Abstract

PURPOSE

This study reports a phase I immunotherapy (IT) trial in 23 women with metastatic breast cancer consisting of eight infusions of anti-CD3 × anti-HER2 bispecific antibody (HER2Bi) armed anti-CD3 activated T cells (ATC) in combination with low dose interleukin 2 (IL-2) and granulocyte-macrophage-colony stimulating factor to determine safety, maximum tolerated dose (MTD), technical feasibility, T cell trafficking, immune responses, time to progression, and overall survival (OS).

EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

ATC were expanded from leukapheresis product using IL-2 and anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody and armed with HER2Bi. In 3+3 dose escalation design, groups of 3 patients received 5, 10, 20, or 40 × 109 armed ATC (aATC) per infusion.

RESULTS

There were no dose limiting toxicities and the MTD was not defined. It was technically feasible to grow 160 × 109 ATC from a single leukapheresis. aATC persisted in the blood for weeks and trafficked to tumors. Infusions of aATC induced anti-breast cancer responses and increases in immunokines. At 14.5 weeks after enrollment, 13 of 22 (59.1%) evaluable patients had stable disease and 9 of 22 (40.9%) had progressive disease. The median OS was 36.2 months for all patients, 57.4 months for HER2 3+ patients, and 27.4 months for HER2 0–2+ patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Targeting HER2 positive and negative tumors with aATC infusions induced anti-tumor responses, increases in Th1 cytokines and IL-12 serum levels that suggest that aATC infusions vaccinated patients against their own tumors. These results provide a strong rationale for conducting phase II trials.

Keywords: Bispecific antibody, activated T cells, Immunotherapy, Stage IV Breast Cancer

INTRODUCTION

In women who present with localized breast cancer, approximately 10% develop metastatic breast cancer (MBC) in 5 years. Although most patients experience objective responses to chemotherapy or hormonal therapies, progression is inevitable (1–3). Over expression of HER2/neu (HER2) in breast, ovarian, lung, gastric, head and neck and prostate cancers makes it an ideal target for anti-tumor agents (4, 5). Furthermore, recent studies suggest that the anti-HER2 reagents may be effective against HER2+ positive cancer stem like cells in tumors that are HER2 negative (6).

For patients with progressive HER2-positive MBC, HER2-targeted agents such as trastuzumab, pertuzumab, trastuzumab–maytansine, (7–10) lapatinib, neratinib and afatinib (11–13) have improved progression-free survival (PFS). However, these agents are not effective for MBC patients with HER2-negative disease. Non-toxic targeted approaches are needed for these patients.

Activated T cells (ATC) armed with anti-CD3 × anti-HER2 bispecific antibody (HER2Bi) exhibit high levels of specific cytotoxicity directed at both high and low HER2-expressing breast cancer cell lines (14). Arming ATC with HER2Bi redirects the non-MHC restricted cytotoxicity of ATC to HER2-specific targets (14). HER2Bi-armed ATC (aATC) repeatedly kill, proliferate, and release Th1 cytokines, RANTES and MIP-1α when co-cultured with HER2 negative cell lines (15). In murine studies, infusions of aATC completely prevented tumor development in co-injection assays and inhibited established HER2+ PC-3 tumors in SCID/Beige mice (16, 17).

In this study we used combination immunotherapy (IT) consisting of HER2Bi aATC infusions, interleukin 2 (IL-2), and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF). GM-CSF was empirically chosen because it is known as a potent immune adjuvant and approved for human use. Our data show that aATC infusions were safe and feasible, persist in patients’ blood and induce cytotoxic responses to breast cancer cells and elevations of serum immunokines.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical Protocol

Patients with MBC were enrolled in phase I clinical trial at Roger Williams Hospital in Providence (RWH), RI and Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute (KCI), Wayne State University (WSU), Detroit, MI between May, 2001 and August 2010. The protocol was reviewed and approved by protocol review committees, institutional Human Investigational Committees at RWH and WSU, and the Food and Drug Administration. RWH 01-351-46 and WSU 2006-130 (This trial was registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00027807) were monitored by RWMC and KCI data safety monitoring committees, respectively. All patients signed informed-consent prior to enrollment.

Production of Clinical HER2Bi

Trastuzumab (Herceptin®; Genentech, CA) was heteroconjugated to anti-CD3 (OKT3, Centocor, Ortho-Biotech, NJ) to produce HER2Bi under cGMP conditions (14).

Phase I Clinical Trial Design

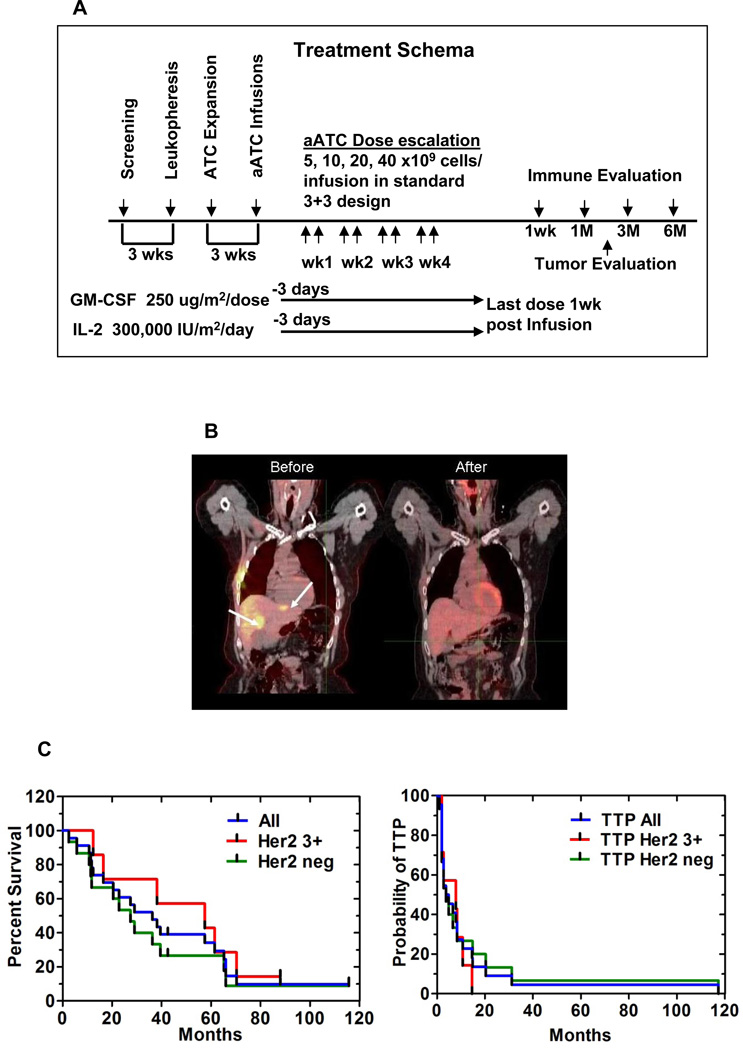

The primary endpoint was to determine the safety and maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of aATC in a standard 3 + 3 dose escalation trial with dose levels of 5, 10, 20, and 40 billion aATC per infusion (2 infusions/week for 4-weeks) for total doses of 40, 80, 160, and 320 × 109 aATC. aATC were given with IL-2 (300,000 IU/m2/day) and GM-CSF (250 µg/m2/twice weekly) beginning 3 days before the 1st infusion and ending 1 week after the last aATC infusion. Figure 1A shows the treatment schema. Tumor evaluations were performed 14.5 weeks after chemotherapy or hormonal therapy (time for lymphoid recovery, ATC production, 4.5 for weeks IT, and 4 weeks of observation). All patients with MBC (HER2 0–3+) who meet enrollment criteria were eligible.

Figure 1.

Treatment schema shows leukapheresis to obtain T cells for expansion. HER2Bi armed ATC (aATC) were administered twice weekly for four consecutive weeks. All patients received SQ IL-2 (300,000 IU/m2/day) and GM-CSF (250 µg/m2/twice weekly), beginning 3 days before the first aATC infusion and ending 1 week after the last aATC infusion. Immune testing was performed at indicated time points after aATC infusions. 1B) Shows a PET/CT of a partial responder in the HER2-negative group who had 2 well-defined liver metastases (2.5 × 1.7 cm and 2.5 × 1.3 cm as shown in Before). Reimaging after IT showed regression of the two lesions after 6 months (After). 1C) Left panel shows K-M curve for entire group (All), HER2 (3+) positive and HER2 (0–2+) negative patients. One patient with an unknown HER2 status was analyzed with the HER2 negative group. Right panel shows K-M curve for time to progression for entire group, HER2 (3+) positive and HER2 (0–2+) negative groups.

Eligibility Criteria

Women 18 years of age or older with histologically documented metastatic infiltrating ductal or lobular breast carcinoma with 0–3+ Her2 expression, Karnofsky score of ≥ 70%, ECOG 0–2, and life expectancy of > 3 months with good organ function were eligible (See supplemental information). Women with no measurable disease were eligible if the tumor or metastatic disease was removed or successfully treated before enrolment in the study. No serious medical or psychiatric illness which prevents informed consent or intensive treatment were allowed. Minor changes from these guidelines would have been allowed at the discretion of the attending team under special circumstances. The reasons for exceptions would have been documented. HER2/neu, estrogen, and progesterone receptor positivity were recorded. Details of patient characteristics are presented in Table S1.

Leukapheresis, T Cell Expansion and Production of aATC

ATC were produced as described (18). After 10–14 days, ATC were harvested and armed with 50 ng of HER2Bi/106 ATC, and cryopreserved (18). Aliquots were tested for bacteria and fungus, endotoxin, mycoplasma, phenotype, and cytotoxicity.

Dose Modification and Toxicity Scoring (NCI Toxicity Criteria, v2, June 1, 1999)

Patients were accrued to each dose level based on the dose-escalation schema (Table S2). If there was one patient with persistent grade 3 non-hematological toxicity or grade 4 toxicity was encountered in the first 3 patients or 2 out of the first six patients, the dose would not have been escalated. Patients with grade 4 non-hematologic toxicity were removed from protocol. Since cardiac toxicity associated with Herceptin® treatment was a concern (19), patients were removed if aATC infusions decreased the ejection fraction from the baseline MUGA by > 10%. Treatment was held for persistent grade 3 toxicity until toxicity decreased to < grade 2. If grade 3 toxicity occurred again, subsequent doses of aATC were washed to eliminate DMSO. If toxicity persisted, then the next dose of aATC was resumed at a 50% reduction. If the toxicities continued at the reduced dose of aATC, the IL-2 would be stopped and the aATC infusions continued at the reduced dose. If grade 3 toxicity occurred again, the ATC infusions would be stopped. Toxicities were assessed for 7 days after each infusion and weekly for unresolved toxicities.

Non-MHC Restricted Cytotoxicity

Specific cytotoxicity was performed with fresh PBMC from patients (14) using SK-BR-3 (breast specific target) and K562 cells (NK cell target) in 51Cr release assay (20). 51Cr release and IFN-γ EliSpot assays were used to assess immediate cytotoxicity of fresh endogenous PBMC directed at breast “tumor antigens” to immediately lyse tumor targets or T cells ability to secrete IFN-γ without in vitro restimulation. The cytotoxicity or IFN-γ EliSpots exhibited by PBMC would represent the development of endogenous immune responses to unknown tumor associated antigens on SK-BR-3 targets.

Cytokine Profiles

Serum cytokines were detected by multiplex cytokine array as described previously (18) using the Bio-Plex system (Bio-Rad Lab., Hercules, CA).

Immunohistochemistry

Tissues samples were sectioned, deparaffinized, stained with H&E and characterized for tumor content by a pathologist. Adjacent sections were stained with anti-CD3 to detect T cells using the Catalyzed Signal Amplification (CSA Peroxidase System, DAKO) after target retrieval and endogenous biotin/avidin and peroxidase quenching with the CSA Ancillary System (DAKO). Anti-CD3 antibody (1 µg/ml) was diluted in background reducing components (CSA Ancillary System) and incubated with tissue samples for 30 min at room temperature. Primary antibody was detected by incubating for 15 min with biotinylated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulins, and the signal was amplified and visualized by diaminobenzidine precipitation at the antigen site. In parallel, adjacent sections were stained with biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG2a followed by streptavidin-FITC to detect the goat anti-mouse-IgG2a. Images acquired using fluorescent filters were overlayed upon images acquired by light microscopy creating composite images to evaluate co-localization of staining.

Detection of aATC in Patients

Goat anti-mouse IgG2a directed at the OKT3 part of the BiAb was used to detect aATC in the peripheral blood by flow cytometry and in biopsy or surgical samples by immunohistochemistry.

Statistics

The primary endpoint of the study was to determine safety and MTD of aATC. The secondary endpoints were to assess response rates [complete response (CR), stable disease (SD), partial response (PR), and no evidence of disease (NED), time to progression (TTP), and OS. TTP and OS were measured from the date of enrollment. Kaplan-Meier estimates (K-M) were performed for OS and TTP. Descriptive statistical analyses were performed for immune monitoring using Prism (GraphPad, Version 5.0).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Table 1 and Table S1 (supplemental information) show the clinical characteristics, prior therapy, number of lines, aATC doses, sites of metastases, disease status at enrollment and at 14.5 weeks, OS for 23 women, and TTP for 22 women. Median age was 48 years (range: 31–68 years). All of the HER2 3+ patients except one (patient #16) received Herceptin (patient #16 was randomized to receive no trastuzumab on CALTB49909). All patients received chemotherapy except one (patient #8). One patient (patient #12) was treated twice but counted once for dose escalation and survival analysis. One patient had T cells expanded but was not treated due to disease progression (23 of 24 enrolled were treated).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Patient data | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| < 50 | 14 | 60.09 |

| ≥ 50 | 9 | 39.1 |

| Cancer Stage | ||

| Stage IV | 23 | 100 |

| Performance Status (ECOG) | ||

| 0 | 18 | 78.3 |

| 1 | 5 | 21.7 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 |

| ER/PR Status | ||

| Positive | 15 | 65.2 |

| Negative | 7 | 30.4 |

| Unknown | 1 | 4.3 |

| HER2/neu Status | ||

| 0 | 11 | 47.8 |

| 1+ | 2 | 8.7 |

| 2+ | 2 | 8.7 |

| 3+ | 7 | 30.4 |

| Unknown | 1 | 4.3 |

| Prior Treatment w/ Herceptin | ||

| Yes | 7 | 30.4 |

| No | 16 | 69.6 |

Phenotype and Cytotoxicity of aATC

One patient underwent a second leukapheresis to obtain the T cells necessary to meet the required dose and one patient underwent a second leukapheresis to re-grow product due to contamination or failure of aATC to mediate cytotoxicity. In the harvest product, the mean percent (± SD) viability was 91.88 ± 5.9% and the mean proportion (95% CI) of CD3, CD4, and CD8 cells were 86.7 (79.9, 93.6), 52.4 (44.6, 60.2), and 34.6% (26.9, 42.3), respectively. The ATC products were enriched for CD4+ cells; greater than 90.8% of the T cells were CD45RO+ after expansion. ATC derived from the metastatic breast cancer patients armed with Her2Bi exhibited a mean (± SD) specific cytotoxicity of 59.3% ± 11.9% (range, 12.1 – 90.7%) at an E:T of 25:1 directed at HER2+ SKBR3 targets by 51Cr release cytotoxicity assay was significantly greater (p < 0.0001) than that exhibited by patients’ unarmed ATC (3.0% ± 2.8%) before immunotherapy (Table S3). There was an inverse correlation (Spearman r = −0.5642 with a p < 0.02) between in vitro cytotoxicity of patients’ Her2Bi-ATC and proportion of CD4 cells in the expansion product. This was consistent with our report that enhanced in vitro specific cytotoxicity of armed ATC was highest in CD8+ ATC, lowest in CD4+ ATC and intermediate with unfractionated T cells.

Phase I Evaluation of MTD

The highest dose level completed was 20 × 109 aATC per infusion (160 × 109 total dose of aATC). We accrued one patient at the dose level of 40 × 109 aATC per infusion (320 × 109 total dose), but it was not technically feasible to achieve the 320 × 109 total dose with a single leukapheresis. The technically feasible dose was 160 × 109, and the MTD was not reached.

Phase I Evaluation of Toxicities

The most frequent side effect (SE) was Grade 3 chills. Grade 3 headaches emerged as the second most common SE. Table 2 shows the frequency of side effects as a function of dose level (NCI Immunotherapy Protocol Toxicity Table). By episode per infusion, the incidence of chills was 8.6, 20.8, and 43.1% at dose levels 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The incidence of headaches was 3.1, 8.3, and 19.6% at dose levels, 1, 2, and 3, respectively. All patients with grade 3 chills responded to meperidine. Patient #13 at dose level 3 experienced a grade 4 headache and hypertension and was removed from the study after 3 infusions (65.7 × 109 total aATC). The patient had developed a subdural hematoma that was evacuated without neurologic deficits or complications. Three additional patients were added to dose level 3 without any DLTs. One patient achieved dose level 4 of 40 billion/infusion dose for a total of 320 billion. One patient (#2) died of digoxin toxicity related congestive heart failure and the autopsy showed no myocardial T cell infiltrates. Patients #8 and #14 were admitted for management of hypotension, nausea, vomiting, and dehydration; there infusions were resumed and completed after resolution of their SEs. There were no DLTs attributed to aATC.

Table 2.

Toxicity Evaluation at the Dose Level 1 and 2 based on based on NCI Toxicity Criteria, v2

| Category | Adverse Reaction |

Number of Patients Affected (% at Dose Level 1) |

Total # of Episodes by Grade at Dose Level 1 |

Number of Patients Affected (% at Dose Level 2) |

Total # of Episodes by Grade at Dose Level 2 |

Number of Patients Affected (% at Dose Level 3) |

Total # of Episodes by Grade at Dose Level 3 |

Number of Patients Affected (% at Dose Level 4) |

Total # of Episodes by Grade at Dose Level 4 |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||||

| General Disorder | Chills | 5 (62.5) | 0 | 2 | 26 | 0 | 4 (66.7) | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 6 (75) | 0 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Fever | 2(25) | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 (50) | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 (25) | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Malaise | 2 (33.3) | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||||||

| Pain | 2 (33.3) | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Back Pain | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (37.5) | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | ||||||

| Weight gain | 1 (100) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| Blood Pressure | Hypotension | 1 (12.5) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 (33.3) | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 (25) | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypertension | 1 (12.5) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (25) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||||

| Cardiac | Atrial Rhythm | 1 (12.5) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||

| Tachycardia | 1 (16.7) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Gastroin-testinal | Nausea/Vomiting | 3 (37.5) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (33.3) | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 (37.5) | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 1 (16.7) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| Pulmonary | Dyspnea | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Neurological | Headache | 2 (25) | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 3 (50) | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 6 (75) | 0 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Allergy | Nasal Congestion | 1 (12.5) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||

Clinical Responses

Twenty two of 23 patients were clinically evaluable at 14.5 weeks. Patient #2 who died of digoxin toxicity was NED at time of death. Although she was not evaluable for response, she was included in the survival analysis. In the evaluable patients at 14.5 weeks, one patient had NED, one patient had a PR, 11 patients had SD, and 9 patients had PD. Patient #9 (ER+, PR- HER2-) who was progressing on letrozole developed a PR after aATC treatment that continued beyond 7 months. She had two well-defined liver metastases on a PET/CT scan (2.5 × 1.7 cm and 2.5 × 1.3 cm as shown in Figure 1B, “before”) that decreased in size after IT (Figure 1B, “after”). The sum of longest diameters was decreased by 30% at 14.5 weeks and by >70% at 7 months. At 14.5 weeks, 59.1% (13 of 22) of patients had SD or better (NED, PR, or SD) and 40.9% (9 of 22) of patients had PD. Five out of 22 (22.7%) patients with PD prior to IT achieved SD after aATC infusions.

Overall Survival and Time to Progression

Table S1 shows the disease status (most patients with visceral disease) prior to therapy, status at 14.5 weeks, TTP, and OS. Figure 1C (Left) shows the K-M curve. The median OS for 23 patients is 36.2 months, 57.4 months for the HER2 3+ group, and 27.4 months for the HER2 0–2+ group. Figure 1C (right panel) shows the K-M curve for 22 patients who were evaluable for TTP. The median TTP after enrollment was 4.2 months for the entire group, 7.9 months for the HER2 3+ group, and 3.7 months for the HER2 0–2+ group. Table S4 shows clinical responses in MBC patients who had SD at 14.5 weeks compared to patients who had PD. The median OS is 40 and 57.9 months for the HER2 0–2+ and HER2 3+ patients with SD, respectively, and 21.3 and 36.6 months for the HER2 0–2+ and HER2 3+ patients with PD, respectively. The proportion of patients (Table S5) who had SD or better was 56.5% and the proportion of patients with PD was 39.1% at 14.5 weeks (n= 23). Five of 7 (71.4%) HER2 3+ patients had SD or better disease whereas 7 of 14 (50.0%) HER2 0–2+ patients had SD or better disease. Patient #14 with an unknown HER2 status had SD (included in the HER2 0–2+ group in the K-M).

Immune Responses

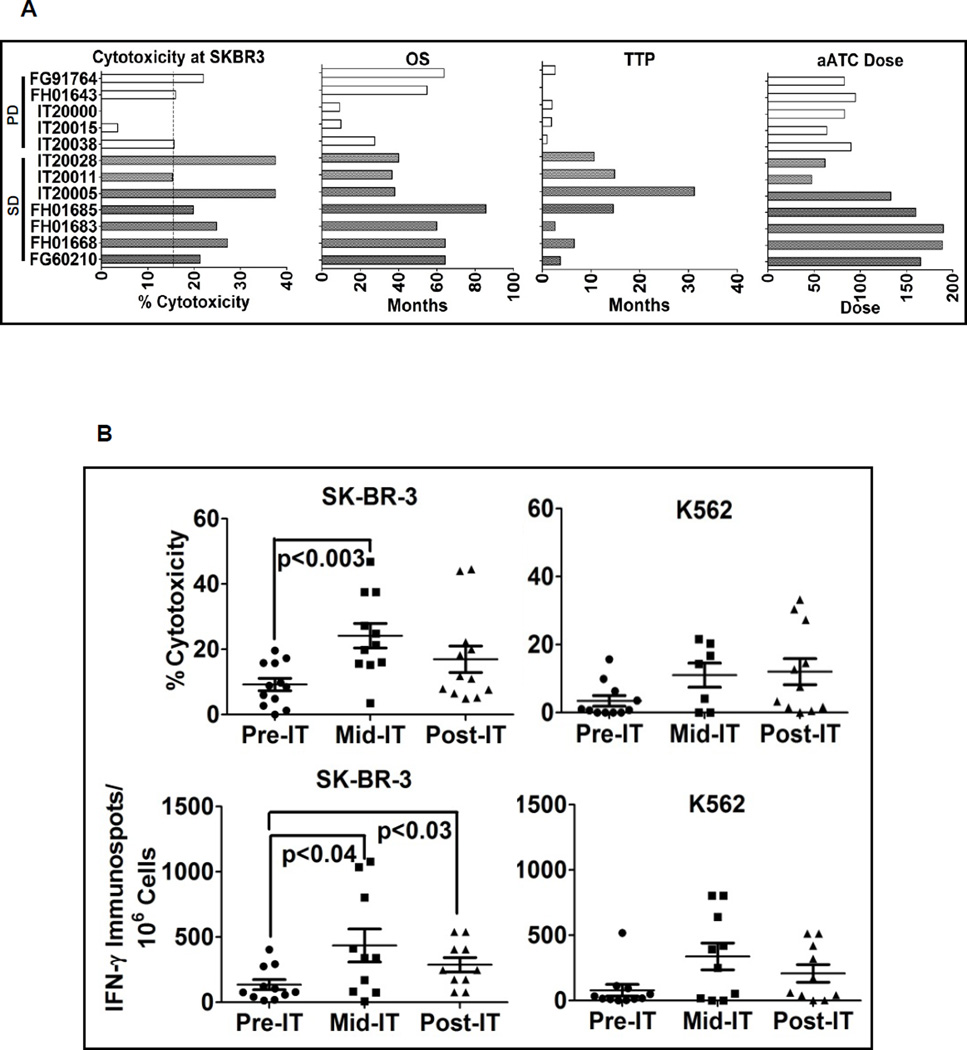

Non-MHC Restricted Cytotoxic T Cell Responses and IFN-γ EliSpots

Cytotoxicity exhibited by PBMC without stimulation directed at SK-BR-3 and K562 targets was performed to evaluate the development of immune responses by endogenous lymphocytes. Fig. 2A shows anti-SK-BR-3 cytotoxicity mediated by fresh PBMC of 12 patients along with their corresponding HER2Bi aATC dose levels, OS, and TTP. There were no correlations found between aATC dose and OS (r2 = 0.0732), aATC dose and TTP (r2 = 0.3011), cytotoxicity and OS (r2 = 0.0932), or cytotoxicity and TTP (r2 = 0.0862). Figure 2B (upper left panel) shows anti-SK-BR-3 cytotoxicity prior to immunotherapy (pre-IT), during (infusion #4 and #5) immunotherapy (mid-IT) and 4 weeks post immunotherapy (post-IT). Cytotoxicity directed at SK-BR-3 increased significantly (p < 0.003) during IT compared to pre-IT levels. The upper right panel of Figure 2B shows the increased anti-K562 (NK activity) responses at mid-IT and post-IT compared to pre-IT, but it was not significantly higher (p = 0.07) at any time point. In parallel, PBMC from selected patients were directly stimulated with SK-BR-3 for IFN-γ EliSpots. Lower left panel shows increased IFN-γ EliSpots at mid-IT (p < 0.04) and post-IT (p < 0.03) compared to the pre-IT time point. These data show that aATC infusions induced both specific anti-SK-BR-3 and innate endogenous immune responses.

Figure 2.

A) Shows the bar graph of cytotoxicity mediated by fresh PBMC of individual patients (n=12) against SK-BR-3 and their corresponding HER2Bi armed ATC doses, OS and TTP. B) Upper panel shows the enhanced cytotoxicity by PBMC directed at SK-BR-3 and K562 at pre IT, mid IT (infusion #4 or #5) and post IT (4 weeks after completion of IT). Lower panel shows T cell IFN-γ EliSpots directed at SK-BR-3 and K562 targets at pre IT, mid IT and post IT.

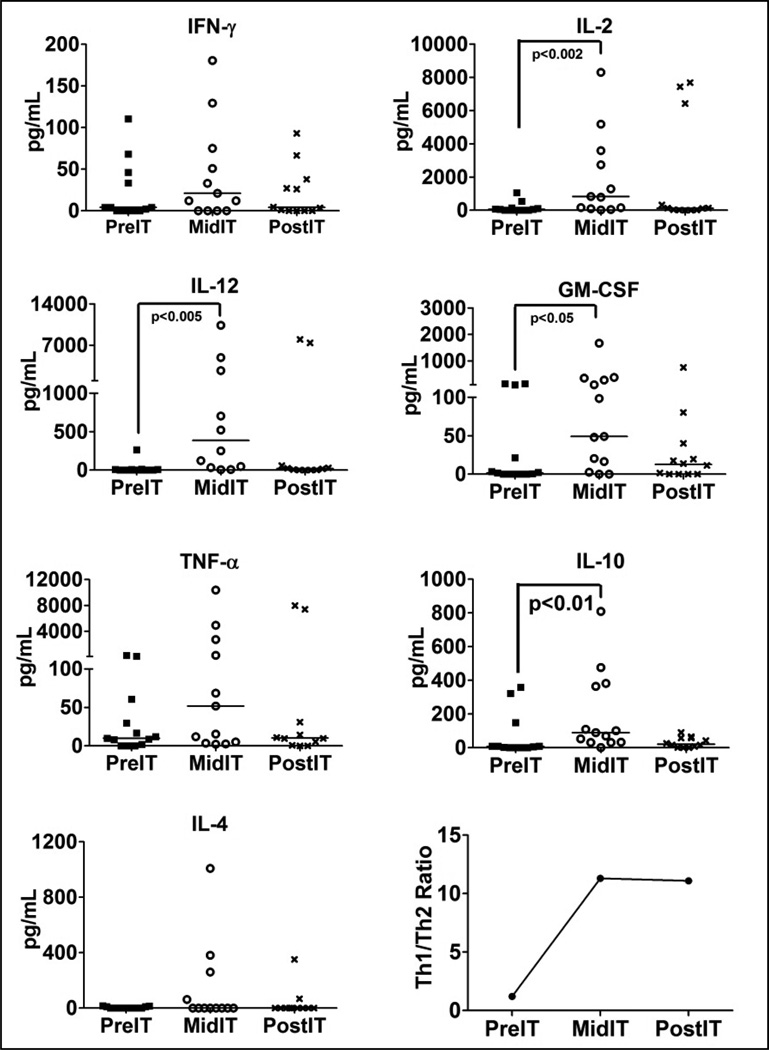

Anti-tumor Immunokines

Serum cytokine levels were tested in pre-IT serum (pre-IT), after aATC infusion #4 (mid-IT) and after completion of aATC infusions (1 week after completion of all infusions, Post-IT) to determine whether IT induced changes in serum profiles (n=13). There were significant increases in IL-12 (p < 0.0005), IL-2 (p < 0.002), GM-CSF (p < 0.05) and IL-10 (p < 0.01) levels during aATC infusions (mid-IT) compared to baseline (pre-IT). The same trend was seen for IFN-γ and TNF-α, but there were no statistical differences (Fig. 3). The lower right panel of Figure 3 shows the mean Th1/Th2 ratio = [IL-2 + IFN-γ] / [IL-4 + IL-10] at the pre-, mid- and post-IT time points.

Figure 3.

Shows profile of serum cytokines. Analysis of serum samples (n=13) at pre-immunotherapy (PreIT), after aATC infusions #4 (midIT), and post IT (4 weeks after completion of IT). Armed ATC infusions (IT) show increase in IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-12, TNF-α, GM-CSF, and IL-10 levels during aATC infusions (Mid IT). Bottom right graph shows the mean ratio of Th1/Th2=[IL-2+IFNγ]/[IL-4+IL-10] at pre-, mid- and postIT time points.

Tumor Markers

In 14 of 22 evaluable patients, 4 had a reduction in CEA (2 of 4 had a > 50% decrease and 2 of 4 had a 15 – 50% decrease), 5 had a reduction in CA 27.29 (2 of 5 had a > 50% decrease and 3 of 5 had a 15 – 50% decrease), and 5 had a reduction in soluble serum HER2 receptor (2 out of 5 had > 50% decrease and 3 of 5 had a 15 – 50% decrease) levels (Table S6).

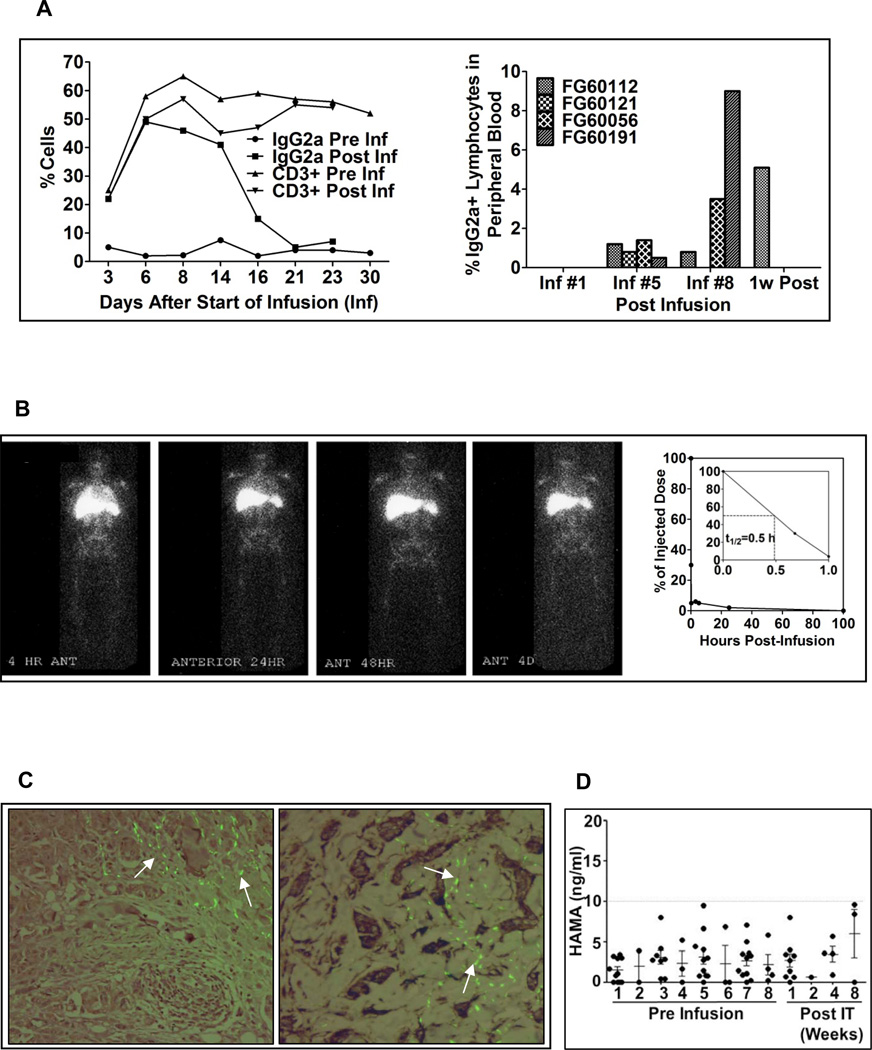

Kinetics and Survival of Infused aATC

Phenotyping of PBMC for IgG2a+ cells at pre and post infusion time points showed transient increase in IgG2a positive cells up to 50% of the circulating T cells after 2–4 hour post infusion in one patient (Figure 4A, top left panel). Phenotyping in 4 patients at post infusion #1, 5, 8 and 1 week post infusion showed accumulation and persistence of aATC up to 1 week after the last infusion in dose level 1 patients (Figure 4A, top right panel).

Figure 4.

Left panel shows the proportion of circulating CD3+ cells and IgG2a+ cells in sequential samples from 1 patient stained with anti-human CD3 and anti-mouse IgG2a+ to quantitate the proportion of HER2Bi armed ATC in the PBMC by flow cytometry. Right panel shows the proportion of circulating PBL from four patients that were stained with anti-mouse IgG2a and quantitated by flow cytometry at preinfusion #1 (Inf #1), preinfusion #5 (Inf #5), preinfusion #8 (Inf #8), and 1 week after the 8th infusion (1w post). B) Left panel shows HER2Bi-armed ATC localized to the bone marrow, lung, liver, and spleen within 4 h of injection. By 24 hours, armed ATC had cleared the lungs but persisted in the bone marrow, liver and spleen for up to 96 hours (4 days) post-infusion. Blood was sampled and counted to determine the clearance of armed ATC from the blood. Right panel shows the clearance of 111In labeled aATC. Heparinized blood (1ml aliquots) were drawn at 0, 0.7, 1, 6, 8, 27 and 96 hrs post infusion and counted for gamma irradiation. Results are presented as % radioactivity in serum (cpm) of injected dose. C) Left panel shows the sternal tumor biopsy 1 week (Left panel) and 1 month (Right panel) post IT showing poorly differentiated mammary ductal carcinoma. Composite immunofluorescent staining detected HER2Bi bispecific antibody using anti-mouse IgG-FITC overlaying IHC for detection of T cells using anti-CD3. HER2Bi detection co-localized with T cells infiltrating connective tissue surrounding nests of tumor cells. D) Shows the HAMA response before each aATC infusion and post infusions at indicated time points. HAMA antibody response (n=11) could not be detected more than 10ng/ml at any time point.

Trafficking and Clearance of aATC

Infusions of 111In labeled aATC localized to the lungs, liver, and spleen, and eventually bone marrow within 4 hours of injection in a HER2 negative patient (Figure 4B, left panel). However, the 111In labeled aATC could not be seen in the lung metastasis of a pt who was HER2 negative. After 24 hours, aATC had cleared from the lungs but persisted in the bone marrow, liver and spleen for up to 4 days post-infusion. Serial measurements of 111In labeled aATC (250 × 106) in whole blood showed that about 50% of aATC cleared from the blood within ~30 minutes but remained positive for radioactivity (1.1% of the initial concentration) up to 4 days post infusion (Figure 4B, right panel).

Localization of aATC to Tumors

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded samples were prepared from a chest wall nodule excision and a sternal tumor biopsy and stained for IgG2a on aATC. IgG2a positive aATC could be detected at 1 week (left) and 1 month (right) post treatment, respectively (Figure 4C).

Antibody responses to mouse monoclonal antibody

Patient sera were tested for human anti-mouse antibodies (HAMA) directed at murine IgG2a (OKT3). Human antibody responses to mouse IgG2a (OKT3) were very low (< 10 ng/ml) and were not clinically significant (Figure 4D).

DISCUSSION

The results from this phase I trial of HER2Bi aATC infusions in women with MBC are clinically encouraging. Multiple infusions of aATC in combination with IL-2 and GM-CSF were safe and technically feasible with persistence of the infused aATC in the circulation for 1 week. The median OS is 36.2 months for all 23 patients (22 evaluable and 1 non-evaluable = 23), 57.4 months for the HER2 3+ patients, and 27.4 months for the HER2 0–2+ patients. IT induced endogenous cytotoxic T cell and immunokine responses that persisted up to 4 months (15).

A highlight of available therapies in patients with progressive disease (regardless of HER2 status) after treatment with anthracyclines and taxanes shows OS ranging from 4 to 18.1 months (21),(22),(23),(24),(25),(26). Median OS for MBC was 18.6 months after 1st line capecitabine therapy, between 5–15 months after second line therapy, and 8 months after third line therapy (21),(22),(23),(24),(25),(26). For HER2 negative locally advanced or MBC patients, sorafenib in combination with capecitabine for first line therapy resulted in a median OS of 22.2 months (27). Second-line bevacizumab containing therapy for TNBC (RIBBON-2) showed an OS of 17.9 months (28), and combination of cetuximab with cisplatin resulted in an OS of 12.9 months (29). Use of several 3rd generation aromatase inhibitors given after tamoxifen failure as 1st or 2nd line therapy in postmenopausal women with MBC reported OS up to 26–28 months.(30)

In this phase I study, most patients were treated with ≥3 lines of therapy (14 of 23, 61%) and many had visceral disease (17 of 23, 74%) (Table S1). Infusions of aATC stabilized disease in 5 women (5 of 22, 22.7%) including a very good partial remission in patient #9. There were no DLTs observed. The major side effects were chills, fever, headache, fatigue, and hypotension. Cytokine "flurries" were observed but not life-threatening cytokine "storm". Several patients had their aATC washed to reduce side effects, but no one had their dose of aATC reduced. Three patients were hospitalized for cell-based toxicities, resolved their side effects, and completed IT without recurrent DLTs. Only patient #13 stopped therapy due to a subdural hematoma most likely due to hypertension, and patient #2 died of digoxin toxicity not related to aATC infusions. The remaining patients received their infusions as outpatients, and there have been over 115 patients to date who have received armed ATC infusions without DLTs. There were 15 patients who received anti-CD3 × anti-CD20 aATC after high dose chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation without DLTs (31, 32).

The development of CTL and IFN-γ Elispots directed at SK-BR-3 provides immunologic evidence for the development of an endogenous cellular immune response. Consistent with our previously reported data (15), these data also show persistence of CTL up to 4 months after aATC infusions. High anti-SK-BR-3 cytotoxicity levels cannot be attributed to the infused aATC since they would make up only 1% of the endogenous lymphocyte population after dilution (~1 × 1012 cells). Furthermore, our earlier aATC depletion experiment showed that endogenous cells had developed cytotoxicity directed at SK-BR-3 targets (15).

Increases in serum Th1 cytokine levels leading to high Th1/Th2 ratios and increase in IL-12 that developed mid IT and persisted for weeks after IT show that the immunologic milieu and tumor microenvironment were shifted towards an anti-tumor environment. These results are corroborated by our recent study showing that aATC targeting the triple negative cell line MDA-MB-231 in matrigel not only inhibited the growth of tumor cells but also inhibited the growth of immune suppressor cells (33) and generated a Th1 cytokine rich microenvironment. These preclinical and clinical findings support the concept of in situ vaccination with infusions of aATC.

The expansion of T cells resulted in > 90% of the T cells becoming memory phenotype of CR45RO+ with more than 50% CD4+ T cells. HER2Bi aATC showed cytotoxicity to SK-BR-3 with consistent increases in cytotoxicity as the proportion of CD8+ T cells increased in the product.

There are major differences between chimeric antibody receptors (CAR) transduced anti-CD3/anti-CD28 activated T cells (CARTs) and our approach of using the anti-CD3/IL-2 activated T cells armed with bispecific antibodies. CARTs rapidly expand and develop an anti-tumor effect upon tumor engagement. On the other hand, armed ATC mediate immediate cytotoxicity, undergo short-term proliferation, and release Th1 cytokines/chemokines in the tumor microenvironment (15). The repeated infusions of armed ATC may overcome the tumor immunosuppressive factors to recruit endogenous immune cells leading to in situ vaccination. Treating solid tumors with CAR or armed ATC approaches remains a challenge due to tumor micro-environmental factors.

In summary, aATC were not only feasible and safe but also induced endogenous cytotoxicity and cytokine responses in women with MBC with a possible survival benefit. Our findings show that cellular immune responses develop and may augment immune based killing of tumors even in patients who are progressing. These results provide the rationale for the design of phase II clinical trials using armed activated T cells in solid tumors.

Supplementary Material

STATEMENT OF TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE.

Infusions of anti-HER2 × anti-CD3 bispecific antibody (HER2Bi) armed activated T cells (aATC) are feasible, safe and did not cause dose limiting toxicities. Our phase I clinical trial using HER2Bi aATC to target HER2- and HER2+ metastatic breast cancer in combination with IL-2 and GM-CSF stabilized disease in 5 women (5 of 22 evaluable patients, 22.7%) at 14.5 weeks. Given the number of patients is small, the median OS of 36.2 months for all patients, 57.4 months for HER2 3+ patients, and 27.4 months for HER2 0–2+ patients is encouraging. aATC infusions induced significant increases in the CTL activity following immunotherapy that argues for the development of breast cancer specific endogenous immune responses. aATC infusions also polarized the immune system to a Th1/Type 1 cytokine profile with remarkable increases in IL-12 production. These results provide the rationale for the design of phase II clinical trials in solid tumors.

Acknowledgement

Special thanks to the nurse clinical coordinators: Wendy Young, Annette Olson, Lori Hall, Janet McIntyre, Patricia Steele, and Karen Myers who provided scheduling, informational, and emotional support to the women who participated in this clinical trial. The immunotherapy team acknowledges the special efforts of all of the members of the Immunotherapy Program at Roger Williams Hospital and the BMT/Immunotherapy Program at KCI that have provided support and infrastructure for the compassionate care of the women with MBC. We appreciate the careful reading and suggestions made by Drs. Abhinav Deol and Ulka Vaishampayan. The Microscopy, Imaging and Cytometry Resources Core is supported, in part, by NIH Center grant P30CA22453 to The Karmanos Cancer Institute, Wayne State University and the Perinatology Research Branch of the National Institutes of Child Health and Development, Wayne State University.

Funding Source

This study was supported by National Cancer Institute of the NIH under award numbers CA092344 (LGL), CA140314 (LGL), and P30CA022453 (Microscopy, Imaging, and Cytometry Resources Core). The studies were also supported by the Young Family Foundation and the Raymond Neag Foundation.

Footnotes

Originality Disclosure: The data presented in this manuscript is original and has not been published elsewhere except in the form of abstracts and poster presentations at symposium and meetings.

Conflict of Interest

L.G.L is co-founder of Transtarget Inc. and A.T., Z.A., F.J.C., R.D.L., D.S.D., N.K., A.M., W.C., Q.L. and R.R. have no conflicts of interest.

Contributions

L.G.L. and A.T. wrote the manuscript. L.G.L., A.T., F.J.C., R.D.L., D.S.D., N.K., A.M., W.C., Q.L., Z.A., R.R. were involved in the design, writing, regulatory, clinical management of the protocol and cell infusions. All authors were involved in the writing of the protocol. A.T. and L.G.L. were involved in producing the cGMP product, immune evaluation assays, data management, collection and analysis.

Reference List

- 1.Harris J, Morrow M, Bonadonna G. Cancer. Principles and Practice of Oncology. 4 ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muss HB, Case LD, Richards F, White DR, Cooper MR, Cruz JM, et al. Interrupted versus continuous chemotherapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer. The Piedmont Oncology Association. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1342–1348. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199111073251904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nabholtz JM, Senn HJ, Bezwoda WR, Melnychuk D, Deschenes L, Douma J, et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus mitomycin plus vinblastine in patients with metastatic breast cancer progressing despite previous anthracycline-containing chemotherapy. 304 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1413–1424. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.5.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz S, Jr, Caceres C, Morote J, de Torres I, Rodriguez-Vallejo JM, Gonzalez J, et al. Gains of the relative genomic content of erbB-1 and erbB-2 in prostate carcinoma and their association with metastasis. Int J Oncol. 1999;14:367–371. doi: 10.3892/ijo.14.2.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morote J, de Torres I, Caceres C, Vallejo C, Schwartz S, Jr, Reventos J. Prognostic value of immunohistochemical expression of the c-erbB-2 oncoprotein in metastasic prostate cancer. Int J Cancer. 1999;84:421–425. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990820)84:4<421::aid-ijc16>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korkaya H, Wicha MS. HER-2, notch, and breast cancer stem cells: targeting an axis of evil. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1845–1847. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cobleigh MA, Vogel CL, Tripathy D, Robert NJ, Scholl S, Fehrenbacher L, et al. Multinational study of the efficacy and safety of humanized anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody in women who have HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer that has progressed after chemotherapy for metastatic disease. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2639–2648. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.9.2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vogel CL, Cobleigh MA, Tripathy D, Gutheil JC, Harris LN, Fehrenbacher L, et al. Efficacy and safety of trastuzumab as a single agent in first-line treatment of HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:719–726. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.3.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gradishar WJ. HER2 therapy--an abundance of riches. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:176–178. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1113641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burris HA, III, Rugo HS, Vukelja SJ, Vogel CL, Borson RA, Limentani S, et al. Phase II study of the antibody drug conjugate trastuzumab-DM1 for the treatment of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2(HER2)-positive breast cancer after prior HER2-directed therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:398–405. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.5865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geyer CE, Forster J, Lindquist D, Chan S, Romieu CG, Pienkowski T, et al. Lapatinib plus capecitabine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2733–2743. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burstein HJ, Sun Y, Dirix LY, Jiang ZF, Paridaens R, Tan AR, et al. Neratinib, an Irreversible ErbB Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor, in Patients With Advanced ErbB2-Positive Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1301–1307. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.8707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hickish T, Wheatley D, Lin N, Carey L, Houston S, Mendelson D, et al. Use of BIBW 2992, a Novel Irreversible EGFR/HER1 and HER2 Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor To Treat Patients with HER2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer after Failure of Treatment with Trastuzumab. Cancer Res. 2009;69:785S. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sen M, Wankowski DM, Garlie NK, Siebenlist RE, Van Epps D, LeFever AV, et al. Use of anti-CD3 × anti-HER2/neu bispecific antibody for redirecting cytotoxicity of activated T cells toward HER2/neu tumors. Journal of Hematotherapy & Stem Cell Research. 2001;10:247–260. doi: 10.1089/15258160151134944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grabert RC, Cousens LP, Smith JA, Olson S, Gall J, Young WB, et al. Human T cells armed with Her2/neu bispecific antibodies divide, are cytotoxic, and secrete cytokines with repeated stimulation. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:569–576. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davol PA, Smith JA, Kouttab N, Elfenbein GJ, Lum LG. Anti-CD3 × anti-HER2 bispecific antibody effectively redirects armed T cells to inhibit tumor development and growth in hormone-refractory prostate cancer-bearing severe combined immunodeficient beige mice. Clin Prostate Cancer. 2004;3:112–121. doi: 10.3816/cgc.2004.n.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lum HE, Miller M, Davol PA, Grabert RC, Davis JB, Lum LG. Preclinical studies comparing different bispecific antibodies for redirecting T cell cytotoxicity to extracellular antigens on prostate carcinomas. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:43–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lum LG, Thakur A, Liu Q, Deol A, Al-Kadhimi Z, Ayash L, et al. CD20-targeted T cells after stem cell transplantation for high risk and refractory non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:925–933. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guarneri V, Lenihan DJ, Valero V, Durand JB, Broglio K, Hess KR, et al. Long-term cardiac tolerability of trastuzumab in metastatic breast cancer: the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4107–4115. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.9551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gall JM, Davol PA, Grabert RC, Deaver M, Lum LG. T cells armed with anti-CD3 × anti-CD20 bispecific antibody enhance killing of CD20+ malignant B-cells and bypass complement-mediated Rituximab-resistance in vitro. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:452–459. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.von MG. Evidence-based treatment of metastatic breast cancer - 2006 recommendations by the AGO Breast Commission. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:2897–2908. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaufmann M, Maass N, Costa SD, Schneeweiss A, Loibl S, Sutterlin MW, et al. First-line therapy with moderate dose capecitabine in metastatic breast cancer is safe and active: results of the MONICA trial. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:3184–3191. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vauleon E, Mesbah H, Laguerre B, Gedouin D, Lefeuvre-Plesse C, Leveque J, et al. Usefulness of chemotherapy beyond the second line for metastatic breast cancer: a therapeutic challenge. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;66:113–120. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-1141-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banerji U, Kuciejewska A, Ashley S, Walsh G, O'Brien M, Johnston S, et al. Factors determining outcome after third line chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. Breast. 2007;16:359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leonard R, O'shaughnessy J, Vukelja S, Gorbounova V, Chan-Navarro CA, Maraninchi D, et al. Detailed analysis of a randomized phase III trial: can the tolerability of capecitabine plus docetaxel be improved without compromising its survival advantage? Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1379–1385. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin M, Ruiz A, Munoz M, Balil A, Garcia-Mata J, Calvo L, et al. Gemcitabine plus vinorelbine versus vinorelbine monotherapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer previously treated with anthracyclines and taxanes: final results of the phase III Spanish Breast Cancer Research Group(GEICAM) trial. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:219–225. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baselga J, Segalla JG, Roche H, Del GA, Pinczowski H, Ciruelos EM, et al. Sorafenib in combination with capecitabine: an oral regimen for patients with HER2-negative locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1484–1491. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.7771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brufsky A, Valero V, Tiangco B, Dakhil S, Brize A, Rugo HS, et al. Second-line bevacizumab-containing therapy in patients with triple-negative breast cancer: subgroup analysis of the RIBBON-2 trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133:1067–1075. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baselga J, Gomez P, Greil R, Braga S, Climent MA, Wardley AM, et al. Randomized Phase II Study of the Anti-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Monoclonal Antibody Cetuximab With Cisplatin Versus Cisplatin Alone in Patients With Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2586–2592. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buzdar AU, Jonat W, Howell A, Jones SE, Blomqvist CP, Vogel CL, et al. Anastrozole versus megestrol acetate in the treatment of postmenopausal women with advanced breast carcinoma - Results of a survival update based on a combined analysis of data from two mature phase III trials . Cancer. 1998;83:1142–1152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lum LG, Thakur A, Liu Q, Deol A, Al-Kadhimi Z, Ayash L, et al. CD20-Targeted T Cells after Stem Cell Transplantation for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lum LG, Thakur A, Pray C, Kouttab N, Abedi M, Deol A, et al. Multiple infusions of CD20-targeted T cells and low-dose IL-2 after SCT for high-risk non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: A pilot study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013 doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thakur A, Schalk D, Sarkar SH, Al-Khadimi Z, Sarkar FH, Lum LG. A Th1 cytokine-enriched microenvironment enhances tumor killing by activated T cells armed with bispecific antibodies and inhibits the development of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1116-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lum LG, Thakur A, Rathore R, Al-Kadhimi Z, Uberti JP, Rathanatharathorn V. Phase I clinical trial involving infusions of activated T cells armed with anti-CD3 × anti-Her2neu bispecific antibody in women with metastatic breast cancer: Clinical, immune, and trafficking results. ASCO Breast Cancer Symposium; Washington, DC. Oct. 1–3, 2010.2010. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.