Abstract

Objective

Valve sparing root replacement (VSRR) is an attractive option for the management of aortic root aneurysms with a normal native aortic valve. Therefore, we reviewed our experience with a modification of the David V VSRR and compared it with stented pericardial bioprosthetic valve conduit (BVC) root replacement in an age-matched cohort of older patients.

Methods

A total of 48 VSRRs were performed at our institution, excluding those on bicuspid aortic valves. We compared these cases with 15 aortic root replacements performed using a BVC during the same period. Subgroup analysis was performed comparing 16 VSRR cases and 15 age-matched BVC cases.

Results

The greatest disparity between the VSRR and BVC groups was age (53 vs 69 years, respectively; P < .0005). The matched patients were similar in terms of baseline demographics and differed only in concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting (2 VSRR vs 7 BVC patients; P = .036). None of the VSRR and 3 of the BVC procedures were performed for associated dissection (P = .101). Postoperative aortic insufficiency grade was significantly different between the 2 groups (P = .004). The cardiopulmonary bypass, crossclamp, and circulatory arrest times were not different between the VSRR and BVC groups (174 vs 187 minutes, P = .205; 128 vs 133 minutes, P = .376; and 10 vs 13 minutes, respectively; P = .175). No differences were found between the 2 groups with respect to postoperative complications. One postoperative death occurred in the BVC group and none in the VSRR group. The postoperative length of stay and aortic valve gradients were less in the VSRR group (6 vs 8 days, P = .038; 6 vs 11.4 mm Hg, P = .001). The intensive care unit length of stay was significantly less in the VSRR group (54 vs 110 hours, P = .001).

Conclusions

VSRR is an effective alternative to the BVC for aortic root aneurysm.

Since the original description of the use of a mechanical valve conduit for replacement of the aortic valve and ascending aorta by Wheat and colleagues1 and then Bentall and De Bono,2 an evolution of aortic root surgery has resulted in a movement to preserve the valve during root replacement. Patients requiring aortic root replacement for aneurysmal disease have historically been treated by complete excision of the aneurysm and valve, followed by replacement with a composite valve conduit (biologic or mechanical) or homograft aortic root. David and Feindel3 and Sarsam and Yacoub4 described techniques for valve sparing root replacement (VSRR), with multiple subsequent iterations for use in patients with aortic root aneurysms requiring aortic root replacement. Preservation of the native valve could avoid the potential complications related to the use of mechanical or bioprosthetic tissue valves, including freedom from anticoagulation and the theoretical risk of structural valve deterioration.

Accordingly, VSRR is an attractive treatment of aortic root aneurysm with a normal aortic valve for the initiated surgeon. Although technically more demanding, excellent early and late outcomes after VSRR have been reported.5 Very few published reports comparing modern VSRR and bioprosthetic valve conduits (BVCs) are available. Therefore, we reviewed our experience with a modification of the David V VSRR and compared it with stented pericardial BVC root replacement in an age-matched cohort of older patients.

METHODS

From March 2003 to December 2012, 70 patients underwent VSRR by 1 surgeon (J.S.I.). Of these 70 patients, those with bicuspid aortic valves (n = 22) were excluded. For the remaining 48 patients (12 women and 36 men), the age range was 21 to 77 years. We compared these 48 VSRR procedures with 15 BVC procedures performed with the Carpentier Edwards Pericardial valve (Edwards Lifesciences Corp, Irvine, Calif) during the same period and by the same surgeon (J.S.I.). In the VSRR group, the etiology of the aortic root aneurysm was degenerative in most patients (n = 43) and aortic dissection in 5. Of the 15 BVC patients, the indication for surgery was degenerative disease in 12 and dissection in 3. All patients had aortic root aneurysmal disease that met standard size criteria (ie, >5.0 cm diameter or >2 times the size of a normal aortic segment) for resection. However, the greatest disparity between the 2 groups was patient age. Therefore, the 15 BVC patients were matched by age with 16 of the older VSRR patients. Data were collected prospectively as a part of our institutional participation in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons database and retrospectively from a review of the medical records for additional information not obtained prospectively. The preoperative patient characteristics are listed in Table 1, and the intraoperative variables are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Patient demographic data and risk factors

| Variable | VSRR (n = 16) |

BVC (n = 15) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 65 ± 20 | 69 ± 7 | .079 |

| Height (cm) | 176 ± 9 | 175 ± 13 | .803 |

| Weight (kg) | 84 ± 11 | 88 ± 19 | .532 |

| BSA (m2) | 2.00 ±0.17 | 2.03 ± 0.27 | .760 |

| Etiology | .101 | ||

| Dissection | 0 (0) | 3 (20) | |

| Aneurysm | 16 (100) | 12 (80) | |

| Angiographically proven CAD | .162 | ||

| Normal arteries | 9 (56) | 3 (20) | |

| Nonobstructive CAD | 3 (19) | 4 (27) | |

| Obstructive CAD | 3 (19) | 7 (47) | |

| Unknown | 1 (6) | 1 (7) | |

| Reoperation | 2 (13) | 3 (20) | .654 |

| Elective status | 15 (94) | 13 (87) | .600 |

| Current smoker | 3 (19) | 2 (13) | 1.000 |

| Diabetes | 2 (13) | 3 (20) | .654 |

| Dyslipidemia | 10 (63) | 10 (67) | 1.000 |

| Hypertension | 14 (88) | 14 (93) | 1.000 |

| Endocarditis | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | .484 |

| COPD | 2 (13) | 1 (7) | 1.000 |

| Immunocompromise | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| PVD | 1 (6) | 2 (13) | .600 |

| Previous MI | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| CVA | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Angina | 2 (13) | 3 (20) | .654 |

| Arrhythmia | 4 (25) | 1 (7) | .333 |

Data presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%). VSRR, Valve sparing root replacement; BVC, bioprosthetic valve conduit; BSA, body surface area; CAD, coronary artery disease; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; MI, myocardial infarction; CVA, cerebrovascular disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulomonary disease.

TABLE 2.

Operative characteristics

| Variable | VSRR (n = 16) |

BVC (n = 15) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concomitant CABG | .036 | ||

| None | 14 (88) | 8 (53) | |

| Single vessel | 2 (13) | 5 (33) | |

| Double vessel | 0 (0) | 2 (13) | |

| CPB (min) | .205 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 174 ± 26 | 187 ± 32 | |

| Median | 169 | 180 | |

| Range | 144–262 | 143–260 | |

| Crossclamp time (min) | .376 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 128 ± 12 | 133 ± 22 | |

| Median | 125 | 134 | |

| Range | 109–152 | 92–177 | |

| Circulatory arrest time (min) | .175 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 10 ± 2 | 13 ± 7 | |

| Median | 10 | 11 | |

| Range | 7–15 | 6–35 | |

| Valve/Hegar size (mm) | .048 | ||

| Median | 22 | 25 | |

| Range | 20–25 | 21–27 | |

| Valve/Hegar size indexed to BSA | 11.1 ± 0.6 | 11.9 ± 1.4 | .060 |

| Aortic root graft size | <.0005 | ||

| Median | 34 | 28 | |

| Range | 26–36 | 26–34 |

Data presented as n (%) or mean ± SD, unless otherwise noted. VSRR, Valve sparing root replacement; BVC, bioprosthetic valve conduit; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; SD, standard deviation; BSA, body surface area.

The institutional review board of the Medical University of South Carolina approved the present study and waived the need for individual patient consent.

Operative Technique

VSRR was performed as described previously.7 In brief, cannulation for cardiopulmonary bypass was obtained by way of the ascending aorta and right atrial appendage. Cardiac arrest was achieved with a combination of antegrade and retrograde cold blood cardioplegia. After transection of the ascending aortic aneurysm, the aortic valve was inspected for pathologic features that might preclude its preservation. When the valve was deemed acceptable for preservation (nonsclerotic without obvious large fenestrations or other imperfections), the aneurysm was excised, leaving a 5- to 8-mm rim of aortic tissue around the native valve and around the coronary ostia. Next, horizontal mattress sutures were placed circum-ferentially under the aortic valve annulus from inside to out and across an appropriately sized Dacron graft (Hemashield; Meadox Medicals, Oakland, NY; and Dacron; DuPont, Wilmington, Del). Graft sizing was achieved by adding 11 mm to the Hegar dilator-sized annulus (2.5-mm allowance for aortic wall thickness on either side of the outflow graft [5 mm total] and 6 mm for billowing of the neosinus graft). The Dacron graft was seated such that the valve was contained within the graft. The sutures were tied with an appropriately sized Hegar dilator gently placed across the aortic valve (to prevent overplication of the graft and constriction of the annulus and left ventricular outflow tract) and cut. The valve was then attached to the wall of the Dacron graft using running polypropylene suture followed by reimplantation of the coronary arteries in anatomic fashion. After re-establishment of arterial continuity, the patients were warmed and weaned from cardiopulmonary bypass.

The stented pericardial BVC was performed by first excising the native aortic leaflets and fashioning coronary buttons in the usual manner. Everting pledgeted mattress sutures were placed circumferentially around the annulus. The valve conduit was then constructed using running horizontal mattress sutures to affix an appropriately sized pericardial valve within a Dacron graft approximately 10 cm long. Root replacement proceeded as usual.

Statistical Analysis

The variables compared included demographic data, preoperative risk factors, intraoperative measures, and postoperative outcomes. The normality of the continuous variables was evaluated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistic, and between-group comparisons were performed using the Student t or Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate. Fisher’s exact test was used to examine categorical variables. All tests were performed using SPSS 22 (SPSS Inc, Chicago Ill).

RESULTS

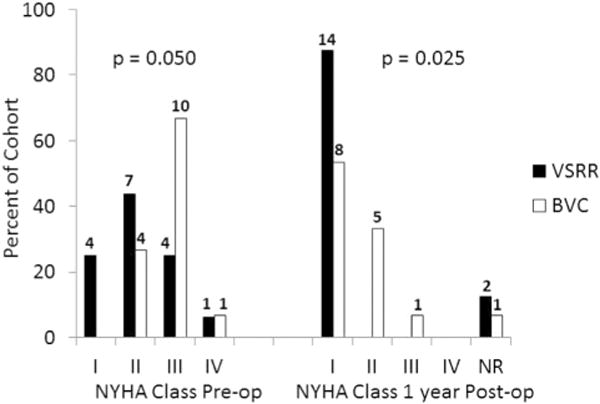

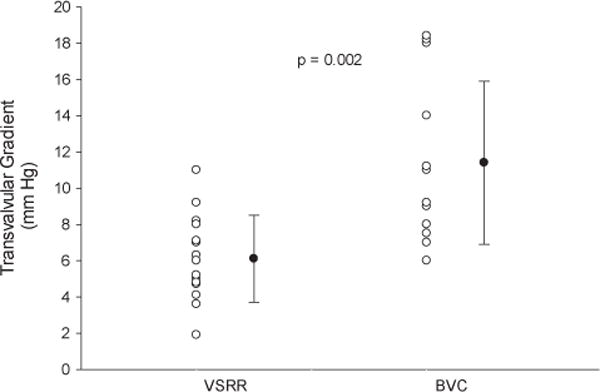

Patient demographics, operative characteristics, and early postoperative outcomes are summarized in Tables 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The greatest disparity between the VSRR and BVC groups was age (55 vs 69 years, respectively; P <.0005). Therefore, the 16 oldest VSRR patients were matched by age with the 15 BVC patients. These patients were similar in height, weight, sex, and race and differed only in the use of concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting (2 VSRR and 7 BVC; P = .036). Within the 31-matched patients, the indication for surgery was dissection in no VSRR patient and 3 BVC patients (P = .224). In the VSRR group, 11 patients were in New York Heart Association (NYHA) class I or II and 5 were in NYHA class III or IV preoperatively. In the BVC group, 4 patients were in NYHA class I or IIand 11were in NYHA class III or IVpre-operatively. At 1 year postoperatively (approximate, given scheduling of follow-up visits), 100% of the VSRR group (n = 14, 2 were lost to follow-up) were NYHA class I, and in the BVC group, 13 were NYHA class I or II and 1 was in NYHA class III (Figure 1). The cardiopulmonary bypass, crossclamp, and circulatory arrest times were not different between the VSRR and BVC groups (174 vs 187 minutes, P = .205; 128 vs 133 minutes, P = .376; and 10 vs 13 minutes, respectively; P = .175). No differences were found with respect to postoperative complications. One death occurred in the BVC group and none in the VSRR group. Two permanent strokes occurred in the BVC group and none in the VSRR group. The intensive care unit length of stay was significantly shorter in the VSRR group (54 vs 110 hours; P = .001), as was the overall postoperative length of stay (6 vs8 days; P = .038). The cause of immunocompromise in the VSRR patient was treatment of ulcerative colitis. The reasons for previous surgery in the VSRR group were endocarditis in 1 patient and ascending aorta replacement for aneurysm in 1 patient. The reasons for previous surgery in the BVC group was pulmonary autograft dilation after Ross in 1 patient, previous root replacement with a St Jude conduit in 1 patient, and previous repair of traumatic descending aortic tear in 1 patient (Table 1). The reasons for prolonged length of stay included pulmonary embolus in 1, pneumonia in 3, stroke in 1, atrial fibrillation in 1, and reoperation for bleeding in 1. The transvalvular gradients were lower in the VSRR group (6 vs 11.4 mm Hg; P = .001; Figure 2). Postoperative aortic insufficiency was graded as none in 7, trace in 3, mild in 5, and not recorded in 1 VSRR patient. It was graded as none in 14 and not recorded in 1 BVC patient.

TABLE 3.

Early postoperative outcomes

| Variable | VSRR (n = 16) |

BVC (n = 15) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reoperation for bleeding | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 1.000 |

| Sepsis | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 1.000 |

| Permanent stroke | 0 (0) | 2 (13) | .483 |

| Ventilator prolonged | 1 (7) | 2 (13) | 1.000 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Pneumonia | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 1.000 |

| Renal failure | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 1.000 |

| Operative death | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 1.000 |

| Mortality or major morbidity | 2 (13) | 5 (33) | .390 |

| Reoperation for pacemaker implantation | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 1.000 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 4 (25) | 6 (40) | .458 |

| ICU LOS (h) | .001 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 54 ± 45 | 110 ± 38 | |

| Median | 45 | 120 | |

| Range | 18–173 | 51–166 | |

| Total LOS (d) | .019 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 7 ± 2 | 10 ± 6 | |

| Median | 6 | 9 | |

| Range | 4–12 | 5–27 | |

| Postoperative LOS (d) | .038 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 6 ± 2 | 8 ± 3 | |

| Median | 6 | 8 | |

| Range | 4–11 | 4–16 | |

| Postoperative gradient (mm Hg) | .001 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 6.0 ± 2.4 | 11.4 ± 4.5 | |

| Median | 5.6 | 10.0 | |

| Range | 1.9–11.0 | 6.0–18.0 | |

| Postoperative AI (immediately postoperatively) | .004 | ||

| None | 7 (44) | 14 (93) | |

| Trace | 3 (19) | 0 (0) | |

| Mild | 5 (31) | 0 (0) | |

| Not recorded | 1 (6) | 1 (7) |

Data presented as n (%), unless otherwise noted. VSRR, Valve sparing root replacement; BVC, bioprosthetic valve conduit; SD, standard deviation; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; AI, aortic insufficiency.

FIGURE 1.

New York Heart Association (NYHA) class preoperatively (Pre-op) and 1-year postoperatively (Post-op) in the valve sparing root replacement (VSRR) and bioprosthetic valve conduit (BVC) groups. The number of patients is indicated at the top of each bar. Two VSRR patients were lost to follow-up before 1 year postoperatively, and 1 BVC patient died intraoperatively.

FIGURE 2.

Aortic valve gradients in valve sparing root replacement (VSRR) and bioprosthetic valved conduit (BVC) groups.

DISCUSSION

In older patients, the perceived risks of VSRR might appear to outweigh the benefits of this technically challenging procedure. The results of the present study have demonstrated that VSRR is an effective alternative to BVC in older patients with aortic root aneurysm. BVC has previously been considered the standard of care for aortic root aneurysm. However, approximately 30% of the patients who undergo aortic root replacement will have a morphologically normal aortic valve.7 The possibility of sparing the native aortic valve affords the patient the freedom from the inherent drawbacks of a valved conduit (ie, the need for anticoagulation in the case of a mechanical prosthesis and the theoretical risk of structural deterioration in the case of a biologic valve).

Limited data are available comparing the VSRR procedure and that of a valved conduit for aortic root aneurysm. In 2001, Kallenbach and colleagues6 reported a comparison of VSRR and mechanical valve conduit replacement. Of note, the operative times were shorter and bleeding complications more frequent in the valve conduit replacement group. In contrast, a single patient in the VSRR group required reoperation for valve failure.6 Since then, no reports have been published comparing modern VSRR and valve conduit replacement. Compared with the results from Kallenbach and colleagues,6 our circulatory arrest times were considerably shorter (19 and 25 minutes in their study vs 10 and 13 minutes in our study for the VSRR and BVC groups, respectively). Furthermore, in our cohort, the overall hospital length of stay was significantly shorter (18 and 21 days vs 6 and 8 in our VSRR and BVC groups, respectively) despite our patients being nearly 1 decade older. These improvements might have resulted from improvements in the surgical technique and postoperative care over time because their report predated ours by 12 years. None of our patients required reoperation for bleeding compared with 9 total reoperations in the study by Kallenbach and colleagues6 for bleeding, pacemaker implantation, and subxiphoid drainage. The transvalvular gradients were not reported in their study6; however, we found lower gradients in the VSRR group (6 vs 11.4 mm Hg for VSRR and BVC, respectively; Figure 2). Aortic insufficiency was mild or less in all VSRR patients on the postoperative echocardiogram, with more than one half of those patients having no insufficiency detectable. Not surprisingly, aortic insufficiency was not identified in any of the BVC patients postoperatively.

A number of others have published their experience in using either BVC or valve-sparing techniques in treating similar patients. Moorjani and colleagues8 compared their experience with a commercially available prefabricated valved conduit versus a hand-sewn BVC, such as was used in the present study. They found less bleeding, a lower requirement for transfusion, and similar gradients immediately postoperatively with the commercially available aortic root prosthesis.8 Subramanian and colleagues9 retrospectively compared the outcomes of patients with acute type A dissection and found similar long-term results, including the degree of postoperative aortic insufficiency and overall survival between patients who had undergone a Bentall procedure and those who had undergone a Yacoub or David VSRR. Cameron and collagues10 reviewed the Johns Hopkins experience using various methods of aortic root replacement in patients with Marfan disease. During the 30-year course of their retrospective analysis, the frequency of VSRR exceeded that of the modified Bentall during the last 8 years (1998–2006). They concluded that the durability of valve-sparing procedures had not yet proved equivalent over the long term.10 Finally, the work of Etz and colleagues11 adds a notable observation to the published data in that of 275 patients who underwent aortic root replacement with bovine pericardial valved conduits, a single patient had required reoperation for structural degeneration of the valve at 12 years postoperatively.

The present study had several important limitations. It was retrospective and therefore subject to significant bias. The decision to proceed with VSRR or BVC was at the discretion of the attending surgeon and might have been influenced by concomitant procedures or perceived surgical risk. Almost one half of the BVC patients (47%) had undergone concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting, which artificially increased the operative, bypass, and crossclamp times for this group. There were 3 dissections in the BVC group compared with none in the VSRR group. Long-term follow-up data, specifically echocardiographic follow-up data, were not available to determine whether the older VSRR recipients benefited as fully as did younger VSRR patients from this procedure. Finally, the exclusive use of the Carpentier Edwards pericardial valves in the present series might have resulted in higher or lower valvular gradients, depending on whether an alternative valve or conduit (homograft, stentless root) had been selected.

CONCLUSIONS

Our experience has shown that in older patients, a technically more challenging approach to the aortic root, compared with BVC, can be undertaken, with similar operative times and overall morbidity and mortality, shorter hospital stays, and superior postoperative hemodynamic results, avoiding the potential morbidity associated with anticoagulation for mechanical valves. However, our findings cannot yet be generalized to all patients with aortic root aneurysm. Therefore, more research is needed to determine whether this is an appropriate procedure for older patients undergoing high-risk or concomitant procedures.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BVC

bioprosthetic valve conduit

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

- VSRR

valve sparing root replacement

Footnotes

Disclosures: Authors have nothing to disclose with regard to commercial support.

References

- 1.Wheat MW, Jr, Boruchow IB, Ramsey HW. Surgical treatment of aneurysms of the aortic root. Ann Thorac Surg. 1971;12:593–607. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)64795-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bentall H, De Bono A. A technique for complete replacement of the ascending aorta. Thorax. 1968;23:338–9. doi: 10.1136/thx.23.4.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.David TE, Feindel CM. An aortic valve-sparing operation for patients with aortic incompetence and aneurysm of the ascending aorta. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1992;103:617–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarsam MA, Yacoub M. Remodeling of the aortic valve annulus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;105:435–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.David TE. Aortic root aneurysms: remodeling or composite replacement? Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64:1564–8. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(97)01026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kallenbach K, Pethig K, Schwarz M, Milz A, Haverich A, Harringer W. Valve sparing aortic root reconstruction versus composite replacement—perioperative course and early complications. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;20:77–81. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(01)00750-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikonomidis JS. Valve-sparing aortic root replacement—“T. David V” method. Op Tech Thor Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;14:281–96. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moorjani N, Mattam K, Barlow C, Tsang G, Haw M, Livesey S, et al. Aortic root replacement using a biovalsalva prosthesis in comparison to a “handsewn” composite bioprosthesis. J Card Surg. 2010;25:321–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2010.01015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Subramanian S, Leontyev S, Borger MA, Trommer C, Misfeld M, Mohr FW. Valve-sparing root reconstruction does not compromise survival in acute type A aortic dissection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94:1230–4. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.04.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cameron DE, Alejo DE, Patel ND, Nwakanma LU, Weiss ES, Vricella LA, et al. Aortic root replacement in 372 Marfan patients: evolution of operative repair over 30 years. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:1344–9. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.01.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Etz CD, Tobias HM, Rane N, Bodian CA, Di Luozzo G, Plestis KA, et al. Aortic root reconstruction with a bioprosthetic valved conduit: a consecutive series of 275 procedures. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:1455–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]