36 % and 34 % of all soft tissue sarcoma patients who received pazopanib in the EORTC phase II and III studies had a long PFS and / or OS respectively. 3.5 % of patients remained progression free under pazopanib for more than two years. Good performance status, low / intermediate grade of the primary tumour and a normal hemoglobin level at baseline were advantageous for long-term outcome.

Keywords: EORTC, long-term responders, long-term survivors, pazopanib, soft tissue sarcoma, STBSG

Abstract

Background

Pazopanib recently received approval for the treatment of certain soft tissue sarcoma (STS) subtypes. We conducted a retrospective analysis on pooled data from two EORTC trials on pazopanib in STS in order to characterize long-term responders and survivors.

Patients and methods

Selected patients were treated with pazopanib in phase II (n = 118) and phase III study (PALETTE) (n = 226). Combined median progression-free survival (PFS) was 4.4 months; the median overall survival (OS) was 11.7 months. Thirty-six percent of patients had a PFS ≥ 6 months and were defined as long-term responders; 34% of patients survived ≥18 months, defined as long-term survivors. Patient characteristics were studied for their association with long-term outcomes.

Results

The median follow-up was 2.3 years. Patient characteristics were compared among four subgroups based on short-/long-term PFS and OS, respectively. Seventy-six patients (22.1%) were both long-term responders and long-term survivors. The analysis confirmed the importance of known prognostic factors in metastatic STS patients treated with systemic treatment, such as performance status and tumor grading, and additionally hemoglobin at baseline as new prognostic factor. We identified 12 patients (3.5%) remaining on pazopanib for more than 2 years: nine aged younger than 50 years, nine females, four with smooth muscle tumors and nine with low or intermediate grade tumors at initial diagnosis. The median time on pazopanib in these patients was 2.4 years with the longest duration of 3.7 years.

Conclusions

Thirty-six percent and 34% of all STS patients who received pazopanib in these studies had a long PFS and/or OS, respectively. For more than 2 years, 3.5% of patients remained progression free under pazopanib. Good performance status, low/intermediate grade of the primary tumor and a normal hemoglobin level at baseline were advantageous for long-term outcome.

NCT00297258 (phase II) and NCT00753688 (phase III, PALETTE).

introduction

Soft tissue sarcomas (STS) are a heterogeneous group of tumors arising mainly from the embryonic mesoderm and can be localized anywhere in the body. STS comprise more than 50 different histological tumor entities that exhibit great differences in terms of clinical behavior, pathogenesis and genetic alterations. They are relatively rare with ∼10 000 cases diagnosed each year in the United States. More than 40% are diagnosed in patients older than 55 years, although all age groups are affected. If diagnosed at an early stage and complete surgical removal of all tumor manifestations can be achieved, the prognosis is favorable. However, in up to 50% of patients, distant metastases will occur [1]. The median OS for advanced patients is ∼12 months and has remained substantially unchanged during the last 20 years. Long-term survival occurs only in a small percentage of metastatic patients [2] clearly underpinning the need for new therapeutic strategies.

One of these approaches is to target angiogenesis which is one of the crucial drivers for the growth and dissemination of malignancies. Pazopanib is an orally available angiogenesis inhibitor that targets vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR)-1, -2 and -3 and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)-α and -β and c-kit [3]. Phase I studies defined the recommended single-agent dose as 800 mg once daily [4]. In 2009, pazopanib was approved in the United States for the treatment of advanced and metastatic renal cell carcinoma [5]. The EORTC Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group (STBSG) carried out a phase II study (EORTC 62043) [6] and a phase III study (EORTC 62072, PALETTE) [7] evaluating the activity of pazopanib in STS patients in collaboration with GSK. A total of 142 patients were recruited in the phase II trial into four different strata: adipocytic STS, leiomyosarcomas, synovial sarcomas and other STS types. The adipocytic sarcoma stratum was closed due to insufficient activity. For the other three strata, the primary end point (PFR12weeks) [8] was met. In the subsequent PALETTE trial, 369 patients progressive on prior lines of standard chemotherapy (for advanced metastatic disease) were randomly assigned to receive either pazopanib (n = 246) or placebo (n = 123). The study demonstrated a significant advantage in PFS of 3 months in favor of the pazopanib arm [4.6 versus 1.6 months; hazard ratio (HR) = 0.31, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.24–0.40, P < 0.0001] [7]. These results led to approval of the drug for STS. The median PFS for patients treated with pazopanib in the PALETTE trial was 4.6 months, and the median OS was 12.5 months, respectively. Interestingly, a considerable number of patients showed a significantly longer PFS and OS. In this paper, we aimed to analyze the long-term pazopanib responders and survivors and focus on the characteristics and possible prognostic factors in this cohort of patients.

patients and methods

analysis population

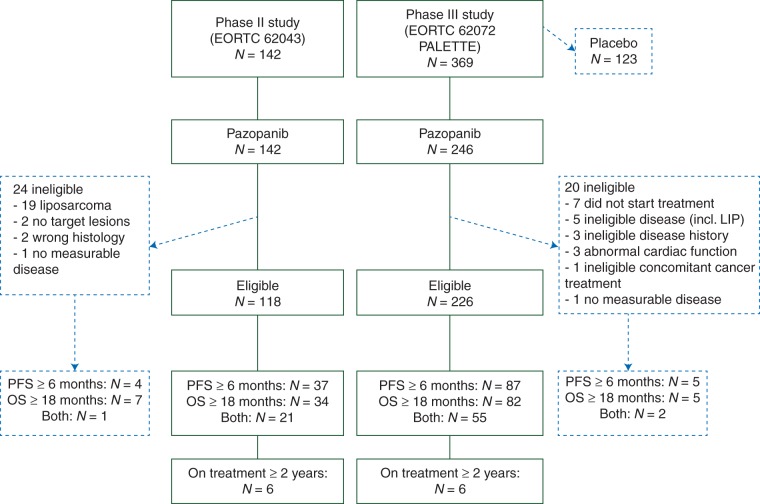

Patients considered for this retrospective analysis (n = 388) were assigned to treatment with pazopanib 800 mg daily in the phase II study 62043 (n = 142) [6] and the phase III study 62072 (PALETTE) (n = 246) [7]. Key characteristics of the two trials are shown in supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online. Exclusion of patients with adipocytic sarcomas—who were not part of the phase III trial anyway—and ineligible patients due to other reasons (n = 44; Figure 1) resulted in a selected population of 344 patients. The following patient characteristics were studied for their association with outcome: gender, age, performance status, tumor localization, histology by central review, grade of the primary tumor at initial diagnosis, baseline hematology results, treatment exposure, adverse events and post protocol therapy. In addition, we studied the characteristics of a subgroup of ‘very long-term’ responders and survivors, defined by a clinical benefit with PFS and OS beyond 2 years. The clinical cut-off dates for the data were 15 October 2009 for the 62043 study and 24 October 2011 for the 62072 study.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram.

statistical analysis

PFS was defined as from the date of registration/randomization to the first documentation of disease progression or death, whichever occurred first. Patients were censored at the date of last patient visit if no progression or death was observed. OS was defined as from the date of registration/randomization to the date of death. Patients alive at the time of the clinical cut-off were censored at the date of last follow-up. Long-term responders and survivors were identified as the 30–35% of patients with the longest duration of response or stable disease (per RECIST v1.0) and survival, respectively. Time-to-event end points were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier techniques. Patient characteristics were compared among four subgroups based on short-/long-term PFS and OS, respectively, using descriptive tables. A logistic multivariable regression analysis was used to assess the value of the prognostic factors to identify the subgroup of patients of long-term responders or survivors. Two approaches were considered: (i) without adjusting for censoring before the time point of interest and (ii) adjusting for censoring by using the pseudo-value regression technique proposed by Andersen et al. [9] and Klein et al. [10]. Furthermore, a multivariable Cox regression analysis was done to assess the prognostic value of a selection of baseline characteristics, information relating to treatment received and early objective response to treatment on PFS and OS. For this purpose, a landmark analysis approach was used with the cut-off chosen at 3 months, because this was the first scheduled assessment in the phase II trial and a timing at which a tumor response evaluation was scheduled in both studies. First the univariate contribution of each of the prognostic factors was investigated. Those factors with a P-value ≤0.20 were included in a multivariate model, which was then further reduced using backward selection until only factors with a P-value of ≤0.05 remained. In the second part of the analysis, the characteristics of patients remaining on treatment with pazopanib for more than 2 years were tabulated.

results

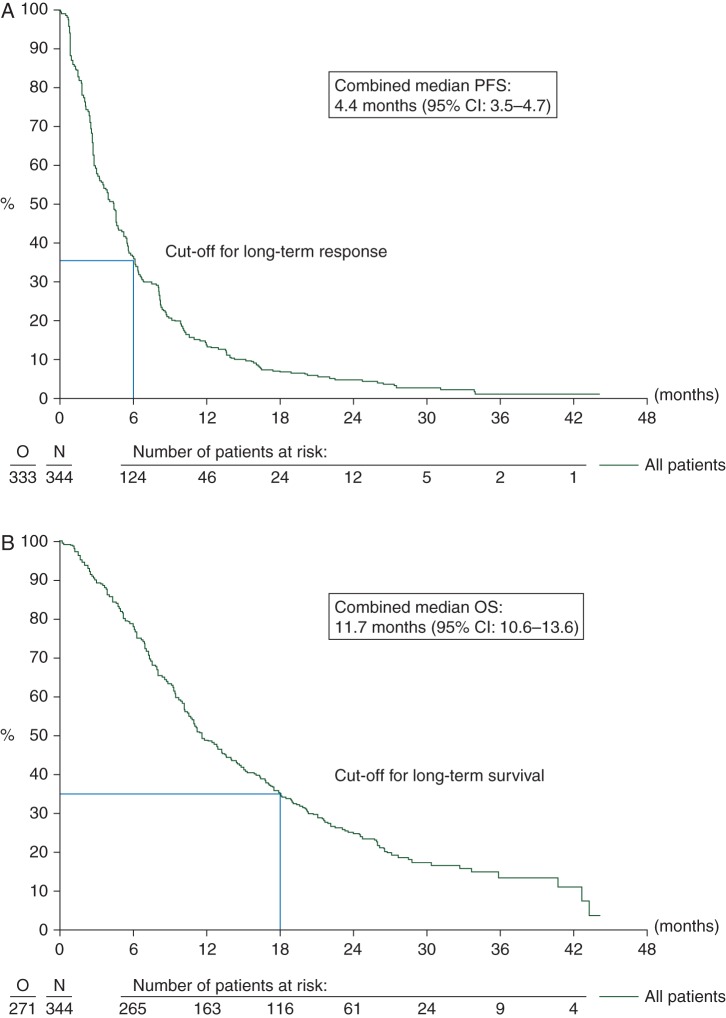

The clinical cut-off dates for this analysis resulted in a pooled database with a median follow-up of 2.3 years (IQR 1.9–2.9). Progression or death was observed in 333 patients (116 from the 62043 study and 217 from the 62072 study) resulting in a combined median PFS of 4.4 months (95% CI: 3.5–4.7) (Figure 2A). PFS rate at 6 months is estimated at 36.5% (95% CI: 31.4–41.6); 124 patients (36%), of whom 37 were recruited in the phase II study and 87 in the phase III study had a PFS ≥ 6 months and were defined as long-term responders (CR, PR and SD). Seventy-three patients (21.2%) were still alive at the last documented follow-up (16 in the 62043 study and 57 in the 62072 study); the combined OS was 11.7 months (95% CI: 10.6–13.6) (Figure 2B). The main cause of death was progression of disease (249, 91.9%) followed by toxicity (8, 2.9%). OS at 18 months is estimated at 35.3% (95% CI: 30.2–40.4); 116 patients (34%), of whom 34 from the phase II study and 82 from the phase III study had an OS ≥ 18 months and were defined as long-term survivors. Seventy-six patients (22.1%) were both long-term responders and long-term survivors.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves showing the combined (A) median progression-free (PFS) and (B) median overall survival (OS) for patients being treated with pazopanib.

The patient characteristics were compared among the four subgroups as defined above based on short-/long-term PFS and OS, respectively (Table 1). The median age at the start of the studies was lowest (51 years) in the subgroup of patients who were both long-term responders and survivors, with 35.5% younger than 40 years. In both patient groups with long-term OS, there were more females than males (60% in the PFS < 6 months and 68.4% in the PFS ≥ 6 months group, respectively), whereas in the categories with OS < 18 months, the distribution between males and females was more balanced. There were also more patients with performance status 0 in the two groups with OS ≥ 18 months (72.5% in the PFS < 6 months and 61.8% in the PFS ≥ 6 months group, respectively) than in both corresponding groups with OS < 18 months (43.3% and 35.4%, respectively). There was no histological subtype associated with better or worse outcome, but the number of certain subtypes was too low in this analysis to draw any conclusion. Patients with a high grade tumor (201, 58.4%) tend to have shorter PFS and/or survival. On the other hand, 55.3% of the long-term responders and survivors had a low or intermediate grade tumor at the time of initial diagnosis. Regarding involved primary tumor sites, there does not seem to be a clear trend toward sites associated with better or worse outcome. In the category with long-term PFS and OS, 76.3% of patients had stable disease as best response and 23.7% of patients achieved a partial response. Progressive disease was the most common reason to discontinue treatment. More patients in the short-term PFS group (<6 months) discontinued treatment due to toxicity of pazopanib (40.3%) compared with the long-term PFS group (10.9%).

Table 1.

Patients' characteristics

| Response categories |

Total (n = 344) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFS < 6 months and OS < 18 months (n = 180) | PFS < 6 months and OS ≥ 18 months (n = 40) | PFS ≥ 6 months and OS < 18 months (n = 48) | PFS ≥ 6 months and OS ≥ 18 months (n = 76) | ||

| Age (years) | |||||

| Median | 54 | 57 | 55 | 51 | 54 |

| Q1–Q3 | 42–65 | 46–64 | 45–64 | 34–62 | 41–64 |

| Gender [n (%)] | |||||

| Male | 83 (46.1) | 16 (40.0) | 25 (52.1) | 24 (31.6) | 148 (43.0) |

| Female | 97 (53.9) | 24 (60.0) | 23 (47.9) | 52 (68.4) | 196 (57.0) |

| Performance status | |||||

| 0 | 78 (43.3) | 29 (72.5) | 17 (35.4) | 47 (61.8) | 171 (49.7) |

| 1 | 102 (56.7) | 11 (27.5) | 31 (64.6) | 29 (38.2) | 173 (50.3) |

| Site of primary | |||||

| Extremities | 63 (35.0) | 14 (35) | 19 (39.6) | 27 (35.5) | 123 (35.8) |

| Retro-/intra-abdominal | 35 (19.4) | 8 (20.0) | 6 (12.5) | 16 (21.1) | 65 (18.9) |

| Visceral | 38 (21.7) | 12 (30.0) | 8 (15.8) | 16 (21.1) | 74 (21.5) |

| Other | 44 (24.4) | 6 (15.0) | 15 (33.3) | 17 (22.4) | 82 (23.8) |

| Histology (central review) | |||||

| Leiomyosarcoma | 60 (33.3) | 27 (67.5) | 17 (35.4) | 33 (43.4) | 137 (39.8) |

| Synovial sarcoma | 39 (21.7) | 4 (10.0) | 13 (27.1) | 12 (15.8) | 68 (19.8) |

| Other | 81 (45.0) | 9 (22.5) | 18 (37.5) | 31 (40.8) | 139 (40.4) |

| Tumor grade (central review) | |||||

| Low | 10 (5.6) | 2 (5.0) | 3 (6.3) | 13 (17.1) | 28 (8.1) |

| Intermediate | 55 (30.6) | 14 (35.0) | 15 (31.3) | 29 (38.2) | 113 (32.8) |

| High | 114 (63.3) | 24 (60.0) | 29 (60.4) | 34 (44.7) | 201 (58.4) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.6) |

| Best overall response | |||||

| Partial response | 7 (3.9) | 3 (7.5) | 9 (18.8) | 18 (23.7) | 37 (10.8) |

| Stable disease | 78 (43.3) | 24 (60.0) | 37 (77.1) | 58 (76.3) | 197 (57.3) |

| Progressive diseasea | 95 (52.8) | 13 (32.5) | 2 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 110 (32.0) |

| Baseline lymphocyte countb | |||||

| Grade 0 | 115 (63.9) | 28 (70.0) | 25 (52.1) | 54 (71.1) | 222 (64.5) |

| Grade 1 | 33 (18.3) | 9 (22.5) | 10 (20.8) | 12 (15.8) | 64 (18.6) |

| Grade ≥ 2 | 32 (17.2) | 3 (7.5) | 13 (27.1) | 10 (13.2) | 57 (16.5) |

| Baseline hemoglobinb | |||||

| Grade 0 | 68 (37.8) | 23 (57.5) | 18 (37.5) | 49 (64.5) | 158 (45.9) |

| Grade ≥ 1 | 111 (61.7) | 17 (42.5) | 30 (62.5) | 27 (35.5) | 185 (53.8) |

aIncluding patients dying before first response assessment (early death) and non-evaluable best response.

bNote that for one patient from the phase II study, no baseline hematology data were available.

From a multivariate logistic regression analysis for long-term response (PFS ≥ 6 months, yes or no), the presence of bone metastases [P = 0.029; odds ratio (OR) = 0.44, 95% CI: 0.21–0.92] and a low baseline hemoglobin ≥ grade 1 (P = 0.032; OR = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.36–0.96) were identified to be significant negative factors (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). This result was confirmed in the analysis adjusting for censoring before 6 months (available from authors). Bone metastases were found in 15.1% (52/344) of all selected patients and in 9 out of the 76 (12%) patients with both long-term PFS and OS. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis for long-term survival (OS ≥ 18 months, yes or no), performance status 0 (P = 0.002; OR = 2.21, 95% CI: 1.33–3.66) was found to increase the likelihood of surviving 18 months or more (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). Patients with low baseline hemoglobin levels (when compared with normal baseline hemoglobin, P = 0.001; OR = 0.43, 95% CI: 0.26–0.71) are less likely to survive 18 months. In the analysis adjusting for censoring before 18 months (available from authors), both factors could be verified, additionally, tumor grade at initial diagnosis turned out to be a prognostic factor (P = 0.025; OR = 0.31, 95% CI: 0.12–0.81). Interestingly, tumor grade is significant only for OS, not for PFS. Results of the multivariate Cox regression model with a landmark for PFS at 3 months are provided as supplementary Material, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Interestingly, we identified 12 patients (3.5%) remaining on pazopanib therapy for more than 2 years. The median age of these patients was 42 years with nine of them younger than 50 years. Further characteristics are depicted in supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online. Notably, all 12 patients presented with lung metastases. Two of these patients achieved a partial response; the remaining 10 patients experienced stable disease as best overall response. The median time on pazopanib treatment was 2.4 years with the longest duration of 3.7+ years. Seven patients stopped treatment due to disease progression; one patient stopped pazopanib due to toxicity (pulmonary embolism) possibly related to the study drug. The median dose intensity was estimated as 591 mg/day (ranging between 287 and 790 mg/day). This cohort of patients experienced only few grade 3 or more adverse events while on treatment. At the time of data acquisition, four patients were still progression free and only one patient had died before the end of the study. The median PFS duration of these patients was 2.3 years (ranging between 1.7 and 3.7 years); the median OS was 2.8 years (ranging between 2.1 and 3.7 years).

discussion

Standard systemic chemotherapy including agents such as doxorubicin and ifosfamide still forms the backbone of palliative treatment in advanced STS. More recently, newer compounds have been added to the treatment armamentarium of STS, such as gemcitabine (plus or minus docetaxel) and trabectedine [11]. Other compounds such as eribulin [12] are under investigation.

Pazopanib is the first anti-angiogenic drug marketing approved for STS. In the phase III trial, the objective response rate was 6% for pazopanib versus 0% for placebo (67% stable diseases in the pazopanib arm versus 38% in the placebo arm, respectively) [7]. The increase in PFS in the pazopanib arm was statistically significant with a median of 3 months prolongation (P < 0.0001). Interestingly, in some patients, long-term response and survival have been observed representing the main topic of this paper.

Pooling data from two EORTC trials investigating patients treated orally with pazopanib (n = 344), we could demonstrate that 36% (n = 124) and 34% (n = 116) of STS patients had a PFS ≥ 6 months and were defined as long-term responders, or demonstrated an OS ≥ 18 months defined as long-term survivors, respectively. Seventy-six patients (22.1%) were both long-term responders and survivors. The descriptive as well as the multivariate analysis confirmed the importance of prognostic factors such as performance status and tumor grade. A normal hemoglobin level at baseline was also found to be of prognostic relevance for PFS and OS. This is well documented for other solid tumors [13, 14], but not for STS [15]. Several analyses from the STBSG addressed the question of prognostic outcome to anthracycline- and ifosfamide-containing first-line treatments in STS [2, 16, 17]. Interestingly, characteristics associated with long-term outcome for pazopanib-treated patients are similar to those associated with long-term outcome to other agents applied in STS such as performance status and grade of the primary tumor. One additional characteristic translating into long-term response or survival could be identified in this analysis: hemoglobin level at baseline. Lymphopenia has been demonstrated as an independent prognostic factor for survival in several cancers including advanced STS [18]; however, it was not in our analysis.

We also considered an analysis on the placebo-treated patients in the phase III PALETTE trial (n = 123), however, we refrained from doing that for several reasons: (i) The question of the present study is not to look at prognostic factors in metastatic STS patients, but the aim was to get a better insight into the characteristics of long-term responders and survivors on pazopanib. (ii) Patients were treated with placebo only in the phase III study, which may introduce bias when comparing these results with those from the pazopanib-treated patients pooled from both the phase II and III trials. (iii) Most importantly, there were too few patients in the placebo group satisfying the criteria for the long-term outcomes (6 patients with PFS ≥ 6 months and 37 patients with OS ≥ 18 months) and therefore, no meaningful data on the placebo-treated patients could be provided for this analysis. Without analyses of a control group, no conclusions can be drawn regarding the interaction between treatment with pazopanib and the identified prognostic factors.

Twelve patients (3.5%) demonstrated a clinical benefit even beyond 2 years with a median time on pazopanib treatment of 2.4 years and the longest duration of 3.7 years. As expected, these patients were mainly young, female, with a good performance status and had more low or intermediate grade tumors at the time of initial diagnosis and all of them had pulmonary metastases.

Due to the limited number of patients, no conclusive statements could be drawn regarding histologies. We could not clearly identify a histological subtype more frequently represented in the cohort of 76 patients with both long-term PFS and OS. Interestingly, besides a large number of leiomyosarcomas (n = 31) and synovial sarcomas (n = 10), this category contained four of the nine patients with vascular tumors (hemangioendothelioma, no angiosarcomas), four of seven patients with alveolar soft part sarcomas, four out of seven patients with solitary fibrous tumors and two out of six patients with desmoplastic small round cell tumors. However, the number of certain subtypes was too low in this analysis to draw any statistical conclusion. In the 12 ‘super long-term’ responders, similar histological subtypes could be found responding well to pazopanib (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Limitations of the analysis carried out are the differences in patient populations and disease characteristics (e.g. prior treatment, histological subtypes) of the two trials. The different study designs and end points of the phase II and III studies have to be taken into account when interpreting the results. Furthermore, the different follow-up schedules can also be a potential source of bias when combining the PFS data from the two studies.

Clearly, more research is needed to reveal factors associated with long-term outcome. Other potential factors to be of scientific interest regarding long-term outcome include angiogenesis-related soluble factors in serum [19], genetic markers or molecular characteristics. Finally, to get a better insight into the subgroup of patients benefiting from pazopanib over a long period of time, it would need a much larger group of patients than entered in these EORTC studies. This is especially of relevance when studying the relation between different histological subgroups and patients' outcome. It would require continuous international collaboration to get this insight fast.

disclosure

BK: honoraria from GSK; SS: honoraria and research funding from GSK; RH: shares in GSK; SB: honoraria from GSK; WG: honoraria and research funding from GSK. All remaining authors have declared no conflict of interest.

funding

This study was supported by the EORTC Charitable Trust.

Supplementary Material

references

- 1.Kasper B, Hohenberger P. Pazopanib: a promising new agent in the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas. Future Oncol. 2011;7:1373–1383. doi: 10.2217/fon.11.116. doi:10.2217/fon.11.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blay JY, van Glabbeke M, Verweij J, et al. Advanced soft-tissue sarcoma: a disease that is potentially curable for a subset of patients treated with chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:64–69. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00480-x. doi:10.1016/S0959-8049(02)00480-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris PA, Boloor A, Cheung M, et al. Discovery of 5-[[4-[(2,3-Dimethyl-2H-indazol-6-yl)methylamino]-2 pyrimidinyl]amino] 2 methylbenzenesulfonamide (pazopanib), a novel and potent vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor. J Med Chem. 2008;51:4632–4640. doi: 10.1021/jm800566m. doi:10.1021/jm800566m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hurwitz HI, Dowlati A, Saini S, et al. Phase I trial of pazopanib (GW786034), an oral multikinase angiogenesis inhibitor, in patients with advanced cancer: results of safety, pharmacokinetics, and clinical activity. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4220–4227. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2740. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keisner SV, Shah SR. Pazopanib—the newest tyrosine kinase inhibitor for the treatment of advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Drugs. 2011;71:443–454. doi: 10.2165/11588960-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sleijfer S, Ray-Coquard I, Papai Z, et al. Pazopanib, a multikinase angiogenesis inhibitor, in patients with relapsed or refractory advanced soft tissue sarcoma: a phase II study from the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group (EORTC Study 62043) J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3126–3132. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.3223. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.21.3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van der Graaf WTA, Blay JY, Chawla SP, et al. Pazopanib for metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (PALETTE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1879–1886. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60651-5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60651-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Glabbeke M, Verweij J, Judson J, et al. Progression-free rate as the principal end point for phase II trials in soft tissue sarcomas. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:543–549. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00398-7. doi:10.1016/S0959-8049(01)00398-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersen PK, Klein JP, Rosthoj S. Generalized linear models for correlated pseudo-observations with applications to multi-state models. Biometrika. 2003;90:15–27. doi:10.1093/biomet/90.1.15. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein JP, Logan B, Harhoff M, et al. Analyzing survival curves at a fixed point in time. Stat Med. 2007;26:4505–4519. doi: 10.1002/sim.2864. doi:10.1002/sim.2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Cesne A, Blay JY, Judson I, et al. Phase II study of ET-743 in advanced soft tissue sarcomas: a European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) soft tissue and bone sarcoma group trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:576–584. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.180. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.01.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schöffski P, Ray-Coquard IL, Cioffi A, et al. Activity of eribulin mesylate in patients with soft-tissue sarcoma: a phase 2 study in four independent histological subtypes. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:1045–1052. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70230-3. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70230-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olmos D, Ang JE, Gomez-Roca C, et al. Pitfalls and limitations of a single-centre, retrospectively derived prognostic score for phase I oncology trial participants—reply to Fussenich et al.: a new, simple and objective prognostic score for phase I cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:594–596. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.11.004. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoff CM. Importance of hemoglobin concentration and its modification for the outcome of head and neck cancer patients treated with radiotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2012;51:419–432. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2011.653438. doi:10.3109/0284186X.2011.653438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stefanovski PD, Bidoli E, De Paoli A, et al. Prognostic factors in soft tissue sarcomas: a study of 395 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2002;28:153–164. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2001.1242. doi:10.1053/ejso.2001.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sleijfer S, Ouali M, van Glabbeke M, et al. Prognostic and predictive factors for outcome to first-line ifosfamide-containing chemotherapy for adult patients with advanced soft tissue sarcomas: an exploratory, retrospective analysis on large series from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group (EORTC-STBSG) Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:72–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.09.022. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2009.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.V Glabbeke M, van Oosterom AT, Oosterhuis JW, et al. Prognostic factors for the outcome of chemotherapy in advanced soft tissue sarcoma: an analysis of 2.185 patients treated with anthracycline-containing first-line regimens—a European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:150–157. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ray-Coquard I, Cropet C, Van Glabbeke M, et al. Lymphopenia as a prognostic factors for overall survival in advanced carcinomas, sarcomas, and lymphomas. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5383–5391. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3845. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sleijfer S, Gorlia T, Lamers C, et al. Cytokine and angiogenic factors associated with efficacy and toxicity of pazopanib in advanced soft-tissue sarcoma: an EORTC-STBSG study. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:639–645. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.328. doi:10.1038/bjc.2012.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.