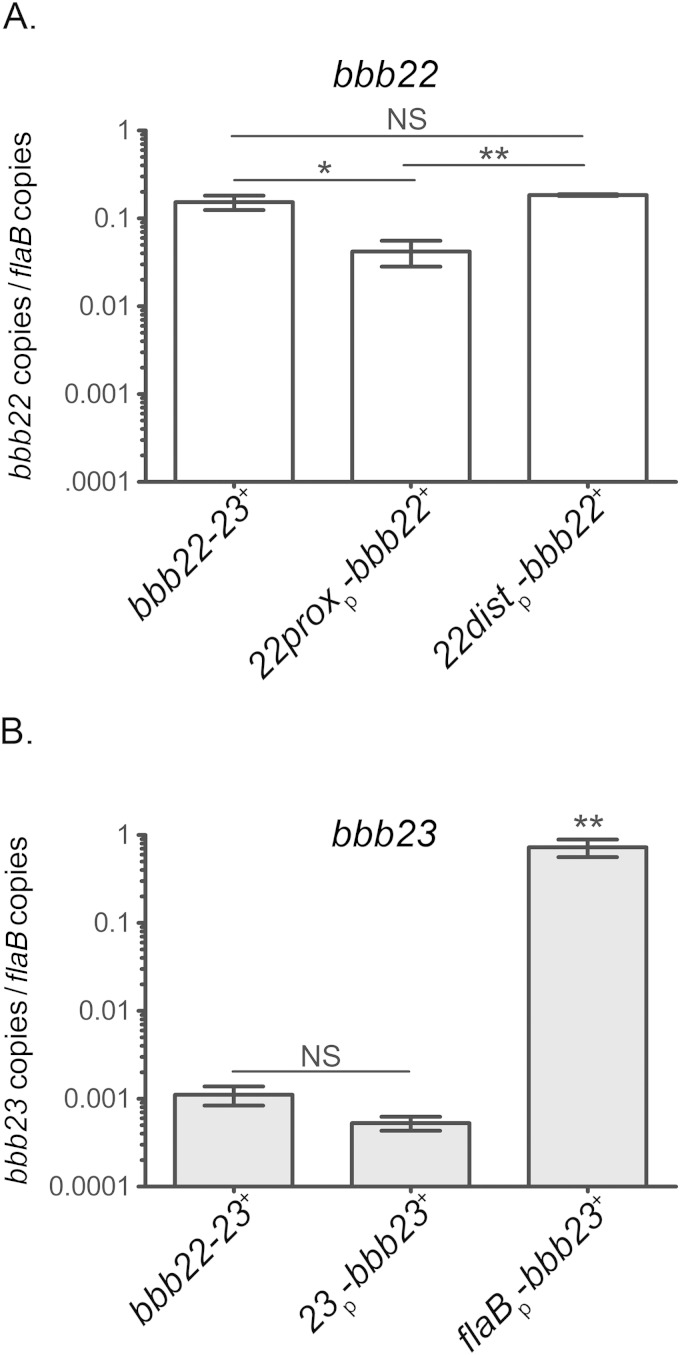

Toward the goal of understanding the individual roles of bbb22 and bbb23, a panel of plasmids was engineered using the B. burgdorferi shuttle vector pBSV2G (18) to contain the bbb23 ORF along with its endogenous promoter sequence (23p-bbb23+), the bbb23 ORF along with the constitutive flaB promoter (flaBp-bbb23+), the bbb22 ORF along with the proximal promoter sequence (22proxp-bbb22+), or the bbb22 ORF along with the proximal and distal promoter sequences (22distp-bbb22+) (Table 2). In order to generate spirochetes that harbored only bbb22 or bbb23, the shuttle vector plasmids carrying bbb23 or bbb22 were each transformed into a low-passage-number B. burgdorferi clone that lacks both bbb22 and bbb23 (7). All B. burgdorferi transformants were verified to contain all of the endogenous plasmid replicons present in the Δbbb22-bbb23 mutant parent (Table 2). The in vitro gene expression of bbb22 and/or bbb23 was analyzed in the B. burgdorferi clones bbb22-23+, 22proxp-bbb22+, 22distp-bbb22+, 23p-bbb23+, and flaBp-bbb23+ (Table 2). Each was grown to late stationary phase, a starvation condition that we have previously demonstrated to induce purine permease activity (7) (Fig. 2). The levels of bbb22 and bbb23 expression in the bbb22-bbb23+ clone were equivalent to the levels of expression of these genes in wild-type spirochetes (data not shown). The expression level of bbb22 under the control of the proximal promoter alone (22proxp-bbb22+) was significantly reduced compared to the level of bbb22 expression in the bbb22-23+ positive-control spirochetes (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, the level of bbb22 expression in 22distp-bbb22+ spirochetes was similar to that of bbb22-23+ spirochetes (Fig. 2A). Together, these data suggest a possible role for the long 5′ untranslated region (UTR) in the 22distp-bbb22+ construct in the regulation of wild-type levels of bbb22. There was no significant difference detected between the levels of bbb23 transcription in 23p-bbb23+ spirochetes and levels in bbb22-23+ spirochetes (Fig. 2B), suggesting that the upstream sequence included in this construct was sufficient to drive bbb23 expression to wild-type levels. It was observed that in late stationary-phase growth, the level of bbb23 expression in bbb22-23+ spirochetes (Fig. 2B) was approximately 100-fold lower than the level of bbb22 expression in the same clone (Fig. 2A). A similar, significant difference between the levels of late stationary-phase expression of bbb22 and bbb23 was detected in wild-type spirochetes (data not shown). We found that by driving expression of bbb23 under the control of the constitutive promoter flaB, the level of bbb23 expression in late stationary phase could be increased to a level similar to that of bbb22 under the control of its endogenous promoter (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

In vitro gene expression of bbb22 and bbb23 in B. burgdorferi clones. RNA was extracted from bbb22-23+, 23p-bbb23 +, flaBp-bbb23+, 22proxp-bbb22+, and 22distp-bbb22+ B. burgdorferi clones at late stationary phase (2 × 108 spirochetes/ml) grown at 37°C. Gene expression for bbb22, bbb23, and flaB was quantified by reverse transcriptase qPCR. (A) bbb22 expression was analyzed for clones bbb22-23+, 22proxp-bbb22+, and 22distp-bbb22+. bbb22 mRNA transcripts were normalized to the number of flaB mRNA copies. (B) bbb23 expression was analyzed for clones bbb22-23+, 23p-bbb23+, and flaBp-bbb23+. bbb23 mRNA transcripts were normalized to the number of flaB mRNA copies. Data represent the average values of three biological replicates. Error bars represent the standard deviations from the means. The y axis is depicted in a log10 scale. Data sets were compared by one-way ANOVA using GraphPad Prism, version 5.0. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; NS, not significant.

Both bbb22 and bbb23 are necessary for B. burgdorferi to achieve wild-type levels of hypoxanthine transport.

We previously demonstrated the combined roles of bbb22 and bbb23 in hypoxanthine transport (7). To determine the ability of spirochetes harboring either bbb22 or bbb23 alone to transport hypoxanthine, uptake assays were performed using a panel of B. burgdorferi clones carrying either bbb22 or bbb23 (Table 2). Hypoxanthine uptake was measured using 2.5 μM [3H]hypoxanthine over a 30-min time course. This concentration of hypoxanthine is similar to the physiological concentration of hypoxanthine in mammalian plasma (22). The amounts of [3H]hypoxanthine detected in the spirochetes carrying only bbb22 or bbb23 were significantly reduced compared to the amounts in the bbb22-23+ clone (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, spirochetes carrying bbb22 alone driven by the long 5′ UTR sequence (22distp-bbb22+) demonstrated statistically significantly increased levels of hypoxanthine uptake relative to the levels of both the Δbbb22-23 mutant and heat-killed spirochetes at time points 5, 8, 15, and 30 min, further suggesting a role for the long 5′ UTR sequence in bbb22 function. However, the maximum amount of hypoxanthine uptake achieved by 22distp-bbb22+ spirochetes was significantly reduced compared to that of spirochetes carrying both the bbb22 and bbb23 genes (Fig. 3A). In addition, hypoxanthine uptake by 22distp-bbb22+ spirochetes reached saturation in the first 5 min of the assay. In contrast, bbb22-bbb23+ spirochetes demonstrated an increase in hypoxanthine uptake out to 15 min prior to reaching saturation. These data suggest that although spirochetes carrying bbb22 alone are capable of transporting hypoxanthine, this function is significantly reduced in the absence of bbb23. We further examined the hypoxanthine transport function conferred by bbb22 alone by calculating the Km values for hypoxanthine for clones 22distp-bbb22+ and bbb22-bbb23+ based on the initial rates of hypoxanthine uptake for these clones across increasing concentrations of hypoxanthine. We found that the Km for hypoxanthine for 22distp-bbb22+ spirochetes was no different from the Km for hypoxanthine for bbb22-bbb23+ spirochetes (2.6 ± 0.1 μM and 3.4 ± 0.5 μM, respectively) (Table 3). These findings indicate that the absence of bbb23 in 22distp-bbb22+ spirochetes did not result in a significant alteration in the affinity for hypoxanthine uptake. As expected, the Δbbb22-23 mutant and heat-killed spirochetes demonstrated no increase in the amount of [3H]hypoxanthine uptake over the 30-min time course (Fig. 3A) (7). Similarly, no increase in the amount of [3H]hypoxanthine uptake was detected for the 23p-bbb23+ and 22proxp-bbb22+ spirochetes over the time period of the assay, suggesting that these clones were unable to transport hypoxanthine. The amounts of hypoxanthine transported by spirochetes carrying the bbb23 gene alone under the control of the constitutive flaB promoter over the 30-min time course were not found to be statistically different from the background levels detected in the Δbbb22-23 mutant and heat-killed spirochetes. However, unlike the Δbbb22-23 mutant and heat-killed spirochetes, the flaBp-bbb23+ spirochetes demonstrated a statistically significant increase in hypoxanthine uptake between the 10-s and 15-min time points (P = 0.0009, unpaired t test) (Fig. 3A), suggesting that bbb23 alone may confer weak hypoxanthine transport activity. The initial rates of hypoxanthine uptake by flaBp-bbb23+ spirochetes were found to be too low to allow accurate determination of the Km for hypoxanthine for this clone (data not shown). Together these data indicate that individually the bbb22 gene and possibly the bbb23 gene are each capable of providing B. burgdorferi with a minimal capacity for hypoxanthine transport, suggesting a synergistic role for the two genes together for the ability of B. burgdorferi to transport wild-type levels of hypoxanthine.

FIG 3.

bbb22 and bbb23 alone provide spirochetes with distinct abilities to take up purines. Radioactive purine uptake by B. burgdorferi bbb22-23+, 23p-bbb23+, flaBp-bbb23+, 22proxp-bbb22+, 22distp-bbb22+, Δbbb22-23, and bbb22-23+ heat-killed spirochetes was measured over a 30-min time course following the addition of 2.5 μM [3H]hypoxanthine (A) or 0.396 μM [2,8-3H]adenine (B).The specific activity of the labeled hypoxanthine used was 20 Ci/mmol. The specific activity of the labeled adenine used was 15 Ci/mmol. Error bars represent the standard deviation from the mean for at least two biological replicates.

TABLE 3.

Affinities for hypoxanthine and adenine of spirochetes carrying bbb22 alone or both bbb22 and bbb23

| Clone |

Km (μM) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Hypoxanthine | Adenine | |

| bbb22-23+ | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 0.13 ± 0.04 |

| 22distp-bbb22+ | 2.6 ± 0.10 | 0.19 ± 0.01 |

The bbb22 gene alone allows spirochetes to take up wild-type steady-state levels of adenine.

It has been previously demonstrated that genes bbb22-23 contribute to the ability of B. burgdorferi to undergo rapid transport of adenine (7) (Fig. 3B). In addition, B. burgdorferi is able to transport adenine in the absence of bbb22-23, albeit at a much lower rate, likely due to the function of an additional, as of yet unknown, adenine transporter(s) (7) (Fig. 3B). To understand the individual contributions of bbb22 and bbb23 to adenine uptake, the B. burgdorferi clones carrying only one or the other gene were analyzed over a 30-min time course at a physiologically relevant concentration of [3H]adenine of 0.396 μM (22). Similar to what was observed for hypoxanthine transport, clones 23p-bbb23+ and 22proxp-bbb22+ demonstrated no detectable increase in adenine transport relative to the Δbbb22-23 mutant. The amounts of adenine uptake detected in the two clones at the 30-min time point were significantly reduced compared to the level in the Δbbb22-23 mutant but not statistically different from that in heat-killed spirochetes. The addition of the bbb23 gene under the control of the flaB promoter did not provide the Δbbb22-23 mutant with any increased ability to transport adenine. Together, these data indicate that bbb23 alone and bbb22 under the control of the proximal promoter do not confer adenine transport activity (Fig. 3B). In contrast, 22distp-bbb22+ spirochetes demonstrated a significant increase in adenine uptake compared to that of the bbb22-23 mutant (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, with the exception of the 2-min time point, there was no statistical difference between the adenine uptake by 22distp-bbb22+ spirochetes and that of spirochetes harboring both genes (Fig. 3B). The 22distp-bbb22+ spirochetes reached the same level of adenine saturation within the same amount of time as the bbb22-23+ spirochetes. Kinetic analyses of the initial rates of adenine transport for 22distp-bbb22+ and bbb22-23+ spirochetes determined that both clones demonstrated the same Km values for adenine (0.19 μM ± 0.01 and 0.13 μM ± 0.04, respectively) (Table 3). Together, these data suggest that bbb23 alone does not contribute to adenine transport under the conditions of this assay. The bbb22 gene, when expressed under the control of the long 5′ UTR, was sufficient to restore adenine uptake to the level of bbb22-23+ spirochetes.

Cold hypoxanthine, adenine, and guanine compete with [3H]hypoxanthine for uptake by spirochetes harboring either bbb22 or bbb23 alone.

Taking advantage of the finding that spirochetes harboring bbb22 alone (22distp-bbb22+) or bbb23 alone (flaBp-bbb23+) were capable of some degree of [3H]hypoxanthine uptake (Fig. 3B), we sought to determine the ability of unlabeled hypoxanthine, adenine, and guanine to compete with this function. Consistent with our data demonstrating that bbb22 is functional to transport adenine as well as hypoxanthine, [3H]hypoxanthine transport by the 22distp-bbb22+ clone was reduced to nearly 3% and 20% in the presence of excess cold adenine and cold hypoxanthine, respectively (Fig. 4). Furthermore, bbb22 provided the spirochetes with the ability to transport guanine as [3H]hypoxanthine transport by the 22distp-bbb22+ clone was reduced to 37% in the presence of excess cold guanine. Similarly, flaBp-bbb23+ spirochetes demonstrated a reduction in [3H]hypoxanthine transport in the presence of excess cold hypoxanthine, adenine, and guanine (13%, 16% and 5%, respectively) (Fig. 4). The finding that that excess cold adenine was able to compete for [3H]hypoxanthine transport by flaBp-bbb23+ spirochetes was surprising, given that direct transport of [3H]adenine by this clone was not detected (Fig. 3B), and suggested that the low adenine transport activity conferred by bbb23 alone was detectable only when the substrate was present in high concentrations. Alternatively, it is possible that adenine is not actively transported by the flaBp-bbb23+ spirochetes and that high concentrations of adenine may interfere with the hypoxanthine transport activity of this clone. As expected based on our previous work (7), hypoxanthine transport by either of these clones was unaffected by the presence of the pyrimidine cytosine (Fig. 4). Overall, these data suggest that individually both bbb22 and bbb23 are able to provide B. burgdorferi with the ability transport to hypoxanthine, adenine, and guanine. Moreover, these data suggest a trend in which adenine is a stronger competitor than guanine for hypoxanthine transport by bbb22+ spirochetes (P = 0.06, unpaired t test) and that guanine is a stronger competitor than adenine for hypoxanthine transport by bbb23+ spirochetes (P = 0.02 unpaired t test).

FIG 4.

Adenine and guanine compete with hypoxanthine for transport by both BBB23 and BBB22 individually. [3H]hypoxanthine (0.25 μM, 20μCi) uptake by 22distp-bbb22+ and flaBp-bbb23+ spirochetes was determined at 15 min following the addition of radiolabeled purine in the absence (no competitor) or presence of 20-fold excess (5 μM) unlabeled competitor as indicated. [3H]hypoxanthine uptake by 22distp-bbb22+ or flaBp-bbb23+ spirochetes in the absence of competitor was taken as 100%. All other data are represented as the percent uptake relative to that of 22distp-bbb22+ or flaBp-bbb23+ spirochetes, respectively, in the absence of competitor. Heat-killed spirochetes served as the negative controls. Data sets were compared by an unpaired t test using GraphPad Prism, version 5.0, and relevant P values are shown.

bbb22, but not bbb23, is critical for mouse infectivity.

Together, the bbb22 and bbb23 genes are essential for B. burgdorferi infection in mice (7). We have now demonstrated that individually bbb22 and bbb23 vary in their contributions to the ability of B. burgdorferi to transport purines (Fig. 3 and 4). To investigate the individual contributions of bbb22 and bbb23 to mouse infection, mice were needle inoculated with B. burgdorferi clones bbb22-23+, Δbbb22-23/vector, 23p-bbb23+, flaBp-bbb23+, 22proxp-bbb22+, and 22distp-bbb22+ at a dose of 104 or 107 spirochetes. Mouse infection was assessed 3 weeks postinoculation by serology and spirochete reisolation from tissues. Of the mice inoculated with B. burgdorferi clones carrying bbb23 or bbb22 alone, only the mice inoculated with 22distp-bbb22+ spirochetes acquired infections (Table 3). These data suggest that bbb22 is sufficient for B. burgdorferi infection of mice whereas bbb23 is not. In support of this notion, mice infected with spirochetes harboring bbb23 alone (flaBp-bbb23+ and 23p-bbb23+) were found to be seronegative and negative for reisolation of spirochetes from tissues (Table 3), serology and reisolation of spirochetes from mouse tissues being qualitative measures of B. burgdorferi infectivity. To identify quantitative differences between the B. burgdorferi infections by 22distp-bbb22+ and bbb22-23+ spirochetes, the spirochete loads in mouse tissues inoculated with the two different clones were evaluated by quantitative PCR. Our results demonstrated that spirochete loads in the ear tissues of mice infected with the 22distp-bbb22+ clone were significantly reduced compared to the spirochete burdens in the ear tissues of mice infected with bbb22-23+ spirochetes (Fig. 5). Although no statistical difference was detected between the spirochete loads in the heart and joint tissues infected with the two clones, the data suggested a trend toward reduced spirochete numbers in the tissues of the mice infected with spirochetes harboring bbb22 alone (Fig. 5C). This analysis was also carried out for tissues harvested from mice inoculated with clones flaBp-bbb23+ and Δbbb22-23, both of which were found to be noninfectious by the qualitative measures of infection (Table 4). As expected, there was no quantitative detection of spirochetes in the tissues of mice inoculated with clones flaBp-bbb23+ and Δbbb22-23 (data not shown). Together, these data suggest that spirochetes harboring bbb22 alone are able to infect mice. However, the bbb22 gene alone is not sufficient to allow the spirochetes to maintain the level of B. burgdorferi burden in tissues achieved by spirochetes that carry both the bbb22 and bbb23 genes together.

FIG 5.

The bbb22 gene alone is not sufficient to maintain wild-type levels of spirochete loads in infected mouse tissues. DNA was isolated from ear, heart, and joint tissues of C3H/HeN mice inoculated with 1 × 104 bbb22-23+ or 22distp-bbb22+ spirochetes. Samples were analyzed for B. burgdorferi (Bb) flaB and murine nidogen DNA copies by qPCR. Each data point represents the average of triplicate measures from the DNA of an individual mouse. The mean value for each group is indicated by a horizontal line. Data sets were compared by one-way ANOVA using GraphPad Prism, version 5.0. *, P < 0.05; NS, not significant.

TABLE 4.

Spirochetes carrying bbb22 alone demonstrate qualitative measures of mouse infectivity

| Clone | Spirochete dose per mouse | Serology (no. of seropositive mice/no. of mice inoculated)a | Spirochete reisolation from tissues (no. of positive tissues/no. of mice inoculated) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ear | Bladder | Joint | |||

| bbb22-23+ | 1 × 104 | 6/6 | 6/6 | 6/6 | 6/6 |

| 1 × 107 | 6/6 | 6/6 | 6/6 | 6/6 | |

| Δbbb22-23 | 1 × 104 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 |

| 1 × 107 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | |

| 22proxp-bbb22+ | 1 × 104 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 |

| 1 × 107 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | |

| 22distp-bbb22+ | 1 × 104 | 6/6 | 6/6 | 6/6 | 6/6 |

| 1 × 107 | 6/6 | 6/6 | 6/6 | 6/6 | |

| 23p-bbb23+ | 1 × 104 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 |

| 1 × 107 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | |

| flaBp-bbb23+ | 1 × 104 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 |

| 1 × 107 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | |

Determined at 3 weeks postinoculation by positive serology against a total protein lysate of infectious B. burgdorferi strain B31 (1 × 104 spirochetes) or purified recombinant glutathione S-transferase (rGST)-P39 protein (1 × 107 spirochetes) (32).

DISCUSSION

Borrelia burgdorferi is dependent upon purine salvage from the environment for the synthesis of DNA and RNA (2, 5, 6, 23). We have previously shown that bbb22 and bbb23 encode purine permeases, which together are essential for B. burgdorferi infection in mice (7). In this study, we now demonstrate the individual contributions of bbb22 and bbb23 to purine transport and B. burgdorferi mouse infectivity. To understand the individual roles of bbb22 and bbb23, we first undertook transcriptional analysis to identify the transcription start sites for both genes. 5′ RACE analysis identified a distinct transcription start site for bbb22. Surprisingly, however, reverse transcriptase PCR analysis across the intergenic region between the annotated bbb23 and bbb22 ORFs indicated the presence of a continuous transcript across the two genes (S. Jain and M. W. Jewett, unpublished data). Together, these data suggested the possibility of an additional long bbb22 transcript that originates from either cotranscription with bbb23 or a second bbb22 transcription start site within the bbb23 ORF. Indeed, the 5′ end of a transcript was identified upstream of bbb22 within bbb23, just downstream of a promoter sequence identified in our B. burgdorferi IVET screen (21; M. W. Jewett, unpublished data), indicating that this transcript is expressed both in vitro and in vivo. The long 5′ UTR sequence produced from the bbb22 distal promoter (22distp) was found to be important for bbb22 expression as well as bbb22-dependent purine transport and murine infectivity. A long 5′ UTR was also identified upstream of the bbb23 ORF. However, the bbb22-23 trans-complementation construct carrying only 110 bp of bbb23 upstream sequence was sufficient to restore wild-type in vitro purine transport and mouse infectivity to Δbbb22-23 spirochetes under the experimental conditions tested, raising the question as to the importance of the bbb23 5′ UTR (7; this work). Regulation of genes that transport and metabolize purines has been shown to occur by riboswitch-mediated control (24, 25). For purine-sensing riboswitches, this type of regulation typically occurs through the binding of guanine or adenine to the riboswitch sequence in the long 5′ UTR sequences of the regulated genes (26). Currently, there are four known classes of purine-sensing riboswitches; however, additional classes may remain yet undiscovered (26). The extended leader sequences detected upstream of bbb22 and bbb23 suggest the possibility of a riboswitch mechanism, but bioinformatics analysis (27) of the bbb22 and bbb23 5′ UTR sequences did not identify these to be one of the four known classes of purine-sensing riboswitches. The functional roles of the 5′ UTR sequences of both bbb22 and bbb23 are under investigation.

The transcription level of the bbb23 gene in spirochetes grown to late stationary phase was found to be approximately 100-fold less than that of the bbb22 gene. This disparity in the level of expression of the two genes in late stationary phase was eliminated when the bbb23 ORF was expressed under the control of the constitutive flaB promoter. Although overexpression of bbb23 may not reflect the physiological level of bbb23 expression, genetic standardization of the bbb23 and bbb22 expression levels allowed direct comparison of in vitro transport function(s) conferred by each gene alone.

The bbb22 gene, only when expressed under the control of the distal promoter within the bbb23 ORF (22distp-bbb22+), enabled Δbbb22-23 spirochetes to take up [3H]hypoxanthine and [3H]adenine. Furthermore, [3H]hypoxanthine uptake by 22distp-bbb22+ spirochetes was inhibited by excess cold hypoxanthine and adenine as well as guanine, albeit to a lesser extent. The constitutive expression of the bbb23 gene (flaBp-bbb23+) enabled Δbbb22-23 spirochetes to take up a measurable amount of [3H]hypoxanthine but not [3H]adenine. Surprisingly, however, [3H]hypoxanthine uptake by flaBp-bbb23+ spirochetes was inhibited by excess cold hypoxanthine, adenine, and guanine. These findings suggest that bbb23 confers purine transport function; however, detection of this function in vitro was achieved only under experimental conditions where the bbb23 gene was constitutively expressed and where the amount of adenine was greater than 10 times the physiological concentration (22). These data suggest that individually both bbb22 and bbb23 are able to provide Δbbb22-23 spirochetes with the ability to transport hypoxanthine, adenine, and guanine, but the purine transport functions conferred by each gene are quantitatively distinct. Kinetic analysis revealed that there was no difference between the Km values for hypoxanthine and adenine for 22distp-bbb22+ spirochetes and spirochetes carrying both bbb22 and bbb23. In contrast, the Km values for hypoxanthine and adenine for spirochetes expressing only bbb23 (flaBp-bbb23+) were unable to be measured due to the low initial rates of hypoxanthine and adenine uptake by this clone. These data suggest that the BBB23 protein does not contribute to the affinity of the BBB23-BBB22 purine transport system for hypoxanthine and adenine. Rather, results indicate a role of bbb23 in the ability of bbb22-bbb23+ spirochetes to achieve the maximum level of hypoxanthine saturation. Because spirochetes carrying bbb22 alone demonstrated no defect in the Km value for hypoxanthine yet the level of hypoxanthine saturation for this clone was significantly reduced relative to that of bbb22-bbb23+ spirochetes, the affinity of BBB22 for hypoxanthine may be sufficient for the initial uptake of this purine, but continuous hypoxanthine uptake requires the additional activity of the lower-affinity BBB23 protein. Together, these findings demonstrate that the purine transport function encoded by the bbb22 gene alone is greater than the purine transport function encoded by the bbb23 gene alone. The bbb22 gene was sufficient to achieve wild-type levels of adenine uptake. However, neither gene alone conferred the level of hypoxanthine uptake accomplished by bbb22-23+ spirochetes, demonstrating that both genes are required to provide wild-type purine transport function.

The amino acid sequences of BBB22 and BBB23 are 78.3% identical. Nonetheless, the two proteins demonstrate distinct abilities to transport hypoxanthine, adenine, and guanine. This suggests that the differential transport functions of the two proteins may be dictated by a few key differences in amino acid residues. Recently, structure-function analyses of the E. coli adenine-specific permeases PurP and YicO and hypoxanthine-guanine-specific permeases YjcD and YgfQ as well as the A. nidulans adenine-hypoxanthine-guanine permease AzgA identified key amino acid residues critical for purine uptake activity (13, 15). Both of these studies identified an aspartic acid and a glutamic acid residue (Asp339 and Glu394 in AzgA) to be essential for the transport function for all five COG2252 family members (13, 15). These residues are conserved in BBB22 and BBB23. Strikingly, however, two key residues shown to be important for purine transport function are conserved in BBB22 but divergent in BBB23 (13, 15). Amino acid Thr275 in YjcD was found to be critical for hypoxanthine-guanine transport (13, 15). This residue is conserved in BBB22 as well as in the other COG2252 proteins (13, 15), but an isoleucine is present at this position in BBB23. In addition, Gly129 has been shown to be important for AzgA substrate binding (13, 15). This residue is conserved in BBB22 and in the E. coli adenine-specific permeases, whereas BBB23 and the E. coli hypoxanthine-guanine-specific permeases have a serine at this position (13, 15). Future mutational analysis of the BBB22 and BBB23 proteins, guided by the current understanding of the molecular interactions important for the transport activities of COG2252 family members, will provide insight into the molecular basis for the functional differences between these two highly related transporters.

Antibodies specific for the BBB22 and BBB23 proteins are not currently available. Numerous attempts to detect BBB22 and BBB23 protein production in B. burgdorferi carrying epitope-tagged bbb22 and bbb23 under the control of both native and constitutive promoters were unsuccessful (S. Jain and M. W. Jewett, unpublished data), suggesting that the amounts of BBB22 and BBB23 produced in in vitro-grown B. burgdorferi are below the levels of detection of our assay. Nonetheless, low levels of BBB22 and BBB23 protein have been detected previously through genome-wide proteomic analysis of in vitro-grown B. burgdorferi using nano-liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (28). Future studies will focus on sensitive detection of BBB22 and BBB23 using unique monoclonal antibodies to experimentally establish the cellular localization of the two proteins and determine whether the purine transport activities of these proteins involve interaction with one another and/or other yet to be identified B. burgdorferi proteins.

Of the B. burgdorferi clones carrying only bbb22 or bbb23, only 22distp-bbb22+ spirochetes demonstrated mouse infectivity as measured by serology and reisolation of spirochetes from infected tissues. This finding highlights the requirement for the bbb22 5′ UTR sequence for bbb22 function and the distinct individual capabilities of the bbb22 and bbb23 genes. Both hypoxanthine and adenine are available for salvage from the blood and tissues (22). B. burgdorferi is transiently present in the blood during the initial stages of mammalian infection and then rapidly disseminates to distal tissues (29–31). Hypoxanthine has been reported to be the most abundant purine in human plasma, at a concentration of approximately 8 μM (20). The concentration of adenine in human plasma has been found to be approximately 0.3 μM (20). The concentration of both hypoxanthine and adenine in tissues has been reported to be approximately 0.4 μM (22). We have found that the Km values for hypoxanthine and adenine for spirochetes carrying both the bbb22 and bbb23 genes are 3.4 ± 0.5 μM and 0.13 ± 0.04 μM, respectively. These Km values correlate well with the reported physiological concentrations of hypoxanthine in plasma and of adenine in plasma and tissues. Because the reported physiological concentration of hypoxanthine in tissues is 10-fold less than the Km, this suggests that following the transient blood-borne phase of dissemination of B. burgdorferi may be primarily dependent on adenine salvage to generate hypoxanthine through adenine deamination (5, 8, 9). Indeed, our findings indicate that bbb22-dependent adenine transport is essential for B. burgdorferi survival in mice. The affinity of 22distp-bbb22+ spirochetes for hypoxanthine and adenine was equivalent to that of spirochetes carrying both genes. However, the maximum amount of hypoxanthine uptake achieved by 22distp-bbb22+ spirochetes was significantly reduced compared to the amount with the bbb22-bbb23+ clone. The enzymatic conversion of adenine to hypoxanthine by adenine deaminase, AdeC, offers B. burgdorferi another source of hypoxanthine (8). Nevertheless, our data suggest that this deficiency in hypoxanthine uptake resulted in a quantitative difference in the infectious phenotype of 22distp-bbb22+ versus that of bbb22-23+ spirochetes. Tissues isolated from mice infected with 22distp-bbb22+ spirochetes demonstrated a reduced spirochete load compared to tissues isolated from mice infected with bbb22-23+ spirochetes, perhaps suggesting that the transport of maximum amounts of hypoxanthine during the initial stages of infection is important for B. burgdorferi dissemination and colonization of tissues. Although flaBp-bbb23+ spirochetes showed some ability to transport purines in vitro, the finding that flaBp-bbb23+ spirochetes are noninfectious in mice demonstrated that the purine transport affinities of spirochetes containing only bbb23 are not sufficient to support spirochete survival. The bbb23 gene is thus dispensable for B. burgdorferi survival in mice. Nonetheless, this gene is required along with bbb22 for B. burgdorferi to achieve maximal spirochete loads in infected mouse tissues.

The combined significance of the bbb22 and bbb23 genes to B. burgdorferi biology is highlighted by the fact that these genes are encoded on the essential cp26 plasmid. cp26, unlike the approximately 20 linear and circular plasmids of B. burgdorferi, is present in all natural isolates examined (23), indicating that the bbb22 and bbb23 genes are maintained across the B. burgdorferi population. All in all, these data indicate that both bbb22 and bbb23 are critical for B. burgdorferi to achieve maximal infection of mice and suggest that the differences in the patterns of expression and functional capabilities of the highly related transporters may reflect distinct purine salvage needs that the spirochete encounters throughout its natural infectious cycle.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the Jewett lab for critical reading of the manuscript, Travis Jewett and Victor Davidson for insightful comments and suggestions, and Philip Adams for technical assistance. We also thank the Nona Animal Facility animal care staff.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers K22AI081730 (M.W.J.) and R01AI099094 (M.W.J.), the National Research Fund for Tick-Borne Diseases (M.W.J.), and a UCF ORC in-house research grant (M.W.J.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Kose M, Schiedel AC. 2009. Nucleoside/nucleobase transporters: drug targets of the future? Future Med Chem 1:303–326. doi: 10.4155/fmc.09.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbour AG, Putteet-Driver AD, Bunikis J. 2005. Horizontally acquired genes for purine salvage in Borrelia spp. causing relapsing fever. Infect Immun 73:6165–6168. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.9.6165-6168.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casjens S, Palmer N, van Vugt R, Huang WM, Stevenson B, Rosa P, Lathigra R, Sutton G, Peterson J, Dodson RJ, Haft D, Hickey E, Gwinn M, White O, Fraser CM. 2000. A bacterial genome in flux: the twelve linear and nine circular extrachromosomal DNAs in an infectious isolate of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol 35:490–516. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fraser CM, Casjens S, Huang WM, Sutton GG, Clayton R, Lathigra R, White O, Ketchum KA, Dodson R, Hickey EK, Gwinn M, Dougherty B, Tomb J F, Fleischmann RD, Richardson D, Peterson J, Kerlavage AR, Quackenbush J, Salzberg S, Hanson M, van Vugt R, Palmer N, Adams MD, Gocayne J, Weidman J, Utterback T, Watthey L, McDonald L, Artiach P, Bowman C, Garland S, Fuji C, Cotton MD, Horst K, Roberts K, Hatch B, Smith HO, Venter JC. 1997. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature 390:580–586. doi: 10.1038/37551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawrence KA, Jewett MW, Rosa PA, Gherardini FC. 2009. Borrelia burgdorferi bb0426 encodes a 2′-deoxyribosyltransferase that plays a central role in purine salvage. Mol Microbiol 72:1517–1529. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06740.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pettersson J, Schrumpf ME, Raffel SJ, Porcella SF, Guyard C, Lawrence K, Gherardini FC, Schwan TG. 2007. Purine salvage pathways among Borrelia species. Infect Immun 75:3877–3884. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00199-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain S, Sutchu S, Rosa PA, Byram R, Jewett MW. 2012. Borrelia burgdorferi harbors a transport system essential for purine salvage and mammalian infection. Infect Immun 80:3086–3093. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00514-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jewett MW, Lawrence K, Bestor AC, Tilly K, Grimm D, Shaw P, VanRaden M, Gherardini F, Rosa PA. 2007. The critical role of the linear plasmid lp36 in the infectious cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol 64:1358–1374. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05746.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jewett MW, Lawrence KA, Bestor A, Byram R, Gherardini F, Rosa PA. 2009. GuaA and GuaB are essential for Borrelia burgdorferi survival in the tick-mouse infection cycle. J Bacteriol 191:6231–6241. doi: 10.1128/JB.00450-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cecchetto G, Amillis S, Diallinas G, Scazzocchio C, Drevet C. 2004. The AzgA purine transporter of Aspergillus nidulans. Characterization of a protein belonging to a new phylogenetic cluster. J Biol Chem 279:3132–3141. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308826200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goudela S, Tsilivi H, Diallinas G. 2006. Comparative kinetic analysis of AzgA and Fcy21p, prototypes of the two major fungal hypoxanthine-adenine-guanine transporter families. Mol Membr Biol 23:291–303. doi: 10.1080/09687860600685109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kozmin SG, Stepchenkova EI, Chow SC, Schaaper RM. 2013. A critical role for the putative NCS2 nucleobase permease YjcD in the sensitivity of Escherichia coli to cytotoxic and mutagenic purine analogs. mBio 4:e00661-13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00661-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krypotou E, Diallinas G. 2014. Transport assays in filamentous fungi: kinetic characterization of the UapC purine transporter of Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal Genet Biol 63:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mansfield TA, Schultes NP, Mourad GS. 2009. AtAzg1 and AtAzg2 comprise a novel family of purine transporters in Arabidopsis. FEBS Lett 583:481–486. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papakostas K, Botou M, Frillingos S. 2013. Functional identification of the hypoxanthine/guanine transporters YjcD and YgfQ and the adenine transporters PurP and YicO of Escherichia coli K-12. J Biol Chem 288:36827–36840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.523340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saxild HH, Brunstedt K, Nielsen KI, Jarmer H, Nygaard P. 2001. Definition of the Bacillus subtilis PurR operator using genetic and bioinformatic tools and expansion of the PurR regulon with glyA, guaC, pbuG, xpt-pbuX, yqhZ-folD, and pbuO. J Bacteriol 183:6175–6183. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.21.6175-6183.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beaman TC, Hitchins AD, Ochi K, Vasantha N, Endo T, Freese E. 1983. Specificity and control of uptake of purines and other compounds in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 156:1107–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elias AF, Stewart PE, Grimm D, Caimano MJ, Eggers CH, Tilly K, Bono JL, Akins DR, Radolf JD, Schwan TG, Rosa P. 2002. Clonal polymorphism of Borrelia burgdorferi strain B31 MI: implications for mutagenesis in an infectious strain background. Infect Immun 70:2139–2150. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.2139-2150.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eells JT, Spector R. 1983. Determination of ribonucleosides, deoxyribonucleosides, and purine and pyrimidine bases in adult rabbit cerebrospinal fluid and plasma. Neurochem Res 8:1307–1320. doi: 10.1007/BF00964000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hartwick RA, Assenza SP, Brown PR. 1979. Identification and quantitation of nucleosides, bases and other UV-absorbing compounds in serum, using reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. I. Chromatographic methodology. J Chromatogr 186:647–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellis TC, Jain S, Linowski AK, Rike K, Bestor A, Rosa PA, Halpern M, Kurhanewicz S, Jewett MW. 2013. In vivo expression technology identifies a novel virulence factor critical for Borrelia burgdorferi persistence in mice. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003567. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Traut TW. 1994. Physiological concentrations of purines and pyrimidines. Mol Cell Biochem 140:1–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00928361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jewett MW, Byram R, Bestor A, Tilly K, Lawrence K, Burtnick MN, Gherardini F, Rosa PA. 2007. Genetic basis for retention of a critical virulence plasmid of Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol 66:975–990. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05969.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mandal M, Boese B, Barrick JE, Winkler WC, Breaker RR. 2003. Riboswitches control fundamental biochemical pathways in Bacillus subtilis and other bacteria. Cell 113:577–586. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00391-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mandal M, Breaker RR. 2004. Adenine riboswitches and gene activation by disruption of a transcription terminator. Nat Struct Mol Biol 11:29–35. doi: 10.1038/nsmb710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim JN, Breaker RR. 2008. Purine sensing by riboswitches. Biol Cell 100:1–11. doi: 10.1042/BC20070088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang TH, Huang HD, Wu LC, Yeh CT, Liu BJ, Horng JT. 2009. Computational identification of riboswitches based on RNA conserved functional sequences and conformations. RNA 15:1426–1430. doi: 10.1261/rna.1623809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Angel TE, Luft BJ, Yang X, Nicora CD, Camp DG II, Jacobs JM, Smith RD. 2010. Proteome analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi response to environmental change. PLoS One 5:e13800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dolan MC, Piesman J, Schneider BS, Schriefer M, Brandt K, Zeidner NS. 2004. Comparison of disseminated and nondisseminated strains of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto in mice naturally infected by tick bite. Infect Immun 72:5262–5266. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5262-5266.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liveris D, Schwartz I, Bittker S, Cooper D, Iyer R, Cox ME, Wormser GP. 2011. Improving the yield of blood cultures from patients with early Lyme disease. J Clin Microbiol 49:2166–2168. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00350-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rego RO, Bestor A, Stefka J, Rosa PA. 2014. Population bottlenecks during the infectious cycle of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. PLoS One 9:e101009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Halpern MD, Molins CR, Schriefer M, Jewett MW. 2014. Simple objective detection of human Lyme disease infection using immuno-PCR and a single recombinant hybrid antigen. Clin Vaccine Immunol 21:1094–1105. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00245-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]