Abstract

Recent technology for chronic electrical activation of the carotid baroreflex and renal nerve ablation provide global and renal-specific suppression of sympathetic activity, respectively, but the conditions for favorable antihypertensive responses in resistant hypertension are unclear. Because inappropriately high plasma levels of aldosterone are prevalent in these patients, we investigated the effects of baroreflex activation and surgical renal denervation in dogs with hypertension induced by chronic infusion of aldosterone (12µg/kg/day). Under control conditions, basal values for mean arterial pressure and plasma norepinephrine concentration were 100±3 mm Hg and 134±26 pg/mL, respectively. By day 7 of baroreflex activation, plasma norepinephrine was reduced by ~ 40% and arterial pressure by 16±2 mmHg. All values returned to control levels during the recovery period. Arterial pressure increased to 122±5 mm Hg concomitant with a rise in plasma aldosterone concentration from 4.3±0.4 to 70.0±6.4 ng/dL after 14 days of aldosterone infusion, with no significant effect on plasma norepinephrine. After 7 days of baroreflex activation at control stimulation parameters, the reduction in plasma norepinephrine was similar but the fall in arterial pressure (7±1 mmHg) was diminished (~ 55%) during aldosterone hypertension as compared to control conditions. Despite sustained suppression of sympathetic activity, baroreflex activation did not have central actions to inhibit either the stimulation of vasopressin secretion or drinking induced by increased plasma osmolality during chronic aldosterone infusion. Finally, renal denervation did not attenuate aldosterone hypertension. These findings suggest that aldosterone excess may portend diminished blood pressure lowering to global and especially renal-specific sympathoinhibition during device-based therapy.

Keywords: arterial pressure, aldosterone, baroreflex, sympathetic nervous system, renal nerves, renal function, vasopressin

Introduction

Recent technology for chronic electrical activation of the carotid baroreflex (BA) and renal nerve ablation provide global and renal specific suppression of sympathetic activity, respectively, and has been under investigation for the treatment of resistant hypertension.1–5 These non-pharmacological approaches for the management of resistant hypertension reduce arterial pressure in some but not in all patients in this heterogeneous hypertensive population. The reasons for this variability are not well understood. One possible explanation is that secondary causes of hypertension, including primary aldosteronism, are common in patients with resistant hypertension.6–9 While diagnosed primary aldosteronism is an exclusion condition for eligibility in clinical trials using device-based therapy, the proportion of patients normally screened for this is unclear and the effect of this on the clinical outcomes of the trials is not fully characterized.10 Furthermore, because many patients with resistant hypertension have intravascular volume expansion, even modestly elevated or even normal levels of aldosterone are believed to be inappropriately high and likely to contribute to the volume overload state, despite the requirement for diuretic use in these trials.6–9 In support of this hypothesis, when added to standard therapy the aldosterone antagonist spironolactone has produced further reductions in arterial pressure in resistant hypertensive patients with and without documented hyperaldosteronism.6–14 Even with this understanding, data from the NHANES from 2003 through 2008 indicate that only ~3% of patients in the United States with resistant hypertension were treated with spironolactone,15 and it was not widely used in recent clinical trials using device-based therapy for the treatment of resistant hypertension.1–5,10 Thus, the effectiveness of these medical devices for treating resistant hypertension when absolute or relative aldosterone excess contributes significantly to the hypertension is unknown.

Because sympathetic activity is increased in many with resistant hypertension,16 it is reasonable to expect a reduction in arterial pressure when sympathoinhibitory treatments are used. However, it is likely that a variable degree of sympathetic activity is a major factor in the inconsistent arterial pressure response to device-based therapy. Another likely determinant of the antihypertensive effects of device-based therapy is renal function, although the impact of basal levels of renal function on blood pressure lowering and the ensuing changes in renal function have received little attention. In this context, we previously reported that along with chronically suppressing the sympathetic overactivity and hypertension of obesity in dogs, BA attenuated the associated glomerular hyperfiltration.17 We attributed the antihypertensive effects of BA, in part, to inhibition of neurally-mediated sodium reabsorption prior to the macula densa, which we theorized also provided renal protection by reducing glomerular filtration rate (GFR) through increased tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF). Primary aldosteronism is another form of hypertension associated with hyperfiltration. However, unlike obesity-related hypertension, evidence suggesting sympathetic activation in aldosterone hypertension is equivocal.18–22 Therefore, if the sympathetic nervous system is not activated in aldosteronism and BA lowers arterial pressure by suppressing central sympathetic outflow, we hypothesized that antihypertensive and renal hemodynamic responses to BA would be diminished in aldosterone hypertension. Further, because the chronic blood pressure lowering effects of BA are not exclusively dependent on renal innervation,3,23 we hypothesized that the antihypertensive effects of BA in aldosterone hypertension would exceed those of renal denervation. Finally, although it is well established that the carotid baroreflex has acute effects on vasopressin (AVP) secretion and drinking,24–25 we determined whether chronic electrical stimulation of carotid baroreceptor afferents has actions in the brain to not only suppress central sympathetic outflow but to also suppress the normal compensatory increases in AVP secretion and drinking that occur in response to the hyperosmolality associated with aldosteronism.

Methods

Animal Preparation

All experimental protocols were performed according to the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” from the National Institutes of Health and approved by the University of Mississippi Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Surgical procedures were conducted under isoflurane anesthesia (1.5% to 2.0%) after premedication with acepromazine (0.15 mg/kg, SC) and induction with thiopental (10 mg/kg, IV). Carprofen (Ramadyl), 4 mg/kg, was administered for 3 days postoperatively for analgesia.

Experiments were conducted in 9 chronically instrumented mongrel dogs weighing 22.0 to 25.8 kg. As previously described,26–28 arterial and venous catheters were implanted for continuous measurement of arterial pressure and for blood sampling, and for continuous intravenous isotonic saline infusion, respectively. In a second surgery, a second generation miniaturized electrode (Barostim Neo) was sutured to the surface of each carotid sinus and the lead bodies were tunneled subcutaneously and connected to a pulse generator implanted in the chest. The electrodes and the pulse generator for electrical stimulation of the carotid sinuses were provided by CVRx, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN).

See the online only Data Supplement for General Methods.

Experimental Protocol

After the 3–4 week period of acclimation when electrolyte and fluid balance were achieved, steady-state control measurements were made. The sequential experimental protocol for all 9 animals was as follows: 1) control, 2) BA-7 days, 3) recovery-10 days, 4) aldosterone infusion-14 days, 5) continued aldosterone infusion + BA-7 days, and 6) continued aldosterone infusion-4 days (recovery from BA).

During the initial 7 days of BA (2 above), the pulse generator was programmed to deliver constant, continuous energy using the following parameters: 3–6 mA, 30 Hz, and 0.5-ms pulse duration. The intensity of activation was selected by adjusting the current to achieve a chronic decrease in MAP of ~15 mmHg. To achieve this goal, small adjustments in current were needed during the first 24–48 hours, but no changes in the intensity of activation were made after the first 48 hours of stimulation. Subsequently, the same stimulation parameters were used during aldosterone hypertension (5 above). To produce aldosterone hypertension, aldosterone (Sigma) was infused at a rate of 12 µg/kg/day by adding the steroid to the continuous IV saline infusion.

On the last 2 days of the above protocols, arterial blood samples (~10 ml) were taken while the dogs were recumbent and in a resting state. In addition, GFR was measured on the last day of each protocol. Finally, after completing the above protocols, 3 of the dogs were subjected to an additional 28 days of aldosterone infusion with bilateral renal denervation17,23 after 14 days of hypertension. To verify completeness of renal denervation, renal cortical samples for tissue norepinephrine (NE) concentration were taken ~ 1 week after terminating the 28 day period of aldosterone infusion.

Analytical Methods

The daily hemodynamic values for mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate were averaged from the 20-hour period extending from 11:30-7:30 AM.28 The data excluded from the 24-hour recordings comprised the time required for flushing catheters, calibrating pressure transducers, feeding, and cleaning cages.

Plasma renin activity (PRA) and the plasma concentrations of aldosterone were measured by radioimmunoassay in the Departmental Core facility;26–28 radioimmunoassay of plasma AVP was conducted in the laboratory of Willis K. Samson. Plasma NE concentrations and renal tissue levels of NE were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with electrochemical detection in the laboratory of Dr. David S. Goldstein. Hematocrit and the plasma concentrations of sodium, potassium, and protein, and the sodium and potassium concentrations in the daily 24-h urine samples were measured by standard techniques. GFR and sodium iothalamate space (an index of extracellular fluid volume) were determined from the clearance of 125I-iothalamate.29

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean±SEM. One-way, repeated measures ANOVA followed by the Dunnett post hoc t test for multiple comparisons was used to compare temporal changes in MAP and heart rate during BA to preceding control values before and after induction of aldosterone hypertension. A similar analysis was used to compare temporal changes in MAP and heart rate after renal denervation in 3 of the 9 dogs. In addition, the 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for changes in MAP after renal denervation using random intercept Linear Mixed Models. Within and between group neurohormonal responses to aldosterone infusion and BA were compared by the Bonferroni post hoc t test following two-way, ANOVA. Statistical significance was considered to be P<0.05.

Results

Responses to BA in the Normotensive State

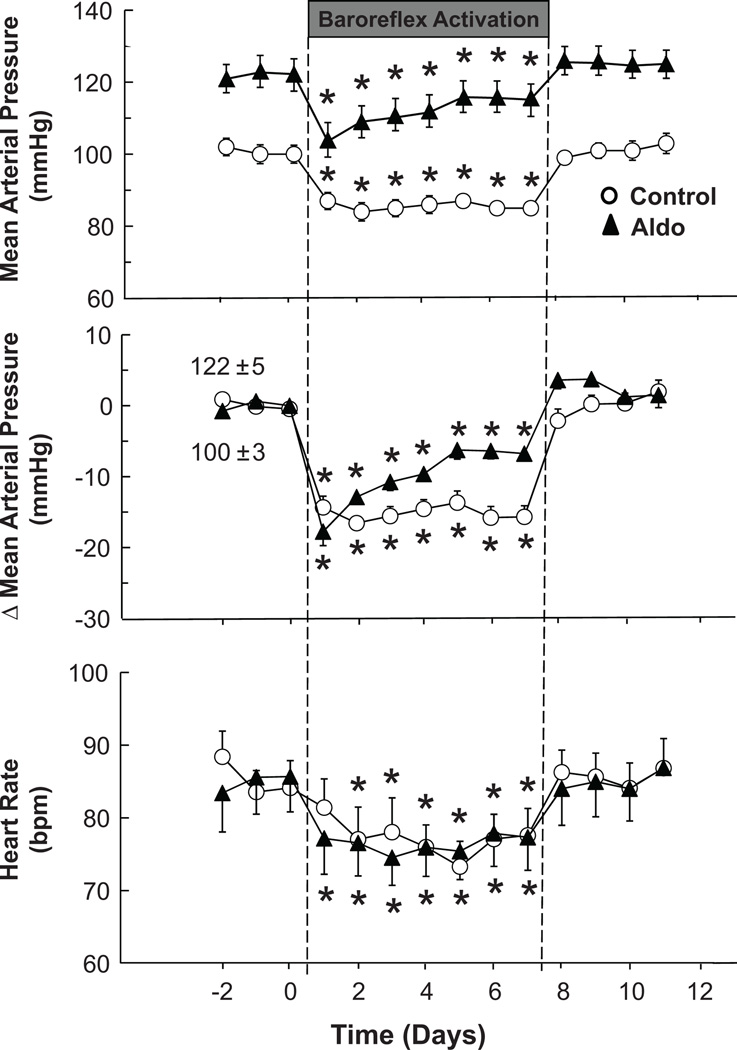

The chronic hemodynamic and urinary electrolyte responses to BA in the control state were similar to those reported previously.26–28 Control values for MAP and heart rate were 100±3 mmHg and 84±3 bpm, respectively. MAP and heart rate were stable from days 2–7 of BA and on day 7 of BA were reduced by 16±2 mmHg and 6±2 bpm, respectively, before returning to control levels by day 1 of the recovery period (Figure 1). Control excretion rates of sodium and potassium were 67±3 and 45±2 mmol/d, respectively, reflecting the intake of these electrolytes. As reported previously,26–28 during the first 48 hours of BA, coinciding with the fall in MAP, there was modest sodium retention (~ 35 mmol) before sodium balance was again achieved. This modest sodium retention did not produce a measureable change in extracellular fluid volume (sodium iothalamate space), as indicated in the Table. Retained sodium was excreted during day 1 of the recovery period. There were no significant changes in potassium excretion during BA.

Figure 1.

Effects of prolonged baroreflex activation on mean arterial pressure and heart rate before and after the induction of aldosterone hypertension. Values are mean ±SEM (n=9). * P<0.05 versus before baroreflex activation; bpm indicates beats per minute.

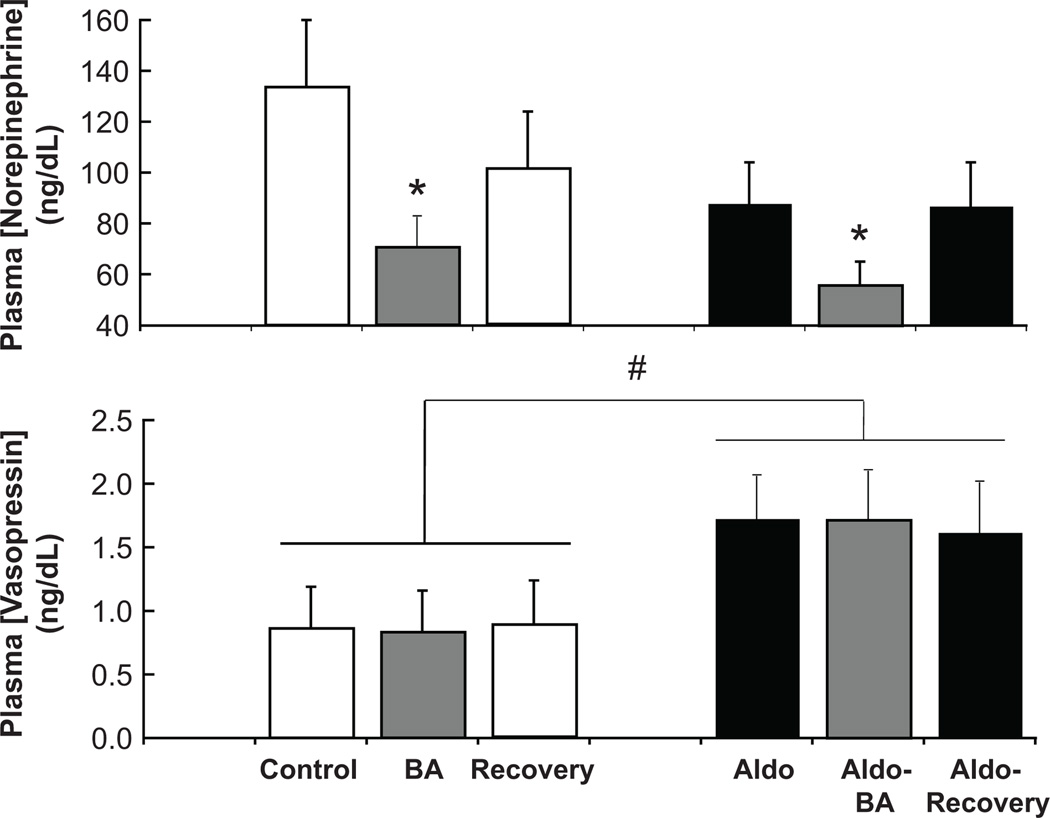

Neurohormonal responses to BA are shown in Figure 2 and in the Table. BA was associated with ~ a 40% reduction in plasma NE concentration (control=134±26 pg/mL), indicating sustained suppression of central sympathetic outflow. Despite this suppression, BA did not inhibit AVP secretion, nor were there significant changes in either PRA or plasma aldosterone concentration during BA, despite the reduction in MAP.

Figure 2.

Effects of prolonged baroreflex activation on the plasma concentrations of norepinephrine and vasopressin before and after induction of aldosterone hypertension, and the effects of aldosterone infusion on these neurohormonal variables. Values are mean ±SEM (n=9). * P<0.05 versus before baroreflex activation; # P<0.05 versus before aldosterone infusion.

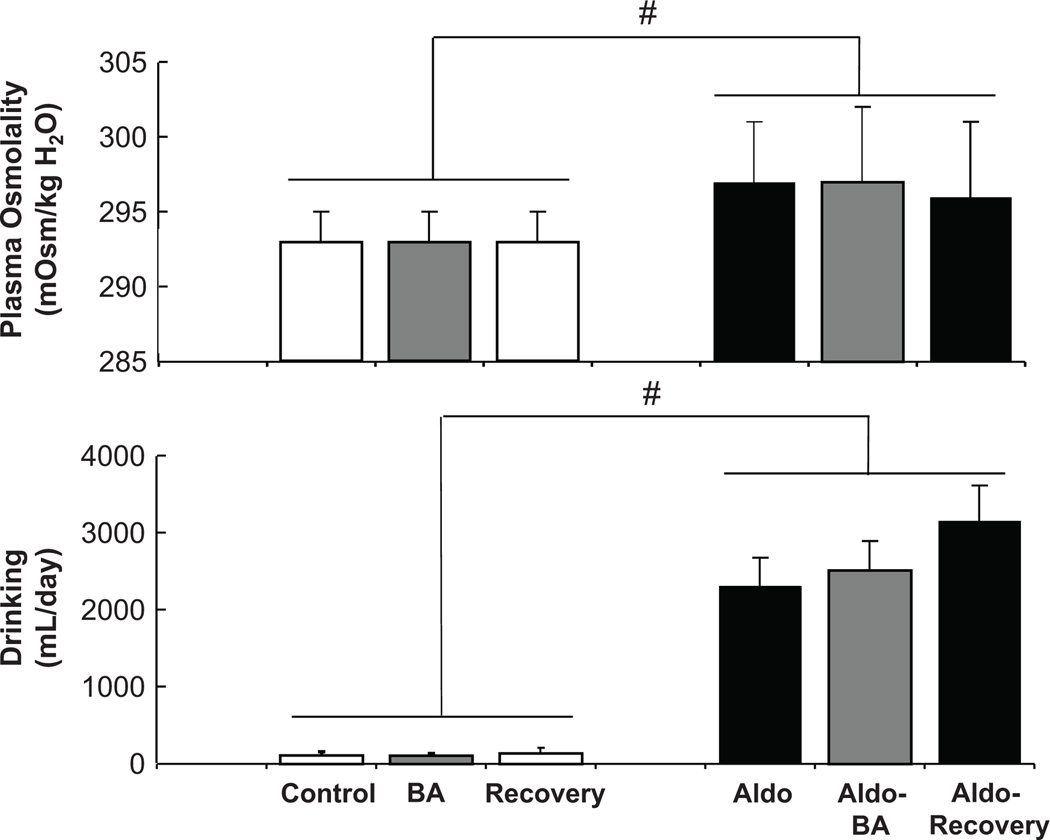

There were no significant changes in plasma osmolality, drinking, GFR, or plasma electrolyte concentration, during BA (Figure 3 and Table). However, in parallel with the modest fluid retention on day 1, hematocrit decreased from 41±1 to 38±1 during BA, without significant changes in plasma protein concentration (control=5.9±0.2 g/dL).

Figure 3.

Effects of chronic aldosterone infusion on plasma osmolality and drinking. Prolonged baroreflex activation had no effect on these variables either before or after induction of aldosterone hypertension. Values are mean ±SEM (n=9). # P<0.05 versus before aldosterone infusion.

Responses to Aldosterone Infusion

Aldosterone infusion produced the expected changes. During the first 3 days of aldosterone infusion, ~ 70 mmol of sodium were retained before daily sodium balance was achieved. As a result, there was an increase in extracellular fluid volume of ~ 500mL (Table) and a gradual increase in MAP of 20±3 mmHg before stabilizing after ~ 10 days. There was no significant change in heart rate. Potassium excretion increased (~20 mmol) above control levels during day 1 of aldosterone infusion before returning to control levels.

During aldosterone infusion, plasma aldosterone concentration increased ~ 15-fold (Table), to a level seen in dogs after 2 weeks on a low sodium intake.30 As expected, PRA decreased to undetectable levels and there were small (1.5–2%) but statistically significant increases in plasma sodium concentration and plasma osmolality, and marked hypokalemia (Figure 3 and Table). In addition, a 2-fold increase in plasma AVP concentration and a large increase in daily water intake were associated with the increase in plasma osmolality. Plasma NE concentration tended to be lower during aldosterone infusion, but this response was not statistically significant.

GFR increased substantially (20–25%) during aldosterone infusion. Despite fluid retention, there were no significant changes in either hematocrit (preinfusion=43±1) or plasma protein concentration (preinfusion=5.9±0.2 g/dL) after 2 weeks of the infusion.

Responses to BA in Aldosterone Hypertension

During aldosterone hypertension, reductions in MAP on day 1 of BA were comparable to those in the control state, but long-term changes were substantially different (Figure 1). In contrast to the sustained lowering of MAP in the control state, the response in aldosterone hypertension was appreciably diminished with the final day MAP reduction being 7±1 versus 16±2 mmHg under control conditions. Thus, during aldosterone hypertension, the blood pressure lowering response to BA was attenuated ~ 55%. In contrast to the MAP response, BA-induced bradycardia was sustained and equivalent to that achieved under control conditions (Figure 1). After cessation of BA and during continued aldosterone infusion, MAP and heart rate increased to levels not significantly different from day 14 of aldosterone hypertension. The urinary electrolyte excretion responses to BA in aldosterone hypertension were similar to those in the control state. On the first day of BA, ~ 25 mmol of sodium were retained before daily sodium balance was reestablished on the following days. As in the control state, BA had no significant effect on urinary potassium excretion.

Other than producing a reduction in plasma NE concentration similar to that seen under control conditions, BA had no significant effect on measured hormones, body fluids and electrolytes, and GFR (Figures 2 and 3, Table). Most notably, although suppressing central sympathetic outflow, BA did not diminish the osmotic stimulation of AVP secretion and drinking.

Responses to Renal Denervation in Aldosterone Hypertension

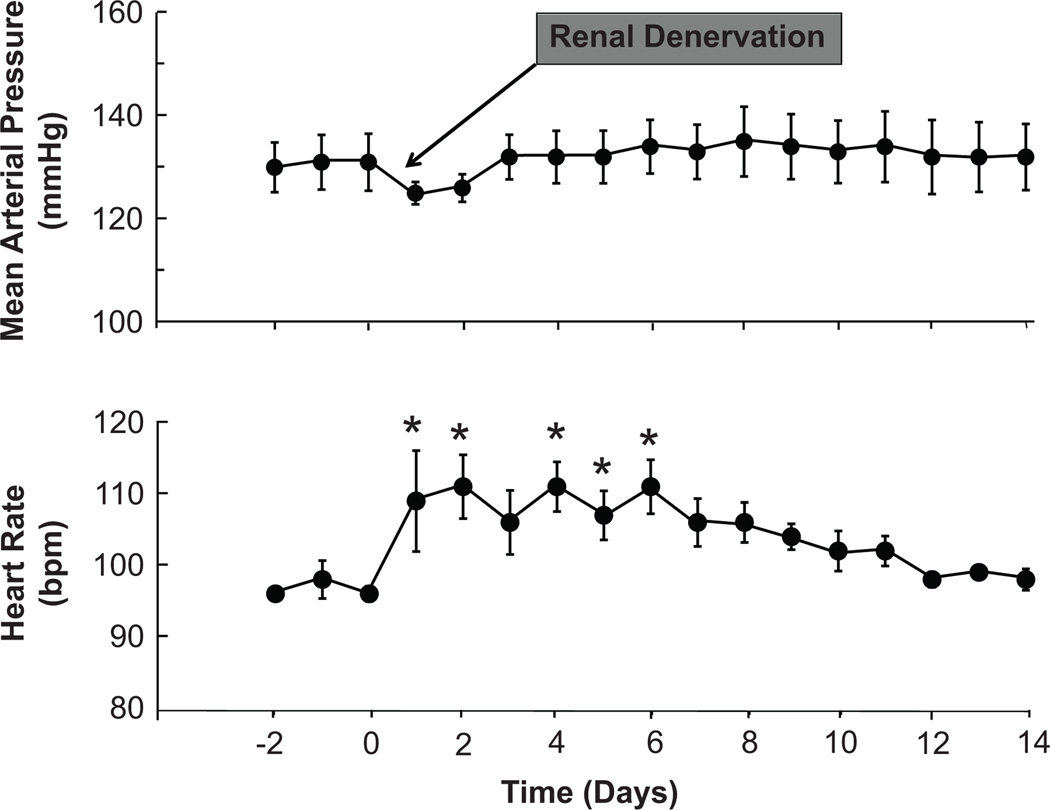

Figure 4 illustrates the arterial pressure and heart response to bilateral renal denervation in 3 dogs with aldosterone hypertension. Following day 3 of renal denervation, there were no statistically significant changes in MAP from pre-operative levels in these 3 dogs, but modest transient increases in heart rate did persist during the first post-operative week. The mean change in MAP (95% CI) comparing days 3–14 after renal denervation to the 3 days of aldosterone hypertension preceding renal denervation was +2.00 (−0.04, 4.04) mmHg. Because renal denervation failed to chronically lower MAP in these 3 dogs, no additional animals were subjected to renal denervation and studied for the additional 28 days required to complete the renal denervation protocol.

Figure 4.

Effects of bilateral surgical denervation on mean arterial pressure and heart rate in aldosterone hypertension. Values are mean ±SEM (n=3). * P<0.05 versus before renal denervation.

Renal Tissues Levels of NE2

In the 6 denervated kidneys (3 dogs), renal cortical NE concentration was 2±1 pg/mg, which is comparable to the levels we have reported previously in dogs with denervated kidneys.17,23 In these two previous studies, tissue levels of NE in innervated kidneys were 564±113 and 987±80 pg/mg renal cortex.17,23 Thus, the measured levels of NE in the denervated kidneys of the present study reflect the completeness of renal denervation.

Discussion

This study has several novel findings. First, despite sustained suppression of sympathetic activity, the chronic blood pressure lowering effects of BA were attenuated in the presence of hypertension induced by the high circulating levels of aldosterone normally associated with low sodium intake.30 Second, renal denervation was completely devoid of antihypertensive effects in aldosterone hypertension. Third, pressure lowering by BA in aldosterone hypertension occurred without changes in GFR. Fourth, although having sustained effects to suppress sympathetic activity, BA did not have central actions to inhibit the compensatory increases in AVP secretion and drinking that normally minimize increases in plasma osmolality during aldosterone excess. These findings add to our understanding of the variable antihypertensive responses seen in trials of device-based therapy for resistant hypertension and suggest aldosteronism may portend a diminished antihypertensive response to global and especially renal-specific inhibition of sympathetic activity and that the renal protection associated with baroreflex-mediated blood pressure lowering is initially independent of functional responses that diminish hyperfiltration.

Infusion of aldosterone in this study led to physiological responses commonly seen in subjects with primary aldosteronism: hypertension, expansion of extracellular fluid volume, glomerular hyperfiltration, hypokalemia, modest hypernatremia, and suppression of PRA. The initial sodium retention leading to volume expansion (increased sodium iothalamate space) indicates that aldosterone-induced hypertension is the result of the classic effects of the mineralocorticoid to promote sodium reabsorption in the late distal tubule and cortical collecting tubule. Another proposed mechanism of mineralocorticoid-induced hypertension is activation of the sympathetic nervous system. The data on this are conflicting with most of the support for this hypothesis coming from experimental models in which deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA) or aldosterone are chronically infused subcutaneously or directly into the cerebral ventricles in rats given only isotonic or hypertonic saline to drink following unilateral nephrectomy.31 However, the physiological relevance of these studies is questionable, with the limitations of this model cogently articulated by Geerling and Loewy.21 Furthermore, whereas the above traditional DOCA-salt model in the rat produces substantial hypertension and target organ damage within weeks, a recent study reported that when both kidneys are present and lower doses of DOCA are administered subcutaneously to produce a more gradual moderate increase in arterial pressure, the resultant hypertension is actually associated with suppression of whole body NE spillover and an inability of renal denervation to attenuate the hypertension.32 Furthermore, inhibition of sympathetic activity has also been reported following induction of mineralocorticoid hypertension in dogs, sheep, and humans.19,33–34 Of particular relevance to primary aldosteronism, several studies 18,20,35 but not all,22 have reported either normal or suppressed levels of sympathetic activity in this form of secondary hypertension. Also the present study does not provide statistically significant evidence to support the hypothesis of sympathetic activation in aldosterone hypertension, in fact, even showing a small statistically insignificant reduction in plasma levels of NE during aldosterone infusion. Taken together, the current data, along with the above findings of a number of experimental and clinical studies, fail to support the hypothesis that sympathoexcitation contributes to the hypertension induced by mineralocorticoid excess, at least within a time frame that does not lead to target organ damage. Rather, high circulating levels of aldosterone cause hypertension primarily by its well established actions to promote sodium retention and volume expansion.

The responses to BA in the control normotensive state were similar to those reported previously.26–28 Most notably, prolonged BA chronically suppressed sympathetic activity and lowered MAP to the target level throughout 7 days of BA. As in previous studies, PRA did not increase despite the fall in arterial pressure. Chronic suppression of renal sympathetic nerve activity (RSNA) likely inhibits pressure-dependent renin release during chronic BA, with neurally-mediated inhibition of the renin-angiotensin system appearing to play an important role in long-term blood pressure lowering,26,36 as discussed next.

The initial reductions in MAP in response to BA were comparable under control conditions and during aldosterone hypertension, reflecting primarily the effects of suppression of central sympathetic outflow on peripheral resistance, vascular capacity and cardiac function, while chronic arterial pressure lowering, which is dependent on more sluggish renal mechanisms,36 was very different. During aldosterone hypertension, the chronic reduction in MAP during BA was substantially reduced by ~55% as compared to control conditions. Because increased renal excretory function is a prerequisite for long-term reductions in arterial pressure, the dichotomy between the acute and chronic arterial pressure responses to BA suggests that regardless of whether sympathetic activity is unchanged from control levels or, as indicated above, possibly reduced in aldosterone hypertension, global suppression of sympathetic activity by BA has only modest effects to offset the antinatriuretic effects of high circulating levels of aldosterone that lead to increased arterial pressure. Similarly, the antihypertensive effects of BA are also markedly diminished in the chronic canine ANG II infusion model of hypertension, which is also not neurogenically mediated.26,36 In marked contrast to the ANG II and aldosterone infusion models of hypertension, both BA and renal denervation suppress PRA and abolish obesity-related hypertension in canines, which is mediated by activation of the sympathetic nervous system.17 Taken together, these findings suggest that the natriuretic response to BA, and the concomitant blood pressure lowering, is limited under conditions when RSNA is not increased and the components of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system are elevated and unable to respond to sympathoinhibition.

While the renal nerves do provide a logical link between BA induced reductions in central sympathetic outflow and increased renal excretory function that leads to chronic lowering of arterial pressure, experimental and clinical studies indicate that the presence of the renal nerves is not an obligate requirement for this effect.3,23 Also while renal denervation did not attenuate the severity of the aldosterone hypertension in the present study, BA did still have antihypertensive effects. Without chronic suppression of RSNA, the mechanisms that increase renal excretory capacity and lead to long-term reductions in arterial pressure during BA are unclear. In this regard, computer simulations of the circulatory system indicated greater activation of redundant natriuretic mechanisms during BA in the absence of the renal nerves.36–37 More specifically, the simulations identified increased secretion of atrial natriuretic peptide and increased renal interstitial pressure as two natriuretic mechanisms of increased importance in promoting sodium excretion in kidneys without renal innervation. However, the predictions from these theoretical analyses have not been validated in experimental studies.

There is little information on renal function in patients treated with device-based therapies with resistant hypertension as these studies have typically excluded patients with significant renal dysfunction, and changes in renal function have been assessed using serum creatinine-based estimates of GFR. In our experimental studies, the clearance of 125I-iothalamate was used to more precisely measure the changes in GFR in response to chronic BA. In our previous work in the canine model of obesity hypertension, BA chronically suppressed sympathetic overactivity, abolished the hypertension, and diminished the associated glomerular hyperfiltration.17 Based on these observations, we hypothesized that suppression of RSNA by BA increases sodium chloride delivery to the macula densa and, consequently, the signal to constrict the afferent arteriole. In contrast to this response in obese dogs, the lowering of arterial pressure during BA in the present study was not associated with a reduction in the hyperfiltration associated with aldosterone hypertension or a fall in GFR under control conditions. This is consistent with the above hypothesis because BA would not be expected to produce appreciable sustained increases in sodium chloride delivery to the macula densa without a baseline increase in neurally-mediated sodium reabsorption.

Acute pressure-induced alterations in baroreceptor activity have inverse effects on AVP secretion and drinking.24–25 However, experimental limitations have precluded a clear understanding of the importance of arterial baroreceptors in long-term nonosmotic control of these variables. In contrast to these acute observations, a novel finding in this study was that despite sustained inhibition of central sympathetic outflow, chronic stimulation of carotid baroreceptor afferents did not have central actions to diminish the osmotic stimulation of AVP secretion and drinking during aldosterone excess, actions that otherwise would have exacerbated the degree of hypernatremia.

Because long-term aldosterone excess has been reported to cause inflammation, fibrosis, and dysfunction in various organs including the heart and kidneys,38 a limitation of this study is its relatively short duration. Thus, we cannot discount the possibility that the current findings during BA may be different under more chronic conditions associated with aldosterone-mediated target organ damage.

Perspectives

By providing a better mechanistic understanding of the cardiovascular responses to global and renal specific sympathoinhibition, the current findings may help identify which phenotype best predicts a patient who will have a favorable arterial pressure response to device-based therapies that reduce sympathetic activity. The current findings support experimental and clinical studies indicating that aldosterone hypertension is volume dependent and is characterized by decreased sympathetic activity, at least in the early stages of the hypertension before there is significant target organ damage (including renal injury). They are also consistent with previous findings indicating that blood pressure lowering during global suppression of sympathetic activity by BA is not exclusively dependent on neurogenic mechanisms that target the renal nerves. Accordingly, because aldosterone excess is a common feature in resistant hypertension, these findings suggest that there may be diminished antihypertensive responses to BA and especially renal nerve ablation in these patients not treated with aldosterone antagonists. This supposition is consistent with a recent post hoc analysis from a cohort of patients in the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial indicating that prescription of an aldosterone antagonist at baseline was a positive predictor for a favorable antihypertensive response to renal nerve ablation.39 In the context of this analysis, it is important to note that the current findings and those from most clinical studies using device-based therapy have been limited to subjects with little or no impairment in renal function. However, because the presence of chronic kidney disease is a strong predictor of resistant hypertension and is a risk marker for increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in resistant hypertension,6,40 future clinical trials are needed to explore the safety and efficacy of device-based therapies in this patient population with reduced renal function. Because the adverse effects of aldosterone antagonists, including worsening renal function and hyperkalemia,11,13–14 may preclude their clinical use as antihypertensive agents in subjects with resistant hypertension and impaired renal function, the present findings suggest that the efficacy of device-based therapy may be limited under conditions when resistant hypertension is associated with aldosteronism and reduced GFR, but this hypothesis remains to be tested.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Absence of Renal and Hormonal Responses to Baroreflex Activation before and After Aldosterone Hypertension

| CONDITION | PRA (ng ANG I/ mL/hr |

PALDO (ng/dL) |

PNa (mmol/L) |

PK (mmol/L) |

GFR (mL/min) |

Na Iothal Space (mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CONTROL | 1.2±0.2 | 4.3±0.4 | 148±1 | 4.2±0.1 | 67±3 | 5489±160 |

| BA | 0.9±0.2 | 3.9±0.4 | 148±1 | 4.2±0.1 | 66±2 | 5420±100 |

| RECOVERY | 1.0±0.1 | 4.7±0.5 | 148±1 | 4.1±0.1 | 66±3 | 5334±112 |

| ALDO-HT | 0 | 70.0±6.4* | 151±1* | 2.3±0.1* | 81±4* | 5845±288* |

| ALDO-HT+BA | 0 | 72.6±4.8* | 151±1* | 2.2±0.1* | 78±4* | 5940±347* |

| ALDO-HT RECOVERY | 0 | 75.2±7.4* | 151±1* | 2.2±0.1* | 80±4* | 5591±229* |

Values are mean±SE: n=9. PRA indicates plasma renin activity; PALDO plasma aldosterone concentration; PNa, plasma sodium concentration; PK, plasma potassium concentration; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; Na iothal space, sodium iothalamate space.

P<0.05 vs control.

Novelty and Significance.

What’s New?

-Recent technology for chronic electrical activation of the carotid baroreflex and renal nerve ablation are under investigation for the treatment of resistant hypertension, which is often associated with aldosterone excess.

-Thus, this study determined the blood pressure lowering effects of baroreflex activation and surgical renal denervation in dogs with aldosterone-induced hypertension.

What is Relevant?

-Chronic baroreflex activation and renal nerve ablation reduce arterial pressure in some but not in all patients with resistant hypertension. However, little is known about the conditions and types of hypertension that are most responsive to the antihypertensive effects of these medical devices.

Summary

-Baroreflex-mediated reductions in arterial pressure are diminished, but not abolished, after several days of BA when aldosterone contributes to the hypertension.

-In contrast to global suppression of sympathetic activity by BA, renal specific sympathoinhibition is completely devoid of antihypertensive effects when aldosterone is a major determinant of the hypertension.

-These findings suggest that primary aldosteronism may be one type of secondary hypertension that portends diminished blood pressure lowering to device-based therapy in resistant hypertension.

Acknowledgements

We thank David S. Goldstein and Patti Sullivan (NIH/NINDS) for plasma and renal tissue NE determinations. We also thank Willis K. Samson (Saint Louis University) for measuring plasma levels of AVP.

Sources of Funding

This study was funded by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-51971

Footnotes

Disclosures

Thomas E. Lohmeier Consultant fees

Eric D. Irwin Consultant fees

Adam W Cates Employee, CVRx, Inc

Dimitrios Georgakopoulos Employee, CVRx, Inc

References

- 1.Bisognano JD, Bakris G, Nadim MK, Sanchez L, Kroon AA, Schafer J, de Leeuw PW, Sica DA. Baroreflex activation therapy lowers blood pressure in patients with resistant hypertension: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled Rheos Pivotal trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:765–773. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakris GL, Nadim MK, Haller H, Lovett EG, Schafer JE, Bisognano JD. Baroreflex activation therapy provides durable benefit in patients with resistant hypertension: results of long-term follow-up in the Rheos Pivotal Trial. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2012;6:152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoppe UC, Brandt M-C, Wachter R, Beige J, Rump LC, Kroon AA, Cates AW, Lovett EG, Haller H. Minimally invasive system for baroreflex activation therapy chronically lowers blood pressure with pacemaker-like safety profile: results from the Barostim neo trial. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2012;6:270–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Symplicity HTN-1 Investigators. Catheter-based renal sympathetic denervation for resistant hypertension. Durability of blood pressure reduction out to 24 months. Hypertension. 2011;57:911–917. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.163014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esler MD, Böhm M, Sievert H, Rump CL, Schmieder RE, Krum H, Mahfoud F, Schlaich MP. Catheter-based renal denervation for treatment-resistant hypertension: 36 month results from the SYMPLICITY HTN-2 randomized clinical trial. Europ Heart J. 2014;35:1752–1759. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calhoun DA, Jones D, Textor S, Goff DC, Murphy TP, Toto RD, White A, Cushman WC, White W, Sica A, Ferdinand K, Giles TD, Falkner B, Carey RM. Resistant hypertension: diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Professional Education Committee of the Council for High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation. 2008;117:e510–e526. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.189141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark D, III, Ahmed MI, Calhoun DA. Resistant hypertension and aldosterone: an update. Can J Cardiol. 2012;28:318–325. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaddam KK, Nishizaka MK, Pratt-Ubunama MN, Pimenta E, Aban I, Oparil S, Calhoun DA. Characteristics of resistant hypertension. Association between resistant hypertension, aldosterone, and persistent intravascular volume expansion. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1159–1164. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.11.1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaddam K, Corros C, Pimenta E, Ahmed M, Denney T, Aba I, Inusah S, Gupta H, Lloyd SG, Oparil S, Hussain A, Dell`Italia LJ, Calhoun DA. Rapid reversal of left ventricular hypertrophy and intracardiac volume overload in patients with resistant hypertension and hyperaldosteronism. A prospective study. Hypertension. 2010;55:1137–1142. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.141531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Persu A, Jin Y, Baelen M, Vink E, Verloop WL, Schmidt B, Blicher MK, Severino F, Wuerzner G, Taylor A, Perchère-Bertschi A, Jokhaji F, Fadl Elmula FE, Rosa J, Czarnecka D, Ehret G, Kahan T, Renkin J, Widimský J, Jr, Jacobs L, Spiering W, Burnier M, Mark PB, Menne J, Olsen MH, Blankestijn PJ, Kjeldsen S, Bots Ml, Staessen JA. Eligibility for renal denervation. Experience at 11 European Expert Centers. Hypertension. 2014;63:1319–1325. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chapman N, Dobson J, Wilson S, Dahlöf B, Sever PS, Wedel H, Poulter NR. Effect of spironolactone on blood pressure in subjects with resistant hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;49:839–845. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000259805.18468.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Souza F, Muxfeldt E, Fiszman R, Salles G. Efficacy of spironolactone therapy in patients with true resistant hypertension. Hypertension. 2010;55:147–152. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.140988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Václaviík J, Sedlák R, Plachý M, Navrátil K, Plásek J, Jarkovský J, Václavík T, Husár R, Kociánová E, Táborský M. Addition of spironolactone in patients with resistant arterial hypertension (ASPIRANT). A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Hypertension. 2011;57:1069–1075. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.169961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosa J, Widimský P, Toušek P, Petrák O, Čurila K, Waldauf P, Bednář F, Zelinka T, Holaj R, Štrauch B, Šomlóová Z, Táborský M, Václavík J, Kociánová E, Branny M, Nykl I, Jiravský O, Widimský J., Jr Randomized comparison of renal denervation versus intensified pharmacotherapy including spironolactone in true-resistant hypertension. Six month results from the Prague-15 study. Hypertension. 2015;65:407–413. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Persell SD. Prevalence of resistant hypertension in the United States, 2003–2008. Hypertension. 2011;57:1076–1080. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.170308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grassi G, Seravalle G, Brambilla G, Pini C, Alimento M, Facchetti R, Spaziani D, Cuspidi C, Mancia G. Marked sympathetic activation and baroreflex dysfunction in true resistant hypertension. Int J Cardiol. 2014:1020–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.09.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lohmeier TE, Iliescu R, Liu B, Henegar JR, Maric-Bilkan C, Irwin ED. Systemic and renal-specific sympathoinhibition in obesity hypertension. Hypertension. 2012;59:331–338. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.185074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyajima E, Yamada Y, Yoshida Y, Matsukawa T, Shionoiri H, Tochikubo O, Ishii M. Muscle sympathetic nerve activity in renovascular hypertension and primary aldosteronism. Hypertension. 1991;17:1057–1062. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.17.6.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sosa Leon LA, Mckinley MJ, McAllen RM, May CN. Aldosterone acts on the kidney, not the brain, to cause mineralocorticoid hypertension in sheep. J Hypertens. 2002;20:1203–1208. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200206000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsukawa T, Miyamoto T. Does infusion of ANG II increase muscle sympathetic nerve activity in patients with primary aldosteronism? Am J Physiol Regulatory Integrative Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R1873–R1879. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00471.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geerling JC, Loewy AD. Aldosterone and the brain. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;297:F559–F576. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90399.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kontak AC, Wang Z, Arbique D, Adams-Huet B, Auchus RJ, Nesbitt SD, Victor RG, Vongpatanasin W. Reversible sympathetic overactivity in hypertensive patients with primary aldosteronism. J Clin Endocrin Metab. 2010;95:4756–4761. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lohmeier TE, Hildebrandt DA, Dwyer TM, Barrett AM, Irwin ED, Rossing MA, Kieval RS. Renal denervation does not abolish sustained baroreflex-mediated reductions in arterial pressure. Hypertension. 2007;49:373–379. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000253507.56499.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thrasher TN, Keil LC. Systolic pressure predicts plasma vasopressin responses to hemorrhage and vena cava constriction in dogs. Am J Physiol Regulatory Integrative Comp Physiol. 2000;279:R1035–R1042. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.3.R1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stocker SD, Stricker EM, Sved AF. Arterial baroreceptors mediate the inhibitory effect of acute increases in arterial blood pressure on thirst. Am J Physiol Regulatory Integrative Comp Physiol. 2002;282:R1718–R1729. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00651.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lohmeier TE, Dwyer TM, Hildebrandt DA, Irwin ED, Rossing MA, Sedar DJ, Kieval RS. Influence of prolonged baroreflex activation on arterial pressure in angiotensin hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;46:1194–1200. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000187011.44201.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lohmeier TE, Irwin ED, Rossing MA, Sedar DJ, Kieval RS. Prolonged activation of the baroreflex produces sustained hypotension. Hypertension. 2004;43:306–311. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000111837.73693.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lohmeier TE, Iliescu R, Dwyer TM, Irwin ED, Cates AW, Rossing MA. Sustained suppression of sympathetic activity and arterial pressure during chronic activation of the carotid baroreflex. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H402–H409. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00372.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall JE, Guyton AC, Farr BM. A single injection method for measuring glomerular filtration rate. Am J Physiol Regulatory Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol. 1977;232:F72–F76. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1977.232.1.F72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lohmeier TE, Kastner PR, Smith MJ, Jr, Guyton AC. Is aldosteronism important in the maintenance of arterial blood pressure and electrolyte balance during sodium depletion? Hypertension. 1980;2:497–505. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.2.4.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leenen FHH. Actions of circulating angiotensin II and aldosterone in the brain contributing to hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27:1024–1032. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpu066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kandikar SS, Fink GD. Mild DOCA-salt hypertension: sympathetic system and role of renal nerves. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H1781–H1787. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00972.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bravo EL, Tarazi RC, Dustan HP. Multifactorial analysis of chronic hypertension induced by electrolyte-active steroids in trained, unanesthesized dogs. Circ Res. 1977;40:I-140–I-145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pirpiris M, Cox H, Esler M, Jennings GL, Whitworth JA. Mineralocorticoid induced hypertension and norepinephrine spillover in man. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1994;16:147–161. doi: 10.3109/10641969409067946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bravo EL, Tarazi RC, Dustan HP, Fouad FM. The sympathetic nervous system and hypertension in primary aldosteronism. Hypertension. 1985;7:90–96. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.7.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lohmeier TE, Iliescu R. Lowering of blood pressure by chronic suppression of central sympathetic outflow. J Appl Physiol. 2012;113:1652–1658. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00552.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iliescu R, Lohmeier TE. Lowering of blood pressure during chronic suppression of central sympathetic outflow: insight from computer simulations. Clin Exptl Pharmacol Physiol. 2010;37:e24–e33. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2009.05291.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bauersachs J, Jaisser F, Toto R. Mineralocorticoid receptor activation and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist treatment in cardiac and renal diseases. Hypertension. 2015;65:257–263. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kandzari DE, Bhatt DL, Brar S, Devireddy CM, Esler M, Fahy M, Flack JM, Katzen BT, Lea J, Lee DP, Leon MB, Ma A, Massaro J, Mauri L, Oparil S, O’Neill WW, Patel MR, Rocha-Singh K, Sobotka PA, Svetkey L, Townsend RR, Bakris GL. Predictors of blood pressure response in the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial. Eur Heart J. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu441. Nov 16. Pii: ehu441, PMID 25400162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muxfeldt E, de Souza F, Margallo VS, Salles GF. Cardiovascular and renal complications with resistant hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2014;16:471–477. doi: 10.1007/s11906-014-0471-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.