Abstract

Background

Perianal Paget’s disease (intraepithelial adenocarcinoma) is rare, and sometimes difficult to diagnose because symptoms are nonspecific. It is often non-invasive but frequently recurs locally. Invasive disease can metastasize to distant sites.

Objective

Review diagnosis, management, outcomes of patients with perianal Paget’s disease.

Design

Institutional databases were queried for all cases of perianal Paget’s disease at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center 1950-2011. Clinicopathologic factors were investigated for association with recurrence and survival.

Setting

Tertiary care center.

Patients

65 patients with perianal Paget’s disease: 35(54%) female; median age at diagnosis 66(60–72 years);41 had invasive disease/24 non-invasive; 56% with invasive disease were male.

Main Outcome Measures

Median follow-up; disease status; local and distant recurrence; distant recurrence; sites of recurrence; disease-specific survival; overall survival; treatment modality.

Results

95% with invasive, 87% with non-invasive disease were symptomatic at presentation; the most common symptoms were pruritus and perianal bleeding. Duration of symptoms was longer in patients with invasive(12 months, 4-18 months) versus non-invasive (3.5 months, 1-10 months)(p = 0.02)) disease. Synchronous malignancies unrelated to the primary were noted in 5 with invasive/3 with non-invasive disease. Non-invasive disease was treated with wide local excision; invasive disease with wide local excision(32 (78%)) or abdominoperineal resection(9 (22%)). Forty-one patients(27 invasive/14 non-invasive) required multiple operations for tumor clearance. In those with invasive disease, median time to recurrence was 5 years, median tumor-specific survival 10 years.

Limitations

Retrospective study, limited by selection bias.

Conclusions

Perianal Paget’s disease is associated with nonspecific symptoms, frequently delaying diagnosis. Wide local excision is the treatment of choice if negative margins can be obtained. Abdominoperineal resection should be considered for invasive disease. Local recurrence is common; follow-up includes periodic proctoscopy and digital exam. Invasive disease can metastasize to distant sites; follow-up should include examination of inguinal lymph nodes and imaging of liver and lungs.

Keywords: Perianal Paget’s disease, Anal neoplasia, Wide local excision, Abdominoperineal resection

INTRODUCTION

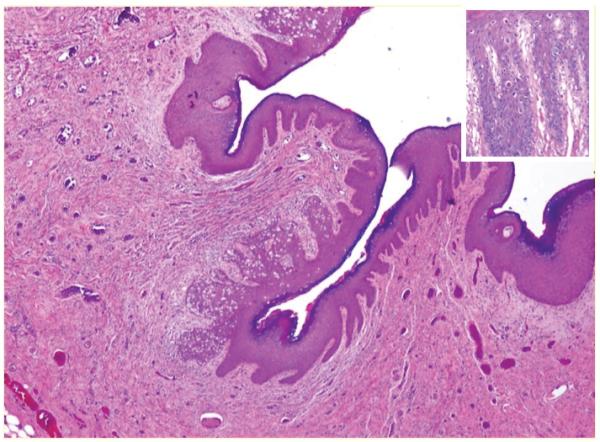

More than a century ago, in a report on breast cancer patients, Sir James Paget published pathologic findings involving the areolar tissue of the nipple that was subsequently named after him. Since this initial discovery, Paget’s disease has been reported in several extramammary sites, including the perineum, vulva, scrotum, groin, axilla and thigh.1 Paget’s cells represent an intraepithelial adenocarcinoma. Their origin has been a subject of debate in the past; however, the distribution of lesions in regions with increased density of apocrine glands suggests that these glands may be the site of origin.2, 3 Paget’s is easily distinguished from Bowen’s disease if signet ring cells with vacuolated, pale cytoplasm are present; these are usually positive, with a periodic acid-Schiff mucin stain.2, 4 (Figure 1) The association between Paget’s disease and other carcinomas arising in remote regions of the gastrointestinal tract, genitourinary tract, and remote areas of skin, has been noted in previous publications.5, 6 The relatively rare nature of this disease, however, has made it difficult to develop treatment recommendations. The aim of this study was to review our institution’s 60-year experience with this rare disease.

Figure 1.

A photomicrograph of H&E appearance of anal Paget’s disease showing pale stained Paget’s cells within squamous epithelium (Inset shows that the Paget’s cells are large and contain abundant mucin-filled cytoplasm)

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The Pathology Department and Colorectal Surgery Service databases at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center were queried for all cases of perianal Paget’s disease seen between 1950 and 2011. The data were collected and stored in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations, and a waiver of authorization was obtained from the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Institutional Review Board to allow analysis of patient information. Cases reported in a previous publication from our institution were included in this study, as differences in management and outcome between invasive and non-invasive disease had not been specifically noted.6 Charts were reviewed, and patients with histologic confirmation of Paget’s disease originating in the perianal area were included. All cases of Bowen’s disease were excluded, as was disease originating in the perivulvar area.

All patients were treated with surgical resection. Some required additional surgery to ensure complete tumor clearance. Factors included in the study were: age at diagnosis; gender; operative treatment; use of adjuvant treatment; margins of resection; histopathology, including presence of invasive disease; recurrence; and death. Invasive Paget’s disease was documented when histopathology identified tumor cells in the stroma underlying the squamous mucosa or skin. Locoregional recurrence was defined as biopsy proven tumor recurrence in inguinal lymph nodes. Primary sources included all available medical records, as well as tumor registry and social security death index.

Results were reported as median and corresponding interquartile range (IQR) or 95% confidence interval (95% CI), as appropriate. Recurrence-free survival (RFS), disease-specific survival (DSS) and overall-survival (OS) were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier product-limit method, and the difference was measured by the log-rank test. Continuous variables were compared with the χ2-test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS software version 20.

RESULTS

Patient and tumor characteristics

Sixty-five patients met the inclusion criteria, of whom 35 (54%) were female (Table 1). The median age at the time of diagnosis was 66 years (60–72 years). Invasive Paget’s disease was noted in 41 patients and non-invasive Paget’s in 24. Fifty-six percent of patients with invasive disease were male. Ninety-five percent of patients with invasive disease and 87% of patients with non-invasive disease were symptomatic. The most common symptoms included pruritus and perianal bleeding. The duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis of Paget’s disease was significantly longer in patients with invasive disease (12 months, 4-18 months) compared to those with non-invasive lesions (3.5 months, 1-10 months; (p = 0.02). Synchronous malignancies, unrelated to the primary Paget’s, were noted in 5 patients with invasive and 3 with non-invasive disease. These included bladder cancer (1), thyroid cancer (1), endometrial cancer (1), lymphoma (1), breast cancer (2), and basal cell carcinoma (2).

Table 1. Tumor, Treatment and Outcome Parameters of patients with Perianal Paget’s Disease.

| Invasive Paget’s disease (N = 41) |

Non-invasive Paget’s disease (N = 24) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 54 (59 - 72) | 66 (61 - 73) | ns |

| Gender F/M | 18 / 23 | 17 / 7 | 0.03 |

| Symptoms | |||

| - pruritus | 19 (46) | 18 (75) | 0.02 |

| - bleeding | 11 (27) | 0 | |

| - pain | 5 (12) | 0 | |

| - mass | 4 (10) | 2 (8) | ns |

| - incidental | 2 (5) | 4 (17) | ns |

| Duration of symptoms before diagnosis (months) |

12 (4 - 18) | 4 (1 - 10) | 0.02* |

| Type of surgery | |||

| - APR | 9 (22) | 0 | 0.01 |

| - WLE | 32 (78) | 24 (100) | |

| Plastic surgery reconstruction |

8 (20) | 9 (37) | ns |

| Positive margin after | |||

| - 1st resection§ | 14 (34) | 10 (42) | ns |

| Recurrence+ | 23 (56) | 12 (29) | ns |

| - local | 18(44) | 12 (29) | |

| - locoregional | 8 (20) | 0 | |

| - distant | 3 (7) | 0 | |

| Recurrence-free survival (years) |

5.1 (CI: 2.6 - 7.5) | 6.1 (CI: 1 - 15) | ns |

| Disease-specific survival (years) |

10.9 (CI: 4.5 - 12) | Median not reached | 0.004 |

| Overall-survival (years) |

10.4 (CI: 5.6 - 15) | 16.3 (CI: 12 - 21) | 0.03 |

APR: Abdominoperineal resection, WLE: Wide local excision. Ns: not significant.

All patients with locoregional and/or distant recurrence had recurrent local disease as well. Locoregional recurrence was defined as biopsy proven tumor recurrence in inguinal lymph nodes.

All patients with evidence of persistent disease on pathological examination had negative surgical margins after immediate subsequent resection. Continuous variables are shown as median and corresponding interquartile range. Data is presented with percentages in brackets. Ns: not significant.

Mann-Whitney-U-test.

Management

Patients with a diagnosis of non-invasive Paget’s disease were treated with wide local excision (WLE). Patients diagnosed with invasive disease, either at time of presentation or after initial excision, were treated with WLE or abdominoperineal resection (APR): 32 (78%) WLE; 9 (22%) APR. (Table 1) Forty-one patients—27 with invasive and 14 with non-invasive disease—required multiple operations to ensure complete tumor clearance. Repeat procedures were common in patients with invasive disease. A variety of procedures were utilized to reconstruct the perineum after WLE or APR. These included local rotational flap (6), advancement flap (5), skin graft (3), and myocutaneous flap (3). Reconstruction was performed in 8 patients with invasive disease and 9 with non-invasive disease. Adjuvant 5-fluorouracil based chemoradiation was used in 7 patients, adjuvant radiation in 1.

Outcome

Median follow-up from time of diagnosis was 5.3 years (2.5 – 10.8 years). Disease status at time of last follow-up was: 23 alive with no evidence of disease; 18 alive with recurrent disease; 10 dead of disease; 14 dead of other causes. Of the 41 patients with invasive Paget’s disease, 23 (56%) recurred. Recurrences arose in the following anatomic locations: perianal skin (18); inguinal lymph nodes (8); distant sites (3). Two patients had synchronous local and distant recurrence; 4 had synchronous local and lymphatic recurrence. All patients with locoregional and/or distant recurrence had recurrent local disease as well. Of the 24 patients with non-invasive Paget’s disease, 12 (29%) developed local perianal recurrence. Most common distant sites of disease include liver and lung.

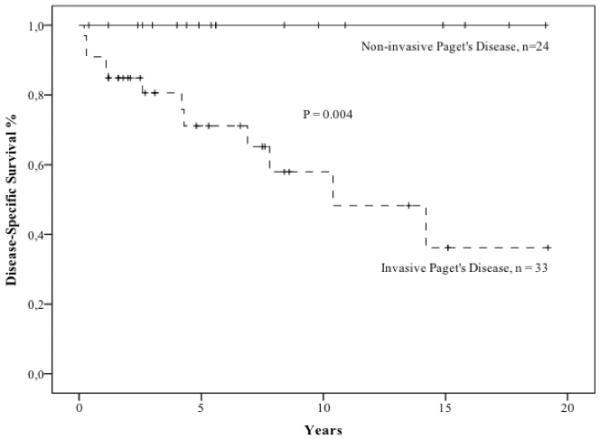

Disease-specific survival (DSS) was significantly shorter in patients with invasive Paget’s disease (10.9 years; 95% CI: 4.5 – 12 years) compared to those with non-invasive disease (median not reached; p = 0.004) (Figure 2). Overall survival (OS) was significantly shorter in patients with invasive disease (median 10.4 years, 95% CI: 5.6 - 15 years) compared to those with non-invasive disease (median 16.3 years, 95% CI: 12 - 21 years; p=0.03) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Disease-specific survival is shown for patients with invasive and non-invasive perianal Paget’s disease

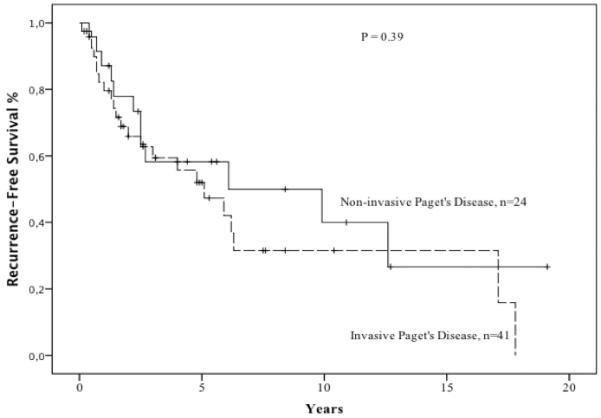

In patients with invasive disease, surgical resection (WLE versus APR) did not impact recurrence or DSS (Table 1, Figure 3). The cohort of patients receiving adjuvant treatment was small; therefore, analysis of its effect was limited.

Figure 3.

Recurrence-free survival is shown for patients with invasive and non-invasive perianal Paget’s disease

DISCUSSION

Perianal Paget’s is a rare disease. Most reported series are small, and biased towards invasive disease. In this series we report on 65 patients with perianal Paget’s disease treated at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center over a 60-year period. Not surprisingly, the vast majority had non-specific perianal symptoms, including pain and pruritus, which can mimic more common, benign anorectal problems such as hemorrhoids, pruritus ani, and fissures. This often leads to a delay in diagnosis.

Delay may also result from difficulty in securing a correct pathological interpretation. Differentiation of Pagetoid cells from those associated with Bowen’s disease or anal melanoma can be difficult for the non-specialized pathologist.7 Furthermore, invasive and non-invasive Paget’s commonly coexist. This makes the identification of invasive disease more challenging. Repeat diagnostic procedures are often required.

Invasive Paget’s disease may be primary or secondary. The cell of origin for primary Paget’s disease has been an issue of debate in the literature. Presumed cells of origin have included pluripotent epidermal stem cells, adnexal stem cells, apocrine glands, and intra-epidermal Toker cells. Secondary Paget’s disease often results from a downward spread of rectal adenocarcinoma2; thus, it is not surprising that a diagnosis of Paget’s is associated with colorectal cancer.8 Distinguishing primary from secondary anal Paget‘s disease is not always clear-cut.

In our series, the high proportion of patients ultimately diagnosed with invasive disease (41/65, 63%) is a result of the institution’s tertiary referral pattern. Invasive disease is usually identified after an attempted local excision for what is thought to be non-invasive disease. Although APR was required only in patients with invasive disease, some with non-invasive disease required significant local excision and perineal reconstruction.

Recurrence remains a common problem, even after apparent complete resection. In our series, half of the patients with invasive perianal Paget’s and one-fourth of those with non-invasive disease recurred, respectively. This is undoubtedly related to the “skip” nature of the disease: discontinuous spread of Pagetoid cells in the epidermis beyond the clinically apparent margin. For this reason, Beck et al. recommend routine perianal biopsies 1 cm from the edge of the visible lesion, in all four quadrants, before resection.9, 10 In this series, we liberally used mapping with 4-mm dermatologic punch biopsies taken at 1 cm intervals beyond the visible margin of the lesion to define the extent of local excision. However, in light of the high local recurrence rate of Paget’s disease noted in this and other studies,11 the value of such extensive mapping procedures is uncertain.

We found that half of the recurrences in this study were delayed, and diagnosed 5 years after the primary resection. While the goal of treating perianal Paget’s disease is to maximize local control, surgical deformity and morbidity should be minimized. Sphincter preservation to optimize quality of life is paramount in patients with non-invasive disease.11 Patients with invasive disease should be considered for more aggressive surgery, including APR if necessary. The role of neoadjuvant radiation to assist in complete resection or to avoid APR may deserve investigation but was not used in our cohort. However, it is important to individualize treatment based on the patient’s desires, functional status and co-morbidities, as well as extent of disease.

In this as in previous studies,6 a proportion of patients with invasive Paget’s succumb to disease. Of 41 patients with invasive Paget’s in the current analysis, 10 (16%) died of disease and 8 (20%) of other causes.

The current study, like all retrospective analyses, is limited by selection bias. This most likely explains why we noted no difference in recurrence-free survival between patients undergoing WLE and APR; patients with extensive, and possibly aggressive, disease were more likely to require APR. Similarly, we are not able to comment on the utility of adjuvant therapy. Patients undergoing adjuvant treatment had worse survival compared to those who did not; however, it may be the case that patients with extensive disease were more likely to be offered adjuvant therapy (radiation or chemoradiation). Similar observations have been reported in the existing literature.12

In conclusion, diagnosing perianal Paget’s disease is difficult, and is generally delayed while other diagnoses are entertained. Perianal Paget’s is often an indolent process with a tendency to recur locally. Wide local excision is the treatment of choice if negative margins can be obtained. APR should be considered for patients with invasive Paget’s who require radical surgery to clear their disease. In patients with invasive disease, the median time to recurrence and median tumor-specific survival are 5 years and 10 years, respectively. While patients with non-invasive disease require periodic proctoscopy and digital exam after treatment (initially biannually and then annually), follow-up of patients with invasive disease should include examination of inguinal lymph nodes and imaging studies of the liver and lungs (usually annually).

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded in part by the cancer center core grant P30 CA008748. The core grant provides funding to institutional cores, such as Biostatistics and Pathology, which were used in this study.

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

Daniel R. Perez, MD: Conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting article and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published.

Atthaphorn Trakarnsanga, MD: Conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting article and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published.

Jinru Shia, MD: Conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting article and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published.

Garrett M. Nash, MD, MPH: Conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting article and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published.

Larissa K. Temple, MD: Conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting article and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published.

Philip B. Paty, MD: Conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting article and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published.

José G. Guillem, MD, MPH: Conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting article and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published.

Julio Garcia-Aguilar, MD, PhD: Conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting article and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published.

Martin R. Weiser, MD: Conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting article and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jones RE, Jr, Austin C, Ackerman AB. Extramammary Paget’s disease. A critical reexamination. Am J Dermatopathol. 1979;1:101–132. doi: 10.1097/00000372-197900120-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armitage NC, Jass JR, Richman PI, Thomson JP, Phillips RK. Paget’s disease of the anus: a clinicopathological study. Br J Surg. 1989;76:60–63. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800760119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzpatrick JE. The histologic diagnosis of intraepithelial Pagetoid neoplasms. Clin Dermatol. 1991;9:255–259. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(91)90015-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arminski TC, Pollard RJ. Paget’s disease of the anus secondary to a malignant papillary adenoma of the rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 1973;16:46–55. doi: 10.1007/BF02589910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quan SH. Anal and para-anal tumors. Surg Clin N Am. 1978;58:591–603. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)41541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarter MD, Quan SH, Busam K, Paty PP, Wong D, Guillem JG. Long-term outcome of perianal Paget’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:612–616. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6618-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reed W, Oppedal BR, Eeg Larsen T. Immunohistology is valuable in distinguishing between Paget’s disease, Bowen’s disease and superficial spreading malignant melanoma. Histopathology. 1990;16:583–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1990.tb01163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helwig EB, Graham JH. Anogenital (extramammary) Paget’s disease. A clinicopathological study. Cancer. 1963;16:387–403. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196303)16:3<387::aid-cncr2820160314>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beck DE, Fazio VW. Premalignant lesions of the anal margin. South Med J. 1989;82:470–474. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198904000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beck DE, Fazio VW. Perianal Paget’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1987;30:263–266. doi: 10.1007/BF02556169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams SL, Rogers LW, Quan SH. Perianal Paget’s disease: report of seven cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1976;19:30–40. doi: 10.1007/BF02590848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thirlby RC, Hammer CJ, Jr., Galagan KA, Travaglini JJ, Picozzi VJ., Jr. Perianal Paget’s disease: successful treatment with combined chemoradiotherapy. Report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:150–152. doi: 10.1007/BF02055547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]