Abstract

Background

Siglec-F is a glycan binding protein selectively expressed on mouse eosinophils. Its engagement induces apoptosis, suggesting a pathway for ameliorating eosinophilia in asthma and other eosinophil-associated diseases. Siglec-F recognizes sialylated, sulfated glycans in glycan binding assays, but the identities of endogenous sialoside ligands and their glycoprotein carriers in vivo are unknown.

Methods

Lungs from normal and mucin-deficient mice, as well as mouse tracheal epithelial cells from mice, were interrogated in vitro and in vivo for the expression of Siglec-F ligands. Western blotting and immunocytochemistry used Siglec-F-Fc as a probe for directed purification, followed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometric analysis of recognized glycoproteins. Purified components were tested in mouse eosinophil binding assays and flow cytometry-based cell death assays.

Results

We detected mouse lung glycoproteins that bound to Siglec-F; binding was sialic-acid dependent. Proteomic analysis of Siglec-F binding material identified Muc5b and Muc4. Cross-affinity enrichment and histochemical analysis of lungs from mucin-deficient mice assigned and validated the identity of Muc5b as one glycoprotein ligand for Siglec-F. Purified mucin preparations carried sialylated and sulfated glycans, bound to eosinophils and induced their death in vitro. Mice conditionally deficient in Muc5b displayed exaggerated eosinophilic inflammation in response to intratracheal installation of IL-13.

Conclusions

These data identify a previously unrecognized endogenous anti-inflammatory property of airway mucins by which their glycans can control lung eosinophilia through engagement of Siglec-F.

Keywords: Eosinophil, asthma, Siglec-F, mucin, Muc5b, Muc4, apoptosis, glycan ligands, epithelium, glands, lung, airway

INTRODUCTION

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by bronchial hyper-reactivity and reversible obstruction of the airway.1 Current asthma therapies, such as corticosteroids, target these inflammatory processes. Antagonists of cytokines (such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 and others) are in various stages of clinical trials.2 These agents either directly or indirectly can reduce eosinophils, a leukocyte linked to asthma pathogenesis and exacerbations in a sizable subset of asthmatic endotypes and phenotypes.3 While many previous studies have focused on identifying pathways that initiate or promote inflammation in asthma, relatively few have targeted mechanisms for resolving the underlying eosinophilia.4 Efforts to selectively target eosinophils, both in animal models and in clinical trials, have yielded promising results in a number of airway inflammatory diseases.5 Therefore, novel therapeutic opportunities may arise from understanding the cellular and molecular processes that limit lung eosinophilia in asthma.

Toward this goal, we have investigated the functions of the Siglec family of innate immune receptors in lung inflammatory diseases. Siglecs (sialic acid-binding, immunoglobulin-like lectins) are cell surface proteins found predominantly on leukocytes.6 Human Siglec-8 is selectively expressed on eosinophils and mast cells, and its closest functional paralog in the mouse is Siglec-F, which is specifically expressed by eosinophils and alveolar macrophages, but is absent from mast cells in the mouse.7, 8 Glycan array screening demonstrated that both Siglec-8 and Siglec-F preferentially bind the sialoside glycans 6’-sulfo-sialyl-Lewis X (6’-S-Sialyl-Lex) and 6’-sulfo-sialyl-N-acetyl-D-lactosamine (6’-S-Sialyl-LacNAc).9 Although human Siglec-8 shows high selectivity for these sulfated and sialylated glycans, mouse Siglec-F is somewhat more promiscuous, recognizing other non-sulfated, multivalent, sialylated LacNAc structures (Fig 1). Engagement of Siglec-8 or Siglec-F with stimulatory antibodies or with synthetic glycan ligands that carry binding epitopes causes eosinophil death in vitro.7 Furthermore, administration of anti-Siglec-F antibodies in mouse models of eosinophilia, allergic asthma, and eosinophilic gastroenteritis normalizes eosinophil numbers and abrogates tissue remodeling.7 Siglec-F deficient mice, as well as mice deficient in a key enzyme required to synthesize its α3-sialylated glycan ligands, namely the α2-3 sialyltransferase ST3Gal-III, display a selective enhancement of allergic eosinophilic inflammation.9-12

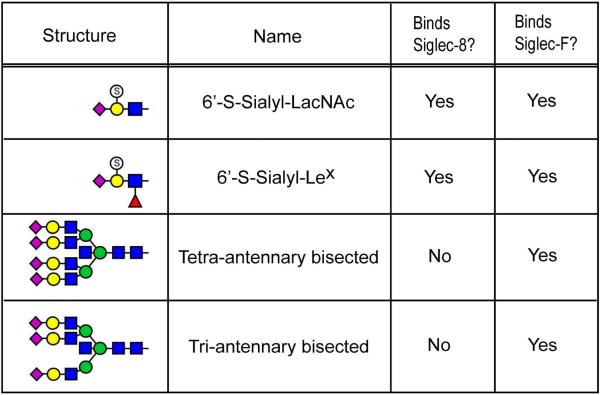

Figure 1. Glycans recognized by Siglec-8 and Siglec-F.

The four most potent glycan structures demonstrated to bind Siglec-F-Fc by glycan microarray analysis are shown. Graphical representations of glycan structures in this and all other figures are in accordance with the guidelines proposed and generally accepted by the glycomics community: blue square, N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc); green circle, mannose (Man); yellow circle, galactose (Gal); red triangle, fucose (Fuc); pink diamond, sialic acid as N-acetylneuraminic acid (NeuAc); light blue diamond, sialic acid as N-glycolylneuraminic acid (NeuGc); S inside open circle, sulfate.

It is well established that glycan sialylation is critical for Siglec-F and Siglec-8 binding, but the importance of sulfation and the identity of the glycoprotein carriers that present glycan ligands in vivo are currently unknown. In fact, recent data indicate that mice lacking either or both of the best candidate sulfotransferase enzymes for production of 6’-S-Sialyl-Lex or 6’-S-Sialyl-LacNAc (namely, chondroitin 6-O-sulfotransferase, C6ST1, and keratin sulfate galactose 6-O-sulfotransferase, KSGal6ST) exhibit no reduction in the expression of Siglec-F ligands in lung and exhibit no change in eosinophilia in response to parasite infestation, bringing into question the importance of endogenous glycan sulfation for Siglec-F engagement.13 Additional studies have demonstrated the existence of inflammation and cytokine-inducible, protease-sensitive, high molecular weight material in the mouse airway that bind Siglec-F in a sialic acid-dependent manner.11-15 By applying a series of cellular, molecular and glycoproteomic approaches, we report the identification of Muc5b as a sialic acid-dependent, lung-derived, death-inducing glycoprotein that binds Siglec-F expressed on eosinophils.

METHODS

Mice

Eight to twelve week-old C57BL/6 wild-type mice, IL-5 transgenic mice (IL-5 tg), and IL-5 transgenic mice x Siglec-F null mice (IL-5 transgenic x Siglec-F−/−) were used in our experiments. IL-5 transgenic x Siglec-F−/− mice were generated by breeding of IL-5 transgenics ((CD3d-IL5)NJ.1638Nal transgenic mice16, kindly provided by Drs. James and Nancy Lee, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ) with Siglec-F−/−mice10 (kindly provided by Dr. Ajit Varki, University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA). Breeding sets of St3gal3−/− mice were kindly provided by Dr. Jamey Marth (University of California, San Diego, CA) as previously described17, but due to breeding limitations, St3gal3+/- heterozygous mice were used in these studies. Tissues from Muc5b null mice18 were used, as well as tissues from Muc5ac null19 x IL-13 transgenic mice20 given doxycycline at 625 ppm in chow (Teklad lab diet, Harlan Laboratories, Denver, CO) ad libitum for 7 days. In addition, to study changes in induced eosinophilic inflammation in Muc5b deficient mice, conditional knockout mice were generated by crossing Muc5blox/lox mice with Tg(SFTPC-Cre) mice.21 Resulting Muc5b / mice had no immunohistochemically detectable Muc5b protein in the lower airways (see Online Repository Figure E1). To detect natural tissue ligands, trachea, frozen lung tissue sections, whole mouse lung extracts and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) samples were harvested. In some experiments, mice were intraperitoneally sensitized with 500 μg ovalbumin (OVA) in 1 mg alum on days 0 and 14, then challenged intranasally with 200 μg OVA on days 17, 19, and 21 to induce eosinophilic airway inflammation as described.9 In addition, Muc5b Δ/Δ and wild-type littermate control mice were treated with either 25 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or 5 μg of IL-13 in 25 μl PBS intratracheally (i.t.) using a Hamilton glass syringe and a gavage needle. To reduce the effects of bacterial infection in Muc5b deficient airways, Muc5b Δ/Δ and wild-type control animals were placed on antibiotic diets 1 week prior to challenge.18 All animal procedures were approved by the Johns Hopkins University and the University of Colorado School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

Cell cultures & whole lung extracts

Primary mouse tracheal epithelial cells (mTEC) were harvested from mouse trachea as previously described.22 Collected non-adherent cells were re-suspended and then incubated in upper chambers of cell culture insert membranes (0.4 μM pore size, Becton-Dickinson Labware, Franklin Lakes, NJ) pre-coated with 50 μg/mL filter-sterilized type I rat tail collagen (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) in 0.02 N acetic acid under submerged conditions. After reaching sufficient levels of transmembrane resistance, media was removed from the upper chamber to establish an air-liquid interface (ALI) for 2 weeks. In some experiments, ALI cells were stimulated with either IL-4 (50 ng/mL) or IL-13 (50 ng/mL, both from PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) for 4 or 24 hr then harvested and analyzed. Whole lung extracts were harvested as previously described.9 In some experiments, lung extracts were generated after performing bronchoalveolar lavage to remove airway luminal material so as to determine lung cell-associated Siglec-F ligand levels independent of airway secretions.

Western Blotting

Expression levels of Siglec-F binding proteins and Muc5b were assayed by western blotting using standard separation and transfer techniques. For detection of Siglec-F binding proteins, the blots were incubated with Siglec-F-human IgG1 Fc chimera (Siglec-F-Fc, 0.5 μg/mL, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), which was pre-complexed with ECL anti-human IgG, horseradish peroxidase-linked whole antibody (from sheep, 1:2500, GE Healthcare, UK), in blocking solution (4% bovine serum albumin in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20) at room temperature for 1 hour. Anti-Muc5b goat polyclonal antibody I-12, used 1:300 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was diluted in blocking solution. Binding of Siglec-F or antibody probes were detected by chemiluminescence using either the ECL western blotting detection system (GE Healthcare UK Ltd, England) or the SuperSignalWest Pico Chemiluminescent substrate (ThermoScientific). Siglec-F-Fc and antibody binding was quantified by scanning densitometry using NIH ImageJ software. Some samples were pretreated with sialidase (Clostridium perfringens, 1.6 mU/mL, 2 hr, 37°C, Sigma-Aldrich; or Vibrio cholera, 100 mU/mL, 1 hr, 37°C, kindly provided by Dr. Ronald Schnaar, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine) to confirm sialidase sensitivity.

Flow Cytometric Analyses for Cellular Phenotyping

Cell surface expression of Siglec-F was performed via direct immunofluorescence as described.23 Cell surface and intracellular expression levels of Siglec-F ligands were determined with or without permeabilization. Harvested mTEC single cell suspensions were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde (5 min, RT). To permeabilize, samples were incubated in PBS-S (0.1% BSA + 0.1% saponin + 1 mM Ca++Mg++/PBS) for 10 minutes at 4°C before labeling with Siglec-F-Fc or irrelevant humanized monoclonal IgG1 (omalizumab, Genentech, South San Francisco, CA) as negative control (each at 30 μg/mL for 1 hr). After washing, the samples were incubated with appropriate fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibody then analyzed by flow cytometry.

Immunocytochemistry and Histochemistry

Disaggregated mTECs were loaded into cuvettes (1 × 105 cells/slide) then centrifuged (600 rpm, 4 min, RT). After centrifugation, samples were fixed for 1 min in methanol at RT. Ligand expression was studied by incubation with Siglec-F-Fc or irrelevant humanized monoclonal IgG1 (each at 1 μg/mL, 1 hr, 37°C), then incubating with secondary biotinylated polyclonal anti-human IgG antibody. Samples were then washed and incubated with streptavidin/alkaline phosphatase linker, followed by visualization with Vector red chromogen (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). In some experiments, samples were pretreated with or without Clostridium perfringens sialidase (10 mU/mL, 24 hr, 37°C; Sigma-Aldrich). To permeabilize cells, samples were boiled in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0 followed by 10 minutes at 95°C before staining. Biotinylated Maackia amurensis (MAA) lectin (specific for α2,3-linked sialic acid) and Sambucus nigra (SNA) lectin (specific for α2,6-linked sialic acid), each at 10 mg/mL (EY Laboratories, Inc., San Mateo, CA) were also used in some experiments as previously described.14

Tissue distribution and localization of potential Siglec-F ligand was studied by histochemistry using Siglec-F-Fc (1 μg/mL, 1 hr, 37°C, R&D Systems) detected with alkaline phosphatase imaging as previously described.

Siglec affinity enrichment

Siglec-F binding proteins were isolated at the analytic scale by incubation with Siglec-F-Fc (R&D systems). Aliquots of mTEC lysate, mTEC culture media, mouse lung lysate, or BALF were split into two and incubated with or without sialidase from Vibrio cholera at 37°C for 1 hour. The samples were pre-cleared by incubation with Protein A/G agarose beads (Thermo Scientific) for 30 minutes. Following centrifugation, the supernatants were transferred to new tubes and incubated overnight at 4°C with Protein A/G agarose beads which had been precomplexed with Siglec-F-Fc. The beads were washed with TBS/0.1% TritonX-100 (pH 7.4) three times and boiled for 3 minutes in 2X SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Eluted proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE and the resulting gels were used for silver staining or western with Siglec-F-Fc or anti-Muc5b (I-12) antibody.

Proteomic analysis of Siglec-F-binding proteins

SDS-PAGE gels were silver stained, and regions of interest were excised for subsequent analysis based on the known migration of Siglec-F-Fc binding proteins detected in parallel experiments. Gel regions were cut into pieces and destained using the Pierce Silver Stain for Mass Spectrometry reagents (Thermo Scientific, IL). Following destain, gel pieces were washed sequentially with 40 mM ammonium bicarbonate and acetonitrile, followed by reduction with 10 mM dithiothreitol for 1 h at 55°C and carboxyamidomethylation with 55 mM iodoacetamide in the dark for 45 min. After reduction and alkylation, the gel pieces were sequentially washed with 40 mM ammonium bicarbonate and acetonitrile. The washed gel pieces were rehydrated in 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.2, 1 mM CaCl2 containing Sequence Grade Modified Trypsin (Promega) and incubated at 37°C for 16 h. The resulting peptides were extracted by sequential incubations with 20%, 50% and 80% acetonitrile in 5% formic acid. The washes were combined, dried, and then further purified by C18 silica MicroSpin Column (The Nest Group Inc., MA) by eluting with 50% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid. After drying, peptides were reconstituted in 20 μl mobile phase A (0.1% formic acid in water) and loaded off-line onto a nanospray tapered capillary column/emitter (360 m × 75 m × 15 m) packed with C18 resin. After loading, the column emitters were connected in-line to a gradient pump and separated using a 160 minute linear gradient of increasing mobile phase B (80% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid in water) at a flow rate of ~400 nL/min directly into the mass spectrometer.

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis was performed on an LTQ-Orbitrap Discovery mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) equipped with a nanospray ionization source. The data-dependent workflow implemented during the LC-MS/MS run included the acquisition of full Fourier transform MS (FTMS) spectra in the Orbitrap from 300-2000 m/z. Based on the FTMS spectrum, the six most intense peaks (top 6) were selected for fragmentation in the Linear Ion Trap MS (LTQ, ITMS) by collision-induced dissociation (CID) before the acquisition of the next full MS spectrum. The resulting data were searched against the mouse proteome database (Uniprot, retrieved on June, 2012) by using the SEQUEST algorithm (Proteome Discoverer 1.1, Thermo Scientific). SEQUEST parameters were set to allow 50.0 p.p.m. of precursor ion mass tolerance and 0.8 Da of fragment ion tolerance with monoisotopic masses. Tryptic peptides were allowed with up to two missed internal cleavage sites and differential modifications were allowed for carboxyamidomethylation of cysteine and oxidation of methionine. The resulting peptide data was filtered with the charge vs. Xcorr to give a stringent false discovery rate (>0.01).

Purification of mTEC mucins (mTEMucs) from culture media

Mucins were purified from mTEC media based on their ability to be recognized by Siglec-F-Fc on western blot. Pooled mTEC culture media was adjusted to pH 7.4 by the addition of 1 M Tris-HCl buffer. The crude protein solution was applied to an anion-exchange column (QSepharose resin, Sigma-Aldrich, inner diameter 3 cm × 4 cm length) and the column was washed with 0.1 M sodium chloride in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4. Following the low-salt wash, Siglec-FFc binding proteins were eluted with 2 M sodium chloride in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH7.4. Elution was monitored by subjecting aliquots of each fraction to SDS-PAGE and Siglec-F-Fc western blotting. Fractions containing Siglec-F-Fc binding at around ≈500 kDa were pooled, concentrated, and subjected to gel filtration (Sepharose CL-4B, Sigma-Aldrich, inner diameter 1.5 cm × 92 cm length). Gel-filtration was performed in 4 M guanidinium hydrochloride in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4 with a flow rate of ~12 mL/h. Gel filtration fractions exhibiting Siglec-FFc binding by western blotting were combined and concentrated using a 100 kDa cut-off membrane filter device (Millipore) to remove residual low molecular weight contaminants. The resulting preparation of purified mTEC mucins was designated “mTEMucs”.

O-linked glycan analysis

O-linked glycans were analyzed as previously described.24 Permethylation for released glycans was performed by the standard DMSO-NaOH method of Anumula and Taylor.25 After neutralizing the permethylation reaction with acetic acid, permethylated glycans were partitioned with water-dichloromethane at a ratio of 1:1. Sulfated O-glycans were quantitatively recovered from the aqueous phase, while neutral and sialylated glycans remained in the DCM phase. Sulfated glycans in the water phase were further purified by C18 column before analysis. Permethylated glycans in both phases were analyzed by nanospray ionization-mass spectrometry (NSI-MSn) on an LTQ-Orbitrap instrument (ThermoScientific). Glycan representations in figures and tables are in accordance with the guidelines generally accepted and in use by the glycomics community (see legend for Fig 1).26

Solvolysis for desulfation

mTEMucs were desulfated by solvolysis in methanolic hydrochloride as previously described.24 The conditions employed for solvolysis were validated to completely remove sulfate from standard synthetic glycans, including 3’-sulfo-Lewisa trisaccharide (Prozyme, San Leandro, CA), 6’-sulfo-LacNAc (provided by James Paulson and Corwyn Nicholat, Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA), and sulfatide (Matreya, Pleasant Gap, PA). Extent of standard desulfation was verified by NSI-MS of permethylated derivatives which also demonstrated quantitative recovery of the expected desulfation products.

Mucin binding assay

To detect binding activity of mTEMucs to eosinophils, a portion of the material was biotinylated. Purified mTEMucs (equivalent to 300 g) was dialyzed against 50 mM NaHCO3/1 mM DTT and then incubated with 40 M sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin (GBiosciences, MO) for 2 hours at room temperature in the dark. After adding 50 L of 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), the biotinylated mTEMucs were dialyzed against 50 mM NaHCO3/1 mM DTT. Successful biotinylation of the mTEMucs were confirmed by western blot with HRP-conjugated streptavidin (Jackson ImmunoResearch lab, PA) and Siglec-F-Fc, respectively. For some experiments, binding of 100 μg/mL biotinylated mTEMucs to mouse eosinophils (pretreated with or without sialidase to remove endogenous cis Siglec-F ligands, as previously reported27) was detected using PE-conjugated streptavidin.

Apoptosis assay

Peripheral blood eosinophils were obtained from IL-5 transgenic and IL-5 transgenic x Siglec-F−/− mice. After hypotonically lysing erythrocytes, immunomagnetic negative selection was performed to generate eosinophils of >96% purity by depleting mononuclear cells with a mixture of CD90.2 and CD45R coated beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) as previously described.28 After pretreatment with sialidase (Clostridium perfringens, 0.01 U/mL, 45 min, 37 °C; Sigma-Aldrich), eosinophils (106 cells/mL) were cultured in RPMI 1640, 10% FBS, 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin for 24 hr at 37°C in the presence of IL-5 (30 ng/mL, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) together with apoptosis-inducing antibodies (rat anti-mouse Siglec-F, rat anti-mouse FAS, appropriate isotype-matched non-binding controls) or 100 μg/mL purified mouse mTECMucs for 24 hr. Eosinophil apoptosis was then assessed using flow cytometry following labeling with propidium iodide (PI) and Annexin-V as described.23

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Data were evaluated using either the two-tailed Welch's t test or one-tailed t test, and p values less than 0.05 were considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Mouse tracheal epithelial cells express constitutive, cytokine-inducible and allergic inflammation-inducible ligands for Siglec-F

Previous studies have detetced mouse lung epithelial and submucosal gland ligands for Siglec-F, and have successfully used primary mTEC, cultured under air-liquid interface conditions to recapitulate, at least in part, the presence of surface ligands for Siglec-F.9-12 By immunohistochemistry, some material recognized by Siglec-F-Fc appears on the surface of intact mTEC cells, but a large pool is also detected intracellularly following permeabilization of unstimulated cells (see Online Repository Fig E2A-C), suggesting the existence of a reservoir of Siglec-F ligand ready for secretion or externalization. This sialidase-sensitive Siglec-F binding material contains predominantly, if not exclusively, α3-linked sialic acid, rather than α6-linked sialic acid based on affinity for specific plant lectins MAA versus SNA (see Online Repository Fig E2D), also consistent with previous reports of Siglec-F binding specificity.11, 14, 15

Western blotting with Siglec-F-Fc of cell lysates and culture supernatants from mTEC, as well as whole mouse lung extracts and BALF, detected several sialidase-sensitive ligands (Fig 2A), including particularly prominent recognition of material migrating at ≈200 kDa and ≈500 kDa. The largest component of this material barely moves into the gel, consistent with the known behavior of gel-forming mucin proteins upon SDS-PAGE.29 For ease of presentation, we will refer to this material as ≈500 kDa, but this label is not meant to imply a specific molecular weight. By Siglec-F-Fc western, the material migrating at ≈200 kDa was detected in tissue lysate but not in mTEC cell lysate or mTEC culture media, and only faintly in BALF. To explore the glycan dependence of Siglec-F binding to endogenous lung ligands, tissue extracts were treated with either PNGase-F, which removes N-linked glycans, or sialidase, which removes sialic acid (both N-acetylneuraminic acid, NeuAc, and N-glycolylneuraminic acid, NeuGc). As expected, sialidase treatment eliminated Siglec-F-Fc binding. PNGase-F treatment did not affect Siglec-F-Fc labeling intensity, but slightly reduced the apparent molecular weight of the ≈200 kDa band (Fig 2B), indicating that N-linked glycans on endogenous airway ligands do not contribute appreciably to Siglec-F-Fc binding and further validating previous proposals that the glycans recognized by Siglec-F are sialylated O-linked structures.12, 13 The importance of α3-sialylation for Siglec-F binding was reinforced by assessing the expression and diversity of endogenous ligands induced by ovalbumin challenge in wild-type mice and in mice heterozygous for loss of the St3gal3 gene. While the amount of Siglec-F ligand detected in extracts of whole lungs harvested from mice subjected to ovalbumin-induced allergic inflammation was greatly increased in wild-type mice, the increase was dramatically attenuated in mice lacking one copy of the St3gal3 gene (Fig 2C). Note that data in Fig 2C were generated using mouse lungs after BAL. Since BALF appears to be enriched in the ≈500 kDa material relative to the ≈200 kDa material (see Fig 2A), the reduced abundance of ≈500 kDa material seen in Fig 2C likely reflects loss of intraluminal ligand during lavage and suggests that the highest molecular weight ligands are not necessarily integral membrane proteins. Taken together, these biochemical and cytological data demonstrate that mouse lung and mTEC are useful sources for the analysis and purification of endogenous Siglec-F-binding material.

Figure 2. Detection of high molecular weight glycoprotein ligands for Siglec-F derived from mTEC, and from normal and St3gal3+/− mouse lungs with and without allergic inflammation.

Panel A. Western blotting with Siglec-F-Fc fusion protein of mouse airway and lung samples reveals at least two major binding materials (≈200 and ≈500 kDa) in mTEC lysates, mTEC culture supernatants and tissue lysates. Representative of 3 separate experiments. Panel B. Sialidase, but not PNGaseF, eliminated binding to the ≈500 kDa material, while PNGaseF treatment slightly increased the SDS-PAGE mobility of the ≈200 kDa material without altering the intensity of Siglec-F-Fc binding. Panel C. OVA sensitization and challenge of wild-type and ST3gal3+/− mice results in increased levels of sialidase-sensitive Siglec-F ligands, but the sensitization response is attenuated in the ST3gal3+/− mice. Representative of 3 separate experiments.

Proteomic, biochemical and histochemical analyses of mouse lungs and lung-derived Siglec-F binding material identify Muc5b and Muc4 as endogenous ligands

Given the robust detection of sialidase-sensitive material of ≈500 kDa in mTEC lysates and culture supernatants, and in ovalbumin sensitized and challenged mouse lung extracts and BALF (Fig 2), these samples were subjected to affinity enrichment with Siglec-F-Fc to select for endogenous ligand candidates. Each sample was incubated with or without prior sialidase treatment to assess the glycan specificity of the affinity precipitation. Material migrating in the ≈500 kDa range was subjected to in-gel tryptic digestion and subsequent liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometric analyses. High confidence assignments identified fragments of Muc5b and Muc4 in all non-sialidase treated sources (see Tables E1 and E2 in the Online Repository). The detected peptides from the ≈500 kDa range proteins mapped to the cysteine-rich domains that separate the highly glycosylated mucin repeat domains in Muc5b and to the extracellular regions of Muc4 (see Figure E3 in the Online Repository). The Muc4 mucin is encoded by a single transcript whose translation product is cleaved, leading to the formation of a non-covalently associated transmembrane spanning complex comprised of a completely extracellular β-subunit and a transmembrane α-subunit.30 Proteomic analysis of the Siglec-F binding material that migrates at ≈200 kDa following enrichment from lung lysates identified Muc4 α-subunit (see Tables E1 and E2 and Figure E3 in the Online Repository).

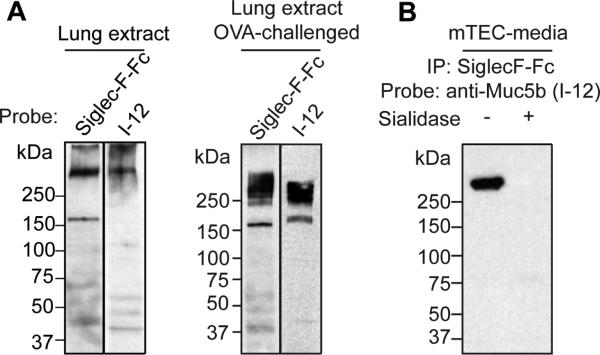

To further validate Muc5b as an endogenous Siglec-F ligand, ovalbumin sensitized and challenged mouse lung extracts were probed by western blotting with Siglec-F-Fc or anti-Muc5b antibody I-12, yielding bands of similar molecular weight in the ≈500 kDa range (Fig 3A). Furthermore, anti-Muc5b western blots of material enriched from mTEC media by Siglec-F-Fc detected a sialidase-sensitive band of ≈500 kDa (Fig 3B). Interestingly, the band from mTEC media enriched by Siglec-F-Fc, which is also recognized by western blotting with anti-Muc5b, appears to be a subset of the profile of bands directly recognized by western blotting with Siglec-F-Fc (compare Fig 3B with Fig 2A), indicating that Muc5b, by itself, does not account for all of the endogenous receptor activity, an observation that is consistent with the proteomic identification of Muc4 as another endogenous receptor. Based on its availability and simplicity compared to tissue lysates, pooled mTEC media was used as a source to generate enriched material for further biochemical and functional analyses. Through anion exchange chromatography and subsequent gel filtration under denaturing conditions, fractions enriched in Siglec-F-Fc binding activity were generated and pooled for maximum purity (see Figure E4 in the Online Repository). Proteomic analysis of the purified Siglec-F-Fc binding material demonstrated the presence of Muc5b and Muc4 (See Table E1 in the Online Repository). These purified mTEC mucin preparations (designated mTEMucs) were used for the glycomic and functional analyses described below.

Figure 3. Affinity enrichment and western blotting confirms Muc5b as a candidate ligand for Siglec-F.

Panel A. Whole lung extracts probed with Siglec-F-Fc or anti-Muc5b antibody produced similar recognition patterns for the ≈500 kDa binding material. The ≈200 kDa binding material was not recognized by anti-Muc5b antibody, consistent with proteomic analysis indicating that the ≈200 kDa binding material is derived from Muc4. Panel B. The ≈500 kDa material enriched by Siglec-F-Fc is recognized by anti-Muc5b antibody I-12.

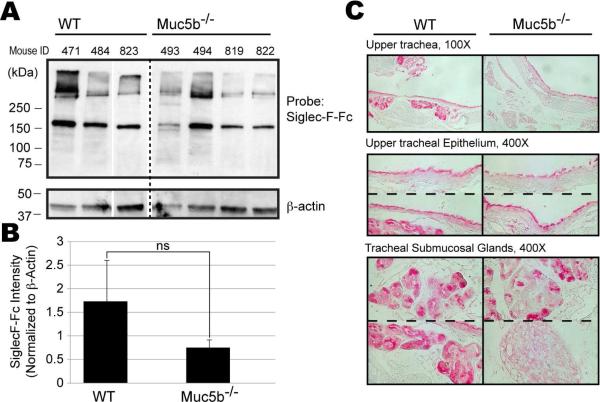

To determine if endogenous airway mucins carry glycans recognized by Siglec-F, the presence of detectable Siglec-F binding activity was assayed in mucin-deficient mouse strains. Siglec-FFc histochemistry demonstrated the presence of Siglec-F ligands in the airway epithelium and tracheal submucosal glands of Muc5ac-deficient mice and western analysis with Siglec-F-Fc also detected undiminished binding in lung lysates, excluding this mucin as a major ligand (See Figure E5 in the Online Repository). In contrast, Siglec-F-Fc western analysis of lung lysates harvested from Muc5b-deficient mice showed changes in Siglec-F-Fc binding that were variable from mouse to mouse. While two of the four Muc5b−/− mice tested showed significant decreases in Siglec-F-Fc binding, the other two were not readily distinguishable from normal when normalized to β-actin levels (Fig 4A). Quantification of Siglec-F-Fc binding by densitometry indicated a trend toward reduced binding when normalized to the actin loading control, but this difference did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 4B). Siglec-F-Fc histochemistry demonstrated an intriguing dichotomy in the same samples. Lung epithelial expression of Siglec-F ligands along ciliated surfaces was generally minimally affected, but submucosal gland expression was eliminated or reduced in all four Muc5b−/− mice (Fig 4C). Indeed, two observers blinded to the identity of these stained tissues were able to identify with 100% accuracy those that were from the wild-type versus Muc5b−/− mice. Glands have mixtures of serous and mucous cells within them, and gland ducts have mixed ciliated and non-ciliated serous/mucous cell populations. The mixed pattern of labeling is consistent with this heterogeneity, but these results also suggest that glycoproteins other than Muc5b possess Siglec-F ligands and could also present them in a compensatory fashion when Muc5b expression is lost.

Figure 4. Detection and localization of Siglec-F ligands in lung tissues of wild-type and Muc5b−/− mice.

Panel A. By western blotting, Siglec-F-Fc-binding decreased in some, but not all, Muc5b−/− mice. Data are from samples obtained at 12 months of age (sample numbers designated as 800 series) and at 12 weeks of age (sample numbers designated as 400 series) and are representative of 2 separate experiments. Panel B. Quantification of Siglec-F-Fc binding, normalized to actin, indicates a trend toward reduced binding in the Muc5b−/− mice, but the difference fails to reach statistical significance (p>0.2; ns, not significant). Panel C. Ligands are detected in tracheal epithelium and submucosal tracheal glands in wild-type mice while staining is diminished or absent in similar tissues from Muc5b−/− mice. Numbers refer to individual mice. Representative of 2 experiments in which the genotype of the samples was blinded.

To assess which proteins might be presenting Siglec-F ligands in the absence of Muc5b, we performed proteomic analysis on ≈500 kDa material enriched by Siglec-F-Fc from wild-type and from two Muc5b−/− mice, one which showed decreased Siglec-F ligand (12 week old mouse 493) and one showing robust Siglec-F ligand expression (12 week old mouse 494) by western and by histochemistry (see Table E1 in the Online Repository). Muc5b and Muc4 peptides were detected in wild-type mice, consistent with the expression of Siglec-F-recognized glycans on both mucins. Muc5b peptides were not identified in either of the Muc5b−/− mice, but Muc4 peptides were detected in mouse 494, that showed robust residual ligands by western and histochemical analysis. Muc4 peptides were not detected in Muc5b−/− mouse 493 that exhibited reduced western and histochemical Siglec-F-Fc binding. These results suggest that Muc5b and other glycoproteins such as Muc4, can present glycans recognized by Siglec-F. In the absence of Muc5b, the variability in the up-regulation of expression or glycosylation of other mucins likely reflects the unique inflammatory state of individual mice.

mTEC mucins carry sialylated and sulfated glycans

The O-linked glycans carried by Siglec-F-binding mTEMucs were released by reductive β-elimination and analyzed by NSI-MSn as their permethylated derivatives (Fig 5A). A diverse set of Core 1, Core 2, and Core 3 glycans were detected, ranging in complexity from the minimal defining core structures (Core 1, Galβ3GalNAc; Core 2, Galβ3(GlcNAcβ6)GalNAc; Core 3, GlcNAcβ3GalNAc) to branched, and extended glycans carrying between 1 and 3 LacNAc (-4Galβ4GlcNAcβ-) repeats capped with single sialic acids or with sialic acid dimers (NeuAc or NeuGc in α2-8 linkage). Sulfation was detected on the GlcNAc residue of Core 2 and Core 3 structures, consistent with the presentation of 6-sulfo-sialyl-LacNAc (6-S-Sialyl-LacNAc), not 6’-S-Sialyl-LacNAc, on mTEMucs that bind Siglec-F (Fig 5B and see Figure E6 in the Online Repository). Removal of sulfate from mTEMucs by solvolysis did not reduce Siglec-F-Fc binding but slightly altered its SDS-PAGE migration (Fig 5C), indicating that the sulfates detected as 6-sulfo-sialyl-LacNAc do not appreciably contribute to recognition.

Figure 5. mTEC mucins (mTEMucs) carry sialylated and sulfated glycans.

Panel A. A representative full MS spectrum of the O-linked glycans released from mTEMucs demonstrates the relative abundance of the various core structures. Panel B. Sulfated core 2 and core 3 glycans were detected with the sulfate linked to the GlcNAc residue, not the Gal residue of the LacNAc motif. Panel C. Removal of sulfate from mTEMucs by solvolysis did not diminish Siglec-F-Fc binding but did slightly retard the SDS-PAGE mobility of the mTEMuc preparation.

Purified mTEMuc material binds to mouse eosinophils via Siglec-F and induces their death

Given the proteomic identification of mTEMucs as Siglec-F ligands, subsequent experiments were performed to test whether this material could bind to mouse eosinophils via Siglec-F and cause any detectable biological activity. Previous studies demonstrated that 6’-S-Sialyl-Lex displayed on a polyacrylamide polymer bound Siglec-F on mouse eosinophils, but this binding was masked by interactions between Siglec-F and sialylated glycans on the same cell surface; removal of these sialylated cis ligands from the eosinophil surface revealed latent binding activity for ligands presented in trans.27 Therefore, mouse eosinophils were isolated from IL-5 transgenic mice and IL-5 transgenic x Siglec-F−/− mice and tested for Siglec-F surface expression by direct immunofluorescence and flow cytometry. As expected, eosinophils from IL-5 transgenic mice, but not from IL-5 transgenic x Siglec-F−/− mice, expressed Siglec-F on their surface, and antibody binding was unaffected by sialidase treatment of the eosinophils (Fig 6A). Next, biotinylated purified mTEMucs were tested for eosinophil binding activity in a similar manner (Fig 6B). Eosinophils from IL-5 transgenic mice bound biotinylated mTEMucs, but only after pretreating eosinophils with sialidase. Binding was completely eliminated by pretreating the eosinophils with an anti-Siglec-F blocking mAb. In contrast, binding of biotinylated mTEMucs to eosinophils from IL-5 transgenic x Siglec-F−/− mice was negligible. These data demonstrate that mTEMucs, containing both Muc5b and Muc4, are selective ligands for Siglec-F, and that sialylated cis ligands on the eosinophil surface compete for mTEMuc binding.

Figure 6. Purified mTEMucs bind to mouse eosinophils via Siglec-F and induce their death.

Panel A. Surface expression of Siglec-F was determined by direct immunofluorescence and flow cytometry using eosinophils from IL-5 transgenic mice and IL-5 transgenic x Siglec-F−/− mice. Panel B. Binding of biotinylated mTEMucs (100 μg/mL) to eosinophils from IL-5 transgenic mice and IL-5 transgenic x Siglec-F−/− mice was determined in the presence or absence of the indicated materials, as well as PE-conjugated streptavidin. Representative of three separate experiments. Panel C. Sialidase pretreated cells isolated from IL-5 transgenic mice were incubated with the indicated antibodies or mTEMucs (the latter at 100 μg/mL), then analyzed for apoptosis versus necrosis by flow cytometry. The “no treatment control viability” in the absence of any added antibodies or mTEMucs was 77 ± 2%. Data are from 4-5 separate experiments.

Anti-Siglec-F antibodies cause eosinophil death.7 To determine whether mTEMucs could also induce eosinophil death, sialidase-pretreated eosinophils from IL-5 transgenic mice were cultured with mTEMucs, as well as under other control conditions, and assayed for apoptosis and necrosis by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig 6C, anti-Siglec-F and anti-FAS mAbs, used as positive pro-apoptotic controls, caused a significant degree of cell death. Purified mTEMucs also induced a significant degree of cell death that was 50-60% as effective as the antibodies. Interestingly, when the type of cell death was examined following exposure to anti-Siglec-F, anti-FAS mAb, or mTEMuc, in each case about 80% of the dead cells were dual annexin V+/PI+ (data not shown), indicating that all three conditions induced a similar type of cell death.

Lastly, to determine whether mucin-mediated eosinophil death could regulate eosinophilic airway inflammation in vivo, lung specific Muc5b conditional knockout (Muc5b Δ/Δ) mice were treated with IL-13 (5 μg, i.t.). Leukocyte recruitment and survival were measured in BALF 48 h later. Only eosinophils increased in wild type mice (Fig 7A), while eosinophil as well as neutrophil numbers increased significantly (>4-fold) in Muc5b Δ/Δ mice compared to wild-type (Fig 7A and Fig E7A). There were also smaller but statistically significant increases after IL-13 in lymphocytes and macrophages in Muc5b Δ/Δ compared to wild-type mice (Fig E7A). Because the absence of Muc5b impairs mucociliary clearance18, some or all of these increases could have been due to an accumulation of both live and dead cells. However, Muc5b Δ/Δ mice showed a selective and significant reduction in the proportions of eosinophils that were annexin V+/PI− (Fig 7B). Although there were insufficient numbers of lymphocytes to accurately assess apoptosis, this difference in rates of BAL cell apoptosis was not seen with other BAL leukocytes (Fig E7B), including neutrophils, which do not express Siglec-F, and alveolar macrophages, which express Siglec-F abundantly but are resistant to apoptosis.31 In contrast, eosinophils, like all other BAL cell types, underwent necrotic cell death (PI+ cells) at rates that were not different between wild type and Muc5b Δ/Δ mice (compare Fig 7B to Fig E7B). Thus, the increase in BAL eosinophils in the Muc5b Δ/Δ mice was associated with a reduced rate of apoptosis that was specific and unique to this cell type and specific to the Muc5b-deficient status. These data are consistent with the concept that Muc5b mediates a significant pro-apoptotic pathway in vivo for resolving eosinophilic inflammation.

Figure 7. Lung specific conditional Muc5bΔ/Δ mice display enhances BAL eosinophilia and decreased rates of eosinophil apoptosis after intratracheal IL-13.

Total numbers of BAL eosinophils were determined (panel A), and the percentages of eosinophils that were positive or negative for PI and annexin-V labeling (panel B) were enumerated in BAL 48 hours after i.t. instillation of a single dose of 5 μg of IL-13. Data are means ± SD from a single experiment with 4-5 mice in each group.

DISCUSSION

Until now, direct identification of endogenous glycans and glycoproteins that carry relevant structures recognized by Siglec-F had not been accomplished. Proteomic, histochemical, and biochemical data together support our assignment of Muc5b as an active component in mTEMuc. Further studies are required to fully validate Muc4 in a similar manner, but both Muc5b and Muc4 were detected by affinity enrichment with Siglec-F-Fc from multiple biological sources, including lung lysates and mTEC cells. Muc5b-deficient mice exhibited decreased Siglec-F-Fc binding, most consistently in submucosal glands, but Muc4 was still detectable in Siglec-F affinity enrichments from Muc5b-deficient lungs. The variable amount of residual Siglec-F binding detected in the Muc5b-deficient mice suggests the existence of a dynamic regulatory mechanism that compensates for loss of one mucin glycan carrier by altered glycosylation or increased expression of another.

MUC5AC and MUC5B, among the five secreted human gel-forming mucins, are the only ones produced in considerable amounts in the airways.32 While MUC5B and Muc5b are the principal gel-forming mucins expressed constitutively in airways of humans and mice respectively33, 34, MUC5AC and Muc5ac are the principal gel-forming mucins upregulated in allergic airways.32, 35 Importantly, in many patients with asthma, MUC5B expression decreases by 90% or more, and this is associated with increased airway eosinophils and potentiated airway hyperreactivity.36, 37 Diseases associated with tissue eosinophilia and increased expression of MUC5B also include COPD38 and chronic rhinosinusitis39, while levels may be decreased in cystic fibrosis.36 Recent reports have identified a common promoter polymorphism in MUC5B that cause >30-fold changes in its expression. While associated with interstitial lung diseases40, its high prevalence in the population (~20% in Caucasians) suggests that it could affect pathobiology of more common diseases like asthma.

In contrast to the gel-forming soluble mucins, much of the literature on MUC4 and other membrane-bound mucins, such as MUC1 and MUC16, focuses on their role in controlling cancer cell growth and mucociliary function.41, 42 Muc4 is displayed on the surface of airway epithelial cells and on epithelial cancer cells including those derived from breast, pancreas and gastrointestinal cells43, and expression of Muc4 on airway epithelial cells is enhanced by IL-4 and IL-9.44, 45 The finding that both Muc5b and Muc4 can carry glycan ligands for Siglec-F suggests that their expression within the airway can modulate the activity of infiltrating cells that express Siglec-F. In the mouse, the cells predominantly expressing Siglec-F are eosinophils and alveolar macrophages.7 Unlike mouse eosinophils, alveolar macrophages do not appear to undergo apoptosis when Siglec-F is engaged.46 And while human eosinophils express the closest functional paralog of Siglec-F, namely Siglec-8, human alveolar macrophages do not.7 Based on these observations, we propose that constitutive and inducible mucins derived from airway epithelium and glands play a previously unappreciated role in dampening eosinophilic inflammation via siglec-sialoside interactions. This hypothesis is consistent with reports showing that other mucins bind other siglec family members. For example, tumor cell-derived mucins can bind B cells via CD22 (Siglec-2) and dendritic cells via Siglec-9 and inhibit their function.47, 48 More specifically, MUC1 glycans can bind sialoadhesin (Siglec-1), Siglec-4a and Siglec-9, and can alter cell adhesion, growth and survival.49-52 MUC2 glycans reportedly can bind to CD33 (Siglec-3) on monocytes and dendritic cells and induce apoptosis53, while glycans on MUC16 are recognized by NK cells and monocytes via Siglec-9.54, 55 In comparison to the work reported here, the glycan structures carried by these other siglec-binding mucins remain poorly characterized and none were derived from lung. While the currently and previously reported studies support an emerging theme, namely the functional importance of mucin-siglec interactions, the tissue- and cell-type specific regulation of mucin glycosylation must be considered carefully in defining functionally relevant siglec ligands.

The glycans identified by array screening as the most potent ligands for Siglec-F present certain problems considering the known specificities of the enzymes that are most likely to be responsible for their biosynthesis. Sulfation and sialylation on the terminal Gal of the LacNAc or Lex core are mutually exclusive and have not previously been detected in biological materials, including mouse lung.13, 56 In the current analysis, we were also unable to detect 6’-sulfation of sialylated glycans on our mTEMuc preparations. Furthermore, desulfation failed to eliminate binding, calling into question the importance of sulfate for Siglec-F binding in the airway. Our result is consistent with a recent report in which Siglec-F binding was detected in the lungs of knockout mice deficient for sulfotransferases known to be capable of adding sulfate to Gal residues.13 In fact, the most recent glycan array binding data for Siglec-F demonstrates that, although the 6’-S-Sialyl-Lex and 6’-S-Sialyl-LacNAc glycans are high affinity ligands, reasonable binding is also achieved to non-sulfated glycans that carry at least one sialyl-LacNAc moiety.27 The O-linked glycan diversity we have detected on mTEMuc encompasses multiple glycans with between one and three LacNAc repeats capped by sialylation, including sialic acid in α2-8 linkage to another sialic acid residue. Mucins are, by their molecular structure, capable of presenting glycans in arrays of very high valency. This presentation may enhance the binding of Siglec-F to glycans that possess lower avidity in vitro, but greater biological relevance in vivo. The library of mTEMuc glycan structures described here is an important major step towards the more technically challenging goal of identifying active glycans and assessing whether these structures are found at specific sites on mucin glycoprotein backbones.

These studies raise interesting questions relating to in vivo biology of Muc5b in mice. We used a single dose of 5 μg of intratracheal IL-13 in order to initiate a modest Th2-like inflammatory response that would allow for the detection of an augmented cellular response in the Muc5b Δ/Δ mice. The cellular pattern elicited included increases in eosinophils as expected, but also an increase in neutrophils, lymphocytes and macrophages. Muc5b-deficient mice have defects in mucociliary clearance that affect the inflammatory milieu by increasing the total amounts of cellular debris and microbial antigens that are normally eliminated by Muc5b-rich mucus, which likely explains the broader inflammatory cell influx. Also, the inflammatory patterns seen after intratracheal IL-13 do not necessarily mean that the same patterns would be seen following allergen sensitization and challenge. The simpler IL-13 model was chosen because interpreting experiments with mucin-deficient animals with airway-delivered stimuli is complicated by the fact that there is augmented retention in the lungs of this material given the reduced airways mucosal clearance seen in these mice. This could affect both the deposition and retention of allergens delivered to the airways, as well as the enhanced accumulation of inflammatory cells in the airways, and will always be a limitation associated with these models. Regardless, the increased airway eosinophilia associated with reduced rates of apoptosis observed here after IL-13 administration is consistent with the underlying hypothesis that Muc5b selectively influences eosinophil accumulation and death in the mouse airway. Previously published findings of a small but significant increase in eosinophils in the lungs of both naïve and Staphylococcus-infected Muc5b−/− mice are also consistent with this hypothesis, especially given the fact that circulating levels of eosinophils are unaffected.18

Other interesting questions arise from the detection of residual Siglec-F-Fc-binding glycoproteins in Muc5b−/− mice. The first question of interest is the identity of these additional binding proteins. Proteomic analysis clearly identified Muc4 as one binding component in Muc5b−/− mice. Although Muc4 and Muc5b were also detected as ligands in normal mouse airway samples, and although Siglec-F-Fc labeling was detected in the ciliary space of the epithelium in the Muc5b−/− mice (an expected location for transmembrane mucins), the possibility still remains that additional mucin and non-mucin glycoproteins may present Siglec-F ligands in the airway. Complete identification of all Siglec-F ligands will require additional experiments, including analyses of lung material from mice lacking Muc4 or lacking both Muc5b and Muc4. Nonetheless, the individual-to-individual variability in the level of residual binding in Muc5b−/− mice indicates that the regulatory network underlying the production of Siglec-F ligands must be flexible enough to ensure the placement of appropriate glycans on more than a single core protein. Carrier protein diversity may, in fact, facilitate the presentation of active glycans within different airway domains (glands, epithelial surfaces, ciliary spaces, etc.), providing additional opportunities for targeting immune cell responses.

The repertoire of glycans found on glycoproteins reflects poorly understood and complex interactions between many cell signaling pathways and other environmental cues. Changes in cytokine and growth factor stimulation impact the type of glycan structures presented at many cell surfaces.57, 58 Furthermore, genome-wide association studies are increasingly identifying the glycomic consequences of human genetic diversity and the novel associations between glycosylation and disease.59 Thus, the functional role of mucin glycosylation in regulating eosinophilia proposed here suggests that asthmatic severity among humans may derive, in part, from intrinsic differences in the glycan biosynthetic machinery of susceptible individuals. Developing strategies to regulate cellular glycosylation pathways or to provide exogenous effector glycans that might be missing in asthmatic individuals may provide novel and highly effective therapeutic targets.

Supplementary Material

Key messages.

This is the first report characterizing candidate endogenous lung-derived ligands for Siglec-F on mouse eosinophils.

Identified Siglec-F binding material included sialylated glycans displayed on the airway mucins Muc5b and Muc4, and confirmed that Muc5b can bind to eosinophils and induce their death in vitro.

Mice conditionally deficient in Muc5b displayed exaggerated lung eosinophilic inflammation in response to intratracheal IL-13, which was associated with reduced rates of eosinophil apoptosis.

These data support the concept that airway mucins, via their sialylated glycan ligands for Siglec-F, represent an important innate pathway for controlling lung eosinophilia.

Capsule Summary.

These studies resulted in the discovery of a previously unrecognized endogenous anti-inflammatory property of airway mucins, such as Muc5b, by which the sialylated glycans displayed on theses mucins can bind to Siglec-F, a pro-apoptotic surface protein selectively expressed on mouse eosinophils, and induce their death, thereby reducing pulmonary eosinophilia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants AI72265 (to B.S.B. and Z.Z.), HL080396, ES023384 (to C.M.E.), HL109517 (to W.J.J.), P41 GM103490 (to M.T.) and HL107151 (to B.S.B., Z.Z. and M.T.) from the National Institutes of Health, as well as American Heart Association grant 14GRNT19990040 (to C.M.E.). We thank Drs. James and Nancy Lee, Ajit Varki and Jamey Marth for providing mice used in our experiments, and Drs. James Paulson, Corwyn Nicholat and Ronald Schnaar for providing critical reagents.

Abbreviations

- 6’-S-Sialyl-LacNAc

6’-sulfo-sialyl-N-acetyl-D-lactosamine

- 6’-S-Sialyl-Lex

6’-sulfo-sialyl-Lewis X

- ALI

air-liquid interface

- BALF

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid C6ST1 chondroitin 6-O-sulfotransferase

- CID

collision-induced dissociation

- FTMS

Fourier transform mass spectrometry

- IL

interleukin

- i.t.

intratracheal

- ITMS

ion trap mass spectrometry

- KSGal6ST

keratin sulfate galactose 6-O-sulfotransferase

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

- MAA

Maackia amurensis lectin

- mTEC

mouse tracheal epithelial cells

- mTEMucs

mTEC mucins

- NSI-MSn

nanospray ionization-mass spectrometry

- OVA

ovalbumin

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PI

propidium iodide

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse transcription - polymerase chain reaction

- Siglec

sialic acid-binding, immunoglobulin-like lectin

- SNA

Sambucus nigra lectin

- ST3Gal-III

St3gal3 gene product α2,3 sialyltransferase type 3

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

Dr. Bochner is a co-inventor on existing and pending Siglec-8-related patents and may be entitled to a share of future royalties received by Johns Hopkins University on the potential sales of such products. Dr. Bochner is also a co-founder of Allakos, Inc., which makes him subject to certain restrictions under University policy. The terms of this arrangement are being managed by the Johns Hopkins University and Northwestern University in accordance with their conflict of interest policies. Dr. Bochner has current or recent consulting or scientific advisory board arrangements with Sanofi-Aventis, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, TEVA, and Allakos; and owns stock in Allakos and Glycomimetics, Inc. All other authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Barnes PJ. Immunology of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:183–92. doi: 10.1038/nri2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akdis CA. Therapies for allergic inflammation: refining strategies to induce tolerance. Nat. Med. 2012;18:736–49. doi: 10.1038/nm.2754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wenzel SE. Asthma phenotypes: the evolution from clinical to molecular approaches. Nat. Med. 2012;18:716–25. doi: 10.1038/nm.2678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bochner BS, Gleich GJ. What targeting eosinophils has taught us about their role in diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wechsler ME, Fulkerson PC, Bochner BS, Gauvreau GM, Gleich GJ, Henkel T, et al. Novel targeted therapies for eosinophilic disorders. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012;130:563–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crocker PR, Paulson JC, Varki A. Siglecs and their roles in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007;7:255–66. doi: 10.1038/nri2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiwamoto T, Kawasaki N, Paulson JC, Bochner BS. Siglec-8 as a drugable target to treat eosinophil and mast cell-associated conditions. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012;135:327–36. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Misharin AV, Morales-Nebreda L, Mutlu GM, Budinger GR, Perlman H. Flow cytometric analysis of macrophages and dendritic cell subsets in the mouse lung. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2013;49:503–10. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0086MA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiwamoto T, Brummet ME, Wu F, Motari MG, Smith DF, Schnaar RL, et al. Mice deficient in the St3gal3 gene product α2,3 sialyltransferase (ST3Gal-III) exhibit enhanced allergic eosinophilic airway inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014;133:240–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang M, Angata T, Cho JY, Miller M, Broide DH, Varki A. Defining the in vivo function of Siglec-F, a CD33-related Siglec expressed on mouse eosinophils. Blood. 2007;109:4280–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-039255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzukawa M, Miller M, Rosenthal P, Cho JY, Doherty TA, Varki A, et al. Sialyltransferase ST3Gal-III regulates Siglec-F ligand formation and eosinophilic lung inflammation in mice. J. Immunol. 2013;190:5939–48. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiwamoto T, Katoh T, Tiemeyer M, Bochner BS. The role of lung epithelial ligands for Siglec-8 and Siglec-F in eosinophilic inflammation. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013;13:106–11. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32835b594a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patnode ML, Cheng CW, Chou CC, Singer MS, Elin MS, Uchimura K, et al. Galactose 6-O-sulfotransferases are not required for the generation of Siglec-F ligands in leukocytes or lung tissue. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:26533–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.485409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo JP, Brummet ME, Myers AC, Na HJ, Rowland E, Schnaar RL, et al. Characterization of expression of glycan ligands for Siglec-F in normal mouse lungs. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2011;44:238–43. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0007OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho JY, Song DJ, Pham A, Rosenthal P, Miller M, Dayan S, et al. Chronic OVA allergen challenged Siglec-F deficient mice have increased mucus, remodeling, and epithelial Siglec-F ligands which are up-regulated by IL-4 and IL-13. Respir. Res. 2010;11:154. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee NA, McGarry MP, Larson KA, Horton MA, Kristensen AB, Lee JJ. Expression of IL-5 in thymocytes/T cells leads to the development of a massive eosinophilia, extramedullary eosinophilopoiesis, and unique histopathologies. J. Immunol. 1997;158:1332–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellies LG, Sperandio M, Underhill GH, Yousif J, Smith M, Priatel JJ, et al. Sialyltransferase specificity in selectin ligand formation. Blood. 2002;100:3618–25. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roy MG, Livraghi-Butrico A, Fletcher AA, McElwee MM, Evans SE, Boerner RM, et al. Muc5b is required for airway defence. Nature. 2014;505:412–6. doi: 10.1038/nature12807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasnain SZ, Evans CM, Roy M, Gallagher AL, Kindrachuk KN, Barron L, et al. Muc5ac: a critical component mediating the rejection of enteric nematodes. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:893–900. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng T, Zhu Z, Wang Z, Homer RJ, Ma B, Riese RJ, Jr., et al. Inducible targeting of IL-13 to the adult lung causes matrix metalloproteinase- and cathepsin-dependent emphysema. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;106:1081–93. doi: 10.1172/JCI10458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okubo T, Knoepfler PS, Eisenman RN, Hogan BL. Nmyc plays an essential role during lung development as a dosage-sensitive regulator of progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation. Development. 2005;132:1363–74. doi: 10.1242/dev.01678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.You Y, Richer EJ, Huang T, Brody SL. Growth and differentiation of mouse tracheal epithelial cells: selection of a proliferative population. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2002;283:L1315–21. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00169.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mao H, Kano G, Hudson SA, Brummet M, Zimmermann N, Zhu Z, et al. Mechanisms of Siglec-F-induced eosinophil apoptosis: a role for caspases but not for SHP-1, Src kinases, NADPH oxidase or reactive oxygen. PLoS. One. 2013;8:e68143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumagai T, Katoh T, Nix DB, Tiemeyer M, Aoki K. In-gel β-elimination and aqueous-organic partition for improved O- and sulfoglycomics. Anal. Chem. 2013;85:8692–9. doi: 10.1021/ac4015935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anumula KR, Taylor PB. A comprehensive procedure for preparation of partially methylated alditol acetates from glycoprotein carbohydrates. Anal. Biochem. 1992;203:101–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90048-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Varki A, Sharon N. Chapter 1. Historical background and overview. In: Varki A, Cummings RD, Esko JD, Freeze HH, Stanley P, Bertozzi CR, et al., editors. Essentials of Glycobiology. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor (NY): 2009. pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tateno H, Crocker PR, Paulson JC. Mouse Siglec-F and human Siglec-8 are functionally convergent paralogs that are selectively expressed on eosinophils and recognize 6′-sulfo-sialyl Lewis X as a preferred glycan ligand. Glycobiology. 2005;15:1125–35. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwi097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobsen EA, Ochkur SI, Pero RS, Taranova AG, Protheroe CA, Colbert DC, et al. Allergic pulmonary inflammation in mice is dependent on eosinophil-induced recruitment of effector T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:699–710. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thornton DJ, Rousseau K, McGuckin MA. Structure and function of the polymeric mucins in airways mucus. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2008;70:459–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chaturvedi P, Singh AP, Batra SK. Structure, evolution, and biology of the MUC4 mucin. FASEB J. 2008;22:966–81. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9673rev. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janssen WJ, Barthel L, Muldrow A, Oberley-Deegan RE, Kearns MT, Jakubzick C, et al. Fas determines differential fates of resident and recruited macrophages during resolution of acute lung injury. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011;184:547–60. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1891OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fahy JV, Dickey BF. Airway mucus function and dysfunction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:2233–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0910061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wickstrom C, Davies JR, Eriksen GV, Veerman EC, Carlstedt I. MUC5B is a major gel-forming, oligomeric mucin from human salivary gland, respiratory tract and endocervix: identification of glycoforms and C-terminal cleavage. Biochem. J. 1998;334(Pt 3):685–93. doi: 10.1042/bj3340685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seibold MA, Smith RW, Urbanek C, Groshong SD, Cosgrove GP, Brown KK, et al. The idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis honeycomb cyst contains a mucocilary pseudostratified epithelium. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Young HW, Williams OW, Chandra D, Bellinghausen LK, Perez G, Suarez A, et al. Central role of Muc5ac expression in mucous metaplasia and its regulation by conserved 5′ elements. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2007;37:273–90. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0460OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henke MO, Renner A, Huber RM, Seeds MC, Rubin BK. MUC5AC and MUC5B Mucins Are Decreased in Cystic Fibrosis Airway Secretions. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2004;31:86–91. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0345OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woodruff PG, Modrek B, Choy DF, Jia G, Abbas AR, Ellwanger A, et al. T-helper type 2-driven inflammation defines major subphenotypes of asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2009;180:388–95. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0392OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kirkham S, Kolsum U, Rousseau K, Singh D, Vestbo J, Thornton DJ. MUC5B is the major mucin in the gel phase of sputum in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2008;178:1033–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200803-391OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim DH, Chu HS, Lee JY, Hwang SJ, Lee SH, Lee HM. Up-regulation of MUC5AC and MUC5B mucin genes in chronic rhinosinusitis. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:747–52. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.6.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seibold MA, Wise AL, Speer MC, Steele MP, Brown KK, Loyd JE, et al. A common MUC5B promoter polymorphism and pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:1503–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bafna S, Kaur S, Batra SK. Membrane-bound mucins: the mechanistic basis for alterations in the growth and survival of cancer cells. Oncogene. 2010;29:2893–904. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Button B, Cai LH, Ehre C, Kesimer M, Hill DB, Sheehan JK, et al. A periciliary brush promotes the lung health by separating the mucus layer from airway epithelia. Science. 2012;337:937–41. doi: 10.1126/science.1223012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jonckheere N, Skrypek N, Frenois F, Van Seuningen I. Membrane-bound mucin modular domains: from structure to function. Biochimie. 2013;95:1077–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Damera G, Xia B, Ancha HR, Sachdev GP. IL-9 modulated MUC4 gene and glycoprotein expression in airway epithelial cells. Biosci. Rep. 2006;26:55–67. doi: 10.1007/s10540-006-9000-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Damera G, Xia B, Sachdev GP. IL-4 induced MUC4 enhancement in respiratory epithelial cells in vitro is mediated through JAK-3 selective signaling. Respir. Res. 2006;7:39. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feng YH, Mao H. Expression and preliminary functional analysis of Siglec-F on mouse macrophages. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B. 2012;13:386–94. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1100218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Toda M, Akita K, Inoue M, Taketani S, Nakada H. Down-modulation of B cell signal transduction by ligation of mucins to CD22. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;372:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Toda M, Hisano R, Yurugi H, Akita K, Maruyama K, Inoue M, et al. Ligation of tumour-produced mucins to CD22 dramatically impairs splenic marginal zone B-cells. Biochem. J. 2009;417:673–83. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nath D, Hartnell A, Happerfield L, Miles DW, Burchell J, Taylor-Papadimitriou J, et al. Macrophage-tumour cell interactions: identification of MUC1 on breast cancer cells as a potential counter-receptor for the macrophage-restricted receptor, sialoadhesin. Immunology. 1999;98:213–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00827.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Swanson BJ, McDermott KM, Singh PK, Eggers JP, Crocker PR, Hollingsworth MA. MUC1 is a counter-receptor for myelin-associated glycoprotein (Siglec-4a) and their interaction contributes to adhesion in pancreatic cancer perineural invasion. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10222–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tanida S, Akita K, Ishida A, Mori Y, Toda M, Inoue M, et al. Binding of the sialic acid binding lectin, Siglec-9, to the membrane mucin, MUC1, induces recruitment of β-catenin and subsequent cell growth. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:31842–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.471318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ohta M, Ishida A, Toda M, Akita K, Inoue M, Yamashita K, et al. Immunomodulation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells through ligation of tumor-produced mucins to Siglec-9. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;402:663–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.10.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ishida A, Ohta M, Toda M, Murata T, Usui T, Akita K, et al. Mucin-induced apoptosis of monocyte-derived dendritic cells during maturation. Proteomics. 2008;8:3342–9. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Belisle JA, Horibata S, Jennifer GA, Petrie S, Kapur A, Andre S, et al. Identification of Siglec-9 as the receptor for MUC16 on human NK cells, B cells, and monocytes. Mol. Cancer. 2010;9:118. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-118. 10.1186/476-4598-9-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tyler C, Kapur A, Felder M, Belisle JA, Trautman C, Gubbels JA, et al. The mucin MUC16 (CA125) binds to NK cells and monocytes from peripheral blood of women with healthy pregnancy and preeclampsia. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2012;68:28–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2012.01113.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hiraoka N, Petryniak B, Kawashima H, Mitoma J, Akama TO, Fukuda MN, et al. Significant decrease in α1,3-linked fucose in association with increase in 6-sulfated N-acetylglucosamine in peripheral lymph node addressin of FucT-VII-deficient mice exhibiting diminished lymphocyte homing. Glycobiology. 2007;17:277–93. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwl077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wagers AJ, Kansas GS. Potent induction of α(1,3)-fucosyltransferase VII in activated CD4+ T cells by TGF-β 1 through a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent pathway. J. Immunol. 2000;165:5011–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bax M, Garcia-Vallejo JJ, Jang-Lee J, North SJ, Gilmartin TJ, Hernandez G, et al. Dendritic cell maturation results in pronounced changes in glycan expression affecting recognition by siglecs and galectins. J. Immunol. 2007;179:8216–24. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lauc G, Huffman JE, Pucic M, Zgaga L, Adamczyk B, Muzinic A, et al. Loci associated with N-glycosylation of human immunoglobulin G show pleiotropy with autoimmune diseases and haematological cancers. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.