We developed a prognostic score, based on routine parameters easily accessible in daily care. In our analysis of 2269 patients hormone receptor status, the site of metastasis, and metastatic free interval were identified as independent significant prognostic factors for overall survival. Simple clinical measures such as our model may be helpful to further individualize optimal breast cancer care.

Keywords: metastatic breast cancer, prognostic factors, survival

Abstract

Background

The prognosis of metastatic breast cancer (MBC) is extremely heterogeneous. Although patients with MBC will uniformly die to their disease, survival may range from a few months to several years. This underscores the importance of defining prognostic factors to develop risk-adopted treatment strategies. Our aim has been to use simple measures to judge a patient's prognosis when metastatic disease is diagnosed.

Patients and methods

We retrospectively analyzed 2269 patients from four clinical cancer registries. The prognostic score was calculated from the regression coefficients found in the Cox regression analysis. Based on the score, patients were classified into high-, intermediate-, and low-risk groups. Bootstrapping and time-dependent receiver operating characteristic curves were used for internal validation. Two independent datasets were used for external validation.

Results

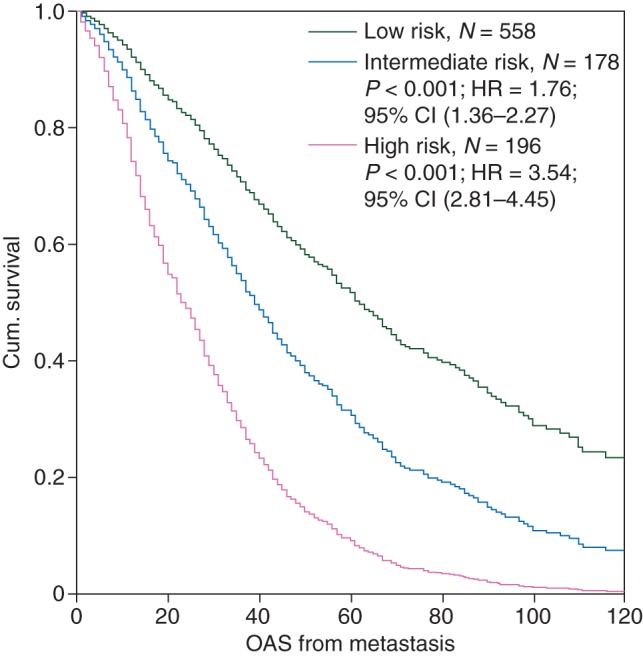

Metastatic-free interval, localization of metastases, and hormone receptor status were identified as significant prognostic factors in the multivariate analysis. The three prognostic groups showed highly significant differences regarding overall survival from the time of metastasis [intermediate compared with low risk: hazard ratio (HR) 1.76, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.36–2.27, P < 0.001; high compared with low risk: HR 3.54, 95% CI 2.81–4.45, P < 0.001). The median overall survival in these three groups were 61, 38, and 22 months, respectively. The external validation showed congruent results.

Conclusions

We developed a prognostic score, based on routine parameters easily accessible in daily clinical care. Although major progress has been made, the optimal therapeutic management of the individual patient is still unknown. Besides elaborative molecular classification of tumors, simple clinical measures such as our model may be helpful to further individualize optimal breast cancer care.

introduction

The clinical behavior of metastatic breast cancer (MBC) is more or less unpredictable reflecting the biologic heterogeneity of this disease. While patients with MBC treated with standard therapy will uniformly die to their disease, survival may range from a few months with a very aggressive course of the disease to several years without major limitations in the quality of life. This underscores the importance of defining prognostic factors to develop risk-adopted treatment strategies.

Prognostic factors might not only help to select the optimal treatment of the individual patient and to develop risk-adjusted treatment strategies. In addition, they could help to better compare patient populations among different trials, or serve as stratification factors in randomized trials to better control potential prognostic imbalances in patient cohorts [1]. An usage example of our score is the comparison of survival times of MBC over the last decades (Ufen et al. submitted).

Clinical and pathological parameters as well as molecular markers might serve as outcome parameters. Up to now, clinical and pathological prognostic factors have been used more often because of their wider availability, while sophisticated technologies are not yet used routinely on a large scale [2].

The stimulus behind this paper was a heuristic prognostic score defined by Possinger et al. [3]. This clinical score is characterized by metastatic pattern, receptor status, and disease-free survival. These are prognostic factors that also appear in other studies [4–15]. Our aim was to calculate a prognostic score for patients with MBC and to validate it both internally and externally. The corresponding factors of the score should be easily available in the clinical routine to judge a patient's prognosis at the onset of metastatic disease.

patients and methods

Data were collected from four different cancer registries. The registries are based on clinical data from individual patients with MBC treated in the Departments of Oncology and Hematology of the University Hospitals Charite-Berlin and Munich-Grosshadern, the University Clinic for Oncology and Haematology at the Klinikum Oldenburg, and the Division of Oncology at the Department of Internal Medicine in Graz between 1980 and 2009. All the patients with MBC treated at the four departments during the registration period were included into the analysis. For the calculation of the prognostic score and its internal validation, the datasets from Munich (n = 403) and Berlin (n = 531) were combined. For external validation of the model, the datasets from Graz (n = 634) and Oldenburg (n = 701) were separately used. We did not exclude patients with initially synchronous metastatic breast carcinoma, which were present in 8.6% (n = 113) in the low-risk group, in 15.7% (n = 72) in the intermediate-risk group, and in 15.4% (n = 76) in the high-risk group.

In each case, the initial site of relapse could be established. Patients underwent routine diagnostic procedures with clinical, radiological, and laboratory work up as far as necessary. Bone marrow biopsies did not belong to the routine procedure, but was undertaken in case of otherwise unexplained blood disorders.

All categorical data were described using numbers and percentages. Quantitative data were presented using median and range or mean and standard deviations. Survival distributions and median survival times were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier product-limit method and were compared using the generalized Wilcoxon test, including the number of patients, the number of events, median survival, and 95% confidence interval (CI). When no information was available, the status was coded as missing data. Statistical comparisons were carried out using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test for categorical data and the log-rank test for censored data. For comparison of the distribution of the score values, we used the independent samples Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

To identify discrete covariates that were univariately significant for survival, we applied log-rank tests and plotted the corresponding Kaplan–Meier curves.

Univariate associations between continuous variables and survival were evaluated by Cox regression analyses. All variables associated with P < 0.10 on univariate analysis were included in the model. The univariate results were omitted here in order not to lengthen the paper, since there was no significant difference to other publications [4–15]. We used the backward selection method, as it leads to fewer errors in estimating the predictors or in selecting the most relevant predictors. Cox regression analyses can be calculated by different statistical methods. It has been shown that the approximation introduced by Efron provides better results than Breslow's approximation. Therefore, we used Efron's approximation. Proportional hazards were tested for all entered variables using statistical and graphical methods (Schoenfeld residuals and log–log plot of cumulative hazard). CIs for the regression coefficients were based on the Wald statistics.

We used hierarchical models to check whether interactions of multivariately significant variables could improve the model.

Overall survival from the time of metastasis was defined as the interval between the first distant metastasis and death. If the patient was lost to follow-up, data were censored at the date of the last known contact. P-values of <0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Internal validity was checked by bootstrapping as this makes efficient use of all the data. Time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves using the Kaplan–Meier (KM) method (based on Bayes' theorem and the Kaplan–Meier survival function) and the Nearest Neighbor Estimation (NNE) [16] were constructed to get additional numerical measures of the accuracy of the score over time. In general, the KM estimator in contrast to NNE does not meet the necessary condition that sensitivity and specificity should be monotone in the continuous variable (here, the score). The new prognostic score and the cut-off points evaluated in the training sample were then separately applied to two-independent validation samples of 634 and 701 patients. To investigate whether a certain risk group of the validation sample would generate a survival curve that would be distinguishable in a statistically significant way from the survival curves of all differing risk groups of the learning sample, we carried out pairwise log-rank tests comparing each risk group of the validation sample with each differing risk group of the learning sample.

Statistical analyses were two-sided and carried out using SPSS 20 and NCSS 2007 for Windows.

results

The derivation cohort consisted of 934 patients with a median age of 56 (range 23–87) years, and the two validation cohorts consisted of 701 and 634 patients with a median age of 57 (range 24–93) and 60 (range 25–88) years, respectively. The median follow-up after recurrence with MBC was 23 months for the derivation cohort and 24 respectively 18 months for the validation cohorts. The baseline characteristics of the derivation cohort are summarized in Table 1 and of the validation cohorts in comparison with the derivation cohort in supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics: derivation cohort

| Score |

Sig | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N = 934, n (%) | Low risk N = 559, n (%) | Intermediate risk N = 179, n (%) | High risk N = 196, n (%) | ||

| Age | |||||

| <50 years | 311 (33.3) | 159 (28.4) | 60 (33.5) | 92 (46.9) | <0.001 |

| 50–69 years | 493(52.8) | 321 (57.4) | 92 (51.4) | 80 (40.8) | |

| ≥70 years | 130 (13.9) | 79 (14.1) | 27 (15.1) | 24 (12.2) | |

| T | |||||

| Unknown | 156 (16.7) | 106 (19.0) | 22 (12.3) | 28 (14.3) | 0.266 |

| 0 | 3 (0.3) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 1 | 256 (27.4) | 150 (26.8) | 51 (28.5) | 55 (28.1) | |

| 2 | 334 (35.8) | 201 (36.0) | 65 (36.3) | 68 (34.7) | |

| 3 | 89 (9.5) | 53 (9.5) | 14 (7.8) | 22 (11.2) | |

| 4 | 96 (10.3) | 47 (8.4) | 26 (14.5) | 23 (11.7) | |

| N | |||||

| Unknown | 153 (16.4) | 103 (18.4) | 32 (17.9) | 18 (9.2) | 0.005 |

| Negative | 266 (28.5) | 168 (30.1) | 49 (27.4) | 49 (25.0) | |

| Positive | 515 (55.1) | 288 (51.5) | 98 (54.7) | 129 (65.8) | |

| M | |||||

| M0 | 781 (83.6) | 496 (88.7) | 134 (74.9) | 151 (77.0) | <0.001 |

| M1 | 153 (16.4) | 63 (11.3) | 45 (25.1) | 45 (23.0) | |

| Grading | |||||

| Unknown | 510 (54.6) | 333 (59.6) | 85 (47.5) | 92 (46.9) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 27 (2.9) | 13 (2.3) | 10 (5.6) | 4 (2.0) | |

| 2 | 198 (21.2) | 113 (20.2) | 46 (25.7) | 39 (19.9) | |

| 3 | 199 (21.3) | 100 (17.9) | 38 (21.2) | 61 (31.1) | |

| Hormonal receptor status | |||||

| Unknown | 273 (29.2) | 216 (38.6) | 39 (21.8) | 18 (9.2) | <0.001 |

| Negative | 160 (17.1) | 0 (0.0) | 29 (16.2) | 131 (66.8) | |

| Positive | 501 (53.6) | 343 (61.4) | 111 (62.0) | 47 (24.0) | |

| Lung metastases | |||||

| No | 722 (77.3) | 476 (85.2) | 138 (77.1) | 108 (55.1) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 212 (22.7) | 83 (14.8) | 41 (22.9) | 88 (44.9) | |

| Liver metastases | |||||

| No | 714 (76.4) | 519 (92.8) | 84 (46.9) | 111 (56.6) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 220 (23.6) | 40 (7.2) | 95 (53.1) | 85 (43.4) | |

| Effusion metastases | |||||

| No | 838 (89.7) | 515 (92.1) | 161 (89.9) | 162 (82.7) | 0.001 |

| Yes | 96 (10.3) | 44 (7.9) | 18 (10.1) | 34 (17.3) | |

| Brain metastases | |||||

| No | 916 (98.1) | 557 (99.6) | 173 (96.6) | 186 (94.9) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 18 (1.9) | 2 (0.4) | 6 (3.4) | 10 (5.1) | |

| Bone metastases | |||||

| No | 495 (53.0) | 273 (48.9) | 111 (62.0) | 111 (56.6) | 0.021 |

| Yes | 439 (47.0) | 286 (51.2) | 68 (38.0) | 85 (43.4) | |

| Bone marrow metastases | |||||

| No | 914 (97.9) | 559 (100.0) | 173 (96.6) | 182 (92.9) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 20 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (3.4) | 14 (7.1) | |

| Soft tissue metastases | |||||

| No | 594 (63.6) | 391 (69.9) | 114 (63.7) | 89 (45.4) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 340 (36.4) | 168 (30.1) | 65 (36.3) | 107 (54.6) | |

| MFI | Mean 49 ± 55 median 31 0–454 |

Mean 62 ± 60 median 47 0–454 |

Mean 34 ± 43 median 22 0–312 |

Mean 26 ± 35 median 14 0–240 |

<0.001 |

| MFI, months | |||||

| MFI ≤ 24 | 406 (43.5) | 166 (29.7) | 100 (55.9) | 140 (71.4) | <0.001 |

| MFI > 24 | 528 (56.5) | 393 (70.3) | 79 (44.1) | 56 (28.6) | |

MFI: metastasis-free interval.

prognostic factors and association with outcome

In the Cox regression model, hormone receptor (HR) status, the specific site of metastasis, and metastatic-free interval (MFI) were significantly associated with survival from first relapse (Table 2). Table 2 contains the regression coefficients, the standard errors, P-values, hazard ratios, and 95% CIs for hazard ratios. The regression coefficients—multiplied by 10 and rounded—were then transformed into the prognostic score (Table 3). The derived prognostic score discriminates three groups, which have low-, intermediate-, or high risks (Table 3).

Table 2.

Cox regression model

| Variables in the equation |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | Wald | df | Significance | Exp(B) | 95% CI for Exp(B) |

||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| MFI | 0.340 | 0.102 | 11.181 | 1 | 0.001 | 1.405 | 1.151 | 1.714 |

| HR | 0.788 | 0.129 | 37.193 | 1 | 0.000 | 2.198 | 1.707 | 2.832 |

| Liver | 0.686 | 0.122 | 31.627 | 1 | 0.000 | 1.985 | 1.563 | 2.521 |

| Effusion | 0.411 | 0.161 | 6.516 | 1 | 0.011 | 1.509 | 1.100 | 2.069 |

| Brain | 0.850 | 0.288 | 8.709 | 1 | 0.003 | 2.339 | 1.330 | 4.112 |

| Bone | 0.388 | 0.108 | 12.960 | 1 | 0.000 | 1.474 | 1.193 | 1.821 |

| Bone marrow | 1.022 | 0.296 | 11.950 | 1 | 0.001 | 2.770 | 1.557 | 4.961 |

| Soft tissue | 0.415 | 0.110 | 14.236 | 1 | 0.000 | 1.515 | 1.221 | 1.879 |

| Lung | 0.346 | 0.118 | 8.524 | 1 | 0.004 | 1.413 | 1.120 | 1.782 |

MFI: metastasis-free interval; HR: hormone receptor; B: regression coefficient; SE: standard error; Wald: test statistic; df: degrees of freedom; Exp(B): hazard ratio.

Table 3.

Calculation of the score and cut-off points of the prognostic groups

| Parameter | Value | Points |

|---|---|---|

| Calculation | ||

| MFI | ≤2 years | 3 |

| HR | Negative | 8 |

| Liver | Yes | 7 |

| Effusion | Yes | 4 |

| Brain | Yes | 8 |

| Bone | Yes | 4 |

| Bone marrow | Yes | 10 |

| Soft tissue | Yes | 4 |

| Lung | Yes | 4 |

| For all other values: | 0 | |

| Points | Prognosis | 5-year survival |

| Prognostic groups | ||

| ≤8 | Low risk | 51% |

| 9–14 | Intermediate risk | 31% |

| ≥15 | High risk | 12% |

MFI: metastasis-free interval; HR: hormone receptor.

overall survival according to the prognostic score

The three prognostic groups showed highly significant differences regarding overall survival from the time of metastasis (intermediate compared with low risk: HR 1.76, 95% CI 1.36–2.27, P < 0.001; high compared with low risk: HR 3.54, 95% CI 2.81–4.45, P < 0.001) (Figure 1). The median overall survival in these three groups were 61, 38, and 22 months, respectively.

Figure 1.

Overall survival from metastasis of the three prognostic groups in the derivation cohort.

The hazard ratios for premenopausal patients with respect to the three prognostic groups are: intermediate compared with low risk: HR 1.75, 95% CI 1.20–2.56, P = 0.004; high compared with low risk: HR 3.13, 95% CI 2.29–4.28, P < 0.001). The hazard ratios for postmenopausal patients with respect to the three prognostic groups are: intermediate compared with low risk: HR 1.76, 95% CI 1.24–2.50, P = 0.001; high compared with low risk: HR 4.16, 95% CI 2.94–5.87, P < 0.001).

internal validation

For the internal validation of our prognostic score, we used bootstrapping and time-dependent ROC curves. Bootstrapping showed a very high consistency of the results (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). The time-dependent ROC curves showed that the prognostic score is a good marker to predict up to 3-year overall survival for patients with MBC (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

external validation

For the external validation of our results, we used two different datasets including 634 respectively 701 patients from two different institutions (supplementary Figure S2a and b, available at Annals of Oncology online). The distributions of the score values are significantly different in the derivation cohort and the two validation cohorts (independent samples Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, P < 0.001), with patients having higher score values in the Oldenburg and Graz cohorts. However, there were no significant (P = 0.067) differences between the distribution of the risk groups (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

There are also significant differences in median survival times. The Berlin/Munich dataset showed longer median survival times than the other two cohorts [Berlin/Munich: 46 months, 95% CI (41.0–51.0); Oldenburg: 26 months, 95% CI (23.3–28.8); Graz: 22 months, 95% CI (19.6–24.4)]. Nevertheless, the score discriminated the three prognostic groups significantly in all datasets and showed similar results regardless of the origin of the patient data (supplementary Figure S2a and b, available at Annals of Oncology online).

discussion

In our analysis of 2269 patients, HR status, the specific site of metastasis, and MFI were identified as independent significant prognostic factors for overall survival calculated from the onset of metastasis.

HR status has long been known as a very important prognostic and predictive factor in breast cancer, as it is correlated to malignant behavior. In the relatively new era of molecular classification, this importance has even been reinforced [17].

Tumors predominantly metastasizing to the bone behave clinically different from those metastasizing to the liver, lung, or brain [18, 19]. The different subtypes of primary breast cancer do not only differ in their risk of developing a relapse at all, but also in the pattern of the relapse, i.e. local versus distant and different metastatic sites. This has been shown for the classical immunohistochemical variations according to HR status and HER2 status [20–22] and recently, also for the molecular subtypes [23]. Therefore, it is not surprising that the site of metastasis influences the prognosis.

Metastatic sites, however, might also have a predictive value [11, 24, 25]. For example, higher response rates of taxanes were shown in patients with visceral metastasis compared with those with non-visceral metastasis [24].

A short MFI, usually defined as <12 or <24 months, is a negative prognostic factor for overall survival in advanced breast cancer [6, 26]. It has, therefore, been proposed as a surrogate parameter in well-known clinical practice guidelines to judge a patient's need for a more aggressive therapeutic strategy [27, 28].

Prognostic factors in the setting of metastatic disease have been identified before. For example, an analysis of 1038 patients from a single institution in France has shown hormonal receptor status, site of metastasis, adjuvant chemotherapy, age at diagnosis of primary breast cancer, size of primary tumor, and grading of primary tumor as significant prognostic factors [5]. The single most significant independent factor was the site of metastasis.

A recent Spanish analysis including well over 2000 patients with recurrent breast cancer was used to calculate a prognostic score in an attempt similar to our study [7]. According to a multivariate analysis, the following parameters influenced overall survival significantly: age at initial diagnosis, stage at initial diagnosis, grading, hormonal receptor status, nodal ratio, administration of neo-/or adjuvant chemotherapy, dominant site of metastasis, number of hormonal lines in metastatic disease, and response to first-line therapy. This approach differs to ours as it includes variables unknown at the time of the diagnosis of metastasis, such as the number of lines of hormonal therapies for metastatic disease and response to first-line therapy. Nevertheless, a score was developed that could discriminate patients into three prognostic groups with a significantly different median overall survival of 3.69, 2.27, and 1.02 years, comparable with our results of 5.1, 3.2, and 1.8 years.

Similar results were also found in a Greek cohort analysis, in which performance status, HR status, previous adjuvant chemotherapy, previous adjuvant hormonal treatment, visceral metastasis at entry, and number of metastatic sites were found to be prognostic parameters [8]. Older analyses found similar results with HR, nodal status, disease-free interval, and site of initial recurrence as significant prognostic factors for survival after recurrence [9, 10, 12].

Besides subtle differences between the significance of prognostic factors, the location of metastasis and HR status are consistent findings in all mentioned publications. Our score depends on only three factors (HR status, sites of metastasis, and MFI) that are easily available in the daily clinical routine.

The major drawback of our analysis is the fact that HER2/neu, an accepted prognostic factor, is not included in the model. The measurement of HER2 became a routine after the year 2000, and too few data are available in our databases to be included into our model.

In conclusion, we can offer a simple prognostic model to determine a patient's prognosis when metastatic disease is diagnosed. Although our score has been validated internally and externally by two independent cohorts of patients, it needs to be re-evaluated once new therapeutic options become available that may potentially influence our model. Further studies may be necessary in order to determine whether the risk groups may benefit differentially from more intensive treatment options. Besides elaborative molecular classification of tumors, simple clinical measures such as our model may be helpful to further individualize the care of patients with MBC.

disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

references

- 1.Byar DP. Identification of prognostic factors. In: Buyse ME, Staquet MJ, Sylvester RS, editors. Cancer Clinical Trials. Methods and Practice. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1984. pp. 423–443. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Espinosa E, Zamora P, Fresno JA, et al. High-throughput techniques in breast cancer: has their time come? Med Hypotheses Res. 2006;3:761–768. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Possinger K, Wagner H, Langecker P, et al. Treatment toxicity reduction: breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 1987;14:263–274. doi: 10.1016/0305-7372(87)90017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hortobagyi GN, Smith TL, Legha SS, et al. Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1983;1:776–786. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1983.1.12.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Largillier R, Ferrero JM, Doyen J, et al. Prognostic factors in 1,038 women with metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:2012–2019. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kramer JA, Curran D, Piccart M, et al. Identification and interpretation of clinical and quality of life prognostic factors for survival and response to treatment in first-line chemotherapy in advanced breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:1498–1506. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Puente J, Lopez-Tarruella S, Ruiz A, et al. Practical prognostic index for patients with metastatic recurrent breast cancer: retrospective analysis of 2,322 patients from the GEICAM Spanish El Alamo Register. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;122:591–600. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0687-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dafni U, Grimani I, Xyrafas A, et al. Fifteen-year trends in metastatic breast cancer survival in Greece. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;119:621–631. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0630-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark GM, Sledge GW, Jr, Osborne CK, et al. Survival from first recurrence: relative importance of prognostic factors in 1,015 breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5:55–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1987.5.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Insa A, Lluch A, Prosper F, et al. Prognostic factors predicting survival from first recurrence in patients with metastatic breast cancer: analysis of 439 patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999;56:67–78. doi: 10.1023/a:1006285726561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurebayashi J, Sonoo H, Inaji H, et al. Endocrine therapies for patients with recurrent breast cancer: predictive factors for responses to first- and second-line endocrine therapies. Oncology. 2000;59(Suppl 1)):31–37. doi: 10.1159/000055285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koenders PG, Beex LV, Kloppenborg PW, et al. Human breast cancer: survival from first metastasis. Breast Cancer Study Group. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1992;21:173–180. doi: 10.1007/BF01975000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andreopoulou E, Hortobagyi GN. Prognostic factors in metastatic breast cancer: successes and challenges toward individualized therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3660–3662. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vogel CL, Azevedo S, Hilsenbeck S, et al. Survival after first recurrence of breast cancer. The Miami experience. Cancer. 1992;70:129–135. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920701)70:1<129::aid-cncr2820700122>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang J, Clark GM, Allred DC, et al. Survival of patients with metastatic breast carcinoma: importance of prognostic markers of the primary tumor. Cancer. 2003;97:545–553. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heagerty PJ, Lumley T, Pepe MS. Time-dependent ROC curves for censored survival data and a diagnostic marker. Biometrics. 2000;56:337–344. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parker JS, Mullins M, Cheang MC, et al. Supervised risk predictor of breast cancer based on intrinsic subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1160–1167. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minn AJ, Gupta GP, Siegel PM, et al. Genes that mediate breast cancer metastasis to lung. Nature. 2005;436:518–524. doi: 10.1038/nature03799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrell JC, Prat A, Parker JS, et al. Genomic analysis identifies unique signatures predictive of brain, lung, and liver relapse. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132:523–535. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1619-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maki DD, Grossman RI. Patterns of disease spread in metastatic breast carcinoma: influence of estrogen and progesterone receptor status. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:1064–1066. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slimane K, Andre F, Delaloge S, et al. Risk factors for brain relapse in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1640–1644. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dawood S, Broglio K, Esteva FJ, et al. Defining prognosis for women with breast cancer and CNS metastases by HER2 status. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1242–1248. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kennecke H, Yerushalmi R, Woods R, et al. Metastatic behavior of breast cancer subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3271–3277. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo X, Loibl S, Untch M, et al. Re-challenging taxanes in recurrent breast cancer in patients treated with (neo-) adjuvant taxane-based therapy. Breast Care. 2011;6:279–283. doi: 10.1159/000330946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmid P, Possinger K, Bohm R, et al. Body mass index as predictive parameter for response and time to progression (TTP) in advanced breast cancer patients treated with letrozole or megestrol acetate. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2000;19:103a. (abstr 398) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang E, Buchholz TA, Meric F, et al. Classifying local disease recurrences after breast conservation therapy based on location and histology: new primary tumors have more favorable outcomes than true local disease recurrences. Cancer. 2002;95:2059–2067. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kreienberg R, Kopp I, Albert U. Interdisziplinäre S3-Leitlinie für die Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge des Mammakarzinoms. 2008. http://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/032-045OL_l_S3__Brustkrebs_Mammakarzinom_Diagnostik_Therapie_Nachsorge_2012-07.pdf .

- 28.Network. NCC. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Breast Cancer [Internet]. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp .

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.