Abstract

Objectives: This open-label, prospective, phase I/II trial was performed to establish the safety and efficacy of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) herbal products for treating non–anemia-related fatigue in patients with cancer. Although this practice is widespread in China, it has not been confirmed in a prospective clinical study.

Design: Thirty-three patients who had completed cancer treatment, had stable disease and no anemia, and reported moderate to severe fatigue (rated ≥4 on a 0–10 scale) were enrolled in a TCM outpatient clinic. Patients took Ren Shen Yangrong Tang (RSYRT) decoction, a soup containing 12 TCM herbs, twice a day for 6 weeks. RSYRT aims to correct qi deficiency. Fatigue was assessed before and after RSYRT therapy, which all patients completed.

Results: No discomfort or toxicity was observed. Before the study, all patients had had fatigue for at least 4 months. Fatigue severity decreased significantly from before therapy to 6 weeks after therapy: from 7.06 to 3.30 on a 0–10 scale (p<0.001). Fatigue category (mild, moderate, severe) shifted significantly (p=0.024): Of 22 patients with severe fatigue (rated ≥7) before therapy, 11 had mild fatigue and 11 had moderate fatigue after TCM treatment. The time-to-fatigue-alleviation was 2–3 weeks.

Conclusion: RSYRT therapy was safe and was associated with fatigue improvement in nonanemic cancer survivors, consistent with historical TCM clinical practice experience. Because of a possible placebo effect in this open-label study, decoction RSYRT warrants further study in randomized clinical trials to confirm its effectiveness for managing moderate to severe fatigue.

Introduction

The difficulty of managing fatigue in cancer patients and survivors has been recognized as a major challenge in oncology care.1–3 Fatigue was the most prevalent symptom reported in a quantitative study of multiple symptoms in Chinese cancer patients and survivors, 25% of whom had severe fatigue.4 In Western countries, interventions for fatigue in the past have centered on direct management of anemia or other comorbidities, physical exercise, sleep training, neurostimulants, and antidepressants. These interventions are rarely used in China; instead, the most common approach to fatigue management, as part of a holistic regimen, has been self-referral or professional referral to Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). However, no clinical study has examined the effectiveness and toxicities of these raw herbal medicines.

According to TCM theory, qi refers to the energy flow of the body (or a physical life force), which maintains blood circulation, warms the body, and fights disease.5 Fatigue is characterized by a deficiency in qi6 that may be accompanied by fatigue/tiredness, shortness of breath, reduced activity, poor sleep, and/or poor appetite. For hundreds of years, Ren Shen Yangrong Tang (RSYRT) has been used to manage symptoms by improving qi deficiency. RSYRT was originally described in the classic TCM book, Taiping Huimin Heji Ju Fang (Formulas of Taiping Pharmaceutical Bureau for Benevolence), first published in 1078 during the Song Dynasty.7 RSYRT is composed of 12 different herbs, of which ginseng (often replaced by dangshen in current TCM practice) and huangqi are the backbone components. Despite its long use, the safety, effect, common dosage, and production of or reduction in symptoms associated with RSYRT have not been investigated in a prospective clinical study.

Therefore, a pilot RSYRT intervention study was conducted in cancer survivors with moderate to severe fatigue. Patient-reported fatigue severity was measured by using the validated Chinese version of a multisymptom scale that included a fatigue item. The study hypothesis was that promising preliminary evidence of the efficacy and safety of this combination of herbs could lead to further randomized investigations.

Materials and Methods

Patient sample and data collection

This was an open-label, noncontrolled phase I/II study. Patients with cancer who visited a TCM clinic in a tertiary cancer hospital in Beijing between June 2006 and October 2008 were enrolled. Eligible patients had a pathologically confirmed cancer diagnosis, had been off active therapy for at least 1 month, had moderate to severe fatigue (rated ≥4 on a 0–10 scale), had no evidence of disease or were in stable condition, were not anemic (hemoglobin ≥10 g/dL), and had not used TCM medications in the past 2 months but were willing to try them. Patients with estrogen receptor–positive or progesterone receptor–positive breast cancer were excluded.

Fatigue screening was performed before enrollment. Patients rated their fatigue severity on the single item “fatigue at its worst” from the Chinese-language version of the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI-C), a validated multisymptom assessment tool.8 MDASI-C symptom items are rated on a 0–10 scale, where 0=“not present” and 10=“as bad as you can imagine.” A second fatigue assessment was completed at the end of the 6-week study.

Data collected by research staff included sex, age, diagnosis, cancer stage, date of completion of cancer therapy, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, and duration of fatigue. Patients were required to return to the TCM clinic for follow-up every 2 weeks during the 6-week study. In qualitative interviews at each follow-up visit, study staff documented toxicities, the patient's feelings of fatigue relief, and adherence to study medication during the trial. Electrocardiograms and blood counts were examined before and after TCM therapy.

The institutional review board of Beijing Cancer Hospital & Institute, Beijing, China, approved this study. All patients provided informed consent.

TCM evaluation and therapy

At the beginning and end of the study, all patients received a TCM evaluation by a TCM doctor. This evaluation is known as bian zheng, meaning the differentiation of symptoms and signs on the basis of TCM theory.9 The outcomes of this evaluation, including pulse rate, the patient's description of any symptoms, and the color and shape of the tongue, were documented.

The classic formula of RSYRT in Taiping Huimin Heji Ju Fang is a combination of 12 herbal products. See Table 1 for a review of each herb;10,11 note that current practice in China is to replace ginseng with dangshen for RSYRT because dangshen is easier to find and less expensive than ginseng, yet has similar clinical effect. The herbal RSYRT preparation was manufactured (ChongGuanYaoYe, Beijing, China), packaged, and labeled in compliance with standard national manufacturing practice for quality control. Patients received the combination of herbs from the hospital pharmacy and made the decoction by slow cooking in 150 mL of water, according to the pharmacy's preparation directions. Dosages of these herbs for this trial were in the safe range according to the Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China (Chinese Pharmacopoeia).12 All qualified patients were asked to take the RSYRT decoction twice per day (in the morning and in the evening) for 6 continuous weeks. The core formula was adjusted for specific patients, according to bian zheng.

Table 1.

Components of Ren Shen Yangrong Tang ( RSYRT)

RSYRT)

| Name | TCM treatment | Typical dose | Extraction | Preclinical study (Li 2006, 10 Fang 199811) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Dangshen (Radixcodonopsis pilosulae; root of pilose asiabell; often replaces ginseng)

|

Strengthen spleen and tonify lung | 10–30 g | Synanthrin | Enhance immunologic function |

Huanqi (Astragalus mongholicus)

|

Supplement qi | 10–30 g | Huangqi polysaccharose | Tumor inhibition Immunomodulatory effects |

Baizhu (Rhizoma atractylodes macrocephala; white rhizome of largehead atractylodes)

|

Fortify the spleen and boost qi | 5–15 g | Volatile oil (Cangzhu ketone) | Enhance immunologic function |

Fuling (Poria cocos; Indian bread)

|

Fortify the spleen and disinhibit water | 9–15 g | Polysaccharide | Antitumor |

Chenpi (Pericarpium citri reticulatae; dried tangerine peel)

|

Fortify the spleen and transform phlegm | 3–9 g | Volatile oil Hesperidin | Anti-inflammatory Antioxygenation |

Shengdi (Radix rehmanniae; root of rehmannia)

|

Clear heat and cool the blood | 10–30 g | Radix rehmanniae extract Provitamin A | Antiaging |

Baishao (Radix paeoniae alba; white peony root)

|

Nourish the blood and emolliate the liver | 6–15 g | Total glucosides of peony | Enhance immunologic function Analgesia |

Danggui (Angelica sinensis; root of Chinese Angelica)

|

Supplement the blood and regulate menstruation | 5–15 g | Volatile oil Ligustilide | Promote hematopoietic function |

Wuweizi (Fructus schisandrae; shizandra berry)

|

Constrain the lung and enrich the kidney | 3–10 g | Schizandrin | Liver protection Enhance immunologic function |

Yuanzhi (Radix polygalae; polygala root)

|

Quiet the heart and the spirit | 3–10 g | Yuanzhi saponins | Mitigation function |

Rougui (Cortex cinnamomi; cinnamon)

|

Tonify fire and help yang | 2–6 g | Cinnamic acid ester | Promote biliation |

Gancao (Radix glycyrrhizae; licorice)

|

Supplement the center and boost qi | 2–10 g | Glycyrrhizin | Enhance immunologic function |

TCM, Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Statistical analysis

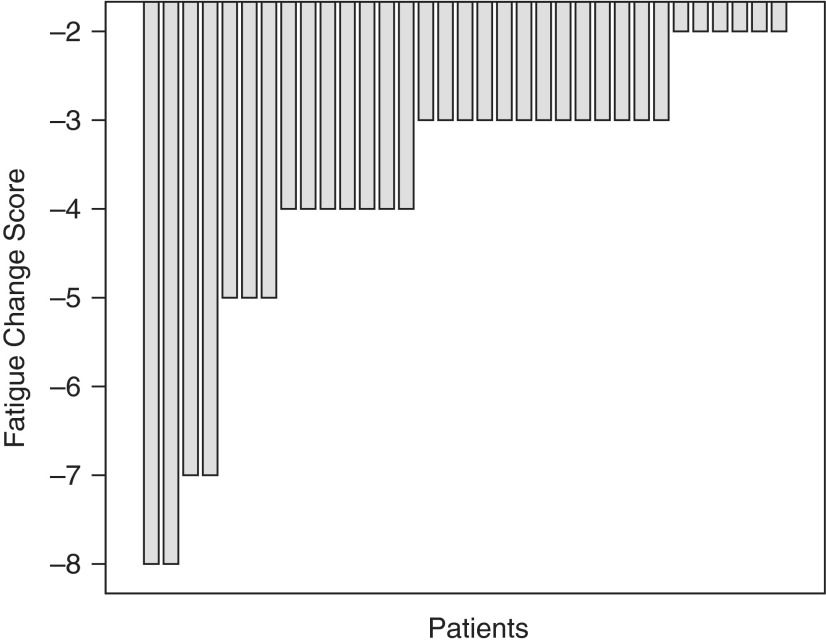

The primary outcome of the study was change in the patient-reported fatigue ratings between the beginning and end of the study. The secondary outcome was the patient-reported time to fatigue alleviation after beginning RSYRT. The fatigue cut-points for mild (≥1), moderate (≥4), and severe (≥7) fatigue on the 0–10 scale were based on National Comprehensive Cancer Network fatigue practice guidelines.13 Fatigue category (mild, moderate, or severe) was analyzed as ranked data in a nonparametric test (McNemar test). The difference in fatigue ratings before and after 6 weeks of therapy was examined by paired t-test. A waterfall plot was constructed to illustrate treatment efficacy for individual patients. All statistical procedures were performed by using the SPSS Statistical Software Program for Windows, version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). All p-values reported are two tailed. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

Table 2 presents the demographic and disease-related characteristics for this sample (n=33). At enrollment, 32 of 33 patients were at least 3 months past their cancer therapy (surgery, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy); the remaining patient was 1.5 months postsurgery. Although 39% of the sample had late-stage cancer, 60% of all patients had good functional status (ECOG performance status of 0). The prescreening of fatigue severity showed that a third of sample (n=11) had moderate fatigue (rated 4–6 on the 0–10 scale) before commencing TCM therapy, and the remainder (n=22) had severe fatigue (rated 7–10 on the 0–10 scale). All patients reported having felt fatigued for at least 4 months.

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics (n=33)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Median age (y) | 60 (41–81) |

| Mean duration of fatigue (mo) | 4.2 (1.5–11.0) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 14 (42) |

| Female | 19 (58) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Colorectal cancer | 7 (21.2) |

| Lung cancer | 6 (18.2) |

| Breast cancer (ER, PR negative) | 6 (18.2) |

| Gastric cancer | 5 (15.15) |

| Lymphoma | 4 (12.1) |

| Other | 5 (15.15) |

| Cancer stage, n (%) | |

| II | 12 (36.4) |

| III | 8 (24.2) |

| IV | 13 (39.4) |

| Baseline ECOG performance status score, n (%) | |

| 0 | 21 (63.6) |

| 1 | 11 (33.3) |

| 2 | 1 (3.0) |

Median values are expressed with ranges in parentheses.

ER, estrogen receptor positive; PR, progesterone receptor-positive; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Toxicity of and adherence to TCM therapy

The RSYRT formula was adjusted for specific patients on the basis of the individual's TCM evaluation: 25 patients with deficiency of lung qi were given an increased dose of chenpi, wuweizi, and gancao; 6 patients with blood deficiency were given an increased dose of danggui; and rougui was removed from the core formula for 2 patients with yin deficiency.

During the trial, no patient reported an uncomfortable event. Clinicians documented no gastrointestinal upset, insomnia, diarrhea, headache, sweating, rash, or other symptoms. Adherence to the TCM trial agent was excellent, with all patients reporting that they used the RSYRT decoction twice a day. No patients required a dose reduction or dose interruption because of poor tolerance of the decoction, nor did any patient withdraw from the study.

Laboratory results showed no abnormal routine blood chemistry values or liver or kidney function results, either before or after TCM therapy. Electrocardiogram results for 2 patients were abnormal (change in ST segment) before TCM therapy but were normal after treatment. ECOG performance status did not significantly change from pretherapy to posttherapy.

Fatigue and TCM outcome evaluation

All patients contributed MDASI-C symptom data before and after TCM therapy. A significant reduction in mean fatigue severity was seen from before therapy (mean±standard deviation, 7.06±1.29) to after 6 weeks of therapy (3.30±1.36) (p<0.001).

Fatigue category (mild, moderate, or severe) shifted significantly (p=0.024) during the study. Of 11 patients with moderate fatigue before the intervention, 10 had mild fatigue and 1 still had moderate fatigue at the end of the study; likewise, of 22 patients with severe fatigue before therapy, 11 had mild fatigue and 11 had moderate fatigue after therapy. The individual reductions in patient-reported fatigue severity (rated on the MDASI-C 0–10 scale) from pretreatment to posttreatment are shown on a waterfall plot (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Change in fatigue severity after treatment with Ren Shen Yangrong Tang (RSYRT). Patients rated fatigue on a 0–10 scale before and after RSYRT therapy. The waterfall plot shows that every patient reported reduced fatigue severity compared with his or her pretherapy score.

For time to fatigue alleviation after beginning RSYRT, qualitative follow-up reports indicated that all 33 patients had self-appraised improvement within 4 weeks of commencing TCM therapy. Twenty-one patients (64%) felt much better within 2 weeks, 11 (33%) felt better after 3 weeks, and 1 felt better after 4 weeks.

Table 3 shows the TCM evaluation outcomes before the first dose of RSYRT intervention. Most patients reported other symptoms as well, which according to bian zheng are related to three subtypes of qi deficiency: lung-qi deficiency, blood deficiency, or yin deficiency. Fatigue severity did not significantly differ among these three deficiency subtypes. Subtypes did not change after therapy, with all patients showing qi deficiency as a major complaint of fatigue or tiredness. Many of the baseline symptoms improved, including disturbed sleep, dry mouth, drowsiness, and poor appetite.

Table 3.

Preintervention Traditional Chinese Medicine Evaluation (n=33)

| Type of bian zheng | Outcomes by TCM measures | Patients, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Main characteristic | ||

| Qi deficiency | Shortness of breath, fatigue and weakness, pale tongue with white coating, small and weak pulse | 33 (100) |

| Secondary characteristics | ||

| Lung-qi deficiency | Shortness of breath, taciturnity, white coating on tongue, small and weak pulse | 25 (75.8) |

| Blood deficiency | Weakness, heart palpitation, dizziness, pale complexion, deep and/or thready pulse | 6 (18.1) |

| Yin deficiency | Dry mouth, red tongue without a cover, heat in hands and feet, deep and/or thready pulse | 2 (6.1) |

Discussion

This phase I/II, open-label, noncontrolled study evaluated a TCM therapy, RSYRT decoction, to manage fatigue in Chinese cancer survivors with stable disease. As measured by a validated patient-reported symptom outcome instrument, the Chinese language version of the MDASI (MDASI-C), fatigue was significantly reduced after 6 weeks of TCM intervention. Given the excellent tolerability and safety of RSYRT and these promising fatigue-reduction results, the RSYRT decoction warrants further examination in a randomized trial, which would eliminate any placebo effect that may have resulted from the open-label approach in the current study.

Qualitative interviewing showed that two thirds of patients experienced satisfactory fatigue relief within 2 weeks of RSYRT administration and that most of the other patients experienced relief within 3 weeks. These results suggest that 2–3 weeks is a good study length for future trials seeking to detect effective fatigue reduction with a TCM decoction, such as RSYRT.

Originally found in Taiping Huimin Heji Ju Fang, a book with a 1000-year history of adoption in holistic health care, RSYRT consists of 12 herbs (Table 1). Animal studies and human studies have shown that most herbs in this decoction, and especially the anti-inflammatory compounds derived naturally from these herbal products, strengthen the immune system.14 Although evidence supporting the inflammatory-mechanism hypothesis of symptom production is increasing, the mechanism underlying cancer-related fatigue is not clear.15 Fatigue management is difficult in oncology patient care, both for patients being actively treated and for cancer survivors. Despite the possibility of placebo effect (especially in patients with worse symptoms at baseline) in clinical trials of fatigue treatment,16 theory-driven individualized TCM practice appears to be a highly plausible treatment method, with integral control of the body plus pharmacologic effects that nonetheless need to be well defined.

A recent study in patients with breast cancer demonstrated that cancer-related fatigue and its related symptoms were significantly associated with qi deficiency as assessed by TCM theory.6 The principle of treating deficiency is called tonification, where the focus is on nourishing qi and blood (which is the source of qi). All 33 patients in this study showed qi deficiency, according to bian zheng. In the decoction RSYRT, the main effects of dangshen (or ginseng, which has a similar effect), huangqi, baizhu, fuling, chenpi, and gancao are to replenish qi and invigorate the spleen. Shengdi, danggui, and baishao are used to nourish blood. Wuweizi and yuanzhi can calm the heart and tranquilize the spirit, which should alleviate the symptoms of insomnia and palpitations. Individualized medicine, presented in this study as a slightly altered dose or change in herbs, is one significant characteristic of TCM practice that takes into account individual differences in bian zheng (the subtypes shown in Table 3) and other symptoms. This study shows that small variations in the RSYRT decoction achieved an expected consistency in addressing the main characteristic of fatigue, qi deficiency. Using a relatively fixed TCM formula with a combination of herbs rather than a single herb is based on the TCM theory of the entire human system as an object in which symptoms are driven by maladjustments in the body.17 More significant synergistic effects on symptom control have been observed with all the ingredients combined.18

TCM methods for managing chronic fatigue have been widely adopted for the treatment of cancer and other conditions in China and elsewhere.19–24 In oncology care, the TCM method most often used in China is a mixture of herbal compounds and decoction. McCulloch et al.,25 in a multilingual literature review and meta-analysis, reported that Astragalus mongholicus (huangqi)–based herbal medicine was associated with a trend (unconfirmed because of the quality of the study) of increased survival, tumor response, and performance status. Wisconsin ginseng (Panex quinquefolius) improved cancer-related fatigue in a phase III double-blind multicenter study, suggesting that a single herb can be used for effective fatigue management in certain patients.26 In Western countries, some promising natural agents have been investigated for cancer prevention or symptom control;27 however, although discussion about using TCM to manage cancer treatment-related toxicities is increasing,17,28 there is concern over the lack of well-designed clinical studies demonstrating the proven efficacy and safety of individualized herbal therapy based on TCM theory.19,29,30

Patients reported other symptoms besides fatigue, including disturbed sleep, dry mouth, drowsiness, and poor appetite, which is consistent with symptom research findings that moderate to severe fatigue often appears alongside other significant symptoms.3 Such evidence of the efficacy of an intervention in reducing multiple symptoms presents hope for relieving fatigue in patients with cancer. This is another reason for individualized alteration of the herbal mixture of RSYRT, by slightly changing the dose of the core or adding an additional herb.

The quality and safety of Chinese herbal medicines have attracted increased global attention in recent years, given that a large population uses TCM products.31,32 The 12 herbs used in RSYRT have been examined for toxicity and for the recommended regular dose of each medicinal herb, with the results recorded in the latest issue of the Chinese Pharmacopoeia.33,34 None of the 12 RSYRT herbs are among the 59 herb-derived products that are classified in that publication as having toxic effects. All are commercially available in the pharmacies of medical institutions in China.

This study had several limitations. First, because of the lack of safety information based on phase I studies of this combination decoction, an open-label design was used for this study. The possibility of placebo effect and a resulting bias toward belief in effective symptom reduction can be significant in such a nonrandomized study. Second, this study deviated from the typical clinical-trial approach in that, although the usual dose of each herb (according to safety and effectiveness guidelines in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia) was given generally, doses were slightly adjusted individually per the outcomes of bian zheng, a TCM diagnostic method. As a result, a few herbs were added or deleted from the core 12-herb RSYRT formula for certain patients. This unusual practice rarely happens in classic phase I drug trials for dosage and tolerance discovery, but it is usual in TCM practice because of its nature as an individualized medicine. In any case, the fact that no toxicity was documented in this pilot study is consistent with years of clinical experience in which this formula has been used to treat chronic disease. Finally, it would have been beneficial to have more frequent assessment (such as weekly) during the trial and to have used the multisymptom MDASI-C to quantitatively measure incremental change in fatigue and other symptoms, rather than to rely on qualitative data collection. Even so, a pilot study to develop a MDASI-TCM module4 has paved the way for using a validated patient-reported outcome tool in future TCM clinical research.

In conclusion, good feasibility and no toxicity from RSYRT decoction were observed in 33 cancer survivors who had non–anemia-related fatigue that lasted for several months. Using a well-validated patient-reported symptom outcome measure and qualitative documentation, this study obtained a preliminary impression of positive fatigue reduction from this formula. The study suggests the need for additional randomized clinical study of RSYRT to confirm true evidence of symptom control in patients with fatigue.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the editorial assistance of Jeanie F. Woodruff, BS, ELS. This study was supported by grants from Key Program Foundation of Beijing Administration of TCM to Dr. Li and by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health, including NCI P01 CA124787 to Dr. Charles Cleeland and MD Anderson Cancer Center Support grant NCI P30 CA016672. Neither the NCI nor the National Institutes of Health had any role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or preparation of the report.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Barsevick AM, Cleeland CS, Manning DC, et al. ASCPRO recommendations for the assessment of fatigue as an outcome in clinical trials. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;39:1086–1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shi Q, Smith TG, Michonski JD, et al. Symptom burden in cancer survivors 1 year after diagnosis: a report From the American Cancer Society's Studies of Cancer Survivors. Cancer 2011;117:2779–2790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang XS, Shi Q, Shah N, et al. Inflammatory markers and development of symptom burden in patients with multiple myeloma during autologous stem cell transplantation. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20:1366–1374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao Y, Liu J-W, Wang XS, Li P-P. Exploration of symptom inventory about tumor and traditional Chinese medicine [in Chinese]. Chin J Cancer Prev Treat 2008;15:861–863 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu CH, Lee CJ, Chien TJ, et al. The relationship between Qi deficiency, cancer-related fatigue and quality of life in cancer patients. J Tradit Complement Med 2012;2:129–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chien TJ, Song YL, Lin CP, Hsu CH. The correlation of traditional Chinese medicine deficiency syndromes, cancer related fatigue, and quality of life in breast cancer patients. J Tradit Complement Med 2012;2:204–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taiping Benevolent Dispensary Bureau. Song Dynasty [in Chinese]. Baidu. 2014. Online document at: http://baike.baidu.com/view/576056.htm. Accessed April 9, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang XS, Wang Y, Guo H, et al. Chinese version of the M. D. Anderson Symptom Inventory: validation and application of symptom measurement in cancer patients. Cancer 2004;101:1890–1901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yin HH, Zhang B. Basic Theory of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Shanghai, China: Shanghai Science and Technology Press, 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li L. Manual of Pharmacology and Clinical Application for Traditional Chinese Medicine. Beijing, China: People's Health Press, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fang WX. Medical Pharmacology of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Beijing, China: People's Health Press, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission. TLC Atlas of Chinese Crude Drugs in Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China. Beijing, China: People's Medical Publishing House, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mock V, Atkinson A, Barsevick A, et al. NCCN Practice Guidelines for Cancer-Related Fatigue. Oncology (Williston Park) 2000;14:151–161 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Q, Kuang H, Su Y, et al. Naturally derived anti-inflammatory compounds from Chinese medicinal plants. J Ethnopharmacol 2013;146:9–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang XS. Pathophysiology of cancer-related fatigue. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2008;12:11–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de la Cruz M, Hui D, Parsons HA, Bruera E. Placebo and nocebo effects in randomized double-blind clinical trials of agents for the therapy for fatigue in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer 2010;116:766–774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang WY. Therapeutic wisdom in traditional Chinese medicine: a perspective from modern science. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2005;26:558–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lo LC, Chen CY, Chen ST, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of traditional Chinese medicine, Shen-Mai San, in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy or radiotherapy: study protocol for a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Trials 2012;13:232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adams D, Wu T, Yang X, et al. Traditional Chinese medicinal herbs for the treatment of idiopathic chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;CD006348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao LM, Hu ZC. Clinical analysis on senile dementia treated by ginseng tonic decoction. J Pract Tradit Chin Med 2008;24:265 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen R, Moriya J, Yamakawa J, et al. Traditional Chinese medicine for chronic fatigue syndrome. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2010;7:3–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hyodo I, Amano N, Eguchi K, et al. Nationwide survey on complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients in Japan. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:2645–2654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang TF, Xue XL, Zhang YJ, et al. Effects of Xiaopi Yishen herbal extract granules in treatment of fatigue-predominant subhealth due to liver-qi stagnation and spleen-qi deficiency: a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled and double-blind clinical trial [in Chinese]. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao 2011;9:515–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yin Y-T, Xu P, Jiang GX. Ginseng yangrong soup's effect: study of chemotherapy drugs causing leucopenia. Chin Arch Tradit Chin Med 2008;26:2500–2501 [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCulloch M, See C, Shu XJ, et al. Astragalus-based Chinese herbs and platinum-based chemotherapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:419–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barton DL, Liu H, Dakhil SR, et al. Wisconsin ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) to improve cancer-related fatigue: a randomized, double-blind trial, N07C2. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013;105:1230–1238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin H, Liu J, Zhang Y. Developments in cancer prevention and treatment using traditional Chinese medicine. Front Med 2011;5:127–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cho WC. Scientific evidence on the supportive cancer care with Chinese medicine. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi 2010;13:190–194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams D, Wu T, Yasui Y, et al. Systematic reviews of TCM trials: how does inclusion of Chinese trials affect outcome? J Evid Based Med 2012;5:89–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang M, Liu X, Li J, et al. Chinese medicinal herbs to treat the side-effects of chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;CD004921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hosbach I, Neeb G, Hager S, et al. In defence of traditional Chinese herbal medicine. Anaesthesia 2003;58:282–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang J, van der Heijden R, Spruit S, et al. Quality and safety of Chinese herbal medicines guided by a systems biology perspective. J Ethnopharmacol 2009;126:31–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission. Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China. Beijing, China: People's Medical Publishing House, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ji HY, Chen XY, Jiao YZ, Tong XL. Analysis on dosage of traditional Chinese medicine decoction pieces stipulated in Chinese pharmacopoeia [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2013;38:1095–1097 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]