Abstract

Background and objective Smartphone applications (apps) have the potential to be valuable self-help interventions for depression screening. However, information about their feasibility and effectiveness and the characteristics of app users is limited. The aim of this study is to explore the uptake, utilization, and characteristics of voluntary users of an app for depression screening.

Methods This was a cross-sectional study of a free depression screening smartphone app that contains the demographics, patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9), brief anxiety test, personalized recommendation based on the participant's results, and links to depression-relevant websites. The free app was released globally via Apple's App Store. Participants aged 18 and older downloaded the study app and were recruited passively between September 2012 and January 2013.

Findings 8241 participants from 66 countries had downloaded the app, with a response rate of 73.9%. While one quarter of the participants had a previous diagnosis of depression, the prevalence of participants with a higher risk of depression was 82.5% and 66.8% at PHQ-9 cut-off 11 and cut-off 15, respectively. Many of the participants had one or more physical comorbid conditions and suicidal ideation. The cut-off 11 (OR: 1.4; 95% CI 1.2 to 1.6), previous depression diagnosis (OR: 1.3; 95% CI1.2 to 1.5), and postgraduate educational level (OR: 1.2; 95% CI 1.0 to 1.5) were associated with completing the PHQ-9 questionnaire more than once.

Conclusions Smartphone apps can be used to deliver a screening tool for depression across a large number of countries. Apps have the potential to play a significant role in disease screening, self-management, monitoring, and health education, particularly among younger adults.

Keywords: public health, Depression , smartpone , SCREENING , Mental health, Apps

INTRODUCTION

A smartphone is a mobile phone with advanced hardware and software capabilities that enable it to perform complex functions similar to those of personal computers.1 In 2012, smartphone usage rates accounted for 76% of all mobile phone handsets in Australia,2 72% in the UK,3 88% in Singapore,4 and 65% in the USA.5 The utilization of smartphone apps as a new modality to administer depression screening offers instantaneous feedback and access to screening tools without internet connectivity, provides the ability for users to locally store and access their data, saves time and money, and provides more privacy. In addition, a smartphone's proximity to its user makes health-related apps available anytime/anywhere.

In a recent study, 72% of psychiatric patients in a teaching hospital reported that their phone was a smartphone, and 50% showed interest in using an app on a daily basis to monitor their mental health condition.6 Furthermore, there have been studies exploring the role of mobile phone apps in depression self-management, with results indicating that apps are associated with a decrease in depressive symptoms.7,8

Given the accessibility of smartphones and the potential benefits of depression self-management, the role of smartphone apps in population screening and monitoring should be further explored. However, despite the widespread use of smartphone apps, there have been no studies to date looking at the use of smartphone apps for depression. The aim of this study was to explore the uptake, app usage, and characteristics of voluntary, global users of a smartphone app for depression screening. Specifically, we aimed to answer the following questions: (1) Are smartphone users looking for depression screening apps, and do they use them? (2) What are their characteristics, and how do they use the app? (3) Do smartphone users need depression intervention apps?

METHODS

Design

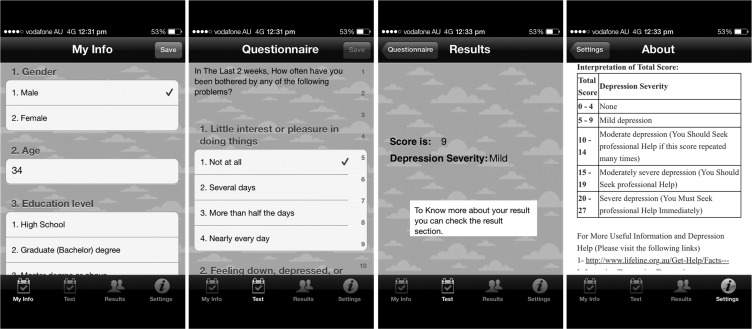

This is a cross-sectional study of a free smartphone depression app (‘Depression Monitor’) that was developed in English utilizing the ‘Health Monitor’ app template9 and released on Apple's App Store globally. After submitting the demographics and baseline data on the first screen of the app—including previous depression diagnosis and treatment and an adapted version of the Charlson comorbidity index (figure 1)—the app users are able to complete the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) on the second screen and can save the history of their results on their devices. PHQ-9 was selected over other depression screening tools because: (1) it has been validated for use among various age groups, including adolescents, adults, and the elderly10–12; and (2) it has been shown to have similar performance regardless of the mode of administration (eg, patient self-report, interviewer-administered in person or by telephone, or touch-screen devices).13 If participants’ depression scores are high, they are advised to take their results to their healthcare professional for further assessment and are provided with an explanation of their results plus links to depression information websites. The app was built with a weekly reminder function to remind participants who downloaded the app to fill out the questionnaire utilizing the (local notification) advantage in the Apple operating system, which allows the app to push the reminder even if the app is not running. When a user downloads the app and runs it for the first time, a random ID number is automatically assigned to the user's unique device identifier and is linked to the questionnaire in order to uniquely identify each participant. The questionnaire and usage data were saved on the devices and synchronized automatically to the research database whenever an internet connection is available. No identification or contact data were collected through the app. To avoid the problem of missing data, participants could not submit their answers before completing all questions. This study was approved by the research ethics committee at King Saud University.

Figure 1:

Depression Monitor screenshots.

Participants

Consumers at the Apple App Store aged 18 and above were recruited passively over 4 months (September 2012–January 2013). Participants downloaded this study app after agreeing to the terms and conditions of use, which included the participants’ information and a consent agreement. We summarized the consent and participants’ information in the app download page and also included it inside the app in the ‘about’ section to make it easier for the participants to find it if needed. After the release of the app on the App Store, it was featured within the ‘Health and Fitness’ categories in the USA and the UK, and this led to a massive increase in the number of downloads, boosting the app's overall rank14 in other countries. This was unintended and unpreventable, as the app-featuring criteria are not published on the App Store, and app publishers are not informed if their app is being featured.

Data analysis

To determine the depression prevalence in our sample, we used two PHQ-9 thresholds recommended in the literature. The first threshold is a score of 11 and above, which in pooled estimates of 10 studies had the best trade-off between sensitivity, 0.89 (95% CI 0.75 to 0.96), and specificity, 0.89 (95% CI 0.79 to 0.94).15 The second threshold is a score of 15 and above, which has shown the highest specificity at 0.96 (95% CI 0.94 to 0.97).15 The Charlson comorbidity index was used to collect physical comorbidities.16 Finally, anxiety was briefly measured using the one Likert-scale question that has a strong correlation with the Spielberger State Trait Anxiety Inventory and the Social Phobia Inventory.17,18

RESULTS

Uptake

In 4 months, 8241 participants from 66 countries downloaded the app. Of those who downloaded it, 6089 completed the questionnaire, with an overall response rate of 73.9%. The highest download rates were from the USA, Australia, and the UK. The download numbers and response rates for each country are shown in table 1.

Table 1:

The download numbers and response rates for each country

| Country | No. of downloads | No. of completed questionnaires | Country | No. of downloads | No. of completed questionnaires |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | 2045 | 1567 | Mauritius | 4 | 1 |

| Australia | 2034 | 1644 | Belgium | 3 | 3 |

| UK | 1646 | 1115 | Greece | 3 | 3 |

| Canada | 1323 | 1027 | Iraq | 3 | 2 |

| Singapore | 279 | 152 | Isle of Man | 3 | 3 |

| New Zealand | 163 | 133 | Norway | 3 | 2 |

| Malaysia | 140 | 57 | Pakistan | 3 | 3 |

| Ireland | 115 | 78 | Paraguay | 3 | 2 |

| Kuwait | 56 | 25 | Poland | 3 | 3 |

| Brazil | 43 | 27 | Puerto Rico | 3 | 3 |

| Denmark | 36 | 28 | Taiwan | 3 | 1 |

| Saudi Arabia | 35 | 28 | Vietnam | 3 | 2 |

| United Arab Emirates | 30 | 20 | Albania | 2 | 2 |

| China | 23 | 10 | Costa Rica | 2 | 0 |

| Hong Kong | 23 | 10 | Guam | 2 | 1 |

| Korea | 22 | 11 | Iran | 2 | 2 |

| Philippines | 21 | 12 | Morocco | 2 | 2 |

| Sweden | 21 | 15 | Russian Federation | 2 | 2 |

| Germany | 19 | 14 | Serbia | 2 | 2 |

| Mexico | 12 | 9 | South Africa | 2 | 2 |

| the Netherlands | 12 | 8 | Ukraine | 2 | 0 |

| Austria | 9 | 7 | Bangladesh | 1 | 1 |

| France, French Republic | 9 | 7 | Bermuda | 1 | 0 |

| Thailand | 8 | 5 | Chile | 1 | 1 |

| Japan | 7 | 7 | Croatia | 1 | 1 |

| Spain | 7 | 5 | Cyprus | 1 | 1 |

| India | 6 | 3 | Egypt | 1 | 1 |

| Portugal, Portuguese Republic | 6 | 0 | Fiji, the Fiji Islands | 1 | 1 |

| Turkey | 6 | 2 | Finland | 1 | 1 |

| Indonesia | 5 | 4 | Qatar | 1 | 1 |

| Italy | 5 | 2 | Romania | 1 | 1 |

| Bahrain | 4 | 2 | Sri Lanka | 1 | 1 |

| Israel | 4 | 3 | Venezuela | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 8241 | 6089 |

Demographics and health status

Of the total respondents (n = 6089), the mean age was 29.4 years (SD 10.8). The range was 18–72 years, and the median age was 26 years. However, 70% of participants in all countries were from the 18–34 age group. Most participants had a maximum education level of high school completion (59.1%), but 19.4% had completed graduate school as their highest educational achievement. More women (57.8%) than men participated in this study; 25.7% of the participants had previously been diagnosed with depression, and 26.3% of the participants with one or more physical comorbid conditions. The most common physical comorbid condition was asthma at 51.2%.

Depression screening

Of those who had not previously been diagnosed with depression, 82.5% were at high risk of depression using a PHQ-9 threshold of 11,while 66.8% were at high depression risk if a threshold of 15 was used (n = 4522). Table 2 shows the prevalence of higher depression risk among participants from the top six countries. Of those identified as higher risk using the PHQ-9 thresholds of 11 and 15, 36.0% and 34.8%, respectively, responded ‘nearly every day’ to ‘thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way’ (PHQ-9 suicidal ideation statement Item 9). Those with a higher number of comorbidities were more likely to have been previously diagnosed with depression than those not previously diagnosed but identified at higher risk of depression at cut-off 11 (t(5297) = 12.2; p = 0.001). A logistic regression model including age, gender, country, education level, anxiety, alcohol consumption, and substance use revealed that postgraduate education level (OR: 2.7; 95% CI 2.1 to 3.6), graduate educational level (OR: 1.7; 95% CI 1.5 to 2.0), and increased number of comorbidities (OR: 1.6; 95% CI 1.5 to 1.8) were significantly associated with being previously diagnosed with depression compared to those who were undiagnosed yet at higher risk of depression using a PHQ-9 threshold of 11.

Table 2:

Country-based prevalence of undiagnosed higher risk depression using PHQ-9 thresholds of 11 and 15

| Country |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia n (%) |

USA n (%) |

UK n (%) |

Canada n (%) |

Singapore n (%) |

New Zealand n (%) |

Total n (%) |

|

| Cut-off 11 | |||||||

| At risk of depression | 1092 (86.9) | 868 (79.3) | 666 (83.2) | 674 (84.9) | 63 (45.3) | 83 (82.2) | 3446 (82.3) |

| Not at risk | 165 (13.1) | 226 (20.3) | 134 (16.8) | 120 (15.1) | 76 (54.7) | 18 (17.8) | 739 (17.7) |

| Cut-off 15 | |||||||

| At risk of depression | 890 (70.8) | 710 (64.9) | 542 (67.8) | 532 (67.0) | 43 (30.9) | 67 (66.3) | 2784 (66.5) |

| Not at risk | 367 (29.2) | 384 (35.1) | 258 (32.2) | 262 (33.0) | 96 (69.1) | 34 (33.7) | 1401 (33.5) |

On the other hand, 60.2% of participants also had moderate or high anxiety within the group identified with potential depression yet undiagnosed at a threshold of 11, and 51.5% at a threshold of 15.

App usage

The proportion of participants who completed the PHQ-9 questionnaire more than once was 43.4%, with an average number of 2.7 and a range between 1 and 88 times. When excluding the number of participants who completed the questionnaire once, the average number of completions was 5.3 times. However, the average number of times the app was launched by each participant was 3.2, with a range between 1 and 141 times (average excluding one-time users was 5.9 times). A χ2 test for independence indicated significant associations between the frequency of completing the PHQ-9 questionnaire and: education levels, χ (3, n = 6089) = 9.6, p = 0.02; previous depression diagnosis, χ (1, n = 6089) = 31.4, p = 0.00; anxiety, χ (4, n = 6089) = 12.3, p = 0.01; and risk of depression (obtained from the first recorded score) at cut-off 11, χ (1, n = 6089) = 16.0, p = 0.001, and cut-off 15, χ (1, n = 6089) = 10.9, p = 0.001. Further logistic regression analysis, including age, gender, education, previous depression diagnosis, anxiety, and risk of depression at both PHQ-9 thresholds, found that a PHQ-9 score of higher than 11, a previous diagnosis of depression, and a postgraduate educational attainment were significantly associated with multiple PHQ-9 completions (table 3).

Table 3:

Variables associated with completing the PHQ-9 questionnaire more than once

| OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Risk of depression at cut-off 11 | 1.4 | 1.2 to 1.6 |

| Previous depression diagnosis | 1.3 | 1.2 to 1.5 |

| Postgraduate educational level | 1.2 | 1.0 to 1.5 |

DISCUSSION

In this study, 8241 users from Apple's App Store downloaded our ‘Depression Monitor’ app from 66 countries. Of them, 6089 participants submitted the questionnaire included in this paper's analysis. More than 70% of participants in all countries were younger adults. Of the participants, 25.7% had been previously diagnosed with depression. There were a large number of participants with a higher risk of depression yet undiagnosed using both thresholds of the PHQ-9 depression screening tool. The study app also reached various groups of people who had not previously been diagnosed with depression yet had a higher risk, had one or more physical comorbid conditions, or had high levels of anxiety. In addition, the app was able to reach a group of participants who were at risk of suicide. Higher educational level and a higher number of physical comorbidities were associated with a previous depression diagnosis compared to those undiagnosed yet at higher risk of depression using a PHQ-9 threshold of 11.

This study used a well-validated self-administered depression screening test (PHQ-9) and two thresholds that have shown a very high level of sensitivity and specificity in previous studies.15 However, although the positive likelihood ratios for PHQ-9 at the thresholds are high,15 false positive and negative results should not be overlooked. Our depression screening findings were similar to other studies in the general population.19 Like ours, other studies have found that higher education level was associated with depression having been diagnosed.20

We note the positive association between the number of times the questionnaire was completed and a higher risk score, which may be related to the immediacy of app feedback, however this phenomenon deserves further exploration to understand how and why people use mental health apps. For example, we note that a high number of participants only completed the test once. It may be that their low severity score had reassured them that they did not need further evaluation or to use the app again.

In a recent study, responses to Item 9 of the PHQ-9 were a strong predictor of suicide attempts.21 About one third of app users with a PHQ-9 greater than 15 answered ‘nearly every day’ to the PHQ-9 suicidal ideation statement (Item 9), which shows that smartphone depression screening can reach those at risk of suicide and may be useful to target them for interventions to prevent suicide.

This study has shown that a large number of people from different countries were searching for, and willing to use, a depression screening app. It has also shown that many people were willing to share sensitive data about their health through a secure and anonymous smartphone app. Nevertheless, there is very limited evidence for the efficacy of smartphone-delivered mental health interventions.22 The limited number of studies conducted in this area might be due to the lack of feasibility and confidence that these interventions will reach the targeted populations. However, this study deliberately recruited participants via the typical way smartphone users will seek apps and provided new evidence that smartphone mental health interventions are sought and used by relevant users.

This study has also shown that smartphone apps can be used efficiently as a health research tool. We implemented a reminder function for participants to fill out the questionnaire, and it is possible that this reminder might have had an effect on the response rate in this study (73.9%), compared to a study with a similar recruitment method without a reminder, with a response rate of 37%.23

These results were limited by the nature of the self-selected sample, as participants who knew that they were at risk of depression might be more motivated to take the test than others. However, this did not affect the fact that a high proportion of them had a higher risk of depression and were untreated. Another limitation is that the app was only released in English, which limited the app downloads to mainly English-speaking populations.

CONCLUSION

This study showed that depression screening tools can be delivered via smartphone apps, showing the future potential for this approach in screening and self-monitoring of depression. A large number of consumers were willing to use our app, possibly due to its convenient accessibility and simplicity of use for those at risk of mental health problems.

CONTRIBUTORS

All authors made substantial contributions to editing and drafting of the manuscript. NFB, AMS, and TMA were responsible for conceptual development and study design. NFB and MHB were responsible for the screening app development, design, and data collection. NFB and TMA were responsible for data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS

None.

ETHICS APPROVAL

This study was approved by the research ethics committee at King Saud University.

PROVENANCE AND PEER REVIEW

Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.BinDhim NF, Freeman B, Trevena L. Pro-smoking apps for smartphones: the latest vehicle for the tobacco industry? Tob Control 2014;23:e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackay M. Australian mobile phone lifestyle index. 2012. http://www.aimia.com.au/getfile?id=4422&file=AMPLI+2012+Report_FINAL_September+17.pdf

- 3.Deloitte. Exponential rise in consumers’ adoption of the smartphone—can retailers keep pace?. 2013. [12/02/2014]. http://www.deloitte.com/view/en_GB/uk/61d116116757f310VgnVCM1000003256f70aRCRD.htm

- 4.Blackbox Research. Smartphones in Singapore: a Whitepaper. 2013. [22/01/2014]. http://www.blackbox.com.sg/wp/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Blackbox-YKA-Whitepaper-Smartphones.pdf

- 5.Nielsenwire. Consumer Electronics Ownership Blasts Off in 2013. 2013. [21/02/2014]. http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/newswire/2013/consumer-electronics-ownership-blasts-off-in-2013.html

- 6.Torous J, Friedman R, Keshvan M. Smartphone ownership and interest in mobile applications to monitor symptoms of mental health conditions. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2014;2:e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kauer DS, Reid CS, Crooke DAH, et al. Self-monitoring using mobile phones in the early stages of adolescent depression: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2012;14:e67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris EM, Kathawala Q, Leen KT, et al. Mobile therapy: case study evaluations of a cell phone application for emotional self-awareness. J Med Internet Res 2010;12:e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.BinDhim NF. Health monitor project. 2012. [26/01/2014]. http://shproject.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=3

- 10.Allgaier A-K, Pietsch K, Frühe B, et al. Screening for depression in adolescents: validity of the patient health questionnaire in pediatric care. Depress Anxiety 2012;29:906–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phelan E, Williams B, Meeker K, et al. A study of the diagnostic accuracy of the PHQ-9 in primary care elderly. BMC Fam Pract 2010;11:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richardson LP, McCauley E, Grossman DC, et al. Evaluation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Item for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics 2010;126:1117–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fann JR, Berry DL, Wolpin S, et al. Depression-screening using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 administered on a touch screen computer. Psychooncology 2009;18:14–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.BinDhim NF, Freeman B, Trevena L. Pro-smoking apps: where, how and who are most at risk. Tob Control 2013. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manea L, Gilbody S, McMillan D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): a meta-analysis. CMAJ 2012;184:E191–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.BinDhim NF, Shaman AM, Alhawassi TM. Confirming the one-item question Likert Scale to measure anxiety. Internet J Epidemiol 2013;11. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davey HM, Barratt AL, Butow PN, et al. A one-item question with a Likert or Visual Analog Scale adequately measured current anxiety. J Clin Epidemiol 2007;60:356–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Houston TK, Cooper LA, Vu HT, et al. Screening the public for depression through the Internet. Psychiatr Serv 2001;52:362–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bertakis KD, Helms LJ, Callahan EJ, et al. Patient gender differences in the diagnosis of depression in primary care. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 2001;10:689–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simon GE, Rutter CM, Peterson D, et al. Does response on the PHQ-9 depression questionnaire predict subsequent suicide attempt or suicide death? Psychiatr Serv 2013;64:1195–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donker T, Petrie K, Proudfoot J, et al. Smartphones for smarter delivery of mental health programs: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.BinDhim FN, McGeechan K, Trevena L. Who uses smoking cessation apps? a feasibility study across three countries via smartphones. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2014;2:e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]