Abstract

Objective: We investigated whether disturbance of calcium and phosphate metabolism is associated with the presence and severity of calcific aortic valve disease (CAVD) in patients with normal or mildly impaired renal function. Methods: We measured serum levels of calcium, phosphate, alkaline phosphatase (AKP), intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH), 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25-OHD), and biomarkers of bone turnover in 260 consecutive patients with normal or mildly impaired renal function and aortic valve sclerosis (AVSc) (n=164) or stenosis (AVS) (n=96) and in 164 age- and gender-matched controls. Logistic regression models were used to determine the association of mineral metabolism parameters with the presence and severity of CAVD. Results: Stepwise increases were observed in serum levels of calcium, phosphate, AKP, and iPTH from the control group to patients with AVS, and with reverse changes for 25-OHD levels (all P<0.001). Similarly, osteocalcin, procollagen I N-terminal peptide, and β-isomerized type I collagen C-telopeptide breakdown products were significantly increased stepwise from the control group to patients with AVS (all P<0.001). In patients with AVS, serum levels of iPTH were positively, in contrast 25-OHD levels were negatively, related to trans-aortic peak flow velocity and mean pressure gradient. After adjusting for relevant confounding variables, increased serum levels of calcium, phosphate, AKP, and iPTH and reduced serum levels of 25-OHD were independently associated with the presence and severity of CAVD. Conclusions: This study suggests an association between mineral metabolism disturbance and the presence and severity of CAVD in patients with normal or mildly impaired renal function. Abnormal bone turnover may be a potential mechanism.

Keywords: Valve heart disease, Aortic stenosis, Mineral metabolism, Calcium, Phosphate

1. Introduction

Calcific aortic valve disease (CAVD), ranging from mild thickening of the cusp (i.e. aortic valve sclerosis (AVSc)) to severe aortic valve stenosis (AVS) with functional impairment, is a common acquired valvular disorder in the elderly, associated with significant morbidity and mortality (Freeman and Otto, 2005). The prevalence of AVSc without obstruction of the left ventricular outflow tract is approximately 30% in adults aged over 65 years and about 50% in those beyond 85 years, whereas significant AVS is present in 2%–7% of adults over 65 years of age (Iung et al., 2003). CAVD was once described as a passive degenerative and unmodifiable process. Thus, surgical valve replacement and transcatheter aortic valve implantation are considered to be the only established therapy for patients with severe symptomatic AVS. Recently, growing evidence demonstrates that CAVD also develops through an inflammatory process similar to atherosclerosis that can be possibly targeted with medical treatment (Rajamannan, 2009; Yetkin and Waltenberger, 2009). Unfortunately, several randomized, placebo-control trials have failed to show that use of statins retards the progression of AVS (Parolari et al., 2011; Teo et al., 2011), suggesting that despite similar risk factors and downstream mediators, atherogenesis is not pivotal to the pathogenesis of CAVD. Therefore, a strong impulse is emerging to further investigate the novel pathophysiological pathways and their modulation in order to prevent/delay the onset or progression of valve degeneration (Rajamannan et al., 2011). Disturbance of mineral metabolism has been proposed as a potential etiology for aortic valve calcification in end-stage renal disease, malignancy, sarcoidosis, or hyperparathyroidism (Strickberger et al., 1987; Stefenelli et al., 1993; Kume et al., 2006; Iwata et al., 2013). However, its role in the development of CAVD for patients with relatively preserved renal function remains largely unknown. In this pair-matched case-control study, we sought to test the hypothesis that abnormal calcium and phosphate metabolism is associated with the presence and severity of CAVD in patients with normal or mildly impaired renal function. In addition, serum levels of bone turnover biomarkers, including osteocalcin, procollagen I N-terminal peptide (PINP), and β-isomerized type I collagen C-telopeptide breakdown products (β-CTx), were measured to elucidate the possible mechanisms.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patient population

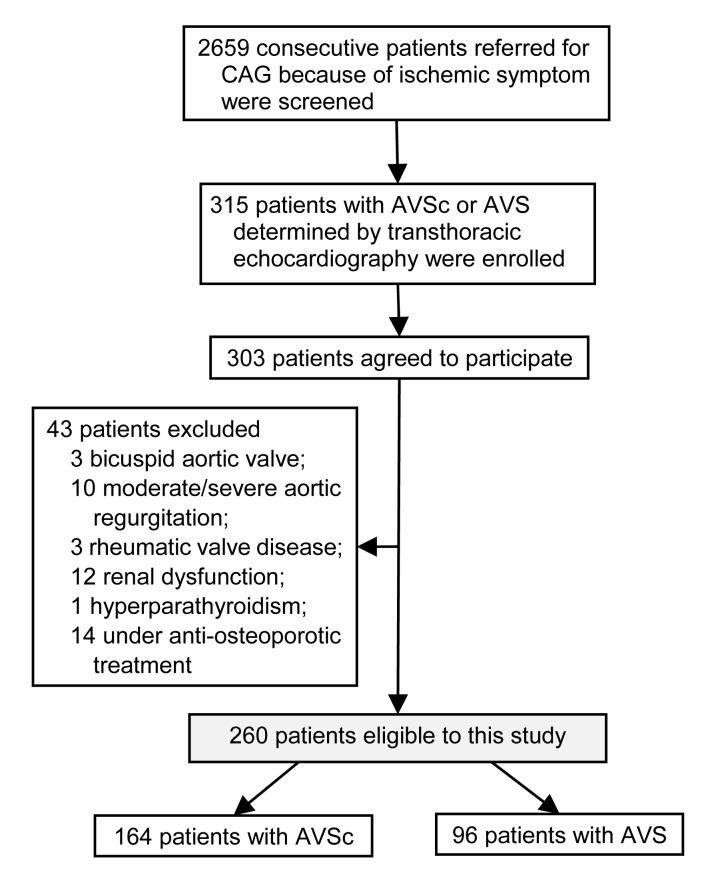

A total of 2659 consecutive patients referred for coronary angiography and echocardiography because of ischemic symptom in the Department of Cardiology at Shanghai Ruijin Hospital (China) between June 2012 and June 2013 were screened. Overall, 303 patients were diagnosed as having CAVD by transthoracic two-dimensional echocardiography and Doppler flow imaging. For the purpose of this study, we excluded patients with bicuspid aortic valve (n=3), moderate/severe aortic regurgitation (n=10), rheumatic valve disease (n=3), moderate/severe renal insufficiency defined as estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (n=12), or known primary hyperparathyroidism (n=1), and those who were receiving anti-osteoporotic treatments (n=14). Among the remaining 260 eligible patients, AVSc was detected in 164 patients and AVS was observed in 96 patients with a peak trans-aortic valve flow velocity ≥2.0 m/s (mean (3.8±1.0) m/s) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patient enrollment

CAG: coronary angiography; AVSc: aortic valve sclerosis; AVS: aortic valve stenosis

We also selected 164 gender- and age-matched patients without CAVD in a 1:1 ratio as a control group.

The study was approved by Shanghai Jiao Tong University Ethics Committee and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave written informed consent.

2.2. Doppler echocardiography

For each patient, M-mode and two-dimensional echocardiography and pulsed and continuous-wave Doppler imaging were performed by two experienced observers blinded to biochemical measurements. AVSc was defined as aortic cusp thickening with normal excursion and a peak trans-aortic valve flow velocity <2.0 m/s. AVS was defined as increased echogenicity, thickening, or calcification of the leaflets with a peak trans-aortic valve flow velocity ≥2.0 m/s.

2.3. Laboratory assessment

Peripheral venous blood was collected in the morning of angiography after an overnight fasting. Serum levels of calcium, phosphate, alkaline phosphatase (AKP), total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL)- and low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, creatinine, aminotransferases, and creatinine kinase were determined using standard methods. Serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25-OHD), osteocalcin, PINP, and β-CTx were measured using automatic electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Cobas E601 analyzer, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH) was measured using an automatic chemiluminescence immunoassay analyzer (Abbott Architect i2000SR analyzer, Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, USA). All assays were done in duplicate by investigators blinded to the clinical and echo-Doppler findings.

2.4. Definitions

Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, or use of antihypertensive medications. Type 2 diabetes mellitus was diagnosed according to the American Diabetes Association criteria, including glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥6.5%, fasting plasma glucose concentration ≥7.0 mmol/L, 2-h postprandial glucose concentration ≥11.1 mmol/L, or a random plasma glucose ≥11.1 mmol/L in a patient with classic symptoms of hyperglycemia or hyperglycemic crisis (ADA, 2010). Hypercholesterolemia was defined by total cholesterol >5.2 mmol/L or under medical treatment. Kidney function was determined by eGFR using the modified Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula. The severity of coronary artery disease was expressed by the number of significantly diseased coronary arteries (luminal diameter stenosis ≥50% in a major epicardial coronary artery and its main branch) and SYNTAX score (http://www.syntaxscore.com) assessed by two independent experienced operators. Hyperparathyroidism was defined as serum iPTH >65 pg/ml.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD) and were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Categorical variables are presented as number and percentages, and were compared with a chi-square test. To determine the relationship between mineral metabolism disturbances and the presence and severity of CAVD, we compared mineral metabolism parameters, including serum calcium, phosphate, AKP, 25-OHD, and iPTH, between patients with and without AVSc and between patients with AVSc and those with AVS. In 96 patients with AVS, the relationship between mineral metabolism parameters and hemodynamic severity of CAVD was established by the Spearman correlation test. The association of mineral metabolism parameters with the presence and severity of CAVD was determined by a multivariate logistic regression model after adjusting for risk factors of coronary artery disease, body mass index, renal function, and coronary angiographic findings. A P-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software for Windows Versions 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics

Patients with AVSc did not significantly differ from controls with respect to cardiovascular risk and severity of coronary artery disease except for elevated serum levels of total and LDL-cholesterol (Table 1). There were no significant differences between patients with AVSc and those with AVS in cardiovascular risk and severity of coronary artery disease (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with CAVD and controls

| Variable | Controls (n=164) | Patients with AVSc (n=164) | Patients with AVS (n=96) | P 1 | P 2 |

| Age (year) | 73.2±7.5 | 73.2±7.5 | 74.1±8.0 | 1.000 | 0.402 |

| Men | 107 (65.2%) | 107 (65.2%) | 59 (61.5%) | 1.000 | 0.540 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 56 (34.1%) | 50 (30.5%) | 29 (30.2%) | 0.479 | 0.962 |

| Hypertension | 128 (78.0%) | 126 (76.8%) | 72 (75.0%) | 0.792 | 0.738 |

| Smoking (current or past) | 42 (25.6%) | 40 (24.4%) | 21 (21.9%) | 0.799 | 0.644 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 51 (31.1%) | 53 (32.3%) | 25 (26.0%) | 0.812 | 0.287 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.77±1.06 | 4.07±0.94 | 4.17±1.07 | 0.007 | 0.396 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.18±0.33 | 1.18±0.30 | 1.19±0.27 | 0.933 | 0.761 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 2.27±0.85 | 2.45±0.81 | 2.54±0.86 | 0.040 | 0.402 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.51±0.92 | 1.51±0.90 | 1.45±0.74 | 0.963 | 0.586 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.2±2.6 | 24.4±3.5 | 23.8±3.4 | 0.458 | 0.120 |

| Glomerular filtration rate (ml/min per1.73 m2) | 78.1±13.8 | 78.2±14.3 | 75.3±15.8 | 0.940 | 0.131 |

| Coronary artery disease | 91 (55.5%) | 96 (58.5%) | 50 (52.1%) | 0.577 | 0.312 |

| 1-vessel | 52 (57.1%) | 55 (57.3%) | 28 (56.0%) | 0.724 | 0.466 |

| 2-vessel | 30 (33.0%) | 34 (35.4%) | 17 (34.0%) | 0.577 | 0.554 |

| 3-vessel | 9 (9.9%) | 7 (7.3%) | 5 (10.0%) | 0.608 | 0.727 |

| SYNTAX score | 12.26±7.38 | 12.91±7.00 | 12.59±7.22 | 0.591 | 0.797 |

Data are expressed as mean±SD or as number (percentage). CAVD: calcific aortic valve disease; AVSc: aortic valve sclerosis; AVS: aortic valve stenosis. P 1: control group vs. patients with AVSc; P 2: patients with AVSc vs. those with AVS

3.2. Biochemical investigation

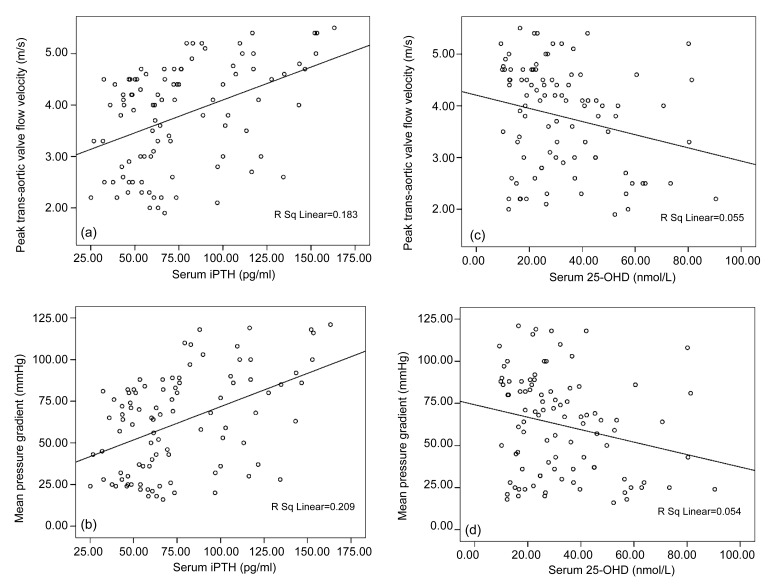

Stepwise increases were observed in serum levels of calcium, phosphate, AKP, iPTH, and biomarkers of bone turnover (osteocalcin, PINP, β-CTx) from control group to patients with AVS, with reverse changes for 25-OHD levels (for all comparisons, P<0.001) (Table 2). In patients with AVS, serum levels of iPTH were positively, in contrast 25-OHD levels were negatively, related to peak trans-aortic flow velocity (r=0.428, P<0.001; r=−0.235, P=0.021, respectively) and mean pressure gradient (r=0.457, P<0.001; r=−0.233, P=0.022, respectively) (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Mineral metabolism parameters and biomarkers of bone turnover of patients with CAVD and controls

| Variable | Controls (n=164) | Patients with AVSc (n=164) | Patients with AVS (n=96) | P 1 | P 2 |

| Mineral metabolism parameters | |||||

| Serum calcium (mg/dl) | 8.39±0.44 | 8.79±0.33 | 9.11±0.57 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Serum phosphate (mg/dl) | 3.06±0.54 | 3.75±0.57 | 4.38±1.05 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| iPTH (pg/ml) | 37.88±13.11 | 55.97±17.96 | 76.12±33.72 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 25-OHD (nmol/L) | 58.48±20.80 | 39.27±16.31 | 32.32±18.58 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| AKP (U/L) | 52.58±15.69 | 70.48±24.63 | 82.40±26.51 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Biomarkers of bone turnover | |||||

| Serum osteocalcin (ng/ml) | 11.80±4.33 | 18.45±8.19 | 21.76±9.53 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Serum PINP (ng/ml) | 30.94±13.67 | 45.24±17.01 | 59.33±32.98 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Serum β-CTx (ng/ml) | 0.32±0.16 | 0.50±0.19 | 0.67±0.35 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Data are expressed as mean±SD. iPTH: intact parathyroid hormone; 25-OHD: 25-hydroxyvitamin D; AKP: alkaline phosphatase; PINP: procollagen I N-terminal peptide; β-CTx: β-isomerized type I collagen C-telopeptide breakdown products; CAVD: calcific aortic valve disease; AVSc: aortic valve sclerosis; AVS: aortic valve stenosis. P 1: control group vs. patients with AVSc; P 2: patients with AVSc vs. those with AVS

Fig. 2.

Correlation between mineral metabolism parameters and hemodynamic severity of CAVD

Serum levels of iPTH correlated positively (a, b), but 25-OHD inversely (c, d), with peak trans-aortic valve flow velocity and mean pressure gradient. iPTH: intact parathyroid hormone; 25-OHD: 25-hydroxyvitamin D

3.3. Multivariate analysis

After adjusting for risk factors of coronary artery disease, body mass index, renal function, and number of disease coronary arteries, increased serum levels of calcium, phosphate, AKP, and iPTH and reduced serum levels of 25-OHD were independently associated with the presence and severity of CAVD (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association between mineral metabolism measurements and the presence and severity of CAVD

| Variable | Univariate |

Multivariate |

||

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Presence of CAVD | ||||

| Total cholesterol | 1.355 (1.083–1.695) | 0.008 | 0.873 (0.318–2.396) | 0.793 |

| LDL-cholesterol | 1.320 (1.011–1.724) | 0.041 | 1.014 (0.297–3.459) | 0.982 |

| Serum calcium | 14.845 (7.298–30.197) | <0.001 | 10.018 (3.364–29.835) | <0.001 |

| Serum phosphate | 9.840 (5.721–16.922) | <0.001 | 3.945 (1.955–7.959) | <0.001 |

| AKP | 1.058 (1.041–1.076) | <0.001 | 1.037 (1.013–1.062) | 0.003 |

| 25-OHD | 0.943 (0.930–0.957) | <0.001 | 0.950 (0.932–0.969) | <0.001 |

| iPTH | 1.077 (1.058–1.097) | <0.001 | 1.068 (1.041–1.097) | <0.001 |

| Severity of CAVD | ||||

| Serum calcium | 5.662 (2.829–11.331) | <0.001 | 6.984 (2.736–17.825) | <0.001 |

| Serum phosphate | 3.275 (2.097–5.116) | <0.001 | 3.665 (1.985–6.765) | <0.001 |

| AKP | 1.018 (1.008–1.029) | 0.001 | 1.016 (1.003–1.029) | 0.019 |

| 25-OHD | 0.975 (0.959–0.991) | 0.002 | 0.971 (0.951–0.992) | 0.006 |

| iPTH | 1.032 (1.020–1.044) | <0.001 | 1.037 (1.021–1.053) | <0.001 |

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; CAVD: calcific aortic valve disease; LDL: low density lipoprotein; AKP: alkaline phosphatase; 25-OHD: 25-hydroxyvitamin D; iPTH: intact parathyroid hormone

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrates an association of abnormal metabolism of calcium and phosphate with the presence and severity of CAVD in patients with normal or mildly impaired renal function, suggesting that medical treatment targeting mineral metabolism disturbance may be a novel strategy to retard the development and progression of CAVD.

4.1. Relation between mineral metabolism disturbance and CAVD

Calcification has been shown to be an integral part of disease onset and progression in the histopathologic studies of AVS (Parolari et al., 2009; Yetkin and Waltenberger, 2009). Previous studies have shown that dysregulation of calcium and phosphate metabolism with high parathyroid hormone and low 25-hydroxyvitamin levels correlated with the severity of AVS in patients with preserved renal function with or without coronary artery disease (Mills et al., 2004; Linhartová et al., 2008; Akat et al., 2010). However, the majority of these patients had severe AVS. Recently, Akat et al. (2009) reported that foci of micro-calcification have been observed in the early stage of CAVD (AVSc or mild AVS). In the Cardiovascular Health Study, elevated phosphate levels, but not calcium, parathyroid hormone, or 25-OHD levels in serum, were associated with AVSc in a community-based cohort of older adults (Linefsky et al., 2011). The lack of association between major mineral metabolism measurements except serum phosphate and AVSc may be, at least partly, related to the exclusion of those with known cardiovascular disease. In comparison with previous reports (Mills et al., 2004; Linhartová et al., 2008; Akat et al., 2010), our study population was specially selected, as all patients had AVSc or AVS by trans-thoracic two-dimensional echocardiography and Doppler flow imaging and were in normal or mildly impaired renal function. Our results suggest that mineral metabolism disturbances were independently associated with both presence and severity of CAVD in these patients, irrespective of presence or absence of cardiovascular disease.

The potential mechanism responsible for the association between abnormal calcium and phosphate metabolism and valve calcification is likely to be complex. Soft tissue calcification has been thought to be an entirely passive physicochemical process that is driven by serum levels of calcium and phosphate (O'Neill, 2007). Recent evidence increasingly suggests that this process involves cellular events, extracellular matrix composition, and other regulators of mineral metabolism, supporting a notion that CAVD is also an active course (Rajamannan, 2009; Yetkin and Waltenberger, 2009). Parathyroid hormone and 25-OHD are the most important regulators of calcium and phosphate metabolism, particularly for both bone formation and osteoblast activity. In this study, there were significant differences in bone turnover markers between patients with AVSc or AVS and those without, suggesting that CAVD may be a state with decreased bone turnover, similar to the features of osteoporosis in elderly people. In the COFRASA study, Hekimian et al. (2013) reported that progression of AVS was associated with calcium-phosphorus metabolism and a bone resorptive remodeling. Recently, Nagy et al. (2013) found a close relation between circulating mediators of bone homeostasis and severity of AVS.

4.2. Clinical implications

Since the burden of CAVD is expected to increase rapidly with aging of the population, strategies to slow down or reverse the progression of CAVD become important (Iung et al., 2003). Our study showed that abnormal lipid metabolism reflected by elevated serum levels of total and LDL-cholesterol was not an independent factor for the presence of CAVD. In contrast, degeneration of heart valve tissue may be caused by mineral metabolism disturbances. The effect of osteoporosis therapy has been investigated because of an association between aortic valve calcification and low skeletal bone mineral density (Aksoy et al., 2005). Several small observational studies demonstrated a possible link between use of bisphosphonates and slowing of AVS progression (Skolnick et al., 2009; Sterbakova et al., 2010; Innasimuthu and Katz, 2011), although such beneficial effects may be not remarkable in older women (Aksoy et al., 2012). Taken together, prospective randomized clinical studies are certainly needed to evaluate the role of regulation of calcium and phosphate metabolism for preventing progression of CAVD especially at its early stage.

4.3. Study limitations

We recognized limitations in our study. The study presented here is cross-sectional, thereby allowing us to detect association, but not to infer causality or formulate predictions. Furthermore, several exclusion criteria may introduce selection biases, and the relationship between mineral metabolism disturbance and progression of CAVD was not assessed. Finally, valvular fibrosis, as well as calcification, restricts cusp movement, and CAVD may be more appropriately viewed as a fibrocalcific disease.

5. Conclusions

This study suggests an association between mineral metabolism disturbance and the presence and severity of CAVD in patients with normal or mildly impaired renal function. Large-scale prospective studies are needed to assess the effects of medical treatment targeting mineral metabolism disturbance on the development and progression of CAVD.

Footnotes

Project supported by the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (No. 114119a8800), China

Compliance with ethics guidelines: Zhen-kun YANG, Chen YING, Hong-yan ZHAO, Yue-hua FANG, Ying CHEN, and Wei-feng SHEN declare that they have no conflict of interest.

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study. Additional informed consent was obtained from all patients for whom identifying information is included in this article.

References

- 1.ADA (American Diabetes Association) Standards of medical care in diabetes 2010. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(Suppl. 1):S11–S61. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akat K, Borggrefe M, Kaden JJ. Aortic valve calcification: basic science to clinical practice. Heart. 2009;95(8):616–623. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.134783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akat K, Kaden JJ, Schmitz F, et al. Calcium metabolism in adults with severe aortic valve stenosis and preserved renal function. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105(6):862–864. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aksoy O, Cam A, Goel SS, et al. Do bisphosphonates slow the progression of aortic stenosis? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(16):1452–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aksoy Y, Yagmur C, Tekin GO, et al. Aortic valve calcification: association with bone mineral density and cardiovascular risk factors. Coron Artery Dis. 2005;16(6):379–383. doi: 10.1097/00019501-200509000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman RV, Otto CM. Spectrum of calcific aortic valve disease: pathogenesis, disease progression, and treatment strategies. Circulation. 2005;111(24):3316–3326. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.486738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hekimian G, Boutten A, Flamant M, et al. Progression of aortic valve stenosis is associated with bone remodeling and secondary hyperparathyroidism in elderly patients—the COFRASA study. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(25):1915–1922. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Innasimuthu AL, Katz WE. Effect of bisphosphonates on the progression of degenerative aortic stenosis. Echocardiography. 2011;28(1):1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2010.01256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iung B, Baron G, Butchart EG, et al. A prospective survey of patients with valvular heart disease in Europe: the Euro Heart Survey on valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2003;24(13):1231–1243. doi: 10.1016/S0195-668X(03)00201-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwata S, Hyodo E, Yanagi S, et al. Parathyroid hormone and systolic blood pressure accelerate the progression of aortic valve stenosis in chronic hemodialysis patients. Int J Cardiol. 2013;163(3):256–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kume T, Kawamoto T, Akasaka T, et al. Rate of progression of valvular aortic stenosis in patients undergoing dialysis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2006;19(7):914–918. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2006.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linefsky JP, O'Brien KD, Katz R, et al. Association of serum phosphate levels with aortic valve sclerosis and annular calcification: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(3):291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linhartová K, Veselka J, Sterbáková G, et al. Parathyroid hormone and vitamin D levels are independently associated with calcific aortic stenosis. Circ J. 2008;72(2):245–250. doi: 10.1253/circj.72.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mills WR, Einstadter D, Finkelhor RS. Relation of calcium-phosphorus production to the severity of aortic stenosis in patients with normal renal function. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94(9):1196–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.07.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagy E, Eriksson P, Yousry M, et al. Valvular osteoclasts in calcification and aortic valve stenosis severity. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(3):2264–2271. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.01.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Neill WC. The fallacy of the calcium-phosphorus product. Kidney Int. 2007;72(7):792–796. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parolari A, Loardi C, Mussoni L, et al. Nonrheumatic calcific aortic stenosis: an overview from basic science to pharmacological prevention. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;35(3):493–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parolari A, Tremoli E, Cavallotti L, et al. Do statins improve outcomes and delay the progression of non-rheumatic calcific aortic stenosis? Heart. 2011;97(7):523–529. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.215046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajamannan NM. Calcific aortic stenosis: lessons learned from experimental and clinical studies. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29(2):162–168. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.156752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajamannan NM, Evans FJ, Aikawa E, et al. Calcific aortic valve disease: not simply a degenerative process: a review and agenda for research from the national heart and lung and blood institute aortic stenosis working group. Circulation. 2011;124(16):1783–1791. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.006767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skolnick AH, Osranek M, Formica P, et al. Osteoporosis treatment and progression of aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104(1):122–124. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stefenelli T, Mayr H, Bergler-Klein J, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism: incidence of cardiac abnormalities and partial reversibility after successful parathyroidectomy. Am J Med. 1993;95(2):197–202. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90260-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sterbakova G, Vyskocil V, Linhartova K. Bisphosphonates in calcific aortic stenosis: association with slower progression in mild disease—a pilot retrospective study. Cardiology. 2010;117(3):184–189. doi: 10.1159/000321418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strickberger SA, Schulman SP, Hutchins GM. Association of Paget’s disease of bone with calcific aortic valve disease. Am J Med. 1987;82(5):953–956. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90157-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teo KK, Corsi DJ, Tam JW, et al. Lipid lowering on progression of mild to moderate aortic stenosis: meta-analysis of the randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials on 2344 patients. Can J Cardiol. 2011;27(6):800–808. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yetkin E, Waltenberger J. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of aortic stenosis. Int J Cardiol. 2009;135(1):4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.03.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]